Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

North Carolina's Letter To EPA

Hochgeladen von

Jon OstendorffOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

North Carolina's Letter To EPA

Hochgeladen von

Jon OstendorffCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

January 11, 2015

Heather McTeer Toney

Regional Administrator

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Region 4

61 Forsyth Street, SW

Atlanta, GA 30303

RE: Standards for Judicial Review

Dear Ms. Toney:

I write in reference to your Oct. 30, 2015, letter expressing concern that citizens access to

judicial review has become unduly restrictive in North Carolina. Frankly, I was surprised by the

letter, as North Carolina has historically and consistently provided judicial access to citizens

beyond what is required or afforded by federal law. North Carolina recognizes the important role

our citizens play in protecting the environment. We will continue to protect the publics voice in

the permitting process. Interestingly, a comparison between federal and North Carolina

requirements to challenge an environmental permit indicates that the federal governments

standard is more restrictive than the opportunities afforded to North Carolina citizens.

In your letter, you cite two ongoing cases regarding permits issued by the North Carolina

Department of Environmental Quality, or NCDEQ. Consistent with regulations and agreements,

we provided your agency with draft permits for your review. In neither case did your staff object

to the permits nor did they identify any inconsistencies with the Clean Water Act (CWA) or

Clean Air Act (CAA). Of course, your approval does not mean that additional input from the

public should be ignored.

With respect to third party challenges, your letter raised the issue of whether North Carolina

provides judicial access to third parties consistent with requirements under the CWA and the

CAA. When EPA approved our permitting authority, it had reviewed our programs and agreed

that North Carolina law satisfies the minimum federal requirements related to judicial review.

With respect to the Title V program under the CAA, you based your approval, in part, on

representations made in our 1993 Attorney Generals opinion. However, your letter cites two

ongoing cases that you believe do not satisfy EPA requirements for access to the courts. I

believe your concerns are unfounded for the following reasons.

Heather McTeer Toney

January 11, 2016

Page 2

1) You appear to misunderstand how the North Carolina Attorney General and our judges

interpreted North Carolina laws. Below you will find what our Attorney Generals office

said, both in the past when discussing third party rights in North Carolina, as well as what

it argued in the Carolinas Cement case (N.C. Coastal Fedn v. N.C. Dept of Envt & Natural

Res., 12 EHR 02850 (NCOAH, Sept. 23, 2013)). We also include an excerpt from Judge

Beecher Gray, a pre-eminent expert in administrative law, generally, and third party

appeal rights, in particular. The statements made by our Attorney Generals office and the

judge are consistent and differ from the interpretation your letter presented. We

recognize that your interpretation may have been urged by a special interest advocacy

group, but we would encourage you to objectively review what those officials charged

with interpreting our laws had said.

2) The cases you cited actually illustrate that North Carolina provides third parties with fair

and ample access to judicial review. In the Carolinas Cement case, the third party

challenger was actually granted judicial review but ultimately failed to establish an

element of their claim. In the Martin Marietta case (Sound Rivers. v. N.C. Dept of Envt

& Natural Res., 15 CVS 262 (Sup. Ct., Nov. 9, 2015)), the Superior Court remanded the

case after finding that the administrative law judge erroneously denied standing to the

third party challenger, illustrating that North Carolina law indeed provides third parties

access to the courts.

North Carolina goes beyond the federal minimum elements required for program approval with

respect to access to the courts. On the specific question of public participation in

CAA/Prevention of Significant Deterioration (PSD) permitting, North Carolina provides third

parties with access to judicial review irrespective of the fact that such access is not required as a

minimum element of PSD program approval. See 40 CFR 51.166. In contrast, both the

CAA/Title V program and the CWA/National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES)

permitting programs explicitly require third party access to the courts. There has been confusion

on this difference, but North Carolinas laws provide for third party access to judicial review

even in the PSD program. This is an important point and, while it may not be recognized by

some academic observers, it further illustrates how North Carolinas provisions for citizen access

and participation go beyond federal minimums.1

The following provides a brief discussion of the relevant North Carolina statutes and uses the

two cases you cited to illustrate how North Carolina law provides access to judicial review for

third parties. Our review of the federal process determined that the federal process is more

restrictive than any of the CWA and Title V minimum elements and, therefore, restricts the

ability of citizens to challenge federal permits.

This confusion may stem from an Environmental Appeals Board case where the issue of whether the minimum

elements for an approvable PSD program included judicial review. The only support EPA offered for an affirmative

response was reference to a case involving only Title V and did not reference PSD permitting.

Heather McTeer Toney

January 11, 2016

Page 3

Citizen Access under North Carolina Law

North Carolinas Administrative Procedure Act (NC APA) was initially adopted in 1974 and

provided person[s] aggrieved access to judicial review without regard as to whether those

persons are third parties. North Carolinas NPDES program was initially approved by the EPA

in 1975. At that time, North Carolina provided citizen access to judicial review through the NC

APA despite the fact that EPA regulations did not require states to provide judicial review for

approval. Not for another 19 years did your agency revise the minimum elements for approval to

include a requirement for judicial review. Your amended regulation provided that a state

[m]ust provide an opportunity for judicial review in State court of the final approval

or denial of permits by the State that is sufficient to provide for, encourage, and

assist public participation in the permitting process. A State will meet this standard

if State law allows an opportunity for judicial review that is the same as that

available to obtain judicial review in federal court of a federally-issued NPDES

permit. A state will not meet this standard if it narrowly restricts the class of persons

who may challenge the approval or denial of permits (for example, if only the

permittee can obtain judicial review, if persons must demonstrate a pecuniary

interest in order to obtain judicial review, or if persons must have a property interest

in close proximity to a discharge or surface waters in order to obtain judicial

review.) 40 CFR 123.30 (emphasis added).

This language provides a general standard for evaluating state programs and includes examples

of state rules that are presumptively acceptable and those that are not. In 2009, your agency

stated in federal court that [n]othing in the CWA or EPAs regulations requires state programs

to provide the same opportunity for judicial review of permitting decisions as is required for

federally issued permits. Instead, EPAs regulations adopt the standards set forth in the CWA:

state programs must provide an opportunity for judicial review sufficient to promote, assist, and

encourage public participation in the permitting process.2

In proposing to approve North Carolinas Title V permit program under the CAA, the EPA

determined that the North Carolina Attorney Generals opinion submitted on behalf of North

Carolina adequately address[es] the thirteen provisions listed at 40 CFR 70.4(b)(3)(i)-(xiii). 60

FR 44805 (August 29, 1995) (final interim approval at 60 FR 57357 (November 15, 1995)

including the requirement to provide citizen access to judicial review). The North Carolina

Attorney General specifically addressed judicial review and stated that

[t]he limitation on access to judicial review in those provisions is certainly not more

restrictive, and is in all likelihood less restrictive than the standing requirements of

Article III of the United States Constitution. The state statute granting the right to

2

Brief of Appellee-Respondent at 13-14, Akiak Native Comm et al. v. US EPA, et al., No. 08-74872 (9th Cir. Aug.

21, 2009)

Heather McTeer Toney

January 11, 2016

Page 4

judicial review, G.S. 143-215.5(b) grants the right to all person[s] aggrieved by

the final permit decision. Person aggrieved is defined in G.S. 150B-2 to mean

any person or group of persons of common interest directly or indirectly affected

substantially in his or its person, property, or employment by an administrative

decision. This is at least as broad as the minimal standing requirements of Article

III enunciated by the U.S. Supreme Court in Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife, 504

U.S. 555, 112 S. Ct. 2130 (1992). Therefore, it is the opinion of this office that the

limitations on access to judicial review contained in G.S. 143-215.5(b) and the

standing requirements embodied in the term person aggrieved do not exceed the

corresponding limits on judicial review imposed by the standing requirements of

Article III of the United States Constitution.

North Carolina Attorney Generals statement (November 5, 1993) at 14-15. This opinion

confirms that the right to judicial review under the CAA/Title V program turns on

person aggrieved and that this standard is at least as broad as Article III.

Federal Citizen Access

The EPAs Environmental Appeals Board (EAB) is a federal administrative forum in which

remedies must be exhausted as a prerequisite for access to the courts and is comparable to North

Carolinas Office of Administrative Hearings (OAH), which is the state administrative forum.

This is one respect, among others, in which EAB is analogous to OAH, but there are also

differences perhaps more striking than the similarities:

The hearing officers at the EAB are EPA employees, whereas the Administrative Law

Judges of OAH are appointed by the Chief Justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court

and are independent of the Department of Environmental Quality.

Review before the EAB is available to any interested person. The term interested

person is not defined, but it repeats the term used at Section 509 of the Clean Water Act

which provides for judicial review of permits in the Court of Appeals (the term is absent

from Section 307 of the CAA). The use of the term in the CAA context strongly suggests

that an interested person is one who satisfies the requirements of Article III standing.

Were that not the case, the interested person who had her case heard by the EAB might

not be able to get review in the Court of Appeals for lack of standing. Review in OAH

and state courts is available to any person aggrieved, as discussed and defined, supra.

There are, apparently, under EPA rules, two barriers for interested persons to access

judicial review. A petitioner who filed comments on the draft permit or participated in

the public hearing may petition the EAB to review any condition of the permit decision.

However, if a person failed to provide, in sufficient detail, why EPAs responses to

comments were irrelevant, erroneous, insufficient, or an abuse of discretion, irrespective

of whether that person has a demonstrable pecuniary or property interest, that person may

petition for review only to the extent of the changes from the draft to the final permit

decision. Unlike the EPA rules, which could deny judicial review to a person who

Heather McTeer Toney

January 11, 2016

Page 5

otherwise had Article III standing, there are no threshold requirements under North

Carolina law for a petitioner to have participated in the review or comment period in

order to challenge a permit. Any permit applicant, permittee, or third party who is

dissatisfied with a decision to issue, deny, or condition a permit, irrespective of whether

that person participated in the public comment process, may commence a contested case

in OAH to challenge any term of a permit or to challenge the issuance or denial of a

permit in toto, provided that petitioner can show that she is a person aggrieved. In the

Carolinas Cement case, for example, one of the petitioners had not participated in the

public comment process. Notwithstanding, neither OAH nor the NC APA placed limits

on that petitioners right to challenge any term of the permit by which it showed it was

aggrieved.

The EAB, in its sole discretion, may grant or deny a petition. In contrast, a North

Carolina Administrative Law Judge can dismiss a petition but must base the dismissal on

grounds provided in Rule 12 of the North Carolina Rules of Civil Procedure (similar to

Rule 12 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure). Petitioners whose petition has been

denied or dismissed may appeal to the courts, provided they can make the required

showing of standing.

For jurisdictions where EPA is the permitting authority, the EAB includes a number of

procedural requirements, unrelated to Article III, that must be satisfied to obtain judicial review.

These include a statement of the reasons supporting the review, a demonstration that issues

raised were raised during the public comment period, and a showing that a challenged condition

is based on a finding of fact or conclusion of law that is clearly erroneous, an abuse of discretion,

or a policy consideration which the EAB should, in its discretion, review.3

North Carolina provides its citizens easier access to judicial review when compared to the

hurdles in the federal process a citizen must overcome to challenge an air or water permit. Your

procedures can even be more restrictive for obtaining judicial review under an Article III court.

EPAs position on review by EAB, in response to comments objecting to the substantial showing

required to justify an appeal, was that review should only be sparingly exercised.4 NCDEQ

finds your agencys restrictions on citizens access, specifically in cases that involve

environmental justice concerns, to be troublesome.5

See, Native Village of Kivalina IRA Council v. EPA, 687 F.3d 1216 (9th Cir., 2012), in which Kivalina was denied

access in Federal Court to review by the EAB because its petition for review did not argue or explain why the

EPAs responses [to its comments] were incorrect, did not sufficiently engage the EPAs responses to public

comments, did not demonstrate why the [EPAs] responses to comments were clearly erroneous or otherwise

warranted review, and did not adequately address the EPAs responses about the sufficiency of permit

requirements. These were judgments by EPA employees in an EPA forum that resulted in denial by the 9th Circuit

Court of Appeals of judicial review. Under the federal review process, these citizens, who would have clearly

satisfied Article III standing, were denied judicial review.

4

45 Fed. Reg. 33290, 33412 (May 18, 1980).

5

See Footnote 3.

Heather McTeer Toney

January 11, 2016

Page 6

Illustrations of North Carolina APA

Under the NC APA, persons aggrieved, subsequent to being granted judicial review, must

demonstrate that they will be substantially prejudiced by the agencys decision (e.g., the permit).

As will be illustrated below, this is a separate and distinct element of the judicial review. In the

Carolinas Cement case, it was the failure to satisfy the showing of substantial prejudice required

by the NC APA on which summary judgment was granted by the Administrative Law Judge. The

Carolinas Cement was actually three separate cases on each of three iterations of one air quality

permit. None of the cases were decided on the issue of standing. Access to judicial review is

measured by the standard applied for standing. The Administrative Law Judge explicitly found

that the Petitioners had standing as persons aggrieved.6 Thus, claims that North Carolina

inappropriately put restrictions on citizen access to appellate forums are false.

In the first case, filed in April 2012, the Administrative Law Judge dismissed four of the eighteen

claims based on failure to state a claim upon which relief could be granted and for lack of subject

matter jurisdiction. The petitioner withdrew another of its eighteen claims. Importantly, the

Administrative Law Judge granted the Petitioners motion for summary judgment on standing

holding that the Petitioner had alleged sufficient facts to demonstrate that they were persons

aggrieved with standing to challenge the permit.7 However, the Administrative Law Judge

found that the Petitioner, despite more than a year of discovery, had failed to prove that element

of its case.8,9 The citizen groups were afforded access to OAH and, subsequently, to Superior

Court because they had made the requisite showing for standing under the APA; thus, they were

entitled to develop and produce evidence to meet their burden but, in cross-motions for summary

judgment, came up short.

N.C. Coastal Fedn v. N.C. Dept of Envt & Natural Res., 12 EHR 02850 at p.2 (NCOAH, Sept. 23, 2013). It

should be noted that the ALJ in these cases, Judge Beecher Gray, was also the author of the seminal decision in

Empire Power, upheld by North Carolinas Supreme Court, that recognized third party appeals in OAH (in addition

to appeal rights already recognized in Superior court). In other words, this ALJs decision in Empire Power greatly

broadened citizen access to the citizen-access process that your agency had already found sufficient prior to that

decision.

7

Petitioners Motion for Partial Summary Judgment is GRANTED IN PART to the extent the MOTION sought a

determination as to whether Petitioners are persons aggrieved with standing to commence this contested case. See,

N.C. Gen. Stat. 150B-23(a); Empire Power Co. v. Dept of Envt Health & Natural Res., 337 N.C. 569, 588, 447

S.E.2d 768, 779 (1994).

8

Id.

9

In contrast to the judicial review provided in this case and the massive discovery, depositions, expert reports,

briefings, written decisions at the Office of Administrative Hearings, the North Carolina Environmental

Management Commission, and the NC Superior Court (currently on appeal at the North Carolina Court of Appeals),

the EPA concluded that Californias judicial review procedures were acceptable despite the fact that for power

plants, judicial review is dependent solely on the discretion of the California Supreme Court. Moreover, the EPA

specifically found that even a petition from a citizen seeking judicial review that is denied by the California

Supreme Court, at its discretion, without even so much as a written opinion, satisfied the EPAs judicial review

requirement. 77 Fed. Reg. 65305 (October 26, 2012) (EPA approval of San Joaquin Valley Unified Air Pollution

Control Districts PSD program response to comments).

6

Heather McTeer Toney

January 11, 2016

Page 7

The issue of Article III is not relevant because the NC APA already provides judicial review

using a less restrictive person aggrieved standing requirement. ([w]hether or not Petitioners

could satisfy Article III standing is irrelevant to this case since petitioners had their day in court.

They were not denied judicial review. They were not denied standing. They simply did not prove

an essential element of their case, substantial prejudice.10) The position advanced by the North

Carolina Attorney General throughout the proceeding was consistent with the 1993 Attorney

Generals opinion. For example, it was argued whether Petitioners have demonstrated Article

III standing is irrelevant since they were not denied judicial review. [The department] never

contested whether petitioners had standing under Empire Power.11

In the second case, following a modification to the permit, petitioners filed again, making the

same claims but did not challenge the modified terms. The result in the second case was,

predictably, a repeat of that of the first case. Following another permit modification, petitioners

filed yet again, alleging essentially the same claims. The third case was also resolved on crossmotions for summary judgment, with the added rationale that petitioners were collaterally

estopped from raising the same issues yet a third time.

Petitioners appealed the decisions from OAH to the North Carolina Superior Court. Petitioners

had access to the reviewing court by virtue of their demonstration of standing as a person

aggrieved. The decision was upheld on judicial review after a full and fair opportunity to brief

and argue the cases. In upholding the Administrative Law Judge, the Superior Court stated that

[p]etitioners had ample time and opportunity to conduct discovery in an effort to establish the

elements of their claims. In fact, the discovery period . . . was over a year. N.C. Coastal Fedn v.

N.C. Dept of Envt & Natural Res., 13 CVS 015906, 14 CVS 007436, 14 CVS 009199 at p.7 (Sup.

Ct., Mar. 25, 2015). The Petitioners demonstrated that they were person[s] aggrieved entitling

them to judicial review and were provided ample opportunity to prove their case at the

administrative level and at the Superior Court level.

In the Martin Marietta case, the Administrative Law Judge granted a third party intervenors

motion for summary judgment on the basis that the citizen-petitioners had failed to show that

they were persons aggrieved, and, alternatively, on the substantive issues. It is critical to note

that this department took no position as to whether Petitioners had made the showing that they

were persons aggrieved. The respondent-intervenors advanced the argument that the citizenpetitioners were not person[s] aggrieved under the NC APA. As you are aware, on appeal, the

Superior Court examined the issue of person aggrieved (i.e., standing under the NC APA)

and found that the citizen-petitioners had standing and remanded the matter for a full plenary

hearing in OAH. It is unclear to NCDEQ in what conceivable way this would be a case that

limit[ed] citizen access to judicial review of environmental permits in North Carolina. To the

contrary, it is an example of the breadth of citizen access to such review.

Brief of Respondent at 30, N.C. Coastal Fedn v. N.C. Dept of Envt & Natural Res., 13 CVS 015906, 14 CVS

007436, 14 CVS 009199 (Wake County Sup. Ct., Sept. 19, 2014).

11

Brief of Respondent, supra note 10, at 30.

10

Heather McTeer Toney

January 11, 2016

Page 8

Conclusion

It is not clear to me whether your concern is based on misrepresentations of the facts of these

cases, an unfamiliarity with the facts, a misinterpretation of the law and rules, or some other

basis. The threshold for citizen access to OAH or to the state appellate courts has not changed

since the early 1990s, when citizen access was dramatically expanded. Although you state in

the second paragraph of your letter that an explanation was forthcoming as to how the decisions

cast serious doubt on whether North Carolinas NPDES and CAA/PSD programs satisfy federal

requirements for access to judicial review, that explanation has never materialized. Instead, the

letter simply concludes that undue restriction on citizen access may have occurred and that

affirming decisions by North Carolina courts would jeopardize North Carolinas authorization to

implement the NPDES and CAA/PSD programs.

Read as a general statement of the need to provide citizen access to judicial review of permits,

this letter could have gone to any state program in the country. In the context of the two

particular cases to which your letter refers, your concern appears to rest on an assertion with a

highly questionable foundation. In the Carolina Cement case, standing, or lack of citizen access

to judicial review, was not the issue on which the petitioners lost; in the Martin Marietta case, the

court reversed the OAH dismissal based on lack of standing (as one of two alternative bases, the

second of which was substantive).

Your expression of concern under these circumstances suggests that the federal government

believes that any third party challenge to a permit must be allowed to proceed, irrespective of its

merits, unlike your own position vis--vis review in the EAB. Advancing such a belief is a

disservice to both the regulated community as well as meritorious claims of third parties who

seek administrative and judicial review of environmental permits. As evidenced by the

discussion above, the department has demonstrated a continuous commitment to ensure persons

aggrieved by permit decisions have their claims heard.

We trust that this discussion above will satisfy your concerns regarding third party appeals in

North Carolina and provide you with an opportunity to review and revise your federal procedures

to ensure that they, like North Carolinas process, provide appropriate access to judicial review.

If questions remain, please contact my General Counsel, Sam Hayes, at 919-707-8616 to discuss

possible changes you would seek to the statutory language that the Courts have interpreted in the

two cases described above. We look forward to discussing this matter with you at your

convenience to get a better understanding of your purpose in sending it.

Sincerely,

Donald R. van der Vaart

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

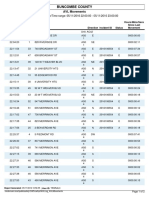

- 2015 Complete CalendarDokument359 Seiten2015 Complete CalendarJon OstendorffNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Fire Service Fact Sheet 2016Dokument7 SeitenFire Service Fact Sheet 2016Jon OstendorffNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- GPS Log For Police Patrol CarDokument2 SeitenGPS Log For Police Patrol CarJon OstendorffNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Trish Smothers Personnel RecordsDokument3 SeitenTrish Smothers Personnel RecordsJon OstendorffNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- WLOS News 13 Public Records Request - Western ResidenceDokument5 SeitenWLOS News 13 Public Records Request - Western ResidenceJon OstendorffNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Federal Education Funding in NC, 2014-15Dokument43 SeitenFederal Education Funding in NC, 2014-15Jon OstendorffNoch keine Bewertungen

- News 13 Water TestsDokument9 SeitenNews 13 Water TestsJon OstendorffNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- FW Summary of March 17 Closed SessionDokument4 SeitenFW Summary of March 17 Closed SessionJon OstendorffNoch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- FW Summary of March 17 Closed SessionDokument4 SeitenFW Summary of March 17 Closed SessionJon OstendorffNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Ben Teague Nov. 20 EmailDokument1 SeiteBen Teague Nov. 20 EmailJon OstendorffNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- March 17 Closed DRAFT 2Dokument1 SeiteMarch 17 Closed DRAFT 2Jon OstendorffNoch keine Bewertungen

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- FW Confidential Project BravoDokument2 SeitenFW Confidential Project BravoJon OstendorffNoch keine Bewertungen

- March 17 Closed DRAFT 2Dokument1 SeiteMarch 17 Closed DRAFT 2Jon OstendorffNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Motion For DefaultDokument5 SeitenMotion For DefaultJon OstendorffNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Buncombe Expenses 2013-14Dokument1 SeiteBuncombe Expenses 2013-14Jon OstendorffNoch keine Bewertungen

- Asheville City Fee Increase PlanDokument11 SeitenAsheville City Fee Increase PlanJon OstendorffNoch keine Bewertungen

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Email Exchange Between Commissioner Debruhl and EDC Director TeagueDokument2 SeitenEmail Exchange Between Commissioner Debruhl and EDC Director TeagueJon OstendorffNoch keine Bewertungen

- November Email To Wanda Greene From Ben TeagueDokument1 SeiteNovember Email To Wanda Greene From Ben TeagueJon OstendorffNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Redacted Comments Attributed To Buncombe Commission Chairman GanttDokument2 SeitenRedacted Comments Attributed To Buncombe Commission Chairman GanttJon OstendorffNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Transfer of The Bent Creek, or Ferry Road, PropertyDokument8 SeitenTransfer of The Bent Creek, or Ferry Road, PropertyJon OstendorffNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Buncombe Expenses 201415Dokument1 SeiteBuncombe Expenses 201415Jon OstendorffNoch keine Bewertungen

- Original Horsehead PermitDokument6 SeitenOriginal Horsehead PermitJon OstendorffNoch keine Bewertungen

- Buncombe Expenses 201415Dokument1 SeiteBuncombe Expenses 201415Jon OstendorffNoch keine Bewertungen

- Buncombe Expenses 2013-14Dokument1 SeiteBuncombe Expenses 2013-14Jon OstendorffNoch keine Bewertungen

- Original Horsehead PermitDokument6 SeitenOriginal Horsehead PermitJon OstendorffNoch keine Bewertungen

- Horsehead Corp Violations ListDokument2 SeitenHorsehead Corp Violations ListJon OstendorffNoch keine Bewertungen

- Colville GenealogyDokument7 SeitenColville GenealogyJeff MartinNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (120)

- Returns To Scale in Beer and Wine: A P P L I C A T I O N 6 - 4Dokument1 SeiteReturns To Scale in Beer and Wine: A P P L I C A T I O N 6 - 4PaulaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ronaldo FilmDokument2 SeitenRonaldo Filmapi-317647938Noch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine CuisineDokument1 SeitePhilippine CuisineEvanFerrerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Creative Writing PieceDokument3 SeitenCreative Writing Pieceapi-608098440Noch keine Bewertungen

- Homicide Act 1957 Section 1 - Abolition of "Constructive Malice"Dokument5 SeitenHomicide Act 1957 Section 1 - Abolition of "Constructive Malice"Fowzia KaraniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Data Warga RT 02 PDFDokument255 SeitenData Warga RT 02 PDFeddy suhaediNoch keine Bewertungen

- Different Types of Equity Investors - WikiFinancepediaDokument17 SeitenDifferent Types of Equity Investors - WikiFinancepediaFinanceInsuranceBlog.comNoch keine Bewertungen

- Online Advertising BLUE BOOK: The Guide To Ad Networks & ExchangesDokument28 SeitenOnline Advertising BLUE BOOK: The Guide To Ad Networks & ExchangesmThink100% (1)

- OD428150379753135100Dokument1 SeiteOD428150379753135100Sourav SantraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Working Capital FinancingDokument80 SeitenWorking Capital FinancingArjun John100% (1)

- Greek Gods & Goddesses (Gods & Goddesses of Mythology) PDFDokument132 SeitenGreek Gods & Goddesses (Gods & Goddesses of Mythology) PDFgie cadusaleNoch keine Bewertungen

- JONES - Blues People - Negro Music in White AmericaDokument46 SeitenJONES - Blues People - Negro Music in White AmericaNatalia ZambaglioniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Critique On The Lens of Kantian Ethics, Economic Justice and Economic Inequality With Regards To Corruption: How The Rich Get Richer and Poor Get PoorerDokument15 SeitenCritique On The Lens of Kantian Ethics, Economic Justice and Economic Inequality With Regards To Corruption: How The Rich Get Richer and Poor Get PoorerJewel Patricia MoaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Ais CH5Dokument30 SeitenAis CH5MosabAbuKhater100% (1)

- WAS 101 EditedDokument132 SeitenWAS 101 EditedJateni joteNoch keine Bewertungen

- LSG Statement of Support For Pride Week 2013Dokument2 SeitenLSG Statement of Support For Pride Week 2013Jelorie GallegoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wendy in Kubricks The ShiningDokument5 SeitenWendy in Kubricks The Shiningapi-270111486Noch keine Bewertungen

- Napoleon BonaparteDokument1 SeiteNapoleon Bonaparteyukihara_mutsukiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Study For Southwestern University Food Service RevenueDokument4 SeitenCase Study For Southwestern University Food Service RevenuekngsniperNoch keine Bewertungen

- Financial Management: Usaid Bin Arshad BBA 182023Dokument10 SeitenFinancial Management: Usaid Bin Arshad BBA 182023Usaid SiddiqueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comparative AnalysisDokument5 SeitenComparative AnalysisKevs De EgurrolaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civics: Our Local GovernmentDokument24 SeitenCivics: Our Local GovernmentMahesh GavasaneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ta 9 2024 0138 FNL Cor01 - enDokument458 SeitenTa 9 2024 0138 FNL Cor01 - enLeslie GordilloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Test Bank For Global 4 4th Edition Mike PengDokument9 SeitenTest Bank For Global 4 4th Edition Mike PengPierre Wetzel100% (32)

- Snyder, Timothy. The Reconstruction of Nations. Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569-1999 (2003)Dokument384 SeitenSnyder, Timothy. The Reconstruction of Nations. Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569-1999 (2003)Ivan Grishin100% (8)

- Buyer - Source To Contracts - English - 25 Apr - v4Dokument361 SeitenBuyer - Source To Contracts - English - 25 Apr - v4ardiannikko0Noch keine Bewertungen

- Certified Data Centre Professional CDCPDokument1 SeiteCertified Data Centre Professional CDCPxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bangladesh Labor Law HandoutDokument18 SeitenBangladesh Labor Law HandoutMd. Mainul Ahsan SwaadNoch keine Bewertungen

- BB Winning Turbulence Lessons Gaining Groud TimesDokument4 SeitenBB Winning Turbulence Lessons Gaining Groud TimesGustavo MicheliniNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Russia Hoax: The Illicit Scheme to Clear Hillary Clinton and Frame Donald TrumpVon EverandThe Russia Hoax: The Illicit Scheme to Clear Hillary Clinton and Frame Donald TrumpBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (11)

- Modern Warriors: Real Stories from Real HeroesVon EverandModern Warriors: Real Stories from Real HeroesBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (3)

- Crimes and Cover-ups in American Politics: 1776-1963Von EverandCrimes and Cover-ups in American Politics: 1776-1963Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (26)

- The Courage to Be Free: Florida's Blueprint for America's RevivalVon EverandThe Courage to Be Free: Florida's Blueprint for America's RevivalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stonewalled: My Fight for Truth Against the Forces of Obstruction, Intimidation, and Harassment in Obama's WashingtonVon EverandStonewalled: My Fight for Truth Against the Forces of Obstruction, Intimidation, and Harassment in Obama's WashingtonBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (21)

- Game Change: Obama and the Clintons, McCain and Palin, and the Race of a LifetimeVon EverandGame Change: Obama and the Clintons, McCain and Palin, and the Race of a LifetimeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (572)