Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

The Clinical Spectrum of Acute Glomerulonephritis and Lung Haemorrhage (Goodpasture's Syndrome)

Hochgeladen von

Sa 'ng WijayaOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The Clinical Spectrum of Acute Glomerulonephritis and Lung Haemorrhage (Goodpasture's Syndrome)

Hochgeladen von

Sa 'ng WijayaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Quarterly Journal of Medicine, New Series 55, No. 216, pp.

75-86, April 1985

The Clinical Spectrum of Acute Glomerulonephritis

and Lung Haemorrhage (Goodpasture's

Syndrome)

S. HOLDSWORTH, N. BOYCE, N. M. THOMSON and R. C. ATKINS

From the Departments of Nephrology and Medicine, Prince Henry's Hospital,

Melbourne, Australia

Accepted 27 November 1984

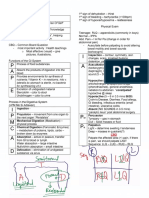

The aetiology, clinical features and outcome of 40 patients presenting with Goodpasture's

syndrome (glomerulonephritis with haemoptysis and pulmonary infiltrates) are reviewed. The

diseases of the patients studied could be divided into three groups: antiglomerular basement

membrane (anti-GBM) antibody-induced disease (7/40); systemic vasculitis (22/40) and idiopathic Goodpasture's syndrome (i.e. no systemic disease or anti-GBM antibody detected)

(11/40). Overall mortality was 57.5 per cent (anti-GBM disease 4/7; systemic vasculitis 15/22;

and idiopathic Goodpasture's syndrome 4/11). Most patients died of disease progression or

infection. End-stage renal failure developed in 26 patients (anti-GBM (7), vasculitis (14) and

idiopathic Goodpasture's syndrome (5). End-stage renal failure developed in 23 of 24 patients

presenting with a creatinine of > 600 (M/l regardless of the aetiology of Goodpasture's syndrome or treatment used. Review of renal histology showed that all had proliferative nephritis,

with 80 per cent of patients having more than 30 per cent crescents. Thus Goodpasture's

syndrome was associated with a wide variety of underlying disease. It had a poor prognosis,

with the degree of renal impairment at presentation, the extent of crescent formation and the

nature of the underlying disease being the major determinants of outcome.

INTRODUCTION

Patients with acute nephritis and lung haemorrhage are commonly regarded as having Goodpasture's syndrome (1). This clinical presentation can be associated with a variety of diseases

with variable course, prognosis and response to treatment. Stanton and Tange in 1954 (2)

reviewed the autopsy findings of patients who died with pulmonary haemorrhage and nephritis.

They searched the literature and named this syndrome in recognition of the inital report by

Goodpasture et al. in 1919 (3). The landmark studies of Lerner et al. (4) showed that eluted

antibody from the kidneys of some patients with Goodpasture's syndrome could induce nephritis

in primates, thus demonstrating that anti-GBM antibodies were of pathogenetic significance.

Following the delineation of the immunopathogenesis of anti-GBM disease many clinicians felt

Address for correspondence: Dr S. Holdsworth, Monash University Department of Medicine, Prince

Henry's Hospital, St Kilda Road, Melbourne 3004, Australia.

Downloaded from qjmed.oxfordjournals.org by guest on February 12, 2011

SUMMARY

76

S. Holdsworth and others

that all patients with Goodpasture's clinical syndrome had anti-GBM disease. Indeed it has been

suggested that the use of the eponym 'Goodpasture's syndrome' be restricted to patients with

the triad of lung haemorrhage, glomerulonephritis and evidence of anti-GBM antibody formation (5). However recent reports have demonstrated that lung haemorrhage and glomerulonephritis can occur without detectable anti-GBM antibodies (618). To gain some perspective

of the disease states, clinical features, and ultimate outcome of patients presenting with

Goodpasture's syndrome, we reviewed all cases presenting to a university teaching hospital

with this condition over a nine-year period.

METHODS

PATIENTS

HISTOLOGY

Renal biopsies were performed in all patients at the time of their acute presentation. Needle

biopsy cores were divided into three portions, the tissues being studied by light, immunofluorescent and electron microscopy.

Crescent score was defined as a percentage of glomeruli with a cellular accumulation in

Bowman's space greater than two cells in depth and occupying at least 30 per cent of the circumference of the glomerulus. Crescent scores were made using the number of non-sclerosed

glomeruli as the denominator.

CLINICAL INVESTIGATIONS

These included microscopy of urinary sediment; 24 h urinary protein excretion and creatinine

clearance; full blood examination including ESR and platelet counts; serum C3 and C4; circulating

immune complexes by Clq binding and Raji cell assays; C-reactive protein; antinuclear

factor; circulating anti-GBM antibodies by radioimmunoassay (19) and serial chest radiographs.

TREATMENT

Treatment (Table 1) varied according to the nature of the disease producing Goodpasture's

syndrome. Patients with anti-GBM disease were treated with prednisolone and either cyclophosphamide or azathioprine. In addition three patients underwent plasmapheresis. Patients

with vasculitis were treated with prednisolone, 12 with added cyclophosphamide and two with

added azathioprine. Only five of the 11 patients with idiopathic Goodpasture's syndrome were

treated with prednisolone and two of these also received cyclophosphamide. Duration of treatment is shown in Table 1. Prednisolone was commenced at 2 mg/kg/day and tapered over three

months to lOmg/day. Cyclophosphamide and azathioprine were given at 2 mg/kg/day.

Downloaded from qjmed.oxfordjournals.org by guest on February 12, 2011

An analysis of all patients presenting to Prince Henry's Hospital, Melbourne, with pulmonary

haemorrhage and acute nephritis from 1974 to 1982 (inclusive) was made. Criteria for inclusion

were: renal biopsy with evidence of acute nephritis; evidence of renal impairment (serum

creatinine at least twice normal); radiological evidence of a pulmonary infiltrate with the

simultaneous presence of frank haemoptysis (either at presentation to hospital or within 24 h of

admission).

Acute Glomerulonephritis and Lung Haemorrhage (Goodpasture's Syndrome)

11

TABLE 1. Therapeutic regimens*

Aetiology

No.

Immune suppression

Duration Other

of therapy therapy

(mean

used

months)

Cyclo and pred (5)

Aza and pred (2)

Pred alone (8)

Cyclo and pred (12)

Aza and pred (2)

3.4

12

32.6

16.4

65

Pred alone (3)

Cyclo and pred (2)

3.8

8

treated

Anti-GBM (7)

Vasculitis(22)

22

Idiopathic

Goodpasture's

syndrome (11)

Plasmapheresis (3)

Heparin (2)

Plasmapheresis (3)

Pulse steroids (4)

Plasmapheresis (1)

Heparin (1)

Pulse steroids (1)

RESULTS

Aetiology

Analysis of the underlying diseases present led to the designation of three aetiological categories.

Seven patients had anti-GBM antibody associated disease on the basis of the detection of circulating anti-GBM antibodies and the demonstration by immunofluorescence of linear GBM

deposition of IgG. Twenty-two patients had a systemic vasculitis with clinical, histological,

radiological, serological and immunological features characteristic of each disease (20). Eighteen

of these patients had a primary systemic vasculitic illness. These consisted of Wegener's granulomatosis (5); polyarteritis nodosal (3); systemic lupus erythematosus (5) and microscopic

polyarteritis (5). Four patients had vasculitis secondary to another disease (subacute bacterial

endocarditis (2); and tumour-associated microangiopathy (2). The remaining 15 patients had

TABLE 2. Clinical features

Anti-GBM

Vasculitis

Idiopathic

Goodpasture's

syndrome

Age

(mean in years)

42.7

54.9

35.6

Male/female

Arthritis

5/2

15/7

9/2

Constitutional

features

Skin rash

19

Ocular disease*

Gastrointestinal

tract diseaset

10

* Iritis, cyclitis, keratoconjunctivitis or retinal infarction.

tGastrointestinal tract haemorrhage; acute colitis or

hepatitis.

Downloaded from qjmed.oxfordjournals.org by guest on February 12, 2011

*No. of patients in parentheses; cyclo = cyclophosphamide; pred = prednisolone;

aza = azathioprine.

78

5. Holdsworth and others

idiopathic glomerulonephritis complicated by lung haemorrhage. Their pulmonary disease could

not be attributed on clinical, radiological or microbiological grounds to left ventricular failure,

pulmonary infection or pulmonary embolism.

Clinical features

The age of the patients ranged from 13 to 76 years (mean 47.5 years). Patients with systemic

vasculitis were significantly older (mean age 54.9 years). Disease was more common in males in

all groups (Table 2).

Patients with vasculitis often had a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations with rash,

arthritis/arthralgia or gastrointestinal or eye abnormalities. Non-specific constitutional symptoms were seen often in patients with idiopathic Goodpasture's syndrome and anti-GBM

disease.

(a) Renal function at presentation. Most patients had advanced renal impairment at the time of

presentation, particularly with anti-GBM disease where the mean creatinine at presentation was

1011 /zmol/1. Patients with vasculitis or idiopathic Goodpasture's syndrome, (although with substantial loss of renal function) had significantly lower mean presenting creatinines (463 and 411

/xM/1 respectively).

TABLE 3. Laboratory features

Anti-GBM

Vasculitis

Idiopathic

Goodpasture's

syndrome

Anti-GBM antibodies

(radio Lmmunoassay)

Hypocomplementaemia

Circulating immune

complexes (positive)

Raised C-reactive

protein

Anaemia (Hb < 10 g

per cent)

ESR> 60mm/h

13

18

Oligoanuria

(< 500 ml/day)

Protein excretion

(g/24h)

4.7

4.1

4.3

Active sediment

Haematuria

21

10

1011

463

411

Presenting creatinine

(mean //M/l)

Downloaded from qjmed.oxfordjournals.org by guest on February 12, 2011

Laboratory findings (Table 3)

Acute Glomerulonephritis

and Lung Haemorrhage (Goodpasture's Syndromej

79

(b) Urinary sediment and protein excretion. Red cell casts and microscopic haematuria were

usually observed. The 24 h excretion of protein did not distinguish between subgroups. Eleven

of the patients were oligo-anuric (urine output less than 500 ml/24 h) at the time of presentation. Of these, seven had anti-GBM disease, two had systemic vasculitis and two idiopathic

Goodpasture's syndrome.

(c) Haematology. Most patients had significant anaemia at the time of presentation, probably

associated with their renal impairment and intrapulmonary blood loss. The presence of anaemia

did not distinguish between the underlying causes. There were no significant differences between

blood film observations and white blood cell counts in the groups (with the exception of the

two patients with intravascular coagulopathy where characteristic red cell changes were observed

and three of the five patients with systemic lupus erythematosus who had neutropenia).

(e) Circulating anti-GBM antibodies. Radioimmunoassay showed the presence of circulating

anti-GBM antibodies in all patients with histological evidence of linear-GBM IgG deposition on

renal biopsy. Radioimmunoassay was negative in all patients in the other aetiological subgroups

(Table 3).

TABLE 4. Pulmonary features of Goodpasture 's syndrome*

Anti-GBM

(7)

Vasculitis

(22)

Idiopathic

(11)

(a) Chest radiographic abnormalities

Diffuse alveolarinterstitial anomaly

6

11

Focal pulmonary

infiltrate

11

(b) Pulmonary complications (immediate)

Acute respiratory

failure

3

5

Fatal pulmonary

haemorrhage

Pneumothorax

Tension cyst

(c) Pulmonary complications (late)

Clinical respiratory

compromise

0/4

1/18

0/10

Chest radiographic

abnormality

0/4

4/18

0/10

Abnormal lung

function test

2/3

5/7

0/2

*No. of patients in parentheses.

Downloaded from qjmed.oxfordjournals.org by guest on February 12, 2011

(d) Evidence of systemic inflammatory response. C-reactive protein levels were in general higher

in patients with anti-GBM disease than in patients with vasculitis or idiopathic Goodpasture's

syndrome.

80

S. Holdsworth and others

(f) Circulating immune complexes. Circulating immune complexes were detected in patients in

all three groups, including two patients with anti-GBM disease.

(g) Other autoantibodies. There was no significant detection of non-kidney autoantibodies

except for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, all of which had positive tests for antinuclear antibodies both by indirect immunofluorescence and by DNA binding assay.

Pulmonary radiological appearances (Table 4)

RENAL HISTOLOGY (Table 5)

(a) Anti-GBM disease. All patients with anti-GBM disease had diffuse proliferative crescentic

glomerulonephritis with 100 per cent crescents. The interstitium was relatively normal, although

an infiltrate was seen in three renal biopsies.

Immunofluorescence findings revealed linear deposition of IgG in all cases and of igM in

three. IgA was not seen in any biopsy. Complement (C3) was present in all glomeruli and was in

a linear (5) or interrupted linear pattern (2). Fibrin deposition was prominent in relation to

crescents. Electron microscopic observations confirmed the diffuse proliferative crescentic

glomerulonephritis. There was relatively little mesangial proliferation.

TABLE 5. Renal histology

Histology

Anti-GBM

Diffuse endocapillary

proliferative

glomerulonephritis

-

Vasculitis

Idiopathic

Goodpasture's

syndrome

Diffuse crescentic

glomerulonephritis

Focal proliferative

glomerulonephritis

Focal necrotising

glome rulonephritis

with crescents

13

Membranoproliferative

glomerulonephritis

with crescents

Downloaded from qjmed.oxfordjournals.org by guest on February 12, 2011

A variety of radiological appearances were observed. These varied from the demonstration of

classical lesions (one patient with Wegener's granulomatosis) to non-specific focal or diffuse

pulmonary infiltrates. The majority of cases of anti-GBM disease had a diffuse pulmonary

abnormality. However, in each aetiological group the pulmonary infiltrate could be either focal

or diffuse, rendering the initial radiographic appearance of limited value in differential diagnosis.

In a retrospective analysis two independent radiologists could not distinguish reliably pulmonary

haemorrhage from other causes of pulmonary infiltration.

Acute Glomendonephritis and Lung Haemorrhage (Goodpasture's Syndrome)

81

(c) Idiopathic Goodpasture's syndrome. A variety of proliferative forms of glomerulonephritis

were present including endocapillary proliferative glomerulonephritis (3); mesangiocapillary

glomerulonephritis type I (1); diffuse crescentic glomerulonephritis (6) and focal proliferative

glomerulonephritis (1). Crescent formation was again prominent in idiopathic Goodpasture's

syndrome (seven of the I 1 patients). Granular or interrupted linear deposition of fibrin was

seen, particularly in relation to areas of crescent formation. Mesangial and loop deposition of

C3, C4, C1Q, IgG and IgM occurred. Only one patient had a biopsy without any immune reactants. The extent of crescentic formation in this patient was 100 per cent and death from

fulminating pulmonary haemorrhage resulted despite steroid and cyclophosphamide treatment

and plasma exchange.

CLINICAL OUTCOME

(a)Mortality (Table 6)

The highest mortality was observed in anti-GBM disease where four of seven patients died

(mean of 3.9 months after presentation). Three died from sepsis and one from acute pulmonary

haemorrhage 24h after admission. Patients with vasculitis also had a significant mortality

(15/22). Patients with secondary vasculitis all died from their underlying disease (mean 3.3

months after presentation). The deaths in patients with primary vasculitis occurred much later

(mean 35 months). Six of these deaths were from sepsis, four from progression of the underlying disease and one death from an unrelated acute myocardial infarct. Four of the 11 patients

with idiopathic Goodpasture's syndrome died, one from fulminating lung haemorrhage a month

after presentation to hospital, the others from complications of dialysis and transplantation

many years after their initial presentation.

(b) Pulmonary sequellae (Table 4)

Fulminating pulmonary haemorrhage was the cause of death in two patients (one with antiGBM disease and one with idiopathic Goodpasture's syndrome). Life-threatening pulmonary

haemorrhage was seen in a further 10 patients, but settled relatively quickly (mean 4.8 days) in

the group as a whole. The duration of pulmonary haemorrhage was: mean 6.3 days for antiGBM disease, mean 5.3 days for vasculitis and mean 2.9 days for idiopathic Goodpasture's

syndrome. Radiological appearances also improved over similar time intervals, although several

Downloaded from qjmed.oxfordjournals.org by guest on February 12, 2011

(b) Vasculitis. The most common finding in this group was a focal and segmental proliferative

and necrotising glomerulonephritis with crescents. This was present in 13 biopsies and was a

common finding regardless of the underlying type of vasculitis. Other histological patterns

included diffuse endocapillary proliferative glomerulonephritis (2), diffuse crescentic glomerulonephritis (5), and focal proliferative glomerulonephritis without crescents (2). Eighteen of the

22 biopsies from patients with vasculitis showed crescent formation. The extent of crescent

formation varied from 15 to 100 per cent. Immunofluorescence findings confirmed variable

granular igG and IgM as well as C3 in glomeruli of all biopsies. This varied in distribution

throughout capillary loops and the mesangium. Fibrin was deposited within Bowman's space in

relation to the formation of crescents, although it was also occasionally seen outlining capillary

loops and mesangia. The four patients with lupus nephritis had prominent immunoglobulin

deposition and very heavy granular staining of capillary loops C3, C4 and Clq. Again interstitial

inflammation was not significant. Electron microscopic appearances confirmed the light microscopy findings.

S. Holdsworth and others

82

TABLE 6. Mortality

Idiopathic

Goodpasture's

syndrome

4/11

Anti-GBM

Vasculitis

Mortality

Mean survival

(months)

4/7

15/22

3.9

Cause of

death

Three sepsis

One lung

haemorrhage

(a) Primary

vasculitis (35)

(b) Secondary

vasculitis (3.3)

(a) Primary (11)

Six sepsis

Four disease

One acute

myocardial infarct

(b) Secondary (4)

disease

60

One lung haemorrhage

One AMI

Two transplantation

complications

patients displayed a residual minor interstitial abnormality for one to three weeks. The major

immediate pulmonary complication was respiratory failure requiring assisted ventilation (12

patients).

Only minor residual abnormalities were found after six months in the survivors (Table 4).

Patients with anti-GBM disease had no symptoms or radiological abnormality but three of four

had diffusion abnormalities (decreased carbon dioxide diffusing capacity (DL C O ) on pulmonary

function testing). Among patients with vasculitis, those with Wegener's granulomatosis had the

worst pulmonary outcome. One had significant exertional dyspnoea and four had radiological

pulmonary scarring. Five of seven vasculitic patients had an abnormal D L c o None of the

patients with idiopathic Goodpasture's syndrome had persisting pulmonary abnormalities.

TABLE 7. Renal outcome in Goodpasture's syndrome*

Acute dialysis

(a) Death < 2/52

(b) On to maintenance

dialysis

(c) Recovery of renal

function

(d) Initial recovery of

renal function and late end

stage renal failure

No acute dialysis

(a) Stable renal function

(b) Eventual end stage renal

failure

Anti-GBM

7

3

4 (980/zM/l)

Vasculitis

4(955AIM/1)

Idiopathic

3(985MM/1)

4(550MM/1)

2 [8.5 months]

11

6(345MM/1)

5 (680/iM/l)

[12.1 months]

6(247juM/l)

1 (740MM/1)

[6.7 months]

*Figures in parentheses represent the mean serum creatinine at the time of initial

presentation to hospital of each patient subpopulation; figures in square brackets

represent the mean time between initial presentation to hospital and the commencement of maintenance dialysis.

Downloaded from qjmed.oxfordjournals.org by guest on February 12, 2011

Patients

Acute Glomendonephritis and Lung Haemorrhage (Goodpasture 's Syndrome)

83

RENAL FUNCTION (Table 7)

DISCUSSION

This study emphasises that a variety of different diseases can lead to acute glomerulonephritis

and lung haemorrhage, the combination of presenting features originally designated as Goodpasture's syndrome by Stanton and Tange (2). Recognition of the pathogenetic role of antiGBM antibodies in a subpopulation of patients with Goodpasture's syndrome led to a suggestion that the term be restricted to patients with the triad of anti-GBM antibodies, acute nephritis

and lung haemorrhage. As this restriction is not universally accepted, use of the term Goodpasture's syndrome now often leads to confusion. A resolution of this dilemma would be to use

the eponym 'Goodpasture's syndrome' to describe the clinical association of acute nephritis and

lung haemorrhage but not to regard it as an aetiological diagnosis. Such usage would designate a

clinical syndrome with dire potential consequences and alert clinicians to perform appropriate

investigations into the underlying disease.

In this study anti-GBM disease was present in only 28 per cent of patients. The majority of

patients had diseases probably related to immune-complex deposition. Diseases in this category

known to present with Goodpasture's syndrome include Wegener's granulomatosis (5), systemic

lupus erythematosis (10, 11, 18), cryoglobulinaemia (18) and a variety of others (9, 10, 17).

A significant number of our patients (11 of 40) had no underlying systemic disease or antiGBM antibody association and therefore had primary/idiopathic glomerulonephritis with

primary/idiopathic lung haemorrhage. We believe their designation as cases of 'idiopathic Goodpasture's syndrome' is thus appropriate. Ten of these 11 patients had evidence of immune reactants being deposited in glomeruli, so that immune mechanisms could be suggested as producing

injury. One patient however had no immune reactants and no underlying systemic disease thus

having 'idiopathic' Goodpasture's syndrome from both aetiological and immunopathogenic

points of view. Incidence of immune reactant negative crescentic nephritis varies widely ( 2 1 24), some regarding it as an important clinical entity (22) while others doubt its existence (24).

Review of the clinical features of the patients in the current study show that it is often not

possible to make the diagnosis of the disease presenting as Goodpasture's syndrome on clinical

Downloaded from qjmed.oxfordjournals.org by guest on February 12, 2011

The need for early dialysis was defined as initiation within two weeks of presentation. All of

the patients with anti-GBM disease required early haemodialysis. No patient in this category

regained renal function sufficiently to allow withdrawal of dialysis. Of the 22 patients with

systemic vasculitis 11 required early dialysis. Four patients (mean presenting creatinine 550 AIM/I)

could be withdrawn from dialysis following treatment of their underlying diseases, although

two of these then had progressive renal impairment and eventually required chronic dialysis

(mean 8.5 months after presentation). Of the four patients with idiopathic Goodpasture's syndrome who required early dialysis none recovered renal function before death.

Fifty per cent (11/22) of patients with systemic vasculitis did not require early dialysis.

These were divided into two groups on the basis of their renal outcome. Six patients (mean

presenting creatinine 345/iM/l) remain with stable renal function throughout the period of

follow-up (mean 37.4 months). Five patients (mean presenting creatinine 680fjM/\) have progressed to early stage renal failure (mean 12.1 months from presentation), despite treatment of

their vasculitis.

Of the patients with idiopathic Goodpasture's syndrome, only one (presenting creatinine

740 iiM/\) of those not requiring early dialysis has progressed to early stage renal failure (over 6.7

months). In six (mean presenting creatinine 247 iM/l) renal function is stable.

84

S. Holdsworth and others

Downloaded from qjmed.oxfordjournals.org by guest on February 12, 2011

grounds alone. With the exceptions of anti-GBM antibody radioimmunoasay and renal biopsy,

laboratory investigations were of little help in determining the underlying diseases. Serum antiGBM antibody determination by radioimmunoassay distinguished clearly between anti-GBM

disease and the other causes of Goodpasture's syndrome. The indices commonly recognised as

typical of vasculitic illness (e.g. the presence of circulating immune complexes, raised C-reactive

proteins and raised ESR) were not useful in defining the presence of a vasculitis. Most patients

were severely anaemic and had a raised ESR regardless of the underlying disease. Immune

complexes were found as often in the patients with idiopathic glomerulonephritis as they were

in patients with systemic vasculitis.

The chest radiograph provided surprisingly little assistance with differential diagnosis. It was

not possible to distinguish reliably between pulmonary haemorrhage and other causes of pulmonary infiltration. There was no characteristic radiological appearance which differentiated

anti-GBM disease from systemic vasculitis or idiopathic Goodpasture's syndrome. The exception to this generalisation occurred in a single patient with Wegener's granulomatosis showing

typical cavitating lesions at the time of presentation.

The renal histology revealed a variety of acute proliferative glomerulonephritides. The renal

histology was of value in the diagnosis of anti-GBM disease with characteristic linear staining of

the basement membrane with IgG or IgM. Similarly, focal and segmental necrotising cr*scentic

proliferative glomerulonephritis was usually found in patients with systemic vasculitis. This

picture was not pathognomic of a vasculitis, but was so commonly found as to make the

presence of this histological finding in a patient with Goodpasture's syndrome highly suggestive

of an underlying systemic vasculitis. It should promote a thorough reassessment of the patient

particularly looking for evidence of a vasculitis, including histological assessment of other

organ systems (e.g. skin, liver, muscle or lung). Less useful in differential diagnosis was the

the presence of focal proliferative glomerulonephritis alone or diffuse proliferation with crescents. These findings could occur with a variety of underlying diseases.

The overall outcome for patients in this study was extremely poor. We believe the major

reason for this was that most patients presented with advanced renal failure. Mortality was

contributed to by aggressive immunosuppressive therapy (used in an attempt to reverse renal

impairment and control pulmonary haemorrhage) and sepsis was the single most important

cause of death.

We found three features which predict a poor prognosis. The first is a creatinine level greater

than 600;uM/l at presentation. Patients in this category had the worst prognosis, with only one

of 24 coming off dialysis. As a group, 12 of the 24 died within a year. The second, related

adverse prognostic factor was oligoanuria. The third feature implying a poor prognosis was

more than 50 per cent crescents (shown by renal biopsy). Such patients had a rapid progression

to renal failure regardless of the underlying disease, requiring dialysis or transplantation (14 of

16 such patients required dialysis within 12 months). There is general agreement in the literature

that these three features indicate a poor prognosis (22, 2528) although the recent review of

Hind et al. (25) suggests that in the non anti-GBM group this pessimistic attitude may not be

appropriate.

The response to treatment of the diseases leading to Goodpasture's syndrome is highly variable.

The current series confirms that treatment should await diagnosis of the underlying disease,

since tumours and bacterial infections (e.g. subacute bacterial endocarditis) as well as 'autoimmune diseases' may be responsible for acute: glomerulonephritis and pulmonary haemorrhage.

In our series the patients with anti-GBM disease (all oligoanuric, all 100 per cent crescentic

glomerulonephritic, mean presenting Cr 1101 /iM/l) did poorly. In none did renal function

recover, and three of seven died early from sepsis, related in part to immunosuppression. In the

recent report of Hind et al. (25) renal function did not recover in 21 patients with anti-GBM

Acute Glomerulonephritis and Lung Haemorrhage (Goodpasture 's Syndrome)

85

CONCLUSION

The study shows that the prognosis is poor for a patient presenting with acute nephritis and

pulmonary haemorrhage. The syndrome, originally defined as Goodpasture's syndrome, may be

due to a variety of underlying diseases. The designation 'Goodpasture's syndrome' is not

recommended as a final diagnosis. Adequate management requires that the disease underlying

Goodpasture's syndrome becomes the primary diagnosis. The study points out the significant

morbidity and mortality of diseases that present as Goodpasture's syndrome though many of

these diseases are reversible if recognised early. It is recommended that with the development of

anuria or an initial serum creatinine > 600^M/l the option of dialysis alone, without immunosuppression, be considered unless pulmonary haemorrhage is significant. Renal histology is

useful both in the diagnosis of the underlying disease and in predicting the prognosis. The

application of radioimmunoassy for the detection of anti-GBM antibodies is a significant advance,

providing a non-invasive, rapid means of making a definite diagnosis.

REFERENCES

1. Wilson CB, Dixon F. The pathogenesis of renal disease. In: The Kidney (Eds. Brenner BM,

Rector FC), Vol. 1, 1 256. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1981.

2. Stanton MC, Tange JD. Goodpasture's syndrome (pulmonary haemorrhage associated with

glomerulonephritis). Aust Ann Med 1958; 7: 132-144.

3. Goodpasture EW. The significance of certain pulmonary lesions in relation to the etiology

of influenza. Am J Med Sci 1919; 1 58: 863-870.

4. Lerner RA, Glassock KJ, Dixon FJ. The role of antiglomerular basement membrane antibody in the pathogenesis of human glomerulonephritis. J Exp Med 1976; 126: 989 1004.

5. Glassock RJ. A clinical and immunopathologic dissection of rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. Nephron 1978; 22: 253-264.

6. Fauci AS, Haynes BF, Kataz P, Wolff SM. Wegener's granulomatosis: prospective clinical

and therapeutic experience with 85 patients for 21 years. Ann Intern Med 1983; 98: 76

85.

7. Hunninghakae GW, Fauci AS. Pulmonary involvement in the collagen vascular diseases. Am

Rev RespirDis 1979; 119: 4 7 1 - 5 0 3 .

8. Thomas HM, Irwin RS. Classicication of diffuse intrapulmonary haemorrhage. Chest 1975;

68: 483-484.

9. Martinez JS, Kohler PF. Variant 'Goodpasture's syndrome'? Ann Intern Med 1971; 75:

67-75.

Downloaded from qjmed.oxfordjournals.org by guest on February 12, 2011

disease despite treatment with intensive plasma exchange, steroids and cytotoxic drugs. Our

observations taken together with the other reports of failure to recover renal function by anuric

patients with anti-GBM disease (27, 29) make it reasonable to advocate that active immunosuppression should be offered to patients presenting with anti-GBM disease requiring dialysis

only if life-threatening lung haemorrhage is present.

The outcome for patients in the vasculitis group was also poor. Although short-term response

to immunosuppression was better (with four of 11 dialysis-requiring patients showing improvement in renal function sufficient to allow cessation of dialysis) the overall mortality in this

group was high, with half the late deaths related to infection. The vasculitis patients may respond

to immunosuppression and plasma exchange, although a favourable outcome in terms of preservation of life and restoration of renal function occurred in less than a third of patients in reported

series (3035). The presence of advanced renal failure at presentation and crescentic glomerulonephritis are thought to carry a poor prognosis (23, 2628). Patients with idiopathic Goodpasture's syndrome had the best outcome. These patients also had less immunosuppressive

therapy, only two of 11 being given cytotoxic drugs.

86

S. Holdsworth and others

Downloaded from qjmed.oxfordjournals.org by guest on February 12, 2011

10. Parkin TW, Rusted IE, Burchell HB et al. Haemorrhagic and interstitial pneumonitis with

nephritis. Am J Med 1955; 18: 220-228.

11. Thomashow BM, Felton CP, Navarro C. Diffuse pulmonary haemorrhage, renal failure and

a systemic vasculitis. Am J Med 1980;68: 229-304.

12. Purneell DC, Baggenstosis AH, Olsen AM. Pulmonary lesions in disseminated lupus erythematosus. Ann Intern Med 1 955 ;42: 619.

13. Lewis EJ, Schur PH, Busch GJ, Galvanek E, Merrill JP. Immunopathologic features of a

patient with glomerulonephritis and pulmonary haemorrhage. Am J Med 1973; 54: 507

513.

14. Gould DB, Soriano RZ. Acute alveolar haemorrhage in lupus erythematosus. Ann Intern

Med 1973; 83: 836-837.

15. Eagen JW, Memoli VA, Roberts JL, Matthew GR, Schwartz MM, Lewis EJ. Pulmonary

haemorrhage in systemic lupus erythematosus. Medicine (Baltimore) 1978; 57: 545560.

16. Mintz G, Galindo LF, Fernandez-Diez J, Jimenez FJ, Robles-Saavendra E, EnruiquezCasillas RD. Acute massive pulmonary haemorrhage in systemic lupus erythematosus. J

Rheumatol 1978; 5: 39-50.

17. Marino CT, Pertschuk LP. Pulmonary haemorrhage in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch

Intern Med 1981; 141: 201-203.

18. Leatherman JW, Sibley RK, Davis SF. Diffuse intrapulmonary haemorrhage and glomerulonephritis unrelated to anti-glomerular basement membrane antibody. Am J Med 1982;

72: 401-410.

19. Holdsworth SR, Wischusen NJ, Dowling JP. A radioimmunoassay for the detection of

circulating anti-glomerular basement mebrane antibodies. Aust NZ J Med 1983; 13: 1520.

20. Fauci AS, Haynes BF, Katz P. The spectrum of vasculitis: clinical, pathological, immunologic

and therapeutic considerations. Ann Intern Med 1978; 89: 660676.

21. Beirne GJ, Wagnild JP, Zimmerman SW, Macken PD, Burkholder PM. Idiopathic crescentic

glomerulonephritis. Medicine (Baltimore) 1977; 56: 349-381.

22. Stilman MM, Bolton WK, Sturgill BC, Schmitt GW, Couser WG. Crescentic glomerulonephritis without immune deposits. Clinicopathologic features. Kidney Int 1979; 15: 184 195.

23. Whitworth JA, Morel-Maroiger L, Mignon F, Richet G. The significance of extracapillary

proliferation. Clinicopathological review of 60 patients. Nephron 1976; 16: 1 19.

24. Cohen AH, Border WA, Shankel E, Glassock KJ. Crescentic glomerulonephritis: immune vs

non immune mechanisms. Am J Nephrol 1981; 1: 7883.

25. Hind CRK, Paraskevakou H, Lockwood CM, Evans DJ, Peters DK, Rees AJ. Prognosis after

immunosuppression of patients with crescentic nephritis requiring dialysis. Lancet 1983 ; 1:

263-265.

26. Morrin PAF, Hinglasis N, Nabarra B, Kreis H. Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis: a

clinical and pathologic study. Am J Med 1978; 65: 446-460.

27. Spargo BH, Ordonez NG, Ringus JC. The differential diagnosis of crescentic glomerulonephritis: the pathology of specific lesions with prognostic implications. Hum Pathol 1977;

8: 187-204.

28. McLeish KR, Yum MN, Kluft PC. Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis in adults: clinical

and histologic correlation. Clin Nephrol 1978; 10: 43-50.

29. Kincaid-Smith P, d'Apice AJF. Plasmapheresis in rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis.

Am J Med 1978; 65: 564-566.

30. Leonard CD, Nagle RB, Striker GE, Cutler RE, Scribner BH. Acute glomerulonephritis

with prolonged oliguria. Ann Int Med 1970; 73: 703-711.

31. Sonsino E, Nabarra B, KazatchJcine M, Hinglais N, Kreia H. Extracapillary proliferative

glomerulonephritis. Adv Nephrol 1972; 2: 121-163.

32. Brown CB, Turner D, Ogg CS et al. Combined immunosuppression and anticoagulation in

rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. Lancet 1974; 2: 11661172.

33. Lockwood CM, Pearson TA, Rees AJ, Evans DJ, Peters DK. Immunosuppression and

plasma exchange in the treatment of Goodpasture's syndrome. Lancet 1 979; 1: 7711771 5.

34. Bolton WK, Couser WG. Intravenous pulse methylprednisolone therapy of acute crescentic

rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. Am J Med 1979;66: 495601.

35. Lockwood CM, Pusey CD, Rees AJ, Peter DK. Plasma exchange in the treament of immune

complex disease. Clin Immun A Allergy 1981; 1: 433455.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Tuberculosis in Patients On DialysisDokument5 SeitenTuberculosis in Patients On Dialysisvasarhely imolaNoch keine Bewertungen

- SPMJCTSDokument4 SeitenSPMJCTSKobayashi MaruNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hep Chiv Renal DZDokument9 SeitenHep Chiv Renal DZSundar RamanathanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letters To The Editor: Membranous Glomerulonephritis in A Patient With SyphilisDokument2 SeitenLetters To The Editor: Membranous Glomerulonephritis in A Patient With SyphilisBetty Romero BarriosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alveolar Hemorrhage in SLE0Dokument10 SeitenAlveolar Hemorrhage in SLE0Fabian Aguilar CastilloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sarcoidosis Review. JAMADokument9 SeitenSarcoidosis Review. JAMARafael ReañoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clinical Profile, Etiology, and Management of Hydropneumothorax: An Indian ExperienceDokument5 SeitenClinical Profile, Etiology, and Management of Hydropneumothorax: An Indian ExperienceSarah DaniswaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Report and Literature Review On Good's Syndrome, A Form of Acquired Immunodeficiency Associated With ThymomasDokument7 SeitenCase Report and Literature Review On Good's Syndrome, A Form of Acquired Immunodeficiency Associated With ThymomasMudassar SattarNoch keine Bewertungen

- 8156 29309 1 PBDokument5 Seiten8156 29309 1 PBEden LacsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Seronegative Myasthenia Gravis Presenting With PneumoniaDokument4 SeitenSeronegative Myasthenia Gravis Presenting With PneumoniaJ. Ruben HermannNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tomographic Findings of Acute Pulmonary Toxoplasmosis in Immunocompetent PatientsDokument5 SeitenTomographic Findings of Acute Pulmonary Toxoplasmosis in Immunocompetent Patientshasbi.alginaaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Annsurg00166 0011Dokument8 SeitenAnnsurg00166 0011Muhammad FadillahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Salmonealla Hepatitis in IranDokument3 SeitenSalmonealla Hepatitis in IranWawan BwNoch keine Bewertungen

- Globulin Thyroid Dialy-: TherapyDokument5 SeitenGlobulin Thyroid Dialy-: TherapyNurdita KartikaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Autoantibodies Against Complement C1q Correlate With The Thyroid Function in Patients With Autoimmune Thyroid DiseaseDokument6 SeitenAutoantibodies Against Complement C1q Correlate With The Thyroid Function in Patients With Autoimmune Thyroid DiseaseSaad MotawéaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Respiratory and Pulmonary Medicine: ClinmedDokument3 SeitenRespiratory and Pulmonary Medicine: ClinmedGrace Yuni Soesanti MhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pulmonary Tuberculosis in Patients With Chronic Renal Failure at Zagazig University HospitalsDokument6 SeitenPulmonary Tuberculosis in Patients With Chronic Renal Failure at Zagazig University HospitalsAnastasia Lilian SuryajayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal Maju DR ArifDokument6 SeitenJurnal Maju DR ArifRefta Hermawan Laksono SNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2008.clin Chem - RantnerDokument7 Seiten2008.clin Chem - RantnertwkangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abdominal Tuberculosis in Nepal Medical College Teaching Hospital, KathmanduDokument4 SeitenAbdominal Tuberculosis in Nepal Medical College Teaching Hospital, KathmanduSavitri Maharani BudimanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Surgical Treatment of Primary Hyperparathyroidism: Clinical StudyDokument4 SeitenSurgical Treatment of Primary Hyperparathyroidism: Clinical StudyDala VWNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pathogenesis and Diagnosis of Anti-GBM Antibody (Goodpasture's) DiseaseDokument18 SeitenPathogenesis and Diagnosis of Anti-GBM Antibody (Goodpasture's) DiseaseDicky SangadjiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chronic Cavitary and Fibrosing Pulmonary and Pleural Aspergillosis: Case Series, Proposed Nomenclature Change, and ReviewDokument16 SeitenChronic Cavitary and Fibrosing Pulmonary and Pleural Aspergillosis: Case Series, Proposed Nomenclature Change, and ReviewYassine EssNoch keine Bewertungen

- Significado Clinico de Impactacion Mucosa de Alta Atenuacion en ABPADokument10 SeitenSignificado Clinico de Impactacion Mucosa de Alta Atenuacion en ABPAGonzalo LealNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Case of Lupus Pneumonitis Mimicking As Infective PneumoniaDokument4 SeitenA Case of Lupus Pneumonitis Mimicking As Infective PneumoniaIOSR Journal of PharmacyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Efusi Pleural in MassDokument4 SeitenEfusi Pleural in MassRofi IrmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prolonged Fever Occurring During Treatment of Pulmonary Tuberculosis - An Investigation of 40 CasesDokument3 SeitenProlonged Fever Occurring During Treatment of Pulmonary Tuberculosis - An Investigation of 40 Casesসোমনাথ মহাপাত্রNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ef en HemicigotosDokument11 SeitenEf en HemicigotosHenrik BohrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Study and Care Plan FinalDokument19 SeitenCase Study and Care Plan Finalapi-238869728100% (2)

- Oxford University PressDokument9 SeitenOxford University PresssarafraunaqNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1quarterly Journal of Medicine, 1993Dokument8 Seiten1quarterly Journal of Medicine, 1993Maha OmarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pulmonary Hemorrhage in Henoch-Schönlein Purpura: Case Report and Systematic Review of The English LiteratureDokument10 SeitenPulmonary Hemorrhage in Henoch-Schönlein Purpura: Case Report and Systematic Review of The English LiteratureIwan MiswarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hyponatremia and Anti-Diuretic Hormone in Legionnaires ' DiseaseDokument9 SeitenHyponatremia and Anti-Diuretic Hormone in Legionnaires ' DiseasejuanpbagurNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fibrinogen Catabolism in Systemic Erythematosus: LupusDokument4 SeitenFibrinogen Catabolism in Systemic Erythematosus: LupusRazvanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tuberculosis and Chronic Renal FailureDokument38 SeitenTuberculosis and Chronic Renal FailureGopal ChawlaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 54 Shivraj EtalDokument3 Seiten54 Shivraj EtaleditorijmrhsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hyperbilirubinemia: A Risk Factor For Infection in The Surgical Intensive Care UnitDokument14 SeitenHyperbilirubinemia: A Risk Factor For Infection in The Surgical Intensive Care UnitChristian Karl B. LlanesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Early Atherosclerotic Changes in The Patients With Idiopathic Epilepsyegyptian Preliminary Study 2472 0895 1000112Dokument6 SeitenEarly Atherosclerotic Changes in The Patients With Idiopathic Epilepsyegyptian Preliminary Study 2472 0895 1000112Luther ThengNoch keine Bewertungen

- HANTAVIRUS Case Report - Trud Za ObjavuvanjeDokument7 SeitenHANTAVIRUS Case Report - Trud Za ObjavuvanjeKeti JanevskaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wegener SDokument7 SeitenWegener SJeffrey Ian M. KoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ann Rheum Dis-1989-Rodrigué-424-7Dokument5 SeitenAnn Rheum Dis-1989-Rodrigué-424-7Saad MotawéaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Alcohol Abuse and Unusual Abdominal Pain in A 49-Year-OldDokument7 SeitenCase Alcohol Abuse and Unusual Abdominal Pain in A 49-Year-OldPutri AmeliaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Perm State Medical University Churg-Strauss Syndrome: - Joisy Aloor 5 YearDokument33 SeitenPerm State Medical University Churg-Strauss Syndrome: - Joisy Aloor 5 YearOlga GoryachevaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Case of Mushroom Poisoning With Russula Subnigricans: Development of Rhabdomyolysis, Acute Kidney Injury, Cardiogenic Shock, and DeathDokument4 SeitenA Case of Mushroom Poisoning With Russula Subnigricans: Development of Rhabdomyolysis, Acute Kidney Injury, Cardiogenic Shock, and DeathsuserNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adler 2015Dokument7 SeitenAdler 2015nathaliepichardoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mortality in Typhoid Intestinal Perforation-A Declining TrendDokument3 SeitenMortality in Typhoid Intestinal Perforation-A Declining Trendaura009Noch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal Microsatelie 2Dokument7 SeitenJurnal Microsatelie 2Ieien MuthmainnahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cushing SubDokument7 SeitenCushing SubClaudia IrimieNoch keine Bewertungen

- EmpyemaDokument3 SeitenEmpyemaAstari Pratiwi NuhrintamaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letter To The Editor Henoch-Schönlein Purpura in Adults: Clinics 2008 63 (2) :273-6Dokument4 SeitenLetter To The Editor Henoch-Schönlein Purpura in Adults: Clinics 2008 63 (2) :273-6donkeyendutNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acute Pyelonephritis in Adults: A Case Series of 223 PatientsDokument6 SeitenAcute Pyelonephritis in Adults: A Case Series of 223 PatientsshiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jeffrey L Carson Restrictive or Liberal TransfusionDokument11 SeitenJeffrey L Carson Restrictive or Liberal Transfusionmiguel aghelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pleural Effusion in A Patient With End-Stage Renal Disease - PMCDokument5 SeitenPleural Effusion in A Patient With End-Stage Renal Disease - PMCCasemix rsudwaledNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rol de La PlasmaferesisDokument2 SeitenRol de La PlasmaferesisLuis Hernán Guerrero LoaizaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Early Intervention Can Improve Clinical Outcome of Acute Interstitial PneumoniaDokument9 SeitenEarly Intervention Can Improve Clinical Outcome of Acute Interstitial PneumoniaHerbert Baquerizo VargasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Activity No 2 ImmunohematologyDokument3 SeitenActivity No 2 ImmunohematologyAegina FestinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chest Radiographic Manifestations of Scrub Typhus - PMCDokument9 SeitenChest Radiographic Manifestations of Scrub Typhus - PMCSurachai PraimaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gastrite Enfisematosa - InglêsDokument7 SeitenGastrite Enfisematosa - Inglêsamanda.gomesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Barth SyndromeDokument4 SeitenBarth SyndromeC_DanteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 6: Liver and GallbladderVon EverandComplementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 6: Liver and GallbladderNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evidence Based Practice Guidelines For The Nutritional Management of Chronic Kidney Disease.Dokument12 SeitenEvidence Based Practice Guidelines For The Nutritional Management of Chronic Kidney Disease.Sa 'ng WijayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Katrina Louise Campbell ThesisDokument253 SeitenKatrina Louise Campbell ThesisSa 'ng WijayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- One-Sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov TestDokument15 SeitenOne-Sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov TestSa 'ng WijayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Amniotic Membrane Transplantation For Primary Pterygium SurgeryDokument5 SeitenAmniotic Membrane Transplantation For Primary Pterygium SurgerySa 'ng WijayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Epidemiology of Gastric Cancer and Helicobacter Pylori: Jonathan Volk and Julie ParsonnetDokument34 SeitenEpidemiology of Gastric Cancer and Helicobacter Pylori: Jonathan Volk and Julie ParsonnetSa 'ng WijayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management of Gastric Variceal Hemorrhage: S K Sarin, Sanjay NegiDokument4 SeitenManagement of Gastric Variceal Hemorrhage: S K Sarin, Sanjay NegiSa 'ng WijayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- HP94 04 PredictingDokument8 SeitenHP94 04 PredictingSa 'ng WijayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alport's Syndrome, Goodpasture's Syndrome, and Type IV CollagenDokument14 SeitenAlport's Syndrome, Goodpasture's Syndrome, and Type IV CollagenSa 'ng WijayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 200672460493205Dokument6 Seiten200672460493205Sa 'ng WijayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5 16Dokument12 Seiten5 16Sa 'ng WijayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Probiotics Can Treat Hepatic Encephalopathy: S. F. SolgaDokument7 SeitenProbiotics Can Treat Hepatic Encephalopathy: S. F. SolgaSa 'ng WijayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Molecular Architecture of The Goodpasture Autoantigen in Anti-GBM NephritisDokument12 SeitenMolecular Architecture of The Goodpasture Autoantigen in Anti-GBM NephritisSa 'ng WijayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Campak 11 PDFDokument12 SeitenCampak 11 PDFSa 'ng WijayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 07-MAKALAH - Prof DR DR Ismoedijanto SpA (K)Dokument41 Seiten07-MAKALAH - Prof DR DR Ismoedijanto SpA (K)Anay TullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- DBD Fever and RashDokument11 SeitenDBD Fever and RashSa 'ng WijayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bacteria Vs Viruses and DiseasesDokument38 SeitenBacteria Vs Viruses and DiseasesNha HoangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Msds PG LyondellDokument9 SeitenMsds PG LyondellGia Minh Tieu TuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ethical Judgments Limit The Methods Available in The Production of Knowledge in Both The Arts and The Natural SciencesDokument5 SeitenEthical Judgments Limit The Methods Available in The Production of Knowledge in Both The Arts and The Natural SciencesMilena ŁachNoch keine Bewertungen

- Phylum PlatyhelminthesDokument19 SeitenPhylum PlatyhelminthesBudi AfriyansyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Define Education: Why Education Is Important To SocietyDokument5 SeitenDefine Education: Why Education Is Important To SocietyzubairNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ulcerative ColitisDokument30 SeitenUlcerative ColitisAndika SulistianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hea LLG: 18 Sign of Dehydration - ThirstDokument22 SeitenHea LLG: 18 Sign of Dehydration - ThirstMhae TabasaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journal Pone 0208697 PDFDokument14 SeitenJournal Pone 0208697 PDFRenzo Flores CuadraNoch keine Bewertungen

- More Reading Power PP 160-180Dokument21 SeitenMore Reading Power PP 160-180kenken2Noch keine Bewertungen

- Liver CancerDokument16 SeitenLiver CancerMark James MelendresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Autoimmune Abnormalities of Postpartum Thyroid DiseasesDokument8 SeitenAutoimmune Abnormalities of Postpartum Thyroid DiseasesIpan MahendriyansaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Occlusion - DevelopmentDokument33 SeitenOcclusion - Developmentsameerortho100% (1)

- DEV2011 2018 Practical Week 8 DRAFT REPORT PDFDokument1 SeiteDEV2011 2018 Practical Week 8 DRAFT REPORT PDFAreesha FatimaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ulibas V Republic - DigestDokument2 SeitenUlibas V Republic - DigesttheamorerosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 11.21 - Maternal Health Status in The PhilippinesDokument7 Seiten11.21 - Maternal Health Status in The PhilippinesJøshua CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Diet Solution Metabolic Typing TestDokument10 SeitenThe Diet Solution Metabolic Typing TestkarnizsdjuroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Physiology Paper 1 Question BankDokument8 SeitenPhysiology Paper 1 Question BankVeshalinee100% (1)

- Health Crisis Slams Disney, But More Bloodletting Ahead: For Personal, Non-Commercial Use OnlyDokument30 SeitenHealth Crisis Slams Disney, But More Bloodletting Ahead: For Personal, Non-Commercial Use OnlyMiguel DiazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Topnotch Practice Exam 1 For MARCH 2020 and SEPT 2020 BatchesDokument104 SeitenTopnotch Practice Exam 1 For MARCH 2020 and SEPT 2020 BatchesJerome AndresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Volunteer Report FinalDokument11 SeitenVolunteer Report FinalBeenish JehangirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lifespan: Why We Age - and Why We Don't Have To - DR David A. SinclairDokument5 SeitenLifespan: Why We Age - and Why We Don't Have To - DR David A. Sinclairtidasesu0% (1)

- Disease Signs & SymptomsDokument3 SeitenDisease Signs & SymptomsJose Dangali AlinaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jadwal Pir MalangDokument4 SeitenJadwal Pir MalangAbraham BayuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Metabolic Encephalopathies in The Critical Care Unit: Review ArticleDokument29 SeitenMetabolic Encephalopathies in The Critical Care Unit: Review ArticleFernando Dueñas MoralesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Paper Herbal MedicineDokument4 SeitenResearch Paper Herbal Medicineaflbtlzaw100% (1)

- 5 Day Fast by Bo Sanchez PDFDokument14 Seiten5 Day Fast by Bo Sanchez PDFBelle100% (1)

- Symbolism in The Masque of The Red DeathDokument8 SeitenSymbolism in The Masque of The Red DeathmihacryssNoch keine Bewertungen

- Msds Rheomax DR 1030 enDokument9 SeitenMsds Rheomax DR 1030 enBuenaventura Jose Huamani TalaveranoNoch keine Bewertungen

- RITM LeprosyDokument3 SeitenRITM LeprosyDanielle Vince CapunoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Logbookgazett MOHDokument56 SeitenLogbookgazett MOHShima OnnNoch keine Bewertungen