Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Fracture Vitamin D and Biophosphonates

Hochgeladen von

api-160688134Originalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Fracture Vitamin D and Biophosphonates

Hochgeladen von

api-160688134Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

FRACTURE, VITAMIN D AND BISPHOSPHONATES Dr Wilf Treasure 14/8/12 DEFINITIONS Osteoporosis is defined by bone mineral density more than

2.5 standard deviations below the young normal mean. Fragility fracture is a fracture occurring after a fall from standing height or less (SIGN 2003). BASELINE RISKS OF FRAGILITY FRACTURE In England and Wales, risk of fracture per person-decade was: averaged over a lifetime 10%; aged 50-59y 7% in men, 10% in women; aged 60-69y 6% in men, 13% in women; aged 70-79y 6% in men, 17% in women; aged 80-89y 8% in men, 22% in women (van Staa et al. 2001). After fragility fracture, women and men aged 60 to 69y had risk of re-fracture per person-decade of 37% (Center et al. 2007). After fragility vertebral fracture, women have risk of a further vertebral fracture within 1y of 19% (SIGN 2003). Ever-use of glucocorticosteroids increases the risk of fracture by a factor 2.6 aged 50y falling to 1.7 aged 85y explained only slightly by differences in bone densimetry (Kanis et al. 2004). PROBABILITY OF OSTEOPOROSIS IN PATIENTS WITH FRACTURES Of patients 50y with new fragility hip fracture, the probability of osteoporosis was 69% in women and 92% in men. Of patients 50y with new fragility fracture other than skull, face, hip or 2 vertebrae, the probability of osteoporosis was 34-56% in women and 5-40% in men (McLellan et al. 2003). RELATIVE BENEFITS OF VITAMIN D In people aged 65y daily vitamin D 800IU reduces non-vertebral fracture rate by 14% (BischoffFerrari et al. 2012) without side-effects (except for a slightly higher absolute risk of urinary stone) (Tice 2011). RELATIVE BENEFIT OF BISPHOSPHONATES In women with fracture and/or low densitometry bisphosphonates compared with placebo in multiple studies reduce risk of fracture by 0.2-0.6 - so by around 0.4 (SIGN 2003). There's no proven benefit from use of bisphosphonates beyond five years (L.-A. Fraser et al. 2011). PHARMACOLOGY OF VITAMIN D AND CALCIUM A one-cup serving of most dairy products contains 200-300 mg of calcium (Friedman & Brunton 2011); 700mg/d causes bloating, wind and constipation (Boots 2012); serious toxicity begins at 2000mg/d (Friedman & Brunton 2011). Vitamin D daily requirement is 2000-4000IU/d (Friedman & Brunton 2011); low-dose supplements cause no side-effects (Boots 2012); toxicity risk increases above 4000IU/d but is unlikely below 10000IU/d. For every increase in Vitamin D dose of 100IU/d, blood Vitamin D level increases by 2.5nmol/L (1ng/mL). Vitamin D blood levels of <30nmol/L (12ng/mL) are deficient and >50nmol/L (20ng/mL) are adequate: intermediate are indeterminate. Vitamin D treats rickets, osteomalacia, hypoparathyroidism and osteoporosis. Vitamin D prevents fractures but the relationship between blood vitamin D concentrations and fracture risk is unclear. The role of supplemental calcium in supporting skeletal integrity is controversial. Evidence for a role of supplemental vitamin D or calcium on non-skeletal outcomes is inconclusive (Friedman & Brunton

2011). MY PROVISIONAL CONCLUSIONS For acute treatment theres evidence supporting the use of vitamin D in rickets, osteomalacia, hypoparathyroidism and osteoporosis. The diagnosis and treatment of these conditions in the UK would probably involve specialists using various symptoms, signs and test results including blood vitamin D levels. For prevention of fracture, which is almost entirely within the remit of general practitioners, theres evidence supporting the use of vitamin D 800IU/d to produce a relative reduction in fracture rate of 14%. Calcium intake needs to be adequate but supplements cause side-effects (Boots 2012) and, I guess, reduce compliance. Absolute benefit and risk (of urinary stone) depend on prior probability of fracture and duration of use. The ratio of benefit to risk will therefore be greatest in those with osteoporosis, the elderly, those with poor diet, no sun and risk of falls and those with the shortest likely duration of use i.e. the housebound elderly. In my practice, therefore, it seems reasonable to make a start primary prevention by offering vitamin D supplements to women aged 80y without prior facture who'll have their risk of fracture over the next decade reduced from 22% to 19%, the number needed to supplement being 30. This prevention is not helped by doing blood tests. The most suitable preparations might be calcium and ergocalciferol 2 tabs daily (ergocalciferol 800IU = 20micrograms and calcium 194mg) plus dietary calcium. Alternatives are: Adcal-D3 2 daily (ergocalciferol 800IU = 20ug and calcium 1200mg); or Calcichew-D3 forte 2 daily ergocalciferol 800IU = 20ug and calcium 1000mg (BNF 2011). Fracture might be further prevented with bisphosphonates which are recommended for men and women with osteoporosis (SIGN 2003) and for woman 75y at high risk of fracture in circumstances where DEXA scanning is clinically inappropriate or unfeasible (NICE 2008) (such as in Shetland). It seems reasonable in my practice, therefore, to start secondary prevention by offering bisphosphonates for up to 5y along with vitamin D without DEXA scanning to men 75y with a history of fragility hip fracture and to men and women 75y with a history of multiple fragility vertebral fractures. For women with previous multiple fragility vertebral fractures the risk of fracture over the next year would be reduced from 19% to about 12%, with a number needed to treat of 14. POSTSCRIPT Ive just read a few papers and abstracts that emphasise the need to optimise calcium and vitamin D levels whether or not bisphosphonates are used (Poole & Compston 2012), the importance of proving any claimed benefit and harm from vitamin D before prescribing (Harvey & Cyrus Cooper 2012), and the unreliability of the evidence relating to at best small benefit from bisphosphonates (TI 2011a), (TI 2011b). Ive also received a detailed response for which Im grateful to a query I sent to Dr Alison Black (Black 2012). This letter led me indirectly to NHS Grampian prescribing newsletter Impact (Black & MacDonald 2012). These documents are commentaries and recommendations and dont give evidence not provided elsewhere. REFERENCES Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A. et al., 2012. A pooled analysis of vitamin D dose requirements for fracture prevention. The New England journal of medicine, 367(1), pp.4049.

Black, A., 2012. Fragility Fracture. Black, A. & MacDonald, A., 2012. Calcium and Vitamin D supplementation in the prevention of fracture: practical prescribing. Impact, 6(Feb 2012). Available at: http://www.nhsgrampian.com/grampianfoi/files/IMPACT_v6_002.pdf [Accessed August 14, 2012]. BNF, 2011. British National Formulary, Pharmaceutical Press. Available at: http://bnf.org/bnf/bnf/current/. Boots, 2012. Boots. Available at: http://www.boots.com. Center, J.R. et al., 2007. Risk of subsequent fracture after low-trauma fracture in men and women. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association, 297(4), pp.387394. Fraser, L.-A. et al., 2011. Fracture risk associated with continuation versus discontinuation of bisphosphonates after 5 years of therapy in patients with primary osteoporosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management, 7, pp.157166. Friedman, P.A. & Brunton, L.L., 2011. Updated Vitamin D and Calcium Recommendations. Available at: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/738275. Harvey, N.C. & Cooper, Cyrus, 2012. Vitamin D: some perspective please. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 345, p.e4695. Kanis, J.A. et al., 2004. A Meta-Analysis of Prior Corticosteroid Use and Fracture Risk. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 19(6), pp.893899. McLellan, A.R. et al., 2003. The fracture liaison service: success of a program for the evaluation and management of patients with osteoporotic fracture. Osteoporosis International: A Journal Established As Result Of Cooperation Between The European Foundation For Osteoporosis And The National Osteoporosis Foundation Of The USA, 14(12), pp.1028 1034. NICE, 2008. Alendronate, etidronate, risedronate, raloxifene, strontium ranelate and teriparatide for the secondary prevention of osteoporotic fragility fractures in postmenopausal women (NICE technology appraisal guidance 161). NICE. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/11748/42508/42508.pdf [Accessed May 30, 2012]. Poole, K.E. & Compston, J.E., 2012. Bisphosphonates in the treatment of osteoporosis. BMJ, 344(may22 1), pp.e3211e3211. SIGN, 2003. Management of Osteoporosis, SIGN. Available at: http://www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/fulltext/71/index.html [Accessed May 15, 2012]. van Staa, T.P. et al., 2001. Epidemiology of fractures in England and Wales. Bone, 29(6), pp.517 522.

TI, 2011a. A systematic review of the efficacy of bisphosphonates, The University of British Columbia: Department of Pharmacology and Department of Family Practice. Available at: http://ti.ubc.ca/letter83 [Accessed August 12, 2012]. TI, 2011b. A systematic review of the harms of bisphosphonates, The University of British Columbia: Department of Pharmacology and Department of Family Practice. Available at: http://www.ti.ubc.ca/letter84 [Accessed August 12, 2012]. Tice, J.A., 2011. Vitamin D for the Prevention of Osteoporotic Fractures: A Technology Assessment, California Technology Assessment Forum. Available at: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/744333 [Accessed February 25, 2012].

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Joint Pain TreatmentDokument3 SeitenJoint Pain Treatmentapi-160688134Noch keine Bewertungen

- Swidder Future Meetings For WebsiteDokument1 SeiteSwidder Future Meetings For Websiteapi-160688134Noch keine Bewertungen

- GoutDokument2 SeitenGoutapi-160688134Noch keine Bewertungen

- CancersDokument1 SeiteCancersapi-160688134Noch keine Bewertungen

- Anticipatory Care Plan 2013 05 08Dokument3 SeitenAnticipatory Care Plan 2013 05 08api-160688134Noch keine Bewertungen

- GoutDokument2 SeitenGoutapi-160688134Noch keine Bewertungen

- ProbioticsDokument1 SeiteProbioticsapi-160688134Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ppi LeafletDokument1 SeitePpi Leafletapi-160688134Noch keine Bewertungen

- Medication Guide For Patients by BNF SectionDokument27 SeitenMedication Guide For Patients by BNF Sectionapi-160688134Noch keine Bewertungen

- OsteoparesisDokument2 SeitenOsteoparesisapi-160688134Noch keine Bewertungen

- CancersDokument1 SeiteCancersapi-160688134Noch keine Bewertungen

- Medication Guide For Patients by BNF SectionDokument27 SeitenMedication Guide For Patients by BNF Sectionapi-160688134Noch keine Bewertungen

- Medication Guide For Patients by Medication GroupDokument28 SeitenMedication Guide For Patients by Medication Groupapi-160688134Noch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Six SigmaDokument4 SeitenSix SigmaPrateik BhasinNoch keine Bewertungen

- DPT CurriculumDokument3 SeitenDPT CurriculumDr. AtiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journey To A DiagnosisDokument4 SeitenJourney To A DiagnosisMark HayesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing 212 Final Exam Review - Fall 2017Dokument12 SeitenNursing 212 Final Exam Review - Fall 2017Marc LaBarbera100% (1)

- Sources of Drug InformationDokument36 SeitenSources of Drug InformationCristine ChubiboNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final DraftDokument5 SeitenFinal Draftapi-451064930Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2441-3300 Kneehab Phy Brochure 2r16Dokument2 Seiten2441-3300 Kneehab Phy Brochure 2r16MVP Marketing and DesignNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thyroid Disorders Part II Hypothyroidism and Thyroiditis LIttle 2006Dokument6 SeitenThyroid Disorders Part II Hypothyroidism and Thyroiditis LIttle 2006Jing XueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Medical Technology: Education & Career GuideDokument64 SeitenPhilippine Medical Technology: Education & Career GuideLovely Reianne ManigbasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Osce Stations - Blogspot.com Paediatric Respiratory ExamDokument2 SeitenOsce Stations - Blogspot.com Paediatric Respiratory ExamrohitNoch keine Bewertungen

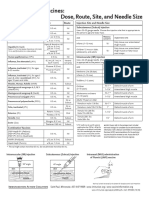

- Injection Site and Needle Size Vaccine Dose RouteDokument1 SeiteInjection Site and Needle Size Vaccine Dose RouteDr Ambana GowdaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arabic WordsDokument17 SeitenArabic WordsWEBSTER LOPEZNoch keine Bewertungen

- The National AIDS Council in Collaboration With The Ministry of Primary and Secondary 2018 QuizDokument7 SeitenThe National AIDS Council in Collaboration With The Ministry of Primary and Secondary 2018 QuizFelistus TemboNoch keine Bewertungen

- Surgical Training For Austere Environments: Course DirectorDokument7 SeitenSurgical Training For Austere Environments: Course Directorioannis229Noch keine Bewertungen

- Argumentative Essay FinalDokument3 SeitenArgumentative Essay Finalapi-248602269Noch keine Bewertungen

- Terapi Seft Spiritual Emotional Freedom TechniqueDokument7 SeitenTerapi Seft Spiritual Emotional Freedom TechniqueWiwik AristianiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Community Health Nursing (Learning Feedback Diary (LFD #23)Dokument2 SeitenCommunity Health Nursing (Learning Feedback Diary (LFD #23)Angelica Malacay RevilNoch keine Bewertungen

- 16CB01OIC0628Dokument38 Seiten16CB01OIC0628Satish GuptaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kemampuan Clinical Reasoning Pada Ujian Osce Mahasiswa Kedokteran Tahun KetigaDokument9 SeitenKemampuan Clinical Reasoning Pada Ujian Osce Mahasiswa Kedokteran Tahun Ketigabelahan jiwaNoch keine Bewertungen

- About Tattoos What Is A Tattoo?Dokument2 SeitenAbout Tattoos What Is A Tattoo?Çağatay SarıkayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- OGDokument385 SeitenOGMin MawNoch keine Bewertungen

- Retained PlacentaDokument3 SeitenRetained PlacentaDeddy AngNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clubfoot Deformities ExplainedDokument3 SeitenClubfoot Deformities ExplainedKim GalamgamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Funda Lab - Prelim ReviewerDokument16 SeitenFunda Lab - Prelim ReviewerNikoruNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guidelines For Toxicity/safety Profile Evaluation of Ayurved & Siddha, Plant DrugsDokument5 SeitenGuidelines For Toxicity/safety Profile Evaluation of Ayurved & Siddha, Plant DrugsPRAKASH DESHPANDENoch keine Bewertungen

- Alopecia Areata and Psoriasis Vulgaris Associated With TSDokument3 SeitenAlopecia Areata and Psoriasis Vulgaris Associated With TSILham SyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Euthanasia and Assisted SuicideDokument14 SeitenEuthanasia and Assisted Suicideapi-314071146Noch keine Bewertungen

- OET Writing Referral Letter for Michelle BennettDokument3 SeitenOET Writing Referral Letter for Michelle BennettJigesh JosephNoch keine Bewertungen

- Urinary Tract InfectionDokument2 SeitenUrinary Tract InfectionAnonymous KillerNoch keine Bewertungen

- ICD 10 BasicsDokument16 SeitenICD 10 Basicssvuhari100% (1)