Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

The Miranda Doctrine PDF

Hochgeladen von

pilosopotacio2013Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The Miranda Doctrine PDF

Hochgeladen von

pilosopotacio2013Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

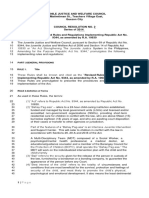

Miranda Doctrine

Under this doctrine, prior to any questioning during custodial investigation, the person must be warned that he has a right to remain silent, that any statement he gives may be used as evidence against him, and that he has the right to the presence of an attorney, either retained or appointed. The defendant may waive effectuation of these rights, provided the waiver is made voluntarily, knowingly, and intelligently. This doctrine originated from the 1966 case of Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966). In this case, the US Supreme Court: . . . established rules to protect a criminal defendant's privilege against self-incrimination from the pressures arising during custodial investigation by the police. Thus, to provide practical safeguards for the practical reinforcement for the right against compulsory self-incrimination, the Court held that "the prosecution may not use statements, whether exculpatory or inculpatory, stemming from custodial interrogation of the defendant unless it demonstrates the use of procedural safeguards effective to secure the privilege against self-incrimination." It was suggested therein that "Prior to any questioning, the persons must be warned that he has a right to remain silent, that any statement he does make may be used as evidence against him, and that he has a right to the presence of an attorney, either retained or appointed." As explained in Miranda, "The need for counsel in order to protect the privilege (against selfincrimination) exists for the indigent as well as the affluent * * * . While authorities are not required to relieve the accused of his poverty, they have the obligation not to take advantage of indigence in the administration of justice * * * . In order to fully apprise a person interrogated of the extent of his rights under this system then, it is necessary to warn him not only that he has the right to consult with an attorney, but also that if he is indigent a lawyer will be appointed to represent him

Constitutional Basis

The Constitution even adds the more stringent requirement that the waiver must be in writing and made in the presence of counsel. Section 12, Article III of the Constitution reads: SEC. 12. (1) Any person under investigation for the commission of an offense shall have the right to be informed of his right to remain silent and to have competent and independent counsel preferably of his own choice. If the person cannot afford the services of counsel, he must be provided with one. These rights cannot be waived except in writing and in the presence of counsel. (2) No torture, force, violence, threat, intimidation, or any other means which vitiate the free will shall be used against him. Secret detention places, solitary, incommunicado, or other similar forms of detention are prohibited. (3) Any confession or admission obtained in violation of this or Section 17 hereof shall be inadmissible in evidence against him. (4) The law shall provide for penal and civil sanctions for violations of this section as well as compensation to and rehabilitation of victims of torture or similar practices, and their families.

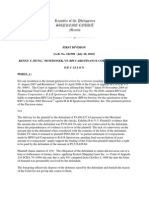

Miranda v. Arizona (384 U.S. 436)

In each of these cases, the defendant, while in police custody, was questioned by police officers, detectives, or a prosecuting attorney in a room in which he was cut off from the outside world. None of the defendants was given a full and effective warning of his rights at the outset of the interrogation process. In all four cases, the questioning elicited oral admissions, and, in three of them, signed statements as well, which were admitted at their trials. All defendants were convicted, and all convictions, except in No. 584, were affirmed on appeal. Held: 1. The prosecution may not use statements, whether exculpatory or inculpatory, stemming from questioning initiated by law enforcement officers after a person has been taken into custody or otherwise deprived of his freedom of action in any significant way, unless it demonstrates the use of procedural safeguards effective to secure the Fifth Amendment's privilege against self-incrimination. Pp. 444-491. (a) The atmosphere and environment of incommunicado interrogation as it exists today is inherently intimidating, and works to undermine the privilege against self-incrimination. Unless adequate preventive measures are taken to dispel the compulsion inherent in custodial surroundings, no statement obtained from the defendant can truly be the product of his free choice. Pp. 445-458. (b) The privilege against self-incrimination, which has had a long and expansive historical development, is the essential mainstay of our adversary system, and guarantees to the individual the "right to remain silent unless he chooses to speak in the unfettered exercise of his own will," during a period of custodial interrogation [p437] as well as in the courts or during the course of other official investigations. Pp. 458-465. (c) The decision in Escobedo v. Illinois, 378 U.S. 478, stressed the need for protective devices to make the process of police interrogation conform to the dictates of the privilege. Pp. 465-466. (d) In the absence of other effective measures, the following procedures to safeguard the Fifth Amendment privilege must be observed: the person in custody must, prior to interrogation, be clearly informed that he has the right to remain silent, and that anything he says will be used against him in court; he must be clearly informed that he has the right to consult with a lawyer and to have the lawyer with him during interrogation, and that, if he is indigent, a lawyer will be appointed to represent him. Pp. 467-473. (e) If the individual indicates, prior to or during questioning, that he wishes to remain silent, the interrogation must cease; if he states that he wants an attorney, the questioning must cease until an attorney is present. Pp. 473-474. (f) Where an interrogation is conducted without the presence of an attorney and a statement is taken, a heavy burden rests on the Government to demonstrate that the defendant knowingly and intelligently waived his right to counsel. P. 475. (g) Where the individual answers some questions during in-custody interrogation, he has not waived his privilege, and may invoke his right to remain silent thereafter. Pp. 475-476. (h) The warnings required and the waiver needed are, in the absence of a fully effective equivalent, prerequisites to the admissibility of any statement, inculpatory or exculpatory, made by a defendant. Pp. 476-477.

2. The limitations on the interrogation process required for the protection of the individual's constitutional rights should not cause an undue interference with a proper system of law enforcement, as demonstrated by the procedures of the FBI and the safeguards afforded in other jurisdictions. Pp. 479-491. 3. In each of these cases, the statements were obtained under circumstances that did not meet constitutional standards for protection of the privilege against self-incrimination. Pp. 491-499.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Ra 8353 Briefer PDFDokument2 SeitenRa 8353 Briefer PDFDhanny PosionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jessie O. Obongen Jr. BS - CRIM III BDokument3 SeitenJessie O. Obongen Jr. BS - CRIM III BJessie Obongen Jr.100% (1)

- Readings in The Philippine History v2019Dokument5 SeitenReadings in The Philippine History v2019Goog YubariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Week TwoDokument2 SeitenWeek TwoApple AsneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final Poly 5.the Polygraph Examiner Subject and Examination RoomDokument28 SeitenFinal Poly 5.the Polygraph Examiner Subject and Examination Roomkimberlyn odoñoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10 Basic Human Rights Standards For Law Enforcement OfficialsDokument32 Seiten10 Basic Human Rights Standards For Law Enforcement OfficialsAngel Joy CATALAN (SHS)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Parole and Probaton AdministrationDokument14 SeitenParole and Probaton AdministrationJunella MagnoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Amnesty in The PhilippinesDokument57 SeitenAmnesty in The PhilippinesFlor Clores-Gonzalo86% (14)

- Enterprise CrimeDokument23 SeitenEnterprise Crimelindseyg89100% (2)

- PNP Guidebook On Human RightsDokument79 SeitenPNP Guidebook On Human RightsSkier Mish100% (1)

- BJMP Comprehensive Operations Manual 2015Dokument12 SeitenBJMP Comprehensive Operations Manual 2015Patrick RodriguezNoch keine Bewertungen

- HOUSE BILL NO. - : Eighteenth CongressDokument6 SeitenHOUSE BILL NO. - : Eighteenth Congressfatima ramos0% (1)

- I. Revised Penal Code - Book 1: 2019 Criminal Law Bar ExaminationsDokument33 SeitenI. Revised Penal Code - Book 1: 2019 Criminal Law Bar ExaminationsAnie Guiling-Hadji GaffarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Technical English 2Dokument57 SeitenTechnical English 2ricamegaringrodriguez16Noch keine Bewertungen

- Human Rights EducationDokument18 SeitenHuman Rights EducationJaypee Bitun EstalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cases - Quantum of EvidenceDokument13 SeitenCases - Quantum of EvidenceCzarina CidNoch keine Bewertungen

- The National Bureau of InvestigationDokument17 SeitenThe National Bureau of InvestigationLowie Jay Mier OrilloNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1CDI 1 OkDokument6 Seiten1CDI 1 OkJanbert SuarezNoch keine Bewertungen

- PNP Core Values (Regency)Dokument32 SeitenPNP Core Values (Regency)rhasdy AmingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case ScenarioDokument9 SeitenCase ScenarioJay-r Pabualan DacoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 8 People Vs OrdizDokument1 Seite8 People Vs Ordizmei atienzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rotc OrientationDokument11 SeitenRotc OrientationCeasar EstradaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency: 2.1. LogoDokument8 SeitenPhilippine Drug Enforcement Agency: 2.1. LogoJerrymiah.maligon67% (3)

- The Philippine Rule On DNA EvidenceDokument41 SeitenThe Philippine Rule On DNA EvidenceRose SabadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Second PillarDokument30 SeitenThe Second Pillarvee100% (3)

- Philippine Criminal Justice System and Human RightsDokument6 SeitenPhilippine Criminal Justice System and Human Rightsjim peterick sisonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Larry - Character FormationDokument2 SeitenLarry - Character FormationKhristel AlcaydeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Rudimentary Square of Crime - Final PDFDokument14 SeitenThe Rudimentary Square of Crime - Final PDFgodyson dolfoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 2.SG 2-CLJ 1 - IpcjsDokument18 SeitenModule 2.SG 2-CLJ 1 - IpcjsDJ Free Music100% (1)

- Chapter 1 Characteristics-Of-Good-Police-Report-A-Police-Report-Is-A-Chronological-Account-Of-An-Incident-That-Happened-AtDokument2 SeitenChapter 1 Characteristics-Of-Good-Police-Report-A-Police-Report-Is-A-Chronological-Account-Of-An-Incident-That-Happened-AtElaiza Kathrine CleofeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Judicial System of The PhilippinesDokument5 SeitenJudicial System of The PhilippinesJacquelyn LopezNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2.2 History of ProsecutionDokument5 Seiten2.2 History of Prosecutionjae eNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anti CarnappingDokument36 SeitenAnti CarnappingDolores PulisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bureau of CorrectionsDokument6 SeitenBureau of CorrectionsLexa L. DotyalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Test Yourself: "I" (My Individual Identity) "Me" (Others Expectation of ME)Dokument2 SeitenTest Yourself: "I" (My Individual Identity) "Me" (Others Expectation of ME)ethan philasiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pp. vs. Albior Case DigestDokument2 SeitenPp. vs. Albior Case Digestunbeatable38100% (1)

- Hist 9Dokument1 SeiteHist 9Jestoni JuanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Executive ClemencyDokument8 SeitenExecutive ClemencyJuneil MeredoresNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1987 Constitution: Ms. Claudine Saddul Uanan HSC Faculty For Social SciencesDokument7 Seiten1987 Constitution: Ms. Claudine Saddul Uanan HSC Faculty For Social SciencesClaudine UananNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine ConstabularyDokument2 SeitenPhilippine ConstabularyEvans MacabentaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Notes-IRF and BlotterDokument8 SeitenNotes-IRF and BlotterCharity EsmeroNoch keine Bewertungen

- CLJ5 - Evidence Module 3: Rule 129: What Need Not Be Proved Topic: What Need Not Be ProvedDokument9 SeitenCLJ5 - Evidence Module 3: Rule 129: What Need Not Be Proved Topic: What Need Not Be ProvedSmith BlakeNoch keine Bewertungen

- RII of RA 9344 As Amended by RA 10630Dokument63 SeitenRII of RA 9344 As Amended by RA 10630filibertpatrick_tad-awan100% (1)

- Publicorder CrimePreventionDokument16 SeitenPublicorder CrimePreventionMelodiah JoiNoch keine Bewertungen

- CE 2 Module 1Dokument15 SeitenCE 2 Module 1PanJan Bal100% (1)

- NapolcomDokument3 SeitenNapolcomGla IreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Static GroupDokument4 SeitenStatic GroupNemesia Ishi RamosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stress Management Among Police Officers in Bislig City, PhilippinesDokument5 SeitenStress Management Among Police Officers in Bislig City, PhilippinesIvylen Gupid Japos CabudbudNoch keine Bewertungen

- Relevant LawsDokument1 SeiteRelevant Lawsjae e100% (2)

- General Concepts of CharacterDokument1 SeiteGeneral Concepts of CharacterVincent VingnoNoch keine Bewertungen

- CSI Form 2 Request For The Conduct of SOCO 2Dokument1 SeiteCSI Form 2 Request For The Conduct of SOCO 2Grena Delos ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- B. Narrative Report About PdeaDokument3 SeitenB. Narrative Report About PdeaSophia JoppaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Affidavit of Understanding: Signature Over Printed Name of Parent/GuardianDokument1 SeiteAffidavit of Understanding: Signature Over Printed Name of Parent/GuardianDunn NobleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Salient Features RA 9344Dokument42 SeitenSalient Features RA 9344Manilyn B CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Effectiveness of Physical Security of Provincial Rehabilitaton Andreformatory Center in Mati CityDokument23 SeitenThe Effectiveness of Physical Security of Provincial Rehabilitaton Andreformatory Center in Mati Cityangeline OriasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philo 10 Ethics (Siec)Dokument3 SeitenPhilo 10 Ethics (Siec)Rudy CamayNoch keine Bewertungen

- CLJ 15 EvidenceDokument35 SeitenCLJ 15 EvidenceHersheykris PimentelNoch keine Bewertungen

- My Final Reflection Paper About Being An Ojt Student in Barangay Nangka 1Dokument3 SeitenMy Final Reflection Paper About Being An Ojt Student in Barangay Nangka 1arway palceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Edquilang Research Custodial InterrogationDokument5 SeitenEdquilang Research Custodial InterrogationmacebaileyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Miranda V ArizonaDokument37 SeitenMiranda V ArizonaOlek Dela CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- PO 7300000152 Bajrang WireDokument6 SeitenPO 7300000152 Bajrang WireSM AreaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bayla v. Silang Traffic Co. Inc.Dokument2 SeitenBayla v. Silang Traffic Co. Inc.James Evan I. ObnamiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Domingo V People (Estafa)Dokument16 SeitenDomingo V People (Estafa)Kim EscosiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ResearchPaperonSecurityLaw PDFDokument13 SeitenResearchPaperonSecurityLaw PDFTARA DEVINoch keine Bewertungen

- Warden Special Action To Overturn Transparently Invalid Order Suspending Free SpeechDokument19 SeitenWarden Special Action To Overturn Transparently Invalid Order Suspending Free SpeechRoy WardenNoch keine Bewertungen

- 272 - City of Iriga Vs CASURECODokument3 Seiten272 - City of Iriga Vs CASURECOanon_614984256Noch keine Bewertungen

- AMLA (RA 9160 As Amended by RA 10365)Dokument83 SeitenAMLA (RA 9160 As Amended by RA 10365)Karina Barretto AgnesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nba-Nbpa Cba (2011)Dokument510 SeitenNba-Nbpa Cba (2011)thenbpa100% (9)

- Barcelona Traction, Light and PowerDokument3 SeitenBarcelona Traction, Light and PowerPrincessAngelicaMorado100% (1)

- Duress - Undue InfluenceDokument11 SeitenDuress - Undue InfluenceAdiba KabirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Benny Hung v. Bpi Card Corporation - Credit Card CaseDokument9 SeitenBenny Hung v. Bpi Card Corporation - Credit Card Caserosellerbucog_437907Noch keine Bewertungen

- Tax2 - Ch1-5 Estate Taxes ReviewerDokument8 SeitenTax2 - Ch1-5 Estate Taxes ReviewerMaia Castañeda100% (15)

- OpedDokument7 SeitenOpedapi-300741926Noch keine Bewertungen

- Airbus A320Dokument14 SeitenAirbus A320radi8100% (7)

- BibliographyDokument16 SeitenBibliographymaryjoensNoch keine Bewertungen

- Air Asia ComplaintDokument29 SeitenAir Asia ComplaintPGurusNoch keine Bewertungen

- M & A - HarvardDokument38 SeitenM & A - HarvardMohammed Zubair BhatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- People vs. BautistaDokument3 SeitenPeople vs. BautistaRenceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civil Procedure Case DigestDokument1 SeiteCivil Procedure Case Digestkemsue1224Noch keine Bewertungen

- CBF 10 Motion For Provisional Dismissal For Failure To Present WitnessDokument3 SeitenCBF 10 Motion For Provisional Dismissal For Failure To Present WitnessAndro DayaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- SSIP SampleDokument6 SeitenSSIP SampleAngelo Delgado100% (6)

- Vicar International Corp vs. Feb Leasing Case DigestDokument3 SeitenVicar International Corp vs. Feb Leasing Case Digestkikhay11Noch keine Bewertungen

- Contract of Lease of Personal, Real Property, Contract of Sale of Real Propery, Personal Property (Bilateral), Quitlclaim in Labor CasesDokument14 SeitenContract of Lease of Personal, Real Property, Contract of Sale of Real Propery, Personal Property (Bilateral), Quitlclaim in Labor CasesNombs NomNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter One Extinction of ObligationsDokument46 SeitenChapter One Extinction of ObligationsHemen zinahbizuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Surya Prakash Khatri and Ors Vs Madhu Trehan and Od010566COM602944Dokument20 SeitenSurya Prakash Khatri and Ors Vs Madhu Trehan and Od010566COM602944Rishabh KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tor Star Code ConductDokument10 SeitenTor Star Code Conductjsource2007Noch keine Bewertungen

- Football The Legendary Game: Physical EducationDokument20 SeitenFootball The Legendary Game: Physical EducationDev Printing SolutionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Admit CardDokument1 SeiteAdmit Cardchanderp_15Noch keine Bewertungen

- Smart Hotel - KRS - Google - Translate - 2 PDFDokument7 SeitenSmart Hotel - KRS - Google - Translate - 2 PDFDavid HundeyinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lopez V Orosa and Plaza Theater G.R. Nos. L-10817-18Dokument3 SeitenLopez V Orosa and Plaza Theater G.R. Nos. L-10817-18newin12Noch keine Bewertungen