Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Ap Lit Review Session

Hochgeladen von

api-279233311Originalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Ap Lit Review Session

Hochgeladen von

api-279233311Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Castillo Munoz 3

First Step to Primate Equality: Understanding They Are Conscious

Philosophy professor from the University of New York (Toronto), Kristin Andrews, focuses

her research on the nature of social cognition and examines human social relations and the

relationships among, and between, animals of different species. In her essay The First Step

in the Case for Great Ape Equality: The Argument for Other Minds, Andrews states that

before nonhuman primates can be considered equal, the idea that they (and other animals) are

not conscious must be demolished (131). Andrews argument is partially based on the fact

that apes can also rationally think and also possess problem-solving skills. In her own words

she states that one who accepts the existence of humans minds is then rationally compelled

to accept the existence of great ape minds in general (132). This section outlines

noninvasive experiments that prove NHPs are rational and self-conscious living creatures.

Since the beginning of the 20 century, primatologists have focused on determining

th

whether communication among NHPs is intentional or not; Professor Scott-Phillips from

Durham Universitys anthropology department, however, has focused his research on the

structure of nonhuman primate communication while also tying his results to the origins of

language. In other words, Scott-Phillips article, Nonhuman Primate Communication,

Pragmatics, and the Origins of Language, traces the origins of human language to NHP

communication by telling us that ape communication involves the use of metacognitive

abilities that ... were exapted for use in what is an evolutionarily novel form of

communication: human ostensive communication (56). Scott-Phillips makes reference to

the first experiments that focused on comparing human to ape communication. As a early as

1920, playback experiments in which animal vocalization were recorded and then played to a

different group of animals, but of the same species. Their reactions were then observed and

compared to words in human language (Seyfarth, Cheney, Marler 1980b). Nevertheless,

Castillo Munoz 4

Scott-Phillips mentions that words and monkey reactions to alarm calls identified in this

research completely rely on different cognitive mechanism and cannot be directly compared

to one another (53). This raised the question of whether apes communicate intentionally. As

well as Scott-Phillips, comparative psychologists Josep Call and Michael Tomasello, agree

that ape communication is not intentional. Nevertheless, Scott-Phillips argues that there are

other aspects of communication that are at least as important as intentionality that have

received far less attention(53). In the section Does Nonhuman Primate Communication

Use Ostension and Inference of his article, he proves that ape communication is not

ostensive by proving that ape communication uses a form of code model that allows apes to

communicate. He mentions that ape gestural communication is very sophisticated and it is

based on a process that scientist refer to as ontogenetic ritualization, in which a behavior

takes on a communicative function by virtue of its repeated use in the interactions of two (or

more) individuals (Nonhuman Primate Communication, Pragmatics, and the Origins of

Language). As a result, one can conclude that this code is simply enhanced by

metapsychological abilities that humans use to communicate, thus making it clear to see that

human language evolved from this simplistic form of ape communication.

In addition to Scott-Phillips findings, Doctor Roberta Salmi and professor Diane

Doran-Sheehy narrowed down the topic of ape communication to a specific form exhibited in

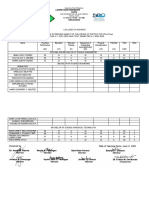

western gorillas. In the article The Function of Load Calls (Hoot Series) in Wild Western

Gorillas (Gorilla gorilla) Salmi and Doran-Sheehy established that western gorillas use loud,

long-distance calls (Hoot Series) to reunite the group in a specific place (379). To begin their

research, they first established whether hoot series were used to establish spatial proximity

among them. They outlined four criteria that needed to be met in order to exactly tell what the

function of hoot series is. First, the hoot series should vary from one individual to the other in

order to allow recipient to distinguish who was making the call and respond to the sender

Castillo Munoz 5

correspondingly. Secondly, the call

should only be emitted when the

sender and the recipient become

further apart than normal. Thirdly, the

distance between the sender and the

caller should be either stable or

increasing before the call is emitted

and should immediately decrease after

the call has been emitted. Lastly, the

call should differ from those

recipients that are in the group from those that are not (380). In order to make sure these

criteria were met, Salmi and Doran-Sheehy collected all the behavioral data and vocal

recordings over a period of fifteen months from a healthy, well-habituated group of gorillas

that lived in the Mondika Research Center located in the Republic of Congo. The conclusion

of the experiment was that between the beginning and the start of a hooting series the

distance between the sender(s) and the recipient(s) decreased significantly (See figure 1). As

a result, Salmi and Doran-Sheehy said that because inter-individual distances were

increasing prior to the calls and decreasing only after, we [Salmi and Doran-Sheehy]

conclude that hoot series function as signals for individuals to regroup (386). In addition to

ape gestural communication, Hoot series could also be considered an example of the process

Scott-Phillips referred to as ontogenetic ritualization in his article. As described above, the

repetition of the series becomes a form of communication among NHPs that although differs

from human communication, it is very similar to human communication and it is a sign of

consciousness. It is important, though, to note that there are many other aspects about

nonhuman primates, such as grief and mourning, that tell us that they are conscious.

Castillo Munoz 6

In chapter twelve of her book, How Animals Grieve, Barbara King describes

observations made by primatologists, such as Jane Goodall, as early as 1900 . King starts off

by describing two different situations, one in the wild and one in captivity, in which

chimpanzees show specific behaviors that signal ape grief. She mentions that the apes eat less

than normal, sleep less and in different places than they are used to when a companion or a

member of their group dies. King describes these behaviors as an altered routine or a

disturbed mood (129). To illustrate, King describes the death of mother chimpanzee Pansy

who lived in a Scottish safari park together with another chimpanzee mother called Blossom.

Pansy fell ill, describes King, and started having problems breathing, to the point that the

owners of the park anticipated her death. The mothers offspring, Chippy and Rosie, both

seemed to know that something was not in order and immediately started showing signs of

agitation and desperation. In Kings own words in the ten minutes before her death, they

groomed her or caressed her at what the observers judged to be a higher than usual rate

(King 130). After Pansys death different behaviors were observed: Chippy (Blossoms son)

attacked Pansys corpse by pounding her torso repeatedly times that night; Rosie (Pansys

daughter) stayed near the corpse for long periods of time; Blossom (the other mother

chimpanzee) did not sleep much and although she used to sleep on the platform on which

Pansys body lay, she did not sleep there neither did the other chimpanzees (King 131). King

expands on another example of a strange behavior in monkeys when another monkey

dies.More specifically, King discusses the action that mother chimpanzees take when their

offspring die shortly after they have been born by making reference to Peter Fashings

research which observed gelada monkey of Guassa, Ethiopia. King gives specific attention to

three cases that in which three mother gelada monkeys carry their offspring after they had

died for thirteen, sixteen, and forty-eight days. King notes that the carrying behavior does,

after all, represent a substantial energy expenditure by the mother (66). So the question

Castillo Munoz 7

remains, why do monkeys exhibit these behaviors? To the plain human eye it might seem like

the mother just does not know the baby has died, or to some it might look like another way

for NHPs to communicate a message, in this case pain and grief. Consequently, these

behaviors have over time influenced humans to start considering animals and relating with

them through stronger bonds. In order to explain these bonds, we must take into account the

ethics behind the scientific evidence that I have provided thus far. I have outlined behaviors

exhibited by nonhuman primates that leads us to think that they are rational beings with the

ability to form social relations with one another and even with humans, but in the next section

of this issue, I shall explain the ethical and scientific perspectives on the issue, accounting for

the inefficiency and immorality behind experimentation on primates.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (894)

- AP Psych All Concept MapsDokument18 SeitenAP Psych All Concept MapsNathan Hudson100% (14)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Reflection EssayDokument5 SeitenReflection Essayapi-279233311Noch keine Bewertungen

- Training Activity Matrix in Food ProcessingDokument4 SeitenTraining Activity Matrix in Food Processingian_herbasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Songs of The Gorilla Nation My Journey Through AutismDokument3 SeitenSongs of The Gorilla Nation My Journey Through Autismapi-399906068Noch keine Bewertungen

- Simran - Objectives of ResearchDokument22 SeitenSimran - Objectives of Researchsimran deo100% (1)

- Guide To IBM PowerHA SystemDokument518 SeitenGuide To IBM PowerHA SystemSarath RamineniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Expert SystemDokument72 SeitenExpert SystemMandeep RanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Psychological Testing ExplainedDokument12 SeitenPsychological Testing ExplainedUniversity of Madras International Conference100% (2)

- 7 HR Data Sets for People Analytics Under 40 CharactersDokument14 Seiten7 HR Data Sets for People Analytics Under 40 CharactersTaha Ahmed100% (1)

- Motivation LetterDokument2 SeitenMotivation Lettercho carl83% (18)

- Ap Final DraftDokument14 SeitenAp Final Draftapi-279233311Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ap Advocating Solution SectionDokument3 SeitenAp Advocating Solution Sectionapi-279233311Noch keine Bewertungen

- Reflection EssayDokument6 SeitenReflection Essayapi-279233311100% (1)

- HCP For PortfolioDokument9 SeitenHCP For Portfolioapi-279233311Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ap Defining The Problem SectionDokument3 SeitenAp Defining The Problem Sectionapi-279233311Noch keine Bewertungen

- HCPDokument9 SeitenHCPapi-279233311Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ap Introduction SectionDokument3 SeitenAp Introduction Sectionapi-279233311Noch keine Bewertungen

- Rhetorical Analysis Essay (Revised For Eportfolio)Dokument7 SeitenRhetorical Analysis Essay (Revised For Eportfolio)api-279233311Noch keine Bewertungen

- Rhetorical Analysis Essay (Highlighted For Eportfolio)Dokument7 SeitenRhetorical Analysis Essay (Highlighted For Eportfolio)api-279233311Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lit Review Essay (Revised For Eportfolio)Dokument4 SeitenLit Review Essay (Revised For Eportfolio)api-279233311Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lit Review First Draft (Highlited For Eportfolio)Dokument4 SeitenLit Review First Draft (Highlited For Eportfolio)api-279233311Noch keine Bewertungen

- Iii-Ii Final PDFDokument44 SeitenIii-Ii Final PDFChinsdazz KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Job Description: Preferably An MBA/PGDBM in HRDokument2 SeitenJob Description: Preferably An MBA/PGDBM in HRsaarika_saini1017Noch keine Bewertungen

- Advertisements and Their Impacts: A Guide to Common Writing TopicsDokument20 SeitenAdvertisements and Their Impacts: A Guide to Common Writing TopicsdumbsimpNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supply Chain Mit ZagDokument6 SeitenSupply Chain Mit Zagdavidmn19Noch keine Bewertungen

- Anaswara M G: Neelambari, Thottungal Residential Association, Westyakkara, Palakkad, Kerala, 678014Dokument3 SeitenAnaswara M G: Neelambari, Thottungal Residential Association, Westyakkara, Palakkad, Kerala, 678014AnaswaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Semisupervised Neural Networks For Efficient Hyperspectral Image ClassificationDokument12 SeitenSemisupervised Neural Networks For Efficient Hyperspectral Image ClassificationVishal PoonachaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brian Ray Rhet-Comp CVDokument8 SeitenBrian Ray Rhet-Comp CVapi-300477118Noch keine Bewertungen

- SyllabusDokument13 SeitenSyllabusKj bejidorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lullabies: Back Cover Front CoverDokument16 SeitenLullabies: Back Cover Front CovermaynarahsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tema 14Dokument6 SeitenTema 14LaiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diego Maradona BioDokument2 SeitenDiego Maradona Bioapi-254134307Noch keine Bewertungen

- Core OM - Term 1 - 2019Dokument5 SeitenCore OM - Term 1 - 2019chandel08Noch keine Bewertungen

- Undertaking Cum Indemnity BondDokument3 SeitenUndertaking Cum Indemnity BondActs N FactsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cspu 620 Fieldwork Hours Log - Summary SheetDokument2 SeitenCspu 620 Fieldwork Hours Log - Summary Sheetapi-553045669Noch keine Bewertungen

- Experiences On The Use and Misuse of The Shopee Application Towards Purchasing Behavior Among Selected Accountancy, Business and Management (ABM) Senior High School StudentsDokument7 SeitenExperiences On The Use and Misuse of The Shopee Application Towards Purchasing Behavior Among Selected Accountancy, Business and Management (ABM) Senior High School StudentsInternational Journal of Academic and Practical ResearchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civitas Academica of English Education and Stakeholders’ Un-derstanding of Vision, Missions, Goals, and Targets of English Education Department at IAIN Bukittinggi in Year 2018 by : Melyann Melani, Febria Sri Artika, Ayu NoviasariDokument7 SeitenCivitas Academica of English Education and Stakeholders’ Un-derstanding of Vision, Missions, Goals, and Targets of English Education Department at IAIN Bukittinggi in Year 2018 by : Melyann Melani, Febria Sri Artika, Ayu NoviasariAyy SykesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sains - Integrated Curriculum For Primary SchoolDokument17 SeitenSains - Integrated Curriculum For Primary SchoolSekolah Portal100% (6)

- IT1 ReportDokument1 SeiteIT1 ReportFranz Allen RanasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Faculty Screening J.ODokument2 SeitenFaculty Screening J.OIvy CalladaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CPDProgram Nurse 111919 PDFDokument982 SeitenCPDProgram Nurse 111919 PDFbrikgimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cetscale in RomaniaDokument17 SeitenCetscale in RomaniaCristina RaiciuNoch keine Bewertungen