Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Patologias

Hochgeladen von

Jaime Jesús Segura GranadosOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Patologias

Hochgeladen von

Jaime Jesús Segura GranadosCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

"#$%&'#(%) *% +,-)$&.//'0- 1,-('-%2 3$$45667#$%&/,-)$&.

//8&%9')$#)8/)'/8%)

!"#$%&'()* "&,-)".* /&&,-),. 0"#$%&'(-)

AuLor(es)

AuLhor(s):

Lerma, C., Mas, ., Cll, L., vercher, !., enalver, M.!.

1lLulo (orlglnal, LS):

1lLle (orlglnal, LS):

aLologla de maLerlales de consLruccln en edlflclos hlsLrlcos. 8elacln

enLre ensayos de laboraLorlo y Lermografla lnfrarro[a

1lLulo (orlglnal, Ln):

1lLle (orlglnal, Ln):

aLhology of 8ulldlng MaLerlals ln PlsLorlc 8ulldlngs. 8elaLlonshlp 8eLween

LaboraLory 1esLlng and lnfrared 1hermography

ldloma:

Language:

Lspanol e lngles (blllngue)

Spanlsh and Lngllsh (blllngual)

uCl: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

lecha de recepcln:

8ecelved daLe:

13/12/2012

lecha de acepLacln:

AccepLed daLe:

12/03/2013

ubllcacln !"#$"%:

ubllshed onllne:

01/04/2013

1$,., &()"' ,%), "')2&$3* &*0*: 4*$ 0"5 &(), )6(% "')(&3, "%:

Lerma, C., Mas, ., Cll, L., vercher, !., enalver, M.!.: aLologla de maLerlales de consLruccln

en edlflclos hlsLrlcos. 8elacln enLre ensayos de laboraLorlo y Lermografla lnfrarro[a".

&'(%)$'#%* ,% -!"*().//$0" (2013) [en llnea], manuscrlLo acepLado. dol:

10.3989/mc.2013.06612

Lerma, C., Mas, ., Cll, L., vercher, !., enalver, M.!.: aLhology of 8ulldlng MaLerlals ln

PlsLorlc 8ulldlngs. 8elaLlonshlp 8eLween LaboraLory 1esLlng and lnfrared 1hermography".

&'(%)$'#%* ,% -!"*().//$0" (2013) [onllne], accepLed manuscrlpL. dol:

10.3989/mc.2013.06612

789/: LsLe documenLo es un arLlculo lnedlLo

que ha sldo revlsado y acepLado para su

publlcacln. Como un servlclo a sus auLores y

lecLores, &'(%)$'#%* ,% -!"*().//$0"

proporclona esLa edlcln prellmlnar !"#$"%. Ll

manuscrlLo puede sufrlr alLeraclones Lras la

edlcln y correccln de pruebas, anLes de su

publlcacln deflnlLlva. Los poslbles camblos no

afecLarn en nlngun caso a la lnformacln

conLenlda en esLa ho[a, nl a lo esenclal del

conLenldo del arLlculo.

789:: 1hls documenL ls a revlewed manuscrlpL

accepLed for publlcaLlon. As a servlce Lo our

auLhors and readers, &'(%)$'#%* ,%

-!"*().//$0" provldes Lhls early onllne verslon.

1he manuscrlpL may undergo some changes

afLer revlew of Lhe resulLlng proof before lL ls

publlshed ln lLs nal form. Any posslble change

wlll noL affecL Lo Lhe lnformaLlon provlded ln

Lhls cover sheeL, or Lo Lhe essenLlal conLenL of

Lhe arLlcle.

Materiales de Construccin

Accepted manuscript

2013

ISSN: 0465-2746

eISSN: 1988-3226

doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

Patologa de materiales de construccin en edificios histricos. Relacin entre

ensayos de laboratorio y termografa infrarroja

Pathology of Building Materials in Historic Buildings. Relationship Between

Laboratory Testing and Infrared Thermography

C. Lerma

a,

*, . Mas

a

, E. Gil

a

, J. Vercher

a

and M. J. Pealver

a

a

Universitat Politcnica de Valncia. (Valencia, Espaa).

*Persona de contacto/Corresponding author: clerma@csa.upv.es.

Recibido/Submitted: 13/12/2012

Aceptado/Accepted: 12/03/2013

Publicado online/Published online: 01/04/2013

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

2

RESUMEN

Patologa de materiales de construccin en edificios histricos. Relacin entre ensayos de

laboratorio y termografa infrarroja

El estudio de edificios histricos requiere un anlisis de la patologa de los materiales de

construccin empleados para poder definir su estado de conservacin. Habitualmente nos

encontramos con humedades por capilaridad, cristalizacin de sales o diferencias de densidad

por deterioro. En ocasiones esto se lleva a cabo mediante ensayos destructivos que nos

determinan las caractersticas fsicas y qumicas de los materiales, pero que resultan

desfavorables respecto a la integridad del edificio, y en ocasiones resulta complejo llevarlos a

cabo. Este trabajo presenta una tcnica para analizar la patologa existente mediante el empleo

de termografa infrarroja con la ventaja de poder diagnosticar zonas de difcil acceso en los

edificios. Para validar este estudio se han comparado los resultados obtenidos mediante esta

tcnica con los alcanzados en el laboratorio. De esta forma podemos extrapolar la metodologa

empleada a otros edificios y materiales.

PALABRASCLAVE: Caliza; deterioro; propiedades fsicas; anlisis trmico.

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

3

SUMMARY

Pathology of Building Materials in Historic Buildings. Relationship Between Laboratory

Testing and Infrared Thermography

Study of historic buildings requires a pathology analysis of the construction materials used in

order to define their conservation state. Usually we can find capillary moisture, salt crystalli-

zation or density differences by deterioration. Sometimes this issue is carried out by destructive

testing which determine materials physical and chemical characteristics. However, they are

unfavorable regarding the buildings integrity, and they are sometimes difficult to implement.

This paper presents a technique using infrared thermography to analyze the existing pathology

and has the advantage of being able to diagnose inaccessible areas in buildings. The results

obtained by this technique have been compared with those obtained in the laboratory, in order to

validate this study and thus to extrapolate the methodology to other buildings and materials.

KEYWORDS: Limestone; decay; physical properties; thermal analysis.

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

4

For English text go to page 17

1. INTRODUCCIN

Las medidas de conservacin apropiadas al edificio objeto de estudio solo se pueden

planificar y ejecutar en base a un diagnstico preciso de los daos, que suministre un

conocimiento suficiente y fiable acerca de los materiales empleados, as como los factores,

procesos y estado de deterioro (1). Debemos tener mucha precaucin a la hora de intervenir en

un edificio histrico, por lo que la utilizacin de tcnicas no destructivas como la termografa

infrarroja facilitan el estudio y la comprensin de los materiales sin necesidad de perjudicar el

inmueble.

En este edificio, al igual que en la mayora de edificios histricos se han usado diferentes

materiales de construccin. Esta diversidad se debe a consideraciones arquitectnicas,

trabajabilidad constructiva o artstica, proximidad y facilidades de explotacin de las canteras...

El estado del deterioro de un monumento se caracteriza por el tipo, la intensidad y la extensin

de los daos.

La mayora de las imgenes que se muestran hacen referencia a los muros exteriores del

Colegio de Corpus Christi de Valencia, compuestos por un zcalo perimetral de piedra y un

alzado de tapia valenciana (tapial y ladrillos) de 80 cm de espesor.

Existen varias modalidades (9) en el uso de la tecnologa infrarroja, aunque las ms

habituales son la termografa activa, que consiste en calentar la muestra artificialmente, y la

termografa pasiva, donde el material o cerramiento se calienta por el efecto natural de la

energa solar. Cuando estudiamos superficies de grandes dimensiones, como las fachadas de los

edificios, especialmente si estn situados en un entorno urbano donde las calles son estrechas,

consideramos que la opcin ms viable es la termografa pasiva por ser la que ms se ajusta a la

situacin real.

Respecto a la tcnica empleada de termografa infrarroja, se debe sealar que en estudios

anteriores se ha relacionado la termografa con algunos defectos en los materiales ptreos

interpretando las imgenes termogrficas desde un punto de vista grfico en los distintos puntos

del muro (3). Aquellas reas donde se producen discontinuidades trmicas corresponden a

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

5

puntos con defectos en el material. Sin embargo, aquellos puntos con una temperatura similar

representan su inercia trmica, la tendencia del elemento a resistir cambios trmicos, y

dependen de las caractersticas del material, la humedad y los daos que poseen (4). Se ha

empleado tambin la termografa para detectar zonas hmedas mediante un anlisis

multitemporal (5). Nuestra aportacin se centra en relacionar diversos ensayos de labora-torio y

anlisis del material con las imgenes tomadas con la cmara termogrfica, con el objetivo de

corroborar los resultados obtenidos por estas dos vas.

Para la realizacin de este estudio se ha empleado una cmara FLIR B335 que genera

imgenes termogrficas a una resolucin de 320 x 240 pxeles, tiene un intervalo de

temperaturas entre -20 y +120 C y una precisin menor a 50 mK NETD. El tratamiento

posterior de las imgenes termogrficas se ha realizado con el software FLIR QuickReport, con

el que podemos variar la paleta de colores, el intervalo de temperaturas, la distancia al

cerramiento, calcular la temperatura mxima, mnima y media de las zonas que se desee

estudiar, as como exportar en formato Excel la temperatura de cada pxel de la imagen.

2. METODOLOGA

El procedimiento que hemos llevado a cabo representa un anlisis adecuado de las

imgenes termogrficas tomadas del edificio. Contrastamos los resultados obtenidos de dichas

imgenes con los ensayos de laboratorio realizados en los materiales.

Los materiales analizados en este estudio son piedras calizas tradicionales de la Comunidad

Valenciana, como son la piedra de Godella y la piedra de Ribarroja, ampliamente usadas

durante siglos en la ciudad de Valencia y la piedra de Bateig Azul empleada en la actualidad.

Los ensayos de laboratorio se han realizado sobre 50 probetas cuyos resultados han

aportado las caractersticas propias del material, como su densidad, porosidad, composicin

qumica, etc. y la termografa infrarroja nos muestra el comportamiento trmico de los

materiales. El peso de las muestras empleadas en laboratorio se ha registrado con una balanza de

precisin (0,01 g).

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

6

2.1. Termografa infrarroja

La posibilidad de visualizar claramente los defectos de un material depende de la diferencia

entre las caractersticas trmicas de los materiales y la falta de homogeneidad existente (6),

donde el patrn trmico del material depende en gran medida de sus caractersticas (difusin

trmica, porosidad, densidad). Para los materiales de construccin habituales, el valor de la

emisividad es mayor de 90%, en nuestro caso hemos tomado el valor por defecto de 0,95 por lo

que los resultados obtenidos en la medicin termogrfica los consideramos fiables (7).

Se ha empleado termografa pasiva tanto en los ensayos realizados in situ como en los

llevados a cabo en laboratorio. De acuerdo con Caas (8), en ausencia de sol los datos obtenidos

de la termografa son muy precisos, tanto para materiales cermicos, ptreos, como adobe. Esto

es debido a que si los rayos solares inciden sobre las fachadas la respuesta trmica del material

se ve alterada. Las imgenes termogrficas que se muestran estn tomadas antes del amanecer

cuando, adems, se alcanza la mnima temperatura del material y nos permite cometer menos

errores al comparar datos e imgenes.

La diferencia de temperatura entre distintos materiales es debida en gran medida a su

densidad y calor especfico y en concreto, a su inercia trmica. La piedra dispone de una gran

capacidad de almacenar energa y requiere ms tiempo para calentarse o enfriarse que otros

materiales como el ladrillo.

Hemos relacionado las imgenes termogrficas con algunas de las propiedades de los

materiales ptreos, considerando aquellas que estn ms vinculadas con el estado de deterioro

del edificio por tratar los mecanismos de circulacin del agua en medios porosos.

Los materiales de construccin son medios porosos y pueden deteriorarse a travs de la

entrada de humedad producindose la degradacin del material, la disolucin de los

compuestos, la migracin de la sal y su cristalizacin o cambios volumtricos incluyendo

hinchazn, grietas y desprendimientos (2).

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

7

2.2. Descripcin de los ensayos

Capilaridad

Los muros de los edificios estn en contacto con el terreno hmedo. El agua asciende a

travs de ellos gracias a las fuerzas capilares al mismo tiempo que se produce el secado de los

muros por efecto de la evaporacin a travs de sus superficies. Normalmente se produce un

equilibrio entre los dos fenmenos generando un perfil o frente de ascensin capilar.

En el proceso de secado se pueden distinguir dos etapas: Una primera corresponde a la

evaporacin de agua de la superficie y depende de las fuerzas capilares y de la naturaleza de la

solucin, siendo lineal en funcin del tiempo (13). La segunda etapa tiene un ritmo mucho ms

lento de evaporacin y corresponde con la difusin del vapor de agua a travs del medio poroso

hacia la superficie (14,15).

La frmula de ascensin capilar (16):

H = 2 ! cos " / (r # g) [1]

Donde, !: tensin superficial, ": ngulo de contacto, r: radio capilar, #: densidad del

lquido, g: gravedad.

La frmula del equilibrio (17) entre ascensin capilar y evaporacin:

h = S (b / (2 e "w)

1/2

[2]

Donde, h: altura capilar de equilibrio, S: capacidad de absorcin, b: espesor del muro, e:

ratio de evaporacin por unidad de rea en la superficie hmeda, "w: contenido de humedad en

la regin hmeda (volumen de agua por unidad de volumen de material).

Para aplicar la ecuacin [2] tomamos los siguientes datos (17): La capacidad de absorcin

S de las calizas se mueve en el rango (0,5-1,5) mm/min

1/2

, por lo que escogemos como valor

medio 1,0 mm/min

1/2

. La fraccin de volumen de porosidad f es generalmente y de forma

aproximada 0,25, sabiendo que "w = 0,85f, tomamos "w= 0,2. Tomamos como espesor del

muro 800 mm. Para la tasa de evaporacin, asumimos el valor de e = 0,004 mm/min (una tasa 4

veces mayor que el promedio de la evaporacin potencial anual en Reino Unido). Se desprecia

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

8

la accin de la gravedad. De esta manera obtenemos una altura de equilibrio h = 0,71 m. Esta

medida terica nos da una referencia respecto al nivel real que se alcanza en cada momento,

pues el equilibrio es variable en funcin de las condiciones climticas.

El zcalo perimetral de piedra tiene una altura entre 0,5 y 1,5 m, habr zonas donde el

frente de ascensin capilar alcanzar el muro de tapia valenciana (Figura 1).

Los ensayos realizados en el laboratorio se han basado en la norma UNE-EN 1925:1999:

Mtodos de ensayo para piedra natural. Determinacin del coeficiente de absorcin de agua

por capilaridad, la cual nos especifica un mtodo para determinar el coeficiente de absorcin

de agua por capilaridad de la piedra natural.

Segn esta norma, los resultados deben expresarse en un grfico (Figura 2) que muestre la

masa absorbida en gramos, dividido por el rea de la base sumergida de la probeta en m

2

, en

funcin de la raz cuadrada del tiempo en segundos. El grfico se debe aproximar por dos lneas

rectas, siendo la pendiente de la recta en el primer tramo el valor de C

1

,

Donde C

1

= (m

i

m

d

) / A et

i

[3]

Con mi: masa para un momento i (g); m

d

: masa seca (g); A: rea de la base sumergida (m

2

);

t

i

: tiempo transcurrido para un momento i (s).

Cristalizacin de sales

La eflorescencia es la cristalizacin de las sales sobre la superficie exterior del material. La

costra es una lmina que se identifica por su dureza, por su color (caso de costras negras) y por

contener productos carbonosos de contaminacin (holln, polvo). La escama es una lmina de

unos pocos milmetros de espesor que se desprende paralelamente a la superficie (21).

Son cristales de sales, como sulfatos de potasio y sodio, habituales en los muros, sobre todo

en los meses de verano. Las sales eflorescentes que forman marcan la posicin de los frentes de

evaporacin, que pueden estar en la superficie de los materiales porosos o con la misma

frecuencia justo por debajo de la superficie dentro de los propios poros.

Identificacin de distintos materiales por sus caractersticas

En el laboratorio hemos comparado dos tipos de muestras calizas de diferente densidad. De

una parte, una muestra de cantera de piedra de Godella (D

a

= 2,55 g/cm

3

) y de otra una muestra

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

9

de piedra de Bateig (D

a

= 2,21 g/cm

3

). El ensayo consisti en mantener las muestras durante

72 horas a 70 5 C, como en otros procedimientos para piedra natural, y registrar con la cmara

termogrfica la prdida de calor en funcin del tiempo (en segundos). Las condiciones

ambientales fueron 24,3 C y 50,3% de humedad relativa.

Deterioro por prdida de densidad

La densidad es la magnitud que expresa la relacin entre la cantidad de masa que

caracteriza el material y su volumen. A mayor densidad, mayor conductividad segn una

funcin exponencial (11). La densidad aparente es una magnitud aplicada a materiales porosos,

los cuales contienen intersticios normalmente de aire, de forma que la densidad total del cuerpo

es menor que la densidad del material poroso si se compactase.

El deterioro por prdida de densidad en el material se ha estudiado previamente para otros

materiales como la madera (12).

En el laboratorio forzamos el deterioro del material hacindolo reaccionar con cido

clorhdrico (HCl al 25%) como describe DOrazio (23). El cido disuelve parcialmente la roca

calcrea y deja los residuos insolubles. Conseguimos as disminuir la densidad aparente de la

muestra.

3. RESULTADOS

En la Tabla 1 se resumen los resultados de los distintos ensayos realizados, tanto in situ

como en laboratorio y, en algunos casos, tericos.

3.1. Capilaridad

In situ

Una vez humedecido un cerramiento, los factores de los que depende el secado del mismo

son: temperatura, humedad relativa, microentorno, porosidad y comportamiento mecnico del

material, duracin de los ciclos humedad/secado (24).

En la Figura 3 se puede ver claramente cmo la curva generada por la ascensin capilar del

agua del subsuelo se refleja en la imagen infrarroja.

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

10

En laboratorio

Los resultados del ensayo de absorcin de agua por capilaridad con muestras de cantera nos

determinan que la absorcin de agua por capilaridad es lenta en funcin del tiempo para este

material ptreo.

En experimentos recientes se ha demostrado que un mayor contenido de humedad supone

una mayor temperatura del material, en comparacin con otras zonas o materiales que

contengan menos humedad (2). En cualquier caso, es evidente el efecto refrigerante de la

evaporacin, pues la temperatura es menor que la ambiental. Adems, las propiedades del

material influyen significativamente en la tasa de evaporacin y, por tanto, en la velocidad con

la que el material cede al ambiente el contenido de humedad.

En los ensayos de laboratorio que hemos llevado a cabo siguiendo la experiencia de Gayo

(22) se observa que una vez humedecido el material comienza la evaporacin del agua,

descendiendo claramente la temperatura de su superficie. Conforme el material pierde esta

humedad tiende a igualar su temperatura con la ambiental.

En el laboratorio hemos llevado a cabo un experimento consistente en observar y registrar

la evolucin en el tiempo del proceso de secado de las muestras (Figura 4). En la Figura 5

vemos termografas en tres etapas del proceso de evaporacin. De las seis muestras, las dos

primeras (izq.) corresponden a la curva (a), las dos siguientes (centro) a la curva (b) y las dos

ltimas (dcha.) a la curva (c). En esta escala de grises, el color negro identifica las temperaturas

menores (hasta 18,7 C) y al color blanco tienden las mayores temperaturas (temperatura

ambiente: 24,3 C). Puede observarse cmo las dos muestras de la derecha, que han

permanecido a temperatura y humedad ambiental, prcticamente ni se detectan. Conforme

avanza el experimento y las otras cuatro muestras pierden humedad van igualando su

temperatura a la ambiental.

En la Figura 6 (izq.) se aprecia el contenido de humedad en porcentaje respecto del peso

seco de seis muestras, mostrndose cmo evoluciona la prdida de peso en funcin del tiempo.

La grfica hace referencia a tres curvas, donde cada curva representa la media de dos muestras,

con distinto grado de humedad que tienden a equilibrarse con la humedad ambiental. La curva

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

11

(a) hace referencia a dos muestras que estuvieron inmersas en agua durante 72 horas, tiempo

suficiente para absorber una mayor masa de agua que las otras muestras; la (b) tan solo 5

minutos; la (c) se dej como referencia con las condiciones ambientales de temperatura (24,3

C) y de humedad (52,9%). Los resultados se han sintetizado en la Tabla 1.

En la Figura 6 (dcha.) tambin se observa la evolucin de la temperatura de dichas

muestras. La curva (a), con mayor porcentaje de humedad requiere ms tiempo para evaporar el

agua absorbida y, por tanto, mantiene una temperatura reducida durante ms tiempo. La curva

(b), al tener menos humedad, la evapora con mayor facilidad y comienza a ascender su

temperatura con ms brevedad. La curva (c) al no variar su contenido de humedad inicial

tambin mantiene constante su temperatura

3.2. Cristalizacin de sales

Terico

En funcin de la velocidad de evaporacin (V

1

) y de la velocidad de migracin del agua

hacia la superficie (V

2

) se produce una morfologa de deterioro distinta debido a la cristalizacin

de las sales en el material (20) (Figura 7).

Las consecuencias de la acumulacin de sal son que las sales pueden bloquear los poros y

los capilares a travs de los cuales el agua se evapora y, por lo tanto, hacer subir el frente

aumentando en consecuencia la humedad (18), reducindose el coeficiente de absorcin capilar

(19). Tambin se generan daos en el material por la constante disolucin y recristalizacin de

ciertas sales que se producen por los cambios de humedad y temperatura. Las sales de sulfato de

sodio depositadas a partir de las aguas subterrneas pueden ser especialmente destructivas para

los edificios y monumentos (25).

In situ

El zcalo de la Figura 8 muestra el ascenso de humedad por capilaridad con una marca

clara. Debemos tener en cuenta que esta fachada nunca recibe la luz solar directamente por estar

orientada a norte. En funcin de la velocidad de evaporacin (V

1

) de esta fachada, la patologa

creada es de eflorescencias. Una imagen termogrfica muestra un conjunto de colores que

representan una temperatura determinada y conocida para cada punto. En esta Figura se

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

12

superpone la grfica de temperaturas del material por el eje que se indica de tal manera que

podemos cuantificar en cada caso las variaciones de temperaturas que se producen en el

paramento.

La fachada que enfrenta al zcalo de la Figura 9 se encuentra orientada a sur y s que recibe

radiacin solar, por lo que la velocidad de evaporacin (V

1

) es mayor que en el caso anterior y

la patologa que se genera es la de escamas, tal y como puede apreciarse en la anterior Figura.

La piedra de Ribarroja situada en las portadas del Colegio de Corpus Christi sufre una

degradacin en planos paralelos que estn generando una serie de desconchados. No todos son

visibles a simple vista, pero la cmara termogrfica los detecta con facilidad (Figura 10). Si la

degradacin que sufre el material ptreo es por exfoliacin tal y como observamos, es decir,

levantamiento y separacin de una o ms lascas o capas (alteradas o no) de espesor uniforme

(varios milmetros), paralelamente entre s y a planos estructurales o de debilidad de la piedra

(10), las lajas que se separan de la matriz de la roca tienen poco espesor y se enfran con gran

rapidez.

Por otro lado, en la Figura 10b vemos en detalle la patologa que afecta a esta piedra. Se

trata de desprendimiento de lajas. Donde no se han desprendido estas lajas, podemos ver la parte

ms superficial de la piedra y donde ya no hay lajas vemos la parte interna de la piedra.

3.3. Identificacin de distintos materiales por sus caractersticas

In situ

En la Figura 11 se pueden ver dos tipos de material ptreo, el zcalo de piedra de Godella

(izq.) y la piedra de Ribarroja (dcha.). La imagen termogrfica est tomada a las 7:12 h, tras casi

12 horas sin soleamiento, siendo la temperatura ambiente de 7,3 C. Los datos analticos se

encuentran en la Tabla 2. Teniendo en cuenta que la piedra de Ribarroja es menos porosa y ms

densa (valores medios), la termografa describe una respuesta trmica un 20% mayor que en la

de Godella (Tabla 1). Una piedra ms densa y ms compacta tiene mayor inercia trmica y

conserva mejor la temperatura.

En laboratorio

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

13

En las Figuras 12 y 13 se observa la prdida de temperatura, siendo la muestra de la

izquierda piedra de Godella y la de la derecha de Bateig. Se distingue cmo a lo largo del

tiempo esta muestra siempre registra una mayor temperatura, por lo que podemos corroborar

que cuando la muestra tiene mayor densidad tambin registra una mayor temperatura.

3.4. Deterioro por prdida de densidad

In situ

En la Figura 14 podemos ver una zona del zcalo de piedra de Godella. Todos los sillares

son del mismo tipo de piedra, situados en la misma orientacin (Oeste), pero en la parte

izquierda de las imgenes se ha producido alveolizacin. Adems, las condiciones de

temperatura y humedad son las mismas al tomar las imgenes termogrficas en el mismo

momento.

Las imgenes termogrficas indican cmo la zona deteriorada ve reducida su temperatura

hasta en un 15 %, ya que la zona izquierda tiene una temperatura media de T1 = 4,1 C y la de la

derecha T2 = 4,8 C (Tabla 1).

En laboratorio

Si humedecemos las muestras y dejamos que se evaporen, mientras que registramos su

peso obtenemos que la muestra degradada tiene una menor temperatura. Incluso, recin

humedecidas ya observamos que la muestra degradada muestra una menor temperatura (Figura

15 y Tabla 1). La muestra 22 no se ha humedecido, mientras que las muestras 23 y 24 s lo han

hecho.

4. DISCUSIN

La termografa infrarroja pasiva, que tiene en cuenta la energa del sol para calentar/enfriar

los cerramientos de forma cclica nos aporta una gran informacin sobre los materiales de

construccin y su estado de conservacin.

En primer lugar, el ascenso de agua por capilaridad a travs de los muros es en general un

proceso largo en el tiempo y que tiende a estabilizarse segn las condiciones de evaporacin

ambientales y las propiedades de difusin a travs del material, aspectos que hemos corroborado

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

14

en el laboratorio. En el caso estudiado, la altura terica de equilibrio tiene un valor medio de

0,7 m (Tabla 1). Esta altura que alcanza el frente hmedo se diferencia en la imagen

termogrfica, incluso mostrando la posicin que alcanza en cada momento (Figura 8).

En el laboratorio se ha comprobado el efecto refrigerante de la evaporacin y su relacin

con la temperatura del material, llegando a la conclusin de que al inicio del proceso se reduce

notablemente la temperatura debido a que el cambio de fase lquida a gaseosa pierde

temperatura y conforme transcurre el tiempo y el material pierde humedad tiende a igualar su

temperatura con la ambiental.

El ascenso de agua por capilaridad est relacionado con la precipitacin de sales. En los

casos en que lleguen hasta el exterior (eflorescencias) o justo antes (escamas), se registran con

diferente temperatura debido a que no poseen la misma densidad del material que compone el

cerramiento (Tabla 1). La termografa infrarroja tambin se ha mostrado til en el diagnstico

de escamas o desconchados (Figura 10). El deterioro producido en forma de lajas paralelas a la

superficie aunque se separen ligeramente del resto del material, muestra una reduccin de

temperatura significativa.

Para identificar dos materiales, como pueden ser dos tipos de piedra, las condiciones

ambientales deben de ser las mismas (igual temperatura y humedad relativa), ya sea sobre el

edificio de estudio o en laboratorio (Figuras 11 y 12), obteniendo que los materiales con mayor

densidad aparente y con menos porosidad reflejan una mayor temperatura (Tabla 1).

Si analizamos un mismo material, adems de mantener constantes las condiciones de

contorno, hemos de considerar que la densidad real es la misma, pero no as la densidad

aparente, ntimamente relacionada con la porosidad. En este caso, la termografa muestra con

menor temperatura aquellas reas del material con menor densidad aparente, y por tanto, con

mayor porosidad (Figura 14). En laboratorio tambin se provoc el deterioro artificial de una

muestra con cido clorhdrico y se comprob que, efectivamente, la muestra con menor

densidad aparente registraba una menor temperatura.

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

15

Cuanto mayor sea el nmero de ensayos de laboratorio que realicemos, ms datos

conoceremos. Sin embargo, los ensayos destructivos no siempre son adecuados porque

degradan el estado de los materiales y en algunos casos la integridad del edificio.

Por un lado, podemos conocer la respuesta trmica de los materiales y su patologa con

ayuda de la tecnologa termogrfica, y por otro lado, los resultados de los ensayos.

Relacionando la informacin obtenida por estas dos vas, llegamos a un mejor diagnstico de

los materiales, llegando a observar las etapas previas al deterioro y, de esta manera, anticiparnos

e iniciar la intervencin ms adecuada en cada caso.

5. CONCLUSIONES

Antes de intervenir en un edificio, restaurando o rehabilitndolo, es necesario estudiar su

historia, los documentos originales y, sobre todo, analizar el estado en que se encuentran los

materiales de construccin. En este artculo relacionamos las propiedades ms importantes del

estado de deterioro de materiales ptreos con imgenes infrarrojas.

Lesiones tan importantes en los edificios histricos como la formacin de sales,

eflorescencias, escamas, desconchados, as como los procesos de alveolizacin y arenizacin

requieren un estudio y anlisis el cul debe iniciarse con el diagnstico y reconocimiento del

edificio.

La tcnica de la termografa puede ayudarnos a detectar estas lesiones creando una medida

sostenible que sustituye el uso de mtodos destructivos.

Una gran parte de las lesiones producidas en los materiales de construccin se deben al

efecto del agua de lluvia. Podemos observar el efecto refrigerante cuando el agua se evapora de

la superficie de la fachada, identificando el perfil de humedad que ha ascendido por capilaridad,

as como a qu altura se encuentra en cada momento.

El ascenso de agua del subsuelo por capilaridad genera un perfil en los muros que se puede

identificar en las imgenes termogrficas, contrastando los resultados con los ensayos de

laboratorio y los resultados tericos (Tabla 1).

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

16

Las sales solubles, al precipitar en la superficie aumentan localmente la densidad del

paramento y se aprecian contrastadas en la cmara termogrfica.

La piedra de Godella tiene una mayor porosidad que la de Ribarroja segn los anlisis

realizados. La densidad aparente de Godella es menor que la de Ribarroja, lo que est

relacionado con su respuesta trmica y nos sirve para afirmar que cuando la densidad aparente

es mayor, tambin aumenta la temperatura registrada, caso que se ha corroborado en el

laboratorio. Podemos comparar un mismo material en diferentes zonas, pero con las mismas

condiciones de contorno, relacionando as la densidad aparente de las distintas zonas con su

respuesta trmica para obtener datos de qu reas estn ms deterioradas. Aquellas zonas con

menor densidad aparente (mayor porosidad) se muestran en las imgenes termogrficas

claramente con una menor temperatura (hasta un 15%).

Esta tcnica nos permite constatar aquellas zonas en las que estn a punto de desprenderse

lajas o partes de roca se aprecian fcilmente en las imgenes termogrficas por diferencia de

espesor de estos trozos respecto del sillar completo.

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

17

Para el texto en espaol ir a la pgina 4

1. INTRODUCTION

Conservation measures appropriate to the building under study can only be planned and

executed following an accurate diagnosis of the deterioration including adequate and reliable

information about the materials used, as well as the factors and processes involved in the

deterioration (1). It is necessary to be very careful when examining historic buildings and the

use of non-destructive techniques such as infrared thermographic imaging facilitates the study

of materials without damaging the structure.

In the building studied, as in most historic buildings, various materials have been used. This

diversity is due to architectural considerations, constructive or artistic requirements, and

proximity to quarrying materials. The state of deterioration of a monument is characterised by

the type, intensity, and extent of the damage.

The images in this paper show the outer walls of the Seminary-School of Corpus Christi in

Valencia, Spain, comprising a stone footing course under a Valencian-style rammed earth and

brick wall some 80 cm thick.

There are several methods of using infrared technology (9), although the most common are

active thermographic imaging, which involves artificially heating the sample, and passive

thermographic imaging, where the material or the structure is heated by sunlight. When

studying large areas, such as the facades of buildings, we believe that passive thermographic

imaging is the most suitable option especially for buildings in narrow streets.

Infrared thermographic imaging was used in previous studies in relation to defects in stone

materials and images were interpreted for different points of the walls (3). Areas with thermal

discontinuities corresponded to defective points in the material, while points with similar

temperatures represent thermal inertia, or the tendency of an element to withstand temperature

changes and depending on the characteristics of the material dampness and damage (4).

Thermographic imaging has also been used to detect dampness using multi-temporal analysis

(5). Our contribution focuses on comparing laboratory and material analyses with

thermographic imaging in order to corroborate the results obtained using either technique.

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

18

In this study, we used a FLIR B335 camera that produces thermographic images at a

resolution of 320 x 240 pixels, with a temperature range of -20 to +120 C and an accuracy of

less than 50 mK NETD. The thermographic images were subsequently processed with FLIR

QuickReport software, which can vary the colour palette, temperature range, distance, as well as

calculate the maximum, minimum, and average temperatures in the study areas. The

temperature of each pixel in the image can be exported in Excel format.

2. METHODOLOGY

The procedure involves an analysis of thermographic images of a building. We compare

the results obtained from these images with laboratory tests made on the materials.

The materials analysed are traditional limestone blocks from the Valencia region, such as

stone from Godella and Ribarroja (widely used for centuries in the city of Valencia) and Bateig

Azul limestone (in use today).

Laboratory tests detail the characteristics of the material, such as density, porosity,

chemical composition, etc., and infrared imaging reveals the thermal behaviour of these

materials. The weight of the samples used in the laboratory is registered using precision scales

(0.01 g).

2.1. Infrared thermography

The ability to clearly see defects in a material depends on the difference between the

thermal characteristics of the material and the degree of homogeneity (6), while the thermal

behaviour of a material largely depend on its characteristics (thermal diffusion, porosity,

density, etc.). The emissivity value is higher than 90% for most common construction materials,

and in our case we have used a default value of 0.95 so that the results of measurements can be

considered reliable (7).

Passive thermography has been used in laboratory and in situ tests. According to Caas (8),

in the absence of heat from the sun, data obtained from thermographic imaging is very accurate

for ceramics, stone, and adobe. However, if the suns rays shine on a facade then the thermal

response of the material is altered. The thermal images shown in this study were taken before

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

19

dawn, when the material was at its coolest, and this enables us to make fewer errors when

comparing data and images.

The temperature difference between materials is largely due to density and specific heat,

and in particular, thermal inertia. Stone has considerable capacity to store energy and takes

longer to heat or cool than materials such as brick.

We linked the thermal images with some of the properties of stone, and examined those

properties that are linked to the deteriorating state of the building as they involve water

circulation mechanisms in porous media.

Building materials are porous and can deteriorate through moisture penetration, compound

dissolution, salt migration and crystallisation, or volumetric changes such as swelling, cracking,

and flaking (2).

2.2. Test description

Rising dampu

The walls of the building sit on humid ground. Dampness rises through the walls due to

capillary action, while drying occurs on the walls due to surface evaporation. There is normally

an equilibrium between the two phenomena that generates a wet front or tide mark of capillary

action.

The drying process can be divided into two stages: the first corresponds to evaporation

from the surface and depends on capillary action and the nature of the solution and is a linear

function in time (13). The second stage has a much slower rate of evaporation and corresponds

to the water vapour diffusion through the porous medium towards the surface (14, 15).

The formula for capillary action is (16):

H = 2 ! ! ! cos " / (r ! # ! g) [1]

Where, !: surface tension, ": contact angle, r: capillary radius, #: liquid density, g: gravity.

The equilibrium formula (17) between capillary action and evaporation is:

h = S (b / (2 ! e ! "

w

)

1/2

[2]

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

20

Where, h: capillary equilibrium height; S: absorption capacity; b: wall thickness; e:

evaporation rate per unit of humid surface area; "

w

: water content in the humid region (volume

of water for unit volume of material).

To apply Equation [2] we use the following data (17): the absorption capacity S of the

limestone is in the range (0.5-1.5) mm/min

1/2

so we chose as an average value 1.0 mm/min

1/2

.

The fraction of volume of porosity f is generally and approximately 0.25, and in the knowledge

that "

w

= 0.85f, we assume "

w

= 0.2. We assume the wall to be 800 mm thick. For the

evaporation rate, we assume the value of e = 0.004 mm/min (a rate four times greater than the

average annual potential evaporation in the UK). We ignore the action of gravity. In this way,

we obtain an equilibrium height of h = 0.71 m. This theoretical measure provides a reference

with respect to the actual level reached at any time, as the balance varies depending on weather

conditions.

The surrounding stone footing has a height between 0.5 and 1.5 m, and there are areas

where the rising damp wet front reaches the rammed earth wall (Figure 1).

Tests in the laboratory were based on UNE-EN 1925:1999: Test methods for natural stone

determination of coefficient of water absorption by capillary action which specifies a method

for determining the coefficient of water absorption by capillary action of natural stone. In

accordance with this norm, the results (see the graph in Figure 2) show the mass absorbed in

grams divided by the area of the submerged base of the test area in m

2

, based on the square root

of the time in seconds. The graph shows two straight lines that indicate the value of C

1

on the

slope of the first stage,

where C

1

= (m

i

m

d

) / A ! et

i

[3]

With m

i

: mass for moment i (g); m

d

: dry mass (g); A: area of the submerged base (m

2

); t

i

:

duration of a moment (s).

Salt crystallisation

Efflorescence is the crystallisation of salts on the surface of the material. A hard black scab

or crust may be produced that contains various carbonaceous products of pollution (including

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

21

soot and dust). Scaling, scabbing, or flaking produces laminas a few millimetres thick and

parallel to the surface (21).

This is caused by salt crystals, such as potassium or sodium sulfates, commonly found in

wall materials, and occurs above all in the summer. Efflorescent salt marks indicate points of

evaporation on the surface of porous materials, or with the same frequency, just below the

surface and within the pores.

Identification of the characteristics of different materials

In the laboratory, we compared two limestone samples of differing densities. One sample

was from the Godella stone quarry (D

a

= 2.55 g/cm

3

) and the other sample was from the Bateig

quarry (D

a

= 2.21 g/cm

3

). The test consisted of maintaining the samples for 72 hours at 70 5

C, as in other procedures for natural stone, and recording with a thermographic camera the heat

loss over time (in seconds). The room temperature was 24.3 C and relative humidity was

50.3%.

Deterioration caused by loss of density

Density expresses the relationship between the amount of material and volume. The greater

the density, the greater the conductivity exponentially (11). The apparent density is a magnitude

applied to porous materials, which typically contain air gaps, so that the total density is less than

the density would be if the material were compacted.

Deterioration caused by loss of density in the material has been previously studied for other

materials such as wood (12).

In the laboratory, we forced the deterioration of the material by adding hydrochloric acid

(25% HCl) as described by D'Orazio (23). Acid partially dissolves the limestone, and leaves

insoluble residues. In this way, we decreased the apparent density of the sample.

3. RESULTS

Table 1 summarizes the results of the tests performed, both in situ and in laboratory and in

some cases, theoretical.

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

22

3.1. Capillarity

In situ

Once a structure is damp, the factors on which drying depend are: temperature, relative

humidity, microenvironment, porosity, mechanical behaviour of the material, and duration of

the humid/drying cycle (24).

Figure 3 clearly shows how the curve generated by rising damp capillary action of

groundwater is reflected in the infrared image.

In laboratory

The results of capillary water absorption test with quarry samples demonstrate that

capillary action in this material is slow.

Recent experiments have shown that higher moisture content means higher material

temperatures when compared with dryer parts or materials (2). The cooling effect from

evaporation is evident as the temperature is lower than the surrounding temperature.

Additionally, the properties of the material significantly influence the rate of evaporation and,

therefore, the speed at which a material yields moisture into the atmosphere.

In laboratory tests performed following the work of Gaius (22) it can be seen that

evaporation begins once a material is dampened, and the surface temperature clearly falls. As

the material loses moisture, the surface temperature and the surrounding air temperature begin

to equalise.

In the laboratory, we conducted an experiment that consisted of observing and recording

the evolution over time of the drying process of the samples (Figure 4). Figure 5 shows the

thermographic images for three stages of the evaporation process. Of the six samples, the first

two (left) correspond to curve (a); the centre two to curve (b); and the last two (right) to curve

(c). In this greyscale image, black indicates lower temperatures (up to 18.7 C), and white

indicates higher temperatures (room temperature is 24.3 C). It can be seen how the two

samples on the right remain at room temperature and humidity (and are consequently difficult to

see). As the experiment advances, the other four samples lose moisture and so their

temperatures approach room temperature. Figure 6 (left) shows the moisture content as a

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

23

percentage of the dry weight of the six samples, and illustrates how weight loss evolves over

time. The graph shows three curves, each curve representing the average of two samples with

differing levels of moisture and it can be seen how these samples tend to equilibrate with the

moisture level in the atmosphere. Curve (a) refers to two samples that were immersed in water

for 72 hours, long enough to absorb more water than the other samples; samples (b) were only

immersed for 5 minutes; the (c) samples were references for room temperature (24.3 C) and

humidity (52.9%). The results are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 6 (right) also shows the change in the temperature of the samples. The curve (a)

samples are wetter, take longer to evaporate the absorbed water, and therefore maintain a low

temperature for longer. Curve (b) samples are drier, evaporate more easily, and the temperature

begins to rise more quickly. Curve (c) samples maintain initial moisture and temperature at

constant levels.

3.2. Salt crystallisation

Theoretical

A distinct type of deterioration due to the crystallisation of salts in the material (20) (Figure

7) is produced in function of the speed of evaporation (V

1

), and speed of water migration

towards the surface (V

2

).

The consequences of the accumulation of salt can block pores and capillaries through

which water evaporates, pushing the wet front or tide mark upwards and so increasing moisture

levels (18), reducing the capillary absorption coefficient (19). Moreover, the constant

dissolution and recrystallisation of salts, as caused by changes in humidity and temperature, can

damage a building material. Sodium sulphates from groundwater can be particularly destructive

to buildings and monuments (25).

In situ

The wall in Figure 8 clearly shows rising damp on a facade that faces north and so never

receives direct sunlight. Depending on the speed of evaporation (V

1

), efflorescence may appear.

A thermographic image shows a set of colours that represents the temperature for each point. In

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

24

this figure, a temperature graph for the material is superimposed on an axis so that we can

quantify temperature variations.

The facade in Figure 9 faces south and receives sunlight, therefore the speed of evaporation

(V

1

) is greater than in the previous case and the pathology generated is scaling as shown in the

figure.

The Ribarroja stone positioned at the doorway of the Seminary-School of Corpus Christi is

suffering degradation in parallel lines that is generating a series of flakes at the surface. Not all

the flakes are visible to the naked eye, but they are easily detected with thermal imaging (Figure

10). The flaking suffered by the stone involves the separation of one or more layers (altered or

not) of uniform thickness (several millimetres). These flakes run parallel to each other and the

structural line or a fault line in the stone (10). The flakes are thin and cool rapidly.

Figure 10b shows the pathology in detail. Flakes are forming and coming loose. Where the

flakes have not become detached we can see the surface of the stone, and where no flakes

remain we can see the inside of the stone blocks.

3.3. Identification of the characteristics of different materials

In situ

Figure 11 illustrates two types of stone, the footing being made of stone from Godella (left) and

stone from Ribarroja (right). The thermographic image was taken at 7:12 am, after about 12

hours without sunlight, and the air temperature was 7.3 C. The analytical data is given in Table

2. Bearing in mind that Ribarroja stone is less porous and denser (mean values), the

thermographic image shows a thermal response 20% higher than that of Godella stone (Table

1). Denser and more compact stone has greater thermal inertia and better maintains a

temperature.

In laboratory

Figures 12 and 13 show the loss of temperature (the Godella sample is on the left and the

Bateig sample is on the right). It can be seen how over time this sample always registers a

higher temperature, and so we can confirm that when a sample has a higher density it also

maintains higher temperatures.

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

25

3.4. Deterioration caused by loss of density

In situ

In Figure 14 we can see an area of the stone footing made from Godella stone. All the

blocks are of the same type of stone and positioned facing west, but in the left part of the images

it can be seen that alveolisation has occurred. Temperature and humidity conditions were

identical as the thermographic images were taken at the same time. The thermographic images

show how the temperature in the damaged area is reduced by 15%, since the left area has an

average temperature of 4.1 C and the right area a temperature of 4.8 C (Table 1).

In laboratory

We moistened the samples and then left them to evaporate. We found that the degraded

sample had a lower temperature. Even newly moistened degraded samples showed lower

temperatures (Figure 15 and Table 1). Sample 22 was not moistened, unlike samples 23 and 24.

4. DISCUSSION

Passive infrared imaging, which takes into account the cyclical heating affect of the sun,

can provide considerable information on building materials and their conservation status.

We have confirmed in the laboratory that rising damp, or capillary water action through

walls, is generally a long process and tends to stabilise according to the environmental

conditions for evaporation and the diffusion properties of the material. In the studied case, the

average theoretical equilibrium height is 0.7 m (Table 1). The height reached by the wet front

can be seen in the thermographic image as well as the position reached in each moment

(Figure 8).

In the laboratory, the cooling effect of evaporation and its relation with the temperature of

the material was confirmed. It was shown that at the beginning of the process the temperature

falls significantly because of the transformation from liquid to gas. Over time, the material loses

humidity and its temperature tends to equalise with the air temperature.

The capillary action of rising damp is linked to salt precipitation. In cases where salts reach

the surface (efflorescence) or just below the surface (scaling) differences in temperature are

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

26

recorded because the stone no longer has same density as the rest of the stone in the wall (Table

1). Infrared thermographic imaging has also been useful in the diagnosis of scaling and flaking

(Figure 10). Deterioration in the form of flakes that are parallel to the surface but slightly

separated from the rest of the stone shows a significant temperature reduction.

To identify two materials, such as two types of stone, environmental conditions must be the

same (temperature and relative humidity), either at the building or in a laboratory (Figures 11

and 12), obtaining that materials with higher density and with less porosity reflect a higher

temperature (Table 1).

Constant conditions must be maintained when analysing the same material, and we must

consider that while the actual density is the same, apparent density differs and is closely related

to porosity. In this case, thermographic images show lower temperatures for areas with lower

apparent density, and therefore higher porosity (Figure 14). In the laboratory, artificial

deterioration was caused by adding hydrochloric acid to a sample and it was found that the

sample with the lowest density recorded the lowest temperature.

The more tests we perform, the more details we generally learn. However, destructive tests

are not always appropriate because they degrade materials, and in some cases, may degrade the

integrity of the building.

We can discover the thermal response of materials and their pathology using thermographic

imaging technology or laboratory testing. By comparing the information obtained by both

methods, we can produce a better diagnosis and observe the stages prior to deterioration and

thus anticipate and initiate appropriate intervention.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Before restoring or rehabilitating a building it is necessary to study its history, the original

documentation, and analyse the condition of the construction materials. In this article, we

illustrate with infrared images the most important properties of deteriorated stone materials.

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

27

Deterioration in important historical buildings (such as the formation of efflorescence,

flaking, powdering, and alveolarisation) requires an analysis that should begin with a diagnosis

and survey of the building.

Thermographic imaging can help detect these deteriorations and create a sustainable

approach that avoids the use of destructive methods.

A large part of the damage caused to building materials is due to the effect of rainwater.

We can observe the cooling effect when water evaporates from the surface of a facade, as well

as identify the wet front caused by rising damp, and the height reached by dampness at any

given moment.

The rise of groundwater by capillary action (rising damp) generates a wet front within the

walls that can be identified by thermographic images, and the results can be compared with

laboratory or theoretical results (Table 1).

When soluble salts precipitate on the surface, the local density increases and this effect can

be seen in thermographic images.

The analysis shows that stone from Godella is more porous than stone from Ribarroja. The

apparent density of Godella stone is less than Ribarroja stone, and this is confirmed by the

thermal response. This observation enables us to state that when the apparent density is greater,

the recorded temperature increases and this is confirmed in laboratory tests. We can test

different areas of the same material under the same conditions and compare the apparent density

of the various areas with the thermal response in order to understand which areas have suffered

the most deterioration. Areas with less apparent density (greater porosity) are shown in

thermographic images to have lower temperatures (up to 15% lower).

This technique enables us to identify areas in which flakes are about to fall loose as it is

easy to observe in thermographic images the effects of the reduced thickness of the flakes when

compared to undamaged rock.

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

28

REFERENCIAS/REFERENCES

(1) Fitzner, B. en VV.AA. Tcnicas de diagnstico aplicadas a la conservacin de los

materiales de construccin en los edificios histricos. Sevilla: Junta de Andaluca, 1996.

(2) Vlek, J., Kruschwitz, S., Wostmann, J., Kind, T., Valach, J. Kopp, C., Lesk, J.

Nondestructive investigation of wet building material: multimethodical approach.

Journal of performance of constructed facilities, sep-oct 2010, 462-472. DOI:

10.1061/(ASCE)CF.1943-5509.0000056.

(3) Danese, M., Demsar, U., Masini, N., Charlton, M. Investigating material decay of

historic buildings using visual analytics with multi-temporal infrared thermographic

data. Archaeometry 52, 3 (2010) 482-501. DOI: 10.1111/j.1475-4754.2009.00485.x.

(4) Campbell, J.B. Introduction to remote sensing, 2 ed., Taylor & Francis, London, 1996.

(5) Lerma, JL., Cabrelles, M., Portals, C. Multitemporal thermal analysis to detect moisture

on a building faade. Construction & Building Materials 25 (2011) 2190-2197. DOI:

10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2010.10.007.

(6) Meola, C.; Carlomagno, G. M.; Giorleo, L. The use of infrared thermography for

materials characterization. Jorunal of Materials Processing Technology 155-156, pp.

1132-1137. DOI: 10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2004.04.268.

(7) Rodrguez Lin, C. Inspeccin mediante tcnicas no destructivas de un edificio

histrico: oratorio San Felipe Neri (Cdiz). Informes de la Construccin 63, 2011, pp.

13-22. DOI: 10.3989/ic.10.032.

(8) Caas I. Thermal-physical aspects of materials used for the construction or rural

buildings in Soria (Spain). Construction & Building Materials 19 (2005), pp. 197-211.

DOI: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2004.05.016.

(9) Mercuri F, Zammit U, Orazi N, Paoloni S, Marinelli M, Scudieri F. Active infrared

thermography applied to the investigation of art and historic artefacts. J Therm Anal

Calorim (2011) 104:475485. DOI 10.1007/s10973-011-1450-8.

(10) Ordaz, J.; Esbert, R.M. Glosario de trminos relacionados con el deterioro de las piedras

de construccin. Materiales de Construccin, vol. 38, n 209, ene-feb-mar, 1988.

(11) Gozlez Cruz, E.M. Seleccin de materiales en la concepcin arquitectnica

bioclimtica. Instituto de investigaciones de la Facultad de Arquitectura y Diseo,

Universidad de Zulia. Venezuela, 2003.

(12) Rodrguez-Lin, C.; Morales-Conde, M.J.; Rubio-de Hita, P.; Prez-Galve, F. Anlisis

sobre la influencia de la densidad en la termografa de infrarrojos y el alcance de esta

tcnica en la deteccin de defectos internos en la madera. Materiales de Construccin,

vol. 62, n 305, pp. 99-113, 2012. DOI: 10.3989/mc.2012.62410.

(13) Hammecker, C. The importance of the petrophysical properties and external factors in

stone decay on monuments. Pageoph 1995; 145:337-61.

(14) Scherer, G.W. The theory of drying. J Am Ceram Soc 1990; 73:3-14.

(15) Freitas, D.S. Pore network simulation of evaporation of a binary liquid from a capillary

porous mdium. Transp. Porous Media 2000; 40:1-25. DOI:

10.1023/A:1006651524722.

(16) Rirsch, E., Zhang, Z. Rising damp in masonry walls and the importance of mortar

properties. Construction and Buildings Materials, 24 (2010), 1815-1820. DOI:

10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2010.04.024.

(17) Hall, C., Hoff, W.D. Water transport in brick, stone and concrete. London: Spon Press,

2002.

(18) Oliver, A. Dampness in buildings. Oxford: BSP Professional Books; 1988.

(19) Buj, O.; Lpez, P.L.; Gisbert, J. Caracterizacin del sistema poroso y de su influencia en

el deterioro por cristalizacin de sales en calizas y dolomas explotadas en Abanto

(Zaragoza, Espaa). Materiales de Construccin, vol. 60, n 299, pp. 99-114, 2010.

DOI: 10.3989/mc.2010.50108

(20) Rossi-Manaresi, R. Degradacin del Patrimonio. Conferencia celebrada en la Facultad de

Geografa e Historia. Valencia, 1988.

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

29

(21) Ordaz, J., Esbert, RM. Glosario de trminos relacionados con el deterioro de las piedras

de construccin. Materiales de Construccin, vol. 38, n 209, 1988.

(22) Gayo, E.; De Frutos, J.; Palomo, A.; Massa, S. A Mathematical Model Simulating the

Evaporation Processes in Building Materials: Experimental Checking through Infrared

Thermography. Building and Environment, vol. 31, n 5, pp. 469-475, 1996. DOI:

10.1016/0360-1323(96)00007-8.

(23) DOracio, M.; Munaf, P. A methodology for the evaluation of the hygrometric and

mechanical properties of consolidated stones. International Journal of Architectural

Heritage. 2013. In press.

(24) Binda, L.; Gardani, G.; Zanzi, L. Nondestructive testing evaluation of drying process in

flooded full-scale masonry walls. Journal of performance of constructed facilities, sep-

oct 2010, pp. 473-483. DOI: 10.1061/(ASCE)CF.1943-5509.0000097.

(25) De Clercq, H. Proceedings from the conference on salt weathering on buildings and stone

sculptures. Copenhagen: Tech University of Denmark; 2008.

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

30

TABLAS/TABLES

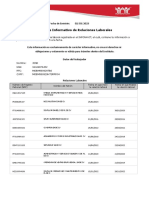

Tabla 1/Table 1

Resultados de los ensayos realizados / Results of tests

ENSAYO / TEST TIPO/TYPE MATERIAL RESULTADO/RESULT

Capilaridad /

Capillarity

Terico /

Theoretical

Caliza / Limestone Altura / Height 0.71 m.

Laboratorio /

Laboratory

Bateig

Ta = 83% Evaporacin / Evaporation

Tb = 88%

Tc = 100%

In situ / On

site

Godella

Variable segn condiciones climticas (T y

HR). Altura medida con la cmara trmica /

Variable depending on weather conditions (T

and RH). Height measured with thermal camera

1.30 m.

Cristalizacin de sale /

Crystallization of salts

Terico /

Theoretical

Bateig

Evaporacin en regiones ms fras, zonas de

concentracin de sales. / Evaporation in colder

regions, areas of salts concentration.

In situ / On

site

Arenisca / Sandstone

Eflorescencias / Efflorescence

T1 = 100% T2 = 94%

Ribarroja

Escamas / Flakes

T1 = 100% T2 = 56%

Identificacin de

materiales / Material

identification

Laboratorio /

Laboratory

Godella D1 = 2,55

t0 t1 t2 t3

100% 64% 57% 34%

Bateig D2 = 2,21 86% 50% 43% 34%

In situ / On

site

Godella D1 = 2,60 P: 15% T1 = 80%

Ribarroja D2 = 2,64 P: 5% T2 = 100%

Deterioro por densidad

/ Density deterioration

Laboratorio /

Laboratory

Bateig D1 = 2,21

D2 = 1,91

T1 = 100%

T2 = 81%

In situ / On

site

Godella D1 = 2,60

D2 = 2,12

T1 = 100%

T2 = 85%

D: densidad aparente / bulk density. P: porosidad / porosity. t: tiempo / time. T: temperatura / temperatura

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

31

Tabla 2/Table 2

Identificacin de distintos materiales por sus caractersticas / Identification of different materials

for their characteristics

MUESTRA / SAMPLE GODELLA (IZQ) / (LEFT)

RIBARROJA (DCHA) /

(RIGHT)

Densidad relativa media /

Average relative density

2.60 (g/cm

3

) 2.64 (g/cm

3

)

Porosidad media / Average

porosity

15% 5%

Temperatura / Temperature 80% (3.27 C) 100% (4.07 C)

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

32

PIES DE LAS FIGURAS/ FIGURE CAPTIONS

Figura 1/Figure 1. Ascensin capilar en un muro de piedra y tapial. / Capillary rise in a stone

and rammed earth wall.

Figura 2/Figure 2. Absorcin de agua por capilaridad en funcin de la raz cuadrada del tiempo

(segundos). / Absorption of water by capillary action plotted against the square root of time

(seconds).

Figura 3/Figure 3. Ascensin del agua por capilaridad vista (a) con la cmara termogrfica, (b)

fotografa y (c) superposicin de (a) y (b). / Capillary rise of the water viewed in (a) with a

thermographic camera, (b) a photograph and (c) the superimposition of (a) over (b).

Figura 4/Figure 4. Equipo necesario para la toma de imgenes termogrficas y registro del

peso de las muestras. / Equipment required for thermographic imaging and sample weight.

Figura 5/Figure 5. Termografas del proceso de evaporacin. / Evaporation process of

thermography.

Figura 6/Figure 6. Prdida de peso y temperatura al evaporarse el agua de las muestras. /

Weight loss and temperature while evaporating the water from the samples.

Figura 7/Figure 7. Morfologa del deterioro en el material producida por la cristalizacin de

sales. / Material deterioration morphology cause by salt crystallization.

Figura 8/Figure 8. Zcalo con eflorescencias, (a) foto, (b) termografa y (c) detalle de

eflorescencias. / Ashlar with efflorescence, (a) thermographic image, (b) photograph and (c)

superimposition of (a) over (b).

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

33

Figura 9/Figure 9. Zcalo con escamas, (a) foto, (b) termografa y (c) detalle de las escamas. /

Ashlar with flakes, (a) thermographic image, (b) photograph and (c) superimposition of (a) over

(b).

Figura 10/Figure 10. Vista general (a) y detalle (b) de un desconchado. Termografas (arriba),

fotografas (abajo). / General view (a) and detail (b) of an instance of spalling. Thermographic

images (top) and photographs (bottom).

Figura 11/Figure 11. Comparativa entre la piedra de Godella y la de Ribarroja. Fotografa (a) y

termografa (b). / Comparison between Godella and Ribarroja stone. Photograph (a) and

thermographic image (b).

Figura 12/Figure 12. Termografa de la prdida de temperatura de dos muestras con diferente

densidad. / Thermography of temperature loss of two samples with different density.

Figura 13/Figure 13. Prdida de temperatura de dos muestras con diferente densidad. /

Temperature loss of two samples with different density.

Figura 14/Figure 14. Vista general (a) y detalle (b) del zcalo con distinta erosin superficial.

Fotografas (arriba) y termografas (abajo). / General view (a) and detail (b) of the socle with

clear superficial erosion. Photographs (top) and thermographic images (bottom).

Figura 15/Figure 15. Fotografa y termografa de 3 muestras, 23 y 24 recin humedecidas. /

Photography and thermography of 3 samples, 23 and 24 just moistened.

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

34

Figura 1/Figure 1

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

35

Figura 2/Figure 2

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

36

Figura 3/Figure 3

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

37

Figura 4/Figure 4

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

38

Figura 5/Figure 5

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

39

Figura 6/Figure 6

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

40

Figura 7/Figure 7

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

41

Figura 8/Figure 8

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

42

Figura 9/Figure 9

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

43

Figura 10/Figure 10

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

44

Figura 11/Figure 11

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

45

Figura 12/Figure 12

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

46

Figura 13/Figure 13

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

47

Figura 14/Figure 14

C. Lerma, . Mas, E. Gil, J. Verchera, M. J. Pealvera

Mater. Construcc., 2013. eISSN: 1988-3226. Accepted manuscript. doi: 10.3989/mc.2013.06612

48

Figura 15/Figure 15

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Manual-3d-Studio-Max-Avanzado ESPAÑOL PDFDokument45 SeitenManual-3d-Studio-Max-Avanzado ESPAÑOL PDFlulu2489b100% (4)

- Manual Técnico de ConstrucciónDokument264 SeitenManual Técnico de ConstrucciónEstíbaliz Martín del Estal100% (2)

- Cama Profunda Como Sistema Alternativo en Produccion PorcinaDokument8 SeitenCama Profunda Como Sistema Alternativo en Produccion PorcinaVictor AbreuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Patologias - Causas y Soluciones PDFDokument120 SeitenPatologias - Causas y Soluciones PDFjezzmi90% (10)

- Nutrientes Especificos2013Dokument266 SeitenNutrientes Especificos2013Francisco Xavier Gonzalez PeñaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Patologia de La MaderaDokument18 SeitenPatologia de La MaderaGerthy BaumannNoch keine Bewertungen

- Desconsuelo Al Amanecer - Alejandra AndradeDokument374 SeitenDesconsuelo Al Amanecer - Alejandra AndradeLaura GutièrrezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lagos Linda U5T2Guia ContableDokument15 SeitenLagos Linda U5T2Guia ContableLinda Lagos100% (1)

- ¿Qué Es Ganoderma?Dokument22 Seiten¿Qué Es Ganoderma?EdgarBusiness100% (1)

- TEO1 ProgramDokument1 SeiteTEO1 ProgramEdwien FtsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Indice Analisis ArquitectonicoDokument1 SeiteIndice Analisis ArquitectonicoJaime Jesús Segura GranadosNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1585 ArpheDokument294 Seiten1585 Arphepfunes100% (2)

- Portada ConocimeintoDokument2 SeitenPortada ConocimeintoJaime Jesús Segura GranadosNoch keine Bewertungen

- IntroducciónDokument16 SeitenIntroducciónJaime Jesús Segura GranadosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manual 2 CalorDokument244 SeitenManual 2 CalorJaime Jesús Segura GranadosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Agricola Jiquilpan 2009-2010Dokument14 SeitenAgricola Jiquilpan 2009-2010Jaime Jesús Segura GranadosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dispositivos de Seguridad ResumenDokument17 SeitenDispositivos de Seguridad ResumennathaliaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Proceso Productivo Del AlcoholDokument2 SeitenProceso Productivo Del AlcoholDIANA DELACRUZZNoch keine Bewertungen

- Derivada direccional y vector gradienteDokument14 SeitenDerivada direccional y vector gradienteDiana Carolian CuyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reseña CRITICADokument7 SeitenReseña CRITICAYissett De La HozNoch keine Bewertungen

- Informe de Practicas Pre ProfesionalesDokument24 SeitenInforme de Practicas Pre ProfesionalesSusan ArmasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Volcanes del Perú: Guía de los principalesDokument8 SeitenVolcanes del Perú: Guía de los principalesCristhian Andres Damian CoveñasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Taller de Seguimiento RevisoriaDokument9 SeitenTaller de Seguimiento RevisoriaErika SanchezNoch keine Bewertungen