Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Synthesis Paper Thematic Teaching Rev

Hochgeladen von

api-203221125Originalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Synthesis Paper Thematic Teaching Rev

Hochgeladen von

api-203221125Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Running head: Thematic Teaching

Synthesis Paper Thematic Teaching: Benefits and Practices Heather Bloxham Educ 410 Integration Seminar March 8, 2013

Running head: Thematic Teaching

The population of English Language Learners (ELL) is growing exponentially in many urban and rural settings throughout Canada. It is essential for teachers to be equipped with tools to meet the needs of this growing diverse demographic. Good intentions and just good teaching are no longer enough to truly help these students reach their potential. In this paper I will explore the importance of thematic teaching. I will discuss specific attributes that enhance thematic teaching such as storybook reading, guided practice and differentiated lesson. I will also use this paper as a springboard to discuss the important role thematic teaching plays in Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency Skills (CALPS). Through exploring these topics I endeavor to shed light on techniques and concepts that will bolster the academic success of many ELL students. It must be noted, even though this paper focuses specifically on the needs of ELL students, the strategies and concepts explored will undoubtedly benefit Native speaking students as well. Thematic lessons provide real language, real reason, and real purpose to lessons. These lessons help to provide students, specifically ELL students, with authentic learning experiences that are extremely meaningful. Thematic learning begins with a topic or subject, from which many other activities then anch out from this central idea. Thematic planning provides incidental learning, intentional learning and independent learning (Hetty Roessingh, Educ 410 Course Lecture, 2013). This allows teachers the flexibility to be creative, but also lets the teacher to plan with intent (Hetty

Running head: Thematic Teaching Roessingh, Educ 410 Course Lecture, 2013). Thematic lessons build on students background knowledge and interests (Goldenberg, 2008). By tapping into background knowledge, thematic lessons provide a platform for students to discuss their own experiences, which in turn encourages student conversations related to theme or text (Hickman, Pollard-Durodola & Vaughn, 2004). Peer-to-peer conversations help personalize the learning, as well as enhance students understanding of the topic (Hickman et al., 2004). The goal of thematic teaching is to build on students existing

knowledge construct vocabulary. A classroom lesson that leaves with the student is one a student will be able to internalize and apply to everyday life and future learning. One key aspect of thematic teaching is storybook reading. Read-aloud practices at home as well as in school are very effective in vocabulary building (Pikulski & Templeton, 2004). Repeated storybook reading promotes incidental learning, which implies students will not only acquire grammar, they will also acquire a great deal of vocabulary (Ulanoff & Pucci, 1999). Developing a rich vocabulary at a young age will aid students in their future vocabulary development in higher grades. A strong vocabulary to draw on will allow students to infer the meanings of new words (James B. Hale, Educ 406 Course Lecture, 2013). Although storybook reading is key to vocabulary development, those who lack experience with stories may have their interest diverted away from learning new words, and instead their interests may lean towards learning the fundamentals of story structure (plot or characters) (Collins, 2010). This however is not a drawback for language learners, as students can benefit from both processes (Collins, 2010). The initial lag in vocabulary development will grow once learners gain more exposure to, and become more interested in, the stories they are reading or hearing.

Running head: Thematic Teaching Storybook reading can be the springboard for many lesson adaptations (a central idea of thematic lesson planning). Reading can introduce role-playing and introduce realia1 to students. These aspects can add interest and even make an ordinary lesson memorable through active participation. Because of the nature of thematic lessons, ELLs will not

only hear more words, they will also retain them. This vocabulary retention is due to the words being embedded in meaningful contexts with many opportunities for repetition (Goldenberg, 2008). Ideas are presented in multiple fashions, allowing students to work under the same understanding but progress with different levels of support, challenge or complexity (Tomlinson, 2000). This restructuring allows for topics to be absorbed and avoids boredom or the feeling of punishment for having to do something over and over (Ulanoff & Pucci, 1999). The repetition of thematic lesson works well in situations where there are individual and group differences. With all students, ELL or otherwise, there will be individual and group differences that need to be taken into consideration when planning a lesson (Goldenberg, 2008). Thematic lessons are ideal when these differences exist (Tomlinson, 2000). Thematic lessons foster all aspects of teachings designed to cater to the mixed abilities of students. The layers within the thematic lesson can provide opportunities for teachers to use corrective feedback and guided practice (Ulanoff & Pucci, 1999). Guided practice provides scaffolding for students to learn and grow with support. Research has found that guided practice achieved better outcomes for student vocabulary development than did free writing opportunities (Goldenberg, 2008). However, students who have developed large vocabularies may be reluctant to use them without assistance from

1

Realia are objects and materials from everyday life that are used for teaching aids such as photos, dishes, ornaments or tools.

Running head: Thematic Teaching teachers (Pikulski &Templeton, 2004). Additionally, the fear of failure may prevent students from taking risks or getting creative. Alongside guided practice is corrective feedback, which is essential for students improvement. With corrective feedback students learn to correct their mistakes, and within a thematic lesson students have opportunities to show their improvements and deepen their understanding. Through QARs, students improve comprehension and learn how to look at text critically. QARs aid students in thinking creatively and cooperatively while challenging them to use

higher-level thinking skills (intnetaldfjladsj). These three practice are critical for students to develop further skills that will build their CALPS (Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency Skills) proficiency. English Learning instruction is a longer, harder, more complex process than many teachers believe (McLaughlin, 1992). English Language learners can sound good with their BICS (Basic Interpersonal Conversation Skills), but they lack the academic English or CALPS (Roessingh & Elgie, 2009). Everyday conversational English can be acquired at a reasonable proficiency in just two to three years, but academic English can require six or seven years, if not longer, to obtain (Goldenberg, 2008). An article in the Calgary Herald quotes Dr. Roessingh, an expert in English Language Instruction, who states students who are chatty appear just as adept with English as other children (Cuthbertson, 2013). However, their proficiency is superficial and they lack a well-rounded vocabulary that matches their native speaking peers (Cuthbertson, 2013). This vocabulary deficit will only grow with time if teachers are not using appropriate strategies, such as thematic lessons (Cuthbertson, 2013). Thematic lessons can begin the process of developing rich vocabularies that will produce academic

Running head: Thematic Teaching benefits for students.

Learners lacking CALPS do not have the skills to understand inflections of words and their appropriate use; as well they lack the vocabulary that is needed for future success in higher grades and within their jobs or post-secondary educations (Goldenberg, 2008). ELLs need academic content instruction in addition to - not instead of English language development (Goldenberg, 2008). Students who are able to master CALPS will unquestionably have a unique advantage in their technical or professional careers (McLaughlin, 1992). Even though this language base is essential for school success, it is difficult to ELLs to acquire (Goldenberg, 2008). Unfortunately, students exposure to CALPS is limited as it goes beyond conversational English and therefore is not generally used outside the classroom (Goldenberg, 2008). Through thematic lessons teachers can build vocabularies and develop CALPS within their ELL students. Thematic lessons are so crucial to the development of CALPS because they draw out new vocabulary, complex sentence structures, and with use of QARs (Question Answer Relationships) allow students to reflect and deepen their understanding of the topic (Goldenberg, 2008). Thematic lessons build CALPS and provide students with the tools to communicate. These tools to connect can be used in real-life situations, or to excel in academics and pursue careers that are beyond the BICS level. Achievement in and out of school hinges on building BICS and CALPS. If an ELL learner is not provided with meaningful, authentic experiences, these students may wonder what the purpose is of learning beyond rudimentary skills, if they feel they can get by with BICS and their first language. (Hetty Roessingh, Educ 410 Course Lecture, 2013). The notion of just getting by is not only short sighted but it illuminates the reason thematic

Running head: Thematic Teaching

learning is so beneficial for ELLs. If a student plays a role in their learning they are going to be more engaged. Good intentions are no longer enough to effectively teach language learners, or any child for that matter. To better prepare ELLs for academic success, teachers must also be better prepared. Teachers who skillfully recycle key concepts will provide

meaningful experiences, build vocabulary, and deepen students understandings of subjects (Goldenberg, 2008). Teachers using thematic lessons will be better equipped to reach ELLs (Cuthbertson, 2013). Thematic teaching practices enhance students learning by engaging them with their peers in authentic communication. By using thematic strategies that build on students interests and background knowledge, understandings are entrenched. Lesson approaches under the umbrella of thematic teaching such as guided practice and storybook reading improve performance, participation and vocabulary development. Guided practice and QARs enable students to take risks, think critically and be creative. Young students who develop a rich vocabulary will set the stage for further confidence in vocabulary development. Through thematic teaching, instructors

can plan with intent while fostering student interest, creativity and risk-taking while building a strong foundation of academic language that reaches beyond basic conversational skills.

Running head: Thematic Teaching

References Collins, M. (2009). ELL preschoolers English vocabulary acquisition from storybook reading. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 25, 84-97. Retrieved March 4, 2013 from, http://ac.els-cdn.com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/ Cuthbertson,R., (2013) Influx of immigrants puts schools English literacy instruction to the test. Calgary Herald. Retrieved March 4, 2013 from,http://www.calgaryherald.com/story_print.html?id=7793060&sponsor=curri ebarracks Goldenberg, C. (2008). Teaching English language learners: What the research does and does not say. American Educator, Summer, 2008, 8-23. http://www.aft.org/pdfs/americaneducator/summer2008/goldenberg.pdf Hale, J. B. (2013). School Neuropsychology of Reading and Reading Disabilities Education 406 Course Powerpoints. Hickman, P., Pollard-Durodola, S., Vaughn, Sharon. (2004). Storybook reading:Improving vocabulary and comprehension for English-Language learners Retrieved March 3, 2013 from, http://faculty.weber.edu/mtungmala/hybrid4270/articles/storyreadvoc.pdf McLaughlin, B. (1992). Myths and misconceptions about second language learning:What every teacher needs to unlearn. Educational Practice Report 5. Retrieved March 2, 2013 from http://www.usc.edu/dept/education/CMMR/FullText/McLaughlinMyths.pdf Pikulski, J. & Templeton, S. (2004). Teaching and developing vocabulary: Key to longterm reading success. Current research in reading and language arts. Houghton Mifflin. Retrieved March 3, 2012, from http://www.eduplace.com/state/author/pik_temp.pdf QAR. (n.d.) Reading Rockets. Retrieved March 6, 2013, from http://www.readingrockets.org/strategies/question_answer_relationship/ Realia. (n.d.). Dictionary.com Unabridged. Retrieved March 06, 2013, from Dictionary.com website: http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/realia Roessingh, H. & Elgie, S. (2009). Early language and literacy development among young

Running head: Thematic Teaching ELL: Preliminary insights from a longitudinal study. TESL Canada Journal, 26(2), 24-45. Retrieved March 3, 2013, from, http://www.teslcanadajournal.ca/index.php/tesl/article/viewFile/413/243 Roessingh, H. (2013). Integration Seminar 1. Education 410 Course Lecture. Tomlinson, C.A., (2000). What Is Differentiated Instruction? Reading Topics A-Z Retrieved March 2, 2013 from, http://www.readingrockets.org/article/263/ Ulanoff, S.H. & Pucci, S.L. (1999). Learning new words from books: The effects of readaloud on second language vocabulary acquisition. Bilingual Research Journal, 23(4), 409 421. Retrieved March 2, 2013 from http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15235882.1999.10162743

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Sea Test InventoryDokument20 SeitenSea Test InventoryAndrew PauloNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Grade 5 Udl Unit Plan RevDokument10 SeitenGrade 5 Udl Unit Plan Revapi-203221125Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Power of The MindDokument17 SeitenThe Power of The MindNanette Aumentado - Peñamora100% (1)

- Lesson Plan Teaches Egyptian Pyramids VocabularyDokument8 SeitenLesson Plan Teaches Egyptian Pyramids VocabularyVlad VargauNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mru Transitional Vocational ProgramDokument1 SeiteMru Transitional Vocational Programapi-203221125Noch keine Bewertungen

- Daily ScheduleDokument1 SeiteDaily Scheduleapi-203221125Noch keine Bewertungen

- Healthy Relationships Event Poster - MartindaleDokument1 SeiteHealthy Relationships Event Poster - Martindaleapi-203221125Noch keine Bewertungen

- December ScheduleDokument2 SeitenDecember Scheduleapi-203221125Noch keine Bewertungen

- November ScheduleDokument4 SeitenNovember Scheduleapi-203221125Noch keine Bewertungen

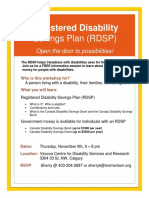

- RDSP Workshop - Nov 9 2017Dokument1 SeiteRDSP Workshop - Nov 9 2017api-203221125Noch keine Bewertungen

- Students 372 FinalDokument2 SeitenStudents 372 Finalapi-203221125Noch keine Bewertungen

- Students 311 FinalDokument1 SeiteStudents 311 Finalapi-203221125Noch keine Bewertungen

- PhilosophyDokument5 SeitenPhilosophyapi-203221125Noch keine Bewertungen

- Disability Tax Credit FormDokument6 SeitenDisability Tax Credit Formapi-203221125Noch keine Bewertungen

- Westcast 2014 Letter of Reference HeatherDokument1 SeiteWestcast 2014 Letter of Reference Heatherapi-203221125Noch keine Bewertungen

- Students 309 FinalDokument2 SeitenStudents 309 Finalapi-203221125Noch keine Bewertungen

- Bloxham Heather - Resume 2014Dokument2 SeitenBloxham Heather - Resume 2014api-203221125Noch keine Bewertungen

- RubricDokument1 SeiteRubricapi-203221125Noch keine Bewertungen

- Udl Unit Planning Chart-2Dokument14 SeitenUdl Unit Planning Chart-2api-203221125Noch keine Bewertungen

- 407 Bloxham Heather Reflections On DiversityDokument5 Seiten407 Bloxham Heather Reflections On Diversityapi-203221125Noch keine Bewertungen

- 535 CalendarDokument1 Seite535 Calendarapi-203221125Noch keine Bewertungen

- Story Prediction The Hockey SweaterDokument2 SeitenStory Prediction The Hockey Sweaterapi-203221125Noch keine Bewertungen

- GoldenbergellDokument19 SeitenGoldenbergellapi-203221125Noch keine Bewertungen

- Field Experience Paper - Is Pop Culture Used in SchoolsDokument10 SeitenField Experience Paper - Is Pop Culture Used in Schoolsapi-203221125Noch keine Bewertungen

- Visual Metaphor RevisedDokument9 SeitenVisual Metaphor Revisedapi-203221125Noch keine Bewertungen

- How Second Language Learning OccursDokument7 SeitenHow Second Language Learning Occursapi-203221125Noch keine Bewertungen

- MythsDokument2 SeitenMythsapi-203221125Noch keine Bewertungen

- Letter Writing Sample - The Hockey SweaterDokument2 SeitenLetter Writing Sample - The Hockey Sweaterapi-203221125Noch keine Bewertungen

- A Day in The Life - The Hockey SweaterDokument3 SeitenA Day in The Life - The Hockey Sweaterapi-203221125Noch keine Bewertungen

- Who Am I As A Learning and Who Am I Becoming As A TeacherDokument6 SeitenWho Am I As A Learning and Who Am I Becoming As A Teacherapi-203221125Noch keine Bewertungen

- NLEPT Catalogue PDFDokument121 SeitenNLEPT Catalogue PDFHëłľ Śç BøÿNoch keine Bewertungen

- Do Children Learn Language Through AnalogyDokument3 SeitenDo Children Learn Language Through AnalogyLarasati Atkine CliffeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Multimedia Critique Paper #3 - EDpuzzleDokument3 SeitenMultimedia Critique Paper #3 - EDpuzzlekcafaro59Noch keine Bewertungen

- Final - Template of Performance StandardDokument1 SeiteFinal - Template of Performance StandardCry BeroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Entrepreneu Rial Cognition: Understanding How Entrepreneurs ThinkDokument16 SeitenEntrepreneu Rial Cognition: Understanding How Entrepreneurs ThinkBianca EtcobañezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cognitive biases for anger-related stimuli in individuals with high trait angerDokument79 SeitenCognitive biases for anger-related stimuli in individuals with high trait angerAdiba MasterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Foundations of Individual BehaviourDokument8 SeitenFoundations of Individual Behaviourkomal4242Noch keine Bewertungen

- Reading As A ProcessDokument29 SeitenReading As A ProcessDianne SibolboroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Expert Judgement Checklist of Learning Media "E-Writing": 1 (Poor) 2 (Enough) 3 (Good) 4 (Very Good) 5 (Excellent)Dokument3 SeitenExpert Judgement Checklist of Learning Media "E-Writing": 1 (Poor) 2 (Enough) 3 (Good) 4 (Very Good) 5 (Excellent)Sari DewiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Depression:-: Bipolar-I Disorder Bipolar-Ii Disorder Cyclothymic DisorderDokument1 SeiteDepression:-: Bipolar-I Disorder Bipolar-Ii Disorder Cyclothymic DisorderAli NawazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Artificial IntelligenceDokument17 SeitenArtificial IntelligenceArfaan XhAikhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 12 Academic EnglishDokument21 SeitenLesson 12 Academic EnglishJellie OpisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Daily Lesson Plan in Music 10 Quarter 4 Teaching Date: February, 2018Dokument3 SeitenDaily Lesson Plan in Music 10 Quarter 4 Teaching Date: February, 2018Lhena Manzano GoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wray Alison Formulaic Language Pushing The BoundarDokument5 SeitenWray Alison Formulaic Language Pushing The BoundarMindaugas Galginas100% (1)

- Toefl iBT Test: Integrated Speaking Rubrics (Scoring Standards)Dokument1 SeiteToefl iBT Test: Integrated Speaking Rubrics (Scoring Standards)amzeidanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Week 3: Explicit Teaching of Grammar TechniquesDokument4 SeitenWeek 3: Explicit Teaching of Grammar TechniquesFarah HarisNoch keine Bewertungen

- 03 A Critique of Skinner's Views On The Explanatory Inadequacy of Cognitive TheoriesDokument19 Seiten03 A Critique of Skinner's Views On The Explanatory Inadequacy of Cognitive TheoriesJonathanNoch keine Bewertungen

- PPST Module 1-14 SummaryDokument2 SeitenPPST Module 1-14 SummaryLEONORA DALLUAYNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ts25 Daily Lesson Plan: Science 0810-0910Dokument2 SeitenTs25 Daily Lesson Plan: Science 0810-0910Magdeline MenggingNoch keine Bewertungen

- PerceptionDokument15 SeitenPerceptionशिशिर ढकालNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Review of Neuropsychological and Neuroimaging Research in Autistic Spectrum Disorders: Attention, Inhibition and Cognitive FlexibilityDokument16 SeitenA Review of Neuropsychological and Neuroimaging Research in Autistic Spectrum Disorders: Attention, Inhibition and Cognitive FlexibilityQuetzaly HernándezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cuc Lesson Plan Design 2014 Adapted For 1070Dokument3 SeitenCuc Lesson Plan Design 2014 Adapted For 1070api-253426503Noch keine Bewertungen

- Activity 3 Public Speaking and Debate, Edric Kyle RomarateDokument3 SeitenActivity 3 Public Speaking and Debate, Edric Kyle RomarateEdric Kyle V. RomarateNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1st Year LIT Pupils Survey ResultsDokument4 Seiten1st Year LIT Pupils Survey ResultsSalem Zemali100% (1)

- Journal Entry WritingDokument3 SeitenJournal Entry WritingsyazwanazhariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Choice Theory and Goal Theory ComparedDokument2 SeitenChoice Theory and Goal Theory ComparedChristian RacomaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jbbs 2020012115154201Dokument10 SeitenJbbs 2020012115154201Soporte CeffanNoch keine Bewertungen