Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Running Head: Childhood PSTD After Natural Disaster

Hochgeladen von

api-160674927Originalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Running Head: Childhood PSTD After Natural Disaster

Hochgeladen von

api-160674927Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Running head: CHILDHOOD PSTD AFTER NATURAL DISASTER

A Review of Factors Associated with the Development of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder in Children who have experienced a Natural Disaster Jo Friesen University of Calgary

CHILDHOOD PSTD AFTER NATURAL DISASTER A Review of Factors associated with the Development of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Children who have experienced a Natural Disaster Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a potentially debilitating disorder that has a lifetime prevalence of 8% (American Psychological Association, 2000). Key diagnostic criteria include experiencing or witnessing a traumatic event, followed by symptoms related to the persistent reexperiencing of the event, avoidance of stimuli related to the event and increased arousal after the event. Unfortunately, children are not immune. Research shows that nearly two-thirds of children will experience at least one traumatic event prior to age 16 and of those, 13% will show some PTSD symptoms (Copeland, Keeler, Angold & Costello, 2007). While Copeland et al. (2007) found that less than .05% of children met the full criteria for PTSD diagnoses when experiencing their first trauma, subsequent traumas significantly increased the risk for developing PTSD. In fact, Catani, Jacob, Schauer, Kohila and Neuner (2008) found that of the children they studied, those who experience twenty-one or more past traumas, all developed PTSD. Children exposed to trauma are not only at risk for PTSD, but are also twice as likely to develop a psychological disorder than unexposed children are (Copeland et al., 2007) While the types of trauma that can trigger PTSD are vast, including witnessing violence, being the victim of abuse and severe illness or injury, the focus of this paper will be on PTSD in children following natural disasters. Natural disasters occur throughout the world, and usually without warning. They can leave death, destruction and chaos in their wake, and their effects on mental health can be similar to the consequences of war (Catani et al., 2008). Children are the most vulnerable during such an event (Demir et al., 2010), and experiencing a natural disaster has a negative effect on children in terms of their emotional and behavioural adjustment (Vijayakurmar, Kannon, Kumar, & Devarajan, 2006). PTSD symptoms may continue long after the disaster is over and symptoms include

CHILDHOOD PSTD AFTER NATURAL DISASTER nightmares, flashbacks, loss of interest, hyperarousal, regressive behaviors, somatic illnesses, school difficulties, specific fears and posttraumatic play, along with the development of anxiety and depressive disorders (Demir et al., 2010; Prinstein, La Greca, Vernberg, & Silverman, 1996). For children, the rates of PTSD after a natural disaster have been shown to be between 14-95% (Catani et al., 2008). Obviously, such a large range of prevalence rates needs to be investigated, which means that in addition to considering child risk and resiliency factors in understanding PTSD, it is important to also consider the cultural, ethnic, political and socio-economic factors that correspond to the affected region, and the severity and duration of the specific natural disaster and its aftermath. Discussion Following the 2004 Asian Tsunami, Catani et al. (2008) studied a group of children in Sri Lanka to determine what risk factors played a role in the development of PTSD. They found that a major predictor was prior trauma exposure, which in this group of children was most commonly violence within the home or war exposure (Catani et al., 2008). Other risk factors included their parents psychopathology, substance abuse (by family members), and socio-economic factors, such as unemployment, poverty and poor nutrition (Catani et al., 2008). In total, 30.4% of the children in the study met the full criteria for the disorder, with girls accounting for the largest percentage (Catani et al., 2008). In discussing their results, Catani et al. point to the importance of considering pre-disaster circumstances (in this case an ongoing war) and cultural factors (high rates of alcohol use and family violence) when assessing risk for PTSD after a natural disaster. In another study, this one conducted by Demir et al. (2010) after two earthquakes hit the Marmara region of Turkey in 1999, showed that of 321 children, 25.5% developed PTSD. Unlike Catani et al. (2008), they found no relationship between gender, but those who had lost a loved one

CHILDHOOD PSTD AFTER NATURAL DISASTER or whose homes were destroyed had the highest rates of PTSD (Demir et al., 2010). Of interest, Demir et al. found similar rates of PTSD in both the immediate quake zone and in children who were outside of the danger zone, but still felt the quake. They hypothesized that due to the high level of media coverage, the children outside the immediate danger zone who had felt the quake had assimilated the TV coverage into their own fear response (Demir et al., 2010). Like Catani et al (2008), this study demonstrated the need to consider the region and circumstances in which the disaster occurred, including what impact the infrastructure - or lack thereof may have had on PTSD rates (Demir et al., 2010). In this situation, there were high mortality rates, which were attributed in part to the social, political and economic conditions of the region (Demir et al., 2010). Following Hurricane Andrew, which hit Florida in 1992, Vernberg, La Greca, Silverman and Prinstein (1996) conducted research to test their integrative conceptual model of PTSD, which involved four primary factors: exposure to traumatic events, individual child characteristics, access to social support and childrens coping ability. Their results showed that only 14% of children expressed no PTSD symptoms, and 30% reported severe or very severe symptoms (Prinstein et al., 1996; Vernberg et al., 1996). They determined that 62% of PTSD symptoms could be accounted for by their model (Vernberg et al., 1996). They also found that exposure to traumatic events during the hurricane was the most critical factor in predicting symptoms, though they recognized that the type of exposure children experienced was itself related to other factors (such as social support and SES) (Vernberg et al., 1996). They found little evidence to support any ethnic differences (that could not be better accounted for by exposure), but as predicted, found that more girls were diagnosed than boys (Vernberg et al., 1996). Access to social support was shown to be positively correlated with the childs ability to cope effectively, and that parental support, including modeling coping behaviors, giving comfort and providing safety and security, was most

CHILDHOOD PSTD AFTER NATURAL DISASTER important (Vernberg et al., 1996). Peers offered social support and teachers were able to provide security, return to routine and information all of which also was related to decreased severity of PTSD symptoms (Vernberg et al., 1996). PTSD Factors One of the factors related to the development and severity of PTSD symptoms that came up consistently across research was exposure to trauma. Studies have looked at the effect of prior traumatic exposure (Cohen et al., 2009; Catani et al., 2008) and the level of exposure during the event (Bui et al., 2010; Cohen et al. 2009). In both situations, more exposure was related to increased symptoms and severity. While an initial exposure to trauma led to few symptoms, there was a cumulative effect of additional trauma exposures, even if they type of trauma was unrelated (Catani et al., 2008). Cohen et al. (2009) found that even though some children rated a previous event as more traumatic than the current disaster event, it was the disaster event that triggered the PTSD symptoms. In these situations, careful assessment is important, if the true source of the trauma is to be understood and treated. During the disaster, greater exposure in terms of duration and severity, and witnessing loved ones in life threatening situations were key factors in predicting PTSD symptoms. Distress during the event, including levels of fear, helplessness and horror were predictors of later PTSD symptoms as well (Bui et al., 2010). Of note with regards to trauma exposure is the relationship between such exposure and other environmental and family conditions. For instance, it may be the case that factors (such as low SES or substance abuse) that contribute to or predict family violence, are the same that contribute to increased traumatic exposure during an event. Understanding the role exposure plays in predicting PTSD in children post-disaster allows for better screening and provides insight into ways in which PTSD in such situations could be prevented or minimized.

CHILDHOOD PSTD AFTER NATURAL DISASTER A second common factor was the effect of conditions specific to the affected regions. This included political, cultural, economic and geographic factors which all impacted how the ecological system functioned before, during and after the disaster (Betancourt & Khan, 2008). In general, the predictive nature of these factors was related to how they contributed to the stability of the region, which was related to PTSD symptomology (Demir et al., 2010). Just as each natural disaster is unique, so are the circumstances in which it occurred, and often what is left in its wake is ongoing chaos, including increase criminal behaviours, disruption of social networks, separation of families, overcrowding, secondary health issues and the interruption of regular service systems (Betancourt & Khan, 2008). After Hurricane Katrina, Weems et al. (2010) found that even as long as thirty months after the disaster, PTSD symptoms in youth had not reduced, in large part due to the reality that their living environments were still in chaos, and most systems had not returned to normal. Cohen et al., (2009) found that delayed evacuation after the Tsunami, meaning more time spent enduring poor conditions, predicted increased PTSD symptoms. After the Marmara earthquakes, the high mortality rates were linked directly to poor infrastructure, and with increased mortality rates came increased exposure to trauma for the many children involved (Demir et al., 2010). A large scale disaster interrupts the entire ecological system which can have lasting effects on the development of the children involved, and the uniqueness of each ecological system makes it difficult to avoid such disruptions in the face of disaster. A third factor that was addressed in many studies was individual child characteristics. In general, there is consistent support that girls are more likely to develop PTSD after a natural disaster, perhaps in part due to their greater tendency to internalize, and in some cultures, due gender roles and expectations (Demir et al., 2010; Vernberg et al., 1996). Younger children are more at risk than adolescents. Augustyn & Groves (2005) hypothesized this was due to a younger

CHILDHOOD PSTD AFTER NATURAL DISASTER childs inability to comprehend cause and effect, which made them feel more helpless and uncertain of how they could protect themselves. There has been little evidence that ethnicity is a factor, as most of the variance in rates can be accounted for due to other factors (such as poverty, ability to evacuate, and subsequent exposure to the disaster) (Vernberg et al., 1996). Also related to individual child characteristics are resiliency factors related to PTSD, including high intelligence, religious practice, loving parenting, sense of future, internal locus of control and good coping skills (Betancourt & Khan, 2008) . Pina et al. (2008) studied Hurricane Katrina survivors and compared children with avoidant coping behaviors (blame, anger, social withdrawal) and children who used active coping behaviours (cognitive restructuring, problem focused). They found that avoidant coping style helped to predict PTSD, but interestingly, active coping did not serve as a protective factor (Pina et al., 2008). They hypothesized this may be due to the nature of the situation, and whether active coping strategies were reasonable under the circumstances (Pina et al., 2008). Vernberg et al. (1996) found a high positive correlation between high levels of distress and a greater use of all coping mechanisms, with social withdrawal having the highest correlations with PTSD symptoms. Although the value and impact of positive coping skills may not be clearly determined yet by the research, the negative impact of poor skills, such as social withdrawal are well documented. A final factor that appeared across studies was the value of social support. After Hurricane Andrew, children with strong social support were able to cope more effectively, and their access to social services was a significant predictor of PTSD symptoms severity (Vernberg et al., 1996). In the wake of Hurricane Katrina, social support from sources outside of the family (teachers, friends, church members) predicted lower levels of PTSD symptoms, as did professional support (Pina et al., 2008). One difference between these two studies is that Vernberg et al. (1996) found that

CHILDHOOD PSTD AFTER NATURAL DISASTER parental support had the greatest impact, while Pina et al. (2008) found social support outside the home made more of a difference. One reason for this difference could be the unique nature of the Katrina disaster, including the large number of families that were separated and the high levels of trauma for the entire family after the event, perhaps leaving parents with fewer resources or higher stress levels (Kelley et al., 2010). Another reason could be that while parental support is a positive factor, it factored equally for both children with and without PTSD symptoms, thereby not registering a significant effect (Pina et al., 2008). In general, the usefulness of social support depends upon the source and the type of support offered, which considering the different variables involved, lends credence to the idea that having multiple sources of support, in a variety of places (home, school, community, church) is in the best interest of the child (Vernberg et al., 1996). After the Disaster Of course, research into the factors related to the development of PSTD in children following a natural disaster is done in order to understand how best to support those children and offer them the best hope for successful outcomes. For many disorders, one area to look into is prevention. In this case, it is obvious that natural disasters cannot be prevented, but in many cases the severity of them can be mitigated. As weve seen, PTSD rates are connected the severity of exposure and the chaos experienced in the aftermath, which are factors that can be at least partially controlled through planning and infrastructure. More emphasis, however, has been placed on screening and intervention for children immediately following the disaster. Early intervention is critical, since left untreated, children with high levels of immediate symptoms are twelve times more likely to develop sustained, severe, PTSD symptoms (Kelley et al., 2010). Experts recommend screening for both pre-existing child characteristics that are known to be risk factors and for those who were known to have high trauma

CHILDHOOD PSTD AFTER NATURAL DISASTER exposure during the event (Augustyn & Groves, 2005; Chembot, Nakashima & Carlson, 2002). One instrument that has been tested for use is the Child PTSD Symptom Scale (CPSS), which is a self-report instrument designed specifically for children, that maps directly onto the DSM-IV-TR criteria (Foa, Johnson, Feeny, & Treadwell, 2001). Initial studies have shown that it is both reliable and valid after an acute stressor, and adapts to a variety of individual and group settings (Foa et al., 2001). Intervention strategies stress the value of family and school based interventions. Family interventions are important, as this is where children spend the majority of their time, and support can help with adjustment as well as foster healthy relationships within the family (Gerwirtz, Forgatch, & Wieling, 2008). Family interventions also allow for individualized care. As the parents are trained and supported, they are better able to meet their childs individual needs (Gerwirtz, Forgatch, & Wieling, 2008). School based interventions meet the need for children to return to a stable, predictable routine, and offer opportunities for structured activities such as drawing, play therapy, dance and drama, which can be useful in helping children to process information (Vijayakurmar et al., 2006). There are challenges with all of these interventions. The treatment of psychological needs is often not a part of the initial response after a disaster, and changing that protocol taps into economic and political factors. One suggestion by Chembot et al. (2002) is to pre-train school and public health personnel, who would have a reasonable expectation to remain after the disaster and to be the first-responders to screen and begin to address the needs they find. Cohen et al. (2009) agreed that schools were a good venue, but that personnel were not prepared, and due to the unpredictable nature of natural disasters, training and preparation would essentially have to be universal for an event that may never occur. Despite the funding and logistical obstacles of

CHILDHOOD PSTD AFTER NATURAL DISASTER implementing immediate psychological intervention following a disaster, the need is still present and important. Conclusion Research into posttraumatic stress disorder in children who have experienced a natural disaster is a small, but growing field of study. There are many challenges in pursuing research in this area, including access to children in the wake of such a crisis, ethical considerations of conducting research during a crisis, cultural and ethnic differences, and having appropriate infrastructure in place to support the research design (Demir et al., 2010; Pina et al., 2008). Despite these obstacles, this remains an important field of study. The long-term effects of PTSD on a child are substantial and pervasive (Weems et al., 2010). There are risks to academic development, as children struggle with concentration and memory (Augustyn & Groves, 2005). Social development is hindered by withdrawal, anti-social behaviors, increased substance abuse and lack of interest in activities (Augustyn & Groves, 2005). Physical development is hampered by sleep difficulties, headaches, chronic pain and nightmares (Augustyn & Groves, 2005). Knowing the effects, it is easy to see the need for good screening methods and timely intervention in the wake of a natural disaster, which requires a thorough understanding of the factors that contribute to the development of PTSD in children following a natural disaster.

CHILDHOOD PSTD AFTER NATURAL DISASTER References American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th edition: Text revision). Washington, DC. Augustyn, M., Groves, B. M. (2005). Training clinicians to identify the hidden victims: Children and adolescents who witness violence. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 29, 272278. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.08.023 Betancourt, T. S., & Khan, K. T. (2008). The mental health of children affected by armed conflict: Protective processes and pathways to resilience. International Review of Psychiatry, 20(3), 317-328. doi:10.1080/09540260802090363 Bui. E., Brunet, A., Allenou, C., Camassel, C., Raynaud, J.P., Claudet, I., Birmes, P. (2010). Peritraumatic reactions and posttraumatic stress symptoms in school-aged children victims of road traffic accidents. General Hospital Psychiatry, 32, 330-334. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.01.014 Catani, C., Jacob, N., Schauer, E., Kohila, M., & Neuner, F. (2008). Family violence, war and natural disasters: A study of the effect of extreme stress on children's mental health in Sri Lanka. BMC Psychiatry, 8(33). doi 10.1086/1471-244X-8-33 Chembot, C. M., Nakashima., & Carlson, J. G. (2002). Brief treatment for elementary school children with disaster-related posttraumatic stress disorder: A field study. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(1), 99-112. Cohen, J. A., Jaycox, L. H., Walker, D. W., Mannarino, A. P., Langley, A. K., & DuClos, J. L. (2009). Treating traumatized children after Hurricane Katrina: Project Fleur-de -lisTM. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 12, 55-64. doi: 10.1007/s10567-009-0039-2

CHILDHOOD PSTD AFTER NATURAL DISASTER Copeland, W. E, Keeler, G., Angold, A., Costello, J. (2007). Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress in childhood. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64, 577-584. Retrieved from www.archgenpsychiatry.com Demir, T., Demir, D. E., Alkas, L., Copur, M., Dogangun, B., & Kayaalp, L. (2010). Some clinical characteristic of children who survived the Marmara earthquakes. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 19, 125-133. doi: 10.1007/s00787-009-0048-1 Foa, E. B., Johnson, K. M., Feeny, N. C., Treadwell, K. R. H. (2001). The child PTSD symptom scale: A preliminary examination of its psychometric properties. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 30(3), 376-384. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3003_9 Gerwirtz, A., Forgatch, M., & Wieling, E. (2008). Parenting practices as potential mechanisms for child adjustment following mass trauma. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 34(2), 177192 Kelley, M. L., Self-Brown, S., Le, B., Bosson, J. V., Hernandez, B. C., & Gordon, A. T. (2010). Predicting posttraumatic stress symptoms in children following Hurricane Katrina: A prospective analysis of the effect of parental distress and parenting practices. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23(5), 582-590. doi: 10.1002/jts.20573 Pina, A. A., Villalta, I. K., Ortiz, C. D., Gottshchall, A.C., Costa, N. M., & Weems, C. F. (2008). Social support, discrimination, and coping as predictors of posttraumatic stress reactions in youth survivors of Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 37(3), 564-574. doi: 10.1080/15374410802148228 Prinstein, M. J., La Greca, A. M., Vernberg, E. M., & Silverman, W. K. (1996). Children's coping assistance: How parents, teachers, and friends help children cope after a natural disaster. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 25(4), 463-475.

CHILDHOOD PSTD AFTER NATURAL DISASTER Weems, C. F., Taylor, L. K., Cannon, M. F, Marino, R. C, Roman, D. M, Scott, B. G., Triplett, V. (2010). Post traumatic stress, context, and the lingering effects of the Hurricane Katrina disaster among ethnic minority youth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38I, 49-56. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9352-y Vernberg, E. M., La Greca, A. M., Silverman, W. K., Prinstein, M. J. (1996). Prediction of posttraumatic stress symptoms in children after Hurricane Andrew. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 105(2), 237-248. Vijayakurmar, L., Kannon, G. K., Kumar, B. G., & Devarajan, P. (2006). Do all children need intervention after exposure to tsunami? International Review of Psychiatry, 18(6), 515-522. doi:10.1080/09540260601039876

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Effects of Trauma in Early ChildhoodDokument10 SeitenEffects of Trauma in Early Childhoodapi-437448372100% (1)

- Hand Reflexology-Key To Perfect HealthDokument340 SeitenHand Reflexology-Key To Perfect Healthpadoita01100% (1)

- A Developmental Approach To Complex PTSD Childhood and Adult Cumulative Trauma As Predictors of Symptom Complexity.Dokument10 SeitenA Developmental Approach To Complex PTSD Childhood and Adult Cumulative Trauma As Predictors of Symptom Complexity.macrabbit8100% (1)

- Trauma, Posttraumatic Stress, and Family SystemsDokument30 SeitenTrauma, Posttraumatic Stress, and Family SystemsLIDIA KARINA MACIAS ESPARZANoch keine Bewertungen

- Trauma Focused CBT For Complex TraumaDokument16 SeitenTrauma Focused CBT For Complex TraumaTania SantamaríaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Behind Closed Doors Interpersonal Trauma PDFDokument22 SeitenBehind Closed Doors Interpersonal Trauma PDFMaría Regina Castro CataldiNoch keine Bewertungen

- PTSD AssessmentDokument28 SeitenPTSD AssessmentOdalis VelezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complex Post Traumatic StatesDokument12 SeitenComplex Post Traumatic Statesadamiam100% (3)

- Developmental Approach To Complex PTSD SX Complexity Cloitre Et AlDokument11 SeitenDevelopmental Approach To Complex PTSD SX Complexity Cloitre Et Alsaraenash1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder - An Under-Diagnosed and Under-Treated Entity PDFDokument11 SeitenPost-Traumatic Stress Disorder - An Under-Diagnosed and Under-Treated Entity PDFnegriRDNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consequences of Traumatic Stress - Diac SabinaDokument6 SeitenConsequences of Traumatic Stress - Diac SabinaSabina DiacNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding Interpersonal Trauma in Children PDFDokument14 SeitenUnderstanding Interpersonal Trauma in Children PDFjoaomartinelliNoch keine Bewertungen

- DUTIES AND FUNCTIONS OF EVERY DEPARTMENT in LguDokument3 SeitenDUTIES AND FUNCTIONS OF EVERY DEPARTMENT in LguLgu San Juan Abra100% (3)

- Child - Death of A ParentDokument6 SeitenChild - Death of A Parentjmandernach232Noch keine Bewertungen

- Principles of Adult Learning DocumentDokument41 SeitenPrinciples of Adult Learning Documentحشيمة الروحNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter10 Trasgenerational TransferDokument10 SeitenChapter10 Trasgenerational Transfernorociel8132Noch keine Bewertungen

- Jsa Welding & Gas CuttingDokument3 SeitenJsa Welding & Gas CuttingM M PRADHANNoch keine Bewertungen

- General Medical Products 1082Dokument89 SeitenGeneral Medical Products 1082Dipak Madhukar KambleNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Phenomenological Study of the Lost Generation of SudanVon EverandThe Phenomenological Study of the Lost Generation of SudanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Measuring Basic Observations: OSCE ChecklistDokument2 SeitenMeasuring Basic Observations: OSCE Checklistahmad50% (4)

- Paul 2015Dokument9 SeitenPaul 2015JoecoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arditti 2012Dokument39 SeitenArditti 2012rahafNoch keine Bewertungen

- HandbookTreatment of PTSDDokument44 SeitenHandbookTreatment of PTSDOdalis VelezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effects Psychological Trauma Children Autism - 0Dokument13 SeitenEffects Psychological Trauma Children Autism - 0H.JulcsiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Potentially Traumatic Events As Predictors of VicaDokument9 SeitenPotentially Traumatic Events As Predictors of VicaLychee YumberryNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5) Violent CrimeDokument13 Seiten5) Violent CrimeUmar RachmatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Family Functioning and Children 'S Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms in A Referred Sample Exposed To Interparental ViolenceDokument10 SeitenFamily Functioning and Children 'S Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms in A Referred Sample Exposed To Interparental ViolenceNicoll Pamela Nureña CunayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Family Context of Mental Health Risk in Tsunami-Exposed AdolescentsDokument11 SeitenFamily Context of Mental Health Risk in Tsunami-Exposed AdolescentsVirgílio BaltasarNoch keine Bewertungen

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDokument17 SeitenNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptjlventiganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Freyd 2005Dokument22 SeitenFreyd 2005Alex Alves de SouzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Traumatic Loss in Children and AdolescentsDokument13 SeitenTraumatic Loss in Children and AdolescentsGlenn ArmartyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lu, W, 2013Dokument8 SeitenLu, W, 2013Zeynep ÖzmeydanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Meta AnalysisDokument66 SeitenMeta AnalysisTarraNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2017 Dorsey JCCAP Evidence Based Update For Psychosocial Treatments For Children Adol Traumatic EventsDokument43 Seiten2017 Dorsey JCCAP Evidence Based Update For Psychosocial Treatments For Children Adol Traumatic EventsNoelia González CousidoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Psychology Discussion 4+5Dokument5 SeitenPsychology Discussion 4+5Susan SuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pre-Attack Stress-Load, Appraisals, and Coping in Children's Responses To The 9/11 Terrorist AttacksDokument10 SeitenPre-Attack Stress-Load, Appraisals, and Coping in Children's Responses To The 9/11 Terrorist AttacksTiciana Paiva de VasconcelosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cristofaro 2013Dokument8 SeitenCristofaro 2013Stella ÁgostonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Factors Associated With Traumatic Symptoms Among AdolescentsDokument13 SeitenFactors Associated With Traumatic Symptoms Among Adolescentsezuan wanNoch keine Bewertungen

- When Nowhere Is Safe: Interpersonal Trauma and Attachment Adversity As Antecedents of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Developmental Trauma DisorderDokument12 SeitenWhen Nowhere Is Safe: Interpersonal Trauma and Attachment Adversity As Antecedents of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Developmental Trauma DisorderNerea F GNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bullying and PTSD SymptomsDokument11 SeitenBullying and PTSD SymptomsAmalia PagratiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Secondary Traumatic Stress Prevalence and Symptomology PDFDokument11 SeitenSecondary Traumatic Stress Prevalence and Symptomology PDFBassam AlqadasiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lafauci, 2011Dokument8 SeitenLafauci, 2011Jbl2328Noch keine Bewertungen

- Putnam 2006Dokument11 SeitenPutnam 2006NilamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Psychometrics of The PTSD and Depression Screener For Bereaved YouthDokument13 SeitenPsychometrics of The PTSD and Depression Screener For Bereaved YouthAmanda PetinatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Flores - Post Traumatic Stress Disorder From 2007 Eq Pisco - 2014Dokument9 SeitenFlores - Post Traumatic Stress Disorder From 2007 Eq Pisco - 2014Nataly SusanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Faking It: Incentives and Malingered PTSD: Kristine A. Peace and Victoria E.S. RichardsDokument15 SeitenFaking It: Incentives and Malingered PTSD: Kristine A. Peace and Victoria E.S. Richardsangie galvisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Torres, A.S Ms Rle BibliographyDokument46 SeitenTorres, A.S Ms Rle BibliographyAndrea TorresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Secondary Traumatic Stress in School PersonnelDokument14 SeitenSecondary Traumatic Stress in School PersonnelRaluca AlexandraNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S002239562200615X MainDokument8 Seiten1 s2.0 S002239562200615X MainMalena Ureña CasamitjanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Author's Accepted Manuscript: Journal of Affective DisordersDokument41 SeitenAuthor's Accepted Manuscript: Journal of Affective DisordersRoxana MălinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Neurobiology of ResilienceDokument48 SeitenNeurobiology of ResilienceIzzyinOzzieNoch keine Bewertungen

- J. Pediatr. Psychol.-2002-Manne-607-17 PDFDokument12 SeitenJ. Pediatr. Psychol.-2002-Manne-607-17 PDFMariana ManginNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nihms 221546Dokument14 SeitenNihms 221546valentina.starkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fowler Et Al. (2013) - Exposure To Interpersonal Trauma, Attachment Insecurity, and Depression SeverityDokument6 SeitenFowler Et Al. (2013) - Exposure To Interpersonal Trauma, Attachment Insecurity, and Depression Severitylixal5910Noch keine Bewertungen

- Health Psychology: Major Flood Related Strains and Pregnancy OutcomesDokument17 SeitenHealth Psychology: Major Flood Related Strains and Pregnancy Outcomesfahrul ishakNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complex Trauma: Domestic ViolenceDokument15 SeitenComplex Trauma: Domestic ViolencemarkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wahida Nikmah - 3B - Final Exam WritingDokument6 SeitenWahida Nikmah - 3B - Final Exam WritingUlfeeya OfficialNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intensity of Event, Resilience and Education As Factors in Posttraumatic Stress Symptomatology Among Flood VictimsDokument8 SeitenIntensity of Event, Resilience and Education As Factors in Posttraumatic Stress Symptomatology Among Flood VictimsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complex Trauma Exposure and Symptoms in Urban Traumatized Children - A Preliminary Test of Proposed Criteria For Developmental Trauma DisorderDokument9 SeitenComplex Trauma Exposure and Symptoms in Urban Traumatized Children - A Preliminary Test of Proposed Criteria For Developmental Trauma DisorderCesia Constanza Leiva GonzalezNoch keine Bewertungen

- StressDokument14 SeitenStressbaconhaterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intimate Partner ViolenceDokument5 SeitenIntimate Partner ViolenceAncuţa ElenaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wardetal 2021Dokument13 SeitenWardetal 2021Katherina AdisaputroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coping With Genetic Risk - Living With HDDokument19 SeitenCoping With Genetic Risk - Living With HDYésicaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Poster # T-195 (Clin Res, Assess DX) Atlanta Ballroom Poster # T-198 (Soc Ethic, Child) Atlanta BallroomDokument2 SeitenPoster # T-195 (Clin Res, Assess DX) Atlanta Ballroom Poster # T-198 (Soc Ethic, Child) Atlanta BallroomretNoch keine Bewertungen

- Allocation of Attention To Scenes of Peer Harassment Visualcognitive Moderators of The Link Between Peer Victimization and AggressionDokument16 SeitenAllocation of Attention To Scenes of Peer Harassment Visualcognitive Moderators of The Link Between Peer Victimization and AggressionTinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- PTSD and Aother ThingsDokument15 SeitenPTSD and Aother ThingsMarkusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Client Name: Well, Max Birthdate: AGE: 7 Years, 8 Months School: Grade: 1 Dates of Assessment: July, 2011 Date of Report: Assessed By: FlamesDokument10 SeitenClient Name: Well, Max Birthdate: AGE: 7 Years, 8 Months School: Grade: 1 Dates of Assessment: July, 2011 Date of Report: Assessed By: Flamesapi-160674927Noch keine Bewertungen

- 658 Intervention Plan AssignmentDokument33 Seiten658 Intervention Plan Assignmentapi-162851533100% (1)

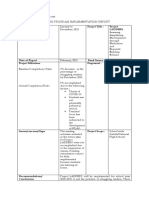

- Policy Implementation ChecklistDokument4 SeitenPolicy Implementation Checklistapi-160674927100% (1)

- Friesen Position PaperDokument27 SeitenFriesen Position Paperapi-160674927Noch keine Bewertungen

- Friesen Integrative Paper3Dokument18 SeitenFriesen Integrative Paper3api-160674927Noch keine Bewertungen

- Friesen Article ReviewDokument8 SeitenFriesen Article Reviewapi-160674927Noch keine Bewertungen

- Running Head: Working Memory Disorder InterventionsDokument14 SeitenRunning Head: Working Memory Disorder Interventionsapi-160674927Noch keine Bewertungen

- Friesen Caap 601 ComparisonDokument18 SeitenFriesen Caap 601 Comparisonapi-160674927Noch keine Bewertungen

- Caap601 - Rebt Proposed Treatment Plan 2Dokument4 SeitenCaap601 - Rebt Proposed Treatment Plan 2api-160674927100% (2)

- Upnljun 11Dokument4 SeitenUpnljun 11api-160674927Noch keine Bewertungen

- Scott CleanDokument10 SeitenScott Cleanapi-160674927Noch keine Bewertungen

- Acad - Summer Practicum Eval Form - Jo 3Dokument4 SeitenAcad - Summer Practicum Eval Form - Jo 3api-160674927Noch keine Bewertungen

- 658 Anxiety HandoutDokument2 Seiten658 Anxiety Handoutapi-162851533Noch keine Bewertungen

- Jfriesen - JarDokument4 SeitenJfriesen - Jarapi-160674927Noch keine Bewertungen

- Jfriesen Case Study 2Dokument16 SeitenJfriesen Case Study 2api-160674927Noch keine Bewertungen

- Running Head: JFRIESEN - ASSIGNMENT #1Dokument16 SeitenRunning Head: JFRIESEN - ASSIGNMENT #1api-160674927Noch keine Bewertungen

- Jfriesen Research ProposalDokument14 SeitenJfriesen Research Proposalapi-160674927Noch keine Bewertungen

- Running Head: Neuropsychological Features of Fas-DDokument13 SeitenRunning Head: Neuropsychological Features of Fas-Dapi-160674927Noch keine Bewertungen

- Running Head: Ethical Policy-Making ExerciseDokument12 SeitenRunning Head: Ethical Policy-Making Exerciseapi-160674927Noch keine Bewertungen

- Record KeepingDokument32 SeitenRecord Keepingapi-206142283Noch keine Bewertungen

- Running Head: Ethical Decision-Making ExerciseDokument12 SeitenRunning Head: Ethical Decision-Making Exerciseapi-160674927Noch keine Bewertungen

- Table of ContentsDokument2 SeitenTable of Contentsapi-160674927Noch keine Bewertungen

- Jfriesen 3Dokument14 SeitenJfriesen 3api-160674927Noch keine Bewertungen

- Running Head: Using Miscue Analysis To Detect RD in EllDokument13 SeitenRunning Head: Using Miscue Analysis To Detect RD in Ellapi-160674927Noch keine Bewertungen

- Advanced Programs For International DentistsDokument6 SeitenAdvanced Programs For International DentistsYashaswiniTateneniNoch keine Bewertungen

- OphthalmologyDokument10 SeitenOphthalmologyTadele WondimuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Child MarriageDokument3 SeitenChild MarriagevishuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 4 Managing Stress and Coping With LossDokument4 SeitenChapter 4 Managing Stress and Coping With LossVraj PatelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Methods of Plant PropagationDokument56 SeitenMethods of Plant PropagationMaryhester De leonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Edition 4.0: Please Input The Below Numbers : Subject-Wise Study Time CalculatorDokument2 SeitenEdition 4.0: Please Input The Below Numbers : Subject-Wise Study Time Calculatorsuraj kantNoch keine Bewertungen

- 30 The Social Psychology of WorkDokument18 Seiten30 The Social Psychology of WorkBryan Augusto Zambrano PomaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1) Health and Safety Interaction Form TemplateDokument1 Seite1) Health and Safety Interaction Form TemplateIgaDan100% (1)

- Complete Care For Your Family: HealthDokument19 SeitenComplete Care For Your Family: HealthNelly HNoch keine Bewertungen

- RAD 104 Chapter - 005 Introduction To Clinical Environment 2022Dokument42 SeitenRAD 104 Chapter - 005 Introduction To Clinical Environment 2022rehab ebraheemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reading Program Terminal Report-2020Dokument2 SeitenReading Program Terminal Report-2020roselyn galinatoNoch keine Bewertungen

- EWMA Endorsements of Wound Centres Non Hospital Based ApplicationForm WordDokument17 SeitenEWMA Endorsements of Wound Centres Non Hospital Based ApplicationForm WordCarlo BalzereitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Illegal Gold Mines in The PhilippinesDokument2 SeitenIllegal Gold Mines in The PhilippinesMaricar RamirezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Relationship Between Maternal Characteristics and Postpartum Hemorrhage: A Meta-Analysis StudyDokument11 SeitenRelationship Between Maternal Characteristics and Postpartum Hemorrhage: A Meta-Analysis Study16.11Hz MusicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guidelines On The Use of The Most Essential Learning Competencies (Melcs)Dokument11 SeitenGuidelines On The Use of The Most Essential Learning Competencies (Melcs)Alyssa AlbertoNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Hour of Prayer For The Coronavirus Pandemic PDFDokument4 SeitenAn Hour of Prayer For The Coronavirus Pandemic PDFVictor TettehNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Ii Defense ScriptDokument6 SeitenResearch Ii Defense ScriptLadiyyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Working in A Group EssayDokument4 SeitenWorking in A Group Essayjvscmacaf100% (2)

- Puskesmas Wanggudu Raya: Dinas Kesehatan Kabupaten Konawe UtaraDokument6 SeitenPuskesmas Wanggudu Raya: Dinas Kesehatan Kabupaten Konawe UtaraicaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Monday KordeDokument19 SeitenMonday KordeNational Press FoundationNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mentoring V Induction Programs 1Dokument6 SeitenMentoring V Induction Programs 1hstorresNoch keine Bewertungen

- SAG - Emergency Medical Services NC II (Amended 2013)Dokument5 SeitenSAG - Emergency Medical Services NC II (Amended 2013)Jaypz DelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Date: - : Parent Consent SlipDokument2 SeitenDate: - : Parent Consent SlipHero MirasolNoch keine Bewertungen

- SENIOR FIRST BROCHURE - Draft v7 - ProductsDokument6 SeitenSENIOR FIRST BROCHURE - Draft v7 - ProductsTrinetra AgarwalNoch keine Bewertungen