Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Executive Department Cases

Hochgeladen von

Armil Busico PuspusOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Executive Department Cases

Hochgeladen von

Armil Busico PuspusCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

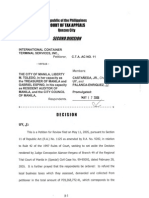

Joseph Estrada vs.

Aniano Disierto FACTS: After the sharp descent from power of Chavit Singson, he went on air and accused the petitioner of receiving millions of pesos from jueteng lords. Calls for resignation filled the air and former allies and members of the Presidents administration started resigning one by one. In a session on November 13, House Speaker Villar transmitted the Articles of Impeachment signed by 115 representatives or more than 1/3 of all the members of the House to the Senate. The impeachment trial formally opened which is the start of the dramatic fall from power of the President, which is most evident in the EDSA Dos rally. On January 20, the President submitted two letters one signifying his leave from the Palace and the other signifying his inability to exercise his powers pursuant to Section 11, Article VII of the Constitution. Thereafter, Arroyo took oath as President of the Philippines. ISSUES: Whether the petitioner resigned as President; and Whether the impeachment proceedings bar the petitioner from resigning RULING: For a resignation to be legally valid, there must be an intent to resign and the intent must be coupled by acts of relinquishment which may be oral or written, express or implied, for as long as the resignation is clear. In the press release containing his final statement, he acknowledged the oath-taking of Arroyo as President; he emphasized he was leaving the Palace without the mention of any inability and intent of reassumption; he expressed his gratitude to the people; he assured will not shirk from any future challenge that may come ahead in the same service of the country. This is of high grade evidence of his intent to resign. Petitioners contention that the impeachment proceeding is an administrative investigation that, under section 12 of RA 3019, bars him from resigning is not affirmed by the Court. The exact nature of an impeachment proceeding is debatable. But even assuming arguendo that it is an administrative proceeding, it cannot be considered pending at the time petitioner resigned because the process already broke down when a majority of the senator-judges voted against the opening of the second envelope, the public and private prosecutors walked out, the public prosecutors filed their Manifestation of Withdrawal of Appearance, and the proceedings were postponed indefinitely. There was, in effect, no impeachment case pending against the petitioner when he resigned. Civil Liberties Union VS. Executive Secretary FACTS: Petitioners: Ignacio P. Lacsina, Luis R. Mauricio, Antonio R. Quintos and Juan T. David for petitioners in 83896 and Juan T. David for petitioners in 83815. Both petitions were

consolidated and are being resolved jointly as both seek a declaration of the unconstitutionality of Executive Order No. 284 issued by President Corazon C. Aquino on July 25, 1987. Executive Order No. 284, according to the petitioners allows members of the Cabinet, their undersecretaries and assistant secretaries to hold other than government offices or positions in addition to their primary positions. The pertinent provisions of EO 284 is as follows: Section 1: A cabinet member, undersecretary or assistant secretary or other appointive officials of the Executive Department may in addition to his primary position, hold not more than two positions in the government and government corporations and receive the corresponding compensation therefor. Section 2: If they hold more positions more than what is required in section 1, they must relinquish the excess position in favor of the subordinate official who is next in rank, but in no case shall any official hold more than two positions other than his primary position. Section 3: AT least 1/3 of the members of the boards of such corporation should either be a secretary, or undersecretary, or assistant secretary. The petitioners are challenging EO 284s constitutionality because it adds exceptions to Section 13 of Article VII other than those provided in the constitution. According to the petitioners, the only exceptions against holding any other office or employment in government are those provided in the Constitution namely: 1. The Vice President may be appointed as a Member of the Cabinet under Section 3 par.2 of Article VII. 2. The secretary of justice is an ex-officio member of the Judicial and Bar Council by virtue of Sec. 8 of article VIII. Issue: Whether or not Executive Order No. 284 is constitutional. Decision: No. It is unconstitutional. Petition granted. Executive Order No. 284 was declared null and void. Ratio: In the light of the construction given to Section 13 of Article VII, Executive Order No. 284 is unconstitutional. By restricting the number of positions that Cabinet members, undersecretaries or assistant secretaries may hold in addition their primary position to not more that two positions in the government and government corporations, EO 284 actually allows them to hold multiple offices or employment in direct contravention of the express mandate of Sec. 13 of Article VII of the 1987 Constitution prohibiting them from doing so, unless otherwise provided in the 1987 Constitution itself. The phrase unless otherwise provided in this constitution must be given a literal interpretation to refer only to those particular instances cited in the constitution itself: Sec. 3 Art VII and Sec. 8 Art. VIII. Marcos vs Manglapus

Biraogo vs Philippine Truth Commission of 2010 Facts: The genesis of the foregoing cases can be traced to the events prior to the historic May2010 elections, when then Senator Benigno Simeon Aquino III declared his staunchcondemnation of graft and corruption with his slogan, "Kung walang corrupt, walangmahirap." The Filipino people, convinced of his sincerity and of his ability to carry out thisnoble objective, catapulted the good senator to the presidency.The first case is G.R. No. 192935, a special civil action for prohibition instituted bypetitioner Louis Biraogo (Biraogo) in his capacity as a citizen and taxpayer. Biraogoassails Executive Order No. 1 for being violative of the legislative power of Congressunder Section 1, Article VI of the Constitution as it usurps the constitutional authority of the legislature to create a public office and to appropriate funds therefor.The second case, G.R. No. 193036, is a special civil action for certiorari and prohibitionfiled by petitioners Edcel C. Lagman, Rodolfo B. Albano Jr., Simeon A. Datumanong,and Orlando B. Fua, Sr. (petitionerslegislators) as incumbent members of the House of Representatives.Thus, at the dawn of his administration, the President on July 30, 2010, signedExecutive Order No. 1 establishing the Philippine Truth Commission of 2010 (TruthCommission). Issue: Whether or not Executive Order No. 1 violates the principle of separation of powers byusurping the powers of Congress to create and to appropriate funds for public offices,agencies and commissions. Held: Power of the President to Create the Truth Commission The Chief Executives power to create the Ad hoc Investigating Committee cannot bedoubted. Having been constitutionally granted full control of the Executive Department,to which respondents belong, the President has the obligation to ensure that allexecutive officials and employees faithfully comply with the law. With AO 298 asmandate, the legality of the investigation is sustained. Such validity is not affected by thefact that the investigating team and the PCAGC had the same composition, or that theformer used the offices and facilities of the latter in conducting the inquiry. Villena vs Secretary of the Interior Political Law Control Power Supervision Suspension of a Local Government Official FACTS: Villena was the then mayor of Makati. After investigation, the Secretary of Interior recommended the suspension of Villena with the Office of the president who approved the same. The Secretary then suspended Villena. Villena

averred claiming that the Secretary has no jurisdiction over the matter. The power or jurisdiction is lodged in the local government [the governor] pursuant to sec 2188 of the Administrative Code. Further, even if the respondent Secretary of the Interior has power of supervision over local governments, that power, according to the constitution, must be exercised in accordance with the provisions of law and the provisions of law governing trials of charges against elective municipal officials are those contained in sec 2188 of the Administrative Code as amended. In other words, the Secretary of the Interior must exercise his supervision over local governments, if he has that power under existing law, in accordance with sec 2188 of the Administrative Code, as amended, as the latter provisions govern the procedure to be followed in suspending and punishing elective local officials while sec 79 (C) of the Administrative Code is the genera law which must yield to the special law. ISSUE: Whether or not the Secretary of Interior can suspend an LGU official under investigation. HELD: There is no clear and express grant of power to the secretary to suspend a mayor of a municipality who is under investigation. On the contrary, the power appears lodged in the provincial governor by sec 2188 of the Administrative Code which provides that The provincial governor shall receive and investigate complaints made under oath against municipal officers for neglect of duty, oppression, corruption or other form of maladministration of office, and conviction by final judgment of any crime involving moral turpitude. The fact, however, that the power of suspension is expressly granted by sec 2188 of the Administrative Code to the provincial governor does not mean that the grant is necessarily exclusive and precludes the Secretary of the Interior from exercising a similar power. For instance, counsel for the petitioner admitted in the oral argument that the President of the Philippines may himself suspend the petitioner from office in virtue of his greater power of removal (sec. 2191, as amended, Administrative Code) to be exercised conformably to law. Indeed, if the President could, in the manner prescribed by law, remove a municipal official; it would be a legal incongruity if he were to be devoid of the lesser power of suspension. And the incongruity would be more patent if, possessed of the power both to suspend and to remove a provincial official (sec. 2078, Administrative Code), the President were to be without the power to suspend a municipal official. The power to suspend a municipal official is not exclusive. Preventive suspension may be issued to give way for an impartial investigation. Lacson-Magallanes Co. vs Pao & Executive Secretary Pajo

Political Law Delegation of Control Power to the Executive Secretary FACTS: Magallanes was permitted to use and occupy a land used for pasture in Davao. The said land was a forest zone which was later declared as an agricultural zone. Magallanes then ceded his rights to LMC of which he is a co-owner. Pao was a farmer who asserted his claim over the same piece of land. The Director of Lands denied Paos request. The Secretary of Agriculture likewise denied his petition hence it was elevated to the Office of the President. Exec Sec Pajo ruled in favor of Pao. LMC averred that the earlier decision of the Secretary is already conclusive hence beyond appeal. He also averred that the decision of the Executive Secretary is an undue delegation of power. The Constitution, LMC asserts, does not contain any provision whereby the presidential power of control may be delegated to the Executive Secretary. It is argued that it is the constitutional duty of the President to act personally upon the matter. ISSUE: Whether or not the power of control may be delegated to the Exec Sec and may it be further delegated by the Exec Sec.

Secretary of Agriculture and Natural Resources, including the Director of Lands, may issue. Dadole vs COA Aytona vs Castillo Political Law Appointing Power Midnight Appointments FACTS: Aytona one was of those appointed by outgoing president Garcia during the last minute of his term. Aytona was appointed as the ad interim governor of the Central Bank. When Macapagal took his office as the next president he issued Order No. 2 which recalled Aytonas position and at the same time he appointed Castillo as the new governor of the Central Bank. Aytona then filed a quo warranto proceeding claiming that he is qualified to remain as the Central Bank governor and that he was validly appointed by the ex-president. Macapagal averred that the ex-presidents appointments were scandalous, irregular, hurriedly done, contrary to law and the spirit of which, and it was an attempt to subvert the incoming presidency or administration.

As a result, the JBC opened the position of Chief Justice for application or recommendation, and published for that purpose its announcement in the Philippine Daily Inquirer and the Philippine Star. In its meeting of February 8, 2010, the JBC resolved to proceed to the next step of announcing the names of the following candidates to invite to the public to file their sworn complaint, written report, or opposition, if any, not later than February 22, 2010. Although it has already begun the process for the filling of the position of Chief Justice Puno in accordance with its rules, the JBC is not yet decided on when to submit to the President its list of nominees for the position due to the controversy in this case being unresolved. The compiled cases which led to this case and the petitions of intervenors called for either the prohibition of the JBC to pass the shortlist, mandamus for the JBC to pass the shortlist, or that the act of appointing the next Chief Justice by GMA is a midnight appointment. A precedent frequently cited by the parties is the In Re Appointments Dated March 30, 1998 of Hon. Mateo A. Valenzuela and Hon. Placido B. Vallarta as Judges of the RTC of Branch 62, Bago City and of Branch 24, Cabanatuan City, respectively, shortly referred to here as the Valenzuela case, by which the Court held that Section 15, Article VII prohibited the exercise by the President of the power to appoint to judicial positions during the period therein fixed.

Had the framers intended to extend the prohibition contained in Section 15, Article VII to the appointment of Members of the Supreme Court, they could have explicitly done so. They could not have ignored the meticulous ordering of the provisions. They would have easily and surely written the prohibition made explicit in Section 15, Article VII as being equally applicable to the appointment of Members of the Supreme Court in Article VIII itself, most likely in Section 4 (1), Article VIII. That such specification was not done only reveals that the prohibition against the President or Acting President making appointments within two months before the next presidential elections and up to the end of the Presidents or Acting Presidents term does not refer to the Members of the Supreme Court. We cannot permit the meaning of the Constitution to be stretched to any unintended point in order to suit the purposes of any quarter MATIBAG VS. BENIPAYO comelec temporary appointments

FACTS: President GMA appointed, ad interim, Benipayo as COMELEC Chairman,3 and Borra4 and ISSUE: Whether or not Aytona should remain in his post. HELD: The Presidents duty to execute the law is of Tuason5 as COMELEC Commissioners, each for a term constitutional origin. So, too, is his control of all of seven years and all expiring on February 2, 2008. They HELD: Had the appointment of Aytona been done in good executive departments. Thus it is, that department all took their oath of office and assumed the positions. faith then he would have the right to continue office. Here, heads are men of his confidence. His is the power to The Office of the President submitted to the Commission even though Aytona is qualified to remain in his post as appoint them; his, too, is the privilege to dismiss them at on Appointments the ad interim appointments of he is competent enough, his appointment can pleasure. Naturally, he controls and directs their acts. Benipayo, Borra and Tuason for confirmation.6 However, nevertheless be revoked by the president. Garcias Implicit then is his authority to go over, confirm, modify or appointments are hurried maneuvers to subvert the the Commission on Appointments did not act on said reverse the action taken by his department secretaries. In upcoming administration and is set to obstruct the policies Issues: appointments. this context, it may not be said that the President cannot Whether or not Section 15, Article VII of the Phil Consti. President Arroyo renewed the ad interim of the next president. As a general rule, once a person is rule on the correctness of a decision of a department does not lead to an interpretation that exempts judicial appointments of Benipayo, Borra and Tuason to the same qualified his appointment should not be revoked but in secretary. Parenthetically, it may be stated that the right appointments from the express ban on midnight positions and for the same term of seven years. They here it may be since his appointment was grounded on to appeal to the President reposes upon the Presidents appointments took their oaths of office for a second time. The Office of bad faith, immorality and impropriety. In public service, it power of control over the executive departments. And the President transmitted their appointments to the is not only legality that is considered but also justice, control simply means the power of an officer to alter or RULING: Commission on Appointments for confirmation. fairness and righteousness. modify or nullify or set aside what a subordinate officer The court denies the motions for reconsideration for lack Congress adjourned before the Commission on had done in the performance of his duties and to of merit, for all the matters being thereby raised and Appointments could act on their appointments. De Castro v. JBC substitute the judgment of the former for that of the latter. Facts: argued, not being new, have all been resolved by the In his capacity as Comelec Chair, Benipayo decision of March17, 2010. Nonetheless, the Court opts issued a Memorandum, reassigning Matibag to the from This case is based on multiple cases field with dealt with It is correct to say that constitutional powers there are to dwell on some matters only for the purpose of the Education Department to the Law Department the controversy that has arisen from the forthcoming which the President must exercise in person. Not as Matibag sought reconsideration, arguing that compulsory requirement of Chief Justice Puno on May 17, clarification and emphasis. correct, however, is it to say that the Chief Executive may 2010 or seven days after the presidential election. On transfer and detail of employees are prohibited during the not delegate to his Executive Secretary acts which the Most of the movants contend that the principle of stare election period, both by the Election Code and a Civil December 22, 2009, Congressman Matias V. Defensor, Constitution does not command that he perform in decisis is controlling, and accordingly insist that the Court Service Memorandum an ex officio member of the JBC, addressed a letter to the person. Reason is not wanting for this view. The has erred in disobeying or abandoning Valenzuela ruling, Matibag filed an administrative and criminal JBC, requesting that the process for nominations to the President is not expected to perform in person all the case against Benipayo. office of the Chief Justice be commenced immediately. multifarious executive and administrative functions. The It has been insinuated as part of the polemics attendant to Matibag also questioned the appointment and office of the Executive Secretary is an auxiliary unit which In its January 18, 2010 meeting en banc, the JBC passed the controversy we are resolving that because all the the right to remain in office of Benipayo, Borra and assists the President. The rule which has thus gained Members of the present Court were appointed by the Tuason, as Chairman and Commissioners of the a resolution which stated that they have unanimously recognition is that under our constitutional setup the incumbent President, a majority of them are now granting COMELEC, respectively. Petitioner claims that the ad agreed to start the process of filling up the position of Executive Secretary who acts for and in behalf and by to her the authority to appoint the successor of the retiring interim appointments of Benipayo, Borra and Tuason Chief Justice to be vacated on May 17, 2010 upon the authority of the President has an undisputed jurisdiction to retirement of the incumbent Chief Justice. Chief Justice. violate the constitutional provisions on the independence affirm, modify, or even reverse any order that the of the COMELEC, as well as on the prohibitions on

temporary appointments and reappointments of its Chairman and members. Petitioner posits the view that an ad interim appointment can be withdrawn or revoked by the President at her pleasure, and can even be disapproved or simply by-passed by the Commission on Appointments. For this reason, petitioner claims that an ad interim appointment is temporary in character and consequently prohibited by the last sentence of Section 1 (2), Article IX-C of the Constitution. The rationale behind petitioners theory is that only an appointee who is confirmed by the Commission on Appointments can guarantee the independence of the COMELEC. A confirmed appointee is beyond the influence of the President or members of the Commission on Appointments since his appointment can no longer be recalled or disapproved. Prior to his confirmation, the appointee is at the mercy of both the appointing and confirming powers since his appointment can be terminated at any time for any cause. Petitioner also agues that assuming the first ad interim appointments and the first assumption of office by Benipayo, Borra and Tuason are constitutional, the renewal of the their ad interim appointments and their subsequent assumption of office to the same positions violate the prohibition on reappointment under Section 1 (2), Article IX-C of the Constitution. Petitioner theorizes that once an ad interim appointee is by-passed by the Commission on Appointments, his ad interim appointment can no longer be renewed because this will violate Section 1 (2), Article IX-C of the Constitution which prohibits reappointments. Petitioner asserts that this is particularly true to permanent appointees who have assumed office, which is the situation of Benipayo, Borra and Tuason if their ad interim appointments are deemed permanent in character. ISSUES: 1. Whether or not the assumption of office by Benipayo, Borra and Tuason on the basis of the ad interim appointments issued by the President amounts to a temporary appointment prohibited by Section 1 (2), Article IX-C of the Constitution; 2. Assuming that the first ad interim appointments and the first assumption of office by Benipayo, Borra and Tuason are legal, whether or not the renewal of their ad interim appointments and subsequent assumption of office to the same positions violate the prohibition on reappointment under Section 1 (2), Article IX-C of the Constitution; SC: 1. MATIBAG IS WRONG. An ad interim appointment is a permanent appointment because it takes effect immediately and can no longer be withdrawn by the President once the appointee has qualified into office. The fact that it is subject to

confirmation by the Commission on Appointments does not alter its permanent character. The Constitution itself makes an ad interim appointment permanent in character by making it effective until disapproved by the Commission on Appointments or until the next adjournment of Congress. Thus, the ad interim appointment remains effective until such disapproval or next adjournment, signifying that it can no longer be withdrawn or revoked by the President. The fear that the President can withdraw or revoke at any time and for any reason an ad interim appointment is utterly without basis. 2. An ad interim appointment that is by-passed because of lack of time or failure of the Commission on Appointments to organize is another matter. A by-passed appointment is one that has not been finally acted upon on the merits by the Commission on Appointments at the close of the session of Congress. There is no final decision by the Commission on Appointments to give or withhold its consent to the appointment as required by the Constitution. Absent such decision, the President is free to renew the ad interim appointment of a by-passed appointee. Thus, a by-passed appointment can be considered again if the President renews the appointment. In short, an ad interim appointment ceases to be effective upon disapproval by the Commission, because the incumbent can not continue holding office over the positive objection of the Commission. It ceases, also, upon "the next adjournment of the Congress", simply because the President may then issue new appointments - not because of implied disapproval of the Commission deduced from its inaction during the session of Congress, for, under the Constitution, the Commission may affect adversely the interim appointments only by action, never by omission. If the adjournment of Congress were an implied disapproval of ad interim appointments made prior thereto, then the President could no longer appoint those so by-passed by the Commission. But, the fact is that the President may reappoint them, thus clearly indicating that the reason for said termination of the ad interim appointments is not the disapproval thereof allegedly inferred from said omission of the Commission, but the circumstance that upon said adjournment of the Congress, the President is free to make ad interim appointments or reappointments." The prohibition on reappointment in Section 1 (2), Article IX-C of the Constitution applies neither to disapproved nor by-passed ad interim appointments. A disapproved ad interim appointment cannot be revived by another ad interim appointment because the disapproval is final under Section 16, Article VII of the Constitution, and not because a reappointment is prohibited under Section 1 (2), Article IX-C of the Constitution. A bypassed ad interim appointment can be revived by a new ad interim appointment because there is no final disapproval under Section 16, Article VII of the

Constitution, and such new appointment will not result in the appointee serving beyond the fixed term of seven years. Section 1 (2), Article IX-C of the Constitution provides that "[t]he Chairman and the Commissioners shall be appointed x x x for a term of seven years without reappointment." (Emphasis supplied) There are four situations where this provision will apply. The first situation is where an ad interim appointee to the COMELEC, after confirmation by the Commission on Appointments, serves his full seven-year term. Such person cannot be reappointed to the COMELEC, whether as a member or as a chairman, because he will then be actually serving more than seven years. The second situation is where the appointee, after confirmation, serves a part of his term and then resigns before his seven-year term of office ends. Such person cannot be reappointed, whether as a member or as a chair, to a vacancy arising from retirement because a reappointment will result in the appointee also serving more than seven years. The third situation is where the appointee is confirmed to serve the unexpired term of someone who died or resigned, and the appointee completes the unexpired term. Such person cannot be reappointed, whether as a member or chair, to a vacancy arising from retirement because a reappointment will result in the appointee also serving more than seven years. The fourth situation is where the appointee has previously served a term of less than seven years, and a vacancy arises from death or resignation. Even if it will not result in his serving more than seven years, a reappointment of such person to serve an unexpired term is also prohibited because his situation will be similar to those appointed under the second sentence of Section 1 (2), Article IX-C of the Constitution. This provision refers to the first appointees under the Constitution whose terms of office are less than seven years, but are barred from ever being reappointed under any situation. Not one of these four situations applies to the case of Benipayo, Borra or Tuason.

lapses is neither a fixed term nor an unexpired term. To hold otherwise would mean that the President by his unilateral action could start and complete the running of a term of office in the COMELEC without the consent of the Commission on Appointments. This interpretation renders inutile the confirming power of the Commission on Appointments. The phrase "without reappointment" applies only to one who has been appointed by the President and confirmed by the Commission on Appointments, whether or not such person completes his term of office. There must be a confirmation by the Commission on Appointments of the previous appointment before the prohibition on reappointment can apply. To hold otherwise will lead to absurdities and negate the Presidents power to make ad interim appointments. In the great majority of cases, the Commission on Appointments usually fails to act, for lack of time, on the ad interim appointments first issued to appointees. If such ad interim appointments can no longer be renewed, the President will certainly hesitate to make ad interim appointments because most of her appointees will effectively be disapproved by mere inaction of the Commission on Appointments. This will nullify the constitutional power of the President to make ad interim appointments, a power intended to avoid disruptions in vital government services. This Court cannot subscribe to a proposition that will wreak havoc on vital government services. The prohibition on reappointment is common to the three constitutional commissions. The framers of the present Constitution prohibited reappointments for two reasons. The first is to prevent a second appointment for those who have been previously appointed and confirmed even if they served for less than seven years. The second is to insure that the members of the three constitutional commissions do not serve beyond the fixed term of seven years.

As to the transfer of Matibag COMELEC Resolution No. 3300 does not require that every transfer or reassignment of COMELEC personnel should carry the concurrence of the COMELEC To foreclose this interpretation, the phrase as a collegial body. Interpreting Resolution No. 3300 to "without reappointment" appears twice in Section 1 (2), require such concurrence will render the resolution Article IX-C of the present Constitution. The first phrase meaningless since the COMELEC en banc will have to prohibits reappointment of any person previously approve every personnel transfer or reassignment, appointed for a term of seven years. The second phrase making the resolution utterly useless. Resolution No. prohibits reappointment of any person previously 3300 should be interpreted for what it is, an approval to appointed for a term of five or three years pursuant to the effect transfers and reassignments of personnel, without first set of appointees under the Constitution. In either need of securing a second approval from the COMELEC case, it does not matter if the person previously appointed en banc to actually implement such transfer or completes his term of office for the intention is to prohibit reassignment. any reappointment of any kind. The COMELEC Chairman is the official However, an ad interim appointment that has expressly authorized by law to transfer or reassign lapsed by inaction of the Commission on Appointments COMELEC personnel. The person holding that office, in a does not constitute a term of office. The period from the de jure capacity, is Benipayo. The COMELEC en banc, in time the ad interim appointment is made to the time it COMELEC Resolution No. 3300, approved the transfer or

reassignment of COMELEC personnel during the election period. Thus, Benipayos order reassigning petitioner from the EID to the Law Department does not violate Section 261 (h) of the Omnibus Election Code. De Rama vs. CA Facts: Upon his assumption to the position of Mayor of Pagbilao, Quezon, petitoner Conrado De Rama wrote a letter to the CSC seeking the recall of the appointments of 14 municipal employees. Petitioner justified his recall request on the allegation that the appointments of said employees were midnight appointments of the former mayor, done in violation of Art. VII, Sec. 15 of the Constitution. The CSC denied petitioners request for the recall of the appointments of the 14 employees for lack of merit. The CSC dismissed petitioners allegation that these were midnight appointments, pointing out that the constitutional provision relied upon by petitioner prohibits only those appointments made by an outgoing President and cannot be made to apply to local elective officials. The CSC opined that the appointing authority can validly issue appointments until his term has expired, as long as the appointee meets the qualification standards for the position.

(2) Whether or not the calling of the armed forces to assist the PNP in joint visibility patrols violates the constitutional provisions on civilian supremacy over the military and the civilian character of the PNP Held: When the President calls the armed forces to prevent or suppress lawless violence, invasion or rebellion, he necessarily exercises a discretionary power solely vested in his wisdom. Under Sec. 18, Art. VII of the Constitution, Congress may revoke such proclamation of martial law or suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus and the Court may review the sufficiency of the factual basis thereof. However, there is no such equivalent provision dealing with the revocation or review of the Presidents action to call out the armed forces. The distinction places the calling out power in a different category from the power to declare martial law and power to suspend the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus, otherwise, the framers of the Constitution would have simply lumped together the 3 powers and provided for their revocation and review without any qualification. The reason for the difference in the treatment of the said powers highlights the intent to grant the President the widest leeway and broadest discretion in using the power to call out because it is considered as the lesser and more benign power compared to the power to suspend the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus and the power to impose martial law, both of which involve the curtailment and suppression of certain basic civil rights and individual freedoms, and thus necessitating safeguards by Congress and review by the Court.

enlisted as members of the PNP, there can be no appointment to civilian position to speak of. Hence, the deployment of the Marines in the joint visibility patrols does not destroy the civilian character of the PNP. Lacson vs. Perez In quelling or suppressing the rebellion, the authorities may only resort to warrantless arrests of persons suspected of rebellion. FACTS: On May 1, 2001, President Macapagal-Arroyo, faced by an angry and violent mob armed with explosives, firearms, bladed weapons, clubs, stones and other deadly weapons assaulting and attempting to break into Malacaang, issued Proclamation No. 38 declaring that there was a state of rebellion in the National Capital Region. She likewise issued General Order No. 1 directing the Armed Forces of the Philippines and the Philippine National Police to suppress the rebellion in the National Capital Region. Warrantless arrests of several alleged leaders and promoters of the rebellion were thereafter effected.

The power to promulgate decrees belongs to the Legislature FACTS: These 7 consolidated petitions question the validity of PP 1017 (declaring a state of national emergency) and General Order No. 5 issued by President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo. While the cases are pending, President Arroyo issued PP 1021, declaring that the state of national emergency has ceased to exist, thereby, in effect, lifting PP 1017. ISSUE: Whether or not PP 1017 and G.O. No. 5 arrogated upon the President the power to enact laws and decrees If so, whether or not PP 1017 and G.O. No. 5 are unconstitutional HELD: Take-Care Power

This refers to the power of the President to ensure that the laws be faithfully executed, based on Sec. 17, Art. VII: Aggrieved by the warrantless arrests, and the declaration The President shall have control of all the executive of a state of rebellion, which allegedly gave a semblance departments, bureaus and offices. He shall ensure that of legality to the arrests, the following four related the laws be faithfully executed. Issue: Whether or not the appointments made by the petitions were filed before the Court. Prior to resolution, outgoing Mayor are forbidden under Art. VII, Sec. 15 of the state of rebellion was lifted in Metro Manila. As the Executive in whom the executive power is vested, the Constitution the primary function of the President is to enforce the ISSUE: laws as well as to formulate policies to be embodied in Held: The CSC correctly ruled that the constitutional Whether or not the declaration of a state of rebellion is existing laws. He sees to it that all laws are enforced by prohibition on so-called midnight appointments, constitutional the officials and employees of his department. Before specifically those made within 2 months immediately prior assuming office, he is required to take an oath or to the next presidential elections, applies only to the In view of the constitutional intent to give the President full affirmation to the effect that as President of the President or Acting President. There is no law that RULING: Philippines, he will, among others, execute its laws. In prohibits local elective officials from making appointments discretionary power to determine the necessity of calling out the armed forces, it is incumbent upon the petitioner As to warrantless arrests the exercise of such function, the President, if needed, during the last days of his or her tenure. to show that the Presidents decision is totally bereft of may employ the powers attached to his office as the factual basis. The present petition fails to discharge such As to petitioners claim that the proclamation of a state of Commander-in-Chief of all the armed forces of the IBP vs. Zamora heavy burden, as there is no evidence to support the rebellion is being used by the authorities to justify country, including the Philippine National Police under the Facts: assertion that there exists no justification for calling out warrantless arrests, the Secretary of Justice denies that it Department of Interior and Local Government. Invoking his powers as Commander-in-Chief under Sec. the armed forces. has issued a particular order to arrest specific persons in 18, Art. VII of the Constitution, the President directed the connection with the rebellion. xxx The specific portion of PP 1017 questioned is the AFP Chief of Staff and PNP Chief to coordinate with each The Court disagrees to the contention that by the enabling clause: to enforce obedience to all the laws and other for the proper deployment and utilization of the deployment of the Marines, the civilian task of law With this declaration, petitioners apprehensions as to to all decrees, orders and regulations promulgated by me Marines to assist the PNP in preventing or suppressing enforcement is militarized in violation of Sec. 3, Art. II of warrantless arrests should be laid to rest. personally or upon my direction. criminal or lawless violence. The President declared that the Constitution. The deployment of the Marines does not the services of the Marines in the anti-crime campaign are constitute a breach of the civilian supremacy clause. The In quelling or suppressing the rebellion, the authorities Is it within the domain of President Arroyo to promulgate merely temporary in nature and for a reasonable period calling of the Marines constitutes permissible use of may only resort to warrantless arrests of persons decrees? only, until such time when the situation shall have military assets for civilian law enforcement. The local suspected of rebellion, as provided under Section 5, Rule The President is granted an Ordinance Power under improved. The IBP filed a petition seeking to declare the police forces are the ones in charge of the visibility patrols 113 of the Rules of Court, if the circumstances so Chap. 2, Book III of E.O. 292. President Arroyos deployment of the Philippine Marines null and void and at all times, the real authority belonging to the PNP warrant. The warrantless arrest feared by petitioners is, ordinance power is limited to those issuances mentioned unconstitutional. thus, not based on the declaration of a state of rebellion. in the foregoing provision. She cannot issue decrees Moreover, the deployment of the Marines to assist the similar to those issued by Former President Marcos under Issues: PNP does not unmake the civilian character of the police PP 1081. Presidential Decrees are laws which are of the David vs. Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo (1) Whether or not the Presidents factual determination of force. The real authority in the operations is lodged with same category and binding force as statutes because "Take Care" Power of the President the necessity of calling the armed forces is subject to the head of a civilian institution, the PNP, and not with the they were issued by the President in the exercise of his Powers of the Chief Executive judicial review military. Since none of the Marines was incorporated or

legislative power during the period of Martial Law under the 1973 Constitution. This Court rules that the assailed PP 1017 is unconstitutional insofar as it grants President Arroyo the authority to promulgate decrees. Legislative power is peculiarly within the province of the Legislature. Sec. 1, Art. VI categorically states that the legislative power shall be vested in the Congress of the Philippines which shall consist of a Senate and a House of Representatives. To be sure, neither Martial Law nor a state of rebellion nor a state of emergency can justify President Arroyos exercise of legislative power by issuing decrees. But can President Arroyo enforce obedience to all decrees and laws through the military? As this Court stated earlier, President Arroyo has no authority to enact decrees. It follows that these decrees are void and, therefore, cannot be enforced. With respect to laws, she cannot call the military to enforce or implement certain laws, such as customs laws, laws governing family and property relations, laws on obligations and contracts and the like. She can only order the military, under PP 1017, to enforce laws pertinent to its duty to suppress lawless violence.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Velasco vs. Villegas ordinance banning massage rooms in barbershops upheldDokument3 SeitenVelasco vs. Villegas ordinance banning massage rooms in barbershops upheldArmil Busico PuspusNoch keine Bewertungen

- CONSTITUTIONAL LAW FRAMEWORKDokument22 SeitenCONSTITUTIONAL LAW FRAMEWORKArmil Busico PuspusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Digest 1st Group - Consti 2Dokument2 SeitenCase Digest 1st Group - Consti 2Armil Busico PuspusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Microsoft Office 2007 - Kgfvy 7733b 8wck9 Ktg64 Bc7d8Dokument1 SeiteMicrosoft Office 2007 - Kgfvy 7733b 8wck9 Ktg64 Bc7d8MădălinaAstancăiNoch keine Bewertungen

- TransportationDokument557 SeitenTransportationArmil Busico Puspus100% (2)

- Mirasol vs. Court of AppealsDokument7 SeitenMirasol vs. Court of AppealsArmil Busico PuspusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Criminal Law Book OneDokument27 SeitenCriminal Law Book OneArmil Busico PuspusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Criminal Law Book OneDokument27 SeitenCriminal Law Book OneArmil Busico PuspusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Crim NotesDokument2 SeitenCrim NotesArmil Busico PuspusNoch keine Bewertungen

- HP V1810 Switch SeriesDokument8 SeitenHP V1810 Switch SeriesArmil Busico PuspusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Function of Judicial BranchDokument19 SeitenFunction of Judicial BranchCharisma Delos ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Juvenile Justice System (Amendment) Act, 2022 MuneebBookHouse 03014398492Dokument2 SeitenJuvenile Justice System (Amendment) Act, 2022 MuneebBookHouse 03014398492Muhammad Izhar AwanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 21225LLB037 - Amogh - Constitutional LawDokument19 Seiten21225LLB037 - Amogh - Constitutional LawAmogh SrivastavaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scra ConstiDokument202 SeitenScra ConstiLordz EspinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Administrative and Judicial Protest For Tax - Gantt Chart ProcessDokument13 SeitenAdministrative and Judicial Protest For Tax - Gantt Chart Processshie_fernandez9177Noch keine Bewertungen

- Taibo V R - 1996Dokument9 SeitenTaibo V R - 1996Moonmattie s100% (1)

- Rule 126 Search and Seizure CasesDokument19 SeitenRule 126 Search and Seizure CasespasmoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 08 de Leon v. ChuaDokument2 Seiten08 de Leon v. ChuaRioNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Powers of The Congress of The Philippines May Be Classified AsDokument9 SeitenThe Powers of The Congress of The Philippines May Be Classified AsJo Recile RamoranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Court upholds damages for rape, breach of promise to marryDokument6 SeitenCourt upholds damages for rape, breach of promise to marryRonnie Garcia Del RosarioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Amidu V KuffourDokument110 SeitenAmidu V KuffourMaame Ako100% (1)

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesDokument10 SeitenDepartment of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesJff ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal Professiona CasesDokument22 SeitenLegal Professiona CasesJohn Glenn LambayonNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2 People vs. TanDokument11 Seiten2 People vs. TanJantzenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Function of Law ReportDokument3 SeitenFunction of Law ReportzurainaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary Judgment Appellate Issues in TexasDokument49 SeitenSummary Judgment Appellate Issues in Texasmmeindl100% (1)

- Hierachy of Court ReportDokument9 SeitenHierachy of Court ReportNaqeeb Nexer100% (2)

- Motion For Postponement - Quintin Pagulayan Jr.Dokument3 SeitenMotion For Postponement - Quintin Pagulayan Jr.Salvado and Chua Law OfficesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rule 119 TrialDokument16 SeitenRule 119 TrialJoseph PamaongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Idolor VsCA 450 SCRA 396Dokument15 SeitenIdolor VsCA 450 SCRA 396Marc Gar-ciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Second Division: QuezonDokument23 SeitenSecond Division: QuezonAgnes Bianca MendozaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Third Division: People of The Philippines, Petitioner, vs. Maria Cristina P. Sergio and JULIUS L. LACANILAO, RespondentsDokument20 SeitenThird Division: People of The Philippines, Petitioner, vs. Maria Cristina P. Sergio and JULIUS L. LACANILAO, RespondentsoabeljeanmoniqueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Iglesia Ni Cristo vs. Heirs of Enrique G. SantosDokument62 SeitenIglesia Ni Cristo vs. Heirs of Enrique G. SantosGelli TabiraraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complaint To Judicial MagistrateDokument5 SeitenComplaint To Judicial MagistrateNidhi FaganiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- D 1 GN 20 003926 Dismissal OrderDokument3 SeitenD 1 GN 20 003926 Dismissal OrderRicca PrasadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Article VIII Judiciary Branch ConstiDokument29 SeitenArticle VIII Judiciary Branch ConstiDeanne Mitzi Somollo100% (1)

- Recall of Summons in Summons CasesDokument2 SeitenRecall of Summons in Summons CasesParvinder Singh AhluwaliaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comunicado de Prensa-Press Release 27 FebruaryDokument4 SeitenComunicado de Prensa-Press Release 27 FebruarypazycooperacionNoch keine Bewertungen

- (PS) Ervin v. Judicial Council of California Et Al - Document No. 33Dokument1 Seite(PS) Ervin v. Judicial Council of California Et Al - Document No. 33Justia.comNoch keine Bewertungen

- Air (1702 2109)Dokument554 SeitenAir (1702 2109)ujjwal-1989Noch keine Bewertungen