Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Final Research Study Design

Hochgeladen von

api-247669843Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Final Research Study Design

Hochgeladen von

api-247669843Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Running Head: IMPACT OF LIVING LEARNING COMMUNITIES

The Impact of Living-Learning Communities on Student Retention in Residence Halls Christopher J. Van Drimmelen EDUC 500 Instructor: Dr. Christopher Johnson December 4, 2012

IMPACT OF LIVING LEARNING COMMUNITIES INTRODUCTION Problem Statement Colleges and universities constantly face the question how can we better engage our students to increase their success? Residential programs are one answer to this question, however, in recent years these programs have also found themselves in need of re-tooling to meet the needs of the modern student population. Living-learning communities are one way in which colleges and universities strive to keep on-campus residents engaged and successful, both in their academic and personal lives. Living learning communities have enjoyed some success in practice, however research on this topic is generally qualitative, with no experimental studies having been done due to the many factors involved in operating a successful campus housing operation. This study aims to measure the impacts of a living learning community with a higher degree of certainty than has been previously achieved. Literature Review

Residential programs and campus housing departments frequently tout the benefits of living in on-campus housing. Indeed, there is research that suggests that living on campus, particularly in the first year, has positive impacts on students. A recent article featuring a series of case studies in the Review of Higher Education demonstrated a link between higher first to second year retention as a result of on-campus living (Schudde, 2011). At the same time, there is a long-standing trend of rejection of certain types of campus housing among modern students. Generally speaking, students are no longer satisfied with a strictly traditional dormitory arrangement. A study conducted using student input from surveys and focus groups on the type of environment that was desired

IMPACT OF LIVING LEARNING COMMUNITIES

included greater privacy, interaction, safety, a sense of identity, a sense of belonging, and a sense of responsibility for the environment (Striner, 1973). Programs that have been successful in motivating students to remain in on-campus housing often center around providing a physical living space that students find attractive and livable, however this is only part of a broader equation of engagement (Hill, 2004). Living learning communities have been tested at many colleges and universities in the United States. They are characterized by a strong presence of faculty and at least one academic department in the living environment. The goal is to foster significant interaction between students, academic faculty, and the content of academic programs (Schushok & Sriram, 2009). While institutions have attempted (some very successfully) to assess their own individual living learning communities, the research that has been conducted has not been a coordinated effort. Single-institution studies with idiosyncratic research interests have generated some results, which have produced a patchwork of information on the effects of L/L programs on student outcomes. Multi-institutional studies have been absent from research on living learning communities so far (Inkelas et. al., 2006). Research Hypothesis Student participation in a living learning community rather than a traditional residence hall environment will increase engagement and retention. Operational Definitions Living-learning community: a residential community based around an academic program with significant participation from academic faculty in addition to traditional residence-hall staff.

IMPACT OF LIVING LEARNING COMMUNITIES

Traditional residence hall environment: a residential community not based around a theme or academic program. Suite-style residence hall: a residence hall design featuring two-person rooms adjoining a semi-private bathroom shared between two rooms. Resident Director: a live in professional staff member employed by the campus Housing department. Resident Assistant/Resident Advisor: live in paraprofessional student staff employed by the campus Housing department. Faculty In Residence: a faculty member from the academic program that the living learning community is associated with who lives on site in the residence hall. Methodology This study will take advantage of a unique opportunity presented by the construction of new residence halls at two Seattle area Universities. The population to be studied includes all incoming first-year students at Seattle University and the University of Washingtons main Seattle campus who will live on campus for their first year. Two new residence halls are being constructed at each institution that are near-identical in design due to the same architectural firm being hired by both campuses. Students will be sorted into the halls based on a stratified sampling model based on major. Since both universities have significant populations of students majoring in science, math, engineering, and technology (STEM) fields, one of the new halls on each campus will be set up around a STEM living-learning community. The other new hall on each campus will serve as a control. The strata for the purposes of the study will be STEM majors and Non-STEM majors, with each strata comprising 50% of the population of each hall. Students from

IMPACT OF LIVING LEARNING COMMUNITIES within these strata will be randomly selected for placement in the halls. This will also serve as a kind of dual control in that not only will there be a control group of equivalent composition in the treatment and the control hall on each campus, but the results of the STEM and Non-STEM groups can also be cross compared. Stratified sampling was chosen in order to select students who will probably benefit most from a STEM learning community, but also to have an equivalent sized community within the hall that may benefit from the presence of the learning community but not as directly. Bias in this sample may occur, particularly due to differing on-campus housing practices between Seattle University and the University of Washington. Seattle University requires all undergraduates to live on campus for their first year, while the University of Washington does not. This may lead to a sample that is less representative of the student population as a whole at the University of Washington, however since we are primarily interested in those who live on campus, this self-selection bias is not a large concern. Instruments Data for this study will come from the National Survey of Student Engagement and from the Housing department on each campus data on student retention within the residence halls. The National Survey of Student Engagement is a well established annual survey published by the Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research which

measures engagement across the categories of how an institution (a) challenges students academically, (b) fosters active and collaborative learning, (c) encourages student interactions with faculty, (d) provides enriching educational experiences, and (e) maintains a supportive campus environment (Kuh, et. al., n.d.). This test has been in active use since 2000 after pilot testing and design, which was based on 25 years worth of educational

IMPACT OF LIVING LEARNING COMMUNITIES

research. The results are highly consistent and widely seen to be reliable, with Cronbachs alpha coefficients for each category in excess of 0.80. This test is designed for undergraduates across institutional types and based on the assumption that greater engagement equals greater success. While this study will focus on a subset of the undergraduate population, the data from the categories of fosters active and collaborative learning, encourages student interactions with faculty, and maintains a supportive campus environment are particularly salient given the treatment applied. Professionally, this instrument is highly regarded as accurate, valid, and psychometrically sound, thus it is used nationwide and will serve as a good instrument for this study (Kuh et. al., n.d.). Another source of data that this study will use is residence hall retention rates (whether or not students return for a second year in on-campus housing). This is tracked by the housing departments at both campuses. Research Design For the purposes of this study, 624 on-campus students at each university will be assigned to two new residence halls on each campus, one of which will be the treatment hall (STEM living learning community), and the other will serve as the control (non-living learning community, traditional residence hall environment). 50% of the students in each hall will be STEM majors, but assignment between the halls will be otherwise random. The treatment halls on each campus will have an ongoing relationship with their science and engineering programs, while the control halls will not have an ongoing relationship with any academic department. Each treatment hall will have two faculty in residence and will partner between the hall staff and academic faculty to implement

IMPACT OF LIVING LEARNING COMMUNITIES ongoing programming that supports the STEM partnership theme. The control halls will have traditional residence hall programming only. At the end of the academic year, the NSSE survey will be administered to all students who have completed the full year in the hall that they were originally assigned.

Results will be compared between the treatment and control halls on the same campus, and also between the institutions to determine if there is a different impact of a living learning community based on institutional size and type. Retention rates will also be compared based on the number of students who apply to return the following year. Threats to validity in this study include subject attrition (not all students will remain in the hall for the entire year), differences in the experience and training level of the hall staffs, and difference in academic approach between the faculty of the two institutions. Validity will be controlled through random assignment to a hall (attrition levels should be relatively constant across halls if subjects are randomly assigned), selection of hall staff members who have roughly equivalent experience and training, and selection of live in faculty with similar research and teaching interests. Diffusion of treatment may also be an issue given that traditional residence hall programming models do not prohibit and even encourage students to attend programs in other halls. This will be controlled by not advertising living-learning-community activities outside of the treatment halls. The external validity of this study may be limited by geography, local demographics, and institutional type. Given that both of these institutions are in Seattle, Washington, the data may not be equally applicable in all parts of the United States. There is also a question of generalizability to institutional types that are not easily comparable to either Seattle University (low-mid size private) or University of Washington (very-large state research).

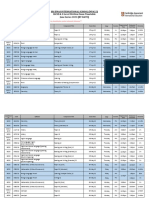

IMPACT OF LIVING LEARNING COMMUNITIES Analysis of Results Statistical analysis will be done using a factorial ANOVA to compare data across the two institutions treatment and control halls like so: STEM Students SU Treatment Hall SU Control Hall UW Treatment Hall UW Control Hall Sample Data Active & Collaborative Learning SU Treatment SU Control UW Treatment UW Control Student-Faculty Interaction SU Treatment SU Control UW Treatment UW Control Supportive Campus Environment SU Treatment SU Control UW Treatment UW Control Return Rates SU Treatment SU Control UW Treatment N 302 299 307 300 N 302 299 307 300 N 302 299 307 300 Mean 50 45 54 45 Mean 46 35 47 35 Mean 64 63 64 63 SD 12 16 13 16 SD 12 18 12 18 SD 17 18 17 18 SEM 0.10 0.12 0.10 0.12 SEM 0.10 0.15 0.10 0.15 SEM 0.10 0.15 0.10 0.16 Non-STEM Students

% Students Returning to Hall 9% 2% 11%

IMPACT OF LIVING LEARNING COMMUNITIES UW Control Conclusions and Implications of Results After conducting this experiment, significant increases in student engagement and 1%

retention were found in the halls in which living-learning communities were implemented. The research hypothesis of this study was supported in that the presence of a living learning community did result in higher NSSE scores in the categories of active & collaborative learning, student-faculty interaction, and supportive campus environment, in addition to higher retention rates in both treatment halls. The final category, supportive campus environment, did increase, though not significantly enough to conclusively state that the living-learning communities had a direct impact on the results. This may suggest that other factors are more important in the results for this category than for the other two sampled. While significant increases in student engagement were found at these two institutions, this study may still have limited generalizability. Specifically, only two institutions were studied, both in the same geographic area. This may cause bias in the type of students who participated as well as the institutional culture. Additionally, no small or specialized institutions were included in this study, so further work may need to be done to determine if living learning communities are as effective at these types of institutions. While the results of this dual-institution study show promise in favor of the effect of living learning communities, practitioners should be careful not to declare them to be the best tool to increase on-campus engagement in all cases on the basis of this study alone.

IMPACT OF LIVING LEARNING COMMUNITIES

10

References Hill, C. (2004). Housing strategies for the 21st century: Revitalizing residential life on campus. Planning For Higher Education, 32(3), 25-36. Inkelas, K., Vogt, K. E., Longerbeam, S. D., Owen, J., & Johnson, D. (2006). Measuring outcomes of living-learning programs: Examining college environments and student learning and development. JGE: The Journal Of General Education, 55(1), 40-76. Kuh, G. D., Hayek, J. C., Carini, R. M., Oimet, J. A., Gonyea, R. M., & Kennedy, J. (n.d). National Survey of Student Engagement. Schudde, L. T. (2011). The causal effect of campus residency on college student retention. Review Of Higher Education, 34(4), 581-610. Shushok, F., & Sriram, R. (2009). Exploring the effect of a residential academic affairsstudent affairs partnership: The first year of an engineering and computer science living-learning center. Journal Of College & University Student Housing, 36(2), 68-81. Striner, E. B., Society for Coll. and Univ. Planning, N. Y., & Educational Facilities Labs., I. Y. (1973). College Housing and Community Design. Planning for Higher

Education.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Areas For GrowthDokument6 SeitenAreas For Growthapi-247669843Noch keine Bewertungen

- Chris LetterDokument2 SeitenChris Letterapi-247669843Noch keine Bewertungen

- Conference 1 Page ProposalDokument1 SeiteConference 1 Page Proposalapi-247669843Noch keine Bewertungen

- Chris Sdad 584 Final PaperDokument8 SeitenChris Sdad 584 Final Paperapi-247669843Noch keine Bewertungen

- Leadership Philosophy FinalDokument15 SeitenLeadership Philosophy Finalapi-247669843Noch keine Bewertungen

- Chris Artifact HDokument11 SeitenChris Artifact Hapi-247669843Noch keine Bewertungen

- C Van Drimmelen ResumeDokument2 SeitenC Van Drimmelen Resumeapi-247669843Noch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Educational Comics and Educational Cartoons As Teaching Material in The Social Studies CourseDokument11 SeitenEducational Comics and Educational Cartoons As Teaching Material in The Social Studies CourseTestNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mogadishu University Prospectus 2012Dokument56 SeitenMogadishu University Prospectus 2012Dr. Abdurahman M. Abdullahi ( baadiyow)100% (2)

- Bus 172Dokument17 SeitenBus 172souravsamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Glossary of Maharishi Effect TermsDokument2 SeitenGlossary of Maharishi Effect TermsCarrissaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Split 299918433489071391Dokument5 SeitenSplit 299918433489071391vidyakumari808940Noch keine Bewertungen

- How To Write A Nursing Research Literature ReviewDokument4 SeitenHow To Write A Nursing Research Literature Reviewfvet7q93Noch keine Bewertungen

- BSccourse2009 10Dokument465 SeitenBSccourse2009 10Keith LauNoch keine Bewertungen

- GT Reading Test 1Dokument12 SeitenGT Reading Test 1juana7724100% (1)

- This Study Resource Was: Summary of The Magician's Twin: CS Lewis and The Case Against ScientismDokument3 SeitenThis Study Resource Was: Summary of The Magician's Twin: CS Lewis and The Case Against ScientismJuanito AbenojarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Risk MatrixDokument8 SeitenRisk MatrixAlexNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Role of Sensory Evaluation in The Food IndustryDokument9 SeitenThe Role of Sensory Evaluation in The Food IndustryAnahii KampanithaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Written Exam Timetable June Series 2022 by Date 1Dokument8 SeitenWritten Exam Timetable June Series 2022 by Date 1MIKS AmpangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Academic Calendar Course Offer Regi Guidelines Regi Schedule Tentative Exam Routine 2024 Merged 2c539d9cb3Dokument10 SeitenAcademic Calendar Course Offer Regi Guidelines Regi Schedule Tentative Exam Routine 2024 Merged 2c539d9cb3moslahuddin2022Noch keine Bewertungen

- Group 1 - The Meanings and The Scope of PsycholinguisticsDokument20 SeitenGroup 1 - The Meanings and The Scope of PsycholinguisticsLaila Nur Hanifah laila7586fbs.2019Noch keine Bewertungen

- Decision Making Under Risk Continued: Bayes'Theorem and Posterior ProbabilitiesDokument21 SeitenDecision Making Under Risk Continued: Bayes'Theorem and Posterior ProbabilitiesmariushNoch keine Bewertungen

- DP EE - Interdisciplinary Approach-8-18Dokument11 SeitenDP EE - Interdisciplinary Approach-8-18Android 18Noch keine Bewertungen

- SOCIOLOGY STRATEGY - Rank 63, Tanai Sultania, CSE - 2016 - INSIGHTS PDFDokument4 SeitenSOCIOLOGY STRATEGY - Rank 63, Tanai Sultania, CSE - 2016 - INSIGHTS PDFmaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Flourishing ReducedDokument6 SeitenHuman Flourishing ReducedJanine anzanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Table of Specification DiassDokument2 SeitenTable of Specification DiassChris John GaraldaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson Plan Class 6 CH Magnet Day 3Dokument8 SeitenLesson Plan Class 6 CH Magnet Day 3Ujjwal Kr. Sinha100% (1)

- Performance Performance of Agricultural CooperativesDokument103 SeitenPerformance Performance of Agricultural CooperativesRammee AnuwerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mcom RM MCQ2021PDF PDFDokument17 SeitenMcom RM MCQ2021PDF PDFtheva ganeshini mNoch keine Bewertungen

- Week 007 The Research ParadigmsDokument12 SeitenWeek 007 The Research ParadigmsMae ChannNoch keine Bewertungen

- Daily Instructional Lesson Plan: Worcester County Public SchoolsDokument6 SeitenDaily Instructional Lesson Plan: Worcester County Public Schoolsapi-309747527Noch keine Bewertungen

- Announcement - Listening Test - SampleDokument21 SeitenAnnouncement - Listening Test - SampleThe Special ThingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Science, Religion and Communism in Cold War Europe: Edited by Paul Betts Stephen A. SmithDokument310 SeitenScience, Religion and Communism in Cold War Europe: Edited by Paul Betts Stephen A. SmithPatrickNoch keine Bewertungen

- VLS PFE 1 Measurement Activity Sheet 1Dokument3 SeitenVLS PFE 1 Measurement Activity Sheet 1Lance De GuzmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- New ?TRB PG Assistant Original Question Papers Collection 2001-2022 TamilaruviDokument7 SeitenNew ?TRB PG Assistant Original Question Papers Collection 2001-2022 TamilaruvitamilaruviwebNoch keine Bewertungen

- HhfyDokument21 SeitenHhfyWinard PalcatNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is CL-NLP-1Dokument12 SeitenWhat Is CL-NLP-1Parinay SethNoch keine Bewertungen