Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

5 Freud Jokes and Their Relation To The Unconsciousness

Hochgeladen von

greenandsubmarineOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

5 Freud Jokes and Their Relation To The Unconsciousness

Hochgeladen von

greenandsubmarineCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

5.

Freud, Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious

(1) Sigmund Freuds Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious [1905] proposes a psychological account of why we make jokes, and why they cause us pleasure. He sees them as one of the ways in which we allow repressed topics and feelings to be given indirect expression; and he sees the pleasure that we express in laughter as a form of relief at being able to overcome repression. (In other works by Freud, he discusses dreams and slips of the tongue, or so-called Freudian slips, as similar ways in which repression can be indirectly overcome.) For Freud, this explains why so many jokes have a sexual or an aggressive or indeed a sexually aggressive -- content, since these are the instincts that we are least willing to admit to directly. The following discussion focuses on Freuds idea of the purpose behind hostile jokes: Though as children we are still endowed with a powerful inherited disposition to hostility, we are later taught by a higher personal civilization that it is an unworthy thing to use abusive language; and even where fighting has in itself remained permissible, the number of things which may not be employed as methods of fighting has extraordinarily increased. Since we have been obliged to renounce the expression of hostility by deeds -- held back by the passionless third person, in whose interest it is that personal security shall be preserved -- we have just as in the case of sexual aggressiveness, developed a new technique of invective, which aims at enlisting this third person against our enemy. By making our enemy small, inferior, despicable or comic, we achieve in a roundabout way the enjoyment of overcoming him -- to which the third person, who has made no efforts, bears witness by his laughter. We are now prepared to realize the part played by jokes in hostile aggressiveness. A joke will allow us to exploit something ridiculous in our enemy which we could not, on account of obstacles in the way, bring forward openly or consciously; once again, then, the joke will evade restrictions and open sources of pleasure that have become inaccessible The prevention of invective or of insulting rejoinders by external circumstances is such a common case that tendentious jokes are especially favoured in order to make aggressiveness or criticism possible against persons in exalted positions who claim to exercise authority. The joke then represents a rebellion against that authority, a

liberation from its pressure. The charm of caricatures lies in this same factor: we laugh at them even if they are unsuccessful simply because we count rebellion against authority as a merit. At this point in the discussion, Freud recognises a problem in his theory, which is that quite often the individuals we laugh at in jokes arent important people at all. As an example, he reconsiders Jewish jokes about Schadchen or traditional marriage-brokers, who are very lowly figures in the community but who strike at something more important, as he puts it, namely the serious institution of marriage upon which their work is based, and the serious underlying questions of sexual attraction and sexual relations. An earlier example of a Schadchen joke goes as follows: The bridegroom was most disagreeably surprised when the bride was introduced to him, and drew the broker on one side and whispered his remonstrances: Why have you brought me here? he asked reproachfully. Shes ugly and old, she squints and has bad teeth and bleary eyes You neednt lower your voice, interrupted the broker, shes deaf as well. [pp.103f.] Freuds argument continues: If we bear in mind the fact that tendentious jokes are so highly suitable for attacks on the great, the dignified and the mighty, who are protected by internal inhibitions and external circumstances from direct disparagement, we shall be obliged to take a special view of certain groups of jokes which seem to be concerned with inferior and powerless people. [Does] what we have learnt of the nature of tendentious jokes on the one hand and on the other hand our great enjoyment of these stories fit in with the paltriness of the people whom these jokes seem to laugh at? Are they worthy opponents of the jokes? Is it not rather the case that the jokes only put forward marriage-brokers in order to strike at something more important? [They] are the better jokes because they are in a position to conceal not only what they have to say but also the fact that they have something forbidden to say The whole of the ridicule now falls upon the parents who think this swindle is justified in order to get their daughter a husband, upon the pitiable condition of girls who let themselves be married upon such terms, and upon the disgracefulness of marriage contracted on such a basis The popular mind knows the sacredness of marriages after they have been

contracted is grievously affected by the thought of what happened at the time when they were arranged. [Sigmund Freud, Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious, Penguin Freud Library, vol.6, pp.147-51] (2) A psychiatrist joke: A man goes to see a psychiatrist, saying hes worried about being obsessed with sex. The psychiatrist decides to try a Rorschach inkblot test. He shows the patient the first inkblot and the patient says it looks like a couple making love on the beach. When he shows him the second, the patient says it looks like a couple making love under the shower. With the third, he says it looks like a couple making love in the park. At the end of the test the psychiatrist looks over his notes, and says, Well yes, you do seem to have a strong preoccupation with sex. The patient replies, You can talk. Youre the one with all the dirty pictures.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- An Essay on Laughter: Its Forms, Its Causes, Its Development and Its ValueVon EverandAn Essay on Laughter: Its Forms, Its Causes, Its Development and Its ValueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Humor, Psychoanalysis and ResentmentDokument15 SeitenHumor, Psychoanalysis and ResentmentNatela HaneliaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Historical Views of HumourDokument18 SeitenHistorical Views of HumourJuliana SechinatoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thesis Statement On ComedyDokument4 SeitenThesis Statement On Comedystephaniekingmanchester100% (2)

- An Approach To Analyzing JokesDokument6 SeitenAn Approach To Analyzing Jokesnelsonmugabe89Noch keine Bewertungen

- Topic 4Dokument2 SeitenTopic 4Марина СветличнаяNoch keine Bewertungen

- My Complaint About Scribed 13Dokument5 SeitenMy Complaint About Scribed 13jayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shaft HumorDokument12 SeitenShaft HumorJesica LengaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Taking Humour (Ethics) Seriously, But Not Too Seriously PDFDokument20 SeitenTaking Humour (Ethics) Seriously, But Not Too Seriously PDFGraceNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Superiority TheoryDokument21 SeitenThe Superiority TheoryDexter BNoch keine Bewertungen

- Defamation PDFDokument50 SeitenDefamation PDFKartik GuptaNoch keine Bewertungen

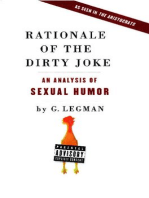

- Rationale of the Dirty Joke: An Analysis of Sexual HumorVon EverandRationale of the Dirty Joke: An Analysis of Sexual HumorBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (14)

- Herzog - Defaming The DeadDokument288 SeitenHerzog - Defaming The DeadShafia RahmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thorson - A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The MorgueDokument16 SeitenThorson - A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The MorgueAnonymous Yrp5vpfXNoch keine Bewertungen

- Negotiating Identity in Sukumar Ray's Literary NonsenseDokument25 SeitenNegotiating Identity in Sukumar Ray's Literary NonsenseSakshi SinhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- My Complaint About Scribed 12Dokument4 SeitenMy Complaint About Scribed 12jayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Freud and The Language of Humour: WeblinksDokument4 SeitenFreud and The Language of Humour: Weblinksdivecha_shivamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Irony Thesis ExamplesDokument7 SeitenIrony Thesis Exampleshmnxivief100% (2)

- Meg 3 em PDFDokument10 SeitenMeg 3 em PDFFirdosh Khan100% (4)

- 13 Ang 1 e Se 1Dokument8 Seiten13 Ang 1 e Se 1Đinh Kiều TrangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Steven PinkerDokument3 SeitenSteven PinkerDianaBarbbuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dark Comedy: Bringing Light Upon Society David Magat Glen Allen High SchoolDokument15 SeitenDark Comedy: Bringing Light Upon Society David Magat Glen Allen High Schoolapi-285975003Noch keine Bewertungen

- Blin-On Laughter and Ethics (2019)Dokument21 SeitenBlin-On Laughter and Ethics (2019)jbpicadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology: J / Wrestled With The Problem of Humor, There Is Still ConsiderDokument25 SeitenThe Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology: J / Wrestled With The Problem of Humor, There Is Still ConsiderDan NamiseNoch keine Bewertungen

- HumourDokument17 SeitenHumourDiana Hogea-ȚuscanuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Silence and Responsibility - Ishani MaitraDokument21 SeitenSilence and Responsibility - Ishani Maitraraumel romeroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Schwartz OpEd 1Dokument4 SeitenSchwartz OpEd 1Eric SchwartzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Appeal To PityDokument3 SeitenAppeal To PityIan PotenteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Frankfurt - Faintest PassionDokument13 SeitenFrankfurt - Faintest PassionJames L. KelleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Is Offensive Comedy Hurting UsDokument2 SeitenIs Offensive Comedy Hurting Usapi-283935315Noch keine Bewertungen

- Attardo - Humor and Irony in InteractionDokument22 SeitenAttardo - Humor and Irony in InteractionJovana KovacevicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ferris Owen Sposito Neg Toc Round3Dokument40 SeitenFerris Owen Sposito Neg Toc Round3Truman ConnorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alain de Botton - ON ARGUINGDokument3 SeitenAlain de Botton - ON ARGUINGFabián BarbaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Michael Billig - Humour and HatredDokument42 SeitenMichael Billig - Humour and Hatredalyx930Noch keine Bewertungen

- Kris 2005 The Lure of HypocrisyDokument16 SeitenKris 2005 The Lure of Hypocrisyfadlil munawwar manshur MSNoch keine Bewertungen

- Davies 2009Dokument14 SeitenDavies 2009Integrante TreceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Candide Reading QuestionsDokument8 SeitenCandide Reading QuestionsSteven TruongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dramatic Irony Thesis StatementDokument8 SeitenDramatic Irony Thesis Statementfjgjdhzd100% (1)

- You Are Triggering Me! The Neo-Liberal Rhetoric of Harm, Danger and Trauma - Bully BloggersDokument84 SeitenYou Are Triggering Me! The Neo-Liberal Rhetoric of Harm, Danger and Trauma - Bully BloggersMelanieShiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philosophy Paper On HumorDokument6 SeitenPhilosophy Paper On Humorapi-581247558Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Senses of HumorDokument3 SeitenThe Senses of HumorLook UpNoch keine Bewertungen

- Henri Bergson: Collected Works: Laughter, Time and Free Will, Creative Evolution, Matter and Memory, Meaning of the War & DreamsVon EverandHenri Bergson: Collected Works: Laughter, Time and Free Will, Creative Evolution, Matter and Memory, Meaning of the War & DreamsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Freud, Sigmund - HumorDokument10 SeitenFreud, Sigmund - HumorTory EtgardtNoch keine Bewertungen

- The SeductionDokument12 SeitenThe SeductionEsmeralda ArredondoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Debating Rape Jokes Vs Rape Culture Framing and Counter Framing Misogynistic ComedyDokument19 SeitenDebating Rape Jokes Vs Rape Culture Framing and Counter Framing Misogynistic Comedynelsonmugabe89Noch keine Bewertungen

- WOOSDA 4v2Dokument3 SeitenWOOSDA 4v2elipot2023Noch keine Bewertungen

- Achildisbeaten Freud AnnaandtherepressionofautosexualityDokument4 SeitenAchildisbeaten Freud Annaandtherepressionofautosexualitygaston.1001Noch keine Bewertungen

- Critical Thinking For 2 Year Student: University of Danang University of Foreign Language Studies Department of EnglishDokument53 SeitenCritical Thinking For 2 Year Student: University of Danang University of Foreign Language Studies Department of EnglishHung nguNoch keine Bewertungen

- Embarrassing Moment EssayDokument8 SeitenEmbarrassing Moment Essaymrmkiwwhd100% (3)

- Marbury Vs Madison EssayDokument4 SeitenMarbury Vs Madison Essayb72d994z100% (2)

- Essay About A PictureDokument8 SeitenEssay About A Pictured3gpmvqw100% (2)

- Fallacies Unit 3Dokument32 SeitenFallacies Unit 3Ali SyedNoch keine Bewertungen

- 15 Logical Fallacies You Should Know Before Getting Into A DebateDokument10 Seiten15 Logical Fallacies You Should Know Before Getting Into A DebateJohn Patrick De CastroNoch keine Bewertungen

- TYE-BAN1207 wk10 HumourDokument2 SeitenTYE-BAN1207 wk10 HumourEnglish beeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Double-Dealer: "Courtship is to marriage, as a very witty prologue to a very dull play."Von EverandThe Double-Dealer: "Courtship is to marriage, as a very witty prologue to a very dull play."Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (5)

- Minsky Jokes CognitiveDokument23 SeitenMinsky Jokes CognitivezxcvvcxzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anger As A Primary EmotionDokument6 SeitenAnger As A Primary EmotionSilvana DiaconescuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary of Sigmund Freud'S Psychosexual Stages andDokument8 SeitenSummary of Sigmund Freud'S Psychosexual Stages andgheljoshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Symbolic - LACANDokument9 SeitenSymbolic - LACANMocanu AlinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literary Criticism, Approaches and TheoriesDokument35 SeitenLiterary Criticism, Approaches and TheoriesJayrold Balageo MadarangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Forgetting The Past - Gavin LucasDokument13 SeitenForgetting The Past - Gavin LucasElla Lewis-Williams0% (1)

- THEOPERDokument9 SeitenTHEOPERGene Ann ParalaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lost in The Archives Edited by Rebecca Comay.Dokument4 SeitenLost in The Archives Edited by Rebecca Comay.madequal2658Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Radical Humanism of Erich Fromm PDFDokument256 SeitenThe Radical Humanism of Erich Fromm PDFGrace Carrasco100% (4)

- Janusian Thinking As A Psychological ProcessDokument23 SeitenJanusian Thinking As A Psychological ProcessRicardo GarciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Albert Ellis Reason and Emotion in PsychotherapyDokument456 SeitenAlbert Ellis Reason and Emotion in PsychotherapyCristian Catalina100% (2)

- Bloom, Internalization of Quest RomanceDokument12 SeitenBloom, Internalization of Quest RomanceHeron SaltsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Psychoanalysis & Film NoirDokument20 SeitenPsychoanalysis & Film NoirChristopher James Wheeler100% (13)

- Educational Psychology - Module 3 PDFDokument25 SeitenEducational Psychology - Module 3 PDFMulenga Levy ChunguNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theodore L. Dorpat - Gaslighting, The Double Whammy, Interrogation and Other Methods of Covert Control in Psychotherapy and Analysis-Jason Aronson, Inc. (1996)Dokument304 SeitenTheodore L. Dorpat - Gaslighting, The Double Whammy, Interrogation and Other Methods of Covert Control in Psychotherapy and Analysis-Jason Aronson, Inc. (1996)Miguel FloresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pregnancy Ways Aggressor: MeansDokument2 SeitenPregnancy Ways Aggressor: MeansArgenis SalinasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit Plan For WebsiteDokument32 SeitenUnit Plan For Websiteapi-276416956Noch keine Bewertungen

- Freud - SchreberDokument71 SeitenFreud - Schreberneculai.daniela78771Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Psychoanalysis of The Gothic ElementDokument43 SeitenThe Psychoanalysis of The Gothic ElementZainab HanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Role of Language in The Development of The Self Ii: Thoughts and WordsDokument22 SeitenThe Role of Language in The Development of The Self Ii: Thoughts and WordsAasim KarbhariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anglo American Modern LiteratureDokument134 SeitenAnglo American Modern LiteratureJelena NikolicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Freud-Names of The Analysts PDFDokument72 SeitenFreud-Names of The Analysts PDFIvan AndreeNoch keine Bewertungen

- GE6104 Gender and SocietyDokument6 SeitenGE6104 Gender and SocietyEun HyeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Psychoanalyzing "The Black Cat": The Journey From Emotional Transference To Displays of PsychopathyDokument6 SeitenPsychoanalyzing "The Black Cat": The Journey From Emotional Transference To Displays of PsychopathyIntan GustinarlaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rene Van Der Veer - The Vygotsky Reader (1994) PDFDokument384 SeitenRene Van Der Veer - The Vygotsky Reader (1994) PDFPablo JacintoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 1 UTSDokument6 SeitenModule 1 UTSAngel PicazoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 978-0135173572 Development AcrossDokument83 Seiten978-0135173572 Development AcrossReccebacaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Buddhist Perspectives On Psychiatric EthicsDokument15 SeitenBuddhist Perspectives On Psychiatric EthicsJSALAMONENoch keine Bewertungen

- 278-316 CH08 61939Dokument39 Seiten278-316 CH08 61939aravind100% (2)

- H ThesisDokument87 SeitenH ThesisRenata GeorgescuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Freud vs. HorneyDokument6 SeitenFreud vs. Horneygag412100% (1)

- Archetypes Along JungDokument35 SeitenArchetypes Along JungEurípides Burgos100% (8)