Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Dutch East Indies - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia

Hochgeladen von

Zk31kjgaiTWOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Dutch East Indies - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia

Hochgeladen von

Zk31kjgaiTWCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

http://en.wikipedia.

org/wiki/Dutch_East_Indies

11/02/2014 11:19

Coordinates: 2.0S 118.0E

Dutch East Indies

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Dutch East Indies (or Netherlands East Indies; Dutch: Nederlands-Oost-Indi;

Indonesian: Hindia-Belanda) was a Dutch colony that became modern Indonesia following

World War II. It was formed from the nationalised colonies of the Dutch East India Company,

which came under the administration of the Dutch government in 1800 until 1950 while

Indonesia declared Independence from the Netherlands to Commemorate the 5th Anniversary

of Independence from Japan as Unrecognised State after United Indonesian States Dissolved.

During the 19th century, Dutch possessions and hegemony were expanded, reaching their

greatest territorial extent in the early 20th century. This colony which later formed modern-day

Indonesia was one of the most valuable European colonies under the Dutch Empire's rule,[2]

and contributed to Dutch global prominence in spice and cash crop trade in the 19th to early

20th century.[3] The colonial social order was based on rigid racial and social structures with a

Dutch elite living separate but linked to their native subjects.[4] The term Indonesia came into

use for the geographical location after 1880. In the early 20th century, local intellectuals began

developing the concept of Indonesia as a nation state, and set the stage for an independence

movement.[5]

Japan's World War II occupation dismantled much of the Dutch colonial state and economy.

Following the Japanese surrender in August 1945, Indonesian nationalists declared

independence which they fought to secure during the subsequent Indonesian National

Revolution. The Netherlands formally recognized Indonesian sovereignty at the 1949 Dutch

Indonesian Round Table Conference as the Autonomous Republic within the Netherlands with

the exception of the Netherlands New Guinea (Western New Guinea), which was ceded to

Indonesia in 1963 under the provisions of the New York Agreement.

Contents

1 Etymology

2 History

2.1 Company rule

2.2 Dutch conquests

2.3 World War II and independence

2.4 Economic history

2.5 Social history

3 Government

3.1 Education

3.2 Law and administration

3.3 Administrative divisions

3.4 Armed forces

4 Culture

4.1 Language and literature

4.2 Visual art

4.3 Theatre and film

4.4 Science

4.5 Cuisine

4.6 Architecture

5 Colonial heritage in the Netherlands

6 See also

7 Notes

8 References

9 Further reading

10 External links

Etymology

The word Indies comes from Latin: Indus. The original name Dutch Indies (Dutch:

Nederlandsch-Indi) was translated by the English as the Dutch East Indies, to keep it distinct

from the Dutch West Indies. The name Dutch Indies is recorded in the Dutch East India

Company's documents of the early 1620s.[6]

Netherlands East Indies

Nederlands-Oost-Indi

Hindia-Belanda

Dutch colony

18001942

19451950a

Flag

Coat of arms

Map of the Dutch East Indies showing its territorial expansion

from 1800 to its fullest extent prior to Japanese occupation in

1942.

Capital

Batavia (now Jakarta)

Languages

Indonesian

Dutch

Indigenous languages

Religion

Sunni Islam

Christianity

Hinduism

Buddhism

Government

Governor-General

- 18001801 (first)

- 1949 (last)

Colonial administration

History

- VOC era

- VOC nationalised

- Japanese occupation[1]

- Independence proclaimed

- Dutch recognition as the

Autonomous Republic

within the Netherlands

- Independence from the

Netherlands after United

Indonesian States

Dissolved

Pieter G. van Overstraten

A. H. J. Lovinka

16031800

1 January 1800

Feb 1942 Aug 1945

17 August 1945

27 December 1949

17 August 1950

Population

- 1930 est.

60,727,233

Currency

Dutch East Indies gulden

Today part of

Indonesia

a. Occupied by Japanese forces between 1942 and 1945, followed

by the Indonesian National Revolution until 1949. Indonesia

proclaimed its independence on 17 August 1945. Netherlands

New Guinea was transferred to Indonesia in 1963.

Scholars writing in English use the terms Indi, the Dutch East Indies, the Netherlands Indies, and colonial Indonesia interchangeably.[7]

History

Company rule

Dutch East Indies - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

1 of 14

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dutch_East_Indies

11/02/2014 11:19

See also: Dutch East India Company in Indonesia and Economic history of the Netherlands (15001815)

Centuries before Europeans arrived, the Indonesian archipelago supported various states including commercially oriented coastal trading states and

inland agrarian states.[8] The first Europeans to arrive were the Portuguese in the late fifteenth century and following disruption of Dutch access to

spices in Europe,[9] the first Dutch expedition set sail for the East Indies in 1595 to access spices directly from Asia. When it made a 400% profit on its

return, other Dutch expeditions soon followed. Recognizing the potential of the East Indies trade, the Dutch government amalgamated the competing

companies into the United East India Company (VOC).[9]

The VOC was granted a charter to wage war, build fortresses, and make treaties across Asia.[9] A capital was established at Batavia (now Jakarta),

which became the centre of the VOC's Asian trading network.[10] To their original monopolies on nutmeg, mace spice, cloves and cinnamon, the

company and later colonial administrations introduced non-indigenous cash crops like coffee, tea, cacao, tobacco, rubber, sugar and opium, and

safeguarded their commercial interests by taking over surrounding territory.[10] Smuggling, the ongoing expense of war, corruption and

mismanagement lead to bankruptcy by the end of the 18th century. The company was formally dissolved in 1800 and its colonial possessions in the

Indonesian archipelago (including much of Java, parts of Sumatra, much of Maluku, and the hinterlands of ports such as Makasar, Manado, and

Kupang) were nationalized under the Dutch Republic as the Dutch East Indies.[11]

Dutch conquests

From the arrival of the first Dutch ships in the late sixteenth century, to the declaration of independence in 1945, Dutch control over the Indonesian

archipelago was always tenuous.[12] Although Java was dominated by the Dutch,[13] many areas remained independent throughout much of this time

including Aceh, Bali, Lombok and Borneo.[12] There were numerous wars and disturbances across the archipelago as various indigenous groups

resisted efforts to establish a Dutch hegemony, which weakened Dutch control and tied up its military forces.[14] Piracy remained a problem until the

mid-19th century.[12] Finally in the early 20th century, imperial dominance was extended across what was to become the territory of modern-day

Indonesia.

In 1806, with the Netherlands under French domination, Napoleon appointed his brother Louis Bonaparte to the

Dutch throne which led to the 1808 appointment of Marshall Herman Willem Daendels to Governor General of

the Dutch East Indies.[15] In 1811, British forces occupied several Dutch East Indies ports including Java and

Thomas Stamford Raffles became Lieutenant Governor. Dutch control was restored in 1816.[16] Under the 1824

Anglo-Dutch Treaty, the Dutch secured British settlements such as Bengkulu in Sumatra, in exchange for

ceding control of their possessions in the Malay Peninsula and Dutch India. The resulting borders between

British and Dutch possessions remain between Malaysia and Indonesia.

Since the establishment of the VOC in the seventeenth century, the expansion of Dutch territory had been a

business matter. Graaf van den Bosch's Governor-generalship (18301835) confirmed profitability as the

foundation of official policy was to restrict its attention to Java, Sumatra and Bangka.[17] However, from about

1840, Dutch national expansionism saw them wage a series of wars to enlarge and consolidate their possessions

in the outer islands.[18] Motivations included: the protection of areas already held; the intervention of Dutch

officials ambitious for glory or promotion; and to establish Dutch claims throughout the archipelago to prevent

intervention from other Western powers during the European push for colonial possessions.[17] As exploitation of Indonesian resources expanded off

Java, most of the outer islands came under direct Dutch government control or influence.

The submission of Prince Diponegoro

to General De Kock at the end of the

Java War in 1830

The Dutch 7th Battalion advancing in

Bali in 1846.

The Dutch subjugated the Minangkabau of Sumatra in the Padri War (182138)[19] and the Java War (182530)

ended significant Javanese resistance.[20] The Banjarmasin War (18591863) in southeast Kalimantan resulted

in the defeat of the Sultan.[21] After failed expeditions to conquer Bali in 1846 and 1848, an 1849 intervention

brought northern Bali under Dutch control. The most prolonged military expedition was the Aceh War in which

a Dutch invasion in 1873 was met with indigenous guerrilla resistance and ended with an Acehnese surrender in

1912.[20] Disturbances continued to break out on both Java and Sumatra during the remainder of the 19th

century,[12] however, the island of Lombok came under Dutch control in 1894,[22] and Batak resistance in

northern Sumatra was quashed in 1895.[20] Towards the end of the nineteenth century, the balance of military

power shifted towards the industrialising Dutch and against pre-industrial independent Indonesian states as the

technology gap widened.[17] Military leaders and Dutch politicians said they had a moral duty to free the

Indonesian peoples from indigenous rulers who were oppressive, backward, or did not respect international

law.[23]

Although Indonesian rebellions broke out, direct colonial rule was extended throughout the rest of the archipelago from 1901 to 1910 and control taken

from the remaining independent local rulers.[24] Southwestern Sulawesi was occupied in 190506, the island of Bali was subjugated with military

conquests in 1906 and 1908, as were the remaining independent kingdoms in Maluku, Sumatra, Kalimantan, and Nusa Tenggara.[20][23] Other rulers

including the Sultans of Tidore in Maluku, Pontianak (Kalimantan), and Palembang in Sumatra, requested Dutch protection from independent

neighbours thereby avoiding Dutch military conquest and were able to negotiate better conditions under colonial rule.[23] The Bird's Head Peninsula

(Western New Guinea), was brought under Dutch administration in 1920. This final territorial range would form the territory of the Republic of

Indonesia.

World War II and independence

Main articles: Dutch East Indies Campaign, Japanese occupation of Indonesia, and Indonesian National Revolution

On 10 January 1942, during the Dutch East Indies Campaign, Japanese forces invaded the Dutch East Indies as part of the Pacific War.[25] The rubber

plantations and oil fields of the Dutch East Indies were considered crucial for the Japanese war effort.[citation needed] Allied forces were quickly

overwhelmed by the Japanese and on 8 March 1942 the Royal Dutch East Indies Army surrendered in Java.[26][27]

Dutch East Indies - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

2 of 14

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dutch_East_Indies

Fuelled by the Japanese Light of Asia war propaganda[28] and the Indonesian National Awakening, a vast

majority of the indigenous Dutch East Indies population first welcomed the Japanese as liberators from the

colonial Dutch empire, but this sentiment quickly changed as the occupation turned out to be far more

oppressive and ruinous than the Dutch colonial government.[29][30] The Japanese occupation during World War

II brought about the fall of the colonial state in Indonesia,[31] as the Japanese removed as much of the Dutch

government structure as they could, replacing it with their own regime.[32] Although the top positions were held

by the Japanese, the internment of all Dutch citizens meant that Indonesians filled many leadership and

administrative positions. In contrast to Dutch repression of Indonesian nationalism, the Japanese allowed

indigenous leaders to forge links amongst the masses, and they trained and armed the younger generations.[33]

11/02/2014 11:19

Tjarda van Starkenborgh Stachouwer

and B.C. de Jonge, the last and

second-to-last Governor-General of

the Dutch East Indies before Japanese

invasion.

According to a UN report, four million people died in Indonesia as a result of the Japanese occupation.[34]

Following the Japanese surrender in August 1945, nationalist leaders Sukarno and Mohammad Hatta declared

Indonesian independence. A four and a half-year struggle followed as the Dutch tried to re-establish their

colony; although Dutch forces re-occupied most of Indonesia's territory a guerilla struggle ensued, and the

majority of Indonesians, and ultimately international opinion, favoured Indonesian independence. In December

1949, the Netherlands formally recognised Indonesian sovereignty with the exception of the Netherlands New Guinea (Western New Guinea).

Sukarno's government campaigned for Indonesian control of the territory, and with pressure from the United States, the Netherlands agreed to the New

York Agreement which ceded the territory to Indonesian administration in May 1963.

Economic history

See also: Cultivation System and Liberal Period (Dutch East Indies)

The economic history of the colony was closely related to the economic health of the mother country.[35]

Despite increasing returns from the Dutch system of land tax, Dutch finances had been severely affected by the

cost of the Java War and the Padri War, and the Dutch loss of Belgium in 1830 brought the Netherlands to the

brink of bankruptcy. In 1830, a new Governor-General, Johannes van den Bosch, was appointed to make the

Indies pay their way through Dutch exploitation of its resources. With the Dutch achieving political domination

throughout Java for the first time in 1830,[36] it was possible to introduce an agricultural policy of governmentcontrolled forced cultivation. Termed cultuurstelsel (cultivation system) in Dutch and tanam paksa (forced

plantation) in Indonesian, farmers were required to deliver, as a form of tax, fixed amounts of specified crops,

Workers pose at the site of a railway

such as sugar or coffee.[37] Much of Java became a Dutch plantation and revenue rose continually through the

tunnel under construction in the

nineteenth century which were reinvested into the Netherlands to save it from bankruptcy.[12][37] Between 1830

mountains, 1910.

and 1870, 1 billion guilders were taken from Indonesia, on average making 25 per cent of the annual Dutch

Government budget.[38] The Cultivation System, however, brought much economic hardship to Javanese

peasants, who suffered famine and epidemics in the 1840s.[12]

Critical public opinion in the Netherlands led to much of the Cultivation System's excesses being

eliminated under the agrarian reforms of the "Liberal Period". Dutch private capital flowed in after

1850, especially in tin mining and plantation estate agriculture. The Billiton Company's tin mines

off the eastern Sumatra coast was financed by a syndicate of Dutch entrepreneurs, including the

younger brother of King William III. Mining began in 1860. In 1863 Jacob Nienhuys obtained a

concession from the sultan of Deli (East Sumatra) for a large tobacco estate.[39] From 1870,

producers were no longer compelled to provide crops for exports, but the Indies were opened up to

private enterprise. Dutch businessmen set up large, profitable plantations. Sugar production

doubled between 1870 and 1885; new crops such as tea and cinchona flourished, and rubber was

introduced, leading to dramatic increases in Dutch profits. Changes were not limited to Java, or

agriculture; oil from Sumatra and Kalimantan became a valuable resource for industrialising

Europe. Dutch commercial interests expanded off Java to the outer islands with increasingly more

Map of the Dutch East Indies in 1818

territory coming under direct Dutch control or dominance in the latter half of the 19th century.[12]

However, the resulting scarcity of land for rice production, combined with dramatically increasing

populations, especially in Java, led to further hardships.[12]

The colonial exploitation of Indonesia's wealth contributed to the industrialisation of the Netherlands, while simultaneously laying the foundation for

the industrialisation of Indonesia. The Dutch introduced coffee, tea, cacao, tobacco and rubber and large expanses of Java became plantations

cultivated by Javanese peasants, collected by Chinese intermediaries, and sold on overseas markets by European merchants.[12] In the late 19th century

economic growth was based on heavy world demand for tea, coffee, and cinchona. The government invested heavily in a railroad network (150 miles

long in 1873, 1,200 in 1900), as well as telegraph lines, and entrepreneurs opened banks, shops and newspapers. The Dutch East Indies produced most

of the world's supply of quinine and pepper, over a third of its rubber, a quarter of its coconut products, and a fifth of its tea, sugar, coffee, and oil. The

profit from the Dutch East Indies made the Netherlands one of the world's most significant colonial powers.[12] The Koninklijke PaketvaartMaatschappij shipping line supported the unification of the colonial economy and brought inter-island shipping through to Batavia, rather than through

Singapore, thus focussing more economic activity on Java.[40]

The worldwide recession of the late 1880s and early 1890s saw the commodity prices on which the colony depended collapse. Journalists and civil

servants observed that the majority of the Indies population were no better off than under the previous regulated Cultivation System economy and tens

of thousands starved.[41] Commodity prices recovered from the recession, leading to increased investment in the colony. The sugar, tin, copra and

coffee trade on which the colony had been built thrived, and rubber, tobacco, tea and oil also became principal exports.[42] Political reform increased

the autonomy of the local colonial administration, moving away from central control from the Netherlands, whilst power was also diverged from the

central Batavia government to more localised governing units.

The world economy recovered in the late 1890s and prosperity returned. Foreign investment, especially by the British, were encouraged. By 1900,

foreign-held assets in the Netherlands Indies totalled about 750 million guilders ($300 million), mostly in Java.[43]

Dutch East Indies - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

3 of 14

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dutch_East_Indies

11/02/2014 11:19

After 1900 upgrading the infrastructure of ports and roads was a high priority for the Dutch, with the goal of modernizing the economy, facilitating

commerce, and speeding up military movements. By 1950 Dutch engineers had built and upgraded a road network with 12,000 km of asphalted

surface, 41,000 km of metalled road area and 16,000 km of gravel surfaces.[44] In addition the Dutch built, 7,500 kilometers (4,700 mi) of railways,

bridges, irrigation systems covering 1.4 million hectares (5,400 sq mi) of rice fields, several harbours, and 140 public drinking water systems. Wim

Ravesteijn has said that, "With these public works, Dutch engineers constructed the material base of the colonial and postcolonial Indonesian state."[45]

Social history

See also: Dutch Ethical Policy

In 1898, the population of Java numbered 28 million with another 7 million on Indonesia's outer islands.[46] The first

half of 20th century saw large-scale immigration of Dutch and other Europeans to the colony, where they worked in

either the government or private sectors. By 1930, there were more than 240,000 people with European legal status in

the colony, making up less than 0.5% of the total population.[47] Almost 75% of these Europeans were in fact native

Eurasians known as Indo-Europeans.[48]

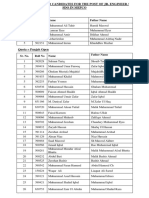

Rank

1930 census of the Dutch East Indies[49]

Group

Number

Percentage

Indigenous islanders

59,138,067 97.4%

Chinese

1,233,214

2.0%

European

240,417

0.4%

Other foreign orientals 115,535

0.2%

Total

60,727,233 100%

As the Dutch secured the islands they eliminated slavery, widow burning, head-hunting, cannibalism, piracy, and

internecine wars.[20] Railways, steamships, postal and telegraph services, and various government agencies all

served to introduce a degree of new uniformity across the colony. Immigration within the archipelago

particularly by ethnic Chinese, Bataks, Javanese, and Bugisincreased dramatically.[50]

Volksraad members in 1918:

D. Birnie (Dutch), Kan Hok

Hoei (Chinese), R. Sastro

Widjono and M.N. Dwidjo

Sewojo (Javanese).

The Dutch colonialists formed a privileged upper social class of soldiers, administrators, managers, teachers and

pioneers. They lived together with the "natives", but at the top of a rigid social and racial caste system.[51][52]

The Dutch East Indies had two legal classes of citizens; European and indigenous. A third class, Foreign

Easterners, was added in 1920.[53]

In 1901 the Dutch adopted what they called the Ethical Policy, under which the colonial government had a duty

'Selamatan' feast in Buitenzorg, a

to further the welfare of the Indonesian people in health and education. Other new measures under the policy

common feast among Javanese

included irrigation programs, transmigration, communications, flood mitigation, industrialisation, and

Muslims.

protection of native industry.[12] Industrialisation did not significantly affect the majority of Indonesians, and

Indonesia remained an agricultural colony; by 1930, there were 17 cities with populations over 50,000 and their combined populations numbered 1.87

million of the colony's 60 million.[24]

Government

Education

The Dutch school system was extended to Indonesians with the most prestigious schools admitting Dutch

children and those of the Indonesian upper class. A second tier of schooling was based on ethnicity with

separate schools for Indonesians, Arabs, and Chinese being taught in Dutch and with a Dutch curriculum.

Ordinary Indonesians were educated in Malay in Roman alphabet with "link" schools preparing bright

Indonesian students for entry into the Dutch-language schools.[54] Vocational schools and programs were set up

by the Indies government to train indigenous Indonesians for specific roles in the colonial economy. Chinese

and Arabs, officially termed "foreign orientals", could not enrol in either the vocational schools or primary

schools.[55]

Graduates of Dutch schools opened their own schools modelled on the Dutch school system, as did Christian

missionaries, Theosophical Societies, and Indonesian cultural associations. This proliferation of schools was

further boosted by new Muslim schools in the Western mould that also offered secular subjects.[54] According

to the 1930 census, 6% of Indonesians were literate, however, this figure recognised only graduates from

Western schools and those who could read and write in a language in the Roman alphabet. It did not include

graduates of non-Western schools or those who could read but not write Arabic, Malay or Dutch, or those who could write in non-Roman alphabets

such as Batak, Javanese, Chinese, or Arabic.[54]

Students of the School Tot Opleiding

Van Indische Artsen (STOVIA) aka

Sekolah Doctor Jawa.

Some of higher education institutions were also established. In 1898 the Dutch East Indies government established a school to train medical doctors,

named School tot Opleiding van Inlandsche Artsen (STOVIA). Many STOVIA graduates later played important roles in Indonesia's national

movement toward independence as well in developing medical education in Indonesia, such as Dr. Wahidin Soedirohoesodo, who established the Budi

Utomo political society. De Technische Hoogeschool te Bandung established in 1920 by the Dutch colonial administration to meet the needs of

technical resources at its colony. One of Technische Hogeschool graduate is Sukarno whom later would lead the Indonesian National Revolution. In

1924, the colonial government again decided to open a new tertiary-level educational facility, the Rechts Hogeschool (RHS), to train civilian officers

and servants. In 1927, STOVIA's status was changed to that of a full tertiary-level institution and its name was changed to Geneeskundige Hogeschool

(GHS). The GHS occupied the same main building and used the same teaching hospital as the current Faculty of Medicine of University of Indonesia.

Dutch East Indies - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

4 of 14

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dutch_East_Indies

11/02/2014 11:19

The old links between the Netherlands and Indonesia are still clearly visible in such technological areas as

irrigation design. To this day, the ideas of Dutch colonial irrigation engineers continue to exert a strong

influence over Indonesian design practices.[56] Moreover the two highest internationally ranking universities of

Indonesia, the University of Indonesia est.1898 and the Bandung Institute of Technology est.1920, were both

founded during the colonial era.[57][58]

Education reforms, and modest political reform, resulted in a small elite of highly educated indigenous

Indonesians, who promoted the idea of an independent and unified "Indonesia" that would bring together

disparate indigenous groups of the Dutch East Indies. A period termed the Indonesian National Revival, the first

half of the 20th century saw the nationalist movement develop strongly, but also face Dutch oppression.[12]

Law and administration

Dutch, Eurasian and Javanese

professors of law at the opening of

the Rechts Hogeschool in 1924.

See also: Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies

Traditional rulers who survived displacement by the Dutch conquests were installed as regents and indigenous

aristocracy became an indigenous civil service. While they lost real control, their wealth and splendour under

the Dutch grew.[24] They were placed under a hierarchy of Dutch officials; the Residents, the Assistant

Residents, and District Officers called Controlers. This indirect rule did not disturb the peasantry and was

cost-effective for the Dutch; in 1900, only 250 European and 1,500 indigenous civil servants, and 16,000 Dutch

officers and men and 26,000 hired native troops, were required to rule 35 million colonial subjects.[59] From

1910, the Dutch created the most centralised state power in Southeast Asia.[20]

Since the VOC era, the highest Dutch authority in the colony resided with the 'Office of the Governor-General'.

During the Dutch East Indies era the Governor-General functioned as chief executive president of colonial

government and served as commander-in-chief of the colonial (KNIL) army. Until 1903 all government officials

and organisations were formal agents of the Governor-General and were entirely dependent on the central

administration of the 'Office of the Governor-General' for their budgets.[60] Until 1815 the Governor-General had the absolute right to ban, censor or

restrict any publication in the colony. The so-called Exorbitant powers of the Governor-General allowed him to exile anyone regarded as subversive

and dangerous to peace and order, without involving any Court of Law.[61]

House of Resident (colonial

administrator) in Surabaya.

Until 1848 the Governor-General was directly appointed by the Dutch monarch, and in later years via the Crown and on

advise of the Dutch metropolitan cabinet. During two periods (18151835 and 18541925) the Governor-General ruled

jointly with an advisory board called the Raad van Indie (Indies Council). Colonial policy and strategy were the

responsibility of the Ministry of Colonies based in The Hague. From 1815 to 1848 the Ministry was under direct

authority of the Dutch King. In the 20th century the colony gradually developed as a state distinct from the Dutch

metropole with treasury separated in 1903, public loans being contracted by the colony from 1913, and quasi diplomatic

ties were established with Arabia to manage the Haji pilgrimage from the Dutch East Indies. In 1922 the colony came

on equal footing with the Netherlands in the Dutch constitution, while remaining under the Ministry of Colonies.[62]

Governor-General's palace in

A People's Council called the Volksraad for the Dutch East Indies commenced

Batavia (1880-1900).

in 1918. The Volksraad was limited to an advisory role and only a small portion

of the indigenous population were able to vote for its members. The Council

comprised 30 indigneous members, 25 European and 5 from Chinese and other populations, and was

reconstituted every four years. In 1925 the Volksraad was made a semilegislative body; although decisions were

still made by the Dutch government, the governor-general was expected to consult the Volksraad on major

issues. The Volksraad was dissolved in 1942 during the Japanese occupation.[63]

The Dutch government adapted the Dutch codes of law in its colony.

The highest court of law, the Supreme Court in Batavia, dealt with

Opening of the Volksraad, Batavia 18

appeals and monitored judges and courts throughout the colony. Six

May 1918.

Councils of Justice (Raad van Justitie) dealt mostly with crime

committed by people in the European legal class[64] and only indirectly

with the indigenous population. The Land Councils (Landraden) dealt with civil matters and less serious

offences like estate divorces, and matrimonial disputes. The indigenous population was subject to their

respective adat law and to indigenous regents and district courts, unless cases were escalated before Dutch

judges.[65][66] Following Indonesian independence, the Dutch legal system was adopted and gradually a

national legal system based on Indonesian precepts of law and justice was established.[67]

By 1920 the Dutch had established 350 prisons throughout the colony. The Meester Cornelis prison in Batavia

incarcerated the most unruly inmates. In Sawah Loento prison on Sumatra prisoners had to perform manual

Supreme Court Building, Batavia.

labour in the coal mines. Separate prisons were built for juveniles (West Java) and for women. In the female

Boeloe prison in Semarang inmates had the opportunity to learn a profession during their detention, such as

sewing, weaving and making batik. This training was held in high esteem and helped re-socialise women once they were outside the correctional

facility.[68][69] In response to the communist uprising of 1926 the prison camp Boven-Digoel was established in New Guinea. As of 1927 political

prisoners, including indigenous Indonesians espousing Indonesian independence, were 'exiled' to the outer islands.[70]

Politically, the highly centralised power structure, including the exorbitant powers of exile and censorship,[71] established by the Dutch administration

was carried over into the new Indonesian republic.[20]

Administrative divisions

The Dutch East Indies was divided into residencies.[72] In 1942, the residencies were:-

Dutch East Indies - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

5 of 14

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dutch_East_Indies

Name

Dutch name

Local name

11/02/2014 11:19

Area Population

Current English (km) (1942)

name

Modern area

Primary resource(s)

Aceh

Residency of

Aceh and

Dependencies

n/a

Aceh, consist of division (afdeeling) of GrootAtjeh, Nordkust van Atjeh, Oostkust van

n/a

opium,gold

Atjeh, Gajo en Alaslanden and Westkust van

Atjeh

Residentie Tapanoeli

Tapanuli

Residency of

Tapanuli

n/a

western part of North Sumatra, consist of

n/a division (afdeeling) of Sibolga en Omstreken, camphor

Nias, Bataklanden and Padang Sidempoean

Residentie Oostkust

van Sumatra

Residency of

Sumatra Timur Sumatra's East

Coast

n/a

eastern part of North Sumatra and northern

part of Riau, consist of division (afdeeling) of

n/a Langkat, Deli en Serdang, Asahan and

tobacco

Simaloengoen en Karolanden; with

municipality (stadsgemeente) of Medan

Residentie Sumatra's

Westkust

Residency of

Sumatra Barat Sumatra's West

Coast

n/a

West Sumatra including Mentawai Islands,

consist of division (afdeeling) of Padangsche

n/a Bovenlanden, Agam, Solok, Limapoeloe Koto coal,black pepper,salt

and Zuid Benedenlanden; with municipality

(stadsgemeente) of Padang

Residentie Riouw en

Onderhoorigheden

Riau

Residency of

Riau and

Dependencies

n/a

southern part of Riau and Riau Islands, consist

n/a of division (afdeeling) of Siak, Benkalis,

oil,fish

Indragiri and Tandjoengpinang

Residentie Djambi

Jambi

Residency of

Jambi

n/a

n/a

Jambi, consist of division (afdeeling) of

Djambi

black pepper

Residentie Benkoelen

Bengkulu

Residency of

Bengkulu

n/a

n/a

Bengkulu, consist of division (afdeeling) of

Benkoelen

black pepper

Residentie Palembang Palembang

Residency of

Palembang

n/a

South Sumatra, consist of division (afdeeling)

of Palembang Bovenlanden, Palembang

n/a Benedenlanden and Ogan en Komering-oeloe; black pepper

with municipality (stadsgemeente) of

Palembang

Residentie Banka en

Onderhoorigheden

Bangka

Residency of

Bangka and

Dependencies

n/a

n/a

Bangka and Belitung Islands, consist of

division (afdeeling) of Banka and Blitong

Residentie

Lampongsche

Districten

Lampung

Residency of

Lampung District

n/a

n/a

Lampung, consist of division (afdeeling) of

Teloek Betoeng

Residentie Bantam

Banten

Residency of

Banten

n/a

n/a

Banten consist of regency (regentschap) of

Serang, Lebak and Pandeglang

black

pepper,gold,poultry

Residentie Batavia

Betawi

Residency of

Batavia

n/a

n/a

Jakarta and surroundings, consist of regency

(regentschap) of Batavia, Meester-Cornelis

and Krawang; with municipality

(stadsgemeente) of Batavia

rice,coffee

n/a

Bogor and surroundings, consist of regency

(regentschap) of Buitenzorg, Soekaboemi and

n/a

coffee

Tjiandjoer; with municipality (stadsgemeente)

of Buitenzorg and Soekaboemi

n/a

Bandung and surroundings, consist of regency

(regentschap) of Bandoeng, Soemedang,

tea,coffee,quinine

n/a

Tasikmalaja, Tjiamis and Garoet; with

municipality (stadsgemeente) of Bandoeng

n/a

Cirebon and surroundings, consist of regency

(regentschap) of Cheribon, Koeningan,

n/a

Indramajoe and Madjalengka; with

municipality (stadsgemeente) of Cheribon

black pepper,fish

fish,indigo,rice,sugar

Residentie Atjeh en

Onderhoorigheden

Residentie Buitenzorg Bogor

Residency of

Buitenzorg

Residentie Preanger

Priangan

Residency of

Preanger

Cirebon

Residency of

Cirebon

Residentie Cheribon

Residentie Pekalongan Pekalongan

Residency of

Pekalongan

n/a

Pekalongan, Tegal and surroundings, consist

of regency (regentschap) of Pekalongan,

n/a Batang, Pemalang, Tegal and Brebes; with

municipality (stadsgemeente) of Pekalongan

and Tegal

Residentie Samarang

Residency of

Semarang

n/a

n/a

Semarang

Dutch East Indies - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Semarang and surroundings, consist of

regency (regentschap) of Samarang, Kendal,

Demak and Grobogan; with municipality

tin

timber,indigo

6 of 14

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dutch_East_Indies

11/02/2014 11:19

(stadsgemeente) of Samarang and Salatiga

Residentie DjaparaRembang

JeparaRembang

Residentie Banjoemas Banyumas

Residency of

Jepara-Rembang

Residency of

Banyumas

n/a

Jepara, Rembang and surroundings, consist of

n/a regency (regentschap) of Pati, Djapara,

timber,rice,cotton

Rembang, Blora and Koedoes

n/a

Banyumas, Purwokerto and surroundings,

consist of regency (regentschap) of

n/a

Banjoemas, Poerwokerto, Poerbolinggo,

Tjilatjap, Karanganjar and Bandjarnegara

oil

Residentie Kedoe

Kedu

Residency of

Kedu

n/a

Magelang and surroundings, consist of

regency (regentschap) of Magelang,

n/a Wonosobo, Temanggoeng, Poerworedjo,

tobacco

Koetoardjo and Keboemen; with municipality

(stadsgemeente) of Magelang

Residentie Jogjakarta

Yogyakarta

Residency of

Yogyakarta

n/a

Yogyakarta, consist of regency (regentschap)

n/a of Adikarto, Koelon-Progo, Jogjakarta,

Bantoel and Goenoeng-Kidul

Residentie Klaten

Klaten

Residency of

Klaten

n/a

n/a

Residentie Soerakarta

Surakarta

Residency of

Surakarta

n/a

Surakarta, consist of regency (regentschap) of

n/a Sragen, Soerakarta, Mangkoenagaran and

tobacco

Wonogiri

Residentie

Bodjonegoro

Bojonegoro

Residency of

Bojonegoro

n/a

Bojonegoro and surroundings, consist of

n/a regency (regentschap) of Bodjonegoro,

Toeban, Grisse and Lamongan

Residentie Madioen

Madiun

Residency of

Madiun

n/a

n/a

n/a

Kediri and surroundings, consist of regency

(regentschap) of Kediri, Ngandjoek, Blitar,

n/a Toeloengagoeng and Trenggalek; with

municipality (stadsgemeente) of Kediri and

Blitar

tobacco

n/a

Malang and surroundings, consist of regency

(regentschap) of Malang, Pasoeroean and

n/a

Bangil; with municipality (stadsgemeente) of

Malang and Pasoeroean

fruit

n/a

Surabaya and surroundings, consist of regency

(regentschap) of Soerabaja, Sidoardjo,

n/a

fish

Modjokerto and Djombang; with municipality

(stadsgemeente) of Soerabaja

Klaten and surroundings, consist of regency

(regentschap) of Klaten and Bojolali

Madiun and surroundings, consist of regency

(regentschap) of Madioen, Magetan, Ngawi,

Ponorogo and Patjitan; with municipality

(stadsgemeente) of Madioen

tobacco

tobacco

fish

sugar

Kediri

Residency of

Kediri

Malang

Residency of

Malang

Surabaya

Residency of

Surabaya

Residentie

Probolinggo

Probolinggo

Residency of

Probolinggo

n/a

Probolinggo and surroundings, consist of

regency (regentschap) of Probolinggo,

n/a

sulphur

Kraksaan and Loemadjang; with municipality

(stadsgemeente) of Probolinggo

Residentie Besoeki

Besuki

Residency of

Besuki

n/a

Banyuwangi and surroundings, consist of

n/a regency (regentschap) of Bondowoso,

Panaroekan, Djember and Banjoewangi

tobacco

Residentie Madoera

Madura

Residency of

Madura

n/a

Madura, consist of regency (regentschap) of

n/a Bangkalan, Sampang, Pamekasan and

Soemenep

salt

Residentie

Westerafdeeling van

Borneo

Kalimantan

Barat

Residency of

Western

Kalimantan

n/a

West Kalimantan, consist of division

n/a (afdeeling) of Singkawang, Pontianak,

Ketapang and Sintang

gold

Residentie Zuider en

Oosterafdeeling van

Borneo

Kalimantan

Selatan dan

Timur

Residency of

South and East

Kalimantan

n/a

Central Kalimantan, South Kalimantan, East

Kalimantan and North Kalimantan, consist of

n/a division (afdeeling) of Barito, Bandjermasin,

Hoeloe Soengei, Pasir, Samarinda and

Boeloengan en Berau

diamond,oil,black

pepper

Sulawesi

Residency of

Celebes and

Dependencies

n/a

South Sulawesi, West Sulawesi and Southeast

Sulawesi, consist of division (afdeeling) of

n/a Makassar, Bone, Pare-pare, Mandar, Loewoe fish,cotton,gold

and Boetoeng en Laiwoei; with municipality

(stadsgemeente) of Makassar

Residentie Kediri

Residentie Malang

Residentie Soerabaja

Residentie Celebes en

Onderhoorigheden

Dutch East Indies - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

7 of 14

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dutch_East_Indies

11/02/2014 11:19

Residentie Manado

Manado

Residency of

Manado

n/a

Central Sulawesi, Gorontalo and North

Sulawesi, consist of division (afdeeling) of

n/a Poso, Donggala, Gorontalo, Manado and

fish

Sangihe en Talaud eilanden; with municipality

(stadsgemeente) of Manado

Residentie Bali en

Lombok

Bali dan

Lombok

Residency of Bali

and Lombok

n/a

n/a

Timor

Residency of

Timor and

Dependencies

n/a

eastern part of West Nusa Tenggara and East

Nusa Tenggara, consist of division (afdeeling)

n/a

sandalwood

of Soembawa, Soemba, Flores and Timor en

eilanden

Maluku

Residency of

Molucca

n/a

North Maluku and Maluku, consist of division

(afdeeling) of Ternate, Amboina and Tual;

n/a

clove,nutmeg,mace

with municipality (stadsgemeente) of

Amboina

n/a

West Papua and Papua, consist of division

(afdeeling) of West-Nieuw-Guinea, Fak Fak,

n/a Geelvinkbaai, Centraal-Nieuw-Guinea,

Noordkust van Nieuw-Guinea and Zudkust

van Nieuw-Guinea

Residentie Timor en

Onderhoorigheden

Residentie Molukken

Residentie NieuwGuinea

Papua

Residency of

New Guinea

Bali and Lombok, consist of division

(afdeeling) of Bali and Lombok

rice

timber

Armed forces

Main articles: Royal Dutch East Indies Army, Royal Netherlands East Indies Army Air Force, and

Government Navy

The Royal Dutch East Indies Army (KNIL) and the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army Air Force (ML-KNIL)

were established in 1830 and 1915 respectively. Naval forces of the Royal Netherlands Navy were based in

Surabaya, but were never part of the KNIL. The KNIL was a separate branch of the Royal Netherlands Army,

commanded by the Governor-General and funded by the colonial budget. The KNIL was not allowed to recruit

Dutch conscripts and had the nature of a 'Foreign Legion' recruiting not only Dutch volunteers, but many other

European nationalities (especially German, Belgian and Swiss mercenaries).[73] While most officers were

Europeans, the majority of soldiers were indigenous Indonesians, the largest contingent of which were Javanese

and Sundanese.[74]

Decorated indigenous KNIL soldiers,

1927.

Dutch policy before the 1870s was to take full charge of strategic points and work out treaties with the local

leaders elsewhere so they would remain in control and cooperate. The policy failed in Aceh, in northern Sumatra, where the sultan tolerated pirates

who raided commerce in the Strait of Malacca. Britain was a protector of Aceh and it gave the Netherlands permission to eradicate the pirates. The

campaign quickly drove out the sultan but across Aceh numerous local Muslim leaders mobilized and fought the Dutch in four decades of very

expensive guerrilla war, with high levels of atrocities on both sides.[75]

Colonial military authorities tried to forestall a war against the population by means of a strategy of awe. When a guerrilla war did take place the

Dutch used either a slow, violent occupation or a campaign of destruction.[76] By 1900 the archipelago was considered "pacified" and the KNIL was

mainly involved with military police tasks. The nature of the KNIL changed in 1917 when the colonial government introduced obligatory military

service for all male conscripts in the European legal class[77] and in 1922 a supplemental legal enactment introduced the creation of a Home guard

(Dutch: Landstorm) for European conscripts older than 32.[78] Petitions by Indonesian nationalists to establish military service for indigenous people

were rejected. In July 1941 the Volksraad passed law creating a native militia of 18,000 by a majority of 43 to 4, with only the moderate Great

Indonesia Party objecting. After the declaration of war with Japan, over 100,000 natives volunteered.[79] The KNIL hastily and inadequately attempted

to transform into modern military force able to protect the Dutch East Indies from Imperial Japanese invasion. On the eve of the Japanese invasion in

December 1941, Dutch regular troops in the East Indies comprised about 1,000 officers and 34,000 men, of whom 28,000 were indigenous. During the

Dutch East Indies campaign of 194142 the KNIL and the Allied forces were quickly defeated.[80] All European soldiers, which in practice included

all able bodied Indo-European males were interned by the Japanese as POW's. 25% of the POW's did not survive their internment.

Following World War II, a reconstituted KNIL joined with Dutch Army troops to re-establish colonial "law and order". Despite two successful military

campaigns in 1947 and 1948, Dutch efforts to re-establish their colony failed and the Netherlands recognised Indonesian sovereignty in December

1949.[81] The KNIL was disbanded by 26 July 1950 with its indigenous personnel being given the option of demobilising or joining the Indonesian

military.[82] At the time of disbandment the KNIL numbered 65,000, of whom 26,000 were incorporated into the new Indonesian Army. The remainder

were either demobilised or transferred to the Netherlands Army.[83] Key officers in the Indonesian National Armed Forces that were former KNIL

soldiers include: Suharto second president of Indonesia, Nasution supreme commander of the Indonesian army and E.Kawilarang founder of the elite

special forces Kopassus.

Culture

Language and literature

See also: Dutch Indies literature

Across the archipelago, hundreds of native languages are used, and Malay or Portuguese Creole, the existing languages of trade were adopted. Prior to

1870, when Dutch colonial influence was largely restricted to Java, Malay was used in government schools and training programs such that graduates

could communicate with groups from other regions who immigrated to Java.[84] The colonial government sought to standardise Malay based on the

Dutch East Indies - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

8 of 14

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dutch_East_Indies

11/02/2014 11:19

version from Riau and Malacca, and dictionaries were commissioned for governmental communication and

schools for indigenous peoples.[85] In the early 20th century, Indonesia's independence leaders adopted a form

of Malay from Riau, and called it Indonesian. In the latter half of the nineteenth century, the rest of the

archipelago, in which hundreds of language groups were used, was brought under Dutch control. In extending

the native education program to these areas, the government stipulated this "standard Malay" as the language of

the colony.[86]

Dutch was not made the official language of the colony and was not widely used by the indigenous Indonesian

population.[87] The majority of legally acknowledged Dutchmen were bi-lingual Indo Eurasians.[88] Dutch was

only used by a limited educated elite, and in 1942, around two percent of the total population in the Dutch East

Indies spoke Dutch including over 1 million indigenous Indonesians.[89] A number of Dutch loan words are

used in present-day Indonesian, particularly technical terms (see List of Dutch loan words in Indonesian). These

words generally had no alternative in Malay and were adopted into the Indonesian vocabulary giving a

linguistic insight into which concepts are part of the Dutch colonial heritage. Hendrik Maier of the University of

California says that about a fifth of contemporary Indonesian language can be traced to Dutch.[90]

Perhimpunan Pelajar-Pelajar

Indonesia (Indonesian Students

Union) delegates in Youth Pledge, an

important event where Indonesian

language was decided to be the

national language. 1928

Dutch language literature has been inspired by both colonial and post-colonial Indies from the Dutch Golden Age to the present day. It includes Dutch,

Indo-European and Indonesian authors. Its subject matter thematically revolves around the Dutch colonial era, but also includes postcolonial discourse.

Masterpieces of this genre include Multatuli's Max Havelaar: Or The Coffee Auctions of the Dutch Trading Company, Louis Couperus's Hidden Force,

E. du Perron's Country of Origin, and Maria Dermot's The Ten Thousand Things.[91][92]

Most Dutch literature was written by Dutch and Indo-European authors, however, in the first half of the twentieth century under the Ethical Policy,

indigenous Indonesian authors and intellectuals came to the Netherlands to study and work. They wrote Dutch language literary works and published

literature in literary reviews such as Het Getij, De Gemeenschap, Links Richten and Forum. By exploring new literary themes and focusing on

indigenous protagonists, they drew attention to indigenous culture and the indigenous plight. Examples include the Javanese prince and poet Noto

Soeroto, a writer and journalist, and the Dutch language writings of Soewarsih Djojopoespito, Chairil Anwar, Kartini, Sutan Sjahrir and Sukarno.[93]

Much of the postcolonial discourse in Dutch Indies literature has been written by Indo-European authors led by the "avant garde visionary" Tjalie

Robinson, who is the best read Dutch author in contemporary Indonesia[94] and second generation Indo-European immigrants like Marion Bloem.

Visual art

The natural beauty of East Indies has inspired the works of artists and painters, that mostly capture the romantic

scenes of colonial Indies. The term Mooi Indie (Dutch for "Beautiful Indies") was originally coined as the title

of 11 reproductions of Du Chattel's watercolor paintings which depicted the scene of East Indies published in

Amsterdam in 1930. The term became famous in 1939 after S. Sudjojono used it to mock the painters that

merely depict all pretty things about Indies.[95] Mooi Indie later would identified as the genre of painting that

occurred during the colonial East Indies that capture the romantic depictions of the Indies as the main themes;

mostly natural scenes of mountains, volcanos, rice paddies, river valleys, villages, with scenes of native

servants, nobles, and sometimes bare-chested native women. Some of the notable Mooi Indie painters are

European artists: F.J. du Chattel, Manus Bauer, Nieuwkamp, Isaac Israel, PAJ Moojen, Carel Dake and

The romantic depiction of De Grote

Romualdo Locatelli; East Indies-born Dutch painters: Henry van Velthuijzen, Charles Sayers, Ernest Dezene,

Postweg near Buitenzorg.

Leonard Eland and Jan Frank; Native painters: Raden Saleh, Mas Pirngadi, Abdullah Surisubroto, Wakidi,

Basuki Abdullah, Mas Soeryo Soebanto and Henk Ngantunk; and also Chinese painters: Lee Man Fong, Oei

Tiang Oen and Biau Tik Kwie. These painters usually exhibit their works in art galleries such as Bataviasche Kuntkringgebouw, Theosofie

Vereeniging, Kunstzaal Kolff & Co and Hotel Des Indes.

Theatre and film

See also: List of films of the Dutch East Indies, List of film producers of the Dutch East Indies, and List of film directors of the Dutch East Indies

A total of 112 fictional films are known to have been produced in the Dutch East Indies between 1926 and the

colony's dissolution in 1949. The earliest motion pictures, imported from abroad, were shown in late 1900,[96]

and by the early 1920s imported serials and fictional films were being shown, often with localised names.[97]

Dutch companies were also producing documentary films about the Indies to be shown in the Netherlands.[98]

The first locally-produced film, Loetoeng Kasaroeng, was directed by L. Heuveldorp and released on

31 December 1926.[99] Between 1926 and 1933 numerous other local productions were released. During the

mid-1930s, production dropped as a result of the Great Depression.[100] The rate of production declined again

after the Japanese occupation beginning in early 1942, closing all but one film studio.[101] The majority of films

produced during the occupation were Japanese propaganda shorts.[102] Following the Proclamation of

Indonesian Independence in 1945 and during the ensuing revolution several films were made, by both

pro-Dutch and pro-Indonesian backers.[103][104]

Cinema Bioscoop Mimosa in Batu,

Java dated 1941.

Generally films produced in the Indies dealt with traditional stories or were adapted from existing works.[105] The early films were silent, with Karnadi

Anemer Bangkong (Karnadi the Frog Contractor; 1930) generally considered the first talkie;[106] later films would be in Dutch, Malay, or an

indigenous language. All were black-and-white. The American visual anthropologist Karl G. Heider writes that all films from before 1950 are lost.[107]

However, JB Kristanto's Katalog Film Indonesia (Indonesian Film Catalogue) records several as having survived at Sinematek Indonesia's archives,

and Biran writes that several Japanese propaganda films have survived at the Netherlands Government Information Service.[108]

Theatre plays by playwrights such as Victor Ido (18691948) were performed at the Shouwburg Weltevreden, now known as Gedung Kesenian Jakarta.

A less elite form of theatre, popular with both European and indigenous people, were the traveling Indo theatre shows known as Komedie Stamboel,

made popular by Auguste Mahieu (18651903).

Dutch East Indies - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

9 of 14

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dutch_East_Indies

11/02/2014 11:19

Science

The rich nature and culture of the Dutch East Indies attracted European intellectuals, scientists and researchers.

Some notable scientists that conducted most of their important research in the East Indies archipelago are

Teijsmann, Junghuhn, Eijkman and Wallace. Many important art, culture and science institutions were

established in Dutch East Indies. For example the Bataviaasch Genootschap van Kunsten en Wetenschappen,

(Royal Batavian Society of Arts and Sciences), the predecessor of the National Museum of Indonesia, was

established in 1778 with the aim to promote research and publish findings in the field of arts and sciences,

especially history, archaeology, ethnography and physics. The Bogor Botanical Gardens with Herbarium

Bogoriense and Museum Zoologicum Bogoriense was a major center for botanical research established in 1817,

with the aim to study the flora and fauna of the archipelago.

Cuisine

Museum and lab of the Buitenzorg

Plantentuin.

See also: Indonesian cuisine

The Dutch colonial families through their domestic helps and cooks were exposed to Indonesian cuisine, as the

result they have developed a taste for native tropical spices and dishes. A notable Dutch East Indies colonial

dish is rijsttafel, the rice table that consists of 7 to 40 popular dishes from across the colony. More an

extravagant banquet than a dish, the Dutch colonials introduced the rice table not only so they could enjoy a

wide array of dishes at a single setting but also to impress visitors with the exotic abundance of their

colony.[109]

Through colonialism the Dutch introduced European dishes such as bread, cheese, barbecued steak and

pancake. As the producer of cash crops; coffee and tea were also popular in the colonial East Indies. Bread,

Dutch family enjoying a succulent

butter and margarine, sandwiches filled with ham, cheese or fruit jam, poffertjes, pannekoek and Dutch cheeses

Rijsttafel dinner, 1936.

were commonly consumed by colonial Dutch and Indos during the colonial era. Some of the native upperclass

ningrat (nobles) and a few educated native were exposed to European cuisine, and it was held with high esteem

as the cuisine of upperclass elite of Dutch East Indies society. This led to the adoption and fusion of European cuisine into Indonesian cuisine. Some

dishes which were created during the colonial era are Dutch influenced: they include selat solo (solo salad), bistik jawa (Javanese beef steak), semur

(from Dutch smoor), sayur kacang merah (brenebon) and sop buntut. Cakes and cookies also can trace their origin to Dutch influences; such as kue

bolu (tart), pandan cake, lapis legit (spekkoek), spiku (lapis Surabaya), klappertaart (coconut tart), and kaastangel (cheese cookies). Kue cubit

commonly found in front of schools and marketplaces are believed to be derived from poffertjes.[110]

Architecture

Main article: Colonial architecture of Indonesia

The 16th and 17th century arrival of European powers in Indonesia introduced masonry construction to Indonesia where previously timber and its

by-products had been almost exclusively used. In the 17th and 18th centuries, Batavia was a fortified brick and masonry city.[111] For almost two

centuries, the colonialists did little to adapt their European architectural habits to the tropical climate.[112] They built row houses which were poorly

ventilated with small windows, which was thought as protection against tropical diseases coming from tropical air.[112] Years later the Dutch learnt to

adapt their architectural styles with local building features (long eaves, verandahs, porticos, large windows and ventilation openings),[113] and the 19th

century Indo-European hybrid villa was one of the first colonial buildings to incorporate Indonesian architectural elements and adapt to the

climate.[114]

From the end of the 19th century, significant improvements to technology, communications and transportation

brought new wealth to Java. Modernistic buildings, including train stations, business hotels, factories and office

blocks, hospitals and education institutions, were influenced by international styles. The early 20th century

trend was for modernist influencessuch as art-decobeing expressed in essentially European buildings with

Indonesian trim. Practical responses to the environment carried over from the earlier Indo-European hybrids,

included overhanging eaves, larger windows and ventilation in the walls.[115] The largest stock of colonial era

buildings are in the large cities of Java, such as Bandung, Jakarta, Semarang, and Surabaya. Notable architects

and planners include Albert Aalbers, Thomas Karsten, Henri Maclaine Pont, J. Gerber and C.P.W.

Schoemaker.[116] In the first three decades of the 20th century, the Department of Public Works funded major

public buildings and introduced a town planning program under which the main towns and cities in Java and

Sumatra were rebuilt and extended.[117]

Ceremonial Hall, Bandung Institute

of Technology, Bandung, by architect

Henri Maclaine-Pont

A lack of development in the Great Depression, the turmoil of the Second World War and the Indonesia's independence struggle of the 1940s, and

economic stagnation during the politically turbulent 1950s and 60s, meant that much colonial architecture has been preserved through to recent

decades.[118] Colonial homes were almost always the preserve of the wealthy Dutch, Indonesian and Chinese elites, however the styles were often rich

and creative combinations of two cultures, so much so that the homes remain sought after into 21st century.[114] Native architecture was arguably more

influenced by the new European ideas than colonial architecture was influenced by Indonesian styles; and these Western elements continue to be a

dominant influence on Indonesia's built environment today.

Colonial heritage in the Netherlands

In The Dutch Golden Age of the 17th century, the Netherlands urbanised considerably, mostly financed by corporate revenue from the Asian trade

monopolies.[citation needed] Social status was based on merchants' income, which reduced feudalism and considerably changed the dynamics of Dutch

society.

When the Dutch Royal Family was established in 1815, much of its wealth came from Colonial trade.[119]

Dutch East Indies - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

10 of 14

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dutch_East_Indies

11/02/2014 11:19

Universities such as the Royal Leiden University founded in the 16th century have developed into leading

knowledge centres about Southeast Asian and Indonesian studies.[120] Leiden University has produced

academics such as Colonial adviser Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje who specialised in native oriental

(Indonesian) affairs, and it still has academics who specialise in Indonesian languages and cultures. Leiden

University and in particular KITLV are educational and scientific institutions that to this day share both an

intellectual and historical interest in Indonesian studies. Other scientific institutions in the Netherlands include

the Amsterdam Tropenmuseum, an anthropological museum with massive collections of Indonesian art, culture,

ethnography and anthropology.[56]

The traditions of the KNIL are maintained by the Regiment Van Heutsz of the modern Royal Netherlands Army

and the dedicated Bronbeek Museum, a former home for retired KNIL soldiers, exists in Arnhem to this day.

Many surviving colonial families and their descendants who moved back to the Netherlands after Independence

tended to look back on the colonial era with a sense of the power and prestige they had in the colony, with such

items as the 1970s book Tempo Doeloe (Old times) by author Rob Nieuwenhuys, and other books and materials

that became quite common in the 1970s and 1980s.[122] Moreover since the 18th century Dutch literature has a

large number of established authors, such as Louis Couperus, the writer of "The Hidden Force", taking the

colonial era as an important source of inspiration.[123] In fact one of the great masterpieces of Dutch literature is

the book "Max Havelaar" written by Multatuli in 1860.[124]

The majority of Dutchmen that repatriated to the Netherlands after and during the Indonesian revolution are

Indo (Eurasian), native to the islands of the Dutch East Indies. This relatively large Eurasian population had

developed over a period of 400 years and were classified by colonial law as belonging to the European legal

community.[125] In Dutch they are referred to as 'Indische Nederlanders' (Indies Dutchmen) or Indo (short for

Indo-European). Of the 296,200 so called Dutch 'repatriants' only 92,200 were expatriate Dutchmen born in the

Netherlands.[126]

Dutch imperial imagery representing

the Dutch East Indies (1916). The

text reads "Our most precious jewel".

Including their 2nd generation descendants, they are currently the largest foreign born group in the Netherlands. In 2008,

the Dutch Census Buro for Statistics (CBS)[127] registered 387,000 first and second generation Indos living in the

Netherlands.[128] Although considered fully assimilated into Dutch society, as the main ethnic minority in the Netherlands,

these 'Repatriants' have played a pivotal role in introducing elements of Indonesian culture into Dutch mainstream culture.

Practically each town in the Netherlands will have a 'Toko' (Dutch Indonesian Shop) or Indonesian restaurant[129] and

many 'Pasar Malam' (Night market in Malay/Indonesian) fairs are organised throughout the year.

Many Indonesian dishes and foodstuffs have become commonplace in the Netherlands. Rijsttafel, a colonial culinary

concept, and dishes such as Nasi goreng and sateh are still very popular in the Netherlands.[110]

See also

Freemasonry in the Dutch East Indies

List of colonial buildings and structures in Jakarta

Postage stamps and postal history of the Dutch East Indies

Spanish East Indies

Dutch newsreel dated

1927 showing a Dutch

East Indian fair in the

Netherlands featuring

Indo and Indigenous

people from the Dutch

East Indies performing

traditional dance and

music in traditional

attire.[121]

Notes

1. ^ Friend (1942), Vickers (2003), Ricklefs (1991), Reid (1974), Taylor

(2003).

2. ^ Jonathan Hart, Empires and Colonies, page 200 (http://books.google.co.id

/books?id=LnevC1FYdnEC&pg=PA201&

dq=Empires+and+Colonies,+Indonesia+and+Dutch&hl=id&

sa=X&ei=-GElT4rTMcbprAe-gKGZCA&

ved=0CC0Q6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=Empires%20and%20Colonies

%2C%20Indonesia%20and%20Dutch&f=false)

3. ^ Booth, Anne, et al. Indonesian Economic History in the Dutch Colonial

Era (1990), Ch 8

4. ^ R.B. Cribb and A. Kahin, p. 118

5. ^ Robert Elson, The idea of Indonesia: A history (2008) pp 1-12

6. ^ Dagh-register gehouden int Casteel Batavia vant passerende daer ter

plaetse als over geheel Nederlandts-India anno 16241629."English: "The

official register at Catle Bavaria, of the census of the Dutch East Indies

VOC. 1624.

7. ^ Gouda, Frances. Dutch Culture Overseas: Colonial Practice in the

Netherlands Indies, 1900-1942 (1996) online (http://www.questia.com

/read/37803874/dutch-culture-overseas-colonial-practice-in-thenetherlands)

8. ^ Taylor (2003)

9. ^ a b c Ricklefs (1991), p. 27

10. ^ a b Vickers (2005), p. 10

11. ^ Ricklefs (1991), p. 110; Vickers (2005), p. 10

12. ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l *Witton, Patrick (2003). Indonesia. Melbourne: Lonely

Planet. pp. 2325. ISBN 1-74059-154-2.

13. ^ Luc Nagtegaal, Riding the Dutch Tiger: The Dutch East Indies Company

and the Northeast Coast of Java, 16801743 (1996)

Dutch East Indies - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

14. ^ Schwarz, A. (1994). A Nation in Waiting: Indonesia in the 1990s.

Westview Press. pp. 34. ISBN 1-86373-635-2.

15. ^ Kumar, Ann (1997). Java. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions. p. 44.

ISBN 962-593-244-5.

16. ^ Ricklefs (1991), pp. 111114

17. ^ a b c Ricklefs (1991), p. 131

18. ^ Vickers (2005), p. 10; Ricklefs (1991), p. 131

19. ^ Ricklefs (1991), p. 142

20. ^ a b c d e f g Friend (2003), p. 21

21. ^ Ricklefs (1991), pp. 138-139

22. ^ Vickers (2005), p. 13

23. ^ a b c Vickers (2005), p. 14

24. ^ a b c Reid (1974), p. 1.

25. ^ Morison (1948), p. 191

26. ^ Ricklefs (1991), p. 195

27. ^ L., Klemen, 19992000, The Netherlands East Indies 194142,

"Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 19411942

(http://www.dutcheastindies.webs.com/index.html)".

28. ^ Shigeru Sat: War, nationalism, and peasants: Java under the Japanese

occupation, 19421945 (1997), p. 43

29. ^ Japanese occupation of Indonesia

30. ^ Encyclopdia Britannica Online (2007). "Indonesia :: Japanese

occupation" (http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-22819/Indonesia).

Retrieved 2007-01-21. "Though initially welcomed as liberators, the

Japanese gradually established themselves as harsh overlords. Their

policies fluctuated according to the exigencies of the war, but in general

their primary object was to make the Indies serve Japanese war needs."

11 of 14

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dutch_East_Indies

31. ^ Gert Oostindie and Bert Paasman (1998). "Dutch Attitudes towards

Colonial Empires, Indigenous Cultures, and Slaves" (http://muse.jhu.edu

/journals/eighteenth-century_studies/v031/31.3oostindie.html). EighteenthCentury Studies 31 (3): 349355. doi:10.1353/ecs.1998.0021

(http://dx.doi.org/10.1353%2Fecs.1998.0021).; Ricklefs, M.C. (1993).

History of Modern Indonesia Since c.1300, second edition. London:

MacMillan. ISBN 0-333-57689-6.

32. ^ Vickers (2005), page 85

33. ^ Ricklefs (1991), p. 199

34. ^ Cited in: Dower, John W. War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the

Pacific War (1986; Pantheon; ISBN 0-394-75172-8)

35. ^ Dick, et al. (2002)

36. ^ Ricklefs (1991), p 119

37. ^ a b Taylor (2003), p. 240

38. ^ The Jakarta Globe (http://www.thejakartaglobe.com/opinion/indonesiasinfrastructure-problems-a-legacy-from-dutch-colonialism/437111)

39. ^ Dick, et al. (2002), p. 95

40. ^ Vickers (2005), p. 20

41. ^ Vickers (2005), p. 16

42. ^ Vickers (2005), p. 18

43. ^ Dick, et al. (2002), p. 97

44. ^ Marie-Louise ten Horn-van Nispen and Wim Ravesteijn, "The road to an

empire: Organisation and technology of road construction in the Dutch East

Indies, 1800-1940," Journal of Transport History (2009) 10#1 pp 40-57

45. ^ Wim Ravesteijn, "Between Globalization and Localization: The Case of

Dutch Civil Engineering in Indonesia, 18001950," Comparative

Technology Transfer and Society, 5#1 (2007) pp. 3264, quote p 32. online

(http://muse.jhu.edu/login?uri=/journals

/comparative_technology_transfer_and_society/v005/5.1ravesteijn.html)

46. ^ Furnivall, J.S. (1939 [reprinted 1967]). Netherlands India: a Study of

Plural Economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 9.

ISBN 0-521-54262-6. Cited in Vicker, Adrian (2005). A History of Modern

Indonesia. Cambridge University Press. p. 9. ISBN 0-521-54262-6.

47. ^ Beck, Sanderson, (2008) South Asia, 1800-1950 - World Peace

Communications ISBN 0-9792532-3-3, ISBN 978-0-9792532-3-2 - By

1930 more European women had arrived in the colony, and they made up

113,000 out of the 240,000 Europeans.

48. ^ Van Nimwegen, Nico De demografische geschiedenis van Indische

Nederlanders, Report no.64 (Publisher: NIDI, The Hague, 2002) P.36 ISBN

9789070990923

49. ^ Van Nimwegen, Nico (2002). "64" (http://www.nidi.knaw.nl/Content

/NIDI/output/reports/nidi-report-64.pdf). De demografische geschiedenis

van Indische Nederlanders [The demography of the Dutch in the East

Indies]. The Hague: NIDI. p. 35. ISBN 9789070990923.

50. ^ Taylor (2003), p. 238

51. ^ Vickers (2005), p. 9

52. ^ Reid (1974), p. 170, 171

53. ^ Cornelis, Willem, Jan (2008). [[[:id:Vreemde Oosterlingen]] and [1]

(http://www.tongtong.nl/indische-school/contentdownloads

/tjiook_09web.pdf) De Privaatrechterlijke Toestand: Der Vreemde

Oosterlingen Op Java En Madoera ( Don't know how to translate this, the

secret? private? hinterland. Java nd Madoera)]. Bibiliobazaar.

ISBN 978-0-559-23498-9.

54. ^ a b c Taylor (2003), p. 286

55. ^ Taylor (2003), p. 287

56. ^ a b TU Delft Colonial influence remains strong in Indonesia

(http://www.tudelft.nl/live/pagina.jsp?id=890cbbcfa9ce-4ea6-9b38-4fdbecbee3ce&lang=en)

57. ^ Note: In 2010, according to University Ranking by Academic

Performance (URAP), Universitas Indonesia was the best university in

Indonesia.

58. ^ "URAP - University Ranking by Academic Performance"

(http://www.urapcenter.org/2010).

59. ^ Vickers (2005), p. 15

60. ^ R.B. Cribb and A. Kahin, p. 108

61. ^ R.B. Cribb and A. Kahin, p. 140

62. ^ R.B. Cribb and A. Kahin, pp. 87, 295

63. ^ Harry J. Benda, S.L. van der Wal, "De Volksraad en de staatkundige

ontwikkeling van Nederlandsch-Indi: The Peoples Council and the

political development of the Netherlands-Indies." (With an introduction and

survey of the documents in English). (Publisher: J.B. Wolters, Leiden,

1965.)

64. ^ Note: The European legal class was not solely based on race restrictions

and included Dutch people, other Europeans, but also native

Indo-Europeans, Indo-Chinese and indigenous people.

65. ^ Virtual Indies Website, multi media conservation project by Pelita. See:

Raad van Indie. (http://www.virtueelindie.nl

/index.php?pagina=virtueelindie&locatie=7)

66. ^ Note: Adat law communities were formally established throughout the

archipelago e.g. Minangkabau. See: Cribb, R.B., Kahin, p. 140

67. ^ http://alterisk.ru/lj/IndonesiaLegalOverview.pdf

Dutch East Indies - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

11/02/2014 11:19

68. ^ Note: The female 'Boeloe' prison in Semarang, which housed both

European and indigenous women, had separate sleeping rooms with cots

and mosquito nets for elite indigenous women and women in the European

legal class. Sleeping on the floor like the female peasantry was considered

an intolerable aggravation of the legal sanction. See: Baudet, H., Brugmans

I.J. Balans van beleid. Terugblik op de laatste halve eeuw van NederlandsIndi. (Publisher: Van Gorcum, Assen, 1984)

69. ^ Virtual Indies Website, multi media conservation project by Pelita. See:

Gevangenissen. (http://www.virtueelindie.nl

/index.php?pagina=virtueelindie&locatie=7)

70. ^ Baudet, H., Brugmans I.J. Balans van beleid. Terugblik op de laatste

halve eeuw van Nederlands-Indi. (Publisher: Van Gorcum, Assen, 1984)

P.76, 121, 130

71. ^ Cribb, R.B., Kahin, pp. 140 & 405

72. ^ http://www.indonesianhistory.info/pages/chapter-4.html, sourced from

Cribb, R. B (2010), Digital atlas of indonesian history, Nias,

ISBN 978-87-91114-66-3 from the earlier volume Cribb, R. B; Nordic

Institute of Asian Studies (2000), Historical atlas of Indonesia, Curzon ;

Singapore : New Asian Library, ISBN 978-0-7007-0985-4

73. ^ Blakely, Allison (2001). Blacks in the Dutch World: The Evolution of

Racial Imagery in a Modern Society. Indiana University Press. p. 15 ISBN

0-253-31191-8

74. ^ Cribb, R.B. (2004) Historical dictionary of Indonesia. Scarecrow Press,

Lanham, USA.ISBN 0 8108 4935 6, p. 221 [2] (http://books.google.co.uk

/books?id=SawyrExg75cC&dq=number+of+javanese+in+KNIL&

source=gbs_navlinks_s); [Note: The KNIL statistics of 1939 show at least

13,500 Javanese and Sundanese under arms compared to 4,000 Ambonese

soldiers]. Source: Netherlands Ministry of Defense (http://www.defensie.nl

/nimh/geschiedenis/tijdbalk/1814-1914_nederlands-indi/).

75. ^ Nicholas Tarling, ed. (1992). The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia:

Volume 2, the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries (http://books.google.com

/books?id=pBfsaw64rjMC&pg=PA104). Cambridge U.P. p. 104.

ISBN 9780521355063.

76. ^ Petra Groen, "Colonial warfare and military ethics in the Netherlands

East Indies, 18161941," Journal of Genocide Research (2012) 14#3 pp

277-296

77. ^ Willems, Wim Sporen van een Indisch verleden (1600-1942). (COMT,

Leiden, 1994). Chapter I, P.32-33 ISBN 90-71042-44-8

78. ^ Willems, Wim Sporen van een Indisch verleden (1600-1942). (COMT,

Leiden, 1994). Chapter I, P.32-36 ISBN 90-71042-44-8

79. ^ John Sydenham Furnivall, Colonial Policy and Practice: A Comparative

Study of Burma and Netherlands India (Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 1948), 236.

80. ^ Klemen, L (1999-2000). "Dutch East Indies 1941-1942"