Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

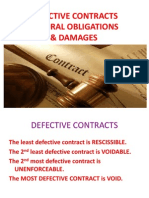

Defective Contracts

Hochgeladen von

Roselle CasiguranOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Defective Contracts

Hochgeladen von

Roselle CasiguranCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

CHAPTER 6 RESCISSIBLE CONTRACTS

1. 2. 3. 4.

4 Classes of defective contracts: Rescissible contracts which is a contract that has caused a particular damage to one of the parties or to a 3 rd person and which for equitable reasons may be set aside even if it is valid. Voidable contracts which is a contract in which the consent of one party is defective, either because of want of capacity or because it is vitiated, but which contract is valid until set aside by the competent court. Unenforceable Contracts which is a contract that for some reason cannot be enforced, unless it is ratified in the manner provided by law Void or Inexistent Contracts which is an absolute nullity and produces no effect, as if it had never been executed or entered into. As to defect: As to effect: Considered valid and enforceable until they are rescinded by a competent court Considered valid and enforceable until they are annulled by a competent court Cannot be enforced by a proper action in court As to prescriptibility of action or defense: The action for rescission may prescribe As to susceptibility of ratification: Not susceptible ratification of As to who may assail contracts May be assailed not only by a contracting party but even by a 3rd person who is prejudiced or damaged by the contract Can be assailed only by a contracting party As to how contracts may be assailed May be assailed directly only, and not collaterally

RESCISSIBLE

There is damage or injury either to one of the contracting parties or to third persons. There is vitiation of consent or legal incapacity of one of the contracting parties. The contract is entered into in excess or without any authority, or does not comply with the Statute of Frauds, or both contracting parties are legally incapacitated One or more of the essential requisites of a valid contract are lacking either in fact or law

VOIDABLE

UNENFORCEABL E

VOID OR INEXISTENT

As a general rule, do not produce any legal effect

The action for annulment or the defense of annulability may prescribe. The corresponding action for recovery, if there was total or partial performance of the unenforceable contract under No. 1 or No. 3 of Art. 1403, may prescribe The action for declaration of nullity or inexistence or the defense of nullity or inexistence does not prescribed

Susceptible

May be assailed directly or collaterally

Susceptible

May be assailed only by a contracting party

May be assailed directly or collaterally

Not susceptible

May be assailed not only by a contracting party but even by a 3rd person whose interest is directly affected

May be assailed directly or collaterally

Art. 1380. Contracts validly agreed upon may be rescinded in the cases established by law. (1290)

Rescissible Contracts all of the essential requisites of a contract exist and the contract is valid, but by reason of injury or damage to either of the contracting parties or to 3rd persons, such as creditors, it may be rescinded. Rescissible C. a contract with is valid because it contains all of the essential requisites prescribed by law, but which is defective because of injury or damage to either of the contracting parties or to 3rd persons, as a consequence of which it may be rescinded by means of a proper action for rescission. TOLENTINO: Relatively Ineffective Contract is distinguished from the voidable contract in that its ineffectiveness, with respect to the party concerned, is produced ipso jure, while a voidable contract does not become inoperative unless an action to annul it is instituted and allowed. It differs from the void or inexistent contract, in that the ineffectiveness of the latter is absolute, because it cannot be ratified, while the relatively ineffective contract can be made completely effective by the consent of the person as to whom it is ineffective, or by the cessation of the impediment which prevents its complete effectiveness. Characteristics: Their defect constitutes in injury or damage either to one of the contracting parties or to 3rd persons Before rescission, they are valid and therefore, legally effective They can be attacked directly only, and not collaterally They can be attacked only either by a contracting party or by a 3rd person who is injured or defrauded They are susceptible of convalidation only by prescription and not by ratification TOLENTINO: Requisites of Rescission: The contract must be a rescissible contract, such as those mentioned in Art. 1381 and 1382 The party asking for rescission must have no other legal means to obtain reparation for the damages suffered by him The person demanding rescission must be able to return whatever he may be obliged to restore if rescission is granted The things which are the object of the contract must not have passed legally to the possession of a 3rd person acting in good faith The action for rescission must be brought within the prescriptive period of 4 years.

1.

2. 3.

4.

5.

1. 2. 3.

4.

5.

Remission a remedy granted by law to the contracting parties, and even to 3 rd persons, to secure the reparation of damages caused to them by a contract, even if the same should be valid, by means of the restoration of things to their condition prior to the celebration of the contract. Rescission distinguished from resolution of reciprocal obligations under Art. 1191 of the Code similarities both with respect to validity and effects Rescission As to party who may institute action: As to causes: As to power of the courts: The action may be instituted not only by a party to the contract but even a 3rd person There are several causes or grounds such as lesion, fraud and others expressly specified by law In rescission there is no power of the courts to grant an extension of time for performance of the obligation so long as there is a ground for rescission In rescission any contract, whether unilateral or reciprocal, may be rescinded Resolution The action may be instituted only by a party to the contract The only ground is failure of one of the parties to comply with what is incumbent upon him In resolution the law expressly declares that courts shall have a discretionary power to grant an extension for performance provided that there is a just cause Only reciprocal contracts may be resolved

As to contract which may be rescinded or resolved:

Neither must rescission be confused with rescission of a contract by mutual consent of the contracting parties Rescission by mutual consent is simply another contract for the dissolution of a previous one, and its effects, in relation to the contract so dissolved, should be determined by the agreement made by the parties, or by the application of other legal provisions, but not by Articles 1385, which is not applicable.

Art. 1381. The following contracts are rescissible: (1) Those which are entered into by guardians whenever the wards whom they represent suffer lesion by more than one-fourth of the value of the things which are the object thereof; (2) Those agreed upon in representation of absentees, if the latter suffer the lesion stated in the preceding number; (3) Those undertaken in fraud of creditors when the latter cannot in any other manner collect the claims due them; (4) Those which refer to things under litigation if they have been entered into by the defendant without the knowledge and approval of the litigants or of competent judicial authority; (5) All other contracts specially declared by law to be subject to rescission. (1291a)

Art. 1382. Payments made in a state of insolvency for obligations to whose fulfillment the debtor could not be compelled at the time they were effected, are also rescissible. (1292)

TOLENTINO: A valid contract can be rescinded only for legal cause. The first of the rescissible contracts are those which are entered into by guardians. This is without prejudice to the provision of Art. 1386 which states that rescission shall not take place with respect to contracts approved by the courts. Under the Rules of Court, a judicial guardian entering into a contract with respect to the property of his ward must ordinarily secure the approval of a competent court Also in case of a father or mother considered as a natural guardian of the property of a child under parental authority where such property is worth more than P2000. Contract involves the sale or encumbrance of real property, judicial approval is indispensable. Consequently, if a guardian sells, mortgages or otherwise encumbers real property belonging to his war without judicial approval, the contract is unenforceable, and not rescissible even if the latter suffers lesion or damage of more than onefourth of the value of the property. However, if he enters into a contract falling within the scope of his powers as guardian of the person and property, or only of the property, of his ward, such as when the contract involves acts of administration, express judicial approval is not necessary, in which case the contract is rescissible if the latter suffers the lesion or damage mentioned in No. 1 of Art. 1381 of the Code The second is contracts in behalf of Absentees However, such contracts are not rescissible if they have been approved by the courts Same as those of the guardians, the principles enunciated in the preceding section are also applicable here. TOLENTINO: A guardian is authorized only to manage the estate of his ward; hence, he has no power to dispose of any portion thereof without approval of the court. Requisites for contracts entered into by guardians in behalf of his ward or by a legal representative in behalf of an absentee: The contract must have been entered into by a guardian in behalf of his ward or by a legal representative in behalf of an absentee. The ward or absentee must have suffered lesion of more than one-fourth of the value of the property which is the object of the contract The contract must have been entered into without judicial approval There must be no other legal means for obtaining reparation for the lesion The person bringing the action must be able to return whatever he may be obliged to restore, and The object of the contract must not be legally in the possession of a 3rd person who did not act in bad faith If the object of the contract is legally in the possession of a 3 rd person who did not act in bad faith, the remedy available to the person suffering the lesion is indemnification for damages and not rescission The third is contracts in fraud of creditors this complements Art. 1177 of the Code which states that one of the remedies available to the creditor after he has exhausted all the property in possession of the debtor is to impugn the acts which the latter may have done to defraud him. TOLENTINO: Test of Fraud In determining whether or not a certain conveyance is fraudulent, the question in every case is whether the conveyance was a bona fide transaction or a trick and contrivance to defeat creditors, or whether it conserves to the debtor a special right. TOLENTINO: Signs of Fraud: The fact that the consideration of the conveyance is inadequate A transfer made by a debtor after suit has been begun and while it is pending against him A sale upon credit by an insolvent debtor Evidence pf large indebtedness or complete insolvency The transfer of all or nearly all of his property by a debtor, especially when he is insolvent or greatly embarrassed financially The fact that the transfer is made between father and son, when there are present any of the above circumstances The failure of the vendee to take exclusive possession of all the property Requisites before a contract can be rescinded on the ground that it has been entered into in fraud of creditors: There must be a credit existing prior to the celebration of the contract There must be a fraud, or at least, the intent to commit fraud, or at least, the intent to commit fraud to the prejudice of the creditor seeking the rescission. The creditor cannot in any other legal manner collect his credit The object of the contract must not be legally in the possession of a 3rd person who did not act in bad faith If the object of the contract is legally in the possession of a 3 rd person who did not act in bad faith, the remedy available to the creditor is to proceed against the person causing the loss for damages. The fourth is contracts referring to things under litigation The case contemplated in this number is different from that contemplated in the preceding number. Here the purpose is to secure the possible effectivity of a claim, while in the preceding number the purpose is to guarantee an existing credit; here there is a real right involved, while in the

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

6.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 1.

2.

3.

4.

preceding number there is a personal right, both of which deserve the protection of the law. They are similar in the sense that in both cases the person who can avail of the remedy of rescission is a stranger to the contract

1. 2.

Contracts by insolvent under Art. 1382 In order that the payment can be rescinded, it is indispensable: That it must have been made in a state of insolvency That the obligation must have been one which the debtor could not be compelled to pay at the time such payment was effected. It is clear that the basis of the rescissible character of the transaction is fraud as in the case of No. 3 and 4 of Art. 1381 Insolvency it refers to the financial situation of the debtor by virtue of which is is impossible for him to fulfill his obligations. A judicial declaration of insolvency is not, therefore, necessary. According to Manresa, the obligations contemplated by this article comprehend not only those with a term or which are subject to a suspensive condition, but even void and natural obligations as well as those which are condoned or which have prescribed. EX. Suspensive condition let us assume that A is indebted to B for P10,000 and to C for P5,000. The obligation in favor of C is subject to a suspensive condition. While in a state of insolvency, A pays his obligation to C before the expiration of the term or period. Can B rescind the payment? Under art. 1382, there is no question that the payment is rescissible, but then this conclusion would be in direct conflict with the provision of No. 1 of Art. 1198 of the Code under which A can be compelled by C to pay the obligation even before the expiration of the stipulated term or period since by his insolvency he has already lost his right to the benefit of such term or period. According to Manresa, however, the conflict can easily be resolved by considering the priority of dates between the two debts. If the obligation with a period became due before the obligation to the creditor seeking the rescission became due, then the latter cannot rescind the payment even if such payment was effected before the expiration of the period; but if the obligation with a period became due after the obligation to the creditor seeking the rescission became due, then the latter can rescind the payment. TOLENTINO: Lesion is the injury which one of the parties suffers by virtue of a contract which is disadvantageous to him. Absolute Simulation There is no alienation but a mere pretense that one has been made By all creditors, before or after the simulation Not required Does not seek to set aside the simulated contract, but merely declare its inexistence

TOLENTINO: Accion Pauliana vs. Simulation Accion Pauliana There is real alienation, but it is fraudulent

Can be alleged only by the creditors prior to the act Impossibility of satisfying the plaintiffs claim is required An action to set aside a valid contract

1. 2.

TOLENTINO: Rescission is a subsidiary action, which presupposes that the creditor has exhausted the property of the debtor, which is impossible on credits which cannot be enforced because of the term or condition. TOLENTINO: There are parties who may appear to have become creditors after the alienation, but who may be considered as having a prior right and entitled to the accion pauliana: Those whose claims were acknowledged by the debtor after the alienation, but the origin of which antedated the alienation; the recognition does not give rise to the credit, but merely confirms its existence. For instance, claims for damages arising before the alienation, but acknowledged by the debtor only after the alienation Those who becomes subrogated, before the alienation, in the rights of creditors whose credit were prior to the alienation Other rescissible contracts Arts. 1098, 1189, 1526, 1534, 1539, 1542, 1556, 1560, 1567, and 1659 of the Code

Art. 1383. The action for rescission is subsidiary; it cannot be instituted except when the party suffering damage has no other legal means to obtain reparation for the same. (1294) 1. 2. Before a party who is prejudiced can avail himself of this remedy, it is essential that he has exhausted all of the other legal means to obtain reparation If it can be established that the property which is alienated or transferred by the debtor to another was his only property at the time of the transaction, an action for rescission can certainly be maintained because it is clear that in such case the creditor can have no other remedy. Parties who may institute action: The person who is prejudiced, such as the party suffering the lesion in rescissory actions on the ground of lesion, the creditor who is defrauded in rescissory action on the ground of fraud, and other persons authorized to exercise the same in other rescissory actions. Their representatives

3. 4.

Their heirs (a right to the legitime is similar to a credit of a creditor) he may do so as a representative of the person who suffers from lesion or of the creditor who is defrauded. However, if it can be established that the decedent entered into a contract with another in order to defraud him of his legitime, he has no right to institute the action. Their creditors by virtue of the subrogatory action defined in Art. 1177 of the Code

Art. 1384. Rescission shall be only to the extent necessary to cover the damages caused. (n)

The purpose of rescission is reparation for the damage or injury which is suffered either by a party to the contract or by a 3rd person. Rescission need not be total in character, it may also be partial.

Art. 1385. Rescission creates the obligation to return the things which were the object of the contract, together with their fruits, and the price with its interest; consequently, it can be carried out only when he who demands rescission can return whatever he may be obliged to restore. --- rescissory action on the ground of lesion Neither shall rescission take place when the things which are the object of the contract are legally in the possession of third persons who did not act in bad faith. In this case, indemnity for damages may be demanded from the person causing the loss. (1295) The first paragraph is applicable only to rescissory actions on the ground of lesion and not to rescissory actions on the ground of fraud. This is so because in the latter there can certainly be no obligation on the part of the plaintiff-creditor to restore anything since he has not received anything. Rescission is not possible, unless he who demands it can return whatever he may be obliged to restore. i.e. where a guardian alienates the properties of a minor for P85,000 to a certain person, and subsequently, the minor upon reaching the age of majority, brings an action for the rescission of the contract on the ground of lesion, the effect if rescission is granted would be the restoration of things to their condition prior to the celebration of the contract. But if the plaintiff cannot refund the amount including interest, the action will certainly fail because positive statutory law, no less than uniform court decisions, require, as a condition precedent to rescission, that the consideration received should be refunded. Fruits of the thing refer not only to natural, industrial and civil fruits but also to other accessions obtained by the thing, while interest refers to legal interest. It must be observed that as far as the obligation to restore the fruits is concerned, the rules on possession shall be applied. The determination of the good or bad faith of the party obliged to restore is of transcendental importance in order to assess the fruits or the value thereof which must be returned as well as the expenses which must be reimbursed. i.e. as a condition to the rescission of a contract of sale of a parcel of land, the vendor must refund the vendees (who are in good faith) an amount equal to the purchase price, plus the sum expanded by them in improving the land. The second paragraph this applies to all kinds of rescissible contracts. 2 requisites in order that the acquisition of the thing which consitutues the object of the contract by a 3 rd person shall defeat an action for rescission: That the thing must be legally in the possession of the 3rd person That such person must not have acted in bad faith. If the thing is movable, the concurrence of these requisites offer no difficulty because of the principle that possession of movable property acquired in good faith is equivalent to a title. If the thing is immovable, the right of the 3rd person must be registered or recorded in the proper registry before we can say that the thing is legally in his possession or what amounts to the same thing, before he is protected by law. A 3rd person to whom the realty has been transferred who has not registered his right in the proper registry cannot be protected against the effects of a judgment rendered in the action for rescission. However, where he has registered his right over the realty under the Land Registration Act, there would be no legal obstacles to the transfer of the title of the said property, and for this reason the said transfer cannot be rescinded. The impossibility of maintaining an action for the rescission of the contract where the object is legally in the possession of a 3rd person in good faith, the person who is prejudiced is not left without any remedy. He may still bring an action for indemnity for damages against the person who caused the loss.

1.

2.

Art. 1386. Rescission referred to in Nos. 1 and 2 of Article 1381 shall not take place with respect to contracts approved by the courts. (1296a) Art. 1387. All contracts by virtue of which the debtor alienates property by gratuitous title are presumed to have been entered into in fraud of creditors, when the donor did not reserve sufficient property to pay all debts contracted before the donation. Alienations by onerous title are also presumed fraudulent when made by persons against whom some judgment has been issued. The decision or attachment need not refer to the property alienated, and need not have been obtained by the party seeking the rescission. In addition to these presumptions, the design to defraud creditors may be proved in any other manner recognized by the law of evidence. (1297a)

Art. 1388. Whoever acquires in bad faith the things alienated in fraud of creditors, shall indemnify the latter for damages suffered by them on account of the alienation, whenever, due to any cause, it should be impossible for him to return them. If there are two or more alienations, the first acquirer shall be liable first, and so on successively. (1298a)

1. 2.

Proof of Fraud fraud or intent to defraud may be either presumed in accordance with Art. 1387 of the Code or duly proved in accordance with the ordinary rules of evidence. Presumption of Fraud (fraud of creditors in the following cases): Alienations of property by gratuitous title if the debtor has not reserved sufficient property to pay all of his debts contracted before such alienations. Alienations of property by onerous title if made by a debtor against whom some judgment has been rendered in any instance or some writ of attachment has been issued. The decision or attachment need not refer to the property alienated and need not have been obtained by the party seeking the rescission. Thus, where the debtor alienated a certain property, which was his only attachable property, to his son after judgment had been rendered against him and a writ of execution had been issued, there is presumption that such alienation is fraudulent in accordance with the rule stated in the 2nd paragraph of Art. 1387. This presumption becomes stronger when it is established that the conveyance by the judgment debtor is for the purpose of preventing the judgment creditor or other creditors from seizing the property. But where no judgment or preliminary attachment exists against the debtor, the presumption is not applicable. It must be observed that the above presumptions are disputable, and therefore may be rebutted by satisfactory and convincing evidence to the contrary. Thus, if it can be established that the transferee acquired the property in good faith, without the least intention of impairing the judgment obtained by the creditor against the transferor, and that he paid the purchase price in the belief that the latter could freely dispose of the said property, the presumption of fraud is overthrown. It is not indispensable that the creditor shall have to depend upon the two presumptions established in the 1st and 2nd paragraphs of Art. 1387 in order to prove the existence of fraud or the intention to defraud According to the 3rd paragraph of the same article, the design to defraud creditors may be proved in any other manner recognized by the law of evidence. Thus, in determining whether or not a certain conveyance is fraudulent the question in every case is whether the conveyance was a bona fide transaction or merely a trick or contrivance to defeat creditors. It is not sufficient that it is founded on a good or valuable cause or consideration or is made with bona fide intent: it must have both elements. If defective in either of these particulars, although good between the parties, it is rescissible as far as the creditors are concerned. The test as to whether or not a conveyance is fraudulent is does it prejudice the rights of creditors? In the consideration of whether or not certain transfers or conveyances are fraudulent, the following circumstances have been denominated by the courts as badges of fraud. The fact that the cause or consideration of the conveyance is inadequate. A transfer made by a debtor after suit has been begun and while it is pending against him A sale on credit by an insolvent debtor Evidence of large indebtedness or complete insolvency The transfer of all or nearly all of his property by a debtor, especially when he is insolvent or greatly embarrassed financially The fact that the transfer is made between father and son, when there are present others of the above circumstances The failure of the vendee to take exclusive possession of all the property

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7.

i.e. where it is proved that a certain corporation, which is heavily indebted to a certain bank, sold a large tract of land worth P400,000 to the vendee for only P36,000 in spite of the fact that at the time of such sale it did not have any liquidated assets and that all of its other assets were pledged or mortgaged, some of which were for far more than their actual value, such circumstances would be sufficient to establish the fraudulent character of the conveyance. Consequently, the sale can be set aside by means of an action for rescission at the instance of the creditor. But where the sale is founded on a fictitious cause or consideration it would be futile for such creditor to invoke its rescission since such action presupposes the existence of a valid, not inexistent, to contract. The remedy of the creditor in such case would be to ask for a declaration of nullity of the conveyance. The mere fact of relationship between vendor and vendee, as when the vendor is the vendees mother, is not in itself an element of fraud, if the sale was made for a valuable consideration and said vendor was not at the time of the conveyance insolvent.

The test as to whether or not a conveyance is fraudulent is to determine whether or not it is prejudicial to the rights of the creditors, nevertheless, it is also true that such a test would not be applicable if the conveyance is made in good faith or with a bona fide intent and for a valuable cause or consideration. If the property is acquired by a purchaser in good faith and for value, the acquisition as far as the law is concerned is not fraudulent. The contract or conveyance is not rescissible

If the acquisition by the 3rd person in bad faith the contract or conveyance is rescissible. In such case the creditor who is prejudiced can still proceed after the property. However, if for any cause or reason, it should be

impossible for the acquirer in bad faith to return the property, he shall indemnify the creditor seeking the rescission for damages suffered on account of the alienation. If it happens that there are two or more alienations, the first acquirer shall be liable first, and so on successively,

i.e. If A, against whom a judgment for the payment of a certain debt in favor of X has been rendered, conveys his only property to B in fraud of X, and B, who is aware of the fraud, in turn, conveys to the property to C, and the latter, who is also aware of the fraud, also conveys the property to D, who is a purchaser in good faith and for value, although the conveyance to D cannot be rescinded, yet X can still proceed against B for damages suffered by him on account of the fraudulent alienation, and if he fails to recover he can still proceed against C. It must be noted that if the reason for the impossibility of returning the property acquired in bad faith is a fortuitous event, then under the principle announced in Art. 1174 of the Code, there can be no liability of the acquirer. Art. 1389. The action to claim rescission must be commenced within four years. For persons under guardianship and for absentees, the period of four years shall not begin until the termination of the former's incapacity, or until the domicile of the latter is known. (1299)

TOLENTINO: A minor who is a party to a contract of sale must bring the action for rescission within 4 years after attaining the age of majority, because under the present article the claim of rescission prescribes in 4 years from removal of ones incapacity Under no. 3 and 4 under Art. 1382, it must be counted from the time of the discovery of the fraud. In certain cases of contracts of sale which are specially declared by law to be rescissible, however, the prescriptive period for the commencement of the action is six months or even forty days, counted from the day of delivery. CHAPTER 7 VOIDABLE CONTRACTS

Voidable Contracts may be defined as those where in which all of the essential elements for validity are present, although the element of consent is vitiated either by lack of legal capacity of one of the contracting parties, or by mistake, violence, intimidation, undue influence, or fraud. TOLENTINO: Voidable or annullable contracts are existent, valid and binding, although they can be annulled because of want of capacity or vitiated consent of one of the parties, but before alienation, they are effective and obligatory between the parties. The most essential feature is that it is binding until it is annulled by a competent court. Once it is executed there are only two possible alternatives left to the party who may invoke its voidable character to attack its validity or to convalidate it either by ratification or by prescription. Its validity may be attacked either directly by means of a proper action in court or indirectly by way of defense. The action itself is called annulment in order to distinguish it from an action for the rescission of rescissible contracts or from an action for the declaration of absolute nullity or inexistence of void or inexistent contracts, while the defense itself is called annulability or relative nullity in order to distinguish it from the defense of absolute nullity or inexistent in void or inexistent contracts or the defense of unenforceability in unenforceable contracts Rescission Merely produces that inefficacy, which did not exist essentially in the contract To be ineffective, needs no ratification Private interest alone goven Remedy; equity May be demanded even by 3rd parties affected by it

TOLENTINO: Nullity vs. Rescission Nullity As its name implies, declares the inefficacy which the contract already carries in itself To be cured, requires an act of ratification The direct influence of the public interest is noted Sanction; the law predominating in the former Can be demanded only by the parties to the contract

1. 2. 3.

TOLENTINO: Repentance is not a ground for nullification Characteristics: Their defect consists in the vitiation of consent of one of the contracting parties They are binding until they are annulled by a competent court They are susceptible of convalidation by ratification or by prescription Their defect or voidable character cannot be invoked by 3rd persons Rescissible Contracts The defect is external because it consists of damage or prejudice either to one of the contracting parties or to a 3 rd person The contract is not rescissible if there is no damage or

Voidable Contracts The defect is intrinsic because it consists of a vice which vitiates consent The contract is voidable even if there is no damage or

prejudice prejudice The annulability of the contract is based on the law. The rescissibility of the contract is based on equity. Rescission Annulment is not only a remedy but a sanction. Public interest is a mere remedy. Private interest predominates predominates The cause for annulment are different from the causes for rescission. Susceptible of ratification Not susceptible Annulment may be invoked only by a contracting party Rescission may be invoked either by a contracting party or by a 3rd person who is prejudiced. Art. 1390. The following contracts are voidable or annullable, even though there may have been no damage to the contracting parties: (1) Those where one of the parties is incapable of giving consent to a contract; (2) Those where the consent is vitiated by mistake, violence, intimidation, undue influence or fraud. These contracts are binding, unless they are annulled by a proper action in court. They are susceptible of ratification. (n) It must be observed that in a voidable contract all of the essential requisites for validity are present, although the requisite of consent is defective because one of the contracting parties does not possess the necessary legal capacity, or because it is vitiated by mistake, violence, intimidation, undue influence or fraud. If consent is absolutely lacking or simulated the contract is inexistent, not voidable. Whether a contract which the law considers as voidable has already been consummated or is merely executory is immaterial; it can always be annulled by a proper action in court. READ FELIPE VS. HEIRS OF ALDON (page. 521)

Art. 1391. The action for annulment shall be brought within four years. This period shall begin: In cases of intimidation, violence or undue influence, from the time the defect of the consent ceases. In case of mistake or fraud, from the time of the discovery of the same. And when the action refers to contracts entered into by minors or other incapacitated persons, from the time the guardianship ceases. (1301a) If the action is not commenced within such period, the right of the party entitled to institute the action shall prescribe. Should the defense also prescribe within the same period as the action for annulment? Although Art. 1391 speaks only of the action, Spanish commentators advance the view that the defense shall also prescribe after the lapse of 4 years, since the basis of the action and the basis of the defense are identical In Braganza vs. Villa Abrille, however, the SC declared that there is reason to doubt the pertinency of the period fixed by Art. 1391 of the Civil Code where minority is set up only as a defense to an action, without the minors asking for any positive relief from the contract. only an assumption but more just and logical i.e. Mrs. S borrowed P20,000 from PG. She and her 19-year old son, Mario, signed the promissory note for the loan, which note did not say anything about the capacity of the signers. Mrs. S made partial payments little by little. After 7 years, she died leaving a balance of P10,000 on the note. PG demanded payment from Mario who refused to pay. When sued for the amount, Mario raised the defense: that he signed the note when he was still a minor. Should the defense be sustained? Why? Answer No. 1 The defense should be sustained. Mario cannot be bound by his signature in the promissory note. It must be observed that the promissory note does not say anything about the capacity of the signers. In other words, there is no active fraud or misrepresentation; there is merely silence or constructive fraud or misrepresentation. It would have been different if the note says that Mario is of age. The principle of estoppel would then apply. Mario would not be allowed to invoke the defense of minority. The promissory note would then have all the effects of a perfectly valid note. Hence, as far as Marios share in the obligation is concerned, the promissory note is voidable because of minority. He cannot be absolved entirely from the monetary responsibility. Under the Civil Code, even if his written contract is voidable because of minority he shall make restitution to the extent that he may have been benefited by the money received by him (Art. 1399, CC). True, more than four years have already elapsed from the time that Mario had attained the age of 21. Apparently, his right to interpose the defense has already prescribed. It has been held, however, that where minority is sued as a defense and no positive relief is prayed for, the 4-year period (Art. 1391, CC) does not apply. Here Mario is merely interposing his minority as an excuse from liability. Answer No. 2 The defense should not be sustained. It must be noted that the action for annulment was instituted by PG against Mario when the latter was already 26 years old. Therefore, the right of Mario to invoke his minority as a defense has already prescribed. According to the CC, actions for annulment of voidable contracts shall prescribe after 4 years. In the case of contracts which are voidable by reason of minority or incapacity, the 4-year period shall be counted from the time the guardianship ceases (Art. 1391). The same rule should also be applied to the defense. In the instant case, since more than 4 years already elapsed from the time Mario had attained the age of 21, therefore, he can no longer interpose his minority as a defense. It would have been different if four year had not yet elapsed from the time Mario had attained the age of 21. Since there was no active fraud or misrepresentation on his part at the time of

execution of the promissory note, it is clear that the contract is voidable as far as he is concerned. In such case, the defense of minority should then be sustained. Art. 1392. Ratification extinguishes the action to annul a voidable contract. (1309a) Art. 1393. Ratification may be effected expressly or tacitly. It is understood that there is a tacit ratification if, with knowledge of the reason which renders the contract voidable and such reason having ceased, the person who has a right to invoke it should execute an act which necessarily implies an intention to waive his right. (1311a) Art. 1394. Ratification may be effected by the guardian of the incapacitated person. (n) Art. 1395. Ratification does not require the conformity of the contracting party who has no right to bring the action for annulment. (1312) Art. 1396. Ratification cleanses the contract from all its defects from the moment it was constituted. (1313) Besides prescription, the action for annulment of a voidable contract may also be extinguished by ratification. Ratification or confirmation the act or means by virtue of which efficacy is given to a contract which suffers from a vice of curable nullity. TOLENTINO: Confirmation is the act by which a person, entitled to bring an action for annulment, with knowledge of the cause of annulment and after it has ceased to exist, validates the contract either expressly or impliedly TOLENTINO: Ratification is the act of approving a contract entered into by another without the authorization of the person in whose name it was entered into, or beyond the scope of the authority of the former. The code makes no more distinction between confirmation and ratification. Requisites of Ratification: The contract should be tainted with a vice which is susceptible of being cured presupposes the existence of a vice in the contract because otherwise it would not have any object. Furthermore, such vice should be susceptible of being cured because otherwise the contract would be void or inexistent and not susceptible of confirmation. The confirmation should be effected by the person who is entitled to do so under the law implied from the provisions of Arts. 1394 and 1395 It should be effected with knowledge of the vice or defect of the contract Art. 1393. Since confirmation is above all a form of expressing the will, as such it requires, independently of the act to which it refers, the same conditions of freedom, knowledge and charity which consent also requires, although it does not require the conformity of the other party who has no right to invoke the nullity of the contract. If the contract is tainted with several vices, such as when it has been executed through mistake or fraud. In such case, if the person entitled to effect the confirmation ratifies or confirms the contract with knowledge of the mistake, but not of fraud, his right to ask for annulment is not extinguished thereby since the ratification or confirmation has only purged the contract of mistake, but not of fraud The cause of the nullity or defect should have already disappeared Ratification:

1. 2.

3.

4.

Express R. if, with knowledge of the reason which renders the contract voidable and such reason having ceased, the person who has a right to invoke it should expressly declare his desire to convalidate it, or what amounts to the same thing, to renounce his right to annul the contract. Tacit R. if, with knowledge of the reason which renders the contract voidable and such reason having ceased, the person who has a right to invoke it should execute an act which necessarily implies an intention to waive his right. Effects of ratification:

Art 1392 ratification extinguishes the action to annul the contract Art. 1396 it cleanses the contract of its defect from the moment it was constituted.

TOLENTINO: Retroactivity of Ratification its effects retroact to the moment where the contract was entered into. Art. 1397. The action for the annulment of contracts may be instituted by all who are thereby obliged principally or subsidiarily. However, persons who are capable cannot allege the incapacity of those with whom they contracted; nor can those who exerted intimidation, violence, or undue influence, or employed fraud, or caused mistake base their action upon these flaws of the contract. (1302a) 1. 2. Requisites to confer the necessary capacity for the exercise of the action for annulment: The plaintiff must have an interest in the contract That the victim and not the party responsible for the vice or defect must be the person who must assert the same. Generally, 3rd person cannot institute an action for its annulment. Exception according to SC, a person who is not a party obliged principally or subsidiarily under a contract may exercise an action for annulment of the contract if he is prejudiced in his rights with respect to one of the contracting parties, and can show the detriment which would positively result to him from the contract in which he has no intervention i.e. where the remaining partners of a partnership executed a chattel mortgage over the properties of the partnership in favor of a former partner to the prejudice of creditors of the partnership, the latter have a perfect right to file the action to nullity the chattel mortgage.

The second requisite is based on the well-known principle of equity that whoever goes to court must do so with clean hands. i.e. X, of age, entered into a contract with Y, a minor. X knew and the contract specifically stated the age of Y. May X successfully demand annulment of the contract? No. True that the contract is voidable because of the fact that at the time of the celebration of the contract, Y, the other contracting party, was a minor and such minority was known to X. i.e. Pedro sold a piece of land to his nephew Quintin, a minor. One month later, Pedro died. Pedros heirs then brought an action to annul the sale on the ground that Quintin was a minor and therefore without legal capacity to contract. If you are the judge, would you annul the sale? No. The CC in Art. 1397 is explicit. Persons who are capable cannot allege the incapacity of those with whom they contracted. The requisites are lacking, the second is not in the case.

Art. 1398. An obligation having been annulled, the contracting parties shall restore to each other the things which have been the subject matter of the contract, with their fruits, and the price with its interest, except in cases provided by law. In obligations to render service, the value thereof shall be the basis for damages. (1303a) Art. 1399. When the defect of the contract consists in the incapacity of one of the parties, the incapacitated person is not obliged to make any restitution except insofar as he has been benefited by the thing or price received by him. (1304) Art. 1398 obligation of mutual restitution. Interest refers to the legal interest. The benefit in Art. 1399 which obliges the incapacitated person to make restitution does not necessarily presuppose a material and permanent augmentation of fortune; it is sufficient if there has been a prudent and beneficial use by the incapacitated person of the thing which he has received. In order to determine this, it is necessary to know his necessities, his social position as well as his duties as a consequence thereof to others. It is clear that the proof of such benefit is cast upon the person who has capacity, since it is presumed in the absence of proof that no such benefit has accrued to the incapacitated person Art. 1399 cannot be applied to cases where the incapacitated person can still return the thing which he has received. TOLENTINO: Liability can even be based on Art. 20 and 21

Art. 1400. Whenever the person obliged by the decree of annulment to return the thing can not do so because it has been lost through his fault, he shall return the fruits received and the value of the thing at the time of the loss, with interest from the same date. (1307a) Art. 1401. The action for annulment of contracts shall be extinguished when the thing which is the object thereof is lost through the fraud or fault of the person who has a right to institute the proceedings. If the right of action is based upon the incapacity of any one of the contracting parties, the loss of the thing shall not be an obstacle to the success of the action, unless said loss took place through the fraud or fault of the plaintiff. (1314a) Art. 1402. As long as one of the contracting parties does not restore what in virtue of the decree of annulment he is bound to return, the other cannot be compelled to comply with what is incumbent upon him. (1308) 1. 2. 3. The loss of the thing which constitutes the object of the contract through the fault of the party whom the action for annulment may be instituted shall not, therefore, extinguish the action for annulment The only difference from an ordinary action for annulment is that, instead of being compelled to restore the thing, the defendant can only be compelled to pay the value thereof at the time of the loss. Where loss is due to fault of plaintiff the action for annulment is extinguished There are three modes whereby such action may be extinguished. They are: prescription Ratification Loss of the thing which is the object of the contract through the fraud or fault of the person who is entitled to institute the action If the loss was due to the fraud or fault of the plaintiff during his incapacity, the exception was applicable. The loss would not be an obstacle to the success of the action. If the person obliged by the decree of annulment to return the thing cannot do so because it has been lost through a fortuitous event, the contract can still be annulled, but with this difference the defendant can be held liable only for the value of the thing at the time of the loss, but without interest thereon. The defendant, not the plaintiff, must suffer the loss because he was still the owner of the thing at the time of the loss; he should, therefore pay the value of the thing, but not the interest therein because the loss was not due to his fault. According to Dr. Tolentino, if the plaintiff offers to pay the value of the thing at the time of its loss as a substitute for the thing itself, the annulment of the contract would still be possible, because, otherwise, we would arrive at the absurd conclusion that an action for annulment would in effect be extinguished by the loss of the thing through a fortuitous event.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Defective ContractsDokument136 SeitenDefective ContractsJanetGraceDalisayFabrero50% (2)

- Chapter 6 Notes Rescissible ContractsDokument9 SeitenChapter 6 Notes Rescissible ContractsGin Francisco100% (1)

- The Essential Features of The Different Classes of Defective Contracts AreDokument5 SeitenThe Essential Features of The Different Classes of Defective Contracts Aremaria luzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Voidable ContractsDokument4 SeitenVoidable Contractspreiquency100% (1)

- CHAPTER 6 - Rescissible Contracts (Arts. 1380-1389)Dokument13 SeitenCHAPTER 6 - Rescissible Contracts (Arts. 1380-1389)Danika S. Santos85% (13)

- OBLICON Defective Contracts MatrixDokument4 SeitenOBLICON Defective Contracts Matrixdeeyanne1803100% (1)

- ObliCon BAR Q&ADokument106 SeitenObliCon BAR Q&AMaan50% (4)

- Table of Defective ContractsDokument2 SeitenTable of Defective Contractsgelaaiiii100% (9)

- Obligation and Contrcacts SummaryDokument7 SeitenObligation and Contrcacts SummaryRaffy Roncales90% (29)

- Defective ContractsDokument9 SeitenDefective ContractsNorman NgNoch keine Bewertungen

- OBLICON Definition of TermsDokument5 SeitenOBLICON Definition of TermsDia Santos96% (25)

- Quiz - 4 Kinds of Defects of A ContractDokument9 SeitenQuiz - 4 Kinds of Defects of A ContractjeffdelacruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- ObliCon - ART 1255 - ART 1304Dokument7 SeitenObliCon - ART 1255 - ART 1304Cazia Mei Jover100% (2)

- Kinds of ObligationDokument428 SeitenKinds of ObligationMrcharming Jadraque82% (39)

- HW1Dokument4 SeitenHW1Rigel Zabate50% (2)

- Comparative Table of Defective Contracts - RevDokument2 SeitenComparative Table of Defective Contracts - Revcm ortega100% (2)

- Obligations and ContractsDokument42 SeitenObligations and Contractshanasadako100% (76)

- Oblicon Midterm ReviewerDokument18 SeitenOblicon Midterm Reviewerkatreena ysabelle100% (15)

- Defective ContractsDokument3 SeitenDefective Contractsisangbedista100% (2)

- Oblicon TeasersDokument68 SeitenOblicon TeasersJanetGraceDalisayFabrero43% (7)

- Chapter 7 VoidableDokument9 SeitenChapter 7 VoidableRafeliza CabigtingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reviewer - Reformation of InstrumentDokument5 SeitenReviewer - Reformation of InstrumentBonna De RuedaNoch keine Bewertungen

- PUP Notes On Obligation and ContractDokument29 SeitenPUP Notes On Obligation and ContractJayrick James Arisco100% (1)

- Obligation & Contracts (3 Special Forms of Payment)Dokument4 SeitenObligation & Contracts (3 Special Forms of Payment)Rachel Almadin80% (5)

- Rescissible ContractsDokument8 SeitenRescissible ContractsCath OfilasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oblicon Midterm ExamDokument3 SeitenOblicon Midterm ExamSamuel Argote33% (3)

- Sample Questions and Answers in Extinguishment and ContractsDokument17 SeitenSample Questions and Answers in Extinguishment and ContractsEthel Joi Manalac Mendoza67% (3)

- Oblicon - Extinguishment of ObligationDokument9 SeitenOblicon - Extinguishment of ObligationBeejay BenitezNoch keine Bewertungen

- CHAPTER 3, SEC. 1 (Arts. 1179-1192)Dokument5 SeitenCHAPTER 3, SEC. 1 (Arts. 1179-1192)Lyan David Marty Juanico100% (3)

- Reviewer ObliconDokument17 SeitenReviewer ObliconRussel SirotNoch keine Bewertungen

- CHAPTER 6 (Arts. 1380-1389)Dokument6 SeitenCHAPTER 6 (Arts. 1380-1389)Kaye RabadonNoch keine Bewertungen

- CHAPTER 3 SEC. 5 Arts. 1223 1225Dokument6 SeitenCHAPTER 3 SEC. 5 Arts. 1223 1225Vince Llamazares Lupango100% (6)

- MCQ For Obligations and ContractsDokument6 SeitenMCQ For Obligations and ContractsMei Mei75% (4)

- Extinguishment of Obligation - Novation - Notes - Atty LargoDokument9 SeitenExtinguishment of Obligation - Novation - Notes - Atty LargoStephanie Dawn Sibi Gok-ong100% (3)

- Contracts and ObligationsDokument4 SeitenContracts and ObligationsNerissa Serrano0% (1)

- Joint and Solidary Obligation (Simplified)Dokument2 SeitenJoint and Solidary Obligation (Simplified)Stefhanie Khristine Pormanes89% (9)

- CivLawRev QnA Part 2Dokument8 SeitenCivLawRev QnA Part 2Stan AmistadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 4, Sec.1: Payment or PerformanceDokument2 SeitenChapter 4, Sec.1: Payment or Performanceazi montefalcoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Table Matrix For Defective ContractsDokument3 SeitenTable Matrix For Defective ContractsJanetGraceDalisayFabrero100% (1)

- Bar ObliconDokument63 SeitenBar ObliconAshwini Go100% (2)

- Chapter 6 Notes Rescissible ContractsDokument4 SeitenChapter 6 Notes Rescissible ContractsGin Francisco80% (5)

- 4 Classes of Defective ContractsDokument3 Seiten4 Classes of Defective ContractsPauljohn Soriano67% (3)

- 4 Rescissible ContractsDokument11 Seiten4 Rescissible ContractsAlpheus Shem ROJASNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stages of A ContractDokument10 SeitenStages of A ContractThereseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reviewer For Articles 1390Dokument5 SeitenReviewer For Articles 1390Ellaine CascarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- ObliCon-Activity 2Dokument2 SeitenObliCon-Activity 2Angela Pabico RosarioNoch keine Bewertungen

- ASSIGNMENT#3Dokument3 SeitenASSIGNMENT#3DJ AXELNoch keine Bewertungen

- ContractsDokument6 SeitenContractsChristopher DizonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary of Defective Contracts Obligations and ContractsDokument9 SeitenSummary of Defective Contracts Obligations and ContractsRoy Matthew BorromeoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Att 1362544744505 Characteristic of ContractDokument4 SeitenAtt 1362544744505 Characteristic of Contractricohizon99Noch keine Bewertungen

- Rescissible ContractsDokument6 SeitenRescissible ContractsblablablaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rescissible ContractDokument2 SeitenRescissible ContractCATHY ROSALESNoch keine Bewertungen

- OBLICON May 16 With CommentDokument106 SeitenOBLICON May 16 With CommentPaula ValienteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Classes of Defective ContractsDokument17 SeitenClasses of Defective Contractszehra我Noch keine Bewertungen

- 1401 To 1410Dokument6 Seiten1401 To 1410Rubz JeanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kinds of Defective ContractsDokument2 SeitenKinds of Defective ContractsJANET MARIE MERCADONoch keine Bewertungen

- Classes of Defective ContractsDokument17 SeitenClasses of Defective ContractsJefferson PagandahanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Learning Module: General Provisions of Contracts: and Answering The Exercises. Honestly. AccountDokument5 SeitenLearning Module: General Provisions of Contracts: and Answering The Exercises. Honestly. AccountNCF- Student Assistants' OrganizationNoch keine Bewertungen

- Defective ContractsDokument8 SeitenDefective Contractsanon_965241988100% (1)

- Justin V. Torres 1G: Defective ContractsDokument4 SeitenJustin V. Torres 1G: Defective ContractsJustin Torres100% (1)

- Case Full Text LaborDokument25 SeitenCase Full Text LaborRoselle CasiguranNoch keine Bewertungen

- PALE Case DigestDokument11 SeitenPALE Case DigestRoselle CasiguranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reaction PaperDokument2 SeitenReaction PaperRoselle Casiguran100% (1)

- Legal Counselling ReportDokument7 SeitenLegal Counselling ReportRoselle CasiguranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oblicon Reviewer Final DDokument119 SeitenOblicon Reviewer Final DRoselle CasiguranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leg Coun Paper 3Dokument2 SeitenLeg Coun Paper 3Roselle CasiguranNoch keine Bewertungen

- ListDokument1 SeiteListRoselle CasiguranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cromwell Reaction PapeerDokument1 SeiteCromwell Reaction PapeerRoselle CasiguranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oblicon Reviewer Final DDokument119 SeitenOblicon Reviewer Final DRoselle CasiguranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Outline CorpoDokument6 SeitenOutline CorpoRoselle CasiguranNoch keine Bewertungen

- UnthinkableDokument2 SeitenUnthinkableRoselle CasiguranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case 1 EvidDokument4 SeitenCase 1 EvidRoselle CasiguranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bobongan CaseDokument2 SeitenBobongan CaseRoselle CasiguranNoch keine Bewertungen

- PALE Case DigestDokument11 SeitenPALE Case DigestRoselle CasiguranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Defective ContractsDokument24 SeitenDefective ContractsRoselle CasiguranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Torts SyllabusDokument6 SeitenTorts SyllabusRoselle CasiguranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Torts SyllabusDokument6 SeitenTorts SyllabusRoselle CasiguranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elec Case DigestDokument5 SeitenElec Case DigestRoselle CasiguranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Codal - ContractsDokument6 SeitenCodal - ContractsRoselle CasiguranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oblicon General Provisions ReviewerDokument15 SeitenOblicon General Provisions ReviewerRoselle CasiguranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Petition For Administrative ReconstitutionDokument2 SeitenPetition For Administrative Reconstitutionmpt2000100% (1)

- Excel Cash Book Extra RowsDokument28 SeitenExcel Cash Book Extra RowsppjobNoch keine Bewertungen

- Taxation IIDokument72 SeitenTaxation IIArnold OniaNoch keine Bewertungen

- REPORT ON Allahabad Bank BY ANUP SINGHDokument62 SeitenREPORT ON Allahabad Bank BY ANUP SINGHAnup Singh67% (6)

- Project Report of Ratio AnalysisDokument56 SeitenProject Report of Ratio AnalysisZahid Bhat100% (1)

- Metrobank Vs CADokument2 SeitenMetrobank Vs CAManuel LuisNoch keine Bewertungen

- ABC Limited - PPT NBNDokument19 SeitenABC Limited - PPT NBNNagarajNadigNoch keine Bewertungen

- AttachmentDokument60 SeitenAttachmentTahseen banuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 113-Land Act Cap. 113 R.E. 2019 PDFDokument206 SeitenChapter 113-Land Act Cap. 113 R.E. 2019 PDFEsther MaugoNoch keine Bewertungen

- SLF065 MultiPurposeLoanApplicationForm V03 PDFDokument2 SeitenSLF065 MultiPurposeLoanApplicationForm V03 PDFElle VillanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lausa vs. QuilatonDokument23 SeitenLausa vs. QuilatonJoel G. AyonNoch keine Bewertungen

- General Management Project - Onkar Adhikari (MMS-16-01)Dokument81 SeitenGeneral Management Project - Onkar Adhikari (MMS-16-01)NAMRATA MAKWANANoch keine Bewertungen

- Financial Modelling - ExcelDokument39 SeitenFinancial Modelling - ExcelEric ChauNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sme LoanDokument3 SeitenSme LoanHemrajSainiNoch keine Bewertungen

- From Lehman To Demonetization - Tamal BandyopadhyayDokument256 SeitenFrom Lehman To Demonetization - Tamal BandyopadhyayfilmNoch keine Bewertungen

- Application To Stay Closing of Cases 10 29 09Dokument88 SeitenApplication To Stay Closing of Cases 10 29 09sturdonNoch keine Bewertungen

- My ReportDokument48 SeitenMy ReportSaik Sadat Ibna IslamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manager, ICICI Bank V Prakash Kaur and OrsDokument10 SeitenManager, ICICI Bank V Prakash Kaur and Orsarunav_guha_royroyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Check List Housing Loan - SBIDokument15 SeitenCheck List Housing Loan - SBIVigneshwaran NadanathangamNoch keine Bewertungen

- LIC Form Griha PrakashDokument6 SeitenLIC Form Griha PrakashVaibhavRanjankarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Individual Paper Income Tax Return 2015Dokument23 SeitenIndividual Paper Income Tax Return 2015marrukhjNoch keine Bewertungen

- Daniel Afedzi PGSM ThesisDokument124 SeitenDaniel Afedzi PGSM ThesisAfedzi Daniel100% (1)

- Veritext Reporting Company 212-267-6868 516-608-2400Dokument19 SeitenVeritext Reporting Company 212-267-6868 516-608-2400Chapter 11 DocketsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Traders Royal Bank Vs Cuison LumberDokument2 SeitenTraders Royal Bank Vs Cuison LumberJonathan DancelNoch keine Bewertungen

- G.R. No. 176043 January 15, 2014 Spouses Bernadette and Rodulfo Vilbar, Petitioners, ANGELITO L. OPINION, RespondentDokument11 SeitenG.R. No. 176043 January 15, 2014 Spouses Bernadette and Rodulfo Vilbar, Petitioners, ANGELITO L. OPINION, RespondentJuris FormaranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Career Test Result - Free Career Test Taking Online at 123testDokument5 SeitenCareer Test Result - Free Career Test Taking Online at 123testapi-266271079Noch keine Bewertungen

- Outline FRIADokument30 SeitenOutline FRIAhellojdey100% (1)

- Banking Law & PracticeDokument12 SeitenBanking Law & PracticeShams TabrezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fria 2018Dokument19 SeitenFria 2018mjpjoreNoch keine Bewertungen

- US Internal Revenue Service: 2004p1212 Sect I-Iii TablesDokument133 SeitenUS Internal Revenue Service: 2004p1212 Sect I-Iii TablesIRSNoch keine Bewertungen