Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

UDK v. KU Lawsuit Filing (04-08-16)

Hochgeladen von

Lawrence Journal-WorldOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

UDK v. KU Lawsuit Filing (04-08-16)

Hochgeladen von

Lawrence Journal-WorldCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Case 2:16-cv-02085-CM-GLR Document 5 Filed 04/08/16 Page 1 of 32

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF KANSAS

VICKY DIAZ-CAMACHO, individually and in

her capacity as Editor in Chief of the University

Daily Kansan;

KATIE KUTSKO, individually and in her

capacity as prior Editor in Chief of the

University Daily Kansan; and

THE UNIVERSITY DAILY KANSAN,

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

Plaintiffs,

)

)

vs.

)

)

BERNADETTE GRAY-LITTLE, in her capacity )

as the University of Kansas Chancellor and in )

her individual capacity; and

)

TAMMARA DURHAM, in her capacity as the )

University of Kansas Vice Provost for Student )

Affairs and in her individual capacity,

)

)

Defendants.

)

Case No. 16-cv-2085-CM

MEMORANDUM AND BRIEF IN OPPOSITION

TO DEFENDANTS MOTION TO DISMISS

COME NOW Plaintiffs, by and through counsel, and for their Memorandum and Brief in

Opposition to Defendants Motion to Dismiss (Doc. 4), state the following:

1. Statement of the Matter Before the Court

The defendants, administrators at a state university, consciously and voluntarily slashed

government-fee funding to the universitys student newspaper to punish the newspaper and its

editorial staff for their criticism of campus activities. As stated in the Complaint, the desire and

intent to chill the plaintiffs exercise of constitutional press freedoms were confirmed by

numerous sources. The defendants did not disavow this attack on First Amendment rights, and

Case 2:16-cv-02085-CM-GLR Document 5 Filed 04/08/16 Page 2 of 32

instead cut funding to the student newspaper in half, incorporating the reduced funding into the

Fee Schedule for the official school budget for 2015-2016.

As a result, the newspaper cut back on staffing and the student editors struggled with how

to cover campus news, knowing that further retaliation could result. And as stated in the

Complaint, the threat of additional retaliation was in fact reported to a news editor. After the

Complaint was filed, this reduced funding was provisionally extended for an additional term in

the state universitys 2016-2017 budget; the student editors sought relief from the defendants, but

defendants have refused to even acknowledge this request. Unless defendants act or are forced to

act, this content-based reduced funding will continue into the foreseeable future.

Plaintiffs are the proper parties to bring this action and to seek redress for these

constitutional violations. The defendants funding cut to the student newspaper was based on its

content, violates the First Amendment and does not withstand the scrutiny required for such

retaliation.

The required fact-intensive analysis of the defendants decision making role in punishing

the exercise of constitutional press rights on campus confirms that defendants are state actors

who were fully aware of and actively involved in the decision to retaliate against plaintiffs.

Whether this Court views the students involved in initial budget discussions as state actors,

private citizens or (as defendants have theorized) members of a state legislature, the defendants

conduct which is the focus of these claims establishes liability for the constitutional violation that

is continuing in nature, both in the current budget cycle and in upcoming funding.

This Court should allow plaintiffs claims to proceed.

2

Case 2:16-cv-02085-CM-GLR Document 5 Filed 04/08/16 Page 3 of 32

2. Statement of the Facts

While this Court should review and accept all facts presented by plaintiffs as true for

purposes of this motion, plaintiffs believe the following facts are of particular significance for a

ruling on defendants motion.

The first named plaintiffs are Vicky Diaz-Camacho and Katie Kutsko. Complaint, Doc. 1,

3. These two plaintiffs work at the Kansan, and during critical times in the history and this

litigation they have held the position of Editor-in-Chief of the Kansan. Doc. 1, 3; Ex. 1 and Ex.

2 (Declarations of Vickey Diaz-Camacho and of Katie Kutsko). The Editor has responsibility for

the editorial content of the Kansan. Doc. 4-1 (UDK Constitution). Katie Kutsko was Editor-inChief at the time the critical editorial was first published, and again during the first semester

(Fall 2015) when the Kansan had to deal with the financial damage of the cut in funding

triggered by the Kansans publication of that editorial. Ex. 2. Katie Kutsko continues to work on

the Kansan news staff during the current (Spring 2016) semester, once again under the reduced

funding level. Id. Vicky Diaz-Camacho is the current Editor-in-Chief for the Kansan. Ex. 1. She

bears responsibility for the Kansans content. Doc. 4-1. During both the Fall 2015 and the

current Spring 2016 semesters, the Kansan had operated without an editorial adviser because of

the reduction in the Kansans funding. Exs. 1, 2. This reduced funding has caused the Kansan to

cut the number of reporters and to trim the hours that the remaining reporters work. Exs. 1, 2.

The third plaintiff is the University Daily Kansan, an unincorporated association

governed by a Constitution that was approved by Chancellor Gray-Littles predecessor. Doc. 1

3, Doc. 4-1.

3

Case 2:16-cv-02085-CM-GLR Document 5 Filed 04/08/16 Page 4 of 32

Besides its advertising, the major source of the Kansans funding is from the mandatory

student activity fee. Doc. 1 8. Defendant Gray-Little establishes the fee amounts as part of the

Universitys official budget, sometimes upon recommendation from the student senate

organization. Doc. 1, 4, 24. But Gray-Little also has unilaterally imposed fees for matters of

significance to the University, such as KU athletics. Doc. 1, 39. The Kansans funding from the

student activity fee had been set at $2.00 per student before the 2015-2016 budget. Doc. 1, 15.

The Kansan transitioned to a digital first format, consistent with the trend for national

and general news organizations. Doc, 1, 9. This reduced the number of hard copies of the

Kansan published on a weekly basis, with a commensurate decline in advertising revenue. Lower

publishing costs did not match this decline in revenue, leaving the Kansan more dependent on

funding from the student activity fee. Id.

The Kansan learned of numerous criticisms of its content made during the fee review

process but before a proposed activity fee amount was forwarded to the Chancellor. Doc. 1,

13-22; Ex. 3, Declaration of Jon Schlitt. These criticisms came from student leaders whose

actions and procedures were the focus of the editorial; the Kansan categorized the procedures as

confusing and called out inadequacies in the election process. Doc. 1, 10-12. Among

other facts, this documented evidence consisted of the following, all of which was stated as part

of or contemporaneous with the fee review process:

The student vice president said I would be worried if I was the UDK;

The student president complained, Why do they always make me sound like a

dumbass?;

4

Case 2:16-cv-02085-CM-GLR Document 5 Filed 04/08/16 Page 5 of 32

The student president was disappointed in the Kansans coverage, the lack of

quality reporting, and was angry over Professor Johnsons editorial;

The student president wanted to punish the Kansan for the editorial and

encouraged the fee review committee to punish the Kansan with a reduction in

funds until editorial content had been fixed;

The former student vice president said some of the coverage had been really

problematic, articles were not vetted before publication, that the editorial content

was a main factor in decreasing the Kansans funding, and that the fee reduction

would be reviewed the following year after these problems had been addressed.

Doc. 1, 13-20; Ex. 3.

The recommendation to the Chancellor was to cut the Kansans funding from the student

activity fee in half. Doc. 1, 21-22, Ex. 3.

The Kansan provided these facts and a letter from the Student Press Law Center to the

Chancellor before she finalized the 2015-2016 budget. Doc. 1, 23-24; Ex. 3. Gray-Little

authorized defendant Durham to handle this matter. Doc. 1, 24; Ex. 3. The Kansan provided

this same evidence to Durham, but Durham did not review this before meeting with the Kansan,

expressing surprise at the critical comments made about the Kansan as part of the budget

consideration process. Doc. 1, 25-26; Ex. 3. The student president was also present, and did

not deny criticizing the Kansan and encouraging a reduction in the Kansans fee to fix its

content. Doc. 1, 26; Ex. 3. The Kansans Chairman of the Board warned told both defendants

that reducing the Kansans fee because of its content would violate the First Amendment. Ex. 3.

Case 2:16-cv-02085-CM-GLR Document 5 Filed 04/08/16 Page 6 of 32

The defendants took no further action to respond to this constitutional violation. Doc. 1,

28-31; Ex. 3. Instead, the defendants slashed the Kansans funding in the Universitys 20152016 budget by fifty percent. Doc. 1, 31; Ex. 3. No other student organization experienced this

financial reduction in the budget. Doc. 1, 22.

As a direct result of the reduction in its funding, the Kansan has operated without an

editorial adviser. Doc. 1, 33; Exs. 1-3. This reduced funding has caused the Kansan to cut the

number of reporters and to trim the hours that the remaining reporters work. Id.

Roughly one month before the fee review process began for the 2016-2017 budget, a fee

review committee representative told the Kansans news editor that the Kansan staff got what

you deserved and that the Kansan had bit the hand that fed it. Doc. 1, 37; Ex. 3.

After plaintiffs filed this lawsuit, the recommendation to the Chancellor was to keep the

Kansans funding for the 2016-2017 budget at the reduced level. Ex. 1. Vicky Diaz-Camacho

wrote to Gray-Little, pleading with the Chancellor to stop this retaliation against the Kansan for

its content. Doc. 1, 38; Ex. 1. The Chancellor did not respond to this plea. Ex. 1.

The Universitys 2016-2017 budget will soon be finalized.

3. Questions Presented

When accepting as true all facts presented by plaintiffs, have defendants met their burden

of proof to challenge plaintiffs standing, the legal sufficiency of the claims presented, and the

Case 2:16-cv-02085-CM-GLR Document 5 Filed 04/08/16 Page 7 of 32

appropriateness of the relief sought, and have defendants met their burden of proof on the

applicability of Legislative Immunity to public university administrators and students.

Plaintiffs submit that the answers to all questions are in the negative.

4. Argument

This Response is organized by a review of the appropriate legal standards; a discussion of

the parties both the plaintiffs and the defendants; authority for the claims that are presented;

analysis of the Legislative Immunity asserted by defendants; a review of the causation defense

based on Legislative Immunity; and a brief discussion of the declaratory relief sought against

defendants in their official capacity. Finally, for completeness and out of an abundance of

caution plaintiffs seek and reserve the right to amend any portion of the Complaint as directed by

the Court.

A. Legal Standards for Ruling on a Motion to Dismiss

The Court and defendants should accept all well-pleaded allegations as true and construe

all reasonable inferences from those facts in favor of the plaintiffs. Witt v. Roadway Express,

136 F.3d 1424, 1428 (10th Cir. 1998). [W]e must determine whether the complaint sufficiently

alleges facts supporting all the elements necessary to establish an entitlement to relief under the

legal theory proposed. Forest Guardians v. Forsgren, 478 F.3d 1149, 1160 (10th Cir. 2007).

Although a plaintiff must provide more than labels and conclusions, [or] a formulaic recitation

of the elements of a cause of action, Bell Atl. Corp. v. Twombly, 550 U.S. 544 (2007),

Case 2:16-cv-02085-CM-GLR Document 5 Filed 04/08/16 Page 8 of 32

[s]pecific facts are not necessary; the statement need only give the defendant fair notice of what

the . . . claim is and the grounds upon which it rests. Erickson v. Padrus, 551 U.S. 89 (2007).

Only when it appears beyond a doubt that a plaintiff can prove no set of facts that

would allow relief should dismissal be ordered. Maher v. Durango Metals, Inc., 144 F.3d 1302,

1304 (10th Cir.1998). The issue is whether a plaintiff is entitled to offer evidence to support the

claims. Scheuer v. Rhoades, 416 U.S. 232, 236 (1974), overruled on other grounds, Davis v.

Scherer, 468 U.S. 183 (1984).

(The Parties)

B. The Appropriate Parties are Before This Court - Plaintiffs Have Standing to

Bring These Claims and Defendants are the Proper Parties for the Relief Sought

Herein (Parts IV, V, VI and VII of defendants motion)

In their motion Defendants take the position that none of the plaintiffs are the proper

parties to bring the constitutional claims asserted here. Defendants phrase this as a standing

issue. In ruling on such a motion, the Court and defendants must assume that the allegations of

the complaint are true and construe the allegations in favor of plaintiffs. Cressman v. Thompson,

719 F.3d 1139, 1144 (10th Cir. 2013).

Plaintiffs Vicky Diaz-Camacho and Katie Kutsko have brought this lawsuit both

individually and in their representative capacity as, respectively, current and former editors-inchief of the Kansan. The Kansan also sues. Plaintiffs allege that they engaged in conduct

protected under the First Amendment, that the defendants took action against them and chilled

the plaintiffs protected press freedoms, and that plaintiffs protected conduct was a substantial

or motivating factor for the defendants action. All plaintiffs seek injunctive relief, a declaratory

judgment, and nominal damages. See p. 15 of the Complaint (Doc. 1).

8

Case 2:16-cv-02085-CM-GLR Document 5 Filed 04/08/16 Page 9 of 32

The fundamental requirements of standing are an injury in fact caused by the conduct

complained of that will likely be redressed by a favorable decision in the case. Lujan v.

Defenders of Wildlife, 504 U.S. 555, 560-61 (1992). At bottom, the gist of the question of

standing is whether [plaintiffs] have such a personal stake in the outcome of the controversy as to

assure that concrete adverseness which sharpens the presentation of issues upon which the court

so largely depends for illumination. Massachusetts v. E.P.A., 549 U.S. 497, 517 (2007)

(quotations omitted).

Because of the significance of First Amendment rights, the Supreme Court has

enunciated other concerns that justify a lessening of prudential limitations on standing. Phelps

v. Hamilton, 122 F.3d 1309, 1326 (10th Cir.1997)(quoting Sec'y of State of Md. v. Joseph H.

Munson Co., 467 U.S. 947, 956 (1984).

This is, of course, a case where an actual controversy exists. See Surefoot LC v. Sure

Foot Corp., 531 F.3d 1236, 1240 (10th Cir. 2008). Plaintiffs are not seeking an advisory opinion.

Defendants took away the Kansans funding in retaliation for the Kansans content, and

plaintiffs seek to stop this injury and have the funding restored.

I. Injury in Fact to These Plaintiffs

As alleged in the Complaint, the plaintiffs gather and report news as the student voice for

the University of Kansas. Defendants have provided a copy of the Kansans Constitution Doc. 41; as stated therein, the Kansans editor bears full responsibility for its editorial content.

Case 2:16-cv-02085-CM-GLR Document 5 Filed 04/08/16 Page 10 of 32

Displeasure arose at the University of Kansas because the Kansan criticized campus

elections, categorizing the process as confusing and pointing out inadequacies in election

procedures. Plaintiff Katie Kutsko was editor-in-chief when the Kansan published these

criticisms.

The Kansan is funded through its advertising and student activity fees. The defendants

herein, the Vice Provost of Student Affairs, and the Chancellor of the University, review student

recommendations on the student activity fee portion of the universitys budget, including the

Kansans portion of this fee. The University collects and distributes these mandatory fees.

In the next budget after this editorial was published, defendants cut funding to the

Kansan in half. This reduced funding established an injury in fact, since withdrawing financial

support to a student newspaper constitutes censorship of constitutionally protected expression.

Joyner v. Whiting, 477 F.2d 456, 460 (4th Cir. 1973).

The Doyle decision cited by defendants, Doyle v. Oklahoma Bar Assn, 998 F.2d 1559

(10th Cir. 1993), does not support dismissal of these plaintiffs. Doyle sought to interject himself

into a state bar disciplinary proceeding, but this was insufficient to establish jurisdiction, or

injury to this litigant. [T]he only one who stands to suffer direct injury in a disciplinary

proceeding is the lawyer involved. Doyle has no more standing to insert himself substantively

into a license-based discipline system than he has to compel the issuance of a license. Doyle,

998 F.2d at 1567. And unlike the unsuccessful appellant in Robbins v. Oklahoma, 519 F.3d 1242

(10th Cir. 2008), plaintiffs allegations here have made it clear who did what to whom:

10

Case 2:16-cv-02085-CM-GLR Document 5 Filed 04/08/16 Page 11 of 32

defendants cut state funding to the Kansan in half because of dissatisfaction with the Kansans

content.

There is no dispute that First Amendment rights extend to the campuses of state

universities. Widmar v. Vincent, 454 U.S. 263, 268-69 (1981). The content of a student

publication cannot be a basis for funding decisions. Rosenberger v. Rector Visitors of Univ. of

Virginia, 515 U.S. 819 (1995). A public university may not constitutionally withhold funding

from a student newspaper because it disapproves of the content of the paper. Stanley v. Magrath,

719 F.2d 279, 282 (8th Cir. 1983).

Plaintiff Vicky Diaz-Camacho is the current editor-in-chief, while plaintiff Katie Kutsko

held that position in fall 20151; in this capacity both suffered from the reduced operating funds

due to defendants cut to the Kansans funding for the 2015-16 budget cycle. The defendants cut

in the funding required defendants to eliminate and not fill editorial positions at the Kansan and

to reduce hours for remaining editorial staff.

In the First Amendment context, injury occurs when a plaintiff is chilled from exercising

those constitutional rights. See, e.g., Ward v. Utah, 321 F.3d 1263, 1267, 1269 (10th Cir. 2003).

A chilling effect arises from the deterrent effect of governmental action, even if this falls short of

a direct prohibition against the exercise of First Amendment rights. Laird v. Tatum, 408 U.S. 1,

Former student editors are proper plaintiffs to bring such claims. See, e.g., Stanley v.

Magrath, 719 F.2d 279 (8th Cir. 1983); see also Case v. Unified School Dist. No. 233, 895

F.Supp. 1463 (D.Kan. 1995) (former students could pursue injunctive and declaratory relief for

school officials removal of controversial book from school libraries).

11

Case 2:16-cv-02085-CM-GLR Document 5 Filed 04/08/16 Page 12 of 32

11 (1972). The very essence of a chilling effect is an act of deterrence. Freedman v. Maryland,

380 U.S. 51, 59 (1965).

When a state university official takes retaliatory action against a newspaper its content,

the official's action creates a chilling effect which gives rise to a First Amendment injury.

See

Stanley v. Magrath, 719 F.2d at 283. The Declarations of plaintiffs Diaz-Camacho and Kutsko

confirm that this chilling effect. The loss of First Amendment freedoms, for even minimal

periods of time, unquestionably constitutes irreparable injury. Elrod v. Burns, 427 U.S. 347,

373-74 (1976).

This case involves a direct, monetary injury in retaliation for the exercise of First

Amendment rights. The retaliatory reduction in funding deterred plaintiffs from gathering and

reporting on the news, and constituted an unconstitutional chilling effect on the exercise of those

rights.

II. The injury is fairly traceable to the defendants conduct

As alleged in the Complaint, defendants cut funding to the Kansan in half, from $2 to $1.

This reduced funding is identified as a line-item in the Universitys official budget setting forth

mandatory student activity fees. Ex. 4, University of Kansas Comprehensive Fee Schedule,

FY2016, at pg. 6. Defendants are the state actors who made this budget decision.

Defendants claim that it was not their conduct that injured plaintiffs; instead, defendants

are in effect blaming KU students for this unconstitutional retaliation against the Kansan and its

editors. Plaintiffs have described the involvement of these students in the Complaint. While

12

Case 2:16-cv-02085-CM-GLR Document 5 Filed 04/08/16 Page 13 of 32

conduct of other people may have contributed to a harm, that does not alter the conclusion that

defendants are liable for their actions. See Northington v. Marin, 102 F.3d 1564, 1569 (10th Cir.

1996).

None of their blame-shifting diminishes the defendants role. There is no budget without

the defendants approval. There is no financial punishment against the Kansan without the

defendants conduct. This was more than just tacit approval in, or rubber stamping of, a sheet of

paper that comes across a state administrators desk; this case involves the Universitys official

budget. Plaintiffs met with each of the defendants and pointed out to them the unconstitutional

retaliation in reducing funding because of the Kansans content, and these statements have not

been denied. This violation of plaintiffs First Amendment rights was foreseeable, and

preventable. In recent years the university administration has unilaterally increased the

mandatory student activity fee to fund KU athletics. Defendants had the opportunity to do the

same here to avoid a constitutional violation.

The cut in the Kansans funding is an injury that is directly traceable to the defendants.

III. A Favorable Decision on the Merits Will Redress the Injury

As relief for this constitutional violation, plaintiffs seek injunctive and declaratory relief,

including nominal damages. Complaint, Doc. 1, p. 15. Such relief is appropriate for the

defendants actions. Section 1983 independently provides a right to obtain injunctive relief. See

Wilder v. Virginia Hospital Assn, 496 U.S. 498, 501 (1990). Plaintiffs specifically seek an

injunction prohibiting Defendants, their successors, and assigns, and all persons acting in concert

therewith from enforcing the retaliatory budget allocation and reducing the Kansans student

13

Case 2:16-cv-02085-CM-GLR Document 5 Filed 04/08/16 Page 14 of 32

activity fee allocation from its 2014-2015 level; and prohibiting them from enforcing further

retaliatory allocations in the 2016-2017 budget.

Such relief addresses the injury that plaintiffs have suffered by focusing on the funding

that was slashed in retaliation for the Kansans content. Injunctive relief has long been

recognized as the proper means for preventing entities from acting unconstitutionally. Federal

Deposit Insurance Corporation v. Meyer, 510 U.S. 471, 474 (1994).

The real and imminent likelihood of future injury supports plaintiffs claims for

prospective injunctive relief. See City of Los Angeles v. Lyons, 461 U.S. 95, 111 (1983). As

shown by the plaintiffs Declarations, the Kansan and its editorial staff have been injured and

will continue to suffer because the defendants cut the Kansans funding.

Moreover, plaintiffs are threatened because without intervention this retaliation will be

repeated in the 2016-2017 budget and the chilling effect on the Kansans newsroom will

continue. Since this lawsuit was filed, this threat has moved closer to reality. The Kansan stands

to suffer further retaliation because the proposed upcoming budget keeps the Kansans funding

at only one-half of the previous amount. Plaintiffs have requested that defendants intervene as

the Chancellor had done on student activity funding to KU athletics but defendants failed to

even acknowledge this plea. These are continuing, adverse effects that can only be corrected

through judicial intervention.

Similarly, declaratory relief is appropriate for First Amendment violations. The text of

1983 provides that defendants shall be liable to the party injured in an action at law, suit in

equity, or other proper proceeding for redress. This language has been construed to include

14

Case 2:16-cv-02085-CM-GLR Document 5 Filed 04/08/16 Page 15 of 32

declaratory relief. Carey v. Piphus, 435 U.S. 247 (1978) (action for declaratory judgment,

injunctive relief, and damages). A claim for declaratory judgment is generally prospective, but

declaratory relief is treated as retrospective to the extent that it is intertwined with a claim for

monetary damages that requires us to declare whether a past constitutional violation occurred.

PETA v. Rasmussen, 298 F.3d 1198, 1202 n.2 (10th Cir. 2002)

Plaintiffs actual injury entitles them to damages under Section 1983 for violation of their

constitutional rights. See Dill v. City of Edmond, 155 F.3d 1193, 1209 (10th Cir. 1998).

Significantly, in Carey v. Piphus the Court authorized the recovery of nominal damages not only

to perform a declaratory function, but also to vindicate legal rights. 435 U.S. at 266-67. The

Tenth Circuit has followed and expanded upon this approach. In Committee for the First

Amendment v. Campbell, the Tenth Circuit did not dismiss the claim for nominal damages as

moot even when the claim for injunctive relief was dismissed. The court took a benevolent

approach to nominal damage awards and found that this sole basis of relief conferred standing:

We reverse due to legal error...., the district court erred in dismissing the nominal

damages claim ... . If proven, a violation of First Amendment rights concerning freedom

of expression entitles a plaintiff to at least nominal damages.

Committee for the First Amendment, supra, 962 F.2d 1517, 1526-27 (10th Cir. 1992).

Plaintiffs have shown that they meet all the elements for standing to pursue the relief

sought in their Complaint.

15

Case 2:16-cv-02085-CM-GLR Document 5 Filed 04/08/16 Page 16 of 32

IV. The Kansan Has Standing to Bring Constitutional Claims

in Federal Court

Defendants motion includes the contention that under the state law of Kansas, the

Kansan cannot bring this lawsuit as a plaintiff. Defendants may be correct on this point, and are

correct that the Kansan is unincorporated, but neither of these facts is dispositive for the standing

issue. Defendants did not address Rule 17(b)(3) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, which

provides

Rule 17. Plaintiff and Defendant; Capacity; Public Officers

(b) Capacity to Sue or Be Sued. Capacity to sue or be sued is determined as follows:

(1)

or an individual who is not acting in a representative capacity, by the law of the

individual's domicile;

(2)

for a corporation, by the law under which it was organized; and

(3)

or all other parties, by the law of the state where the court is located, except that:

(A) a partnership or other unincorporated association with no such

capacity under that state's law may sue or be sued in its common name to enforce

a substantive right existing under the United States Constitution or laws;

Plaintiff Kansan is entitled, even as an unincorporated association situated in Kansas, to

bring this action in federal court to enforce First Amendment rights; congressional intent for this

conclusion is evident from adoption of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. And the Kansans

Constitution makes clear that this unincorporated organization is governed by a Board of

Directors and runs as a business. Defendants motion also does not address Lippoldt v. Cole, 468

F.3d 1204 (10th Cir. 2006). In that decision F.R.C.P. Rule 17(b)(3) was not raised by the parties

or discussed by the Court. That decision did not address the congressional intent that is evident

from enactment of Rule 17(b)(3), and where the congressional intent is clear, it governs.

Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corp. v. Bonjorno, 494 U. S. 827, 837 (1990).

16

Case 2:16-cv-02085-CM-GLR Document 5 Filed 04/08/16 Page 17 of 32

V. Defendants are Proper Parties for the Relief Sought

(Part III -V of defendants motion)

A significant aspect of the defense strategy seems to be an effort to distance themselves

from the public universitys budget process. The facts show otherwise. The plaintiffs proof will

demonstrate an affirmative link between the constitutional deprivation and defendants personal

participation and exercise of control or direction. See Meade v. Grubbs, 841 F.2d 1512, 1527

(10th Cir. 1988). The fact that the constitutional violation began at the student level does not

absolve defendants from their responsibility for and control over the public universitys budget.

In the past few years, the KU administration has exercised authority and control over the student

activity fee, adjusting amounts as they deemed necessary or appropriate. See 39 of the

Complaint (defendant Gray-Little unilaterally increases student activity fee to fund KU

athletics).

Defendants were put on notice of the constitutional violation arising from the cut in the

Kansans funding based on its content. Both defendants participated in the decision to do

nothing. When governmental policymakers are put on notice of constitutional violations and do

nothing, such a policy of inaction is deemed to be the functional equivalent of a decision by

the [governmental entity] itself to violate the Constitution. City of Canton v. Harris, 489 U.S.

378, 395 (1989).

The proper defendants in a 1983 claim are those who represent [the state] in some

capacity, whether they act in accordance with their authority or misuse it. Nat'l Collegiate

Athletic Ass'n v. Tarkanian, 488 U.S. 179, 191 (1988) (quoting Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S.

17

Case 2:16-cv-02085-CM-GLR Document 5 Filed 04/08/16 Page 18 of 32

167, 172 (1961). The Tenth Circuit has found 1983 liability based upon a decision made by a

final policymaker; see, e.g., Flanagan v. Munger, 890 F.2d 1557, 1568-69 (10th Cir.

1989)(finding 1983 liability where decisions of police chief for all intents and purposes were

final decision).

Contrary to the Kansas Constitution, defendants identify themselves and dozens of KU

students as members of the Kansas legislature, and thereby entitled to legislative immunity. The

actions of both the KU Student Senate and the defendants in this case are legislative in nature.

Doc. 4 at p. 17. Such a self-serving proclamation would be a surprise to the state representatives

in Topeka who have actually been voted into office, and such a claim would deserve more

discussion if defendants had provided the Court with even one case holding that public university

administrators and students are in fact state legislators. This case certainly would be the first to

so hold.

Article 2 of the Kansas Constitution establishes and describes the states legislative body;

defendants do not fall within this definition. While the Tenth Circuit interprets legislative

immunity broadly, Sable v. Myers, 563 F.3d 1120, 1125 (10th Cir. 2009), this is quite different

from interpreting broadly who is in the legislature, as defendants would have this Court do.

As shown by the Supreme Court decision in Rosenberger v. Rector Visitors of Univ. of

Virginia, 515 U.S. 819 (1995), by the Fourth Circuits holding in Joyner v. Whiting, 477 F.2d

456 (4th Cir. 1973) and the Eighth Circuits decision in Stanley v. Magrath, 719 F.2d 279 (8th

Cir.1983), funding of student publications is not a legislative process, and the withholding of

state funds to these news outlets based on content violates the First Amendment. None of those

18

Case 2:16-cv-02085-CM-GLR Document 5 Filed 04/08/16 Page 19 of 32

parties and neither of the defendants here are somehow legislators, legislative immunity does not

apply.

Defendants are the decision makers for the state universitys budget, including the

recommendations on funding that are received from student leaders. They are proper defendants

for this 1983 claim. Defendant Gray-Little was the final decision maker on the universitys

budget, and had unilaterally imposed mandatory fees on KU students to fund the universitys

athletic program. Defendant Gray-Little directed defendant Durham to investigate the

constitutional violations against the Kansan, and Durham handled the meeting with the Kansan

and student leaders, who did not deny having said that the Kansans funding needed to be cut

until its content improved. Both Gray-Little and Durham decided to do nothing, and by not

acting violated the Constitution. City of Canton v. Harris, 489 U.S. 378, 395 (1989).

(The Claims)

C. Plaintiffs Are Authorized to Bring Count I Claims (Part I of defendants Motion)

The concept of a direct claim under the federal Constitution is neither novel nor new. The

Supreme Court explained its understanding of jurisdiction over such claims in this manner: the

district court has jurisdiction if the right of the petitioners to recover under their complaint will

be sustained if the Constitution and laws of the United States are given one construction and will

be defeated if they are given another, unless the claim clearly appears to be immaterial and

made solely for the purpose of obtaining jurisdiction or where such a claim is wholly

insubstantial and frivolous. Steel Co. v. Citizens for Better Environment, 523 U. S. 83, 89

(1998)(citations omitted).

19

Case 2:16-cv-02085-CM-GLR Document 5 Filed 04/08/16 Page 20 of 32

Relying on 28 U.S.C. 1331 as a basis for jurisdiction, the telecommunications company

Verizon filed an action in the U.S. District Court for the District of Maryland against the Public

Service Commission of Maryland, its individual members in their official capacities, and others.

Verizon Md. Inc. v. Public Serv. Commn of Md, 535 U.S. 635 (2002). In its complaint, Verizon

sought declaratory and injunctive relief on the basis that the state commissions order was

unconstitutional. Writing for the Supreme Court, Justice Scalia found no indication that

Verizons claim was immaterial or wholly insubstantial and frivolous. 535 U.S. at 643.

Verizons constitutional challenge thus fell within 28 U.S.C. 1331s general grant of

jurisdiction and was upheld by the Supreme Court.

For the claims in Count I of their Complaint, plaintiffs seek similar relief to what Verizon

pursued against the Maryland state commission. See plaintiffs Prayer for Relief. Plaintiffs

claims in Count I and the relief sought is consistent with the Supreme Courts holding in the

Verizon decision.

For litigation arising under the First Amendment, the Supreme Court has assumed,

without so holding, the viability of Bivens-type claims. The Court made this assumption in

Hartman v. Moore, where a Bivens plaintiff claimed that government employees violated his

First Amendment rights by participating in retaliatory litigation against him. Hartman v. Moore,

547 U.S. 250 (2006). More recently, the Court reiterated this belief in Ashcroft v. Iqbal, stating

that it was assum[ing], without deciding, that [a] First Amendment claim is actionable under

Bivens. Ashcroft v. Iqbal, 556 U.S. 662, 129 S. Ct. 1937, 1948 (2009).

20

Case 2:16-cv-02085-CM-GLR Document 5 Filed 04/08/16 Page 21 of 32

Another district court in this Circuit addressed Tenth Circuit precedent in considering a

direct claim brought under the First Amendment against state actors. After a thorough analysis of

the decision in Planned Parenthood of Kansas & Mid-Missouri v. Moser, 747 F.3d 814 (10th

Cir. 2014), the District Court for the District of New Mexico held

Because SWEPI, LP can bring its claims under the First, Fifth, and Fourteenth

Amendments through 1983, Planned Parenthood of Kansas and Mid-Missouri v.

Moser not only does not prevent SWEPI, LP from bringing a claim under the

Supremacy Clause for those violations, it suggests that SWEPI, LP can bring such a

claim.

Swepi, LP v. Mora County, No. CIV 14-0035 JB/SCY, Slip. Op. at p. 9 (D.N.M. Jan.

19, 2015).

This area of constitutional law has been developing during the twenty-first century. Rather

than viewing the propriety of 1983 as a basis for precluding such claims, the current trend is to

recognize such claims as further support for direct claims under the Constitution, at least for the

type of relief plaintiffs seek in this lawsuit. cf. Verizon Md. Inc., supra, 535 U.S. 635. Plaintiffs

claims in Count I fit squarely within this authority and should go forward.

D. Plaintiffs Are Authorized to Bring Count I Claims (Part II of defendants motion)

Defendants challenge to Count II of the Complaint relies solely on the Kansas Tort

Claims Act, K.S.A. 75-6101 et seq. (Kansas Tort Claims Act Does Not Create a Right of Action

for Constitutional Torts). Plaintiffs do not bring their claim against defendants based on the

state Tort Claims Act. See Doc. 1 - Count II. Instead, this is a direct claim based on violations of

21

Case 2:16-cv-02085-CM-GLR Document 5 Filed 04/08/16 Page 22 of 32

the Kansas Constitution and seeking injunctive and declaratory relief. Assertion of this claim is

consistent with a body of Kansas caselaw.

In Brick Co. v. Perry, 69 Kan. 297, 76 Pac. 848 (1904), the Kansas Supreme Court struck

down a Kansas statute which made it unlawful to prevent employees from joining or belonging

to a labor union. Before granting relief, the Supreme Court noted that the petition alleged that the

statute violated both the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution and section 1

of the Kansas Constitution Bill of Rights. 69 Kan. at 298-99.

Violations of the Kansas Constitution as the basis for a claim for relief are also found in

the criminal law field, such as a double jeopardy challenge based on section 10 of the Kansas

Constitution Bill of Rights. State v. Schoonover, 281 Kan. 453, 475, 133 P.3d 48 (2006).

[I]mposing sentences for both convictions violated Applebys rights to be free from double

jeopardy as guaranteed by the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution and 10 of the

Kansas Constitution Bill of Rights. State v. Appleby, 289 Kan. 1017, 221 P.3d 525 (2009).

Recently, a number of Kansas school districts contended that the funding method for

public education adopted by the Kansas legislature was a violation of Article 6 of the Kansas

Constitution. The Kansas Supreme Court found that these direct claims under the Kansas

Constitution presented a justiciable case or controversy. Gannon v. State, 298 Kan. 1107, Syl.

4, 319 P.3d 1196 (2014).

Less than three months ago, the Kansas Court of Appeals considered the appeal of an

abortion rights ruling, and concluded that

22

Case 2:16-cv-02085-CM-GLR Document 5 Filed 04/08/16 Page 23 of 32

[S]ections 1 and 2 of the Kansas Constitution Bill of Rights provide the same protection

for abortion rights as the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

United States Constitution; the district court correctly determined that the Kansas

Constitution Bill of Rights provides a right to abortion.

Hodes & Nauser MDs, P.A., et al. v. Schmidt, No. 114,153, Slip op. at p. ___ (January

22, 2016).

Count II of plaintiffs Complaint asserts a claim directly under the Kansas Constitution.

Section 11 of the Kansas Constitution Bill of Rights states: The liberty of the press shall be

inviolate; and all persons may freely speak, write or publish their sentiments on all subjects,

being responsible for the abuse of such rights . . . .. According to the Kansas Supreme Court,

Section 11 of the Kansas Bill of Rights is generally considered coextensive with the First

Amendment of the federal Constitution. State v. Russell, 227 Kan. 897, 899, 610 P.2d 1122

(1980), cert. denied, 449 U.S. 983, 101 S. Ct. 400, 66 L. Ed. 2d 245 (1985). Challenges to state

statutes under Section 11 of the Kansas Bill of Rights have been considered in State v. Stauffer

Communications, Inc., 592 P. 2d 891, 225 Kan. 540 (1979) and Stephens v. Van Arsdale, 608

P. 2d 97, 227 Kan. 676 (1980).

The state courts of Kansas have entertained lawsuits brought under Article 6 of the

Kansas Constitution and, inter alia, Sections 1, 2, 10 and 11 of the Kansas Bill of Rights.

Consistent with this line of authority, the Kansas Tort Claims Act does not preclude plaintiffs

from bringing this claim in Count II of the Complaint.

E. The Unconstitutional Conditions Doctrine Does Not Preclude Plaintiffs Claims

(Part III of defendants motion)

23

Case 2:16-cv-02085-CM-GLR Document 5 Filed 04/08/16 Page 24 of 32

It is well-settled law that First Amendment protections extend to public universities. The

Supreme Court has described the university as a traditional sphere of free expression that is

fundamental to the functioning of our society, and as a result governmental control over free

expression on campus is carefully scrutinized. Keyishian v. Board of Regents, 385 U.S. 589,

603, 605-606 (1967)(free speech case).

Funding that student newspapers receive from universities is a too-frequent source of

First Amendment violations when state administrators react adversely to content. A public

university's establishment of a student media outlet typically involves the creation of a limited

public forum, which means that the ability of school administrators to interfere with the speech

made through such an outlet is strictly curtailed. Censorship of constitutionally protected

expression cannot be imposed by withdrawing financial support, or asserting any other form

of censorial oversight. Joyner v. Whiting, 477 F.2d 456, 460 (4th Cir. 1973).

The Eighth Circuit adopted a similar protection of college newspapers funding in

Stanley v. Magrath, 719 F.2d 279 (8th Cir.1983).

After the University of Minnesotas student

newspaper published a humor issue, the Universitys Board of Regents changed the method by

which it funded the newspaper. Student publications in the past had been funded by a mandatory

student fee, but the Board decided to let students obtain a refund of this fee if they so desired.

Former editors of the Daily, the Daily itself, and the Board of Student Publication brought suit.

They claimed that the Regents instituted the refundable fee system in response to the content of

the controversial issue and, as a result, violated the First Amendment. The Eighth Circuit agreed,

explaining that [a] public university may not constitutionally take adverse action against a

24

Case 2:16-cv-02085-CM-GLR Document 5 Filed 04/08/16 Page 25 of 32

student newspaper, such as withdrawing or reducing the paper's funding, because it disapproves

of the content of the paper. Id. at 282

When the University of Virginia used mandatory student fees to pay for student

publications but then excluded religious speech from this program, the restriction was

impermissible content-based discrimination.

Rosenberger v. Rector Visitors of Univ. of

Virginia, 515 U.S. 819, 833 (1995). In explaining its decision, the Supreme Court stated that

prohibiting expressions based on content was contrary to longstanding [v]ital First Amendment

speech principles, including the need to protect against the danger of chilling student

speech. Id. at 836. The Supreme Court determined that denial of funding equated to denial of

access based on content. Id. at 835-37. See also Board of Regents v. Southworth, 529 U.S. 217,

223, 229 (2000)(mandatory student fee passed constitutional muster only if the university

provided protection in the form of the requirement of viewpoint neutrality in the allocation of

funding support).

The reason why such retaliation offends the Constitution is that it threatens to inhibit

exercise of the protected right. Pickering v. Board of Education, 391 U.S. 563, 574 (1968).

Retaliation can thus be akin to an unconstitutional condition demanded for the receipt of a

government-provided, albeit unrelated, benefit. See Perry v. Sindermann, 408 U.S. 593, 597

(1972). For retaliation cases, the inquiry will necessarily examine the officials motive for

taking the action. Bd. of Cnty. Commrs v. Umbehr, 518 U.S. 668, 675 (1996).

Under the unconstitutional conditions doctrine, the government may not require a

person to give up a constitutional right in exchange for a discretionary benefit conferred by the

25

Case 2:16-cv-02085-CM-GLR Document 5 Filed 04/08/16 Page 26 of 32

government where the benefit sought has little or no relationship to the property. See Perry v.

Sindermann, supra (teaching position conditioned upon not criticizing college administration).

The Tenth Circuit has said that the focus of the unconstitutional conditions doctrine is

on whether a governmental entity is denying a benefit to [a plaintiff] that [the plaintiff] could

obtain by giving up [his or her] freedom of speech, or is penalizing [the plaintiff] for refusing to

give up [his or her] First Amendment rights. KT G Corp. v. Att'y Gen. of Okla., 535 F.3d 1114,

1136 (10th Cir. 2008). But the matter before this Court is very different from the Moser case

cited by defendants, both factually and substantively. In Planned Parenthood of Kansas and

Mid-Missouri v. Moser, the plaintiff did not bring a private action under 1983 for a Title X

violation, and Title X did not create a private right of action. See Planned Parenthood of Kan. &

Mid-Missouri v. Moser, 747 F.3d at 823-28. By contrast, it has been long recognized that a

private citizen can bring an action under the First Amendment. See Zwickler v. Koota, 389 U.S.

241 (1967)(addressing private action for First Amendment violation). In Count III here, the

plaintiffs have brought a private action under 1983 for the violation of their First Amendment

rights. Plaintiffs allege that defendants retaliated through reduced funding because of the

Kansans content.

While the Moser litigants challenged legislation that had the effect of

disqualifying them from government funding, here plaintiffs do not allege any action by the

Kansas Legislature (which was the focus in Moser) which violated their rights; it was the

defendants, as administrators at this public university, who retaliated for the Kansans content by

cutting its funding.

One of the most recent higher court discussions of this doctrine was three years ago,

when the Supreme Court held that a governmental policy violated the First Amendment because

26

Case 2:16-cv-02085-CM-GLR Document 5 Filed 04/08/16 Page 27 of 32

it conditioned receipt of federal funding on an organization affirming a belief that by its nature

cannot be confined within the scope of the Government program. The Court made it clear that

[w]ere it enacted as a direct regulation of speech, the Policy Requirement would plainly violate

the First Amendment. United States Agency for International Development v. Alliance for

Open Society International, Inc., 570 U.S. ___, Slip op. at 15. (2013).

Such authority is consistent with the view that the unconstitutional conditions doctrine

prohibits the government from requiring a person to give up a constitutional right in exchange

for a discretionary benefit conferred by the government where the benefit sought has little or no

relationship to the property. See Perry v. Sindermann, 408 U. S. 593 (1972).

Here the situation is different - there is a direct connection between the government

funding that defendants withheld and the plaintiffs exercise of First Amendment press freedoms.

There is a pure and direct relationship between the two, unlike the typical unconstitutional

conditions cases. But plaintiffs claims do not fail simply because they do not fit nicely into the

framework of most unconstitutional conditions doctrine cases; this doctrine is not the full scope

of the sum total of First Amendment protections. Defendants argument sets up a straw man just

to knock it down.

Defendants profess ignorance of motivation to retaliate against the Kansan based on its

content, but if defendants did not know it was only because they were indifferent to the

constitutional violation and its effect. Plaintiffs provided defendant Gray-Little with

documentation showing that the Kansans content was the reason for cutting the Kansans

funding. Professor Johnson told her that clear violations of the First Amendment had occurred

27

Case 2:16-cv-02085-CM-GLR Document 5 Filed 04/08/16 Page 28 of 32

which required her intervention. When Gray-Little assigned the matter to defendant Durham for

handling, Durham did not even review any of the documentation on the retaliation that had been

hand-delivered to her. Durham expressed surprise when told of a student leaders statement that

the Kansans funding needed to be cut until its content improved. The student leader was present

at this meeting and did not deny saying that the Kansans funding needed to be cut until its

content improved. Professor Johnson told Durham that injecting the Kansans content into the

Fee Review process had infected all funding discussions from top to bottom and in the process

violated the First Amendment. Yet defendants did nothing but demonstrate indifference and

antipathy towards the First Amendment violation. When governmental policymakers are put on

notice of constitutional violations and yet do nothing, their inaction is the functional equivalent

of a decision by the governmental entity itself to violate the Constitution. City of Canton v.

Harris, 489 U.S. 378, 395 (1989).

F. Plaintiffs have Established Causation Against Defendants (Parts III, IV and V of

defendants motion)

Defendants repeat throughout their Motion the causation argument that is based on a

faulty premise (see Doc. 4, pp. 12-15, 15-16 and 17-18). This repetition does not make their

argument any more viable. Defendants claim that they were uninformed and disinterested

bystanders in whatever dispute had arisen on the university campus, and that they had no control

over the student activity fee in the Universitys budget, deferring to the Student Senate.

Plaintiffs have already provided to the Court in this Response the salient facts: that the cut to the

Kansans budget was improperly motivated by the Kansans content; that the defendants were

brought into this dispute to prevent the constitutional violation and were provided evidence of

28

Case 2:16-cv-02085-CM-GLR Document 5 Filed 04/08/16 Page 29 of 32

this wrongful motivation, which was not disputed by student leaders; that defendants did nothing

to address this constitutional violation; and that defendants had ultimate control over the budget,

including the student activity fee, as shown by defendant Gray-Littles unilateral increase in the

fee to fund KU athletics.

Since legislative immunity does not extend to university administrators or students, and

since the universitys cuts to funding of a student publication based on its content violates the

First Amendment, the defendants causation argument fails both on the facts and the law.

Defendants case of Worrell v. Henry, 219 F.3d 197 (10th Cir. 2000) supports a finding in

plaintiffs favor: as noted by the Worrell court, a plaintiff must show that a connection exists

between the constitutional deprivation and either the defendants personal participation, exercise

of control or direction, or failure to supervise. 219 F.3d at 1214, citing Meade v. Grubbs, 841

F.2d 1512, 1527 (10th Cir. 1988). This is what plaintiffs have alleged: the retaliation against the

plaintiffs took place because the defendants reviewed, adopted, applied and enforced the

unconstitutional cuts based on the Kansans content.

(The Relief)

G. The Declaratory Relief Sought by Plaintiffs is Appropriate (Part VIII of

defendants motion)

Defendants last point is limited to an argument regarding the defendants in their official

capacity. The Eleventh Amendment does not bar a federal court from ordering notice or

declaratory relief in a suit against the state if it is ancillary to a judgment awarding prospective

injunctive relief. See Johns v. Stewart, 57 F.3d 1544, 1553 (10th Cir.1995). The Johns court

was citing defendants own case, Green v. Mansour, 474 U.S. 64, 70-74, 371 (1985), in making

this ruling.

29

Case 2:16-cv-02085-CM-GLR Document 5 Filed 04/08/16 Page 30 of 32

The Declaratory Judgment Act of 1934, 28 U.S.C. 2201, permits a federal court to

declare the rights of a party whether or not further relief is or could be sought, and we have held

that under this Act declaratory relief may be available even though an injunction is not. Steffel v.

Thompson, 415 U.S. 452, 462 (1974). Moreover, plaintiffs allege a continuing violation, not just

a past violation of their constitutional rights. Compare Green v. Mansour, supra.

Defendants do not raise any argument regarding the appropriateness of this relief agains

the defendants in their individual capacity.

H. Plaintiffs Seek Amendment on Any Points, If Necessary

Out of an abundance of caution, plaintiffs seek and reserve their right to amend any part

of their Complaint if the Court so directs. Defendants have not answered the Complaint and

plaintiffs have not had the opportunity to pursue discovery. A district court should not dismiss

claims with prejudice for failure to state a claim unless it appears beyond doubt that the plaintiff

can prove no set of facts in support of his claim which would entitle him to relief. Hall v.

Bellmon, 935 F.2d 1106, 1109 (10th Cir. 1991), quoting Conley v. Gibson, 355 U.S. 41, 45-46,

(1957); [I]f it is at all possible that the party against whom the dismissal is directed can correct

the defect in the pleading or state a claim for relief, the court should dismiss with leave to

amend. 6 C. Wright & A. Miller, Federal Practice & Procedure, 1483, at 587 (2nd ed. 1990).

See also Tate v. Farmland Industries, Inc., 268 F.3d 989, 997 (10th Cir. 2001)(imposing a

patently obvious standard for futility of amendment before allowing dismissals without

opportunity for amendment).

30

Case 2:16-cv-02085-CM-GLR Document 5 Filed 04/08/16 Page 31 of 32

CONCLUSION

As they must, defendants assume all of these allegations as true for purposes of their

motion. As shown herein, a clear constitutional violation occurred. So if plaintiffs the student

editors and the publication are not the parties to seek relief for the constitutional violations,

defendants must provide the answer of who is entitled. Their motion is silent on this point.

The defendants had full knowledge of the constitutional violation and they had it in their

power to prevent the injury to plaintiffs. Even after the factual allegations were not denied in a

face-to-face meeting, defendants still chose to adopt and authorize the retaliatory cut to the

plaintiffs funding.

This Court should exercise its jurisdiction to provide plaintiffs with the relief sought

herein.

WHEREFORE, plaintiffs pray for denial of defendants motion and for such other and

further relief as sought herein and as this Court deems just and equitable.

DORAN LAW OFFICE

By: /s/ Patrick J. Doran

Patrick J. Doran

#13150

4324 Belleview, Suite 200

Kansas City, MO 64111

(816) 753-8700

Fax (816) 753-4324

pjdoran@doranlaw.net

ATTORNEY FOR PLAINTIFFS

31

Case 2:16-cv-02085-CM-GLR Document 5 Filed 04/08/16 Page 32 of 32

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that I electronically filed the above and foregoing document with the

clerk of the court by using the CM/ECF system which will send a notice of electronic filing to

the following counsel of record, on April 8, 2016:

Michael C. Leitch

University of Kansas Associate General Counsel and

Special Assistant Attorney General

245 Strong Hall

1450 Jayhawk Blvd.

Lawrence, Kansas 66045

mleitch@ku.edu

/s/ Patrick J. Doran

Patrick J. Doran

32

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Fight CPS HandbookDokument60 SeitenFight CPS Handbookfree100% (3)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Strunk and Phelps - Amicus Curiae Brief and Appendix USCA 9th Circuit 15-15343Dokument169 SeitenStrunk and Phelps - Amicus Curiae Brief and Appendix USCA 9th Circuit 15-15343Christopher Earl Strunk100% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Lawsuit Against Chicago Aviation DepartmentDokument27 SeitenLawsuit Against Chicago Aviation DepartmentjroneillNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Complaint - Conner v. Alltin LLC, Et AlDokument19 SeitenComplaint - Conner v. Alltin LLC, Et AlChina Lee100% (1)

- Memorandum in Opposition To Temporary Restraining OrderDokument22 SeitenMemorandum in Opposition To Temporary Restraining OrderinforumdocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Spencer Lawsuit ComplaintDokument15 SeitenSpencer Lawsuit ComplaintLas Vegas Review-JournalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Appellants Brief and Appendix Forjone V California 10-822 112910Dokument465 SeitenAppellants Brief and Appendix Forjone V California 10-822 112910Christopher Earl Strunk100% (2)

- D READ This Understanding The Executor OfficeDokument27 SeitenD READ This Understanding The Executor OfficeDean Golden100% (3)

- Terraform V SECDokument12 SeitenTerraform V SECfleckalecka100% (1)

- Douglas County Advance Voting Schedule - 2016 General ElectionDokument1 SeiteDouglas County Advance Voting Schedule - 2016 General ElectionLawrence Journal-WorldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Drafted 2017-2021 Capital Improvement Plan For The Lawrence Police DepartmentDokument9 SeitenDrafted 2017-2021 Capital Improvement Plan For The Lawrence Police DepartmentLawrence Journal-WorldNoch keine Bewertungen

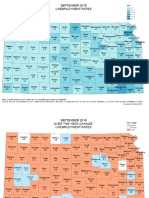

- Kansas Unemployment by County (Sept. 2016)Dokument2 SeitenKansas Unemployment by County (Sept. 2016)Lawrence Journal-WorldNoch keine Bewertungen

- KDOT Final Report On K-10/Kasold IntersectionDokument26 SeitenKDOT Final Report On K-10/Kasold IntersectionLawrence Journal-WorldNoch keine Bewertungen

- East Ninth Design Development Document (April 2016)Dokument81 SeitenEast Ninth Design Development Document (April 2016)Lawrence Journal-WorldNoch keine Bewertungen

- USD497 School District 2015-16 MapDokument1 SeiteUSD497 School District 2015-16 MapLawrence Journal-WorldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lawrence Police Facility Needs Assessment and Pre-Design StudyDokument61 SeitenLawrence Police Facility Needs Assessment and Pre-Design StudyLawrence Journal-WorldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Master Plan: Clinton Farms DevelopmentDokument1 SeiteMaster Plan: Clinton Farms DevelopmentLawrence Journal-WorldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oread Design Guidelines (March 21, 2016)Dokument198 SeitenOread Design Guidelines (March 21, 2016)Lawrence Journal-WorldNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2016 Kindergarten Roundup ScheduleDokument2 Seiten2016 Kindergarten Roundup ScheduleLawrence Journal-WorldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Report: Building Code and Inspection Function For Douglas County, KansasDokument128 SeitenReport: Building Code and Inspection Function For Douglas County, KansasLawrence Journal-WorldNoch keine Bewertungen

- East Ninth CAC Presentation (3-2-16)Dokument9 SeitenEast Ninth CAC Presentation (3-2-16)Lawrence Journal-WorldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lawrence Transit System - Route 7Dokument1 SeiteLawrence Transit System - Route 7Lawrence Journal-WorldNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2016 Construction Proposals For Bob Billings ParkwayDokument6 Seiten2016 Construction Proposals For Bob Billings ParkwayLawrence Journal-WorldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lawrence Daily Journal-World (08-06-1945)Dokument2 SeitenLawrence Daily Journal-World (08-06-1945)Lawrence Journal-WorldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lawrence Citizen Survey 2015Dokument104 SeitenLawrence Citizen Survey 2015Lawrence Journal-WorldNoch keine Bewertungen

- K-10 West Leg: Preferred Access Alternative (North)Dokument1 SeiteK-10 West Leg: Preferred Access Alternative (North)Lawrence Journal-WorldNoch keine Bewertungen

- K-10 West Leg: Preferred Access Alternative (South)Dokument1 SeiteK-10 West Leg: Preferred Access Alternative (South)Lawrence Journal-WorldNoch keine Bewertungen

- City of Lawrence Performance Audit: Financial IndicatorsDokument34 SeitenCity of Lawrence Performance Audit: Financial IndicatorsLawrence Journal-WorldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lawrence Police Facility Study Session 7-20-2015Dokument40 SeitenLawrence Police Facility Study Session 7-20-2015Lawrence Journal-WorldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bain v. CTADokument23 SeitenBain v. CTAemma brownNoch keine Bewertungen

- JA Complaint FiledDokument54 SeitenJA Complaint FiledMichael KingNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Law and Racial Discrimination in EmploymentDokument73 SeitenThe Law and Racial Discrimination in EmploymentChristopher StewartNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pejovic Et Al V State University of New York at Albany Et LDokument64 SeitenPejovic Et Al V State University of New York at Albany Et LTimothy BurkeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Michael Storms Et Al Civil LawsuitDokument30 SeitenMichael Storms Et Al Civil LawsuitWXYZ-TV Channel 7 DetroitNoch keine Bewertungen

- CFTOD Motion To DismissDokument55 SeitenCFTOD Motion To DismissChristie ZizoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ward v. Shoupe, Et AlDokument29 SeitenWard v. Shoupe, Et AlAnonymous GF8PPILW5Noch keine Bewertungen

- Dillon McGee LawsuitDokument32 SeitenDillon McGee LawsuitThe Jackson SunNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Right To Live in The World: The Disabled in The Law of TortsDokument80 SeitenThe Right To Live in The World: The Disabled in The Law of TortsMichel André BreauNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bromley v. McCaughn, 280 U.S. 124 (1929)Dokument7 SeitenBromley v. McCaughn, 280 U.S. 124 (1929)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wonderland MallDokument87 SeitenWonderland MallKen HaddadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Roth v. United States, 354 U.S. 476 (1957)Dokument29 SeitenRoth v. United States, 354 U.S. 476 (1957)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Phyllis Faircloth, Administratix of the Estate of Jiles T. Lynch v. Herman Finesod, and Jackie Fine Arts, Inc. F. Peter Rose L.A. Walker C.S. Pulkinen National Settlement Associates of South Carolina, Inc. Marilyn Goldberg Marigold Enterprises, Ltd. Sigmund Rothschild, 938 F.2d 513, 4th Cir. (1991)Dokument9 SeitenPhyllis Faircloth, Administratix of the Estate of Jiles T. Lynch v. Herman Finesod, and Jackie Fine Arts, Inc. F. Peter Rose L.A. Walker C.S. Pulkinen National Settlement Associates of South Carolina, Inc. Marilyn Goldberg Marigold Enterprises, Ltd. Sigmund Rothschild, 938 F.2d 513, 4th Cir. (1991)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- II-B-III-4 US Vs Ling Su FanDokument9 SeitenII-B-III-4 US Vs Ling Su FandarylNoch keine Bewertungen

- William Christman Class Action Lawsuit Against Kalamazoo County TreasurerDokument16 SeitenWilliam Christman Class Action Lawsuit Against Kalamazoo County TreasurerWWMTNoch keine Bewertungen

- Econ 1 FinalsDokument3 SeitenEcon 1 FinalsEarl Russell S PaulicanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cornell Notes 6Dokument5 SeitenCornell Notes 6api-525394194Noch keine Bewertungen

- Thompson Preliminary InjunctionDokument41 SeitenThompson Preliminary InjunctionCincinnatiEnquirerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fitzgerald v. Barnstable School Committee, 555 U.S. 246 (2009)Dokument67 SeitenFitzgerald v. Barnstable School Committee, 555 U.S. 246 (2009)Legal MomentumNoch keine Bewertungen

- Smart V Corizon Amended ComplaintDokument23 SeitenSmart V Corizon Amended ComplaintAllegheny JOB WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Federal Lawsuit Against NYC by Airbnb UserDokument21 SeitenFederal Lawsuit Against NYC by Airbnb UserChristopher RobbinsNoch keine Bewertungen