Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

At-Agamben Aff Style

Hochgeladen von

Harrison HaywardOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

At-Agamben Aff Style

Hochgeladen von

Harrison HaywardCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

AT-Agamben Kritik Aff Style (1/4)

1. Turn-Agambens alternative is built on a politics of universal friendship built upon the designation of an inhuman enemy, enabling endless violence Rasch, 03

[William, Henry, Prof of Germanic Studies at Indiana University. Human Rights as Geopolitics: Cultural Critique, 2003] Yes, this passage attests to the antiliberal prejudices of an unregenerate Eurocentric conservative with a pronounced affect for the counterrevolutionary and Catholic South of Europe. It seems to resonate with the apologetic mid-twentieth-century Spanish reception of Vitoria that wishes to justify the Spanish civilizing mission in the Americas. But the contrast between Christianity and humanism is not just prejudice; it is also instructive, because with it, Schmitt tries to grasp something both disturbing and elusive about the modern worldnamely, the apparent fact that the liberal and humanitarian attempt to construct a world of universal friendship produces, as if by internal necessity, ever new enemies. For Schmitt, the Christianity of Vitoria, of Salamanca, Spain, 1539, represents a concrete, spatially imaginable order, centered (still) in Rome and, ultimately, Jerusalem. This, with its divine revelations, its Greek philosophy, and its Roman language and institutions, is the polis. This is civilization, and outside its walls lie the barbarians. The humanism that Schmitt opposes is, in his words, a philosophy of absolute humanity. By virtue of its universality and

abstract normativity, it has no localizable polis, no clear distinction between what is inside and what is outside. Does humanity embrace all humans? Are there no gates to the city and thus no barbarians outside? If not, against whom or what does it wage its wars? We can understand Schmitt's concerns in the following way: Christianity distinguishes

between believers and nonbelievers. Since nonbelievers can become believers, they must be of the same category of being. To be human, then, is the horizon within which the distinction between believers and nonbelievers is made. That is, humanity per se is not part of the distinction, but is that which makes the distinction possible. However, once the term used to describe the horizon of a distinction

also becomes that distinction's positive pole, it needs its negative opposite. If humanity is both the horizon and the positive pole of the distinction that that horizon enables, then the negative pole can only be something that lies beyond that horizon, can only be something completely antithetical to horizon and positive pole alikecan only, in other words, be inhuman. As Schmitt says: Only with the concept of the

human in the sense of absolute humanity does there appear as the other side of this concept a specially new enemy, the inhuman. In the history of the nineteenth century, setting off the inhuman from the human is followed by an even deeper split, the one between the superhuman and the subhuman. In the same way that the human creates the inhuman, so in the history of humanity the superhuman brings about with a dialectical necessity the subhuman as its enemy twin.9 This "two-sided aspect of the ideal of humanity" (Schmitt 1988, Der Nomos der Erde, 72) is a theme Schmitt had already developed in his The Concept of the Political (1976) and his critiques of liberal pluralism (e.g., 1988, Positionen und Begriffe, 151-65). His complaint there is that liberal pluralism is in fact not in the least pluralist but reveals itself to be an overriding monism, the monism of humanity. Thus, despite the claims that pluralism allows for the individual's freedom from illegitimate constraint, Schmitt presses the point home that political opposition to liberalism is itself deemed illegitimate. Indeed, liberal pluralism, in Schmitt's eyes, reduces the political to the social and economic and thereby nullifies all truly political opposition by simply excommunicating its opponents from the High Church of Humanity. After all, only an unregenerate barbarian could fail to recognize the irrefutable benefits of the liberal order.

This has two implications: a. The neg links to the harms of the NC since in trying to nullify distinctions they create an inside/outside dichotomy of those who accept the ethics of the NC and those who dont. b. This also results in the continual formation of bare life meaning that even if they win they break down some concept of bare life or sovereignty they inherently create more, meaning they cant terminally solve and recreate the harms of the NC. 2. Turn-Agambens thought and conception of bare life/sovereignty is inherently anthropocentric. Even if they win that they a risk of harms the ethics and thought used to justify the kritik are inherently anthropocentric meaning the kritik will always link to the harms of the AC.

AT-Agamben Kritik Aff Style (2/4)

3. Biopower doesnt create bare life; instead it produces extra-life. Ojakangas 5

[Mika, Doctorate in Social Science, Impossible Dialogue on Biopower, Foucault Studies] Moreover, life as the object and the subject of biopower given that life is everywhere, it becomes everywhere is in no way bare, but is as the synthetic notion of life implies, the multiplicity of the forms of life, from the nutritive life to the intellectual life, from the biological levels of life to the political existence of man.43

Instead of bare life, the life of biopower is a plenitude of life, as Foucault

puts it.44 Agamben is certainly right in saying that the production of bare life is, and has been since Aristotle, a main strategy of the sovereign power to establish itself to the same degree that sovereignty has been the main fiction of juridicoinstitutional thinking from Jean Bodin to Carl Schmitt. The sovereign

power is, indeed, based on bare life because it is capable of confronting life merely when stripped off and isolated from all forms of life, when the entire existence of a man is reduced to a bare life and exposed to an unconditional threat of death. Life is undoubtedly sacred for the sovereign power in the sense that Agamben defines it. It can be taken away without a homicide being committed. In the case of biopower, however, this does not hold true. In order to function properly, biopower cannot reduce life to the level of bare life, because bare life is life that

can only be taken away or allowed to persist which also makes understandable the vast critique of sovereignty in the era of biopower. Biopower

needs a notion of life that corresponds to its aims. What then is the aim of biopower? Its aim is not to produce bare life but, as Foucault emphasizes, to multiply life,45 to produce extralife.46 Biopower needs, in

other words, a notion of life which enables it to accomplish this task. The modern synthetic notion of life endows it with such a notion. It enables biopower to invest life through and through, to optimize forces, aptitudes, and life in general without at the same time making them more difficult to govern. It could be argued, of course, that instead of bare life (zoe) the form of life (bios) functions as the foundation of biopower. However, there is no room either for a bios in the modern biopolitical order because every bios has always been, as Agamben emphasizes, the result of the exclusion of zoe from the political realm. The modern biopolitical order does not exclude anything not even in the form of inclusive exclusion. As a matter of fact, in the era of biopolitics, life is already a bios that is only its own zoe. It

has

already moved into the site that Agamben suggests as the remedy of the political pathologies of modernity, that is to say, into the site where politics is freed from every ban and a form of life is wholly exhausted in bare life.48 At the end of Homo Sacer, Agamben

gives this life the name formoflife, signifying always and above all possibilities of life, always and above all power, understood as potentiality (potenza).49 According to Agamben, there would be no power that could

it is precisely this life, life as untamed power and potentiality, that biopower invests and optimizes. If biopower multiplies and optimizes life, it does so, above all, by multiplying and optimizing potentialities of life, by fostering and generating formsof life.50

have any hold over mens existence if life were understood as a formoflife. However,

This puts the neg into a double bind: either a) bare life isnt created due to biopower meaning the structures they outline as creating harms in the NC arent the case of those harms or b) their is no impact to the NC since biopower wont result in the extermination or exclusion of parts of the population.

AT-Agamben Kritik Aff Style (3/4)

4. Turn-Laclau a. Agamben basis his theory on three distinct claims Laclau, 07

[Ernesto, Professor at the University of Essex, holding a chair in political theory, and was the director of the doctoral program in Ideology and Discourse analysis . Bare Life or Social Indeterminancy, in Sovereignty and Life, p. 12]

the three theses in which Agamben summarizes his argument towards the end of Homo Sacer: 1. The original political relation is the ban (the state of exception as zone of indistinction between outside and inside, exclusion and inclusion). 2. The fundamental activity of sovereign power is the production of bare life as threshold of articulation between nature and culture, between zoe and bios. 3. Today it is not the city but rather the camp is that the fundamental biopolitical paradigm of the West. (HS, 181)

Let us start by considering

b. These claims are based upon false premises means the kritik fails Laclau, 07

[Ernesto, Professor at the University of Essex, holding a chair in political theory, and was the director of the doctoral program in Ideology and Discourse analysis . Bare Life or Social Indeterminancy, in Sovereignty and Life, p. 21-22]

This series of wild statements would only hold if the following set of rather dubious premises were accepted: 1. That the crisis of the functional nexus between land, State, and the automatic rules for the inscription of life has freed an entity called biological-or bare-life 2. That the regulation of that freed entity has been assumed by a single and unified entity necessarily leads it to treat the freed entities as entirely malleable objects whose archetypical form would be the ban. Needless to say, none of these presuppositions can be accepted as they stand.

Agamben, who has presented a rather compelling analysis of the way in which an ontology of potentiality should be structured, closes his argument, however, with a naive teleologism, in which potentially appears as entirely subordinated to a pre-given actuality. This teleologism is, as matter of fact, the symmetrical pendant of the ethymologism we have referred to at the beginning of this essay. Their combined effect is to divert Agambens attention from the really relevant question, which is the system of structural possibilities that each new situations opens. The

most summary examination of that system would have revealed that: (1) the crisis of the automatic rules for the inscription of life has freed many more entities than bare life, and that the reduction of the latter to the former takes place only in some extreme circumstances that cannot in the least be considered as a hidden pattern of modernity; (2) that the process of social regulation to which the dissolution of the automatic rules of inscription opens the way involved a plurality of instances that were far from unified in a single unity called the State; (3) that the process of State building in modernity has involved a far more complex dialectic between homogeneity and heterogeneity than the one that Agambens campbased paradigm reflects. By unifying the whole process of modern political construction around the extreme and absurd paradigm of the

AT-Agamben Kritik Aff Style (4/4)

concentration camp, Agamben does more than a present a distorted history: he blocks any possible exploration of the emancipatory possibilities opened by our modern heritage.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- FAQ and Known BugsDokument4 SeitenFAQ and Known BugsHarrison HaywardNoch keine Bewertungen

- Seeker Outline KoryDokument5 SeitenSeeker Outline KoryHarrison HaywardNoch keine Bewertungen

- House Rules Monday NightDokument1 SeiteHouse Rules Monday NightHarrison HaywardNoch keine Bewertungen

- Session StuffDokument14 SeitenSession StuffHarrison HaywardNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lumbermill DeckDokument230 SeitenLumbermill DeckHarrison HaywardNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analytical Report HaywardDokument5 SeitenAnalytical Report HaywardHarrison HaywardNoch keine Bewertungen

- Portfolio and Final IterationDokument22 SeitenPortfolio and Final IterationHarrison HaywardNoch keine Bewertungen

- Test 1 Proof-HaywardDokument1 SeiteTest 1 Proof-HaywardHarrison HaywardNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dragon Magazine #379Dokument93 SeitenDragon Magazine #379Harrison Hayward100% (2)

- At EmpthyDokument12 SeitenAt EmpthyHarrison HaywardNoch keine Bewertungen

- 13 TermsDokument5 Seiten13 TermsHarrison HaywardNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2AC Healthcare Block2Dokument1 Seite2AC Healthcare Block2Harrison HaywardNoch keine Bewertungen

- Neutron Bomb Testing Risks Global Overheating and Planetary ExplosionDokument1 SeiteNeutron Bomb Testing Risks Global Overheating and Planetary ExplosionHarrison HaywardNoch keine Bewertungen

- At EcoFemDokument4 SeitenAt EcoFemHarrison HaywardNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alaska Ports AffDokument66 SeitenAlaska Ports AffNicholas ChanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Willy DaDokument3 SeitenWilly DaHarrison HaywardNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evidence CollectionDokument7 SeitenEvidence CollectionHarrison HaywardNoch keine Bewertungen

- Math Final 2Dokument7 SeitenMath Final 2Harrison HaywardNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- FOCGB4 Utest VG 5ADokument1 SeiteFOCGB4 Utest VG 5Asimple footballNoch keine Bewertungen

- MatriarchyDokument11 SeitenMatriarchyKristopher Trey100% (1)

- IJAKADI: A Stage Play About Spiritual WarfareDokument9 SeitenIJAKADI: A Stage Play About Spiritual Warfareobiji marvelous ChibuzoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Opportunity, Not Threat: Crypto AssetsDokument9 SeitenOpportunity, Not Threat: Crypto AssetsTrophy NcNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aladdin and the magical lampDokument4 SeitenAladdin and the magical lampMargie Roselle Opay0% (1)

- The Insanity DefenseDokument3 SeitenThe Insanity DefenseDr. Celeste Fabrie100% (2)

- MA CHAPTER 2 Zero Based BudgetingDokument2 SeitenMA CHAPTER 2 Zero Based BudgetingMohd Zubair KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vegan Banana Bread Pancakes With Chocolate Chunks Recipe + VideoDokument33 SeitenVegan Banana Bread Pancakes With Chocolate Chunks Recipe + VideoGiuliana FloresNoch keine Bewertungen

- 05 Gregor and The Code of ClawDokument621 Seiten05 Gregor and The Code of ClawFaye Alonzo100% (7)

- Nazi UFOs - Another View On The MatterDokument4 SeitenNazi UFOs - Another View On The Mattermoderatemammal100% (3)

- BCIC General Holiday List 2011Dokument4 SeitenBCIC General Holiday List 2011Srikanth DLNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is Love? - Osho: Sat Sangha SalonDokument7 SeitenWhat Is Love? - Osho: Sat Sangha SalonMichael VladislavNoch keine Bewertungen

- PHEI Yield Curve: Daily Fair Price & Yield Indonesia Government Securities November 2, 2020Dokument3 SeitenPHEI Yield Curve: Daily Fair Price & Yield Indonesia Government Securities November 2, 2020Nope Nope NopeNoch keine Bewertungen

- FCE Listening Test 1-5Dokument20 SeitenFCE Listening Test 1-5Nguyễn Tâm Như Ý100% (2)

- Icici Bank FileDokument7 SeitenIcici Bank Fileharman singhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bianchi Size Chart for Mountain BikesDokument1 SeiteBianchi Size Chart for Mountain BikesSyafiq IshakNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2015 Ssang Yong Rexton Y292 Service ManualDokument1.405 Seiten2015 Ssang Yong Rexton Y292 Service Manualbogdanxp2000Noch keine Bewertungen

- Faxphone l100 Faxl170 l150 I-Sensys Faxl170 l150 Canofax L250seriesDokument46 SeitenFaxphone l100 Faxl170 l150 I-Sensys Faxl170 l150 Canofax L250seriesIon JardelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arx Occasional Papers - Hospitaller Gunpowder MagazinesDokument76 SeitenArx Occasional Papers - Hospitaller Gunpowder MagazinesJohn Spiteri GingellNoch keine Bewertungen

- HERMAgreenGuide EN 01Dokument4 SeitenHERMAgreenGuide EN 01PaulNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Class 8) MicroorganismsDokument3 Seiten(Class 8) MicroorganismsSnigdha GoelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Classification of Boreal Forest Ecosystem Goods and Services in FinlandDokument197 SeitenClassification of Boreal Forest Ecosystem Goods and Services in FinlandSivamani SelvarajuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sergei Rachmaninoff Moment Musicaux Op No in E MinorDokument12 SeitenSergei Rachmaninoff Moment Musicaux Op No in E MinorMarkNoch keine Bewertungen

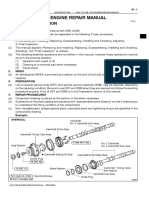

- How To Use This Engine Repair Manual: General InformationDokument3 SeitenHow To Use This Engine Repair Manual: General InformationHenry SilvaNoch keine Bewertungen

- FPR 10 1.lectDokument638 SeitenFPR 10 1.lectshishuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Meta Trader 4Dokument2 SeitenMeta Trader 4Alexis Chinchay AtaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Megha Rakheja Project ReportDokument40 SeitenMegha Rakheja Project ReportMehak SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Passive Voice Exercises EnglishDokument1 SeitePassive Voice Exercises EnglishPaulo AbrantesNoch keine Bewertungen

- HERBAL SHAMPOO PPT by SAILI RAJPUTDokument24 SeitenHERBAL SHAMPOO PPT by SAILI RAJPUTSaili Rajput100% (1)

- Midgard - Player's Guide To The Seven Cities PDFDokument32 SeitenMidgard - Player's Guide To The Seven Cities PDFColin Khoo100% (8)