Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Heidegger’s Method of Formal Indication in Being and Time

Hochgeladen von

jrewingheroOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Heidegger’s Method of Formal Indication in Being and Time

Hochgeladen von

jrewingheroCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Man and World 30: 413430, 1997. c 1997 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands.

413

Heideggers formal indication: A question of method in Being and Time

RYAN STREETER

Department of Philosophy, Emory University, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA

Abstract. For Heidegger, phenomenological investigation is carried out by formal indication, the name given to the methodical approach he assumes in Being and Time. This paper attempts to draw attention to the nature of formal indication in light of the fact that it has been largely lost upon American scholarship (mainly due to its inconsistent translation). The roots of the concept of formal indication are shown in two ways. First, its thematic treatment in Heideggers 1921/22 Winter Semester course, Phenomenological Investigations into Aristotle, is examined to make clear what Heidegger silently assumes in Being and Time. Second, Heideggers adaptation of Husserls use of the term, indication, is outlined to clarify the concept even more. The enhanced understanding of formal indication granted by these two points leads to a better grasp of Heideggers concept of truth, for formal indication and truth are mutually implied for Heidegger. Finally, it is suggested that the reader of Being and Time, on the basis of what formal indication demands, approach the work not as a doctrine to be learned but as a task always requiring further completion.

We must be content, then, in speaking of such subjects and with such premisses to indicate the truth roughly and in outline. Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, 1094b 19211

1. It is by now well known that for Heidegger the main problem with the occidental philosophical tradition is that it has forgotten Being itself and even how to ask about Being. In the sense of the Greeks usage of the word, lethe, forgetfulness is the vice that has bound us to constant misappropriations of the philosophical project. For in our inability or unwillingness to take up the question of Being, we contaminate the project of thinking from the start if we do not clarify what to be means. Thus, getting at the question of Being requires an uncovering and a destruction of those accrued layers of philosophic misappropriation: lethe needs to be deprived of its hegemony. And in this very deprivation, there is the privative a-letheia, the action of getting to the truth of the matter about Being by uncovering what has been forgotten.2

414

RYAN STREETER

Therefore, right at the outset, Heidegger isolates hiddenness as the precondition for his investigation into the meaning of Being, an investigation that must be phenomenological if it is to be ontological (SZ 35). More than that, this phenomenological investigation that goes back to the matter (Sache) of Being itself, in obedience to Husserls battle cry, must also be, as Paul Ricoeur notes, hermeneutical in character. Because the matter of Being has been covered up, phenomenology does not have simple ocular access to it and thus becomes part of the struggle against dissimulation.3 In an attempt to successfully uncover what has been covered up, Heidegger situates himself closer to the original sources of Western thought, approaching ontological clues in a hermeneutic of the logos after the fashion of Aristotles dismantling of the Platonic dialectic (SZ 25). A hermeneutical phenomenology is wary of the solidication of original experiences of factic life into assertions berliefert) as something present-at-hand, such that can be handed down (u that access to those experiences gets blurred or even completely shrouded in obliquity.4 Thus the problem of trying to raise Being to the level of a phenomenon, given that covered-up-ness is the counter-concept to phenomenon (SZ 36): how does one gain access to the question of the meaning of Being without also engaging in the corruption of covering it up, especially since one must put into words and thus irt with the possible corruption that attends the mere recitation of assertions the very investigation that seeks to do the uncovering? Any how-question is a question of method. Heidegger has never been lauded for an explicit and clear usage of method, and rightfully so. For, as his most illustrious pupil, Hans-Georg Gadamer taking cues from Heidegger has evinced, method is contraposed to any successful approach to the truth.5 Nevertheless, Heidegger is acutely aware, on the one hand, that he needs a method at least for a way to structure the approach to his problematic but, on the other hand, that his project requires, in the very employment of method, that our eyes not be diverted away from our fundamental topic to methodical conclusions in short, that we do not cover up what we are trying to uncover. He developed a method to suit this dual complexity. This method has a name: formal indication (formale Anzeige). In coming to terms with Heideggers use of formal indication (Section II), we shall see its relation to his notion of truth (by way of the assertion) as well as the implications that it conveys to the reader of Being and Time (Section III). 2. In recent American scholarship the notion of formal indication has begun to receive attention, the reason being that it sheds signicant light on just how

A QUESTION OF METHOD IN BEING AND TIME

415

Heidegger was proceeding in Being and Time and what he expected the book to accomplish.6 Interest in Heideggers development throughout the 1920s has stemmed largely from the awareness that the hastiness of the composition of Being and Time resulted in certain conceptual and methodological gaps. This awareness has required familiarity with Heideggers lecture courses in order to ll in the gaps.7 One such gap is Heideggers usage of formal indication without ever explaining what it is. This problem is not helped by the fact that the English translators of Sein und Zeit have obscured the infrequent appearances of formale Anzeige and its variants by translating it inconsistently. In the laborious effort to say Being in its immediacy, Heidegger begins by clarifying the Being of that being for whom Being is a matter of importance at all, human being: Dasein, Being-here/there. Beginning this project on the correct footing is of utmost importance (SZ 43). And it is the formal indication of Dasein that is to get us started properly, by approaching the matter of human Being-in-the-world in a philosophically appropriate way. The western tradition has, according to Heidegger, been plagued by the tendency to characterize human Being as a thing instead of a modality, and has become too preoccupied with what a human is at the expense of focusing upon how a human is. Heidegger thus characterizes Descartes, who is the paradigmatic culprit of this tendency, as having become lost in the analysis of the cogito while forgetting to consider the sum, the I am, namely the Being of the human. It is the task of formal indication to point to (an-zeigen) the direction we should follow in our taking up the question of what it means to be. Heideggers broadest formulation of how Dasein is to be characterized is to say that Dasein is that very being that goes about (geht. . .um) its Being in such a way that it comports itself understandingly towards that Being (SZ 53) and has a relationship towards that Being (SZ 12): its Being is an issue for it.8 By this, he is indicating [anzeigen] the formal concept of existence,9 and he tells us at the beginning of x12 that that is what he was doing back in x9. Two fundamental features emerge as important in indicating human Being in this way, namely as a being who is in the mode of going about its very own Being, care-fully comported to that Being. First, because the emphasis is not on what a human is in terms of substances or particles or mere mental acts, but on the way that a human gets around in life, the essence of being human is to be found in human existence (Existenz). Thus, for perhaps the rst time in the western tradition, existence can be said to precede essence (SZ 42, 53). Second, and perhaps not a point as popularized as the existence-maxim,10 this Being around which and toward which Dasein comports itself is in each case mine (ibid). This latter point, in-each-case-mineness (Jemeinigkeit), becomes increasingly important as we move through the analytic of Dasein,

416

RYAN STREETER

because not only is it the precondition for whether or not we are authentic (another well-known discussion), but also because it employs the personal pronoun, thus taking forms like I am, you are, we are (SZ 4243, 53). There is a uniqueness and context-dependent character to the indication of Dasein much like Husserls use of essentially occasional expressions, to which we shall return below. For now it is important to see that this latter part of the second feature (the contextually-signicant aspect of Jemeinigkeit) belongs essentially with the former part (Jemeinigkeit as precondition of Being-authentic/inauthentic) of the second feature and with the rst feature (existence as preceding essence). Reading Being and Time without grasping this essential notion leads to a misappropriation of the content of the book, for without understanding the implications of this indexical nature of the formal indication, Being and Time can easily become thematized into a manual for existential action, which it was not supposed to be. Thus, the following examination of formal indication will emphasize this aspect. In a disposition remarkably close to Aristotles exhortation to move from what is clearer to us to what is clearer in itself, Heideggers project in Being and Time is to move from our common but mistaken grasp of what Dasein is to grasping it ontologically (SZ 15, 43).11 It could be said that Dasein is too close to us, and for this reason we cannot see it enough to grasp it in an original way. We must come back to ourselves by laying bare the basic structures by which we are in each case every day. For instance, we tend to think that self-understanding is relatively complete if we have a comprehensive conceptual delineation of human, but the radicality of Dasein that is sketched in this return to its ontological foundations lies in its ever-incompleteness, its projection onto possibilities that it is not-yet. It is this aspect of Dasein that is difcult to grasp. It can therefore only be comprehended in a formal way. Dasein cannot be presented thematically like other objects with which we cross paths in our daily experience. We must therefore be vigilant in our attempt to present it in the right way, which must be a way that accounts for this incompleteness of Dasein (SZ 43). Heidegger makes this point in the context of just having laid down the two general features of formal indication stated above, and it is no doubt the formal indication of existence that must account for Daseins incompleteness without completing Dasein once and for all. In short, the formal indication is itself marked by this incompleteness, and it must remain incomplete. We learn at the beginning of Division Two that existence formally indicates the Being of Dasein as understanding potentiality-for-Being (SZ 231). Dasein is essentially incomplete, for it always nds itself in a context in which it seeks possibilities for itself, and never does it have all its possibilities fullled such that it can rest comfortably in them and thus cease to project. This

A QUESTION OF METHOD IN BEING AND TIME

417

much can be indicated, but no more, precisely for the same reason as Daseins incompleteness: any formally indicating Dasein (in this case, Heidegger) can never hope to correctly and comprehensively project all of what needs to be projected in any investigation so as to settle an issue once and for all, the issue here being the constitution of that which each of us in each case is. That is why Heidegger claims at the outset in x25 that he is only formally indicating Daseins ontologically constitutive state (SZ 114), and that in considering the I in order to establish the who of Dasein, he is employing a non-binding formal indicator that is general enough to account for various forms of Ihood, even when the I has lost itself (SZ 116). Later, he reiterates what he has formally indicated so as to tempt one to try the t and see if the existentials in Being and Time do not at least point one in a direction that he or she can take up in an existential way that completes them (SZ 313).12 What existence is can only be said in certain ways that call for interpretation: the explication of existence in formally indicative (formalanzeigend) terms is the putting into words for the rst time that Being which we are and are always trying to interpret, namely Dasein. Accordingly, we must decide on the basis of the Being that we nd ourselves to be whether or not that interpretation fruitfully renders that Being (SZ 314315). Any attempt to secure a foundation outside the circle of understanding itself springs from within the circle, for each such attempt to set forth something whether it is a worldless I, life, or a theoretical subject is an interpretive response to factic experience, even if it does not show itself clearly within that experience (SZ 315316).13 The employment of formal indication in Being and Time is sparse. But from the foregoing discussion, what emerges is that it is a matter of starting points, not ending points, and that those starting points point at a direction to be taken.14 The direction indicated must be done in an empty and most general way. This direction, following from the character of the method, is incomplete, wanting completion in a concrete context although there is not enough in this direction itself to satisfy that want. That want must be satised by those who appropriate the text in an existential way. Such an appropriation will serve not only to ll in what is wanting but will also serve to conrm or disconrm the path that Being and Time has sketched out. It is to this end that the text ends: by questioning his own way of having sketched out an analytic of Dasein, Heidegger concludes that one may only decide as to the fruitfulness of this way after having gone along it. In fact, he does not really conclude anything, for he states that the entire text has been nothing other than an attempt to stir up the question of Being anew, and such a stirring has served only as a point of departure and is far from the destination (SZ 437).15

418

RYAN STREETER

However, lest we think that these reections on incompletion are nothing other than wistful intimations of an approaching deconstructionism that emphasizes the impossibility of closure, Heideggers nal words in Being and Time are consistent with that method that was borne out of genuine philosophical concerns and problems that occupied him in the years prior to the publication of the work, most notably in the Winter Semester course of 19211922, which is an introduction to phenomenological research and method.16 The central concern of the lecture course is how to properly gain access to the object of philosophical inquiry. The reason it is of central concern is because of the variety of problems within which we ensnare ourselves when we begin to try to deal with objects. Moving in a disciplined phenomenological vein, Heidegger states that the object of philosophy, like all objects, has a specic mode of access. It is precisely the mode that must be of moment in any philosophical inquiry. For the naive assumption that we can merely start running with clear and distinct objects is the source of a host of philosophical perversions: beginning our thought there is beginning to think too late. Thus our central concern must not be with objects per se but with how they come to be had (Gehabtwerden) how we have them that is, how we hold them in our grasp in advance (PIA 18).17 What he calls having (Haben) is the unthematic mode in which we entertain objects of our thought and of our doings. Thus, by attempting to make it a philosophical object, we are concerning ourselves with the Being-what-how (Was-Wie-Sein) of any object that we hold, grasp, conceive (ibid). Theodore Kisiel calls having the assumption of the conditions that structure the decision to philosophize: having the situation of understanding and the passion for questioning, to begin with.18 This having is of monumental importance, for how we hold objects in a pre-reective way whether they are concrete objects that we use everyday or abstract objects employed in thinking through, say, mathematical problems will determine in large part onto which shore our boat arrives at the end of the investigation of whatever object is in question. Philosophy must try to have the how-it-has/holds. Such a task, namely the analysis of the how of the apprehension of an object rather than the what of the object itself, is difcult. In such an analysis, we do not have any concrete objects that give us content from which we can universalize and form general conclusions. Any such investigation, however helpful in the study of natural objects, will always fall short of its aims in the study of the being of philosophical thinking. It is, therefore, the task of philosophy to do what other disciplines preoccupied, as it were, with the thingness of the objects of their research cannot do, namely to take up the object of its investigation by enacting it so as to come to comprehend it more fully. Philosophy is not a thing or object (Sache), but

A QUESTION OF METHOD IN BEING AND TIME

419

rather a situation, a Habenssituation (PIA 19). This having-situation must be indicated (anzeigend, PIA 1920). What results from Heideggers forming of the philosophical approach in this indicative manner is twofold: rst, the exploration into the character of its object does not look into the content of that which is in question, and yet it yields something determinate and positive (PIA 20, 33); second, as an analysis of the how of the having, it is not just enough to analyze this modality at a distance. This having must be taken up in a comportment without which the questioning could not take place: philosophy is an ongoing philosophizing (PIA 43, 52). What does it mean to say that formal indication does not recognize content and yet does recognize a positive yield on the object under consideration? Any content that comes to the fore in a philosophical investigation must not be heeded as central. What is more important is the way that gets pointed out and the point from which one begins. In the direction given, there is the potentiality for the fulllment of that direction. For this reason Heidegger says that having is indeterminately bound with respect to content but is determinately bound with respect to fulllment (PIA 1920).19 Philosophy must take the path it sketches out for itself in its effort to make itself the object of itself. No content can be securely delivered up for speculation, and thus no object can be held in its grasp in an authentic or complete way, but the object of philosophy can be genuinely indicated. Any denitive content that gets presented in this indication must itself be understood as indicated (PIA 32). The direction given by the direction of approach (Ansatzrichtung) is a denite one, and by being situated in it, I savor to the full and fulll (auskosten und erf ullen) the inauthentic indication by coming to the authentic fulllment that only the way indicated can give.20 In such a savoring and fulllment, that which is indicated is set off from its background (PIA 33). In this giving of a denite direction, there is more than just a lack of content; there is also a positive yield in this formality and attendant emptiness because every formal indication leads to the concrete. The more radical the understanding of that which is empty as formal, the richer it becomes, because it is such that it leads into the concrete (PIA 33). As denite, completion will follow, and thus this indication is not of a static universal that maintains its dignity as a classicatory genus, but of a way that always must be completed if it is to be a way at all. Also, the formal of formal indication is more than just the opposite of material and the equivalent to the eidetic. In its leading to the concrete, the formal gives the approach-character [Ansatzcharakter] of the enactment of the temporalization [Zeitigung] of the original fulllment of that which is indicated (ibid.). Formal indication is certain in its direction and sure to lead directly into the concrete experience of that to which it points, if one follows its cue. Gadamer summarizes well the positive yield of this

420

RYAN STREETER

method: The formal indication points us in the direction in which we are to look. We must learn to say what shows up there and learn to say it in our own words. For only our own words, not repetitions of someone elses, awaken in us the vision of the thing that we ourselves were trying to say.21 The second resulting aspect of Heideggers formulation of formal indication, following in large part from the rst formulation, is that philosophy must be a kind of comportment. Reading philosophy and then repeating deep thoughts learned during that reading, or getting caught up in metaphysical arguments that are sufciently logical but have forgotten whatever it was they set out to understand, or formulating theories based on an inadequate grasp of the Being of that about which one theorizes each of these several instances fails to get at the object of philosophy in the original way that Heidegger sees as vital. He stresses that the logic of the comprehension of the object must be created out of the mode in which the object originally becomes accessible (PIA 20). Philosophical ponticating never fails to miss out on what is phenomenologically most important: getting at the thing itself, which can only be accomplished by nding the most original way to the object. Philosophy is (formally indicated) a comportment (PIA 53). Comportment is not just random behaving or acting, but rather is always a comporting of oneself to . . . (sich verhalten zu . . .), in keeping with Husserls fundamental thesis of intentionality, namely that all consciousness is consciousness of something (PIA 52).22 Heidegger is here radicalizing this a step further by isolating four senses of this comportment to . . . (PIA 53). In being comported to . . ., one is situated in a sense of relation (Bezugssinn), which gives the unique way that one comports oneself to something. There is also a sense in which the content becomes important (Gehaltssinn), in that something is held by the one who comports; but one is also held by that something because one must interpret an object out of its full sense, which is the phenomenon.23 A third sense is that of enactment or actualization (Vollzugsinn), that sense of fulllment, in which, as remarked above, one savors to the full the object as it stands out in the shapeliness of its contours from its background. A nal sense, not found in previous course texts, is a temporalizing sense (Zeitigungssinn) that embraces the how of the entire movement to fulllment or enactment.24 It captures the way in which the fulllment process temporalizes itself (wie er sich zeitigt)25 out of factical life and existence, the situation, and the preconceptions one holds (PIA 53). A temporal process structures any comportment to . . ., embracing the other three senses, and in its general, middle-voiced sense it lingers between the time of the soul and the time of the world, to borrow Ricoeurs terms.26 These two resultant aspects of Heideggers development of formal indication, namely that it yields something positive i.e., a rm direction in

A QUESTION OF METHOD IN BEING AND TIME

421

its empty indicating and that it is a denite comporting to something, leave the philosopher in the position of needing to do more than mere theorizing: philosophical indicating (which is the only way to get at the philosophical object, namely, Being) is radically incomplete, and if it is to be completed, it must be done by the one for whom the indicating is done. Philosophy has as its object, through the analysis of having and comporting to . . ., an understanding comportment to beings as they are in their Being. Thus, in order to have this object in its original accessibility, philosophy must become a fundamental way of life a way that retrieves the fundamental experiences of comportment to objects of all sorts so as to guard against falling into the irresponsible repetition of statements not undergirded by the experiences that gave rise to them (PIA 58, 80). Formal indication leads to what Daniel Dahlstrom calls a reversing-transforming function, which is the transformation of the individual who philosophizes through the original calling of oneself into question in the rigorous push to uncover what it is that one is.27 Thus, formal indication is a process of gaining clarity, but not in a way satisfactory to those who wish to gain a total grasp on the content in question. Its logic is not like that of strict deduction or induction, but rather perhaps nds an analogy in the logic of Aristotles second kind of persuasion, that of putting the audience in the right frame of mind, but less forcibly so.28 Heidegger has aroused through indication a specic realm closest to our immediate Being-here/there, but that realm remains an empty construct until the reader comes to know it in a re-freshing way. Philosophizing in terms of formal indication is intimately related to Heideggers conception of truth, to which I will draw attention below. But in order to come to the question of truth appropriately equipped, we shall briey examine the role of the assertion, which by the very demand of writing has to be what Heidegger employs (like any writer) to formally indicate, and yet which runs the risk of blinding readers to the truth. Before examining these matters, however, it is helpful to briey consider the extent of the Husserlian inuence on Heidegger with respect to what Husserl called essentially occasional expressions, because Husserls formulation of the character of these expressions holds signicance for Heideggers development of his stance with regard to assertions, formal indications, and even truth. 3. Heidegger held seminars in the early twenties on Husserls First Investigation, Expression and Meaning, from which he gleaned the term indication (Anzeige).29 In the third chapter of this First Investigation, Husserl concerns himself with essentially occasional expressions, which are different from

422

RYAN STREETER

objective expressions, the latter referring to those expressions upon which theories can be built and which do not depend on any particular circumstance for their meaning. Occasional (okkasionell) expressions, however, constitute a conceptually unied group of expressions that require an orientation of their meanings to the speakers situation and the occasion (Gelegenheit) in which they are uttered.30 These expressions take several forms: they occur as pronouns (I am, you are), demonstratives (this, that), and what analytical philosophy generally terms indexicals (here, now, above, tomorrow, etc.) (LU 8790, x26, First Investigation). One can grant an objective and universal meaning to such expressions, but whenever they are used, they cannot fully be understood unless we look to the occasion of their utterance. Thus, when a speaker says I. . ., the hearer gathers what that speaker means only by looking to that speaker and the situation in which the speaker says, I. . . To be sure, the use of I has a universal function, namely pointing out [Anzeichen] whatever speaker is designating himself, but in its use it can only serve as an indication (Anzeige) (LU 87, 88, x26, First Investigation). Whenever I use this indication, my hearers do not understand a universal semantic denition of I but understand me to be taking myself as my immediate object. Thus the word I has no power in itself, as does the word, say, lion, whose objective meaning is xed in its utterance. I is only xed with respect to the context of its utterance (LU 88, x26, First Investigation). In the use of occasional expressions, then, there are actually two meanings to each expression: there is the indicating (anzeigend) meaning and the indicated (angezeigt) meaning, the former employed to draw one to the latter, in which the intuitive fulllment of what is indicated occurs. In saying I, the speaker draws the hearer to his or her unique situation (LU 88-89, x26, First Investigation).31 Occasional expressions are essentially ambiguous in that they incompletely express the speakers meaning and can imply an indexical character without using the indexical expression: one may say, There is cake (Es gibt Kuchen), or It is raining (Es regnet), and yet be saying nothing about the nature of cake or rain in general; rather one means that cake is being served right here and now, or that it is currently raining here and now (LU 92, x27, First Investigation). In the Sixth Investigation, Husserl revisits the notion of indication as exercised in occasional expressions, clarifying the reasons as to why these expressions are ambiguous. The ambiguity stems from the fact that the sequence of indication is not the same for the speaker and the hearer. In saying this or I, the speaker knows in advance what is being indicated. But for the hearer, the situation is different, for in the absence of whatever is being pointed to, he or she has access only to a general thought. A full and authentic meaning

A QUESTION OF METHOD IN BEING AND TIME

423

comes to be only when a presentation is added (LU 556557, x5, Sixth Investigation). This makes sense at the level of presenting a tangible object (e.g., this paper), but what about at the conceptual level? The same applies, but there must be an actual re-establishment or recovery (Wiederherstellung) of a past thought that fullls the indication, which is also the empty intention in the form of an occasional expression. Thus the goal of all occasional-expressive discourse is not the general indicating meaning, but the intuitive fulllment in the indicated meaning (LU 557, 558, x5, Sixth Investigation). Two basic factors in Husserls use of indication are notably present in Heideggers use of the same. First, the indicating meaning (formal indication) is pointless if it does not direct one to a fulllment of what it says. In this way the indicating meaning, strong in its direction but unable in itself to fulll itself, depends on the fulllment to truly have meaning. Second, the hearer (reader) occupies the role of the re-enacter, the one upon whom fulllment depends if there is to be fulllment at all. In Being and Time, Heidegger betrays a denite Husserlian streak when he says, The word I is to be understood only in the sense of a non-committal formal indicator (SZ 116). The best way to understand this assertion is to cast it in Heideggers familiar terms: an assertion is a derivative mode of understanding (SZ x33). Understanding is equiprimordially with disposition (Bendlichkeit) and talk (Rede)32 a fundamental mode of Being-inthe-world, and it is characterized by its future-directedness, which it makes manifest as Dasein constantly projects possibilities for itself (SZ 145, 160). This is a pretheoretical aspect of Daseins Being and is something that each of us in each case is doing. This projecting involves two important aspects that involve our present purpose. First, Daseins basic preoccupations are in the mode of possibility, not actuality, for it is constantly stretched out into what it can-be (Seink onnen) but is not yet. In this way, understanding involves disclosedness, which is the laying-open of what is possible for Dasein. To disclose is to bring forth possibilities as a whole into the open from what is otherwise not seen as possible (SZ 144145; cf. 75). A second aspect is that understanding involves meaning, and meaning is said to be had by Dasein when, according to its presuppositional framework, Dasein projects toward and upon something and makes it understandable (verst andlich) as something (SZ 151). We are not here concerned with the correctness of the projection but rather how meaning happens in each case. Understanding is the unthematic ordering of a framework within which certain things get comprehended, and then they are taken as something: with all understanding, interpretation follows (SZ x32). The assertion, then, articulates this interpretation. In articulating it, the assertion points out something, makes something denite, and communicates

424

RYAN STREETER

something, each of these three features deriving from our pretheoretical presuppositional framework that consists of having, seeing, and conceiving in a certain way in advance (SZ 154155; 157). Thus the assertion is existentially grounded in Being-in-the-world. However, because of its derivative character it becomes subjected to abuse, and this is because with the assertion, it becomes all too easy to bring our projection onto possibilities to a halt, so to speak. Although Dasein is always projecting, in its use of the assertion it can cover over the two basic aspects of projecting highlighted above: in capturing a subject matter by pointing it out, making it denite, and communicating it, that subject matter can be taken to mean something present-at-hand and can be passed along like a tangible object. Thus the original as of an interpretation of a pretheoretic understanding gets lost because what was an interpretation gets hypostatized into a mere what. With this move from the sense of meaning as directional and contextual to meaning something present, the projection into a totality of possibilities also gets obscured or lost, and the assertion then loses the disclosiveness of the original understanding and interpretation (SZ 158).33 Talking (Rede) is a fundamental mode of disclosiveness, but if the assertion merely gets passed along without regard for what has been originally disclosed in it, then one cannot be said to truly understand the assertion (SZ 161, 224). For this reason, the assertion is, as John Caputo has remarked, dangerous.34 So how does one truly understand the assertion of Heideggers that the use of I is a non-committal formal indicator? The obvious answer, which Heidegger himself gives, is: by grasping it in the fullness of the totality of possible signications that it discloses (SZ 116). The assertions that Heidegger must employ in formally indicating his topic follow the same rules as all assertions. It seems that the attempt to disclose the totality of implications out of which his assertions indicating human existence emerge is subject to constant misappropriation, and thus getting to the truth of the matter regarding Dasein is doomed to fail. However, Heidegger does not say that every employment of an assertion automatically damns to hopelessness the possibility of coming to the truth through language. In fact, the role of the assertion is given a central role in coming to truth. But, whereas the western tradition has made the assertion the locus of truth (SZ 154), for Heidegger truth becomes the locus of the assertion, which means that one traverses via the assertion into the realm of the original disclosedness where a phenomenon comes to light in its truth. Das Aussagen ist ein Sein zum seienden Ding selbst (SZ 218). Truth, in the sense of the Greek aletheia, is rst and foremost the uncoveredness of something brought out of the dark its disclosure of it as it is. The assertion plays a central role in this moment of uncovering. Dasein expresses itself about

A QUESTION OF METHOD IN BEING AND TIME

425

entities in the form of an assertion, and the entities uncovered by Dasein in its understanding interpretation get pointed out (SZ 218, 220). The function the assertion serves is to show the how, or mode of Being, of the entities that it points out (SZ 224). If we, along with the tradition, become preoccupied with the Being-uncovered aspect of the assertion, then we only see the subject matter as it shows itself in the assertion and perhaps in the context (text at hand, conversation at hand) in which it is used. But if, against the tradition, we focus on the Being-uncovering aspect of the assertion, we become acquainted with the more primordial realm in which the subject matter was rst experienced and brought forth in the disclosedness of a multiplicity of possibilities (SZ 220). Without the retrievability of the rich experience that Being-uncovering indicates, the Being-uncovered will not be grasped as it truly is. Truth is what must be wrested from entities (SZ 222). We are not interested in showing entities merely from some restricted viewpoint. We want to see them as they are. In other words the aletheuein must be distinguished from the apophainesthai. Just because an assertion points out something does not guarantee its truth, for even false assertions point this way. An entitys showing itself as it is in itself is an entitys showing the how of its uncoveredness (SZ 219). This requires, as Ernst Tugendhat argues, more than the assertions merely pointing out the givenness of some entity, more than just bringing something at hand out of concealment to unconcealment. There is also the direction the assertion provides that takes us from the subject matter to its self-manifestation.35 That is, assertions concern more than objects we nd in their immediate givenness, in that they concern the subject matter of whatever the assertion is drawing our attention to. The assertion directs us from the subject matter to the self-manifestation of that subject matter in the space opened up by the assertion. Tugendhat calls this the functional-apophantic character of the assertion. It is unique because it not only gives us insight into a conclusive assertion but also to the one that bears a truth-relation and leads along the way to truth.36 What, then, is the relation between the formal indication and truth? Formally indicative assertions are functional-apophantic assertions in Tugendhats sense, because they point the way to truth without making conclusive their claims about truth. In the movement from the subject matter to its selfmanifestation, formally indicative assertions can only start the movement that must be fullled by the one for whom the assertions are made. The distinction that Heidegger makes between Being-uncovering and Being-uncovered plays a central role here (SZ 220). The Being-uncovered performed by the assertion corresponds to the indicating meaning in Husserls sense: in an assertion our attention is drawn to whatever is expressed. But only when, by

426

RYAN STREETER

looking to that (context, totality of implications) from which the assertion arose and seeing the subject matter in its how, can we get a grasp of it as it is and thus experience it as the indicated meaning. In Heideggers terms, we grasp the subject matter in its Being-uncovering, the original mode in which something is disclosed as something, which in this case is as it is. In the Wiederherstellung to use another of Husserls terms of that mode of Being-uncovering, there is the primordial experience of truth. All that has been said until now has given rather solid clues to the manner in which one is to read Being and Time, but we are now in a position to give those clues some solidity. The implications for reading Being and Time are such that they make the work much more modest in its task than some have taken it to be. Because Heideggers method is formal indication and not metaphysical theorization understood as the attempt to give a comprehensive account of the basic attributes of a human being, it is an empty book. This, of course, sounds odd given the immensity and technicalities of the work itself, but given the method Heidegger is employing, the work cannot be much more than, analogously speaking, an empty intention awaiting intuitive fulllment. In encouraging the appropriation of the matter of the text through formal indication, Heidegger is operating on the basis of a kind of wager. This wager, as I see it, depends upon two presuppositions. The rst one is that we must presuppose truth, understood as the disclosedness of Dasein, in anything we do. Truth, in turn, makes possible any presupposing at all, and it cannot be proved. Insofar as we are beings that uncover matters, we are in such a way that not believing that there is truth makes living impossible (SZ 227229). The second presupposition is that of temporality and its basis for repetition. It is repetition that brings one to remember what one has forgotten: the fundamental character of ones own existence in which one operates every day with an ontic familiarity while remaining ontologically distant (SZ 339, 385386). On the basis of these two presuppositions, Heidegger wagers that his readers will accept the urge given by his analysis to take up the formally indicating concepts and appropriate them in their basic experience. As human beings, they will presuppose with Heidegger that there is something basic to be uncovered, and they will through his analysis come to see what they have-been in such a way that the re-appropriation of past possibilities and accomplishments will yield conrmation of the structures he has outlined. Husserls Wiederherstellung of a past thought becomes temporalized such that in each re-appropriation of something that I have been, something new happens that discloses a matter in its Being in a way more unique than the bare retrieval of something past (cf. SZ 386).

A QUESTION OF METHOD IN BEING AND TIME

427

It might be objected here that it does not make any sense to say that on the basis of certain structures in Heideggers analysis (e.g., truth and temporality/repetition) one will come to see the analysis as yielding something positive, for it is precisely those structures that are in question. But, Heidegger might respond, that is just what a wager is. The wager bets that some one will assume the same presuppositions in order to try out the subsequent claims. For someone to reject, say, Heideggers analysis of truth and temporality, one must be able to give another account that does not presuppose what he has said; and Heidegger is wagering that that will be difcult, if not impossible. Even though Heidegger may be wagering that one will nd his analysis compelling, he can only remain modest with respect to what his project in Being and Time can accomplish. Formal indication can only point and exhort others to carry out the direction in which it points.37 This is what Heidegger meant when he said that all statements about Dasein have a formally indicative character and that they at rst mean something present-at-hand . . . but they indicate the possible understanding of the structures of Dasein and the possible conceptualizing of them that is accessible in such an understanding.38 Thus the present-at-hand meanings (content) of what has been said in Being and Time must be read and considered with respect to the possibilities they open up, and such possibilities can really only be opened up if they are left enough formal space.39 Hence the method of formal indication. It serves to enkindle an interest in the question of Being and yet lends clarity to the lack of philosophical hubris in the line near the end of the text: One must seek a way of casting light on the fundamental question of ontology, and this is the way one must go. Whether this is the only way or even the right one at all, can be decided only after one has gone along it (SZ 437). Notes

1. Ross translation in The Basic Works of Aristotle. ed. Richard McKeon. New York: Random House, 1941. Such subjects is referring to those of political nature, those having to do with action in interpersonal contexts. 2. The forgotten status of the question is introduced by the written frontispiece on page one of Sein und Zeit (Halle: Niemeyer, 1927. 7th ed., 1953 [hereafter SZ]), and it is taken up immediately at the beginning in 1, pp. 24 References to the English edition are to Being and Time, trans. John Macquarrie, Edward Robinson. San Francisco: Harper and Row, 1962. 3. Paul Ricoeur. Time and Narrative. vol. 3., trans. Blamey, Kathleen and David Pellauer. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988. p. 62. 4. I am referring here largely to Heideggers treatment of the assertion in 33, which I will examine more closely below. 5. As best evidenced by the disjunctive role of the and in the title of Gadamers Truth and Method, his magnum opus. 6. For extensive treatment, see Theodore Kisiel. The Genesis of Heideggers Being and Time. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993 (GH). Formal indication appears frequently

428

RYAN STREETER

7. 8.

9. 10. 11. 12.

13. 14.

15.

16.

17.

18. 19.

as a topic in several essays in Theodore Kisiel and John van Buren, eds. Reading Heidegger from he Start: Essays in his Earliest Thought. Albany: SUNY Press, 1994 (RHS). John van Buren makes frequent reference to formal indication in his The Young Heidegger: Rumor of the Hidden King. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994 (YH). See also Daniel Dahlstrom. Das Logische Vorurteil. Vienna: Passagen Verlag, 1994 (LV). For two helpful article-length treatments, see Theodore Kisiels The Genetic Difference in Reading Being and Time. American Catholic Philosophical Quarterly. v. 64, no. 2, 1995. pp. 171187 (GD), and Daniel Dahlstroms Heideggers Method: Philosophical Concepts as Formal Indications. Review of Metaphysics. 47. June, 1994. pp. 775797 (HM). German scholars seem to have been familiar with the signicance of formal indication from the beginning. For instance, see Otto P oggelers Der Denkweg Martin Heideggers. 3rd ed., Pf ullingen: Neske Verlag, 1990, esp. chap. 10 (DMH), and his Heideggers Logische Untersuchungen in Martin Heidegger: Innen- und Auenansichten. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1989 (HLU); and see, Hans-Georg Gadamers Heideggers Ways. trans. John Stanley. Albany: SUNY Press, 1994 (HW). Heidegger composed Sein und Zeit in one month, March 1926, under as Kisiel puts it publish or perish conditions (GD 184, 185). Even though Macquarrie and Robinson rightly translate umgehen as is an issue for, it is important not to lose the sense that comes with the German verb, viz. a sense of modality and activity, not just a sense of thoughtful reection. Note the related usage of Umgang at SZ 6667. Macquarrie and Robinson have calling attention to for anzeigen. Famous largely because of Sartres popularization of the thesis See LEtre et le n eant. Paris: Gallimard, 1943. p. 61 and Lexistentialisme est un humanisme. Paris, 1946. p. 17. See Aristotles Physics, 184a 1718. The beginning of the paragraph in question would be better rendered in the English edition as The formal indication of the idea of existence was guided. . . . Die formale Anzeige der Existenzidee war geleitet. . . Implicit in these claims seems to be a critique of Descartes, Dilthey (and perhaps Nietzsche and even Bergson), and Kant, respectively. John van Buren makes this point: Formal indication . . . indicates or points to what is still absent in die Sache selbst, what is still to be thought and is on the way to language (YH 42). Van Buren has shown how this theme of the need for others to take up the question of Being in their own way continues into the later Heidegger and was of constant concern for him, as evidenced by his exhortation to his seminar students: There will be no heideggerizing here! We want to get at the topic (YH 45). Ph anomenologische Interpretationen zu Aristoteles: Einf uhrung in die Ph anomenologische Forschung. volume 61 (PIA) in the Gesamtausgabe. Despite the title, the lecture course has little to do with Aristotle but is perhaps one of Heideggers best treatments of the nature of phenomenology and its way of approaching philosophical problematics. Any translations from this text are my own. It should be noted that volume 60 of Heideggers Gesamtausgabe, that of the Winter Semester 19201921, has recently appeared, in which Heidegger also treats the notion of formal indication at length. I will not, however, treat that text in this essay. Heidegger is speaking generally here of what becomes well-known in Being and Time as fore-having (Vorhabe), fore-seeing (Vorsicht), and fore-grasping/-conceiving (Vorgriff). The present lecture course helps to understand these latter terms more fully, because Heidegger treats here much more comprehensively and thematically what he gives minimal attention to in Being and Time. See SZ 150151. Kisiel, GH 233234. With respect to fulllment refers here to vollzugshaft: the idea is that the direction always leads to an enactment of the way indicated, an idea to which I will turn below.

A QUESTION OF METHOD IN BEING AND TIME

429

20. Heidegger has eigentlich and uneigentlich for what I have termed authentic and inauthentic. It might be better to translate these terms as actual and non-actual, for the point at hand here has more to do with the non-actuality of what is indicated and the actuality of its fulllment, following the Husserlian schema of intentionality. 21. Hans-Georg Gadamer. Martin Heideggers One Way, trans. P. Christopher Smith, in RHS, 33. Otto P oggeler makes a similar point when he says that formal indication points one to the happening of truth but not to its concrete fulllment; it has a provocative character with the tendency to awaken (DMH 272). 22. See the Logische Untersuchungen, V.2. 13; and the Ideen, II.2. 36. 23. Kisiel notes that this containment sense is formally broad enough to include all realms of activity and passivity, from those realms in which we have meaningful objects to those realms in which the objects seem to have us in their grasp, as in addictions and preoccupations (GH 234). 24. Kisiel, ibid, states that Heidegger had already developed the three basic senses of intentionality in the War Emergency Semester of 1919, and that the temporalizing sense is added here in the Winter Semester of 192122. 25. Contained in sich zeitigen is the sense of becoming ripe, of coming to fruition, as wine grapes come of season. 26. Ricocur, p. 14, does use more technical terms for these phenomena, namely psychological and cosmological time. 27. See PIA 153, 168169. Dahlstrom, HM 782790, treats well this function as well as the referring-prohibiting function of formal indication, both of which serve to reinforce the incompleteness of formal indication and its offer to the philosopher to take up the question of Being in fresh and new ways. For related remarks by Heidegger, see his, Die Grundbegriffe der Metaphysik: Welt, Endlichkeit, Einsamkeit. Winter Semester 1929-30, volumes 29/30 in the Gesamtausgabe, pp. 428430. 28. Aristotle relies not only on the speakers character and the content of a speech itself in persuasion but also on the speakers ability to arouse the right frame of mind in the audience by understanding how to bring about certain emotions at the right time (Rhetoric, 1356a 1ff.). 29. Van Buren, YH 328; 406n.5. Van Buren notes that a student of Heideggers, G unther Stern, took up Heideggers reading of Husserls use of indication in a dissertation, which thus provides some documentation for this Husserl-Heidegger relation. 30. Edmund Husserl. Logische Untersuchungen vv XIX/I and XIX/2 The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1984 (LU) p. 87 26, First Investigation. 31. For a treatment of meaning indications in occasional expressions, see Aaron Gurwitsch. Outlines of a Theory of Essentially Occasional Expressions, in Readings on Edmund Husserls Logical Investigations. ed J.N. Mohanty The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1977 pp. 112127. 32. Macquarrie and Robinsons state-of-mind and discourse, respectively. 33. This process is what Jean Grondin calls the propositional fallout of an existential relationship to the world whereby the proposition levels everything to the language of the given (S is P). Gadamer and Augustine: On the Origin of the Hermeneutical Claim to Universality, in Hermeneutics and Truth, ed. Brice Wachterhauser, Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1994. p. 140. 34. For an insightful treatment of the notion of the assertion, see Caputos Radical Hermeneutics, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984. especially pp. 7376. 35. Ernst Tugendhat. Heideggers Idea of Truth, in Hermeneutics and Truth, p. 87. 36. Ibid., pp. 9192. 37. Kisiel captures this exhortational aspect well: [Formal] indications, like life itself, are never nal, are always tentative and provisional. As intrinsically shifting distributive universals, they ultimately perform a hortatory function in philosophy, exhorting each individual to assume the orienting comportment suggested by such non-generic universals that call for a proximating re-turn to the ineffable immediacy of our being, in order to

430

RYAN STREETER

intensify the inexhaustible sense of the immediate in which we already and always nd ourselves. (GD 186). 38. Logik Die Frage nach der Wahrheit in Gesamtausgabe, volume 21, WS 192526. p. 410. 39. As an example of the possibilities that can be opened up by such a method, one might consider the ways to which Heideggers way of proceeding has given rise to, in a sense, the three Heideggers: the existentialist Heidegger found in the work of Sartre, the hermeneutical Heidegger found in the work of Gadamer, and the deconstructionist Heidegger found in the work of Derrida.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Dreyfus The Primacy of Phenomenology Over Logical AnalysisDokument38 SeitenDreyfus The Primacy of Phenomenology Over Logical Analysisassnapkin4100% (1)

- Hegel's Recollection: A Study of Image in The Phenomenology of SpiritDokument11 SeitenHegel's Recollection: A Study of Image in The Phenomenology of Spiritdanielschwartz88Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cover LetterDokument7 SeitenCover Letterrohan guptaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Logic of Schelling's Freedom EssayDokument10 SeitenThe Logic of Schelling's Freedom EssayrcarturoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hegel on Self-Consciousness: Desire and Death in the Phenomenology of SpiritVon EverandHegel on Self-Consciousness: Desire and Death in the Phenomenology of SpiritBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (6)

- Schurmann and Singularity GranelDokument14 SeitenSchurmann and Singularity GranelmangsilvaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Meaning: From Parmenides To Wittgenstein: Philosophy As "Footnotes To Parmenides"Dokument21 SeitenMeaning: From Parmenides To Wittgenstein: Philosophy As "Footnotes To Parmenides"luu linhNoch keine Bewertungen

- 15 Husserl - The Marginal Notes On Being and TimeDokument74 Seiten15 Husserl - The Marginal Notes On Being and TimeAleksandra Veljkovic100% (1)

- THE AND: Fixed Stars Constellations AstrologyDokument258 SeitenTHE AND: Fixed Stars Constellations AstrologyВукашин Б Васић100% (1)

- Meister Eckhart Mystic and PhilosopherDokument3 SeitenMeister Eckhart Mystic and PhilosopherFandungaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rudolf Carnap - The Logical Structure of The World - Pseudoproblems in Philosophy-University of California Press (1969)Dokument391 SeitenRudolf Carnap - The Logical Structure of The World - Pseudoproblems in Philosophy-University of California Press (1969)Domingos Ernesto da Silva100% (1)

- Between Hermeneutics and SemioticsDokument18 SeitenBetween Hermeneutics and SemioticsIsrael ChávezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Derrida, Jacques - Joyce, James - Mahon, Peter - Imagining Joyce and Derrida - Between Finnegans Wake and Glas (2007, University of Toronto Press)Dokument416 SeitenDerrida, Jacques - Joyce, James - Mahon, Peter - Imagining Joyce and Derrida - Between Finnegans Wake and Glas (2007, University of Toronto Press)GeorgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brentano's Concept of Intentional Inexistence and the Division in Approaches to IntentionalityDokument22 SeitenBrentano's Concept of Intentional Inexistence and the Division in Approaches to IntentionalityJuan SolernóNoch keine Bewertungen

- 01 Arthur O. Lovejoy - The Meaning of Romanticism For The Historian of Ideas +Dokument23 Seiten01 Arthur O. Lovejoy - The Meaning of Romanticism For The Historian of Ideas +Hana CurcicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Martin Heidegger - Identity and DifferenceDokument78 SeitenMartin Heidegger - Identity and DifferenceOneirmos100% (1)

- Taminiaux - The Platonic Roots of Heidegger's Political Thought PDFDokument19 SeitenTaminiaux - The Platonic Roots of Heidegger's Political Thought PDFSardanapal ben EsarhaddonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Georg Wilhelm Friedrich HEGEL Lectures On The PHILOSOPHY of RELIGION Volume 1 E.B.speirs and J.burdon Sanderson London 1895Dokument370 SeitenGeorg Wilhelm Friedrich HEGEL Lectures On The PHILOSOPHY of RELIGION Volume 1 E.B.speirs and J.burdon Sanderson London 1895francis batt100% (1)

- Kant and the Capacity to Judge: Sensibility and Discursivity in the Transcendental Analytic of the Critique of Pure ReasonVon EverandKant and the Capacity to Judge: Sensibility and Discursivity in the Transcendental Analytic of the Critique of Pure ReasonBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (4)

- Hopkins Poetry and PhilosophyDokument8 SeitenHopkins Poetry and Philosophygerard.casey2051Noch keine Bewertungen

- Dorion Cairns (Auth.) Guide For Translating Husserl 1973Dokument159 SeitenDorion Cairns (Auth.) Guide For Translating Husserl 1973Filippo Nobili100% (1)

- Exercises in Structural DynamicsDokument13 SeitenExercises in Structural DynamicsObinna ObiefuleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Althusser and Fanon's theories of ideological interpellationDokument12 SeitenAlthusser and Fanon's theories of ideological interpellationsocphilNoch keine Bewertungen

- ADORNO en Subject and ObjectDokument8 SeitenADORNO en Subject and ObjectlectordigitalisNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3.4 - Schürmann, Reiner - Adventures of The Double Negation. On Richard Bernstein's Call For Anti-Anti-Humanism (EN)Dokument10 Seiten3.4 - Schürmann, Reiner - Adventures of The Double Negation. On Richard Bernstein's Call For Anti-Anti-Humanism (EN)Johann Vessant RoigNoch keine Bewertungen

- Being, Essence and Substance in Plato and Aristotle: Reviews: Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews: University of Notre DameDokument7 SeitenBeing, Essence and Substance in Plato and Aristotle: Reviews: Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews: University of Notre DameGarland HaneyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Treasury of Philosophy: Runes, Dagobert D. (Dagobert David), 1902-1982, Ed: Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming: Internet ArchiveDokument15 SeitenTreasury of Philosophy: Runes, Dagobert D. (Dagobert David), 1902-1982, Ed: Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming: Internet ArchiveMarinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scrum: The Agile Framework for Complex WorkDokument29 SeitenScrum: The Agile Framework for Complex WorksaikrishnatadiboyinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Michael Inwood A Heidegger Dictionary 3Dokument299 SeitenMichael Inwood A Heidegger Dictionary 3Aboubakr SoleimanpourNoch keine Bewertungen

- Förster, E. - The Twenty-Five Years of Philosophy. A Systematic Reconstruction (Harvard University Press, 2012)Dokument425 SeitenFörster, E. - The Twenty-Five Years of Philosophy. A Systematic Reconstruction (Harvard University Press, 2012)entronatorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Back To KantDokument23 SeitenBack To KantMarcos PhilipeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Francoise Dastur - Phenomenology of EventDokument13 SeitenFrancoise Dastur - Phenomenology of Eventkobarna100% (1)

- Exploring the Relationship Between Neo-Kantianism and Phenomenology in Early 20th Century German PhilosophyDokument17 SeitenExploring the Relationship Between Neo-Kantianism and Phenomenology in Early 20th Century German PhilosophyAngela Dean100% (1)

- Aron Gurwitsch-A Non-Egological Conception of Consciousness PDFDokument15 SeitenAron Gurwitsch-A Non-Egological Conception of Consciousness PDFJuan Pablo CotrinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brady Bowman - HegelsTransitiontoSelfconsciousnessinthePhenomenologyDokument17 SeitenBrady Bowman - HegelsTransitiontoSelfconsciousnessinthePhenomenologyCristián Ignacio0% (1)

- Kisiel Heidegger PDFDokument42 SeitenKisiel Heidegger PDFweltfremdheit100% (1)

- Transplanting the Metaphysical Organ: German Romanticism between Leibniz and MarxVon EverandTransplanting the Metaphysical Organ: German Romanticism between Leibniz and MarxNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cassirer's Unpublished Critique of Heidegger (J. Krois)Dokument14 SeitenCassirer's Unpublished Critique of Heidegger (J. Krois)Angela Dean0% (1)

- The Later Schelling On Philosophical Religion and ChristianityDokument24 SeitenThe Later Schelling On Philosophical Religion and Christianity7 9Noch keine Bewertungen

- 3850 Mathematics Stage 3 Marking Guide Sample 2Dokument1 Seite3850 Mathematics Stage 3 Marking Guide Sample 2AshleeGedeliahNoch keine Bewertungen

- WETZ, F. The Phenomenological Anthropology of Hans BlumenbergDokument26 SeitenWETZ, F. The Phenomenological Anthropology of Hans BlumenbergalbertolecarosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Heideggers Hermeneutik der Faktizität: L'herméneutique de la facticité de Heidegger - Heidegger's Hermeneutics of FacticityVon EverandHeideggers Hermeneutik der Faktizität: L'herméneutique de la facticité de Heidegger - Heidegger's Hermeneutics of FacticitySylvain CamilleriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Heidegger Lask FichteDokument32 SeitenHeidegger Lask FichteStefano Smad0% (1)

- Lectures On LogicDokument743 SeitenLectures On LogicHanganu Cornelia100% (2)

- A Parting of The Ways Carnap Cassirer and HeideggeDokument7 SeitenA Parting of The Ways Carnap Cassirer and HeideggeIzzulotrob OsratNoch keine Bewertungen

- Allison, Henry E. - Kant's Theory of TasteDokument442 SeitenAllison, Henry E. - Kant's Theory of TasteSergio MartinsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scheler On. Max Scheler On The Place of Man in The Cosmos (M. Farber, 1954)Dokument8 SeitenScheler On. Max Scheler On The Place of Man in The Cosmos (M. Farber, 1954)coolashakerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Warminski, Andrzej - Reading in Interpretation. Hölderlin, Hegel, HeideggerDokument289 SeitenWarminski, Andrzej - Reading in Interpretation. Hölderlin, Hegel, HeideggerRodrigo Castillo100% (3)

- 02 Sheehan - Introduction - Husserl and Heidegger - The Making and Unmaking of A RelationshipDokument40 Seiten02 Sheehan - Introduction - Husserl and Heidegger - The Making and Unmaking of A RelationshipAleksandra VeljkovicNoch keine Bewertungen

- BRASSIER & MALIK. Reason Is Inconsolable and Non-Conciliatory. InterviewDokument17 SeitenBRASSIER & MALIK. Reason Is Inconsolable and Non-Conciliatory. InterviewErnesto CastroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Between Kant and Hegel - Lectures On German IdealismDokument6 SeitenBetween Kant and Hegel - Lectures On German IdealismSaulo SauloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Burge 2007 Predication and TruthDokument29 SeitenBurge 2007 Predication and TruthBrad MajorsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Heidegger Zum Ereignis-Denken (GA73) An Index PDFDokument338 SeitenHeidegger Zum Ereignis-Denken (GA73) An Index PDFDaniel FerrerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Searle, John - Proper NamesDokument9 SeitenSearle, John - Proper NamesRobert ConwayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Books 401: Rockhurst Jesuit University Curtis L. HancockDokument3 SeitenBooks 401: Rockhurst Jesuit University Curtis L. HancockDuque39Noch keine Bewertungen

- Overcoming Epistemology - TaylorDokument16 SeitenOvercoming Epistemology - Taylorsmac226100% (1)

- Brandom, Robert B. (2002) Tales of The Mighty Dead Historical Essays in The Metaphysics of IntentionalityDokument32 SeitenBrandom, Robert B. (2002) Tales of The Mighty Dead Historical Essays in The Metaphysics of IntentionalityAnonymous 8i3JR3SLtRNoch keine Bewertungen

- The coming Evil? paper explores apocalyptic end timesDokument22 SeitenThe coming Evil? paper explores apocalyptic end timesclaudiomainoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Inheriting the Future: Legacies of Kant, Freud, and FlaubertVon EverandInheriting the Future: Legacies of Kant, Freud, and FlaubertNoch keine Bewertungen

- Of Levinas and Shakespeare: "To See Another Thus"Von EverandOf Levinas and Shakespeare: "To See Another Thus"Moshe GoldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pen Ny Lane, Thereis A Bar Ber Showing Pho To Graphs of Ev 'Ry Head He's Had The Plea Sure To - KnowDokument3 SeitenPen Ny Lane, Thereis A Bar Ber Showing Pho To Graphs of Ev 'Ry Head He's Had The Plea Sure To - KnowjrewingheroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Track 0: Moderate 120Dokument3 SeitenTrack 0: Moderate 120jrewingheroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Baron Suite in CDokument7 SeitenBaron Suite in CjrewingheroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corbetta PreludeDokument1 SeiteCorbetta PreludejrewingheroNoch keine Bewertungen

- AlcanizDokument2 SeitenAlcanizjrewingheroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mathematical Notation DocumentDokument11 SeitenMathematical Notation DocumentjrewingheroNoch keine Bewertungen

- 120 1. Prelude: P - P - TR? TR TR TR? P P TR?Dokument16 Seiten120 1. Prelude: P - P - TR? TR TR TR? P P TR?jrewingheroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Violin 1 1Dokument3 SeitenViolin 1 1jrewingheroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Heidegger's Being and Time Introduction GuideDokument2 SeitenHeidegger's Being and Time Introduction GuidejrewingheroNoch keine Bewertungen

- US Chess PlayersDokument1 SeiteUS Chess PlayersjrewingheroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bach's Violin Sonata No. 1 Fugue Sheet MusicDokument5 SeitenBach's Violin Sonata No. 1 Fugue Sheet MusicjrewingheroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Heidegger Books 2Dokument2 SeitenHeidegger Books 2jrewingheroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Afternoon DelightDokument3 SeitenAfternoon DelightjrewingheroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chess BooksDokument2 SeitenChess Booksjrewinghero0% (1)

- Reading ListDokument2 SeitenReading ListjrewingheroNoch keine Bewertungen

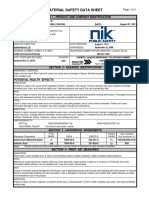

- Nik InstructionsDokument1 SeiteNik InstructionsjrewingheroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Note On Bold Face TypeDokument1 SeiteNote On Bold Face TypejrewingheroNoch keine Bewertungen

- All Objects Have PropertiesDokument1 SeiteAll Objects Have PropertiesjrewingheroNoch keine Bewertungen

- AgendaDokument1 SeiteAgendajrewingheroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anselm On TruthDokument1 SeiteAnselm On TruthjrewingheroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chess IntuitionDokument3 SeitenChess IntuitionjrewingheroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Natural DrugsDokument2 SeitenNatural Drugsjrewinghero100% (1)

- MSDS - Test ADokument4 SeitenMSDS - Test AjrewingheroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bacteria 2Dokument2 SeitenBacteria 2jrewingheroNoch keine Bewertungen

- MSDS - Test WDokument4 SeitenMSDS - Test WjrewingheroNoch keine Bewertungen

- MSDS - Test DDokument4 SeitenMSDS - Test DjrewingheroNoch keine Bewertungen

- EffexorDokument1 SeiteEffexorjrewingheroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Basic Drug CategoriesDokument1 SeiteBasic Drug CategoriesjrewingheroNoch keine Bewertungen

- SubstanceDokument11 SeitenSubstancejrewingheroNoch keine Bewertungen

- RegimenDokument1 SeiteRegimenjrewingheroNoch keine Bewertungen

- MobileMapper Office 4.6.2 - Release NoteDokument5 SeitenMobileMapper Office 4.6.2 - Release NoteNaikiai TsntsakNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2nd Quarterly Exam in Math 7Dokument4 Seiten2nd Quarterly Exam in Math 7LIWLIWA SUGUITANNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cisco Network Services Orchestrator (NSO) Operations (NSO200) v2.0Dokument3 SeitenCisco Network Services Orchestrator (NSO) Operations (NSO200) v2.0parthieeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wormhole: Topological SpacetimeDokument14 SeitenWormhole: Topological SpacetimeHimanshu GiriNoch keine Bewertungen

- BureaucracyDokument19 SeitenBureaucracyJohnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clamdoc PDFDokument55 SeitenClamdoc PDFtranduongtinhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Classical Conditioning Worksheet 1Dokument2 SeitenClassical Conditioning Worksheet 1api-642709499Noch keine Bewertungen

- TSN Connections Tech CatalogDokument84 SeitenTSN Connections Tech CatalogkingdbmNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marketing Theory and PracticeDokument18 SeitenMarketing Theory and PracticeRohit SahniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Famous Scientist Wanted Poster Project 2014Dokument2 SeitenFamous Scientist Wanted Poster Project 2014api-265998805Noch keine Bewertungen

- W5 - Rational and Irrational NumbersDokument2 SeitenW5 - Rational and Irrational Numbersjahnavi poddarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Flourishing ReducedDokument6 SeitenHuman Flourishing ReducedJanine anzanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Print!!Dokument130 SeitenPrint!!Au RiveraNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2.3.4 Design Values of Actions: BS EN 1990: A1.2.2 & NaDokument3 Seiten2.3.4 Design Values of Actions: BS EN 1990: A1.2.2 & NaSrini VasanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strain Index Calculator English UnitsDokument1 SeiteStrain Index Calculator English UnitsFrancisco Vicent PachecoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3rd International Conference On Managing Pavements (1994)Dokument9 Seiten3rd International Conference On Managing Pavements (1994)IkhwannurNoch keine Bewertungen

- Distributed Flow Routing: Venkatesh Merwade, Center For Research in Water ResourcesDokument20 SeitenDistributed Flow Routing: Venkatesh Merwade, Center For Research in Water Resourceszarakkhan masoodNoch keine Bewertungen

- Higher Unit 06b Check in Test Linear Graphs Coordinate GeometryDokument7 SeitenHigher Unit 06b Check in Test Linear Graphs Coordinate GeometryPrishaa DharnidharkaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ZMMR34Dokument25 SeitenZMMR34Himanshu PrasadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ampac Xp95 DetectorDokument4 SeitenAmpac Xp95 DetectortinduongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Matrices PDFDokument13 SeitenMatrices PDFRJ Baluyot MontallaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Horace Mann Record: Delegations Win Best With Model PerformancesDokument8 SeitenThe Horace Mann Record: Delegations Win Best With Model PerformancesJeff BargNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ipcrf - Teacher I - IIIDokument16 SeitenIpcrf - Teacher I - IIIMc Clarens LaguertaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Electrical Apparatus and DevicesDokument19 SeitenElectrical Apparatus and DevicesKian SalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Morton, Donald - Return of The CyberqueerDokument14 SeitenMorton, Donald - Return of The Cyberqueerjen-leeNoch keine Bewertungen