Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Project Proposal

Hochgeladen von

api-251641757Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Project Proposal

Hochgeladen von

api-251641757Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

! ! !

MID-AGE ADULT PROGRAM

VECOVA

CLEMENT LI October 18, 2013 (Recent Revision: Nov 14, 2013)

! ! !

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: Vecova has previously identified youth transitioning into adulthood and aging clients are a priority for programs and services. That being said, exposure to stressors at various points along the life course has long-term consequences for well-being (Lupien, McEwen, Gnunar & Heim, 2009, pg.1; Gotlib & Wheaton, 1997, pg.30). Persons with developmental disabilities (DD) aged 25-45 should not be excluded from the development of programs and services as DD affects every individual differently at various stages of life. The ability to offer programming for a continuous age spectrum also allows for the monitoring and mitigation of aging effects. In addition, because our health care system functions on treating diseases, only a small minority of resources are allocated towards non-acute or sub-acute wellness (AHS, 2013). By emphasizing the role of the client as the central determinant (Sterling, Silke, Tucker, Fricks, Druss, 2010; pg. 1), society is capable of completing the World Health Organizations (1948) definition of health that states: physical, mental, and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmary. The disability community has a somewhat younger perception of an aged person. Because of premature aging experienced by some disability groups and sparse numbers of very old groups, this label is generally applied to people who are 55 years and over (Bigby, 2002; pg. 5). Thus, the aging process can begin much earlier for persons with DD and mid-age implications may have greater effects on old age than expected. For an individual to self-assess their wellbeing they must be aware of the indicators such as optimism and self-esteem (Helliwell and Putnam, 2004; pg.1). A large and growing literature suggests that physical health is conditioned by social factors and dictated by an individuals optimism and self-esteem. The frequency of social support that correlates to social wellbeing have been noted to have cognitive and physiological benefits such as lower stress hormones and lower risk of dementia (Seeman, Lusignolo, Albert, and Berkman, 2001; pg.2). Additionally, optimistic and socially well individuals are more likely to make healthy choices such as taking vitamins on a regular basis (Scheier and Carver, 1992; pg.13).

"

! ! !

Social roles provide identity and meaning to life, and often a persons social status is influenced by the different social roles he/she has within the community. Persons with DD are often been ostracized, hidden, and considered unequal because of how others view them (Sheets, 2005; pg.2), and are considered vulnerable because of their difficulty in exercising choice and restricted social networks (Bigby, 2002; pg.2). When people with disabilities have the opportunity to fulfil positive social roles in their communities, attitudes towards disability can change. There are many different ways in which people with disabilities can be supported to achieve valued social roles. Assisting people with disabilities to improve their skills and abilities, promoting positive images of people with disabilities in the community, and working to change negative attitudes are all helpful (WHO, 2010, pg. 3). Therefore, a program to target social wellbeing for adults with developmental disabilities should be considered. Since nutrition has been recognized as an important component of healthy aging with one of the main characteristics of frailty defined as loss of muscle and total body mass (Topinkova, 2008; pg.4), it is important to educate mid-age adults on healthy meals and diets. A social program that considers food preparation could help address this gap from various angles. The program would combine educational components of healthy eating and balanced meals in a leisure setting around a round table of peers. This will help to address social isolation that persons with DD experience by providing them with access to an informal social setting with peers. Objectives of this program will be for participants to build new friendships and take part in otherwise rare social settings. Contents of the program must be taught to encourage personal practice, inclusion with all individuals, and safety precautions. For the program to be sustainable it is essential for aspects of education or asset building to be blended into leisure based application. Program agenda will be quite informal, and drop in attendance would be tolerated. Program Challenges: 1.) Program will be created for new demographic for which there are few resources, contacts, connections, networks for, and may result in initial low turnout. Address: Set up a focus group for individuals in the target age to identify their needs.

!

! ! !

2.) Limited research in this population group. Address: May signify the existing neglect and lack of attention given to these individuals. 3.) To sustain engaging environment, program structure and components must combine educational (may be less interactive) component and socialization/leisure component. 4.) Social component as key focus, but should not neglect to Mental and Physical wellbeing. Address: Adopt proven and working models from programs such as Club45. 5.) Program activities must be age-appropriate, interactive and encourages independence, but still considerably safe and inclusive. Address: Focus group should provide useful data needed to plan for activities. Product of environmental scan: 1.) Go Group (Autism Calgary): For 18-35 who have Aspergers Syndrome and are PDD ineligible. This group meets weekly to participate, as a group, in the community at large. 2.) Golden Age Club Bronze Age 35-44: adult day programs, $15/year membership. Activities include: darts, gentle yoga, bingo, movie day, etc., educationa; computer classes, walking program. 3.) Beau Vita West: a day program for adults with developmental and intellectual disabilities that promotes living full, responsible, and productive lives. Individuals are inspired to initiate and act upon personal choices in a supportive setting, to build a unique schedule of activities, and to acquire skills that will be useful in their daily lives at home, at work, and in their communities. Program options include skills for daily living, selfexpression, recreation and leisure, community experiences, communication and socialization. 4.) Center for possibilities (Hobart, Indiana): Providing programming for students age 22 and above with a developmental disability focusing on the development of self-care skills, daily living skills and academic advancement 5.) Rising Star Studios: offers various art, music, dance, computer, photography, exercise and life skill classes for teens and adults with Autism Spectrum Disorders or other communication challenges. 6.) Visionaries & Voices: is a studio/gallery created specifically for artists with disabilities to grow both personally and professionally.

!

! ! !

7.) Potential place: members develop relationships with staff and fellow members. The programs has what is called Work-Ordered days which provide structure day-to-day activities to promote confidence, self-esteem and the development of friendships, provides employment opportunities ie: transitional employment, educational opportunities to ensure each member has the skills and ability to complete their education.

References: AHS. (2013). Alberta Health 2013/2014 Funding Allocation. Accessed from Alberta Health website: http://www.health.alberta.ca/documents/Chart-Funding-Allocation-13-14.pdf Bigby, C. (2002). Ageing people with a lifelong disability: challenges for the aged care and disability sectors. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 27(4), 231-241. Brown, G. W., & Harris, T. O. (1978). Social origins of depression. New York: Free Press. Chan, J.M., Lang, r., Rispoli, M., OReilly, M., Sigafoos, J. & Cole, H. (2009). Use of peermediated interventions in the treatment of autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3, 876-889. Fried, L.P., Carlson, M.C., Freedman, M., Frick, K.D., Glass, T.A., Hill, J., McGill, S., Rebok, G.W., Seeman, T., Tielsch, J., Wasik, B.A., & Zeger, S., (2004). A social model for health promotion for an aging population: initial evidence of the Experience Corps Model. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 81(1), 64-78. Garcia-Villamisar, D.A. & Dattilo, J. (2010). Effects of a leisure programme on quality of life and stress of individuals with ASD. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 54(7), 611-619. Go Group. Information retrieved from Autism Calgary website: http://www.autismcalgary.com/about/programs-and-services/#sthash.8jrGv3N3.dpuf Gotlib, I. H., & Wheaton, B. (Eds.). (1997). Stress and adversity over the life course: Trajectories and turning points. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Helliwell, J. F., & Putnam, R. D. (2004). The social context of well-being. Philosophical transactions-royal society of London series B biological sciences, 1435-1446.

! ! !

Lupien, S. J., McEwen, B. S., Gunnar, M. R., & Heim, C. (2009). Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(6), 434445. ODay, B. (2009). Project SEARCH: opening door toe mployment for young people with disabilities. Mathematica Policy Research Inc., 09(06), 1-4. Reichow, B. & Volkmar, F.R. (2010). Social skills interventions for individuals with Autism: evaluation for evidence-based practices within a best evidence synthesis framework. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 149-166. Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (1992). Effects of optimism on psychological and physical wellbeing: Theoretical overview and empirical update. Cognitive therapy and research, 16(2), 201-228. Seeman, T. E., Lusignolo, T. M., Albert, M., & Berkman, L. (2001). Social relationships, social support, and patterns of cognitive aging in healthy, high-functioning older adults: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Health psychology, 20(4), 243. Sheets, D. J. (2005). Aging with disabilities: ageism and more. Generations, 29(3), 37-41. Sterling, E. W., Silke, A., Tucker, S., Fricks, L., & Druss, B. G. (2010). Integrating wellness, recovery, and self-management for mental health consumers. Community mental health journal, 46(2), 130-138. Topinkov, E. (2008). Aging, disability and frailty. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism, 52(Suppl. 1), 6-11. Van Laarhoven, T. & Van Laarhoven-Myers, T. (2006). Comparison of three video-based instructional procedures for teaching daily living skills to persons with developmental disabilities. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 41(4), 365-381. World Health Organization. (1948). Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization as

adopted by the International Health Conference, New York, 19-22 June, 1946; signed on 22 July 1946 by the representatives of 61 States (Official Records of the World Health Organization, no. 2, p. 100) and entered into force on 7 April 1948. Accessed:

http://www.who.int/about/definition/en/print.html World Health Organization. (2010). Social Component, Community-Based Rehabilitation: CBR Guidelines. Accessed: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241548052_social_eng.pdf

&

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Clement Li - Aging and Emerging Technologies PaperDokument16 SeitenClement Li - Aging and Emerging Technologies Paperapi-251641757Noch keine Bewertungen

- Drblashewicz ReferenceDokument2 SeitenDrblashewicz Referenceapi-251641757Noch keine Bewertungen

- Clement Li - Autism Spectrum Disorder Critical Research PaperDokument13 SeitenClement Li - Autism Spectrum Disorder Critical Research Paperapi-251641757Noch keine Bewertungen

- Clement Li - Legal BriefDokument6 SeitenClement Li - Legal Briefapi-251641757Noch keine Bewertungen

- Overview V 2Dokument4 SeitenOverview V 2api-251641757Noch keine Bewertungen

- App Framework V 3Dokument7 SeitenApp Framework V 3api-251641757Noch keine Bewertungen

- Indesign AshxDokument21 SeitenIndesign Ashxapi-251641757Noch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (894)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- History of Special Education in the PhilippinesDokument8 SeitenHistory of Special Education in the PhilippinesAngelica Marin100% (4)

- UCSP Reviewer LawDokument6 SeitenUCSP Reviewer LawEJ RaveloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Triple CDokument2 SeitenTriple CBethany Keily100% (1)

- Assess functional abilities with 17-item scaleDokument5 SeitenAssess functional abilities with 17-item scaleJose Paul RaderNoch keine Bewertungen

- SPED Action Plan of SchoolsDokument2 SeitenSPED Action Plan of SchoolsMarjorie IdianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Samarthanam ProfileDokument12 SeitenSamarthanam ProfilemyndsetsNoch keine Bewertungen

- GiftAbled Holistic Approach 2022Dokument13 SeitenGiftAbled Holistic Approach 2022vinnshineNoch keine Bewertungen

- Binder 3-13141Dokument93 SeitenBinder 3-13141Anubhav JainNoch keine Bewertungen

- MCA Second Year 4 Sem Exam FormDokument67 SeitenMCA Second Year 4 Sem Exam Formvidya patilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Learning Disabilities Association of Ontario Ldao 2Dokument4 SeitenLearning Disabilities Association of Ontario Ldao 2api-366074669Noch keine Bewertungen

- WORKBOOK SUBJECT 7 CHCAGE004 Implement Interventions With Older People at Risk CHCAGE003 Co OrdinatDokument181 SeitenWORKBOOK SUBJECT 7 CHCAGE004 Implement Interventions With Older People at Risk CHCAGE003 Co Ordinatklm klm100% (1)

- BG HealthAndSafetyDokument60 SeitenBG HealthAndSafetyVasile NodisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Expounding The Rehabilitation Service For Acquired Visual Impairment Contingent On Assistive Technology AcceptanceDokument6 SeitenExpounding The Rehabilitation Service For Acquired Visual Impairment Contingent On Assistive Technology AcceptanceNicolas MendezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Classroom Activity CHCDIS003Dokument4 SeitenClassroom Activity CHCDIS003Sonam GurungNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vending Machine LetterDokument1 SeiteVending Machine LetterTarah TaylorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Haverfordwest Tennis Club Membership Form 2018-2019Dokument2 SeitenHaverfordwest Tennis Club Membership Form 2018-2019Gareth RobinsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- I Am SamDokument4 SeitenI Am SamEmJay BalansagNoch keine Bewertungen

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Psy4327.501 06f Taught by Edward Davis (Ecd022000)Dokument5 SeitenUT Dallas Syllabus For Psy4327.501 06f Taught by Edward Davis (Ecd022000)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippians 4 13 - PPT DEFENSEDokument17 SeitenPhilippians 4 13 - PPT DEFENSESherwina Marie del RosarioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case 10 Shutter IslandDokument3 SeitenCase 10 Shutter IslandAnkith ReddyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abnormal Psychology: Clinical Perspectives On Psychological Disorders PDF - Descargar, LeerDokument10 SeitenAbnormal Psychology: Clinical Perspectives On Psychological Disorders PDF - Descargar, Leerroven desuNoch keine Bewertungen

- (B) Evaluate The Characteristics, Types and Measures of Schizophrenia and Psychotic Disorders, Including A Discussion of Case StudiesDokument1 Seite(B) Evaluate The Characteristics, Types and Measures of Schizophrenia and Psychotic Disorders, Including A Discussion of Case StudiesHenry Nguyen PhamNoch keine Bewertungen

- 177 211110 1659555955 Paper 1 06112021 Pam Northern Chapter Webinar ms1184pptxDokument65 Seiten177 211110 1659555955 Paper 1 06112021 Pam Northern Chapter Webinar ms1184pptxFong Wei JunNoch keine Bewertungen

- Williams and Mavin 2012Dokument21 SeitenWilliams and Mavin 2012fionakumaricampbell6631Noch keine Bewertungen

- CAMPBELL, F.K. Exploring Internalized AbleismDokument18 SeitenCAMPBELL, F.K. Exploring Internalized AbleismBruna DomingosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Job Application FormDokument8 SeitenJob Application FormCreative SuccessNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary of Anxiety Disorders (DSM-5)Dokument6 SeitenSummary of Anxiety Disorders (DSM-5)Villamorchard100% (3)

- Abi LympicsDokument24 SeitenAbi LympicsSMNoch keine Bewertungen

- Communication Skills For Children With Severe Learning DifficultiesDokument10 SeitenCommunication Skills For Children With Severe Learning DifficultiesMay Grace E. BalbinNoch keine Bewertungen

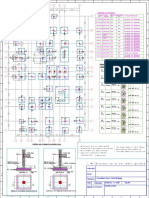

- Column and Footing Plan (22!02!2022) APDokument1 SeiteColumn and Footing Plan (22!02!2022) APRanjit BarmanNoch keine Bewertungen