Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Brief 027

Hochgeladen von

mayelgebalyOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Brief 027

Hochgeladen von

mayelgebalyCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Measuring & Managing Performance in Education

by Jenny Ozga No. 27, February 2003

Policy-makers in Scotland are using performance management and measurement in a number of ways, in particular, as part of their efforts to raise pupil attainment and improve teacher performance. This Briefing looks at some of the assumptions that underpin the current approach to performance management and measurement. It considers issues about the reliability of these measurements, the appropriateness of using targets and indicators to measure and manage the performance of pupils and schools, and the likely impact on pupils and teachers.

Performance management has become the key instrument used by policy-makers to improve the education system, to raise levels of attainment and to increase the accountability of teachers. Performance management uses indicators such as pupil test scores to rank pupils, schools and counties and to generate Performance Targets that are then are used to manage performance. There is a danger that quantitative indicators of performance that can easily be measured and ranked eg pupils examination performance, are given greater significance by policy-makers than other, less easily measured, aspects of education. The ranking of educational performance of different countries may risk reducing the capacity of national systems to design the most appropriate curriculum and approaches for their students. Scotlands approach to performance management has attempted to bring quantitative and qualitative indicators together, notably in school self-evaluation. This approach is continued in respect of the new National Priorities, but quantitative indicators may still become dominant. Quantitative measurements of pupil and school performance currently in use by policy-makers are not sufficiently sophisticated to produce an accurate picture of teaching and learning in Scottish schools, and may over-simplify or distort a complex picture. Current performance management practices may reduce real le arning in Scottish schools and may most adversely affect those pupils already at risk of educational failure. But performance management has the potential to contribute to social inclusion if appropriate indicators are developed that help identify need and support appropriate interventions.

} } } } }

Introduction: The Growth of Performance Management in Education The use of indicators of performance as a way of managing and improving performance in education is now so widespread across schools, colleges and universities that it is difficult to imagine educational life without them. Yet they are relatively recent in their current form and differ in significant ways from previous practice, for example, providing data on examination success rates. Policy-makers have always collected data on the functioning of education systems, and have drawn on these data to monitor systems, identify trends and promote change. Performance management in its current form, however, has origins in anxiety about underperformance in education in an increasingly competitive global economic environment. Policy-makers in the UK have seen performance management as a mechanism for putting pressure on the education system to force it to improve across the board and to address the persistent tail of underachievement. There has been a related policy goal of shifting teachers from a perceived overemphasis on the teaching process to a stronger focus on attainment outcomes, together with a desire to increase the accountability of the teaching profession and so increase value for money. The Principles of Performance Management Performance management is a means of auditing and managing system-wide activity. Organisations are encouraged to raise their levels of performance, and manage their staff and customers more tightly to achieve better outputs and outcomes and avoid appearing at the bottom of a league table. Its core assumptions are that performance levels in the public sector can be raised; that this is desirable and necessary; and that evaluation on both an individual and comparative basis will promote improvement. Thus: is this school efficient and effective? Is this school more efficient and effective than its neighbour? Is our school system more efficient and effective than that of Finland? Poor position in a league table may have direct resource consequences or may indirectly reduce resources through its effects on consumer (parent or student) choice. In England the introduction of performance related pay means that poor performance, as indicated by pupil test scores, may be taken into account in appraising teacher performance and reviewing pay. However advocates of these measurements of success and failure are reluctant to acknowledge their limitations; the most obvious being that these are statistical artefacts: league tables run from top to bottom and there will thus always be a bottom 20%.

A Distinctive Approach Performance Management

in

Scotland

to

There has been a distinctively Scottish attempt to combine self-evaluation and performance management using performance indicators linked to school selfevaluation, notably in How Good is our School? This seeks to maintain local and school-based elements of evaluation and to combine quantitative and qualitative data to arrive at indicators of quality. For example, examination performance might be combined with data on teachers or parents views to construct the indicators of quality. The evaluation strategy of the new National Priorities in Education also uses this combination of approaches. These National Priorities set out the main areas for development in Scottish education and identify ways in which progress towards achieving these aims can be measured. The Priorities were established in a context of public discussion and debate about the future of Scottish education, and reflect an attempt to combine the pursuit of improved performance in the international competitive arena with the promotion of a distinctively Scottish ethos. Schools are encouraged to carry out rigorous selfevaluation of their progress towards achievement of the targets associated with the five National Priority Areas: Achievement and Attainment, Framework for Learning, Inclusion and Equality, Values and Citizenship, and Learning for Life. The process seeks to retain different types of indicators of performance (hard and soft measures), and also tries to keep the three levels of the system in play (national, local and school-level). An Emphasis on Quantitative Indicators The Scottish approach is an interesting and potentially creative version of performance management, but there is a danger that, in the overall context of competition, policy-makers will focus on the Priority Areas where progress can most readily be quantified (ie Achievement and Attainment) and place less emphasis on those Priority Areas such as Values and Citizenship, or Inclusion and Equality where progress is more difficult to assess and measure. It is likely that quantifiable indicators will assume greater importance and significance for the public and for policy-makers because they appear to be reliable and straightforward. They can be easily translated into targets, and progress towards them represented as trends. Yet their reliability is open to question, and their straightforwardness m cover their inadequacy ay in describing real world complexity. Even within the Achievement and Attainment Priority Area, the statistical information from which attainment targets for schools and local authorities is derived is open to

the criticism that it does not accurately estimate the schools contribution to pupil progress after taking account of differences in intake ie it does not give an accurate picture of value added. As Linda Croxford argues in Briefing 26, Scottish education does not yet have appropriate measures that enable the sources of inequalities in attainment to be identified and targeted. Possible techniques do exist but are not yet in widespread use. Meanwhile reliance on inadequate statistical models and measurements may encourage policy-makers and politicians to simplify complex problems and relationships while appearing to be guided by hard evidence. The growth of the idea of evidence-based policy may contribute to reliance on superficially robust indicators. Teaching to the Test and Examinationled Learning? The risk that performance management, and its repertoire of indicators and targets, focuses attention on pupil attainment at the expense of less easily quantifiable measures has been pointed out by a number of commentators. The focus on what can be measured pupils examination performance - places a very high value indeed on these measures of attainment. That high value is itself open to question as examinations are not necessarily good indicators of what pupils have le arned. Questions may also be raised about the desirability of examination-led learning in a context of rapid change and the need to develop independent and flexible learners. There are other concerns about the possible impact of testing and measurement on processes of classroom teaching and learning. Soucek, for example, argues that pupils and teachers become preoccupied with achieving technical success, at the expense of emotional investment in learning, with its associated intrinsic satisfactions and rewards. The task of learning, Soucek argues, is not understood in this context by either the teacher or the pupil as a real challenge to pupils capacity to work creatively and independently, but as an exercise in guessing what the teacher wants (Soucek 1995). The possibility that pupils and teachers learn to perform in particular strategic ways as a consequence of performance management (with diminishing returns for real improvement in learning) is one that has been raised by its critics. They argue that people learn how to give a performance: that they focus on those aspects of any task that produces high scores. This may involve teaching to the test or concentrating efforts on meeting the technical requirements of any indicator (for example by producing excellent documentation for inspection or a good portfolio for progression to Chartered Teacher status). The context of international league tables may add to this risk by encouraging nation states to promote

teaching to the test in order to improve their rankings. There are pressures for conformity in the core areas (maths, science and literacy) that may cut across national frameworks and assumptions about teaching and the measurement of performance in these subjects. For example, France withdrew from the OECD sponsored International Adult Literacy Survey (IALS) following poor results. French educationalists argued the design of the survey reflected psychometric practice in the USA which was a function of particular assumptions about how literacy could be categorised and measured. This is just one example of the problems created in using common instruments of measurement that fail to acknowledge the contextual nature of much learning and operate as a crude psychometric steamrollerthat excludes or downweights some components that dont fit its simplistic assumptions (Goldstein 1995:5). The Impact of Performance Management on Teachers and Pupils Reliance on target setting and monitoring as a key element of the management of teachers also raises concerns about the possible distorting effects of targets on relationships between teachers and managers, and on teachers definitions of their core tasks. Teachers, heads and their employers all feel under pressure to demonstrate good performance. This may have positive effects, but it may also reduce trust, inhibit discussion of difficulty and diminish honest self-evaluation at all levels in the system. Because it is necessary to demonstrate constant improvement, teachers, as well as pupils, may experie nce unproductive stress that inhibits their learning and development. Some evidence from a recent study of teachers in Europe and Australia suggests that the performance management approach has had a number of negative consequences for some pupils and teachers. For example, teachers in Portugal, Spain, Finland, Sweden and both Scotland and England reported that they had less time to devote to assisting pupils with difficulties; they had to concentrate on those pupils whose improved performance would count towards achievement of targets. Teachers made the related point that pupils at risk of failure and social exclusion were both more excluded and more aware of their exclusion than previously. Teachers in all the systems in the study noted that the demands of reporting and recording performance, and of managing processes of accountability, had serious impacts on their time and energy (Lindblad and Popkewitz 2001). It is interesting to note that there are concerns about teacher recruitment and retention throughout the developed economies. These concerns may well be connected to the demands made on teachers time by performance management systems. A current OECD investigation of strategies for recruiting and retaining effective

teachers notes that over-prescription of curriculum and assessment may have negative effects for teachers engagement and job satisfaction (OECD 2002). Conclusions Performance management may give a distorted picture of childrens learning in Scottish schools, and may also risk distorting the processes through which they learn. Yet indicators of performance that capture the complexity of childrens learning could be developed, and could play a very important role in promoting social inclusion. Children learn through a complex interaction between what the school provides and the resources that they bring with them but such resources are not equally distributed among pupils. The development of sophisticated indicators could be used to help identify need, to support targeted interventions where they are most required, and to identify and spread effective practice. Further reading Davies, H. Nutley, S. and Smith, P. (eds) What Works? Evidence-based policy and practice in Public Services Bristol: Policy Press. Fitz-Gibbon, CT. (1996) Monitoring Education: Indicators, Quality and Effectiveness, London: Cassell. Goldstein, H. (1995) Interpreting international comparisons of student achievement, Paris: UNESCO. References Goldstein, H. (1998) Models for Reality: new approaches to understanding educational processes (http://www.ioe.ac.uk./hgoldstn/#download). Lindblad, S. and Popkewitz, T. (2001) Education Governance and Social Integration and Exclusion in Europe (Final report of the EGSIE Project), Uppsala: Uppsala University Press. OECD (2002) The Recruitment and Retention of Teachers, Paris: OECD.

Soucek, V. (1995) Flexible Education and new standards of Communicative Competence in J.Kenway (ed) Economising Education: the postfordist directions. Geelong: Deakin University Press. Further information For further details contact Jenny Ozga, CES, email Jenny.Ozga@ed.ac.uk. The views expressed are those of the author.

About this Briefing This Briefing is part of the Knowledge Transfer initiative of the University of Edinburgh, which is funded by the Scottish Higher education Funding Council, with the purpose of making research findings accessible to practitioners and the wider community.

Related CES Briefings

No. 14 League Tables Who Needs Them? by L.Croxford No. 16 Inequality in the First Year of Primary School by L.Croxford No. 19 Inequality in Attainment at Age 16: A Home International Comparison by L.Croxford No. 25 Standards, Inequality and Ability Grouping by A.Gamoran No. 26 Measuring Performance Tackling inequality by L.Croxford All Briefings can be downloaded from our website, free of charge. If hard copy or multiple copies are required please contact Carolyn Newton at the address below. The CES Briefings series is edited by Cathy Howieson (c.howieson@ed.ac.uk). All comments on the Briefings are welcome.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Application Form Session 2017-18: VKNRL School of NursingDokument3 SeitenApplication Form Session 2017-18: VKNRL School of NursingVivekananda Kendra100% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Chandni Kumari PDFDokument2 SeitenChandni Kumari PDFAcsm Acsm AcsmNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Santa Fe Community College 2006-07 CatalogDokument336 SeitenSanta Fe Community College 2006-07 CatalogsfcollegeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Justice Newsletter 2020finalDokument44 SeitenJustice Newsletter 2020finalDannyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Faculty of Built EnvironmentDokument4 SeitenFaculty of Built EnvironmentJessie YeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- MRCP (UK) Regulations October 2023 UpdateDokument18 SeitenMRCP (UK) Regulations October 2023 Updateniamul islamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Re: 1999 Bar Examinations: BM 979 & 986: December 10, 2002: J. Bellosillo: en BancDokument4 SeitenRe: 1999 Bar Examinations: BM 979 & 986: December 10, 2002: J. Bellosillo: en BancJia Chu ChuaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Shivaang Maheshwari - Alternative-Mark-Credit-Allocation-FormDokument2 SeitenShivaang Maheshwari - Alternative-Mark-Credit-Allocation-FormShivaang MaheshwariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- 2nd FILE (Acknowledgement - dedication.docxFINALPAPERDokument10 Seiten2nd FILE (Acknowledgement - dedication.docxFINALPAPERYasmine RamosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- POSITIVISMDokument2 SeitenPOSITIVISMΑικατερίνη Καταπόδη100% (1)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- YogeshDokument6 SeitenYogeshUpadhayayAnkurNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Parts of Speech and Past and PresentDokument8 SeitenParts of Speech and Past and Presentapi-235187700Noch keine Bewertungen

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Sche - Ap.gov - in EAMCET Eamcet EAMCET DownloadHallTicketLive2017Dokument4 SeitenSche - Ap.gov - in EAMCET Eamcet EAMCET DownloadHallTicketLive2017mrlrdy1321Noch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- 2017 Imo Level 1 Sample Paper Class-4Dokument5 Seiten2017 Imo Level 1 Sample Paper Class-4jkguru75100% (2)

- LAC Session 4 Understanding Learners' Mulitiple Intelligences 2Dokument3 SeitenLAC Session 4 Understanding Learners' Mulitiple Intelligences 2Gracel Alingod GalayNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- BLESSINGSDokument38 SeitenBLESSINGSleo simporiosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Student Application Form: Personal DetailsDokument3 SeitenStudent Application Form: Personal DetailsDickson IsaguirreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Official Notification For TSNPDCL RecruitmentDokument16 SeitenOfficial Notification For TSNPDCL RecruitmentSupriya SantreNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Lesson Plans 4Dokument1 SeiteLesson Plans 4api-368156036Noch keine Bewertungen

- SJT Practice - Free SampleDokument3 SeitenSJT Practice - Free SampleGabor SzucsNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Scie Method Lesson 4Dokument8 SeitenScie Method Lesson 4vicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Course Outline GCWorldDokument3 SeitenCourse Outline GCWorldJaylord VerazonNoch keine Bewertungen

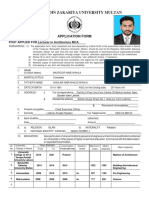

- Bahauddin Zakariya University Multan: Application FormDokument4 SeitenBahauddin Zakariya University Multan: Application FormzakiakbarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Annotated BibliographyDokument17 SeitenAnnotated BibliographylawNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Nova SBE Handbook Students General InformationDokument32 SeitenNova SBE Handbook Students General InformationVasco TamenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Application For Migration CertificateDokument2 SeitenApplication For Migration CertificateRohit SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Test Answer Key: UnitsDokument1 SeiteTest Answer Key: UnitsPaul Sebastian100% (2)

- How To Respond To Extended Response Questions Global Strategy and Leadership - S1 2019Dokument11 SeitenHow To Respond To Extended Response Questions Global Strategy and Leadership - S1 2019kennyeffectNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Learned Helplessness of HumansDokument26 SeitenLearned Helplessness of HumansSaumya Sharma100% (1)

- Common Abbreviations & Acronyms Used in Education Acronym Definition AADokument8 SeitenCommon Abbreviations & Acronyms Used in Education Acronym Definition AASarigta Ku KadnantanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)