Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Student - Driven Art

Hochgeladen von

api-252860425Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Student - Driven Art

Hochgeladen von

api-252860425Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

even years ago our high school added a student-driven art course. Art and Ideas, to our curriculum.

As a high school art teacher, I wanted an art class that would attract all students, not primarily just the artistically gifted. That class assumed five goals: To study the aits of oilier culliires To connect art to other curricular areas To attract the nontraditional art students To promote a student driven cuniculnm To employ several assessment methods The structure and functioning mechanics of this course are described in the September 2001 issue of.4r/ Educaiion in "Ait aiid Ideas: Reaching Nontraditional Art Students" (Andrews, 2001). When we introduced Art. and Ideas, our focus was to create a classroom environmeni ihal would promote greater student input into learning and the choice of ai1 projects. In this inclusive environment, as students made choices for their art projects, Ihey als(j became more responsible for their learning as well as more energetic, enthusiastic students, hi addition, unjuiticipated benefits or outgrowths also resulted. Five of Ihese will be discussed. The purpose of this article is to streugthen \lsiial arl in the classroom by empowering the student.

BY

BARBARA

HENRIKSEN

A N D R E W S

Student writing and reflection are a m^jor component of IhiscUiss; therefore, excerpts from their writings mv included throughout this article. All student quotations are from reflective papei-s written between 2001 and 2004. Due to the very personal infonuatioii that is often shared, iast names of students willuot be used.

and

Creativity

in the Classroom

Visual Connections to Other Curricular Areas

The first unanticipated outgrowth was st udents tnily seeing the connections between art iuid other curricular areas. As we studied art history, c'ulture, and the many reasons artists have for creating art, students better grasped the relationship between ait and the world around them.

The Student-Driven Art Course

JULY

2005

/ ART EDUCATIO

"By doing a community works project, we are swerving from the path so often stereotypically given to teenagers. We believe even the smallest artistic addition to an office or building can produce a profound effect on the life and outlook of people in our community. And because of this, we decided to help."

Eric Jensen, author of the ASCD hook Arts ivith theBmin in Mind, argues that the arts should be a m^or discipline in the schools"one worth making everybody study and leam." Not only can the arts be a powerful sohit ion for helping educators reach a wide range of learners, they also "enhance the process of learning" by developing a student's "integrated sensory, attentional, cognitive, emotional, and motor capacities," writes Jensen. Such brain systems are the driving forces behind all other learning, he adds. (Allen, 2004, p. 2) Through the development of classroom discussions, students identified the relationships between art and other cunicular areas. Some elected to visually show these connections as their studio art project. After receiving permission from the administration, they began painting reproductions of the masters in the hallways of our high school. Depicting work by M. C. Escher and Cubist artists in the math wing and paintings by Diego Rivera and Joan Miro in the Spanish wing were obvious choices. Students determined that a reproduction of The Great Wave of Kanagawa by Katsushika Hokusai should be placed in the science wing. As students discussed the American Romantic authors being studied in literature, Moonlil Landscape by the Romantic painter Washington Alston was a perfect

match for the English area. Likewise, work by Walter Gropius was an excellent example of art completed during the Federal Art. Project, and a reproduction w;is placed in the history hallway. Within 2 years, every curricular area had recreated masterpieces on the walls related to their subject. Students were eager to share their insights of where to best place a painting, as well as to literally leave their mai'k on the school. This has resulted in pride on the part of the student artists. As Aileen wrote. By painting Chagall's Paris Tftmugh My Window on the wall, many conversations that tyjiically would never come up were started. We were able to discuss certain aspects of it, share our own opinions, and also listen to other viewpoints. Moving outside our usual classroom presented us with an opportunity to make masterjiieces an everyday expression and conversation starter. Teachers in other cunicular areas now approach the art department witli ideas and suggestions for additional student work. These paintings also serve as writing prompts. English teachers have taken tlieir students on an "Ait Walk," spending 5 to 10 minutes at selected masterpieces. Upon returning to the classroom, students write a short story inspired by one of the re-created masterpieces.

ART

EDUCATION

/ JULY

2005

work displayed in the neighborhood and aie able to include the project in their resumes. For example, Kyle's design was selected by the diabetes awareness program at our local hospital and his new logo for the Indiana Central Association of Diabetes Educators is displayed on their shirts and stationery The school receives positive accolades from the community, and the art department grows as the businesses often thank us witli monetary gifts in addition to their charitable donation. Our area hardware and paint stores now donate or sell at greatly reduced price, gallons of "mis-mixed" paint. Thus, our art department is partly funded by the business community. We did not intend to go into business, but business did choose to embrace our art department.

Classroom Partnering with the Community

A second, unintended derivative of a student-driveu curriculum was the opportmiity to partner with the business world. After a few months of painting on our school walls, students wanted to expand their work into the community. StudeiiLs, not the teaciier, locate a business or civicorganization to paint, .such as credit unions, day care centers, restaurants, and volunteer fire stations. Students must initiate the discussion. After designing an appropriate logo or mural, they present their idea to the business representative. Upon approval, they execute the art project. After completion, the business

makes a donation to a charity as a thank you for the student work. In addition, our local newspaper publishes aji article with photographs of the work and the name of the charity to which the donation haa been made. The students are excited to see their artwork in the "real world." The support, in return, from the couiuuinity is energizing. Businesses now contact the high school to become involved with the ail departtnent. Small businesses that could not afford to hire a design team now partner with our students. This alliance has benefited all. The business owner receives a newly created logo or nuu;d. The students have their graphic design

Our students have gained practical, conunercial ait experience and have been personally energized by the opportunity to visually make a difference. As students Jill and Amanda wrote. By doing a community works project, we are swerving from the [)ath so often stereotyjjically given to teenagers. We believe even the smallest artistic addition to an office or building can jjroduce a profound effect ou the life and outlook of people in our community. And because of this, we decided to help.

JULV

2005

/ ART

EDUCAT

Meaningful Classroom Opportunities

A third outgrowth was truly meaJiingful learning experiences for the sludenls. As students take responsibility for their art projects, they become personally vested in their education. "When students have a voice and a degree of choice, and when they are asked to consider how their learning should progress, they are likely to understand the import.ance of the learning process" (Daniels & Bizar, cited in Milbrandt, Felts, & Riclianls, 2004, p. 20). Daniels and Bizar (1998) went on to write, "Slnicturing purpose ;md meaning should be at the heart of artistic activity" (P-20).

students are engaged in artmaking, art planning, and art reflection. They are the instigators of their art curriculum; not passive bodies waiting for instruction.

Each student has a different background and reason for enrolling in a student-driven art class. One young lady wrot.e, 1 had a lot of problems at home and in my head. These problems led me to bulimia and depression. No matter what other people took from me mentally or physically, I always had my art to hold onto. I never tmsted people so I needed something; that something was art. Another student shared his reasons for taking the class, I'm kind of a goof ball, which I'm sure you know, but 1 still dream. Without classes like this one, students would not be able to have the chance to dream. Tliis class opens your mind to endless possibilities, and that's what keeps us striving to do our best, dreams. These young people have become passionate art students. Their desire to learn more, read more, aiid create more is contagious. After a couple of months in the class, another student concluded, I realized that the projects I made in Art and Ideas were able to be used for things outside class that actually had a purjjose. I think that is why this class has become one of the few that actually has a purpose for me being in school.

students working on different projects during same class period.

ART

EDUCATION

/ JULY

2005

Shift in Teacher and Student Roles

A fourth derivative of this class stnicture was a shift in roles. My role as ail art teacher in the classroom has expanded. F*reviously, I ladled out all the instniction. Now, students share in the teaching of studio techniques and processes. Our expert water colorist shares knowledge with a novice, our expert cerajnist assists those new to the wheel, and so forth. I oversee the total learning experience, from students painting in the halls to proper classroom operating procedures. I set the tone and establish expectations, functioning more like an art orchestra conductor. Students are now often overheard saying, "Wow, I like how you threw that pot. I want to learn how to do that." In addition, students seem to li.slen attentively to their friends and classmates. As Ryan explained, "I think that learning from our peers is more efficient because we can relate to them better than with teachers." lyier added, "I leani better from a friend because they're more on my level. I can understand them betterand I'd listen to them more." Students are engaged in artmaking, art planning, and art reflection. They are the instigators of their art cuiTif ulum; not passive bodies waiting for instruction. As Katie concluded in her paper, Tliis class has shown me a different side of things also. Weird things happen in here that baffle my mind. People care about art; they have long conversations about it, and to me, that's different. Just recently I had a conversation with my friends, in art class, about all the meanings behind particular- art pieces! Who has those kinds of conversations? This arrangement fosters greater interaction among the student artists, brings more ideas inio the art room, and creates an atmosphere of enthusiasm and creativity.

Shift in Emphasis from the Product to the Idea

This class, Art and Ideas, is not offered with the end product in mind. It is not labeled drawing or painting or ceramics. Rather, it is the idea, the thought process, the disciplined creative effort that is the starting point. As Eliza Pitri (2003) writes, "The process of artmaking is more iniportiint than the produt t because it could and should involve thinking and I)roblem solving" (p. 23). Jessica expressed (he difference between a conventional art class and a student-driven art class. The typical art class in high school was a teacher standing in front of a group of students waiting for directions. Guidelines ai'e always placed on the project and what and how the student can go about creating it. You had to (k) it the teacher's way. In a student-driven art room, several ideas are activated simultaneously, as evidenced by the different media that are explored during one class period. Tliis works wonderfully for high school

students, who also want the opportunity to express their individualism. As Josh wrote, In a regular art room all the kids are working on the same thing. No two people are the same so why would you chain their hands and minds together so that all you are doing is limiting their abilities. This class is like taking a lake that has been dammed up for hundreds of years and letting dowii the flood gates. One can only sit back and watch the water scrape and become different after so long. See schools teach kids art, but they have to also let kids create art, because art is the handwriting of the soul.

"This class is like taking a lake that has been dammed up for hundreds of years and letting down the flood gates."

JULY

2005

/ ART

EDUCAT

As students take more responsibility for their art cuniculum t hey become more aw;ire of their learning styles and potential. Ross wrote, "In olher ait courses you do what they want and what they plan. In this class you have to think." Jason added, "I don't learn from a teacher lecturing. I leani by discovering." For some students, art is a tool to better understand culture. Upon completing a reproduction of Diego Rivera's Tlir Flower Carrier in the Spanish language area of the school, Gilberto concluded, I can relate to the sombrero hats and the tyi)e of clothing used in my painting. Those things are a part of my background, my heritage, and most importantly, me. If I go back in my memoiy to Honduras I can remember baskets woven as the one which carries the flowers. I can also relate to the darkness of the skin of the people. The elder, short woman supporting the basket reminds me of my grandma. I took this class to broaden my mind and artistic talents. It turns out that in doing so. I touched on things that already pertained to me. I learned new things by involving some old things.

Conclusion

A st udent-driven curriculum is more Ihan a choice about art project options; it is a responsibility. Students leach, discuss, seek out job sites, and create Iheir ait curriculum; they are active learners, not passive. Their efforts and enthusiasm promote our art program. The teacher is no longer the sole individual championing the arts. Each student actively i)articipates in this opportunity. As we partner with the business community, they support, rather than challenge our art programs. Wlien we nurtiue students' passion forthe visual arts, we promote a futui'e generation of ait makers and art supporters. Barhara HniriLsen Audmvs is an art leacher al New Falesline High School, NeivPalestine, Indiana. E-mail: handreivs@neurpalkl2.in.us

SUGGESTED

RESOURCES

Corttnes, R. (U)95, ,lannaiy). Beyond the three R's: student achievement through the arts. TcdcliiiHi ill and Ilirniiffh Ihfarls.six'ciiil rrport. (ietty Center tor Ihe Education of the Alls nnii Natioiuil Conference, W;Lsliinf!1.on, UC. Diiim, P. C. (1995). Creating nmiculum hi tui. Resl(m,VA.: National Art Education Association. Eisner, E. W. (1997, November). Arts educntUm J'ora chdiifiiiif) iroiid. Alexandria, VA.: A.'jsociat ion for Supervision and Curriculum t)evelopnient. Eisner, E. W. (1997). EdiivaIhig artistic irisioii. New York; Macmilliin. Peeno, L. N. (Ed.). (\m^3).Ad<ipl<iti<ym(>fl.he national rifiiinl mis sl(iiiil(ird.s: NntioiKtl, sidtr, and dislhcl r.raniplcs. Restoii, VA: National An Education A.s.sociation. Stiggins. R. J. (Mi7). Sliidenl-ccntinvd classroom assessment (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill, Prentice Hall.

NOTE

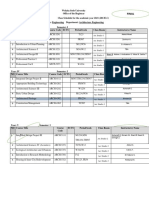

Photographs show New F'alestine High School si udents and their work throughout the school and community.

REFERENCES

Allen, R. (20114, Spring). In tlic front row, the arts give students a lifkt-t to learning. ASCD Curriciilimt Viidalr. Atexiiiidria, VA.: Association for SupeiTision and Cuniciiliint Dt'Vflopment. Andrews, B. H. fawi}. Art and ideas: reaching iicnUraditional an studenls. Miibrandt, M., Felts, J., Richards, B., & Abghari, N. (2004). Teachinji to learn: A conslriictivisl approach to shared community. Ayt FAlmtiliou, .')7(5 Pitri, E. (2003). ("onceplual problem solving during artistic representation./I i7 />(4), 19-23.

ART

EDUCATION

/ J U L Y

2005

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Persuasive Writing RubricDokument2 SeitenPersuasive Writing Rubricapi-252860425Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- 3-12 6+1 & CC AlignedDokument15 Seiten3-12 6+1 & CC Alignedapi-252860425Noch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- 6+1 Traits, Engage Ny, Developmental Continuum ConnectionsDokument1 Seite6+1 Traits, Engage Ny, Developmental Continuum Connectionsapi-252860425Noch keine Bewertungen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Belinda BlueDokument1 SeiteBelinda Blueapi-252860425Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Unit Persuasivewriting TransfertechniquesDokument1 SeiteUnit Persuasivewriting Transfertechniquesapi-252860425Noch keine Bewertungen

- T ChartDokument1 SeiteT Chartapi-252860425Noch keine Bewertungen

- Unit Persuasivewriting PicsymbslogDokument1 SeiteUnit Persuasivewriting Picsymbslogapi-252860425Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- RWT Persuasion MapDokument1 SeiteRWT Persuasion Mapapi-252860425Noch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- 5 Senses GoDokument1 Seite5 Senses Goapi-252860425Noch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Writetolearn FinalposterDokument1 SeiteWritetolearn Finalposterapi-252860425Noch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Narrative EssayDokument1 SeiteNarrative Essayapi-252860425Noch keine Bewertungen

- Persuasive WritingDokument8 SeitenPersuasive Writingapi-252860425100% (1)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Show, Don't Tell Sentences: Trait or EmotionDokument1 SeiteShow, Don't Tell Sentences: Trait or Emotionapi-252860425Noch keine Bewertungen

- Essay Writing For Everyone, ScottDokument9 SeitenEssay Writing For Everyone, Scottapi-252860425Noch keine Bewertungen

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Revise Edit PosterDokument1 SeiteRevise Edit Posterapi-252860425Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Argument OutlineDokument1 SeiteArgument Outlineapi-252860425Noch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Content RatingsDokument17 SeitenContent Ratingsapi-252860425Noch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Make A PlanDokument1 SeiteMake A Planapi-252860425Noch keine Bewertungen

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Digital Media WritingDokument10 SeitenDigital Media Writingapi-252860425Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Map It Out: Beginning Middle EndDokument1 SeiteMap It Out: Beginning Middle Endapi-252860425Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Nifty Narrative: Purpose Skills / StandardsDokument2 SeitenNifty Narrative: Purpose Skills / Standardsapi-252860425Noch keine Bewertungen

- What I Treasure Most: MaterialsDokument5 SeitenWhat I Treasure Most: Materialsapi-252860425Noch keine Bewertungen

- Title: Topic: Purpose:: First, Next, LastDokument1 SeiteTitle: Topic: Purpose:: First, Next, Lastapi-252860425Noch keine Bewertungen

- Publishing JourneyDokument1 SeitePublishing Journeyapi-252860425Noch keine Bewertungen

- Personal Narrative Graphic Organizer SnapshotDokument1 SeitePersonal Narrative Graphic Organizer Snapshotapi-252860425Noch keine Bewertungen

- Articles: Practice Set - 1Dokument4 SeitenArticles: Practice Set - 1Akshay MishraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gre Analogies: A Racket Is Used To Play TennisDokument9 SeitenGre Analogies: A Racket Is Used To Play TennisaslamzohaibNoch keine Bewertungen

- Report On The Physical Count of Inventories CLASSROOM INVENTORY (Pricipal's Office)Dokument29 SeitenReport On The Physical Count of Inventories CLASSROOM INVENTORY (Pricipal's Office)Evelyn SarmientoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Compose - User - Guide SmartmusicDokument20 SeitenCompose - User - Guide SmartmusicJesse SchwartzNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Method Statement For Columns2Dokument5 SeitenMethod Statement For Columns2Jasmine TsoNoch keine Bewertungen

- American History XDokument110 SeitenAmerican History XNick LaurNoch keine Bewertungen

- BAGL 6-1 Watt PDFDokument12 SeitenBAGL 6-1 Watt PDFguillermoisedetNoch keine Bewertungen

- Five Childrewn and ItDokument3 SeitenFive Childrewn and Itrosaroncero100% (2)

- Jan 2014 Sample SaleDokument6 SeitenJan 2014 Sample Saleposh925sterlingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Checkout Counter Number Three #3Dokument31 SeitenCheckout Counter Number Three #3Samantha Marie VargasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hegel Philosophy Application On Aeschylus AgamemnonDokument5 SeitenHegel Philosophy Application On Aeschylus AgamemnonMuhammad MohsinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jose Rizal: A Biographical SketchDokument3 SeitenJose Rizal: A Biographical SketchVin CentNoch keine Bewertungen

- DJ Naves BioDokument1 SeiteDJ Naves BioTim Mwita JustinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Caravanning Australia v14#1Dokument196 SeitenCaravanning Australia v14#1Executive MediaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Panda Bear Earflap/Beanie Hat - : Sizes Newborn To AdultDokument24 SeitenPanda Bear Earflap/Beanie Hat - : Sizes Newborn To AdultNevenka Penelopa Simic100% (3)

- Hyperdesmo Polyurea 2K HCDokument3 SeitenHyperdesmo Polyurea 2K HCmeena nachiyarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Architectural Photography Presentation - Brett Ryan StudiosDokument113 SeitenArchitectural Photography Presentation - Brett Ryan StudiosBrett Ryan Studios100% (2)

- Features/Principles of Indian EthosDokument16 SeitenFeatures/Principles of Indian EthosSIDDHANT TYAGI100% (1)

- Arc 2013 1st Sem Class Schedule NEW 1Dokument2 SeitenArc 2013 1st Sem Class Schedule NEW 1Ye Geter Lig NegnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Escola Secundária Teixeira de Sousa English Worksheet Name: Number: ClassDokument2 SeitenEscola Secundária Teixeira de Sousa English Worksheet Name: Number: ClassKleber MonteiroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Language Unseen PoetryDokument2 SeitenLanguage Unseen PoetryWitchingDread10Noch keine Bewertungen

- Article CssDokument3 SeitenArticle Cssshalini0220Noch keine Bewertungen

- Sad I Ams Module Lit Form IDokument38 SeitenSad I Ams Module Lit Form ImaripanlNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Play Single Notes On The HarmonicaDokument19 SeitenHow To Play Single Notes On The HarmonicaxiaoboshiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Toomer, John Selden (Review)Dokument2 SeitenToomer, John Selden (Review)Ariel HessayonNoch keine Bewertungen

- PhonicsMonsterBook2 PDFDokument61 SeitenPhonicsMonsterBook2 PDFPaulo Barros80% (5)

- Slovenian Urban Landscape Under Socialism 1969-1982Dokument16 SeitenSlovenian Urban Landscape Under Socialism 1969-1982SlovenianStudyReferences100% (1)

- The Legend of RiceDokument6 SeitenThe Legend of RiceMargaux Cadag100% (1)

- How We Came To Live Here PDFDokument46 SeitenHow We Came To Live Here PDFJ.B. BuiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Inventor Project Frame Generator Guide enDokument16 SeitenInventor Project Frame Generator Guide enHajrah SitiNoch keine Bewertungen