Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Prohibiting Women From Working As Bartenders Unconstitutional - Kerala High Court

Hochgeladen von

Live LawOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Prohibiting Women From Working As Bartenders Unconstitutional - Kerala High Court

Hochgeladen von

Live LawCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

DAMA SESHADRI NAIDU, J.

-----------------------------------W.P. (C) No. 3450 of 2014 (E)

-----------------------------------Dated this the 17th day of August 2015

JUDGMENT

Introduction:

It is an issue of judicial invalidation of legislation: Rule 27A of

the Foreign Liquor Rules is impugned as being violative of Articles 14,

15 (1) & (3), 16 (1) and 19 (1) (g) of the Constitution of India.

Uncluttered by statutory references, the issue is whether a woman can

be deprived of employment solely on the ground of the alleged

disadvantage she suffers from owing to her gender. In the present

instance, women are sought to be discriminated against because of

their sex, and nothing else.

Facts in Brief:

2. The petitioners, working as waitresses/restaurant assistants

in a bar attached to a hotel in Trivandrum, faced the threat of

W.P.(C). No. 3450/2014

-2-

termination from their employment with the introduction of a new

Rule governing the Bars attached to hotels. As per the amendment of

the Foreign Liquor Rules notified as S.R.O. No. 959/2013 dated

9/12/2013, a new rule as Rule 27A is incorporated prohibiting

women from being employed in any capacity for serving liquor on

the licensed premises. In terms of the same notification, in Form FL3 under the heading Conditions, a new condition has been

incorporated as condition No. 9A which also contains the same

prohibition for engaging women in the Bars. The raison d'tre for the

introduction of Rule 27A of the Rules and the consequential

procedural measures is that the Government has received complaints

that women are being employed to serve liquor in the licensed bars.

W.P.(C). No. 3450/2014

3.

-3-

Both the petitioners, who are working as waitresses or

bartenders in an FL-3 licenced hotel, have a grievance that if the

newly incorporated rule is allowed to hold its field, the petitioners are

bound to lose their jobs and, thus, their livelihood. The petitioners do

aver that their employer has already informed them that the

management is not able to provide them any other employment in the

hotel, and that they are bound to be terminated very soon. The

petitioners Exhibit P5 representation, submitted to the respondents 1

to 3, does not seem to have evoked any response.

4. Thus, both the petitioners, being the bread-winners of their

families with children and elder members to be supported, challenge

Rule 27A of the Rules as being ultra vires of the Executive, especially

in the face of Articles 14, 15 (1) & (3), 16 (1) and 19 (1) (g) of the

Constitution of India.

Summary of Submissions:

W.P.(C). No. 3450/2014

5.

petitioners,

-4-

Mr. Thomas Abraham, the learned counsel for the

has

submitted

that

the

'conceptual

change'

of

employment has advanced the status of women in the society at

large, and any stray incidents of violence against women in their

workplace or elsewhere is not at all a valid reason for keeping them

away from any employment.

6. He further contends that no restriction can be imposed on

the basis of gender against any person working in a star hotel either

as per the norms/conditions fixed for its classification or under the

FL-3 licence or any other law in force. According to the learned

counsel, there have been no complaints whatsoever regarding any

misbehaviour by any customer towards the women employees

working in the licensed premises. When tourism is aggressively

promoted, the need for involving women in the hospitality industry

cannot be overemphasized.

W.P.(C). No. 3450/2014

7.

-5-

The Governments avowed objective in bringing about the

statutory changes in depriving the women of their employment

opportunities, according to the learned counsel, is entirely on a

misplaced assumption of its role as parens patriae. The governmental

policy, in essence, is myopic and archaic, contends the learned

counsel.

8. The learned counsel has also contended that the issue raised

in the present writ petition has been squarely covered by the decision

of the Honble Supreme Court in Anuj Garg and Others vs. Hotel

Association of India and Others1. He has also placed reliance on Githa

Hariharan v. Reserve Bank of India2, wherein the Apex Court has

adverted to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of

Discrimination against Women, 1979 (CEDAW) which was adopted in

1979 by the UN General Assembly. In the course of his submissions,

AIR 2008 SC 663

AIR 1999 SC 1149

W.P.(C). No. 3450/2014

-6-

the learned counsel has also referred to United States v. States

States v.

Virginia3, and Rajamma Vs. State of Kerala and Others4.

9. It is the specific contention of the learned counsel that by

incorporating the impugned rule by amending the Foreign Liquor

Rules,

through

S.R.O

No.

959/2013

dated

9/12/2013,

the

Government, in effect, is taking away the equality of status and

opportunity that is guaranteed to the women in the Constitution of

India. It is, according to him, a state-sponsored discrimination. The

learned counsel, sounding rhetorical, has submitted that with the

enforcement of the impugned rule, the Government has been laying

to waste welfare legislations like the Commission of Sati (Prevention)

Act, 1987, the Equal Remuneration Act, 1976, National Commission

for Women Act, 1990, the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 (28 of 1989), the

Indecent Representation of Women (Prohibition) Act, 1986, the Hindu

518 US 515 (1996)

1983 KLT 457

W.P.(C). No. 3450/2014

-7-

Succession Act, 1956, the Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961, etc.

10. The learned counsel for the petitioners has also referred to

the preamble of the

buttress

his

Universal Declaration of Human Rights to

submissions.

After

referring

to

various

other

international covenants and treaties, the learned counsel has

eventually summed up his submissions by saying that the impugned

Rule is ex facie discriminatory and ultra vires of the Government, the

Executive.

Respondents:

11.

The learned Government Pleader, in the absence of any

counter affidavit having been filed, has initially submitted that the

Government has brought about the statutory changes only with a view

to protecting the women from being exposed to dangers in

workplaces. He has further submitted that even in Bars and

restaurants women have not been prohibited from being engaged

W.P.(C). No. 3450/2014

-8-

except as bartenders. According to him, it amounts to neither

discrimination against nor deprivation of employment to women. He

has, nevertheless, submitted that in the light of the decision rendered

by the Apex Court in Anu Garg, this Court may decide the issue on

hand.

Discussion:

12. The Abkari Act is a pre-independence piece of legislation

initially enacted on 05.08.1902 by the principality of Cochin; it was,

later, made applicable to the whole of Kerala as per Act 10 of 1967,

which received the Presidential assent on 29.07.1967. It is, as the

preamble reads, a consolidating and amending act relating to the

import, export, transport, manufacture, sale and possession of

intoxicating liquor and intoxicating drugs in the State of Kerala.

Section 10 of the Act deals with the transportation of liquor or any

other intoxicating drug; section 24, with the forms and conditions of

W.P.(C). No. 3450/2014

-9-

licences, etc., whereas Section 29 delegates to the Government the

legislative power of making rules.

13. As a part of the delegated legislation, the Government of

Kerala, tracing its powers to Sections 10, 24 and 29 of the Act, has

framed the Foreign Liquor Rules with effect from 01.04.1953. The

fulcrum of the rules being Rule 13, it deals with the licences for

possession, use or sale of foreign liquor. Rule 27 of the Rules

prohibits the sale or transport of liquor by persons suffering from

leprosy or any contagious disease and the employment of such

persons in shops for the sale of liquor.

14. Through G.O. (P) No.204/2013/TD, dated 09.12.2013, the

Government of Kerala has amended the Foreign Liquor Rules by

engrafting Rule 27A, which reads as follows:

Rule 27A. No woman shall be employed in any capacity for serving

liquor in the licenced premises.

15. Further, in Form F.L.3, under the heading Conditions, after

W.P.(C). No. 3450/2014

-10-

Condition No.9, the following condition has been inserted:

9A. No woman shall be employed in any capacity for serving liquor in

the licenced premises.

16. The explanatory note appended to the Government Order,

though indicated to be not part of the notification, reads to the effect:

The Government have received various complaints that women are

being employed in licensed premises for serving liquor to their

customers. For prohibiting such practices, the Government have

decided to amend the Foreign Liquor Rules

17. In the first place, neither the principal legislation, the Abkari

Act, nor the secondary legislation, namely the Foreign Liquor Rules,

prohibits the employment of women in any liquor outlets, especially

the FL-3 licenced premisesnow, in the light of the change in the

Governmental policy, exclusively five-star hotels. In the light of this

fact, the question of the Government receiving complaints about the

hotel establishments employing women in any capacity, especially for

serving liquor, is not, by any reckoning, of much consequence. The

Government, however, presupposes that employing women to serve

W.P.(C). No. 3450/2014

-11-

liquor in the licenced premises is illegal. Since this presumed illegality

needs some statutory support, the Government has brought about

the impugned Government Order. Curious as it may sound, first, the

Government brands something illegal, without any statutory base,

though; and subsequently brings about justification by amending the

Rules. The approach of the Government is a classic case of begging

the question.

Constitutional Justification:

Justification:

18.

Raymond F. Gregory in his book Women and Workplace

Discrimination: Overcoming Barriers to Gender Equality

(2003,

Rutgers University Press) has narrated the course of discriminatory or

even anti-canon judgments rendered by the American Supreme Court

as regards the gender equality, or rather inequality, especially in

workplaces. Illinois was one of many states that barred felons and

women from becoming lawyers. In 1872, the Supreme Court in

W.P.(C). No. 3450/2014

-12-

Bradwell v. Illinois, 83 U.S. 130 (1872), affirmed Illinoiss rejection of

Myra Bradwells application for a license to practice law in the state

and took the opportunity to fix womens proper place in society:

The natural and proper timidity and delicacy which belongs to the

female sex evidently unfits it for many of the occupations of civil life.

The constitution of the family organization, which is founded in the

divine ordinance, as well as in the nature of things, indicates the

domestic sphere as that which properly belongs to the domain and

functions of womanhood. The harmony, not to say identity, of interests

and views which belong, or should belong, to the family institution is

repugnant to the idea of a woman adopting a distinct and independent

career from that of her husband.

19.

To make certain that all citizens understood womens

proper place, the Court added:

The paramount destiny and mission of woman are to fulfill the noble

and benign offices of wife and mother. This is the law of the Creator.

20. Let us move a few years ahead and see how the American

Supreme Court reacted to differential legislation vis--vis the women:

In Muller v. Oregon, 208 U.S. 412 (1908), the U.S. Supreme Court has

held that differentiated from the other sex, a woman is properly

placed in a class by herself, and legislation designed for her

W.P.(C). No. 3450/2014

-13-

protection may be sustained, even when like legislation is not

necessary for men, and could not be sustained. It is impossible to

close ones eyes to the fact that she still looks to her brother and

depends on him. This difference, according to the U.S. Supreme

Court, justifies a difference in legislation and upholds that which is

designed to compensate for some of the burdens that rest upon her.

21.

A few more years later, we may still examine the

judicial thinking in an advanced country like the USA. As recently as in

1948, the American Supreme Court persisted with its conviction that

women are dependent upon men. In Goesaert v. Cleary, 335 U.S. 464

(1948), upheld a Michigan statute that barred a woman from

employment as a bartender unless the male owner of the bar was

either her father or her husband. Ironically, the leading opinion was

rendered by none other than Mr. Justice Frankfurter. The learned

Judge has observed that Fourteenth Amendment did not tear history

W.P.(C). No. 3450/2014

-14-

up by the roots, and the regulation of the liquor traffic is one of the

oldest and most untrammeled of legislative powers.

22.

engendered

If we examine the litigation the gender issue has

across

the

Atlantic,

in

Roberts

Hopwood 5 a

metropolitan borough council had decided to pay its workers a

minimum of 4 a week, whether they were men or women and

regardless of the job they did. The House of Lords approved the

district auditor's surcharge for being overly gratuitous, given the fall

in the cost of living. Lord Atkinson said:

"[t]he council would, in my view, fail in their duty if ... [they] allowed

themselves to be guided in preference by some eccentric principles

of socialistic philanthropy, or by a feminist ambition to secure

the equality of the sexes in the matter of wages in the world of labour."

Though Lord Buckmaster, dissenting, said:

"Had they stated that they determined as a borough council to pay the

same wage for the same work without regard to the sex or condition of

the person who performed it, I should have found it difficult to say that

that was not a proper exercise of their discretion."

23. As can be seen from the ABC of Women Workers Rights

5

[1925] AC 578

W.P.(C). No. 3450/2014

-15-

and Gender Equality (Pp.8 &9, 2nd Ed. International Labour Officer,

Geneva), discrimination on the grounds of sex is a major form of

discrimination, and has been a focus of attention for the international

community since the Second World War. The protection and

promotion of women workers rights have always been integral to the

ILOs mandate. The employment of women before and after childbirth

was the subject of one of the ILOs first Conventions, dating from

1919, the very first year of the Organizations life. Convention

No.100, by guaranteeing equal pay for work of equal value, opened

the door to the examination of structural gender biases in the labour

market. Since then, there has been a gradual shift in emphasis from

protecting women to promoting equality and improving the living and

working conditions of workers of either sex on an equal basis. It can

be seen, for instance, in the replacement of the Employment (Women

with Family Responsibilities) Recommendation, 1965 (No.123) by the

W.P.(C). No. 3450/2014

-16-

Convention No.156.

24. In the new millennium, new and revised labour standards

reflect the overarching goal of decent work, which now underpins all

the ILOs activity. Gender equality is central to this goal. From the

early 1980s, the focus of analysis concerning equality, in general, was

reoriented from women to relations between women and men. As a

result, the conviction has gained ground that any change in the role

of women should be accompanied by a change in that of men; it

should be reflected in their greater participation in family and

household duties. By this thinking, Convention No. 156 and its

accompanying Recommendation No. 165 concerning workers with

family responsibilities were adopted in 1981. These instruments

apply to men as well as women with responsibilities for dependent

children or other members of their immediate family and are intended

to facilitate their employment without discrimination resulting from

W.P.(C). No. 3450/2014

-17-

such family responsibilities.

25. As per the World Bank statics, by 2010 India had only 19%

of its workforce in non-agricultural sector drawn for women. Indeed,

as a signatory to the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination

against Women (CEDAW) and the UN Convention on the Rights of the

Child (CRC), India has a number of progressive laws that support

gender equality and ending discrimination and violence against

women.

26.

The Government of India was represented at the 2013

session of the Commission on the Status of Women (CSW), where the

Member States committed to ending all forms of violence against

women. They recognized that there was a need to address the

economic and political underpinnings of violence, ensure access to

justice, strengthen multi-sectoral approaches, and end harmful

traditional practices that negatively impact women.

W.P.(C). No. 3450/2014

-18-

27. In Gita Hariharan (supra), the Honble Supreme Court has

observed that India is a signatory to the Convention on the

Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, 1979

("CEDAW") and the Beijing Declaration, which direct all State parties to

take appropriate measures to prevent discrimination of all forms

against women. The domestic courts are under an obligation to give

due regard to International Conventions and Norms for construing

domestic laws when there is no inconsistency between them.

28. Article 15 of the Constitution prohibits discrimination on

grounds of religion, race, caste, sex or place of birth. In fact, Article

15 (1) enjoins a particular application of the general principle of

equality enshrined in Article 14 of the Constitution of India, the

fountainhead of fraternity and equality. While Article 15 (1) mandates

the State in general terms not to indulge in any form of

discrimination, Clause (2) thereof particularises it in relation to the

W.P.(C). No. 3450/2014

-19-

citizens. There is no gainsaying the fact that the combined effect of

Article 14 and 15 of the Constitutin of India does not provide any

blanket ban against passing unequal laws; there can, in fact, be laws

progressively discriminatory. However, the laudability of the objective

behind the seemingly discriminating law does not suffice; on the

other hand, the validity is to be judged by the method of its operation

and its effect on the fundamental rights of a citizen.

It is further

noteworthy that Article 15 (2) is horizontal in its application, thus not

confining itself to the State alone.

29.

As can be seen, Articles 15 (3) & (4) constitute the

exceptions to Articles 15 (1) & (2). Especially Article 15 (3) expressly

permits the State from making any special provision for women and

children. The provision, thus, is in the nature of a proviso qualifying

the general guarantees contained in Arts.14, 15 (1), (2) and 16 (1) &

(2) of the Constitution. There is no cavilling as regards the

W.P.(C). No. 3450/2014

-20-

proposition that the protective discrimination in favour of women

under Article 15 (3) of the Constitution extends to the entire field of

state activity, including that of public employment, which, in fact, has

been specifically dealt with under Article 16 of the Constitution of

India. In essence, the discrimination can be in favour of but not

against the women, whose socio-economic backwardness needs no

further emphasis. Article 15 (3) of the Constitution of India, after all,

is an enabling provision to empower the women.

30. In Govt. of A.P. v. P.B. Vijayakumar,

Vijayakumar 6 the Honble Supreme

Court has examined the importance and the impact of Article 15 (3)

in the backdrop of Articles 15 (1) & (4) and 16 (1) of the Constitution

and has held thus:

7. The insertion of clause (3) of Article 15 in relation to women is a

recognition of the fact that for centuries, women of this country have

been socially and economically handicapped. As a result, they are

unable to participate in the socio-economic activities of the nation on a

footing of equality. It is in order to eliminate this socio-economic

backwardness of women and to empower them in a manner that would

6

(1995) 4 SCC 520

W.P.(C). No. 3450/2014

-21-

bring about effective equality between men and women that Article

15(3) is placed in Article 15. Its object is to strengthen and improve the

status of women. An important limb of this concept of gender equality

is creating job opportunities for women. To say that under Article 15(3),

job opportunities for women cannot be created would be to cut at the

very root of the underlying inspiration behind this article. Making special

provisions for women in respect of employment or posts under the

State is an integral part of Article 15(3). This power conferred under

Article 15(3), is not whittled down in any manner by Article 16.

31. The Court has further observed:

8. What then is meant by any special provision for women in Article

15(3)? This special provision, which the State may make to improve

womens participation in all activities under the supervision and control

of the State can be in the form of either affirmative action or

reservation. It is interesting to note that the same phraseology finds a

place in Article 15(4) which deals with any special provision for the

advancement of any socially or educationally backward class of citizens

or Scheduled Castes or Scheduled Tribes.

32. In Githa Hariharan v. Reserve Bank of India,

India 7 the Apex Court

has referred to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of

Discrimination Against Women, 1979 (CEDAW) and the Beijing

Declaration, which direct all State parties to take appropriate

measures to prevent discrimination of all forms against women.

Acknowledging the fact that India is a signatory to CEDAW having

(1999) 2 SCC 228

W.P.(C). No. 3450/2014

-22-

accepted and ratified it in June 1993, a three-Judge Bench of the

Honble Supreme Court has further observed that the domestic courts

are under an obligation to give due regard to international

conventions and norms for construing domestic laws when there is no

inconsistency between them.

Anuj Garg:

33. In Anuj Garg v. Hotel Assn. of India,

India (2008) 3 SCC 1, what

fell for consideration was the Constitutional validity of Section 30 of

the Punjab Excise Act, 1914 prohibiting employment of any man

under the age of 25 years or any woman in any part of such

premises in which the public consume liquor or intoxicating drug.

The Court has observed that right to be considered for employment

subject to just exceptions is recognised by Article 16 of the

Constitution. Right of employment itself may not be a fundamental

right but in terms of both Articles 14 and 16 of the Constitution of

W.P.(C). No. 3450/2014

-23-

India, each person similarly situated has a fundamental right to be

considered therefor.

34.

As regards the ascendancy of women in the sphere of

public employment, the Apex Court has observed that when a

discrimination is sought to be made on the purported ground of

classification, such classification must be founded on rational criteria.

The criteria in the absence of any constitutional provision and, it will

bear repetition to state, having regard to the societal conditions as

they prevailed in early 20th century, may not be a rational criteria in

the 21st century. In the early 20th century, the hospitality sector was

not open to women in general. In the last 60 years, women in India

have gained entry in all spheres of public life. They have also been

representing

people

at

grassroots

democracy.

They

are

now

employed as drivers of heavy transport vehicles, conductors of service

carriages, police etc. Women can be seen to be occupying Class IV

W.P.(C). No. 3450/2014

-24-

posts to the post of a Chief Executive Officer of a multinational

company. They are now widely accepted both in the Police as also

Army services.

35.

Eventually, examining what is said to be fundamental

tension between right to employment and security, their Lordships

have held as follows:

34. The fundamental tension between autonomy and security is

difficult to resolve. It is also a tricky jurisprudential issue. Right to selfdetermination is an important offshoot of gender justice discourse. At

the same time, security and protection to carry out such choice or

option specifically, and state of violence-free being generally is another

tenet of the same movement. In fact, the latter is apparently a more

basic value in comparison to right to options in the feminist matrix.

35. Privacy rights prescribe autonomy to choose profession whereas

security concerns texture methodology of delivery of this assurance. But

it is a reasonable proposition that the measures to safeguard such a

guarantee of autonomy should not be so strong that the essence of the

guarantee is lost. State protection must not translate into censorship.

36. At the same time we do not intend to further the rhetoric of

empty rights. Women would be as vulnerable without State protection

as by the loss of freedom because of the impugned Act. The present

law ends up victimising its subject in the name of protection. In that

regard the interference prescribed by the State for pursuing the ends of

protection should be proportionate to the legitimate aims. The standard

for judging the proportionality should be a standard capable of being

called reasonable in a modern democratic society.

37. Instead of putting curbs on womens freedom, empowerment

would be a more tenable and socially wise approach. This

empowerment should reflect in the law enforcement strategies of the

W.P.(C). No. 3450/2014

-25-

State as well as law modelling done in this behalf.

38. Also with the advent of modern State, new models of security

must be developed. There can be a setting where the cost of security in

the establishment can be distributed between the State and the

employer.

(emphasis original)

36. As to the constitutional validity of Section 30 of the Act, the

Court has observed that its task is to determine whether the

measures furthered by the State in the form of legislative mandate to

augment the legitimate aim of protecting the interests of women are

proportionate to the other bulk of well-settled gender norms such as

autonomy, equality of opportunity, right to privacy, etc. The bottom

line in this behalf would be a functioning modern democratic society

which ensures freedom to pursue varied opportunities and options

without discriminating on the basis of sex, race, caste or any other

like basis. In fine, there should be a reasonable relationship of

proportionality between the means used and the aim pursued.

37.

Eventually, the Court has quoted with approval the

W.P.(C). No. 3450/2014

-26-

peroration of Ginsburg, J., in United States v. Virginia8, which is

worthy of reproduction, and which reads as follows:

The heightened review standard our precedent establishes does not

make sex a proscribed classification. Supposed inherent differences are

no longer accepted as a ground for race or national origin

classifications. Physical differences between men and women, however,

are enduring. Inherent differences between men and women, we have

come to appreciate, remain cause for celebration, but not for

denigration of the members of either sex or for artificial constraints on

an individuals opportunity. Sex classifications may be used to

compensate women for particular economic disabilities [they have]

suffered, to promote equal employment opportunity, to advance full

development of the talent and capacities of our nations people. But

such classifications may not be used, as they once were, to create or

perpetuate the legal, social, and economic inferiority of women.

(as quoted in Anuj Garg (supra)

38. The upshot of the above disposition in Anuj Garg is that the

Honble Supreme Court has affirmed the judgment of the Honble

Punjab & Haryana High Court, which declared Section 30 of the

Punjab Excise Act, 1914 unconstitutional.

39. This Court as far back as in 1976 has held in an unreported

judgment in O.P. No.5080 of 1976 to the following effect:

We in this country carry with us, to a considerable extent, our

conventional thinking and attitude to social life despite modern trends in

8

518 US 515 (1996)

W.P.(C). No. 3450/2014

-27-

the approach to individual freedom and right to equality. Our people,

and particularly the Hindus and the Muslims who constitute a large

proportion of the population have been conditioned over a long period

of time to view woman as subordinate to the authority of her man, as

one not equal to man in physical prowess and capacity for physical

endurance. The Constitution of our nation reflects civilized thinking and

assures women their rightful place as citizens of this country. But

despite such solemn guarantee there are many areas where she has yet

to gain equality with the male. Despite resolutions at International

Conferences highlighting the need for a fairer treatment to the fair sex

there are areas where law has not still stepped in to remove the

disabilities of women and the anomalies in the social set up. We have

recently observed the International Year of the Women but its impact,

in terms of positive gains is yet to be assessed.

(as quoted in A. S. Rajamma (infra)

40. In A. S. Rajamma v. State of Kerala9, the issue is concerning

denial of appointment of women candidates in the select list for

appointment in the last grade service on the ground that they are

women incapable of performing arduous physical tasks. Having

observed that not much of case law in the Indian Courts on the

question of discrimination against women is available, a learned

Division Bench of this Court, after referring to copious case of

American and English Courts, has held as follows:

34. Remembering what the practical consequence of the attitude of

9

1983 KLT 457

W.P.(C). No. 3450/2014

-28-

the Government has been, namely that for one reason or other not a

single woman has been advised to any one of the 260 posts we find

that this is a clear case of discrimination, a discrimination which falls not

within Article 14 of the Constitution only, but also within the specific

prohibition in Article 15(1) of the Constitution. The mandate to the

State that it shall not discriminate against any citizen on grounds only of

sex is one of the most important fundamental rules that calls for strict

observance. In the framing of any statute or law or the making of

subordinate legislation by a delegated legislative authority this is a

fundamental rule which, under no circumstances, would bear violation.

Unlike the freedoms in Article 19 of the Constitution there is no Scope

for restricting the absolute scope of the rights under Article 15(1) of the

Constitution. There would be no scope whatever to justify

differentiating between the male and female sexes in the matter of

appointment. The right of women should not be denied on fanciful

assumptions of what work the woman could do and could not do.

Whether the work is of an arduous nature and, therefore, unsuitable for

women must be decided from the point of view of how women feel

about it and how they would assess it

41. It needs no much cogitation to hold that Rule 27A of Kerala

Foreign Liquor Rules as well as condition 9 A under the head

Conditions in Forms FL 3 fall foul of the Constitutional scheme of

gender equality as has been spelt out in Articles 14, 15 (1) & (2) and

16 (1) & (2) of the Constitution of India. It is accordingly held.

As a result, the writ petition is allowed. No order as to costs.

W.P.(C). No. 3450/2014

-29-

sd/sd/- DAMA SESHADRI NAIDU, JUDGE.

rv

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Maharashtra - The Inter-State Migrant Workmen (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) (Maharashtra) Rules, 1985Dokument26 SeitenMaharashtra - The Inter-State Migrant Workmen (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) (Maharashtra) Rules, 1985Ayesha AlwareNoch keine Bewertungen

- Joining Kit All FormsDokument13 SeitenJoining Kit All FormsgopamaheshwariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Appointment Reciept SHOEBDokument2 SeitenAppointment Reciept SHOEBNil OnlyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Regulatory Barriers To Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises: Amit Chandra & Vrinda Pareek Centre For Civil SocietyDokument71 SeitenRegulatory Barriers To Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises: Amit Chandra & Vrinda Pareek Centre For Civil SocietyAnkitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Amazing - Dapoli Detailed MapDokument1 SeiteAmazing - Dapoli Detailed MapShekar KNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abstract of Minimum Wages ActDokument7 SeitenAbstract of Minimum Wages ActManikanta SatishNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sadhana Infotech #335, 19th Main, Rajaji Nagar, 1st Block, Bangalore-560010Dokument1 SeiteSadhana Infotech #335, 19th Main, Rajaji Nagar, 1st Block, Bangalore-560010Shreekant SkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Temporary Identity CertificateDokument1 SeiteTemporary Identity CertificateSuman61% (18)

- HCL Technologies: Performance HighlightsDokument15 SeitenHCL Technologies: Performance HighlightsAngel BrokingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Study of HRM Practices On Employees Retention: A Review of LiteratureDokument8 SeitenStudy of HRM Practices On Employees Retention: A Review of LiteratureReny NapitupuluNoch keine Bewertungen

- Minimum Wages Karnataka Rules 1958Dokument35 SeitenMinimum Wages Karnataka Rules 1958rukmavva chavanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Recruitment Selection - HandoutDokument8 SeitenRecruitment Selection - HandoutahetasamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ags Offer LetterDokument10 SeitenAgs Offer LetterMaathesh TraderNoch keine Bewertungen

- DT20184848101 PDFDokument9 SeitenDT20184848101 PDFasra naazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Form 16: Wipro LimitedDokument5 SeitenForm 16: Wipro LimitedIbrahim MohammadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jitendra Raghuwanshi - ATCS Offer Letter - 7th February 2020Dokument4 SeitenJitendra Raghuwanshi - ATCS Offer Letter - 7th February 2020Sonam BhardwajNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letter of Intent Rahul TiwariDokument1 SeiteLetter of Intent Rahul TiwariRAHUL TIWARINoch keine Bewertungen

- Presentation Made To Analysts / Investors (Company Update)Dokument20 SeitenPresentation Made To Analysts / Investors (Company Update)Shyam SunderNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Maharashtra Labour Welfare Fund Act, 1953: D.R. Haibat Corporate Consultant and Consulting Lawyer NGO MemberDokument10 SeitenThe Maharashtra Labour Welfare Fund Act, 1953: D.R. Haibat Corporate Consultant and Consulting Lawyer NGO MemberDeepakNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ruby General Hospital LTDDokument1 SeiteRuby General Hospital LTDSaurav PeriwalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Salary SlipDokument1 SeiteSalary SlipEr Sailesh PaudelNoch keine Bewertungen

- CWR Joining Booklet - Personal Details VishnuDokument6 SeitenCWR Joining Booklet - Personal Details VishnuVishnuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Offer Letter - Komal SharmaDokument6 SeitenOffer Letter - Komal SharmaHIMANI RANANoch keine Bewertungen

- Open Narige Prashanth Kumar Offer LetterDokument7 SeitenOpen Narige Prashanth Kumar Offer Letterrajashekar.nallapati7036Noch keine Bewertungen

- Airtel Recruitment and Selection PDFDokument11 SeitenAirtel Recruitment and Selection PDFEr Bhatt Dhruvi0% (1)

- Bank Offer Letter RawaliDokument3 SeitenBank Offer Letter RawaliAnurag SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Deed of TrustDokument19 SeitenDeed of Trustshakhawat_cNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kotak Mahindra (3719)Dokument2 SeitenKotak Mahindra (3719)Sagar PandeyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letter of Offer WiproDokument52 SeitenLetter of Offer WiproSauvik BhattacharyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Certificate of IncorporationDokument1 SeiteCertificate of IncorporationVivek DixitNoch keine Bewertungen

- AprilDokument1 SeiteAprilabhinavbartarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Offer LetterDokument1 SeiteOffer LetterRajesh PaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Star Health Offer LetterDokument1 SeiteStar Health Offer LetterPARVEEN CHAHAR0% (1)

- Cyber Café and Xerox Lamination: Profile No.: 6 NIC Code: 63992Dokument6 SeitenCyber Café and Xerox Lamination: Profile No.: 6 NIC Code: 63992EdigitalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Q2 AbDokument6 SeitenQ2 AbDhiraj YAdavNoch keine Bewertungen

- Indian Income Tax Return Acknowledgement: Do Not Send This Acknowledgement To CPC, BengaluruDokument1 SeiteIndian Income Tax Return Acknowledgement: Do Not Send This Acknowledgement To CPC, BengaluruRoshanjit ThakurNoch keine Bewertungen

- Telephone Number: +91 141 267 0101, Facsimile Number: +91 141 267 0303 Amber Fort Road, Opposite Jal Mahal, Jaipur, 302002, IndiaDokument3 SeitenTelephone Number: +91 141 267 0101, Facsimile Number: +91 141 267 0303 Amber Fort Road, Opposite Jal Mahal, Jaipur, 302002, IndiaRamnish MishraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sip Pallavi 21Dokument21 SeitenSip Pallavi 21Vickey KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Infosys Offer LetterDokument2 SeitenInfosys Offer LetterABTNNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Appraisal Letter) (1) - 1Dokument1 Seite(Appraisal Letter) (1) - 1rishuNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Project Report ON "A Study On Selection Process Adopted by Tata Constancy Services "Dokument35 SeitenA Project Report ON "A Study On Selection Process Adopted by Tata Constancy Services "Shantanu Kirpane100% (1)

- Mr. Pankaj Kumar Tyagi APLDokument8 SeitenMr. Pankaj Kumar Tyagi APLRashi SrivastavaNoch keine Bewertungen

- SBI Compensation Policy 2018Dokument21 SeitenSBI Compensation Policy 2018fictional worldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Offerletter 369844Dokument24 SeitenOfferletter 369844Gokul GandhiNoch keine Bewertungen

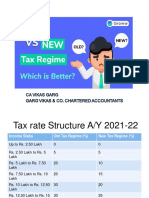

- Old Vs New Tax RegimeDokument9 SeitenOld Vs New Tax Regimescintillating26Noch keine Bewertungen

- BV Consent Form - TechM - N PDFDokument1 SeiteBV Consent Form - TechM - N PDFpankajNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sata Globe BPM PVT LTD: Offer LatterDokument4 SeitenSata Globe BPM PVT LTD: Offer LatterSachin ShahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Job No.: #67123: National Highways Authority of IndiaDokument34 SeitenJob No.: #67123: National Highways Authority of IndiaBal RajNoch keine Bewertungen

- Work Experience KFCDokument1 SeiteWork Experience KFCsham_code0% (1)

- Ref: "Maruti Suzuki" Direct Recruitments Offer.: (10:00 Am To 5:30 PM) Speak English Only or Send SmsDokument2 SeitenRef: "Maruti Suzuki" Direct Recruitments Offer.: (10:00 Am To 5:30 PM) Speak English Only or Send SmsSumit Malhotra0% (1)

- Statutory Compliances of A Manufacturing IndustryDokument27 SeitenStatutory Compliances of A Manufacturing IndustrySiddharth Kumar0% (1)

- Abstract Under Karnataka Shops and Commercial Establishment Rules, 1963Dokument2 SeitenAbstract Under Karnataka Shops and Commercial Establishment Rules, 1963AsokNoch keine Bewertungen

- 04 Soniya Guna Seelan Offer LetterDokument3 Seiten04 Soniya Guna Seelan Offer LetterawsrestartsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kushal Gupta Offer Letter25772Dokument3 SeitenKushal Gupta Offer Letter25772Kushal GuptaNoch keine Bewertungen

- IDFC FIRST Bank Letter of Appointment Along With Model Terms and ConditionsDokument6 SeitenIDFC FIRST Bank Letter of Appointment Along With Model Terms and ConditionsSidharth patraNoch keine Bewertungen

- The New Labour CodesDokument15 SeitenThe New Labour CodesDhananjay SinghalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Annual Report 2017 18Dokument324 SeitenAnnual Report 2017 18bhupeshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurisdiction Compilation of Case Digest: Submitted By: Olidan, Mariea CDokument72 SeitenJurisdiction Compilation of Case Digest: Submitted By: Olidan, Mariea CMariea OlidanNoch keine Bewertungen

- SC Gamca Ruling 2015Dokument8 SeitenSC Gamca Ruling 2015Maris Angelica AyuyaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Association of Medical Clinics For Overseas Workers, Inc. v. GCC Approved Medical Centers Association, Inc., - Chapter 3 - SOVEREIGNTYDokument2 SeitenAssociation of Medical Clinics For Overseas Workers, Inc. v. GCC Approved Medical Centers Association, Inc., - Chapter 3 - SOVEREIGNTYrian5852Noch keine Bewertungen

- Shakil Ahmad Jalaluddin Shaikh vs. Vahida Shakil ShaikhDokument11 SeitenShakil Ahmad Jalaluddin Shaikh vs. Vahida Shakil ShaikhLive Law100% (1)

- Strict Action Against Errant Docs, Tab On Diagnostic Centres Must To Curb Female Foeticide: Panel To SCDokument29 SeitenStrict Action Against Errant Docs, Tab On Diagnostic Centres Must To Curb Female Foeticide: Panel To SCLive Law100% (1)

- Bombay HC Asks Errant Police Officers To Pay Compensation To Doctors For Their Illegal Detention' in A Bailable CrimeDokument25 SeitenBombay HC Asks Errant Police Officers To Pay Compensation To Doctors For Their Illegal Detention' in A Bailable CrimeLive Law100% (1)

- Bombay HC Exonerates Two Senior Advocates From Allegations of Misrepresenting Facts Issues Contempt Notices Against Advocates Who Made The AllegationsDokument51 SeitenBombay HC Exonerates Two Senior Advocates From Allegations of Misrepresenting Facts Issues Contempt Notices Against Advocates Who Made The AllegationsLive LawNoch keine Bewertungen

- SanctionDokument127 SeitenSanctionLive LawNoch keine Bewertungen

- Delhi High Court Releases A Rape' Convict As He Married The VictimDokument5 SeitenDelhi High Court Releases A Rape' Convict As He Married The VictimLive Law100% (1)

- Defence EQuipmentDokument15 SeitenDefence EQuipmentLive LawNoch keine Bewertungen

- Filing Vague and Irrelevant RTI QueriesDokument15 SeitenFiling Vague and Irrelevant RTI QueriesLive LawNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prosecute Litigants Who Indulge in Filing False Claims in Courts Invoking Section 209 IPC - Delhi HC PDFDokument99 SeitenProsecute Litigants Who Indulge in Filing False Claims in Courts Invoking Section 209 IPC - Delhi HC PDFLive Law100% (1)

- Husband Filing Divorce Petition Is No Justification For Wife To Lodge False Criminal Cases Against Him and His Family - Bombay HCDokument81 SeitenHusband Filing Divorce Petition Is No Justification For Wife To Lodge False Criminal Cases Against Him and His Family - Bombay HCLive Law100% (3)

- Arundhati Roy SLPDokument61 SeitenArundhati Roy SLPLive Law0% (1)

- Compassionate AppointmentDokument19 SeitenCompassionate AppointmentLive LawNoch keine Bewertungen

- IP ConfrenceDokument1 SeiteIP ConfrenceLive LawNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nankaunoo Vs State of UPDokument10 SeitenNankaunoo Vs State of UPLive LawNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lifting Corporate VeilDokument28 SeitenLifting Corporate VeilLive LawNoch keine Bewertungen

- CPIL Submissions On CJI's Remark Revised - 2Dokument16 SeitenCPIL Submissions On CJI's Remark Revised - 2Live LawNoch keine Bewertungen

- Surender at Kala vs. State of HaryanaDokument9 SeitenSurender at Kala vs. State of HaryanaLive LawNoch keine Bewertungen

- DowryDokument11 SeitenDowryLive Law50% (2)

- Sarfaesi ActDokument40 SeitenSarfaesi ActLive Law100% (2)

- WWW - Livelaw.In: Bella Arakatsanis Agner Ascon and ÔTÉDokument13 SeitenWWW - Livelaw.In: Bella Arakatsanis Agner Ascon and ÔTÉLive LawNoch keine Bewertungen

- Answersheets - RTIDokument21 SeitenAnswersheets - RTILive LawNoch keine Bewertungen

- Allahabad HCDokument18 SeitenAllahabad HCLive LawNoch keine Bewertungen

- GazetteDokument1 SeiteGazetteLive Law100% (1)

- SabarimalaDokument4 SeitenSabarimalaLive LawNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comedy NightsDokument2 SeitenComedy NightsLive LawNoch keine Bewertungen

- CPIL Resolution 2013Dokument1 SeiteCPIL Resolution 2013Live LawNoch keine Bewertungen

- Condom Is Not A Medicine: Madras High CourtDokument8 SeitenCondom Is Not A Medicine: Madras High CourtLive LawNoch keine Bewertungen

- Realistic Costs Should Be Imposed To Discourage Frivolous LitigationsDokument173 SeitenRealistic Costs Should Be Imposed To Discourage Frivolous LitigationsLive LawNoch keine Bewertungen

- Delhi High Court Act, 2015Dokument2 SeitenDelhi High Court Act, 2015Live LawNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ermita Manila Hotel v. City of Manila GR No. L 24693 July 31 1967Dokument7 SeitenErmita Manila Hotel v. City of Manila GR No. L 24693 July 31 1967Christine Rose Bonilla LikiganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bar Questions Answers. Set 34Dokument3 SeitenBar Questions Answers. Set 34cjadapNoch keine Bewertungen

- Appen Digital Signature RequiredDokument4 SeitenAppen Digital Signature RequiredMichael GirayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Republic Act 7438 Senate Explanatory NoteDokument8 SeitenRepublic Act 7438 Senate Explanatory NoteFaye Cience BoholNoch keine Bewertungen

- Act No. 2031Dokument25 SeitenAct No. 2031Jannina Pinson RanceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Law Society of British Columbia v. Currie, (Dokument5 SeitenLaw Society of British Columbia v. Currie, (Kevin GraceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Catalino Gallemit, vs. Ceferino Tabiliran: FactsDokument1 SeiteCatalino Gallemit, vs. Ceferino Tabiliran: Factsjeljeljelejel arnettarnettNoch keine Bewertungen

- ETHICSDokument23 SeitenETHICSLovely De CastroNoch keine Bewertungen

- AGORA International Journal of Juridical Sciences: WWW - Juridicaljournal.univagoraDokument259 SeitenAGORA International Journal of Juridical Sciences: WWW - Juridicaljournal.univagoradana_danny1789Noch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Communications Vs Alcuaz DigestDokument1 SeitePhilippine Communications Vs Alcuaz DigestEbbe DyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Injunction in MalaysiaDokument2 SeitenInjunction in MalaysiaRaider100% (13)

- Vda de Reyes Vs CADokument4 SeitenVda de Reyes Vs CAMaria Cherrylen Castor QuijadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sales ReviewerDokument29 SeitenSales ReviewerHoward Chan95% (21)

- The Establishment Clause of The First Amendment: It's History, Legal Interpretations and ApplicationsDokument12 SeitenThe Establishment Clause of The First Amendment: It's History, Legal Interpretations and Applicationsapi-298947470Noch keine Bewertungen

- Act/ Omission in Flarante Delicto Hot Pursuit Filed in Court Arrest Bail Preliminary ConferenceDokument4 SeitenAct/ Omission in Flarante Delicto Hot Pursuit Filed in Court Arrest Bail Preliminary ConferenceAndrea IvanneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Yuchico vs. Atty. Gutierrez, A.C. No. 8391, Nov. 23, 2010Dokument5 SeitenYuchico vs. Atty. Gutierrez, A.C. No. 8391, Nov. 23, 2010Tim SangalangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Digest Quintanar vs. Coca-ColaDokument2 SeitenCase Digest Quintanar vs. Coca-ColaMaria Anna M Legaspi100% (1)

- 34 64621Dokument3 Seiten34 64621Pamela-Jo RefuerzoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Polson Answer To Linlor ComplaintDokument8 SeitenPolson Answer To Linlor ComplaintLaw&CrimeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Silahis Hotel Vs Rogelio SolutaDokument12 SeitenSilahis Hotel Vs Rogelio SolutaMctabs TabiliranNoch keine Bewertungen

- National Cyber Security in PakistanDokument73 SeitenNational Cyber Security in PakistanShahid Jamal TubrazyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nationality Card 3.5 by 2.25Dokument2 SeitenNationality Card 3.5 by 2.25Ilataza Ban Yasharahla -El80% (5)

- Land Titles and Deeds NotesDokument16 SeitenLand Titles and Deeds NotesdayneblazeNoch keine Bewertungen

- #Domondon V NLRCDokument2 Seiten#Domondon V NLRCKareen Baucan100% (1)

- Win in Court EverytimeDokument26 SeitenWin in Court Everytimeohbabyohbaby100% (14)

- Summary of Arguments by Caney and BeitzDokument11 SeitenSummary of Arguments by Caney and BeitzAVNoch keine Bewertungen

- 04b TOM Taxation Law Bar Reviewer - Pages PDFDokument395 Seiten04b TOM Taxation Law Bar Reviewer - Pages PDFLucas MenteNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5 Locsin Vs MekeniDokument2 Seiten5 Locsin Vs MekeniWendell Leigh Oasan100% (3)

- Writ of Continuing MandamusDokument2 SeitenWrit of Continuing MandamusGretchin CincoNoch keine Bewertungen

- SAMPLE MOtion For ReleaseDokument3 SeitenSAMPLE MOtion For Releaseczabina fatima delicaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unwanted Advances: Sexual Paranoia Comes to CampusVon EverandUnwanted Advances: Sexual Paranoia Comes to CampusBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (22)

- Never Chase Men Again: 38 Dating Secrets to Get the Guy, Keep Him Interested, and Prevent Dead-End RelationshipsVon EverandNever Chase Men Again: 38 Dating Secrets to Get the Guy, Keep Him Interested, and Prevent Dead-End RelationshipsBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (387)

- The Masonic Myth: Unlocking the Truth About the Symbols, the Secret Rites, and the History of FreemasonryVon EverandThe Masonic Myth: Unlocking the Truth About the Symbols, the Secret Rites, and the History of FreemasonryBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (14)

- Lucky Child: A Daughter of Cambodia Reunites with the Sister She Left BehindVon EverandLucky Child: A Daughter of Cambodia Reunites with the Sister She Left BehindBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (54)

- The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and LoveVon EverandThe Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and LoveBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (383)

- Unlikeable Female Characters: The Women Pop Culture Wants You to HateVon EverandUnlikeable Female Characters: The Women Pop Culture Wants You to HateBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (18)

- For the Love of Men: From Toxic to a More Mindful MasculinityVon EverandFor the Love of Men: From Toxic to a More Mindful MasculinityBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (56)

- Sex and the City and Us: How Four Single Women Changed the Way We Think, Live, and LoveVon EverandSex and the City and Us: How Four Single Women Changed the Way We Think, Live, and LoveBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (22)

- Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of PlantsVon EverandBraiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of PlantsBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (1423)

- You Can Thrive After Narcissistic Abuse: The #1 System for Recovering from Toxic RelationshipsVon EverandYou Can Thrive After Narcissistic Abuse: The #1 System for Recovering from Toxic RelationshipsBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (16)

- Sexual Ethics and Islam: Feminist Reflections on Qur'an, Hadith, and JurisprudenceVon EverandSexual Ethics and Islam: Feminist Reflections on Qur'an, Hadith, and JurisprudenceBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (8)

- Fallen Idols: A Century of Screen Sex ScandalsVon EverandFallen Idols: A Century of Screen Sex ScandalsBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (7)

- Summary: Fair Play: A Game-Changing Solution for When You Have Too Much to Do (and More Life to Live) by Eve Rodsky: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedVon EverandSummary: Fair Play: A Game-Changing Solution for When You Have Too Much to Do (and More Life to Live) by Eve Rodsky: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Tears of the Silenced: An Amish True Crime Memoir of Childhood Sexual Abuse, Brutal Betrayal, and Ultimate SurvivalVon EverandTears of the Silenced: An Amish True Crime Memoir of Childhood Sexual Abuse, Brutal Betrayal, and Ultimate SurvivalBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (136)

- Unbound: My Story of Liberation and the Birth of the Me Too MovementVon EverandUnbound: My Story of Liberation and the Birth of the Me Too MovementBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (147)

- Decolonizing Wellness: A QTBIPOC-Centered Guide to Escape the Diet Trap, Heal Your Self-Image, and Achieve Body LiberationVon EverandDecolonizing Wellness: A QTBIPOC-Centered Guide to Escape the Diet Trap, Heal Your Self-Image, and Achieve Body LiberationBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (22)

- Not That Bad: Dispatches from Rape CultureVon EverandNot That Bad: Dispatches from Rape CultureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (341)

- Feminine Consciousness, Archetypes, and Addiction to PerfectionVon EverandFeminine Consciousness, Archetypes, and Addiction to PerfectionBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (89)

- Why the Jews?: The Reason for AntisemitismVon EverandWhy the Jews?: The Reason for AntisemitismBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (37)