Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Nego Assgn 5

Hochgeladen von

Carmina May ManaloOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Nego Assgn 5

Hochgeladen von

Carmina May ManaloCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Republic of the Philippines SUPREME COURT Manila EN BANC G.R. No.

L-15126 November 30, 1961

VICENTE R. DE OCAMPO & CO., plaintiff-appellee, vs. ANITA GATCHALIAN, ET AL., defendants-appellants. Vicente Formoso, Jr. for plaintiff-appellee. Reyes and Pangalagan for defendants-appellants. LABRADOR, J.: Appeal from a judgment of the Court of First Instance of Manila, Hon. Conrado M. Velasquez, presiding, sentencing the defendants to pay the plaintiff the sum of P600, with legal interest from September 10, 1953 until paid, and to pay the costs. The action is for the recovery of the value of a check for P600 payable to the plaintiff and drawn by defendant Anita C. Gatchalian. The complaint sets forth the check and alleges that plaintiff received it in payment of the indebtedness of one Matilde Gonzales; that upon receipt of said check, plaintiff gave Matilde Gonzales P158.25, the difference between the face value of the check and Matilde Gonzales' indebtedness. The defendants admit the execution of the check but they allege in their answer, as affirmative defense, that it was issued subject to a condition, which was not fulfilled, and that plaintiff was guilty of gross negligence in not taking steps to protect itself. At the time of the trial, the parties submitted a stipulation of facts, which reads as follows: Plaintiff and defendants through their respective undersigned attorney's respectfully submit the following Agreed Stipulation of Facts; First. That on or about 8 September 1953, in the evening, defendant Anita C. Gatchalian who was then interested in looking for a car for the use of her husband and the family, was shown and offered a car by Manuel Gonzales who was accompanied by Emil Fajardo, the latter being personally known to defendant Anita C. Gatchalian; Second. That Manuel Gonzales represented to defend Anita C. Gatchalian that he was duly authorized by the owner of the car, Ocampo Clinic, to look for a buyer of said car and to negotiate for and accomplish said sale, but which facts were not known to plaintiff;

Third. That defendant Anita C. Gatchalian, finding the price of the car quoted by Manuel Gonzales to her satisfaction, requested Manuel Gonzales to bring the car the day following together with the certificate of registration of the car, so that her husband would be able to see same; that on this request of defendant Anita C. Gatchalian, Manuel Gonzales advised her that the owner of the car will not be willing to give the certificate of registration unless there is a showing that the party interested in the purchase of said car is ready and willing to make such purchase and that for this purpose Manuel Gonzales requested defendant Anita C. Gatchalian to give him (Manuel Gonzales) a check which will be shown to the owner as evidence of buyer's good faith in the intention to purchase the said car, the said check to be for safekeeping only of Manuel Gonzales and to be returned to defendant Anita C. Gatchalian the following day when Manuel Gonzales brings the car and the certificate of registration, but which facts were not known to plaintiff; Fourth. That relying on these representations of Manuel Gonzales and with his assurance that said check will be only for safekeeping and which will be returned to said defendant the following day when the car and its certificate of registration will be brought by Manuel Gonzales to defendants, but which facts were not known to plaintiff, defendant Anita C. Gatchalian drew and issued a check, Exh. "B"; that Manuel Gonzales executed and issued a receipt for said check, Exh. "1"; Fifth. That on the failure of Manuel Gonzales to appear the day following and on his failure to bring the car and its certificate of registration and to return the check, Exh. "B", on the following day as previously agreed upon, defendant Anita C. Gatchalian issued a "Stop Payment Order" on the check, Exh. "3", with the drawee bank. Said "Stop Payment Order" was issued without previous notice on plaintiff not being know to defendant, Anita C. Gatchalian and who furthermore had no reason to know check was given to plaintiff; Sixth. That defendants, both or either of them, did not know personally Manuel Gonzales or any member of his family at any time prior to September 1953, but that defendant Hipolito Gatchalian is personally acquainted with V. R. de Ocampo; Seventh. That defendants, both or either of them, had no arrangements or agreement with the Ocampo Clinic at any time prior to, on or after 9 September 1953 for the hospitalization of the wife of Manuel Gonzales and neither or both of said defendants had assumed, expressly or impliedly, with the Ocampo Clinic, the obligation of Manuel Gonzales or his wife for the hospitalization of the latter; Eight. That defendants, both or either of them, had no obligation or liability, directly or indirectly with the Ocampo Clinic before, or on 9 September 1953;

Ninth. That Manuel Gonzales having received the check Exh. "B" from defendant Anita C. Gatchalian under the representations and conditions herein above specified, delivered the same to the Ocampo Clinic, in payment of the fees and expenses arising from the hospitalization of his wife; Tenth. That plaintiff for and in consideration of fees and expenses of hospitalization and the release of the wife of Manuel Gonzales from its hospital, accepted said check, applying P441.75 (Exhibit "A") thereof to payment of said fees and expenses and delivering to Manuel Gonzales the amount of P158.25 (as per receipt, Exhibit "D") representing the balance on the amount of the said check, Exh. "B"; Eleventh. That the acts of acceptance of the check and application of its proceeds in the manner specified above were made without previous inquiry by plaintiff from defendants: Twelfth. That plaintiff filed or caused to be filed with the Office of the City Fiscal of Manila, a complaint for estafa against Manuel Gonzales based on and arising from the acts of said Manuel Gonzales in paying his obligations with plaintiff and receiving the cash balance of the check, Exh. "B" and that said complaint was subsequently dropped; Thirteenth. That the exhibits mentioned in this stipulation and the other exhibits submitted previously, be considered as parts of this stipulation, without necessity of formally offering them in evidence; WHEREFORE, it is most respectfully prayed that this agreed stipulation of facts be admitted and that the parties hereto be given fifteen days from today within which to submit simultaneously their memorandum to discuss the issues of law arising from the facts, reserving to either party the right to submit reply memorandum, if necessary, within ten days from receipt of their main memoranda. (pp. 21-25, Defendant's Record on Appeal). No other evidence was submitted and upon said stipulation the court rendered the judgment already alluded above. In their appeal defendants-appellants contend that the check is not a negotiable instrument, under the facts and circumstances stated in the stipulation of facts, and that plaintiff is not a holder in due course. In support of the first contention, it is argued that defendant Gatchalian had no intention to transfer her property in the instrument as it was for safekeeping merely and, therefore, there was no delivery required by law (Section 16, Negotiable Instruments Law); that assuming for the sake of argument that delivery was not for safekeeping merely, delivery was conditional and the condition was not fulfilled.

In support of the contention that plaintiff-appellee is not a holder in due course, the appellant argues that plaintiff-appellee cannot be a holder in due course because there was no negotiation prior to plaintiff-appellee's acquiring the possession of the check; that a holder in due course presupposes a prior party from whose hands negotiation proceeded, and in the case at bar, plaintiff-appellee is the payee, the maker and the payee being original parties. It is also claimed that the plaintiff-appellee is not a holder in due course because it acquired the check with notice of defect in the title of the holder, Manuel Gonzales, and because under the circumstances stated in the stipulation of facts there were circumstances that brought suspicion about Gonzales' possession and negotiation, which circumstances should have placed the plaintiff-appellee under the duty, to inquire into the title of the holder. The circumstances are as follows: The check is not a personal check of Manuel Gonzales. (Paragraph Ninth, Stipulation of Facts). Plaintiff could have inquired why a person would use the check of another to pay his own debt. Furthermore, plaintiff had the "means of knowledge" inasmuch as defendant Hipolito Gatchalian is personally acquainted with V. R. de Ocampo (Paragraph Sixth, Stipulation of Facts.). The maker Anita C. Gatchalian is a complete stranger to Manuel Gonzales and Dr. V. R. de Ocampo (Paragraph Sixth, Stipulation of Facts). The maker is not in any manner obligated to Ocampo Clinic nor to Manuel Gonzales. (Par. 7, Stipulation of Facts.) The check could not have been intended to pay the hospital fees which amounted only to P441.75. The check is in the amount of P600.00, which is in excess of the amount due plaintiff. (Par. 10, Stipulation of Facts). It was necessary for plaintiff to give Manuel Gonzales change in the sum P158.25 (Par. 10, Stipulation of Facts). Since Manuel Gonzales is the party obliged to pay, plaintiff should have been more cautious and wary in accepting a piece of paper and disbursing cold cash. The check is payable to bearer. Hence, any person who holds it should have been subjected to inquiries. EVEN IN A BANK, CHECKS ARE NOT CASHED WITHOUT INQUIRY FROM THE BEARER. The same inquiries should have been made by plaintiff. (Defendants-appellants' brief, pp. 52-53) Answering the first contention of appellant, counsel for plaintiff-appellee argues that in accordance with the best authority on the Negotiable Instruments Law, plaintiff-appellee may be considered as a holder in due course, citing Brannan's Negotiable Instruments Law, 6th edition, page 252. On this issue Brannan holds that a payee may be a holder in due course and says that to this effect is the greater weight of authority, thus: Whether the payee may be a holder in due course under the N. I. L., as he was at common law, is a question upon which the courts are in serious conflict. There

can be no doubt that a proper interpretation of the act read as a whole leads to the conclusion that a payee may be a holder in due course under any circumstance in which he meets the requirements of Sec. 52. The argument of Professor Brannan in an earlier edition of this work has never been successfully answered and is here repeated. Section 191 defines "holder" as the payee or indorsee of a bill or note, who is in possession of it, or the bearer thereof. Sec. 52 defendants defines a holder in due course as "a holder who has taken the instrument under the following conditions: 1. That it is complete and regular on its face. 2. That he became the holder of it before it was overdue, and without notice that it had been previously dishonored, if such was the fact. 3. That he took it in good faith and for value. 4. That at the time it was negotiated to him he had no notice of any infirmity in the instrument or defect in the title of the person negotiating it." Since "holder", as defined in sec. 191, includes a payee who is in possession the word holder in the first clause of sec. 52 and in the second subsection may be replaced by the definition in sec. 191 so as to read "a holder in due course is a payee or indorsee who is in possession," etc. (Brannan's on Negotiable Instruments Law, 6th ed., p. 543). The first argument of the defendants-appellants, therefore, depends upon whether or not the plaintiff-appellee is a holder in due course. If it is such a holder in due course, it is immaterial that it was the payee and an immediate party to the instrument. The other contention of the plaintiff is that there has been no negotiation of the instrument, because the drawer did not deliver the instrument to Manuel Gonzales with the intention of negotiating the same, or for the purpose of giving effect thereto, for as the stipulation of facts declares the check was to remain in the possession Manuel Gonzales, and was not to be negotiated, but was to serve merely as evidence of good faith of defendants in their desire to purchase the car being sold to them. Admitting that such was the intention of the drawer of the check when she delivered it to Manuel Gonzales, it was no fault of the plaintiff-appellee drawee if Manuel Gonzales delivered the check or negotiated it. As the check was payable to the plaintiff-appellee, and was entrusted to Manuel Gonzales by Gatchalian, the delivery to Manuel Gonzales was a delivery by the drawer to his own agent; in other words, Manuel Gonzales was the agent of the drawer Anita Gatchalian insofar as the possession of the check is concerned. So, when the agent of drawer Manuel Gonzales negotiated the check with the intention of getting its value from plaintiff-appellee, negotiation took place through no fault of the plaintiff-appellee, unless it can be shown that the plaintiff-appellee should be considered as having notice of the defect in the possession of the holder Manuel Gonzales. Our resolution of this issue leads us to a consideration of the last question presented by the appellants, i.e., whether the plaintiff-appellee may be considered as a holder in due course.

Section 52, Negotiable Instruments Law, defines holder in due course, thus: A holder in due course is a holder who has taken the instrument under the following conditions: (a) That it is complete and regular upon its face; (b) That he became the holder of it before it was overdue, and without notice that it had been previously dishonored, if such was the fact; (c) That he took it in good faith and for value; (d) That at the time it was negotiated to him he had no notice of any infirmity in the instrument or defect in the title of the person negotiating it. The stipulation of facts expressly states that plaintiff-appellee was not aware of the circumstances under which the check was delivered to Manuel Gonzales, but we agree with the defendants-appellants that the circumstances indicated by them in their briefs, such as the fact that appellants had no obligation or liability to the Ocampo Clinic; that the amount of the check did not correspond exactly with the obligation of Matilde Gonzales to Dr. V. R. de Ocampo; and that the check had two parallel lines in the upper left hand corner, which practice means that the check could only be deposited but may not be converted into cash all these circumstances should have put the plaintiffappellee to inquiry as to the why and wherefore of the possession of the check by Manuel Gonzales, and why he used it to pay Matilde's account. It was payee's duty to ascertain from the holder Manuel Gonzales what the nature of the latter's title to the check was or the nature of his possession. Having failed in this respect, we must declare that plaintiff-appellee was guilty of gross neglect in not finding out the nature of the title and possession of Manuel Gonzales, amounting to legal absence of good faith, and it may not be considered as a holder of the check in good faith. To such effect is the consensus of authority. In order to show that the defendant had "knowledge of such facts that his action in taking the instrument amounted to bad faith," it is not necessary to prove that the defendant knew the exact fraud that was practiced upon the plaintiff by the defendant's assignor, it being sufficient to show that the defendant had notice that there was something wrong about his assignor's acquisition of title, although he did not have notice of the particular wrong that was committed. Paika v. Perry, 225 Mass. 563, 114 N.E. 830. It is sufficient that the buyer of a note had notice or knowledge that the note was in some way tainted with fraud. It is not necessary that he should know the particulars or even the nature of the fraud, since all that is required is knowledge of such facts that his action in taking the note amounted bad faith. Ozark Motor Co. v. Horton (Mo. App.), 196 S.W. 395. Accord. Davis v. First Nat. Bank, 26 Ariz. 621, 229 Pac. 391.

Liberty bonds stolen from the plaintiff were brought by the thief, a boy fifteen years old, less than five feet tall, immature in appearance and bearing on his face the stamp a degenerate, to the defendants' clerk for sale. The boy stated that they belonged to his mother. The defendants paid the boy for the bonds without any further inquiry. Held, the plaintiff could recover the value of the bonds. The term 'bad faith' does not necessarily involve furtive motives, but means bad faith in a commercial sense. The manner in which the defendants conducted their Liberty Loan department provided an easy way for thieves to dispose of their plunder. It was a case of "no questions asked." Although gross negligence does not of itself constitute bad faith, it is evidence from which bad faith may be inferred. The circumstances thrust the duty upon the defendants to make further inquiries and they had no right to shut their eyes deliberately to obvious facts. Morris v. Muir, 111 Misc. Rep. 739, 181 N.Y. Supp. 913, affd. in memo., 191 App. Div. 947, 181 N.Y. Supp. 945." (pp. 640-642, Brannan's Negotiable Instruments Law, 6th ed.). The above considerations would seem sufficient to justify our ruling that plaintiffappellee should not be allowed to recover the value of the check. Let us now examine the express provisions of the Negotiable Instruments Law pertinent to the matter to find if our ruling conforms thereto. Section 52 (c) provides that a holder in due course is one who takes the instrument "in good faith and for value;" Section 59, "that every holder is deemed prima facie to be a holder in due course;" and Section 52 (d), that in order that one may be a holder in due course it is necessary that "at the time the instrument was negotiated to him "he had no notice of any . . . defect in the title of the person negotiating it;" and lastly Section 59, that every holder is deemed prima facieto be a holder in due course. In the case at bar the rule that a possessor of the instrument is prima faciea holder in due course does not apply because there was a defect in the title of the holder (Manuel Gonzales), because the instrument is not payable to him or to bearer. On the other hand, the stipulation of facts indicated by the appellants in their brief, like the fact that the drawer had no account with the payee; that the holder did not show or tell the payee why he had the check in his possession and why he was using it for the payment of his own personal account show that holder's title was defective or suspicious, to say the least. As holder's title was defective or suspicious, it cannot be stated that the payee acquired the check without knowledge of said defect in holder's title, and for this reason the presumption that it is a holder in due course or that it acquired the instrument in good faith does not exist. And having presented no evidence that it acquired the check in good faith, it (payee) cannot be considered as a holder in due course. In other words, under the circumstances of the case, instead of the presumption that payee was a holder in good faith, the fact is that it acquired possession of the instrument under circumstances that should have put it to inquiry as to the title of the holder who negotiated the check to it. The burden was, therefore, placed upon it to show that notwithstanding the suspicious circumstances, it acquired the check in actual good faith.

The rule applicable to the case at bar is that described in the case of Howard National Bank v. Wilson, et al., 96 Vt. 438, 120 At. 889, 894, where the Supreme Court of Vermont made the following disquisition: Prior to the Negotiable Instruments Act, two distinct lines of cases had developed in this country. The first had its origin in Gill v. Cubitt, 3 B. & C. 466, 10 E. L. 215, where the rule was distinctly laid down by the court of King's Bench that the purchaser of negotiable paper must exercise reasonable prudence and caution, and that, if the circumstances were such as ought to have excited the suspicion of a prudent and careful man, and he made no inquiry, he did not stand in the legal position of a bona fide holder. The rule was adopted by the courts of this country generally and seem to have become a fixed rule in the law of negotiable paper. Later in Goodman v. Harvey, 4 A. & E. 870, 31 E. C. L. 381, the English court abandoned its former position and adopted the rule that nothing short of actual bad faith or fraud in the purchaser would deprive him of the character of a bona fide purchaser and let in defenses existing between prior parties, that no circumstances of suspicion merely, or want of proper caution in the purchaser, would have this effect, and that even gross negligence would have no effect, except as evidence tending to establish bad faith or fraud. Some of the American courts adhered to the earlier rule, while others followed the change inaugurated in Goodman v. Harvey. The question was before this court in Roth v. Colvin, 32 Vt. 125, and, on full consideration of the question, a rule was adopted in harmony with that announced in Gill v. Cubitt, which has been adhered to in subsequent cases, including those cited above. Stated briefly, one line of cases including our own had adopted the test of the reasonably prudent man and the other that of actual good faith. It would seem that it was the intent of the Negotiable Instruments Act to harmonize this disagreement by adopting the latter test. That such is the view generally accepted by the courts appears from a recent review of the cases concerning what constitutes notice of defect. Brannan on Neg. Ins. Law, 187-201. To effectuate the general purpose of the act to make uniform the Negotiable Instruments Law of those states which should enact it, we are constrained to hold (contrary to the rule adopted in our former decisions) that negligence on the part of the plaintiff, or suspicious circumstances sufficient to put a prudent man on inquiry, will not of themselves prevent a recovery, but are to be considered merely as evidence bearing on the question of bad faith. See G. L. 3113, 3172, where such a course is required in construing other uniform acts. It comes to this then: When the case has taken such shape that the plaintiff is called upon to prove himself a holder in due course to be entitled to recover, he is required to establish the conditions entitling him to standing as such, including good faith in taking the instrument. It devolves upon him to disclose the facts and circumstances attending the transfer, from which good or bad faith in the transaction may be inferred. In the case at bar as the payee acquired the check under circumstances which should have put it to inquiry, why the holder had the check and used it to pay his own personal

account, the duty devolved upon it, plaintiff-appellee, to prove that it actually acquired said check in good faith. The stipulation of facts contains no statement of such good faith, hence we are forced to the conclusion that plaintiff payee has not proved that it acquired the check in good faith and may not be deemed a holder in due course thereof. For the foregoing considerations, the decision appealed from should be, as it is hereby, reversed, and the defendants are absolved from the complaint. With costs against plaintiff-appellee. Padilla, Bautista Angelo, Concepcion, Reyes, J.B.L., Barrera, Paredes, Dizon and De Leon, JJ., concur. Bengzon, C.J., concurs in the result.

The Lawphil Project - Arellano Law Foundation De Ocampo vs. Gatchalian (3 SCRA 596) Post under case digests, Commercial Law at Wednesday, February 08, 2012 Posted by Schizophrenic Mind Facts: Anita Gatchalian was interested in buying a car when she was offered by Manuel Gonzales to a car owned by the OcampoClinic. Gonzales claim that he was duly authorized to look for a buyer, negotiate and accomplish the sale by the Ocampo Clinic. Anita accepted the offer and insisted to deliver the car with the certificate of registration the next day but Gonzales advised that the owners would only comply only upon showing of interest on the part of the buyer. Gonzales recommended issuing a check (P600 / payable-to-bearer /cross-checked) as evidence of the buyers good faith. Gonzales added that it will only be for safekeeping and will be returned to her the following day.

The next day, Gonzales never appeared. The failure of Gonzales to appeal resulted in Gatchalian to issue a STOP PAYMENT ORDER on the check. It was later found out that Gonzales used the check as payment to the Vicente de Ocampo (Ocampo Clinic) for the hospitalization fees of his wife (the fees were only P441.75, so he got a refund of P158.25). De Ocampo now demands payment for the check, which Gatchalian refused, arguing that de Ocampo is not a holder in due course and that there is no negotiation of the check.

The Court of First Instance ordered Gatchalian to pay the amount of the check to

De Ocampo. Issue: Whether or not

Hence De Ocampo is a

this holder in due

case. course.

Held: NO. De Ocampo is not a holder in due course. De Ocampo was negligent in his acquisition of the check. There were many instances that arouse suspicion: the drawer in the check (Gatchalian) has no liability with de Ocampo ; it was cross-checked(only for deposit) but was used a payment by Gonzales; it was not the exact amount of the medical fees. The circumstances should have led him to inquire on the validity of the check. In However, showing a he failed person to exercise reasonable had knowledge prudence of facts and caution. his

that

action in taking the instrument amounted to bad faith need not prove that he knows the exact fraud. It is sufficient to show that the person had NOTICE that there was something wrong. The bad faith here means bad faith in the commercial sense obtaining an instrument with no questions asked or no further inquiry upon suspicion. The presumption of good faith did not apply to de Ocampo because the defect was apparent on the instruments face it was not payable to Gonzales or bearer. Hence, the holders title is defective or suspicious. Being the case, de Ocampo had the burden of provinghe was a holder in due course, but failed.

Republic of the Philippines SUPREME COURT Manila SECOND DIVISION G.R. No. 70145 November 13, 1986 MARCELO A. MESINA, petitioner, vs. THE HONORABLE INTERMEDIATE APPELLATE COURT, HON. ARSENIO M. GONONG, in his capacity as Judge of Regional Trial Court Manila (Branch VIII), JOSE GO, and ALBERT UY, respondents.

PARAS, J.: This is an appeal by certiorari from the decision of the then Intermediate Appellate Court (IAC for short), now the Court of Appeals (CA) in AC-G.R. S.P. 04710, dated Jan. 22, 1985, which dismissed the petition for certiorari and prohibition filed by Marcelo A. Mesina against the trial court in Civil Case No. 84-22515. Said case (an Interpleader) was filed by Associated Bank against Jose Go and Marcelo A. Mesina regarding their conflicting claims over Associated Bank Cashier's Check No. 011302 for P800,000.00, dated December 29, 1983. Briefly, the facts and statement of the case are as follows: Respondent Jose Go, on December 29, 1983, purchased from Associated Bank Cashier's Check No. 011302 for P800,000.00. Unfortunately, Jose Go left said check on the top of the desk of the bank manager when he left the bank. The bank manager entrusted the check for safekeeping to a bank official, a certain Albert Uy, who had then a visitor in the person of Alexander Lim. Uy had to answer a phone call on a nearby telephone after which he proceeded to the men's room. When he returned to his desk, his visitor Lim was already gone. When Jose Go inquired for his cashier's check from Albert Uy, the check was not in his folder and nowhere to be found. The latter advised Jose Go to go to the bank to accomplish a "STOP PAYMENT" order, which suggestion Jose Go immediately followed. He also executed an affidavit of loss. Albert Uy went to the police to report the loss of the check, pointing to the person of Alexander Lim as the one who could shed light on it. The records of the police show that Associated Bank received the lost check for clearing on December 31, 1983, coming from Prudential Bank, Escolta Branch. The check was immediately dishonored by Associated Bank by sending it back to Prudential Bank, with the words "Payment Stopped" stamped on it. However, the same was again returned to Associated Bank on January 4, 1984 and for the second time it was dishonored. Several days later, respondent Associated Bank received a letter, dated January 9, 1984, from a certain Atty. Lorenzo Navarro demanding payment on the cashier's check in question, which was being held by his client. He however refused to reveal the name of his client and threatened to sue, if payment is not made. Respondent bank, in its letter, dated January 20, 1984, replied saying the check belonged to Jose Go who lost it in the bank and is laying claim to it. On February 1, 1984, police sent a letter to the Manager of the Prudential Bank, Escolta Branch, requesting assistance in Identifying the person who tried to encash the check but said bank refused saying that it had to protect its client's interest and the Identity could only be revealed with the client's conformity. Unsure of what to do on the matter, respondent Associated Bank on February 2, 1984 filed an action for Interpleader naming as respondent, Jose Go and one John Doe, Atty. Navarro's then unnamed client. On even date, respondent bank received summons and copy of the complaint for damages of a certain Marcelo A. Mesina from the Regional Trial Court (RTC) of Caloocan City filed on January 23, 1984 bearing the number C-11139. Respondent

bank moved to amend its complaint, having been notified for the first time of the name of Atty. Navarro's client and substituted Marcelo A. Mesina for John Doe. Simultaneously, respondent bank, thru representative Albert Uy, informed Cpl. Gimao of the Western Police District that the lost check of Jose Go is in the possession of Marcelo Mesina, herein petitioner. When Cpl. Gimao went to Marcelo Mesina to ask how he came to possess the check, he said it was paid to him by Alexander Lim in a "certain transaction" but refused to elucidate further. An information for theft (Annex J) was instituted against Alexander Lim and the corresponding warrant for his arrest was issued (Annex 6-A) which up to the date of the filing of this instant petition remains unserved because of Alexander Lim's successful evation thereof. Meanwhile, Jose Go filed his answer on February 24, 1984 in the Interpleader Case and moved to participate as intervenor in the complain for damages. Albert Uy filed a motion of intervention and answer in the complaint for Interpleader. On the Scheduled date of pretrial conference inthe interpleader case, it was disclosed that the "John Doe" impleaded as one of the defendants is actually petitioner Marcelo A. Mesina. Petitioner instead of filing his answer to the complaint in the interpleader filed on May 17, 1984 an Omnibus Motion to Dismiss Ex Abudante Cautela alleging lack of jurisdiction in view of the absence of an order to litigate, failure to state a cause of action and lack of personality to sue. Respondent bank in the other civil case (CC-11139) for damages moved to dismiss suit in view of the existence already of the Interpleader case. The trial court in the interpleader case issued an order dated July 13, 1984, denying the motion to dismiss of petitioner Mesina and ruling that respondent bank's complaint sufficiently pleaded a cause of action for itnerpleader. Petitioner filed his motion for reconsideration which was denied by the trial court on September 26, 1984. Upon motion for respondent Jose Go dated October 31, 1984, respondent judge issued an order on November 6, 1984, declaring petitioner in default since his period to answer has already expirecd and set the ex-parte presentation of respondent bank's evidence on November 7, 1984. Petitioner Mesina filed a petition for certioari with preliminary injunction with IAC to set aside 1) order of respondent court denying his omnibus Motion to Dismiss 2) order of 3) the order of default against him. On January 22, 1985, IAC rendered its decision dimissing the petition for certiorari. Petitioner Mesina filed his Motion for Reconsideration which was also denied by the same court in its resolution dated February 18, 1985. Meanwhile, on same date (February 18, 1985), the trial court in Civil Case #84-22515 (Interpleader) rendered a decisio, the dispositive portion reading as follows: WHEREFORE, in view of the foregoing, judgment is hereby rendered ordering plaintiff Associate Bank to replace Cashier's Check No. 011302 in favor of Jose Go or its cas equivalent with legal rate of itnerest from date of complaint, and with costs of suit against the latter.

SO ORDERED. On March 29, 1985, the trial court in Civil Case No. C-11139, for damages, issued an order, the pertinent portion of which states: The records of this case show that on August 20, 1984 proceedings in this case was (were) ordered suspended because the main issue in Civil Case No. 84-22515 and in this instant case are the same which is: who between Marcelo Mesina and Jose Go is entitled to payment of Associated Bank's Cashier's Check No. CC-011302? Said issue having been resolved already in Civil casde No. 84-22515, really this instant case has become moot and academic. WHEREFORE, in view of the foregoing, the motion sholud be as it is hereby granted and this case is ordered dismissed. In view of the foregoing ruling no more action should be taken on the "Motion For Reconsideration (of the order admitting the Intervention)" dated June 21, 1984 as well as the Motion For Reconsideration dated September 10, 1984. SO ORDERED. Petitioner now comes to Us, alleging that: 1. IAC erred in ruling that a cashier's check can be countermanded even in the hands of a holder in due course. 2. IAC erred in countenancing the filing and maintenance of an interpleader suit by a party who had earlier been sued on the same claim. 3. IAC erred in upholding the trial court's order declaring petitioner as in default when there was no proper order for him to plead in the interpleader complaint. 4. IAC went beyond the scope of its certiorari jurisdiction by making findings of facts in advance of trial. Petitioner now interposes the following prayer: 1. Reverse the decision of the IAC, dated January 22, 1985 and set aside the February 18, 1985 resolution denying the Motion for Reconsideration. 2. Annul the orders of respondent Judge of RTC Manila giving due course to the interpleader suit and declaring petitioner in default.

Petitioner's allegations hold no water. Theories and examples advanced by petitioner on causes and effects of a cashier's check such as 1) it cannot be countermanded in the hands of a holder in due course and 2) a cashier's check is a bill of exchange drawn by the bank against itself-are general principles which cannot be aptly applied to the case at bar, without considering other things. Petitioner failed to substantiate his claim that he is a holder in due course and for consideration or value as shown by the established facts of the case. Admittedly, petitioner became the holder of the cashier's check as endorsed by Alexander Lim who stole the check. He refused to say how and why it was passed to him. He had therefore notice of the defect of his title over the check from the start. The holder of a cashier's check who is not a holder in due course cannot enforce such check against the issuing bank which dishonors the same. If a payee of a cashier's check obtained it from the issuing bank by fraud, or if there is some other reason why the payee is not entitled to collect the check, the respondent bank would, of course, have the right to refuse payment of the check when presented by the payee, since respondent bank was aware of the facts surrounding the loss of the check in question. Moreover, there is no similarity in the cases cited by petitioner since respondent bank did not issue the cashier's check in payment of its obligation. Jose Go bought it from respondent bank for purposes of transferring his funds from respondent bank to another bank near his establishment realizing that carrying money in this form is safer than if it were in cash. The check was Jose Go's property when it was misplaced or stolen, hence he stopped its payment. At the outset, respondent bank knew it was Jose Go's check and no one else since Go had not paid or indorsed it to anyone. The bank was therefore liable to nobody on the check but Jose Go. The bank had no intention to issue it to petitioner but only to buyer Jose Go. When payment on it was therefore stopped, respondent bank was not the one who did it but Jose Go, the owner of the check. Respondent bank could not be drawer and drawee for clearly, Jose Go owns the money it represents and he is therefore the drawer and the drawee in the same manner as if he has a current account and he issued a check against it; and from the moment said cashier's check was lost and/or stolen no one outside of Jose Go can be termed a holder in due course because Jose Go had not indorsed it in due course. The check in question suffers from the infirmity of not having been properly negotiated and for value by respondent Jose Go who as already been said is the real owner of said instrument. In his second assignment of error, petitioner stubbornly insists that there is no showing of conflicting claims and interpleader is out of the question. There is enough evidence to establish the contrary. Considering the aforementioned facts and circumstances, respondent bank merely took the necessary precaution not to make a mistake as to whom to pay and therefore interpleader was its proper remedy. It has been shown that the interpleader suit was filed by respondent bank because petitioner and Jose Go were both laying their claims on the check, petitioner asking payment thereon and Jose Go as the purchaser or owner. The allegation of petitioner that respondent bank had effectively relieved itself of its primary liability under the check by simply filing a complaint for interpleader is belied by the willingness of respondent bank to issue a certificate of time deposit in the amount of P800,000 representing the cashier's check in question in the name of the Clerk of Court of Manila to be awarded to whoever wig be found by the court as validly entitled to it. Said validity will depend on the strength of the

parties' respective rights and titles thereto. Bank filed the interpleader suit not because petitioner sued it but because petitioner is laying claim to the same check that Go is claiming. On the very day that the bank instituted the case in interpleader, it was not aware of any suit for damages filed by petitioner against it as supported by the fact that the interpleader case was first entitled Associated Bank vs. Jose Go and John Doe, but later on changed to Marcelo A. Mesina for John Doe when his name became known to respondent bank. In his third assignment of error, petitioner assails the then respondent IAC in upholding the trial court's order declaring petitioner in default when there was no proper order for him to plead in the interpleader case. Again, such contention is untenable. The trial court issued an order, compelling petitioner and respondent Jose Go to file their Answers setting forth their respective claims. Subsequently, a Pre-Trial Conference was set with notice to parties to submit position papers. Petitioner argues in his memorandum that this order requiring petitioner to file his answer was issued without jurisdiction alleging that since he is presumably a holder in due course and for value, how can he be compelled to litigate against Jose Go who is not even a party to the check? Such argument is trite and ridiculous if we have to consider that neither his name or Jose Go's name appears on the check. Following such line of argument, petitioner is not a party to the check either and therefore has no valid claim to the Check. Furthermore, the Order of the trial court requiring the parties to file their answers is to all intents and purposes an order to interplead, substantially and essentially and therefore in compliance with the provisions of Rule 63 of the Rules of Court. What else is the purpose of a law suit but to litigate? The records of the case show that respondent bank had to resort to details in support of its action for Interpleader. Before it resorted to Interpleader, respondent bank took an precautionary and necessary measures to bring out the truth. On the other hand, petitioner concealed the circumstances known to him and now that private respondent bank brought these circumstances out in court (which eventually rendered its decision in the light of these facts), petitioner charges it with "gratuitous excursions into these nonissues." Respondent IAC cannot rule on whether respondent RTC committed an abuse of discretion or not, without being apprised of the facts and reasons why respondent Associated Bank instituted the Interpleader case. Both parties were given an opportunity to present their sides. Petitioner chose to withhold substantial facts. Respondents were not forbidden to present their side-this is the purpose of the Comment of respondent to the petition. IAC decided the question by considering both the facts submitted by petitioner and those given by respondents. IAC did not act therefore beyond the scope of the remedy sought in the petition. WHEREFORE, finding that the instant petition is merely dilatory, the same is hereby denied and the assailed orders of the respondent court are hereby AFFIRMED in toto. SO ORDERED. Feria (Chairman), Fernan, Alampay and Gutierrez, Jr., JJ., concur.

The Lawphil Project - Arellano Law Foundation Mesina vs IAC Marcelo A. Mesina vs. Intermediate Appellate Court G.R. No. 70145 November 13, 1986, 145 SCRA 497 --holder in due course FACTS: Jose Go purchased from Associated Bank a cashier's check for P800,000.00. Unfortunately, he left said check on the top of the desk of the bank manager when he left the bank. The bank manager entrusted the check for safekeeping to a bank official, a certain Albert Uy. While Uy went to the men's room, the check was stolen by his visitor in the person of Alexander Lim. Upon discovering that the check was lost, Jose Go accomplished a "STOP PAYMENT" order. Two days later, Associated Bank received the lost check for clearing from Prudential Bank. After dishonoring the same check twice, Associated Bank received summons and copy of a complaint for damages of Marcelo Mesina who was in possession of the lost check and is demanding payment. Petitioner claims that a cashier's check cannot be countermanded in the hands of a holder in due course. ISSUE: Whether or not petitioner can collect on the stolen check on the ground that he is a holder in due course. RULING: No. Petitioner failed to substantiate his claim that he is a holder in due course and for consideration or value as shown by the established facts of the case. Admittedly, petitioner became the holder of the cashier's check as endorsed by Alexander Lim who stole the check. He refused to say how and why it was passed to him. He had therefore notice of the defect of his title over the check from the start. The holder of a cashier's check who is not a holder in due course cannot enforce such check against the issuing bank which dishonors the same. **A person who became the holder of a cashier's check as endorsed by the person who stole it and who refused to say how and why it was passed to him is not a holder in due course.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Rule 16 To 36-1Dokument8 SeitenRule 16 To 36-1DenardConwiBesaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Doctor of Theology CurriculumDokument19 SeitenDoctor of Theology Curriculumsir_vic2013Noch keine Bewertungen

- Application Form For The Post of Junior Assistant/ Office Assistant (0111202101)Dokument3 SeitenApplication Form For The Post of Junior Assistant/ Office Assistant (0111202101)Randy OrtonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Law of Crimes End Term ProjectDokument22 SeitenLaw of Crimes End Term ProjectPooja PandeyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Preamble - DPP 7.1 - (CDS - 2 Viraat 2023)Dokument6 SeitenPreamble - DPP 7.1 - (CDS - 2 Viraat 2023)suyaldhruv979Noch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter III of Companies Act - Prospectus & Allotment of SecuritiesDokument11 SeitenChapter III of Companies Act - Prospectus & Allotment of SecuritiesJohn AllenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Plaintiff-Appellant Vs Vs Defendant-Appellee Claro M. Recto Damasceno Santos Ross, Selph, Carrascoso & JandaDokument10 SeitenPlaintiff-Appellant Vs Vs Defendant-Appellee Claro M. Recto Damasceno Santos Ross, Selph, Carrascoso & Jandamarites ongtengcoNoch keine Bewertungen

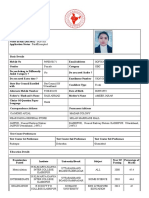

- APPLICATION FOR ALL INDIA BAR EXAMINATION AIBE-XVII - Preview ApplicationDokument2 SeitenAPPLICATION FOR ALL INDIA BAR EXAMINATION AIBE-XVII - Preview ApplicationMOHD AFZANoch keine Bewertungen

- Material A - Situs of TaxpayersDokument32 SeitenMaterial A - Situs of Taxpayerskookie bunnyNoch keine Bewertungen

- GR No 150274 PDFDokument7 SeitenGR No 150274 PDFAbs AcoonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Common Types of Contract Clauses A-ZDokument4 SeitenCommon Types of Contract Clauses A-ZMuhammad ArslanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2003 Sarmiento v. Spouses Sun CabridoDokument7 Seiten2003 Sarmiento v. Spouses Sun CabridoChristine Joy PamaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Midterms Notes - IpclDokument9 SeitenMidterms Notes - IpclBlaise VENoch keine Bewertungen

- Cir v. Domingo Jewellers Inc DigestDokument2 SeitenCir v. Domingo Jewellers Inc DigestjohanyarraNoch keine Bewertungen

- WHEREFORE, The Petition For Review On Certiorari Under Rule 45 of The Rules ofDokument14 SeitenWHEREFORE, The Petition For Review On Certiorari Under Rule 45 of The Rules ofCess LamsinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Robin v. Hardaway - Acts of Legislature Are VoidDokument21 SeitenRobin v. Hardaway - Acts of Legislature Are VoidgoldilucksNoch keine Bewertungen

- Privitization Office Management Vs CaDokument2 SeitenPrivitization Office Management Vs CaIñigo Mathay RojasNoch keine Bewertungen

- (1.) Rommel Was Issued A Certificate of Title Over ADokument18 Seiten(1.) Rommel Was Issued A Certificate of Title Over AMarco Mendenilla100% (2)

- Uy Vs BirDokument3 SeitenUy Vs Birjeanette4hijada100% (1)

- The Mirror DoctrineDokument12 SeitenThe Mirror DoctrineLeonardo De Caprio100% (1)

- Abbas V AbbasDokument2 SeitenAbbas V AbbasLotsee Elauria0% (1)

- Pafr Reviewer 1Dokument8 SeitenPafr Reviewer 1DEAN JASPERNoch keine Bewertungen

- Greg Lauer Named To Multi-Million Dollar Advocates Forum Press Release Aug. 2018Dokument2 SeitenGreg Lauer Named To Multi-Million Dollar Advocates Forum Press Release Aug. 2018CHRISTINA CURRIENoch keine Bewertungen

- DEED OF ABSOLUTE SALE - (Sample)Dokument3 SeitenDEED OF ABSOLUTE SALE - (Sample)Antonio RodriguezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Characteristics of A Contract of Partnership: I. Effect If The Above Requirements Are Not Complied WithDokument10 SeitenCharacteristics of A Contract of Partnership: I. Effect If The Above Requirements Are Not Complied WithJay jacinto100% (2)

- Answer KeyDokument4 SeitenAnswer KeySherwin Anoba CabutijaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2-A-1-4 - (2015) 1 SLR 26 - Lim Meng Suang V AGDokument70 Seiten2-A-1-4 - (2015) 1 SLR 26 - Lim Meng Suang V AGGiam Zhen KaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Types of PrisonDokument4 SeitenTypes of PrisonJayson BauyonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sec. Cert. Secdea BabakDokument2 SeitenSec. Cert. Secdea BabakDagul JauganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Practicum Report Legal OpinionDokument19 SeitenPracticum Report Legal OpinionCarmelie CumigadNoch keine Bewertungen