Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Matilde R. Ramirez de Arellano v. Jose A. Alvarez de Choudens, Etc., 575 F.2d 315, 1st Cir. (1978)

Hochgeladen von

Scribd Government DocsOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Matilde R. Ramirez de Arellano v. Jose A. Alvarez de Choudens, Etc., 575 F.2d 315, 1st Cir. (1978)

Hochgeladen von

Scribd Government DocsCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

575 F.

2d 315

Matilde R. RAMIREZ de ARELLANO, Plaintiff, Appellee,

v.

Jose A. ALVAREZ de CHOUDENS, etc., Defendant, Appellant.

No. 77-1274.

United States Court of Appeals,

First Circuit.

Argued Feb. 9, 1978.

Decided May 10, 1978.

Candita R. Orlandi, Asst. Sol. Gen., San Juan, P. R., with whom Hector

A. Colon Cruz, Sol. Gen., San Juan, P. R., was on brief, for defendant,

appellant.

Alfonso M. Christian, San Juan, P. R., with whom Jose Ramon Perez

Hernandez, San Juan, P. R., was on brief, for plaintiff, appellee.

Before CAMPBELL, BOWNES and MOORE, * Circuit Judges.

LEVIN H. CAMPBELL, Circuit Judge.

This appeal in an action brought under 42 U.S.C. 1983 raises the question of

what statute of limitations applies in Puerto Rico to a commonwealth

employee's claim to have been discharged in violation of constitutional rights.

Because we believe the district court misapplied the tolling provisions of the

relevant statute, we reverse its judgment in favor of plaintiff and order the suit

dismissed.

Matilde R. Ramirez de Arellano filed her complaint on November 15, 1974,

charging Jose A. Alvarez de Choudens, Secretary of Health for Puerto Rico,

and various other officials with conspiring to alter her employment status from

permanent to probationary for political reasons and in violation of due process.

She also charged the officials with infringing her constitutional rights by

subsequently discharging her from her post. Defendants raised the statute of

limitations as an affirmative defense in their answer. After a bench trial, the

district court on March 25, 1977 entered judgment for all the defendants except

Alvarez de Choudens, ordered the reinstatement of Ramirez de Arellano in the

Puerto Rico Civil Service, denied damages, but ordered the payment of $5,000

attorneys' fees to Ramirez de Arellano. Alvarez de Choudens appeals from the

judgment for reinstatement and attorneys' fees. The judgment has been stayed

pending appeal.

3

Plaintiff was appointed to a permanent position as an executive in the Puerto

Rico Department of Health on December 1, 1972. In order to avoid the

probationary period required for such appointments by Puerto Rico law, the

Department obtained a ruling from the Commonwealth's Office of Personnel

that plaintiff could be credited with time worked in a previous position where

she had served under contract rather than as a regular civil service employee.

On January 1, 1973, defendant became Secretary of Health. On February 6 he

requested a ruling from the Office of Personnel as to the legality of the waiver

of plaintiff's probationary period, and on April 6 was advised that the credit

was improper and should be disallowed. An official in the Department wrote

plaintiff on April 13, informing her of her change in status and placing her on

probation until November 30. Plaintiff filed an appeal of that decision with the

Commonwealth's Personnel Board on May 4. The Board on the basis of written

submissions but without holding a face-to-face hearing upheld the change in

plaintiff's status in a decision issued June 27. No direct judicial review of the

Board's action was available. P.R.Laws Ann. tit. 3, 646(a)(6).

Apparently in anticipation of adverse action, plaintiff on September 6, 1973,

filed suit in the superior court seeking a writ of mandamus compelling the

department not to dismiss her. On November 16 she was informed her services

were unsatisfactory and she would not be hired permanently. She appealed that

decision to the Personnel Board on November 26. The Personnel Board

dismissed the appeal on February 12, 1974, and plaintiff obtained a voluntary

dismissal of her suit in the superior court on May 21. The complaint in the

present suit was filed in federal district court on November 15, 1974.

The district court ruled that plaintiff had not made out a claim of political

harassment and dismissed her suit against all the defendants except Alvarez de

Choudens. It held that her dismissal by itself was proper, inasmuch as a

probationary employee had no constitutionally cognizable property interest in

his employment; accordingly her only claim for relief rested on the change in

her tenure status on April 13, 1973. Although the federal suit was brought more

than a year after this event, the court ruled that her mandamus suit in the

superior court had tolled the statute of limitations. On the merits, the court

ruled that the Commonwealth's failure to accord plaintiff a hearing before the

change in her status violated the fourteenth amendment. The court ordered

plaintiff's reinstatement in the Department of Health but refused to award

damages in view of what it found to be defendant's good faith throughout the

dispute. It taxed the Commonwealth with $5,000 in attorneys' fees, however,

because of what it found to be the "obdurate obstinacy" with which Alvarez de

Choudens had defended the suit.

6

In Graffals v. Garcia, 550 F.2d 687 (1st Cir. 1977), this court affirmed the

determination of the United States District Court for Puerto Rico, 415 F.Supp.

19 (1976), that the analogous state statute of limitations for 1983 suits

grounded on a claim of unconstitutional discharge was that found in P.R.Laws

Ann. tit. 31, 5298(2), governing tort actions. This court further held that the

one year period provided by 5298(2) would not be tolled by an administrative

appeal of the dismissal, inasmuch as P.R.Laws Ann. tit. 31, 5303, the

analogous state tolling statute, required an intervening suit to be the same as the

suit later filed in order for the earlier suit to have a tolling effect.

On the first of the two above questions the duration of the applicable

limitations period the district judge who acted in the present case agreed with

his colleague in Graffals (whom we, in turn, had affirmed) that one year was

the proper limit.1 However, plaintiff-appellee, in urging us to support the

judgment in her favor, argues that under Puerto Rican law a three-year statute

of limitations is appropriate. If so, there would be no need to confront the

troublesome tolling issue, infra. Since it is important to settle the matter and

since the possibility of a three-year statute was not raised in Graffals, see 550

F.2d at 688, we shall explore plaintiff's claim notwithstanding the stare decisis

effect of Graffals.

Federal courts ordinarily look to the period of limitations applicable to the most

closely analogous state cause of action to determine when a 1983 suit is time

barred. Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc.,421 U.S. 454, 95 S.Ct. 1716,

44 L.Ed.2d 295 (1975); O'Sullivan v. Felix,233 U.S. 318, 34 S.Ct. 596, 58

L.Ed. 980 (1914). In Graffals we held that as 1983 suits sound in tort,

P.R.Laws Ann. tit. 31, 5298(2), the general one-year statute of limitations for

tort actions under the law of the Commonwealth, would apply. Plaintiff bases

her argument for a three-year statute upon the fact that Puerto Rico has its own

statute for political discharge of an employee, i. e. P.R.Laws Ann. tit. 29, 136,

which plaintiff contends is the most analogous cause of action to the one she

has brought. Plaintiff further argues that the limitations period for this cause of

action is three years. But even assuming that plaintiff's action were for a

"political" firing, it does not appear that she is correct in claiming that a threeyear limitations period applies. Section 136 sets forth no specific limitations

period, and plaintiff concedes that one must be found in the general provisions

of the Commonwealth's code. The apparent source of the three-year period

claimed by plaintiff is P.R.Laws Ann. tit. 31, 5297(3), which governs "the

payment of mechanics, servants, and laborers the amounts due for their

services, and for the supplies or disbursements they may have incurred with

regard to the same."2 A literal reading of this provision would suggest that it is

meant to cover claims based on contract or quasi-contract, not those grounded

on tortious dismissals. Case law buttresses this interpretation. In Cortes v.

Valdes, 43 P.R.R. 184 (1932), the Supreme Court of Puerto Rico held that the

predecessor of 5298(2), governing suits sounding in the civil law equivalent

of tort, applied to an action for damages caused by an illegal dismissal. This

result confirms the analysis in Graffals v. Garcia, supra, that 1983 actions

based on a violation by a governmental employer of the duty not to discharge an

employee unconstitutionally sound in tort, not contract, id. at 688, and that the

one year statute provided by 5298(2) should apply. The district court was

therefore correct when it made a like assumption in this case.

9

We face a more difficult question when it comes to the tolling issue. Here the

district judge who decided the instant case is at odds with his colleague who

ruled in Graffals. The tolling of the one year period provided by 5298(2) is

governed by P.R.Laws Ann. tit. 31, 5303, which states:

10

"Prescription

of actions is interrupted by their institution before the courts, by

extrajudicial claim of the creditor, and by any act of acknowledgment of the debt by

the debtor."

11

In interpreting the phrase "their institution before the courts," the district judge

in Graffals v. Garcia, supra, ruled "that said action be the one exercised, not

another one that is more or less analogous." 415 F.Supp. at 20 (italics in

original). This court, in approving that holding, noted that the opposing party

did not "seriously quarrel with this conclusion." 550 F.2d at 688.

12

But the district judge here, although aware of our decision in Graffals, was

persuaded to interpret 5303 differently. Believing that the combined common

and civil law system of Puerto Rico requires a more flexible approach than that

of the Spanish Civil Code, the judge held that the institution of any action

between the same parties that constituted a diligent pursuit of the right claimed

in the later action would come within 5303 and would therefore toll the

statute of limitations. The court held, in particular, that an action of mandamus

in the Commonwealth court to gain reinstatement constituted a diligent pursuit

of the constitutional right sought in plaintiff's 1983 suit and accordingly tolled

the statute of limitations.

13

Although as an ordinary matter the interpretation of local law pertaining to a

statute of limitations by the district court sitting in that jurisdiction is entitled to

great deference from a reviewing court, see Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160,

181-82, 96 S.Ct. 2586, 49 L.Ed.2d 415 (1976); Graffals v. Garcia, supra, 550

F.2d at 688, the existence of a sharp conflict among the judges of that district

undercuts this deference and compels an independent assessment of the

question by a court of appeals. In this case, the language of the statute tends to

support the position taken in Graffals: by referring to "their institution", the

statute appears to state that it is the commencement of the action at bar, and not

some other action, which tolls the period of limitation. Conceding the absence

of any Commonwealth judicial authority on the matter one way or the other,

the district judge in Graffals found direct support for his interpretation in an

authoritative commentary on the identical provision in the Spanish Civil Code.

See 12 Manresa, Comentarios al Codigo Civil Espanol 955 (1951 ed.). The

district judge in the case at bar grounded a contrary interpretation on his view

of the structure of the judicial system of Puerto Rico, which commingles

elements of common and civil law. He also cited certain different

commentators on the Spanish Civil Code as supporting, indirectly, a more

liberal interpretation of the tolling provision.

14

To the extent the district court grounded its ruling on its sense of developments

in the common rather than civil law, it is important to note that in the American

common law generally, prior judicial actions do not toll the statute of

limitations, no matter how close their relationship to the one at bar. See, e. g.,

UAW v. Hoosier Cardinal Corp., 383 U.S. 696, 708, 86 S.Ct. 1107, 16 L.Ed.2d

192 (1966); Falsetti v. Local No. 2026, UMW, 355 F.2d 658, 662 & n. 15 (3d

Cir. 1966).3 Federal courts have applied to 1983 suits in particular a rule that

prior actions in the state courts do not toll the applicable state statute of

limitations. Williams v. Walsh, 558 F.2d 667 (2d Cir. 1977); Meyer v. Frank,

550 F.2d 726 (2d Cir.), cert. denied, --- U.S. ----, 98 S.Ct. 112, 54 L.Ed.2d 90

(1977); Ammlung v. City of Chester, 494 F.2d 811 (3d Cir. 1974).4

15

In sum, the rule advanced by the court below not only lacks any direct support

in Commonwealth precedent and conflicts with an earlier district court

interpretation, but is contrary to settled principles prevalent elsewhere in the

United States. Moreover, the more specific Spanish civil law interpretation is

also to the contrary. In light of these factors, we are unwilling to depart from

the interpretation of 5303 announced in Graffals, viz., that to toll the statute,

the action must be the case at bar, and not merely a somewhat related action

arising from the same facts. Because the mandamus action brought by plaintiff

in the Commonwealth courts did not toll the one year statute of limitations, her

claim was time barred and should have been dismissed.

16

Although our determination of the statute of limitations issue is dispositive of

this suit, several rulings of the district court on the merits of plaintiff's due

process claim require comment. The district court grounded its decision that

plaintiff had not received her procedural rights on an assumption that notice and

a hearing were constitutional prerequisites before any adverse personnel action

could be taken against her. Supreme Court precedent and decisions of this

court, however, suggest rather strongly that in employee discharge cases, a

hearing held after the removal of the employee satisfies the due process clause.

Arnett v. Kennedy, 416 U.S. 134, 94 S.Ct. 1633, 40 L.Ed.2d 15 (1974);

Soldevila v. Secretary of Agriculture, 512 F.2d 427 (1st Cir. 1975); cf.

Mathews v. Eldridge, 424 U.S. 319, 96 S.Ct. 893, 47 L.Ed.2d 18 (1976). Where

the only immediate loss is of the tenured nature of the employment, rather than

of the job itself, the need for a prior hearing is even less pressing, as the

employee suffers no immediate loss in compensation or benefits. Looking at

the proceedings in which plaintiff participated after her loss of tenure, the

requirements of due process seemingly were satisfied. The letter she received

on April 13 gave her adequate notice of her loss of tenure and the grounds for

that action,5 and the subsequent Personnel Board proceeding provided an

impartial tribunal that fairly considered the circumstances of the dispute and

interpreted the applicable statutes and regulations according to its own

informed judgment. Although the Board's decision was inconsistent with the

position taken earlier by the Office of Personnel, the Board grounded its

decision on a differing interpretation of the applicable statute that rested on a

fair reading of the language of that provision. In sum, nothing in the record

indicates that plaintiff's due process rights were violated, and the district court's

holding to the contrary rested on a misunderstanding of the applicable

standards.

17

The decision of the district court is reversed.

Of the Second Circuit, sitting by designation

Both judges are permanent members of the district court of Puerto Rico and, of

course, members of the bar of Puerto Rico

The other three-year statute of limitations cited to us, P.R.Laws Ann. tit. 29,

246d, applies only to causes of action under Puerto Rico's minimum wage law

An exception to this rule exists for prior actions that bar the bringing of a

subsequent suit during their pendency. See 54 C.J.S. Limitations of Actions

247. The filing of plaintiff's mandamus suit, however, could not have acted as a

bar to a simultaneous proceeding in federal court. See General Atomic Co. v.

Felter, --- U.S. ----, 98 S.Ct. 76, 54 L.Ed.2d 199 (U.S. Oct. 31, 1977); Donovan

v. City of Dallas, 377 U.S. 408, 84 S.Ct. 1579, 12 L.Ed.2d 409 (1964)

4

One federal court, although conceding that state law did not provide a rule

allowing related actions to toll a 1983 suit, has suggested that federal policies

underlying 1983 might require the fashioning of a federal tolling rule to that

effect. See Mizell v. North Broward Hospital Dist., 427 F.2d 468 (5th Cir.

1970). Subsequent decisions of that circuit have refused to follow Mizell's

dicta, see Blair v. Page Aircraft Maintenance, Inc., 467 F.2d 815 (5th Cir.

1972), and the reasoning underlying those remarks was rejected by the

Supreme Court in Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., 421 U.S. 454, 95

S.Ct. 1716, 44 L.Ed.2d 295 (1975). Every court of appeals that has since

considered the issue has refused to follow Mizell, Meyer v. Frank, supra at 729;

Ammlung v. City of Chester, supra at 816

The district court ruled that the letter gave plaintiff inadequate notice to permit

her to take advantage of the Personnel Board proceeding. It is difficult to

understand the basis for this ruling, unless the district court believed that

something equivalent to a fully reasoned judicial opinion as to plaintiff's rights

and responsibilities was necessary to meet the notice requirement. The letter

indicated that plaintiff had lost her tenure because her service under contract

had been improperly credited toward the mandatory probation period. She was

put on notice that in order to regain her status, she had to demonstrate either that

her position did not require a probationary period or that her prior work under

contract should have been credited toward this period. Nothing more was

required

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Juan Hernandez Del Valle v. Jesus Santa Aponte, Etc., 575 F.2d 321, 1st Cir. (1978)Dokument5 SeitenJuan Hernandez Del Valle v. Jesus Santa Aponte, Etc., 575 F.2d 321, 1st Cir. (1978)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Carolyn N. Hess, Administratrix of The Estate of David Milano, Deceased v. Bob Eddy, 689 F.2d 977, 11th Cir. (1982)Dokument7 SeitenCarolyn N. Hess, Administratrix of The Estate of David Milano, Deceased v. Bob Eddy, 689 F.2d 977, 11th Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States Court of Appeals, First CircuitDokument5 SeitenUnited States Court of Appeals, First CircuitScribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Walden, Iii, Inc. v. State of Rhode Island, 576 F.2d 945, 1st Cir. (1978)Dokument5 SeitenWalden, Iii, Inc. v. State of Rhode Island, 576 F.2d 945, 1st Cir. (1978)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aram K. Berberian v. M. Frank Gibney, 514 F.2d 790, 1st Cir. (1975)Dokument5 SeitenAram K. Berberian v. M. Frank Gibney, 514 F.2d 790, 1st Cir. (1975)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ignacio Gual Morales v. Pedro Hernandez Vega, Etc., 579 F.2d 677, 1st Cir. (1978)Dokument7 SeitenIgnacio Gual Morales v. Pedro Hernandez Vega, Etc., 579 F.2d 677, 1st Cir. (1978)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cain v. Commercial Publishing Co., 232 U.S. 124 (1914)Dokument6 SeitenCain v. Commercial Publishing Co., 232 U.S. 124 (1914)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ignacio Gual Morales v. Pedro Hernandez Vega, 604 F.2d 730, 1st Cir. (1979)Dokument5 SeitenIgnacio Gual Morales v. Pedro Hernandez Vega, 604 F.2d 730, 1st Cir. (1979)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Burnett v. New York Central R. Co., 380 U.S. 424 (1965)Dokument10 SeitenBurnett v. New York Central R. Co., 380 U.S. 424 (1965)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Waterman Steamship Corporation v. Ramon Rodriguez Colon, Ramon Rodriguez Colon v. Waterman Steamship Corporation, 290 F.2d 175, 1st Cir. (1961)Dokument8 SeitenWaterman Steamship Corporation v. Ramon Rodriguez Colon, Ramon Rodriguez Colon v. Waterman Steamship Corporation, 290 F.2d 175, 1st Cir. (1961)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Filed: Patrick FisherDokument3 SeitenFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Judith Beeler, A Minor, by Charles Beeler and Ruth Beeler, Her Parents and Natural Guardians, and Charles Beeler and Ruth Beeler, in Their Own Right v. United States, 338 F.2d 687, 3rd Cir. (1964)Dokument5 SeitenJudith Beeler, A Minor, by Charles Beeler and Ruth Beeler, Her Parents and Natural Guardians, and Charles Beeler and Ruth Beeler, in Their Own Right v. United States, 338 F.2d 687, 3rd Cir. (1964)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- John T. Witherow v. The Firestone Tire & Rubber Company, A Corporation, 530 F.2d 160, 3rd Cir. (1976)Dokument13 SeitenJohn T. Witherow v. The Firestone Tire & Rubber Company, A Corporation, 530 F.2d 160, 3rd Cir. (1976)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Goodwin v. Townsend, 197 F.2d 970, 3rd Cir. (1952)Dokument4 SeitenGoodwin v. Townsend, 197 F.2d 970, 3rd Cir. (1952)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Charles Gomez v. Government of The Virgin Islands, Department of Public Safety & Police Benevolent Association, 882 F.2d 733, 3rd Cir. (1989)Dokument10 SeitenCharles Gomez v. Government of The Virgin Islands, Department of Public Safety & Police Benevolent Association, 882 F.2d 733, 3rd Cir. (1989)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States Court of Appeals Third CircuitDokument4 SeitenUnited States Court of Appeals Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Odell v. Humble Oil & Refining Co, 201 F.2d 123, 10th Cir. (1953)Dokument8 SeitenOdell v. Humble Oil & Refining Co, 201 F.2d 123, 10th Cir. (1953)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Henry Howell v. Cataldi, 464 F.2d 272, 3rd Cir. (1972)Dokument20 SeitenHenry Howell v. Cataldi, 464 F.2d 272, 3rd Cir. (1972)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5 Fair Empl - Prac.cas. 347, 5 Empl. Prac. Dec. P 8403 Abelino Archuleta v. Duffy's Inc., 471 F.2d 33, 10th Cir. (1973)Dokument9 Seiten5 Fair Empl - Prac.cas. 347, 5 Empl. Prac. Dec. P 8403 Abelino Archuleta v. Duffy's Inc., 471 F.2d 33, 10th Cir. (1973)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Georgia Railroad & Banking Co. v. Redwine, 342 U.S. 299 (1952)Dokument6 SeitenGeorgia Railroad & Banking Co. v. Redwine, 342 U.S. 299 (1952)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Crowder v. Whalen, 10th Cir. (1998)Dokument8 SeitenCrowder v. Whalen, 10th Cir. (1998)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Margaret Marshall v. George J. Mulrenin, 508 F.2d 39, 1st Cir. (1974)Dokument8 SeitenMargaret Marshall v. George J. Mulrenin, 508 F.2d 39, 1st Cir. (1974)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pedro Berrios v. Department of The Army, 884 F.2d 28, 1st Cir. (1989)Dokument8 SeitenPedro Berrios v. Department of The Army, 884 F.2d 28, 1st Cir. (1989)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pulliam v. Allen, 466 U.S. 522 (1984)Dokument30 SeitenPulliam v. Allen, 466 U.S. 522 (1984)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brown v. Dunbar & Sullivan Dredging Co, 189 F.2d 871, 2d Cir. (1951)Dokument6 SeitenBrown v. Dunbar & Sullivan Dredging Co, 189 F.2d 871, 2d Cir. (1951)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- New Mexico Citizens For Clean Air and Water Pueblo of San Juan v. Espanola Mercantile Company, Inc., Doing Business As Espanola Transit Mix Co., 72 F.3d 830, 10th Cir. (1996)Dokument8 SeitenNew Mexico Citizens For Clean Air and Water Pueblo of San Juan v. Espanola Mercantile Company, Inc., Doing Business As Espanola Transit Mix Co., 72 F.3d 830, 10th Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Pauline Caldwell Appeal of Audrey Brickley, 463 F.2d 590, 3rd Cir. (1972)Dokument6 SeitenUnited States v. Pauline Caldwell Appeal of Audrey Brickley, 463 F.2d 590, 3rd Cir. (1972)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Filed: Patrick FisherDokument5 SeitenFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transcontinental & Western Air, Inc. v. Koppal, 345 U.S. 653 (1953)Dokument7 SeitenTranscontinental & Western Air, Inc. v. Koppal, 345 U.S. 653 (1953)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Walker v. City of Fort Morgan, 145 F.3d 1347, 10th Cir. (1998)Dokument6 SeitenWalker v. City of Fort Morgan, 145 F.3d 1347, 10th Cir. (1998)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Francis I. Redman v. A. Frances Warrener, Etc., Francis I. Redman v. A. Frances Warrener, Etc., 516 F.2d 766, 1st Cir. (1975)Dokument4 SeitenFrancis I. Redman v. A. Frances Warrener, Etc., Francis I. Redman v. A. Frances Warrener, Etc., 516 F.2d 766, 1st Cir. (1975)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- New York Ex Rel. Bryant v. Zimmerman, 278 U.S. 63 (1928)Dokument17 SeitenNew York Ex Rel. Bryant v. Zimmerman, 278 U.S. 63 (1928)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scheuer v. Rhodes, 416 U.S. 232 (1974)Dokument14 SeitenScheuer v. Rhodes, 416 U.S. 232 (1974)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- El Paso & Northeastern R. Co. v. Gutierrez, 215 U.S. 87 (1909)Dokument7 SeitenEl Paso & Northeastern R. Co. v. Gutierrez, 215 U.S. 87 (1909)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. A & P Arora, LTD., and Ajay Arora, 46 F.3d 1152, 10th Cir. (1995)Dokument4 SeitenUnited States v. A & P Arora, LTD., and Ajay Arora, 46 F.3d 1152, 10th Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Greschner v. Cooksey, 10th Cir. (2006)Dokument6 SeitenGreschner v. Cooksey, 10th Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Elliott Sharapan, Victor Sharapan, 13 F.3d 781, 3rd Cir. (1994)Dokument8 SeitenUnited States v. Elliott Sharapan, Victor Sharapan, 13 F.3d 781, 3rd Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Selover, Bates & Co. v. Walsh, 226 U.S. 112 (1912)Dokument5 SeitenSelover, Bates & Co. v. Walsh, 226 U.S. 112 (1912)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hernandez v. Denver Post, 10th Cir. (1999)Dokument8 SeitenHernandez v. Denver Post, 10th Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ramonita Ortiz v. United States Government v. Hospital Mimiya, Inc., Third-Party, 595 F.2d 65, 1st Cir. (1979)Dokument13 SeitenRamonita Ortiz v. United States Government v. Hospital Mimiya, Inc., Third-Party, 595 F.2d 65, 1st Cir. (1979)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lawrence W. Larsen v. American Airlines, Inc., 313 F.2d 599, 2d Cir. (1963)Dokument7 SeitenLawrence W. Larsen v. American Airlines, Inc., 313 F.2d 599, 2d Cir. (1963)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ellis B. Grady, JR., Administrator, C.T.A., of Margarette W. Rodgers, Deceased v. Richard Eugene Irvine, 254 F.2d 224, 4th Cir. (1958)Dokument5 SeitenEllis B. Grady, JR., Administrator, C.T.A., of Margarette W. Rodgers, Deceased v. Richard Eugene Irvine, 254 F.2d 224, 4th Cir. (1958)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 39 Fair Empl - Prac.cas. 1750, 39 Empl. Prac. Dec. P 35,876 Harry L. Dillman v. Combustion Engineering, Inc., 784 F.2d 57, 2d Cir. (1986)Dokument7 Seiten39 Fair Empl - Prac.cas. 1750, 39 Empl. Prac. Dec. P 35,876 Harry L. Dillman v. Combustion Engineering, Inc., 784 F.2d 57, 2d Cir. (1986)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States Court of Appeals: For The First CircuitDokument18 SeitenUnited States Court of Appeals: For The First CircuitScribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Filed: Patrick FisherDokument9 SeitenFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Charles Ortiz, 733 F.2d 1416, 10th Cir. (1984)Dokument4 SeitenUnited States v. Charles Ortiz, 733 F.2d 1416, 10th Cir. (1984)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Larkins Vs NLRC DigestedDokument2 SeitenLarkins Vs NLRC DigestedGretel R. Madanguit100% (1)

- Tyler v. Judges of Court of Registration, 179 U.S. 405 (1900)Dokument9 SeitenTyler v. Judges of Court of Registration, 179 U.S. 405 (1900)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Helen Mascuilli, Administratrix of The Estate of Albert Mascuilli, Deceased v. United States, 411 F.2d 867, 3rd Cir. (1969)Dokument9 SeitenHelen Mascuilli, Administratrix of The Estate of Albert Mascuilli, Deceased v. United States, 411 F.2d 867, 3rd Cir. (1969)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Neil T. Mulrain v. Board of Selectmen of The Town of Leicester, 944 F.2d 23, 1st Cir. (1991)Dokument5 SeitenNeil T. Mulrain v. Board of Selectmen of The Town of Leicester, 944 F.2d 23, 1st Cir. (1991)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 769 F.2d 160 119 L.R.R.M. (BNA) 2061Dokument7 Seiten769 F.2d 160 119 L.R.R.M. (BNA) 2061Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- No. 81-1928, 678 F.2d 453, 3rd Cir. (1982)Dokument13 SeitenNo. 81-1928, 678 F.2d 453, 3rd Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Walker v. Crosby, 341 F.3d 1240, 11th Cir. (2003)Dokument10 SeitenWalker v. Crosby, 341 F.3d 1240, 11th Cir. (2003)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Not PrecedentialDokument9 SeitenNot PrecedentialScribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jerome A. Crowder V., 133 F.3d 932, 10th Cir. (1998)Dokument5 SeitenJerome A. Crowder V., 133 F.3d 932, 10th Cir. (1998)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rebecca Maycher v. Muskogee Medical Center Auxiliary, A Nonprofit Corporation, 129 F.3d 131, 10th Cir. (1997)Dokument5 SeitenRebecca Maycher v. Muskogee Medical Center Auxiliary, A Nonprofit Corporation, 129 F.3d 131, 10th Cir. (1997)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Edward Broughton v. Russell A. Courtney, Donald A. D'Lugos, 861 F.2d 639, 11th Cir. (1988)Dokument8 SeitenEdward Broughton v. Russell A. Courtney, Donald A. D'Lugos, 861 F.2d 639, 11th Cir. (1988)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Inexplicable Deception: A State Corruption of JusticeVon EverandAn Inexplicable Deception: A State Corruption of JusticeNoch keine Bewertungen

- California Supreme Court Petition: S173448 – Denied Without OpinionVon EverandCalifornia Supreme Court Petition: S173448 – Denied Without OpinionBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1)

- The Book of Writs - With Sample Writs of Quo Warranto, Habeas Corpus, Mandamus, Certiorari, and ProhibitionVon EverandThe Book of Writs - With Sample Writs of Quo Warranto, Habeas Corpus, Mandamus, Certiorari, and ProhibitionBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (9)

- Coyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument7 SeitenCoyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument4 SeitenUnited States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument9 SeitenUnited States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Pecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument25 SeitenPecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Apodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument15 SeitenApodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument20 SeitenUnited States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- City of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument21 SeitenCity of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDokument14 SeitenPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Consolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument22 SeitenConsolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDokument24 SeitenPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument5 SeitenUnited States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument50 SeitenUnited States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Harte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument100 SeitenHarte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDokument10 SeitenPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument27 SeitenUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- NM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument9 SeitenNM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument2 SeitenUnited States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument25 SeitenUnited States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument7 SeitenUnited States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument15 SeitenUnited States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Northern New Mexicans v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument10 SeitenNorthern New Mexicans v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument25 SeitenUnited States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chevron Mining v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument42 SeitenChevron Mining v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument5 SeitenPledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Robles v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument5 SeitenRobles v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jimenez v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument5 SeitenJimenez v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument4 SeitenUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDokument17 SeitenPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coburn v. Wilkinson, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument9 SeitenCoburn v. Wilkinson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Parker Excavating v. LaFarge West, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument24 SeitenParker Excavating v. LaFarge West, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strategic Litigation Impacts, Insight From Global ExperienceDokument144 SeitenStrategic Litigation Impacts, Insight From Global ExperienceDhanil Al-GhifaryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Board of Commissioners V Dela RosaDokument4 SeitenBoard of Commissioners V Dela RosaAnonymous AUdGvY100% (2)

- Quality Manual.4Dokument53 SeitenQuality Manual.4dcol13100% (1)

- Information For MT101Dokument9 SeitenInformation For MT101SathyanarayanaRaoRNoch keine Bewertungen

- Parking Tariff For CMRL Metro StationsDokument4 SeitenParking Tariff For CMRL Metro StationsVijay KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Warehouse Receipt Law ReviewerDokument6 SeitenWarehouse Receipt Law ReviewerElaine Villafuerte Achay100% (6)

- Chinese OCW Conversational Chinese WorkbookDokument283 SeitenChinese OCW Conversational Chinese Workbookhnikol3945Noch keine Bewertungen

- Owner Contractor AgreementDokument18 SeitenOwner Contractor AgreementJayteeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sinif Matemati̇k Eşli̇k Ve Benzerli̇k Test PDF 2Dokument1 SeiteSinif Matemati̇k Eşli̇k Ve Benzerli̇k Test PDF 2zboroglu07Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2020-10-22 CrimFilingsMonthly - WithheadingsDokument579 Seiten2020-10-22 CrimFilingsMonthly - WithheadingsBR KNoch keine Bewertungen

- Solved Problems in Compound InterestDokument3 SeitenSolved Problems in Compound Interestjaine ylevreb100% (1)

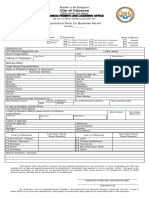

- Application Form For Business Permit 2016Dokument1 SeiteApplication Form For Business Permit 2016Monster EngNoch keine Bewertungen

- 101, Shubham Residency, Padmanagar PH ., Hyderabad GSTIN:36AAFCV7646D1Z5 GSTIN/UIN: 36AAFCV7646D1Z5 State Name:, Code: Contact: 9502691234,9930135041Dokument8 Seiten101, Shubham Residency, Padmanagar PH ., Hyderabad GSTIN:36AAFCV7646D1Z5 GSTIN/UIN: 36AAFCV7646D1Z5 State Name:, Code: Contact: 9502691234,9930135041mrcopy xeroxNoch keine Bewertungen

- Friday Foreclosure List For Pierce County, Washington Including Tacoma, Gig Harbor, Puyallup, Bank Owned Homes For SaleDokument11 SeitenFriday Foreclosure List For Pierce County, Washington Including Tacoma, Gig Harbor, Puyallup, Bank Owned Homes For SaleTom TuttleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Biden PollDokument33 SeitenBiden PollNew York PostNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clerkship HandbookDokument183 SeitenClerkship Handbooksanddman76Noch keine Bewertungen

- Google Hacking CardingDokument114 SeitenGoogle Hacking CardingrizkibeleraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Midf FormDokument3 SeitenMidf FormRijal Abd ShukorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fourth Commandment 41512Dokument11 SeitenFourth Commandment 41512Monica GodoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Economy of VeitnamDokument17 SeitenEconomy of VeitnamPriyanshi LohaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Is 14394 1996 PDFDokument10 SeitenIs 14394 1996 PDFSantosh KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- WCL8 (Assembly)Dokument1 SeiteWCL8 (Assembly)Md.Bellal HossainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Entrant Status Check Web SiteDokument1 SeiteEntrant Status Check Web SitetoukoalexandraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Important Notice For Passengers Travelling To and From IndiaDokument3 SeitenImportant Notice For Passengers Travelling To and From IndiaGokul RajNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aetna V WolfDokument2 SeitenAetna V WolfJakob EmersonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Project WBS DronetechDokument1 SeiteProject WBS DronetechFunny Huh100% (2)

- CESSWI BROCHURE (September 2020)Dokument2 SeitenCESSWI BROCHURE (September 2020)Ahmad MensaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Last Hacker: He Called Himself Dark Dante. His Compulsion Led Him To Secret Files And, Eventually, The Bar of JusticeDokument16 SeitenThe Last Hacker: He Called Himself Dark Dante. His Compulsion Led Him To Secret Files And, Eventually, The Bar of JusticeRomulo Rosario MarquezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lords Day Celebration BookletDokument9 SeitenLords Day Celebration BookletOrlando Palompon100% (2)

- MCQ On Guidance Note CARODokument63 SeitenMCQ On Guidance Note CAROUma Suryanarayanan100% (1)