Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

The Future of The Catholic Church in Igboland

Hochgeladen von

OSONDU JUDE THADDEUSOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The Future of The Catholic Church in Igboland

Hochgeladen von

OSONDU JUDE THADDEUSCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

THE FUTURE OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN IGBOLAND BY FR CORNELIUS OKEKE CRITIQUE The author seems to lay too much

h emphasis on the Igbo culture as if to say the Igbo culture were intrinsically antithetical to the Catholic priesthood. After all, the Igbo African Traditional religion had priests who were also enjoying the generosity and reverence of the Igbos like the Catholic priests do today, but the Igbo traditional priests were not known to be as acquisitive and flamboyant as the Igbo Catholic priests are today. Yes, we acknowledge the strong influence of culture on people, but not to the point of nearexaggeration as the author almost makes us believe. Also, while the author blames ineffective formation for the difference between the religious and the diocesan seminarians, he appears to neglect an important factor, i.e., the concrete circumstances surrounding their life and work, in fact, their different missions. The diocesan takes care of his own bills and daily expenses to a very large extent, while the religious is taken care of by his congregation, to a very large extent as well. So judging them both on the basis of acquisitiveness and condemning this as a defect in one may not be fair after all, because the other is practically meant to be less acquisitive because he is being totally taken care of. In the same vein, he talks of the two types of formation in vogue in Nigeria the institutional/conformity and the progressive models; the former witnessed more in the seminaries, the latter found more in congregations. A formation model is drawn based on the intended mission of those to be formed in it. He criticizes the diocesan formation as being too intellectualistic while the religious is more relaxed, so to say. Nevertheless, one may give him an instance with the Jesuits, who are of course religious, known to have education as their primary apostolate. Would we suppose that their formation would not be rather intellectualistic? Different congregations have different apostolates, ranging from orphanages, the sick, aged, youths, etc. Of course, one would not expect to find too much intellectualistic emphasis in their own formation. Now, the secular priest has a different apostolate, and therefore, has to be well-equipped to function optimally in the environment he finds himself. Christ himself forewarns: Behold, I send you out into the world as sheep amidst wolves. Be wise as serpents and gentle as doves (Mat. 10:16). Here, the author again overlooks the fundamental differences in the apostolates of diocesans and religious, which the formation model tries to prepare them for. He critiques them at face value rather than the underlying factors. In addition, the formation model he proposes has some issues unresolved. First, he does not state whether it is for diocesans or for religious or for both. If it is for both, it does not put into consideration the differences in their apostolates and orientations. Second, he is not clear on how to fit perfectly the cultural traits of the seminarians into their seminary formation and priestly life. Third, he insists on reducing the number of seminarians for his formation blueprint to be effective, instead of stipulating how it could be effectively applied in the current existential situation of our over-crowded seminaries. So, in fact, it

cannot work as long as there is vocation boom. Fourth, his insistence on reduction of numbers is difficult to reconcile with his appreciation of the vocation boom in Igboland. This apparent contradiction could be due to either lack of consistency or lack of clarity. If you reduce the number of those in the seminaries, I strongly believe most of the currentlyperceived defects of the current formation systems would be resolved. What is really needed right now is not as much as a new utopian formation system as ways of making the existing ones more effective in spite of the stiff challenges facing it like number and so on. On the issue of most of the shadows of the priests like their acquisitiveness, highhandedness in exercising authority, seeing themselves as above all else, etc, I dare say that the problem ought not be seen from an excessive cultural angle but also to a large extent, from the historical angle, particularly the effects of colonialism and the white missionaries. These whites then were seen as a special or superhuman class. They were accorded utmost respect, nay, fear, like gods. Generousity to them was an honour to the benefactor. Our people subsequently attached this deference for the whites to the priesthood as wel. This mentality made the indigenous priests who came after them and who also inherited the tradition of subservience to the priests, take it for granted as their right. Now, the tension is because the people now want to expunge that mentality of the priests superiority because the whites have left. It is not because the priests today have put up any new attitudes, but that the people are now seeing them as fellow blacks, fellow Igbos and so, fellow men or equals. An Igbo adage says: John ulo bu nwa John; John mba bu De John (i.e., the John at home is little John; the John that is a strange is Mr John). Christ suffered this fraternal disregard also, not because H e had any shadows, but simply because they knew His origin. Furthermore, as a formator himself, he does not say whether he has put into practice the formation method he prescribed, or how successful he was with it, or how long he has practised it so we can be sure it does not degenerate over time and circumstances into a more sordid state than the present one he set out to extirpate. Things are easier said than done. What if we discard our current formation models and adopt his model, only to find ourselves in a worse state of affairs? What is the assurance or proof that his model is the panacea to the ills which bedevil our formation system? He empirically studied and researched the current formation models, but has he done same to critically evaluate his own techniques? Vocation boom is not poverty but parents religiousity. They send their favourite children to the minor seminaries as a gift to God, or to gain the honour of Mama Fada, Papa Fada, or to get good education. Teachers and churchious parents are fond of this. Also, some ex-seminarians do it to make reparation for leaving the seminary. They enter at the age of 10-12 years, nave. Like in infant baptism, their faith is the faith of theie parents. Like the author said, long years of formation will not improve the seminarian. For me, it makes them over-familiar with the sacred. It corrupts them. Over-formation, like the law of diminishing returns, now results in mal-formation. Seminarians who used to attend daily masses as mass servers hardly do so now.

Here lies another explanation for the difference between diocesans and religious. The diocesan, like in infant baptism, is a family/community vocation; the religious, like in adult baptism, is a personalized vocation. This has many implications in formation. Despite the harsh conditions in the seminary, the numbers hardly decrease much because although many would have loved to leave, but concerns about the feelings of family, friends, relatives, benefactors, etc, hold most seminarians back. Even in the bible, Samuels vocation was not due to his mothers poverty, but her faith and promise to offer this offspring of her prayers to God (cf. I Sam. chs 1-3). Thus, he endured the concomitant hardships like sleeping on the floor while Elis sons lounged about and fed themselves fat. That is why if you grant many seminarians U.S.A. visa, many would gladly take it and travel abroad to escape the anger and disappointments of parents, family; to to overcome the guilt of refusing to serve God by changing environment, like Jonah; to overcome the feeling of being a failure; to seek greener pastures; to improve is status and that of his family; to appease his disappointed family. So in this case the visa vs his desire to comply with the wishes of his family the seminarian chooses the former. Therefore, it is not really out of poverty that he stayed in the seminary. Also, the shorter the formation, the more serious, focused and enthusiastic the minister is. For a case study, observe these three groups: protestant pastors who merely attend a brief theological program; religious who mainly enter the seminary from secondary school or university; and diocesans who mainly enter from the minor seminaries. There is no gainsaying that their zeal, spirituality and effectiveness is also in that order. So, it is seen more where the duration of formation is less, and vice versa. Ironically, if minor seminaries were removed, infant vocations, which mainly produce immature priests would be reduced. This increase in the quantity of our seminarians would be an opportunity for increase in the quality of seminarians and priests. What we would then have is adult vocation, which tends to produce more mature vocationers. We would then have those who have been called and know how to answer the call rather than those who were thrown into it at a tender age and are still straining their ears to hear the call, just like Samuel and Eli when Samuel heard the call which was discerned by Eli. If they had been many there, it is not very likely that Samuel would have traced the source of the call to Eli. They would have thought one of the many others also receiving formation with him was making noise after lights-out. Thus, the fewer number, the more effective the action of the Holy Spirit in initiating, discerning, responding to, and living out the vocation.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Mission Catholicity - Holy Sees 5 Essential MarksDokument3 SeitenMission Catholicity - Holy Sees 5 Essential Marksapi-272379696100% (1)

- My Chapter in Latinos in Civic ActivismDokument22 SeitenMy Chapter in Latinos in Civic Activismdrlizrios100% (1)

- Vol 18 No 1 2008 International Research PapersDokument65 SeitenVol 18 No 1 2008 International Research PapersHectorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Declaration On The Relationship of The Church To Non-Christian ReligionsDokument3 SeitenDeclaration On The Relationship of The Church To Non-Christian Religionstinman2009Noch keine Bewertungen

- Gs 1557Dokument302 SeitenGs 1557sectubNoch keine Bewertungen

- Educ310 - Intro To Christian Education 2Dokument27 SeitenEduc310 - Intro To Christian Education 2api-235676891Noch keine Bewertungen

- Charism of The Congregation of The Holy CrossDokument5 SeitenCharism of The Congregation of The Holy CrossBárbara SilvaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dominus Iesus (PDF) - EnglishDokument28 SeitenDominus Iesus (PDF) - EnglishCatholic Inside100% (1)

- Caritas GuideDokument37 SeitenCaritas GuideOliver ZielkeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1996 Issue 1 - Greg Bahnsen: Apologist, Theonomist, Warrior, Friend - Counsel of ChalcedonDokument2 Seiten1996 Issue 1 - Greg Bahnsen: Apologist, Theonomist, Warrior, Friend - Counsel of ChalcedonChalcedon Presbyterian ChurchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pious Association SeminarDokument10 SeitenPious Association SeminardinoydavidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Baptist in The BahamasDokument2 SeitenBaptist in The BahamasAlexis FergusonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Air4orce ArticleDokument3 SeitenAir4orce ArticleKenneth Masong100% (1)

- Biblical Perspectives Signature AssignmentDokument7 SeitenBiblical Perspectives Signature Assignmentapi-348371121Noch keine Bewertungen

- A Comparative Study of Christian Baptism Vis-A-Vis... Circ... TattooDokument30 SeitenA Comparative Study of Christian Baptism Vis-A-Vis... Circ... TattooGabriel LopezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philosophy of Ministry PaperDokument8 SeitenPhilosophy of Ministry Paperapi-284040279Noch keine Bewertungen

- Darren McDonald - My StoryDokument6 SeitenDarren McDonald - My StoryDarren McDonaldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Self ComportmentDokument4 SeitenSelf ComportmentOSONDU JUDE THADDEUSNoch keine Bewertungen

- Uka OmuDokument3 SeitenUka OmuOSONDU JUDE THADDEUS100% (1)

- William Cooper - Operation MajorityDokument6 SeitenWilliam Cooper - Operation Majorityvaneblood1100% (4)

- Invoice: Olga Ioan BLD - DACIEI, BL.40/853, AP.42, PARTER, SC.D Giurgiu România, Giurgiu, 224678Dokument2 SeitenInvoice: Olga Ioan BLD - DACIEI, BL.40/853, AP.42, PARTER, SC.D Giurgiu România, Giurgiu, 224678Schindler OskarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Macedonians in AmericaDokument350 SeitenMacedonians in AmericaIgor IlievskiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2002 Issue 1 - On Heresy - Counsel of ChalcedonDokument1 Seite2002 Issue 1 - On Heresy - Counsel of ChalcedonChalcedon Presbyterian ChurchNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1989 Issue 6 - Chalcedon Christian School Graduates First Class - Counsel of ChalcedonDokument2 Seiten1989 Issue 6 - Chalcedon Christian School Graduates First Class - Counsel of ChalcedonChalcedon Presbyterian ChurchNoch keine Bewertungen

- National Black Catholic Congress - Preamble To Pastoral Plan of ActionDokument2 SeitenNational Black Catholic Congress - Preamble To Pastoral Plan of ActionNational Catholic ReporterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Skills Needed For Celibacy-Martin Pable OFMCapDokument9 SeitenSkills Needed For Celibacy-Martin Pable OFMCapRaúl Saiz Rodríguez100% (1)

- 2008 Issue 5-6 - Women in The Church - Counsel of ChalcedonDokument9 Seiten2008 Issue 5-6 - Women in The Church - Counsel of ChalcedonChalcedon Presbyterian ChurchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thoughts From FR Alberione 1Dokument27 SeitenThoughts From FR Alberione 1MargaretKerryfsp100% (2)

- Bishop Jose Gomez's Statement On The Release of Clergy FilesDokument1 SeiteBishop Jose Gomez's Statement On The Release of Clergy FilesNational Catholic ReporterNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1989 Issue 7 - The Family in Its Offices of Instruction and Worship - Counsel of ChalcedonDokument3 Seiten1989 Issue 7 - The Family in Its Offices of Instruction and Worship - Counsel of ChalcedonChalcedon Presbyterian ChurchNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1990 Issue 7 - The Christian Vision of Victory: ACTS Seminar Review - Counsel of ChalcedonDokument10 Seiten1990 Issue 7 - The Christian Vision of Victory: ACTS Seminar Review - Counsel of ChalcedonChalcedon Presbyterian ChurchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Short Term Missions DependencyDokument5 SeitenShort Term Missions Dependencytjohnson365Noch keine Bewertungen

- A Theology of Political Vocation: Christian Life and Public OfficeVon EverandA Theology of Political Vocation: Christian Life and Public OfficeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Method in Dogmatic Theology: Protology (First Revelatory Mystery at Creation) To Eschatology (Last RedemptiveDokument62 SeitenMethod in Dogmatic Theology: Protology (First Revelatory Mystery at Creation) To Eschatology (Last RedemptiveefrataNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sustaining The Reformed Witness and Mission of The Presbyterian Church of NigeriaDokument7 SeitenSustaining The Reformed Witness and Mission of The Presbyterian Church of NigeriaGodswill M. O. UfereNoch keine Bewertungen

- Method, Motivation and Trinitarian Thinking in Jürgen Moltmann PDFDokument19 SeitenMethod, Motivation and Trinitarian Thinking in Jürgen Moltmann PDFstefan pejakovićNoch keine Bewertungen

- Folk Catholicism and Pre SpanishDokument17 SeitenFolk Catholicism and Pre SpanishMichael DalogdogNoch keine Bewertungen

- IBMTE Handbook, 2001 Edition - Chapter IV.Dokument5 SeitenIBMTE Handbook, 2001 Edition - Chapter IV.Jared Wright (Spectrum Magazine)Noch keine Bewertungen

- 043 Schwartz, Is There A Cure For Dependency Among MissionDokument8 Seiten043 Schwartz, Is There A Cure For Dependency Among MissionmissionsandmoneyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chaplaincy in GhanaDokument8 SeitenChaplaincy in GhanaAnthony Kpetsey100% (1)

- Augustine Was in The Forefront Against DonatismDokument12 SeitenAugustine Was in The Forefront Against DonatismAlfonsolouis HuertaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Infographic - Dialogue With CultureDokument2 SeitenInfographic - Dialogue With CultureRUSHELLE INTIA100% (1)

- Adventist Muslim Relations: John 10:16 Arumansi JohnDokument26 SeitenAdventist Muslim Relations: John 10:16 Arumansi JohnArumansi JNoch keine Bewertungen

- Measuring Spiritual Maturity: A Process to Move People from Spiritual Babies to Spiritual AdultsVon EverandMeasuring Spiritual Maturity: A Process to Move People from Spiritual Babies to Spiritual AdultsNoch keine Bewertungen

- College Uneducation by BocoboDokument2 SeitenCollege Uneducation by BocoboAnonymous gdQOQzV30DNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ecclesiology From Disabled PerspectiveDokument6 SeitenEcclesiology From Disabled PerspectiveBenison MathewNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1995 Issue 1 - How Many Times Can A Man Turn His Head and Pretend He Just Doesn't See? - Counsel of ChalcedonDokument3 Seiten1995 Issue 1 - How Many Times Can A Man Turn His Head and Pretend He Just Doesn't See? - Counsel of ChalcedonChalcedon Presbyterian ChurchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Beating the Bounds: A Symphonic Approach to Orthodoxy in the Anglican CommunionVon EverandBeating the Bounds: A Symphonic Approach to Orthodoxy in the Anglican CommunionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Through Middle Eastern Eyes: A Life of Kenneth E. BaileyVon EverandThrough Middle Eastern Eyes: A Life of Kenneth E. BaileyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Role of the Laity In the Administration and Governance of Ecclesiastical Property: Canons of the Eastern Orthodox ChurchVon EverandThe Role of the Laity In the Administration and Governance of Ecclesiastical Property: Canons of the Eastern Orthodox ChurchBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Prayer Letter Aug - 2021Dokument2 SeitenPrayer Letter Aug - 2021scottandnikkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Doncec Formetur: Where Did It Come From?Dokument33 SeitenDoncec Formetur: Where Did It Come From?Sister Anne Flanagan100% (2)

- Religious Extortion Among Pastors in NigeriaDokument5 SeitenReligious Extortion Among Pastors in NigeriaGodswill M. O. UfereNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reflection - Public Theology As Christian WitnessDokument2 SeitenReflection - Public Theology As Christian WitnesswilmerEC100% (1)

- Child TheologyDokument36 SeitenChild TheologyCatherine SNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transitive Cultures: Anglophone Literature of the TranspacificVon EverandTransitive Cultures: Anglophone Literature of the TranspacificNoch keine Bewertungen

- Partners in Wisdom and Grace: Catechesis and Religious Education in DialogueVon EverandPartners in Wisdom and Grace: Catechesis and Religious Education in DialogueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theological ClarityDokument91 SeitenTheological ClarityJohn FieckNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Mission of The Holy Spirit in The Daily Lives of ChristiansDokument26 SeitenThe Mission of The Holy Spirit in The Daily Lives of ChristiansLuis MendezNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2006 03 02 EquippedParticipantNBDokument83 Seiten2006 03 02 EquippedParticipantNBFabiano Silveira MedeirosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why Thomas Aquinas Distrusted IslamDokument3 SeitenWhy Thomas Aquinas Distrusted IslamVienna1683Noch keine Bewertungen

- RE-103 Church and Sacraments: Shaina Rosewell M. Villarazo Bsma 2Dokument38 SeitenRE-103 Church and Sacraments: Shaina Rosewell M. Villarazo Bsma 2Shaina Rosewell M. Villarazo100% (1)

- 1996 Issue 6 - The Queen of Days: Properly Observing The Sabbath Part 2 - Counsel of ChalcedonDokument4 Seiten1996 Issue 6 - The Queen of Days: Properly Observing The Sabbath Part 2 - Counsel of ChalcedonChalcedon Presbyterian ChurchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Development of Chinese Church Leaders: A Study of Relational Leadership in Contemporary Chinese ChurchesVon EverandDevelopment of Chinese Church Leaders: A Study of Relational Leadership in Contemporary Chinese ChurchesNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Teacher As A Role ModelDokument1 SeiteThe Teacher As A Role ModelOSONDU JUDE THADDEUSNoch keine Bewertungen

- Necessity of The SacramentsDokument3 SeitenNecessity of The SacramentsOSONDU JUDE THADDEUS100% (1)

- The Concept of Ogbanje in Igbo TraditionDokument3 SeitenThe Concept of Ogbanje in Igbo TraditionOSONDU JUDE THADDEUSNoch keine Bewertungen

- Things Left UnsaidDokument10 SeitenThings Left UnsaidOSONDU JUDE THADDEUSNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Role of Women in The ChurchDokument2 SeitenThe Role of Women in The ChurchOSONDU JUDE THADDEUS100% (1)

- The Church and Education in NigeriaDokument2 SeitenThe Church and Education in NigeriaOSONDU JUDE THADDEUS100% (3)

- The Relevance of The Pastoral Epistles To The Nigerian SituationDokument4 SeitenThe Relevance of The Pastoral Epistles To The Nigerian SituationOSONDU JUDE THADDEUSNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Role of Women in The SocietyDokument4 SeitenThe Role of Women in The SocietyOSONDU JUDE THADDEUS100% (1)

- The Parable of The PipelineDokument1 SeiteThe Parable of The PipelineOSONDU JUDE THADDEUS100% (1)

- The Metaphysics of Names and Referents in Igbo Cultural MilieuDokument3 SeitenThe Metaphysics of Names and Referents in Igbo Cultural MilieuOSONDU JUDE THADDEUSNoch keine Bewertungen

- Commentary On Palm SundayDokument3 SeitenCommentary On Palm SundayOSONDU JUDE THADDEUS100% (2)

- Form CriticismDokument1 SeiteForm CriticismOSONDU JUDE THADDEUSNoch keine Bewertungen

- MotivationDokument2 SeitenMotivationOSONDU JUDE THADDEUSNoch keine Bewertungen

- Crisologo Vs SingsonDokument1 SeiteCrisologo Vs SingsonJessette Amihope CASTORNoch keine Bewertungen

- Castle On The HillDokument6 SeitenCastle On The HillEmilia Scarfo'Noch keine Bewertungen

- 1038Dokument34 Seiten1038Beis MoshiachNoch keine Bewertungen

- Central Azucarera de Tarlac G.R. No. 188949Dokument8 SeitenCentral Azucarera de Tarlac G.R. No. 188949froilanrocasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Topic-Act of God As A General Defence: Presented To - Dr. Jaswinder Kaur Presented by - Pulkit GeraDokument8 SeitenTopic-Act of God As A General Defence: Presented To - Dr. Jaswinder Kaur Presented by - Pulkit GeraPulkit GeraNoch keine Bewertungen

- 20) Unsworth Transport V CADokument2 Seiten20) Unsworth Transport V CAAlfonso Miguel LopezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Crimes of The Century - Top 25 - Time MagazineDokument28 SeitenCrimes of The Century - Top 25 - Time MagazineKeith KnightNoch keine Bewertungen

- Accomplishment Report SPGDokument7 SeitenAccomplishment Report SPGJojo Ofiaza GalinatoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Locked RoomDokument3 SeitenThe Locked RoomNilolani JoséyguidoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sales Final ReviewerDokument4 SeitenSales Final ReviewerPhilipBrentMorales-MartirezCariagaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Soriano Vs PeopleDokument5 SeitenSoriano Vs PeopleSamantha BaricauaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dodging Double Jeopardy: Combined Civil and Criminal Trials Luis Garcia-RiveraDokument35 SeitenDodging Double Jeopardy: Combined Civil and Criminal Trials Luis Garcia-RiveraFarhad YounusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 5Dokument7 SeitenChapter 5Adrian SalazarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dator v. Carpio MoralesDokument5 SeitenDator v. Carpio MoralesPaolo TellanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 39 Clues Discussion QuestionsDokument2 Seiten39 Clues Discussion Questionsapi-26935172850% (2)

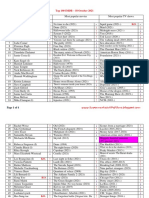

- Top 100 IMDB - 18 October 2021Dokument4 SeitenTop 100 IMDB - 18 October 2021SupermarketulDeFilmeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 79) DraftDokument167 Seiten79) DraftSaakshi BhavsarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Belgian Overseas Vs Philippine First InsuranceDokument6 SeitenBelgian Overseas Vs Philippine First InsuranceMark Adrian ArellanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- D Citizens CharterDokument5 SeitenD Citizens CharterGleamy SoriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Section Ii: Captains and Masters of VesselsDokument9 SeitenSection Ii: Captains and Masters of VesselsGeanelleRicanorEsperonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Romeo EssayDokument3 SeitenRomeo Essayapi-656725758Noch keine Bewertungen

- Operasi Lalang 2Dokument6 SeitenOperasi Lalang 2Zul Affiq IzhamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Penalty CardsDokument3 SeitenPenalty CardsAguilar France Lois C.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lunod Vs MenesesDokument2 SeitenLunod Vs MenesesPetallar Princess LouryNoch keine Bewertungen

- History of AliagaDokument5 SeitenHistory of AliagaCucio, Chadric Dhale V.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Significance of Black History MonthDokument6 SeitenSignificance of Black History MonthRedemptah Mutheu MutuaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chambertloir Biblio DefDokument8 SeitenChambertloir Biblio DefmesaNoch keine Bewertungen