Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Corruption

Hochgeladen von

Chandan KumarOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Corruption

Hochgeladen von

Chandan KumarCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Corruption, Politics and Democracy

For centuries saints and sages have urged the people to eliminate graft and corruption from private as well as public life; there have been countless sermons against this deep-rooted menace that has eaten into the vitals of society, distorted all values and made mincemeat of morality, truth and virtue. But the evil has grown to gigantic proportions and there is hardly any sphere of social, economic, political and even religious activity that is free from graft, deception and corruption of some kind. Like the air we breathe, it has become all-pervasive and entered every aspect of life to such an extent that it is now regarded as a fact of life and an evil we have to live with. In fact, a time has come when very few eyebrows are raised when we are informed of a case of blatant bribery; it is so common, so usual and all too familiar. We give and take bribes in the sphere of education, government and private service, all branches of administration, trade and commerce, industrial activity; scrupulous honesty is rare; even temples and other places of worship are not free of it. Most of our politicians and legislators indulge in it without any qualms of conscience. Corruption has continued, and even increased beyond measure, even as democracy has spread and civilization has advanced; so it can no longer be asserted that democracy and corruption are incompatible; both are developing fast, and simultaneously, and as far as human vision can go this duality will continue. Chanakya, the Machiavelli of India and the celebrated author of Arthashastra (which has been described as the manual of government in the times of the Mauryas), specifically mentions 40 types of ways of embezzling government property. It is true, however, that the opportunities for bribery and palm-greasing have increased greatly with the dawn of Independence, and the growth of democracy and industry, the system of licenses and permits for setting up enterprises, securing quotas of raw materials, imports and exports and expansion of trade and commerce. Consequently, the types of corruption have increased a thousand fold; the panorama is vast and baffling and beyond control however loud the talk of anti-corruption measures, stringent laws and of deterrent sentences. Every few years there is much discussion of this problem which is described as the foremost issue in the country; corruption is condemned as a cancer in society, but then there is silence; the flush of enthusiasm fades away and life goes on in the same way. The focus of attention shifts to other more pressing problems of bread and butter and of politico survival; of new ministers and new parties and politicians, of enquiries and commissions and political witch-hunting, of majorities and minorities in Parliament and State legislatures. The problem is indeed difficult and delicate. Ministers are the leaders of the political party which, by virtue of being in a majority or a partner in a coalition set-up, constitute the government. Lokpal, who would have the authority to enquire into allegations against a Central minister or his secretary and others. Every man, it is said, has his price, and by and large this has proved true. When the entire social and economic set-up breathes of what is called "speed money" to push things through, it is almost impossible to resist temptationhuman beings are, after all, human beings. But the stink lies not only in the prevalence of the lure of gold, but in the hypocrisy that accompanies it.Even

after having accepted bribes the corrupt person talks the very next day of high moral standards and urges people from public platforms to follow Mahatma Gandhi's principles and be honest and pure and zealously, serve the nation. Such hypocrisy compounds the offence, but our ministers, politicians and officials are getting thick-skinned; it is all a way of life, a routine, and hence may be described as unavoidable and a disease that is incurable. After all, when there is graft, deception and bribery, on a small or big scale at every stepin the administration, in the educational sphere, in legislatures and even, it is believed, in religious institutionswhat is the relatively honest person to do but to fall in line? Don't we also bribe the gods with gifts of all sorts, so-runs another argument. Promises and oaths of honesty are soon forgotten, and the norms return again. These norms are palm-greasing, extortions by politicians from industrialists, by inspectors from shopkeepers, by officials and clerks from the public and by everybody from everybody else, even for small favours. The vicious circle remains.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Midland Spread1Dokument14 SeitenMidland Spread1Chandan KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- CorruptionDokument2 SeitenCorruptionChandan KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quest Inn A Ire 1Dokument4 SeitenQuest Inn A Ire 1Chandan KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Job Crafting - DuttonDokument23 SeitenJob Crafting - DuttonChandan KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Job Crafting - DuttonDokument23 SeitenJob Crafting - DuttonChandan KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Demographic Study For Consumer Product (Laptop) Evaluation Based On Add-On FeaturesDokument18 SeitenDemographic Study For Consumer Product (Laptop) Evaluation Based On Add-On Featureschayan83Noch keine Bewertungen

- Absorption and Marginal CostingDokument58 SeitenAbsorption and Marginal Costingjack0826Noch keine Bewertungen

- Excel Tutorial OriginalDokument381 SeitenExcel Tutorial OriginalChandan Kumar100% (1)

- myengg/wbjee/AIEEE Closing Rank 2010Dokument15 Seitenmyengg/wbjee/AIEEE Closing Rank 2010Lokesh Kumar100% (1)

- Job Crafting - DuttonDokument23 SeitenJob Crafting - DuttonChandan KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Formula Sheet v1.1Dokument12 SeitenFormula Sheet v1.1fabian_moaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Bank Branch List For The Website Sl. No. Branch Name Branch IDDokument10 SeitenBank Branch List For The Website Sl. No. Branch Name Branch IDmayankgalwarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit Plan RevisedDokument13 SeitenUnit Plan Revisedapi-396407573Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Truth in Lending Act and The Equal Credit Opportunity ActDokument5 SeitenThe Truth in Lending Act and The Equal Credit Opportunity ActMercy LingatingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maramba Vs LozanoDokument2 SeitenMaramba Vs LozanoWendell Leigh Oasan100% (3)

- Lay Judge JanuaryDokument331 SeitenLay Judge Januaryjmanu9997Noch keine Bewertungen

- FIFA Trial Form - ENDokument5 SeitenFIFA Trial Form - ENUtkarshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 9 Global Interstate System IntroductionDokument52 SeitenLesson 9 Global Interstate System IntroductionAngelyn MortelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 2 Vocabulary TestDokument3 SeitenUnit 2 Vocabulary TestJill JacobsNoch keine Bewertungen

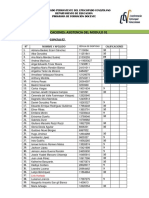

- Calificaciones: Asistencia Del Modulo 01 Docente: Profesor. Henry GonzalezDokument2 SeitenCalificaciones: Asistencia Del Modulo 01 Docente: Profesor. Henry Gonzalezadriana ecarriNoch keine Bewertungen

- My Impression of The Catholic Church TodayDokument3 SeitenMy Impression of The Catholic Church TodayRomrom LabocNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conditionals Type 0 1 2Dokument4 SeitenConditionals Type 0 1 2Ivana PlenčaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scott Pearce's Master Essay Method Constitutional LawDokument32 SeitenScott Pearce's Master Essay Method Constitutional LawStacy OliveiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- LawDokument12 SeitenLawUdit SabooNoch keine Bewertungen

- 23rd Moot CaseDokument22 Seiten23rd Moot CaseYogender YadavNoch keine Bewertungen

- G.R. No. 179150 June 17, 2008 PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, DELIA BAYANI y BOTANES, Accused-Appellant. Decision Chico-Nazario, J.Dokument10 SeitenG.R. No. 179150 June 17, 2008 PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, DELIA BAYANI y BOTANES, Accused-Appellant. Decision Chico-Nazario, J.Meg VillaricaNoch keine Bewertungen

- White ChristmasDokument7 SeitenWhite ChristmasSara RaesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Israel Tour 2014 With Nigel & Rochelle MerrickDokument20 SeitenIsrael Tour 2014 With Nigel & Rochelle MerrickInnerFaithTravelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maurice Bucaille's InspiringDokument2 SeitenMaurice Bucaille's Inspiringsonu24meNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3 Circular NR 17, DND, Afp DTD 02 October 1987, Subject Administrative Discharge Prior To Expiration of Term of EnlistmentDokument12 Seiten3 Circular NR 17, DND, Afp DTD 02 October 1987, Subject Administrative Discharge Prior To Expiration of Term of EnlistmentCHRIS ALAMATNoch keine Bewertungen

- J 2012 3 GNLU L Rev April 17 Suchitrasheoran Rgnulacin 20201215 101546 1 11 PDFDokument11 SeitenJ 2012 3 GNLU L Rev April 17 Suchitrasheoran Rgnulacin 20201215 101546 1 11 PDF16123 SUCHITRA SHEORANNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nitto Enterprises vs. NLRCDokument4 SeitenNitto Enterprises vs. NLRCKrisia OrenseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Political Law Syllabus-Based CodalDokument19 SeitenPolitical Law Syllabus-Based CodalAlthea Angela GarciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Family PlanningDokument13 SeitenFamily PlanningYana PotNoch keine Bewertungen

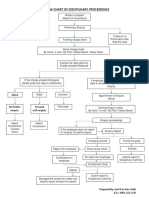

- Grievance Redressal Flow ChartDokument1 SeiteGrievance Redressal Flow ChartAmit PaulNoch keine Bewertungen

- Instant Download Health Behavior Theory Research and Practice Jossey Bass Public Health PDF FREEDokument32 SeitenInstant Download Health Behavior Theory Research and Practice Jossey Bass Public Health PDF FREEjeremy.bryant531100% (46)

- RODRIGO RIVERA vs. SPOUSES SALVADOR CHUA AND VIOLETA S. CHUADokument2 SeitenRODRIGO RIVERA vs. SPOUSES SALVADOR CHUA AND VIOLETA S. CHUAIvy Clarize Amisola BernardezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Child Abuse - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia PDFDokument26 SeitenChild Abuse - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia PDFBrar BrarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hacking Getting CreditDokument6 SeitenHacking Getting Creditsayyed Ayman73% (11)

- IARYCZOWER ET AL. - Judicial Independence in Unstable Environments, Argentina 1935-1998Dokument19 SeitenIARYCZOWER ET AL. - Judicial Independence in Unstable Environments, Argentina 1935-1998Daniel GOMEZNoch keine Bewertungen

- In Re Burger Boys, Inc., Debtor. South Street Seaport Limited Partnership, Creditor-Appellant v. Burger Boys, Inc., Doing Business as Burger Boys of Brooklyn, Debtor-Appellee, 94 F.3d 755, 2d Cir. (1996)Dokument11 SeitenIn Re Burger Boys, Inc., Debtor. South Street Seaport Limited Partnership, Creditor-Appellant v. Burger Boys, Inc., Doing Business as Burger Boys of Brooklyn, Debtor-Appellee, 94 F.3d 755, 2d Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen