Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Peri-Urbanization - Zones of Rural-Urban Transition

Hochgeladen von

Vijay KrsnaOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Peri-Urbanization - Zones of Rural-Urban Transition

Hochgeladen von

Vijay KrsnaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

9/12/12

PERI-URBANIZATION: ZONES OF RURAL-URBAN TRANSITION

INSTITUTIONAL AND INFRASTRUCTURAL RESOURCES - SAMPLE CHAPTERS

PERI-URBANIZATION: ZONES OF RURAL-URBAN TRANSITION

Douglas Webster, Asia Pacific Research Center, Stanford University, United States, and Larissa Muller, Department of City and Regional Planning, University of California at Berkeley, United States Keywords: Philippines, China, Thailand, peri-urbanization, exurban, suburbanization, edge city, hyperurbanization, exurbanization Contents 1. Peri-Urbanization 2. Peri-Urbanization in East Asia: Comparative Context 3. Chinese Peri-Urbanization 4. The Case of the HangzhouNingbo Corridor 5. Conclusions Acknowledgments Related Chapters Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketches Summary This contribution examines the emerging phenomenon of peri-urbanization. It analyses key drivers, dynamics, and outcomes of peri-urbanization, indicating how peri-urbanization manifests itself differently in cross-country contexts. The first section provides an overview of peri-urbanization processes world-wide. Next, the analysis focuses on East Asia. Two models of peri-urbanization that have emerged in Southeast Asia, the Thai and the Philippines model, are briefly described. Then, through an in-depth case study of the Hangzhou-Ningbo Corridor, the evolution of coastal peri-urbanization in China is discussed. The analysis focuses on the severe stressesdemographic, social, and environmentalaccompanying peri-urbanization, and identifies adaptive responses, successful and otherwise, to address them. 1. Peri-urbanization The term peri-urbanization refers to a process, often a highly dynamic one, in which rural areas located on the outskirts of established cities become more urban in character. This transformation occurs in physical, economic, and social terms, and often in piecemeal fashion. Peri-urban development usually involves rapid social change, as small agricultural communities are forced to adjust to an urban or industrial way of life in a very short time. High levels of in-migration are an important driver of social change. Rapid environmental deterioration and infrastructure backlogs are usually another characteristic of the peri-urban landscape. Typically, peri-urbanization is stimulated by an infusion of new investment, generally from outside, including foreign direct investment (FDI).

www.eolss.net/eolsssamplechapters/c14/e1-18-02/e1-18-02-txt.aspx 1/10

9/12/12

PERI-URBANIZATION: ZONES OF RURAL-URBAN TRANSITION

In spatial terms, Rakodi defines the peri-urban area as: "the transition zone between fully urbanized land in cities and areas in predominantly agricultural use. It is characterized by mixed land uses and indeterminate inner and outer boundaries, and typically is split between a number of administrative areas." The peri-urban zone begins just beyond the contiguous built-up urban area and sometimes extends as far as 150 kilometer (km) from the core city, or as in the Chinese case, as far as 300 km. The land that can be characterized as peri-urban shifts over time as cities, and the transition zone itself, expands outward. What frequently results is a constantly changing mosaic of both traditional and modern land use. Peri-urbanization does not necessarily result in an end state that resembles conventional urban or suburban communities. Because so much land is involved, and effective land use guidance systems are virtually non-existent in many countries, it appears that a semi-equilibrium that is neither totally urban nor suburban will result in many cases. Key characteristics of the peri-urbanization process, particularly in developing countries, include: Changing economic structure, encompassing a shift from an agriculturally based to a manufacturing dominated economy; Changing employment structure, shifting from agriculture to manufacturing; Rapid population growth and urbanization, a phenomenon often not captured in official data because the populations of peri-urban regions tend to be significantly under-countedin many countries, in-migrants do not officially register as local residents. Many peri-urban areas, furthermore, are still defined as rural, contributing significantly to an undercount of the urban population. Changing spatial development patterns and rising land costs. This highly eclectic and sometimes chaotic pattern of growth produces a monumental public agenda. The pattern of peri-urbanization is often determined initially by the routes of newly built highways, but little of the subsequent growth is properly planned or regulated. A great deal of land speculation is typical, and a boom town atmosphere prevails in which unfettered change outpaces efforts to organize it. Frequently, in developing countries, the requirements of the burgeoning local population for urban infrastructure, housing, medical services, and education are not adequately met. Environmental degradation proceeds rapidly. Industrial enterprises often have to resort to their own private infrastructure to guarantee adequate water, power, and other needs. In those periurban areas where in-migration from distant locales is significant, and the ratio of newcomers to long-term residents shifts radically, community building can be a major challenge. Where expectations of employment attract more job seekers than can be accommodated, or where the local poor are left behind, there also emerges in extended urban regions a need to refocus poverty prevention and alleviation efforts to the peri-urban zone. 1.1. Drivers The trend towards the dispersal of population and employment to the peripheries of metropolitan cities is becoming a world-wide phenomenon, but the drivers tend to differ. Large-scale investment, especially in manufacturing, is usually the trigger that sets off peri-urbanization. Often foreign direct investment is the driver, but in some cases, such as China, domestic investment is more significant. Peri-urban regions are attractive to foreign and domestic investment for two main reasons. First, peri-urban regions offer large, relatively inexpensive, land plots and less hindered freight transportation, especially by truck, in support of just-in-time production processes. The need for

www.eolss.net/eolsssamplechapters/c14/e1-18-02/e1-18-02-txt.aspx 2/10

9/12/12

PERI-URBANIZATION: ZONES OF RURAL-URBAN TRANSITION

large land plots is reinforced by investor and government preferences to group manufacturing firms in industrial estates. Industrial estates, especially high quality estates, lessen negative environmental impacts and facilitate government monitoring. These estates also provide locators with reliable infrastructure, spatial clustering of suppliers, often one-window approval services, and an intermediary, or buffer, in dealing with government officials and service providers. At the same time, peri-urban locations enable relatively easy access, usually within a 2.5 hour drive, to a major city that offers advanced producer and personal services, and access to major government decisionmakers. A second driver of peri-urbanization is public policy explicitly supporting dispersal of manufacturing away from core, and even suburban, areas. Generally the underlying rationale for these policies is to ease truck traffic, pollution, and reduce the risk of large-scale industrial accidents from manufacturing activities, in the core city. Given the large-scale capital spending involved, and thus their political sensitivity, public policies in support of peri-urbanization are often justified in terms of regional development objectives, i.e., dispersal of employment opportunities, and improvements to the quality of urban life associated with de-industrialization of core cities. Public investment support for peri-urbanization usually includes the provision of large-scale infrastructure, such as ports, highways, rail links, telecommunication facilities, water reservoirs, container handling facilities, airports, and sometimes, publicly-owned industrial estates. These infrastructure investments, usually delivered by national governments, either through line agencies or state enterprises, are often funded through international borrowing. Increasingly, public authorities attempt to attract private investors to fund these large projects through mechanisms such as BuildOperate-Transfer. Industrial location incentive packages are usually also a component of the public policy package. Such incentives generally take the form of tariff and corporate tax reductions to investors for a specified period of time, and often include an immigration policy component to enable expatriates to work as high level managerial and technical staff in the industries attracted to the peri-urbanizing areas. The precise nature of peri-urbanization public policies vary among countries and over time within countries (see Section 3 for more details of variation in East Asia). A striking feature common to most peri-urban areas in developing countries, however, is the lack of sufficient investment in social facilities, city building, and environmental infrastructure. For example, about 88% of cumulative public investment to 1999 in Thailands flagship Eastern Seaboard peri-urban region has been utilized for "production support infrastructure". Frequently high quality regional plans will be developed for peri-urban areas that include proposals for quality community developments, e.g., new towns, but expected private and public sector investment often does not materialize as planned. Another driver of peri-urbanization is the availability of relatively inexpensive labor, both in situ, in rural areas that are being enveloped by peri-urbanization, and in-migrants, particularly from poor regions in the countries in question, seeking employment opportunities. Migration dynamics can be either from rural to urban or step-wise from smaller towns and cities. There is wide variation in the mix of migrant versus in situ labor employed in peri-urban areas in different countries with very significant implications for public policy and potential local conflict. Because of labor mobility, the importance of local labor availability is less important than the availability of qualified labor at virtually all skill levels within the country in question that is willing to relocate to peri-urban areas. Daily commutes from the urban core are not possible for the vast majority of labor, especially production workers, because of the long travel times. When labor migration to these regions exceeds employment opportunities, as in the case of the extended Manila region, it frequently leads

www.eolss.net/eolsssamplechapters/c14/e1-18-02/e1-18-02-txt.aspx 3/10

9/12/12

PERI-URBANIZATION: ZONES OF RURAL-URBAN TRANSITION

to hyper-urbanization. Residential development can also act as a driver of peri-urbanizationthis process is termed suburbanization, or in cases where it jumps further out from the core, exurbanization. Middle and upper-middle class groups seeking more space at an affordable price, may purchase, and live in residences in peri-urban areas even though they do not work in the area. This driver is most important where peri-urbanization is found relatively close to the core city, or where core city personal security concerns are high, such as in Manila, Jakarta, and Johannesburg. Large property developers, often single-handedly shape peri-urban localities by building large integrated residential complexes comprising several gated housing developments catering to a range of incomes, and new commercial centers to service them. These gated communities, situated in peri-urban green fields, are essentially privately financed new towns. Public policy to relocate slum settlements out of the center city, or to relocate rural communities for large projects, such as dams, is another important driver of peri-urbanization, e.g., in Chongqing, China. Public housing, or suitable sites and services, are not always provided, prompting settlement in fragile, and frequently dangerous, areas, such as wetlands or steep slopes. Relocation decisions rarely take into consideration the availability of employment opportunities and social services. Thus, where population relocation policies are an important factor in the peri-urbanization process, the informal sector tends to play a much more significant role in the peri-urban economy, and access to social services by migrant populations is usually inadequate. 1.2. Global Variants While peri-urban patterns are broadly similar, variation in the relative importance, or absence, of different drivers, how these drivers are processed by local institutions, and the socio-economic contexts in which they occur, produce different types of processes and outcomes. The following identifies five major cross-continental variants in peri-urbanization, resulting from differential drivers, economic systems, demographic conditions, and other historical development factors. Variations also occur within each region, as section 3 illustrates. (i) Africa: Metropolitan areas in most parts of Africa, but also some parts of South Asia, are economically marginalized, having been bypassed by global growth and technological diffusion. For example, in 1998, South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa attracted about 5 billion U.S. (United States) dollars each in FDI, compared with about 60 billion dollars each to East Asia and Latin America. As a result, the urban spatial patterns of even the largest cities in Africa have not evolved much beyond the traditional urban form. Modern urban functions are still largely confined to the center, creating mono-centric urban regions that display declining density gradients in direct relationship with distance from the city center. In Africa, peri-urbanization is driven to a much greater extent by rural migration, or hyper-urbanization, stemming from push factors such as landlessness, agricultural unemployment, resettlement, and insecurity in some rural areas. Agricultural employment, such as market gardening and farm work, and the informal economy, remain significant sources of work for migrants to African peri-urban areas. (ii) North America: The edge city is a relatively new peri-urban phenomenon that has emerged in the last 15 years in the metropolitan regions of North America, particularly in the coastal urban regions. Edge city dynamics differ from peri-urbanization in developing countries in two respects. First, its economy is based on services, office, and commercial activities, not manufacturing. Second, although situated in outer suburbia, the edge city is politically, economically, and commercially independent of the central city. Its independence influences flows of commuters,

www.eolss.net/eolsssamplechapters/c14/e1-18-02/e1-18-02-txt.aspx 4/10

9/12/12

PERI-URBANIZATION: ZONES OF RURAL-URBAN TRANSITION

information, goods, etc. For example, commuter flows increasingly tend to be among outer nodes, i.e. cross-commuting, rather than to and from the core city. Surprisingly, the edge city phenomenon has not arisen to any significant extent in the extended urban regions of East Asia. High value services have stayed in the core city to a much greater extent in East Asia than in North America or Europe. This is the case despite public policy attempts to disperse high value service activity in urban regions, such as Hong Kong. This, however, may change. Tokyo has long had satellite centers driven by service activity and the edge city dynamics appear to be emerging in the Beijing extended urban region. Much farther out from the central cities, often 50 to 100 kilometers, well beyond suburbia, are industrial belts which more closely resemble the peri-urban zones in East Asia. Examples would include automobile manufacturing in Ohio and southern Ontario, and industrial developments along the I-85 motorway in the south-east United States. The drivers behind the dispersal and location of manufacturing to these peripheral areasa process that American researchers have dubbed exurban industrializationare similar to the ones driving the East Asian phenomenon. Because industrialization is in relative decline in developed countries, while high values services are in ascendancy, North American exurban industrialization, in the form of industrial belts, has not attracted as much research and policy attention as emerging post-industrial urban forms and dynamics, such as the edge city. (iii) Asia: Peri-urbanization in the emerging economies of Asia, especially Southeast Asia and selected areas of coastal China, is largely foreign-investment induced, in a process that Sit and Yang refer to as exo-urbanization. This model is based on labor-intensive, mass assembly, exportoriented industrialization. Seoul, an early case of peri-urbanization in East Asia, is a notable exception as its export-oriented industrialization has been generated by domestic rather than foreign investment, given that nations mercantilist policies during much of the second half of the twentieth century. Public policy, based on a combination of location incentives and investment in key public infrastructure projects catering to industry, is typically influential in encouraging industrial investment outside the core city, its suburbs, and its original manufacturing belts. At the same time as this, industrialization is inducing rapid urbanization and creating economic growth in these regions, it is also increasing social inequalities and environmental problems that, left unaddressed, can eventually bring the validity of the export-led development model into question. A unique feature commonly associated with Southeast Asian peri-urbanization is desakota, a term coined by McGee. This term describes corridor development consisting of an intense mixture of agriculture, cottage industry, industrial estates, residential development, and other uses co-existing side-by-side. It typically occurs in zones that were previously characterized by dense agricultural populations, usually engaged in rice cultivation, such as in the case of Bangkok, Thailand, and Jakarta, Indonesia. It has features distinguishable from situations where the core is situated in lightly populated regions of plantation agriculture, as in the case of Kuala Lumpur in Malaysia. There are indications, however, that the desakota pattern is less persistent than originally thought. In the case of extended Manila, there is strong empirical evidence that agriculture is being "squeezed out" of former desakota regions, a process that appears to be directly related to the labor absorption capacity of manufacturing, urban trade, and service sectors. (iv) Latin America: Peri-urbanization in Latin America, once the standard example of hyperurbanization, is being shaped by a new set of drivers. Having already reached very high levels of urbanization, rural to urban migration has virtually ended in Latin American countries. Suburbanization, including the relocation of slum communities, and to a much lesser extent, stepwise migration from smaller towns and cities, has become the principle drivers of residential periwww.eolss.net/eolsssamplechapters/c14/e1-18-02/e1-18-02-txt.aspx 5/10

9/12/12

PERI-URBANIZATION: ZONES OF RURAL-URBAN TRANSITION

urbanization. The dualism of the core city is carrying over into peri-urban areas. Thus Latin American peri-urban patterns are characterized by the segregation of lower-income populations in the more vulnerable peripheral areas, away from privileged, gated residential developments of the middle class. The Sao Paolo and Santiago extended urban regions epitomize this model. Manila is an interesting hybrid of the Latin American and East Asian casesa reflection of shared historical influences with Latin America, having been a colony of Spain and then America, which shaped many of its institutions. (v) Transnational Metropolitan Regions: A new variant of peri-urbanization is occurring along borders, where the core city of the extended metropolitan region is located in one country, and its peri-urban region is situated across the border in another. These transnational urban regions are driven by differential factor endowments between countries such as Hong Kong and Guangdong in Southern China, between Singapore, Johore, Malaysia and the Riau Islands, Indonesia, and between the southern USA and Mexico, where maquiladoras have arisen on the Mexican side of the border. A massive influx of FDI flows across the border into these peri-urban regions, fuels dramatic rates of both economic and demographic growth as employment opportunities, arising from this investment, attract significant numbers of migrants to the border region. McGee refers to this pattern of spatial growth in East Asia, as "the expanded city-state model," but as the USMexican and the Pearl River Delta cases illustrate, it is factor complementarities, more than the spatial constraints of city-states, that drive the process. Where factor differentials between neighboring countries are greatest, this cross-border peri-urbanization is often the most dynamic, provided cross-border flows of capital and goods are politically endorsed. 1.3 Whats at Stake? Particular characteristics of developing peri-urban regions make the stakes, given the wide possible variations in outcomes, especially high. These include: (i) Ladders of upward mobility. Manufacturing employment, predominantly located in peri-urban areas, is more accessible to those with moderate levels of educational achievement. Accordingly, peri-urban employment systems are important ladders of upward mobility, especially for inmigrants. Core cities, by contrast, are increasingly associated with high level tertiary employment with high credential barriers to entry on one hand, and insecure, formal and informal, low-level service sector jobs on the other. As a result, peri-urban economies have the potential to contribute significantly to poverty prevention and alleviation. (ii) National competitiveness. Peri-urban areas are at the intersection of globalization and localization forces. A relatively small number of extended urban regions exert disproportionate influence in terms of national competitivenesswell beyond what would be expected, even given their significant gross domestic product (GDP) and demographic shares. This is particularly the case in East Asia. Thus to an increasing extent, extended urban regions (EURs), including their vast periurban areas, are critical in determining national competitiveness, and related national well-being. (iii) Environmental deterioration. Manufacturing activities, and the settlement patterns associated with peri-urbanization, are not environmentally benign. Given the very rapid and high magnitude of demographic, economic, and manufacturing output growth in these areas, the risks of continuing, or even accelerating, environmental degradation are high. Local environmental damage reduces human well-being and public health, decreases the attractiveness of these areas for investment in high value activities, can reduce agricultural output, and damages the long-term integrity of local agroecological zones. Given the scale of major peri-urban areas, environmental impacts can transcend

www.eolss.net/eolsssamplechapters/c14/e1-18-02/e1-18-02-txt.aspx 6/10

9/12/12

PERI-URBANIZATION: ZONES OF RURAL-URBAN TRANSITION

the local, being continental or even global, in impact, e.g. acid rain impacts from coastal peri-urban development in China. (iv) Institutional fragmentation and rural-oriented administration. Decentralization and local government capacity building are current public policy priorities in many developing countries. Some of the highest stakes in decentralization outcomes, both in terms of potential damage and benefits, are found in peri-urban areas. Highly fragmented, frequently low capacity, and ruraloriented local governance in much of developing countrys peri-urban areas mean that decentralization, which leads to significant changes in the functions of local governments, will have disproportionate impacts. Peri-urban areas currently face severe challenges in terms of environmental degradation, including land conversion, employment creation, and social service delivery. The extent to which increasingly empowered local governments can address these challenges in peri-urban areas will significantly determine the well-being of hundreds of millions of people. Of particular concern are cases where decentralization processes are leading senior governments, both national and provincial, to abandon traditional coordination and large-scale investment roles in peri-urban areas. If empowered local governments cannot fill the gap, which is often the case, then the results will not be positive. (v) Rural-Urban Linkages. Peri-urban areas play an important role in terms of rural-urban interdependencea process of increasing concern because of its potential to vitalize rural areas. Peri-urban areas, as transition zones, play a vital role in linking urban and rural areas. Rural labor increasingly migrates to peri-urban areas rather than to urban. Remittances and people, through cyclical migration, constantly flow between rural and peri-urban areas. Rural people use peri-urban areas as staging areas and learning systems in rural-urban transition processes. Farmers in periurban areas frequently pioneer high value agricultural systems, because of market access and economic pressures related to the high value of land. Last, but not least, with their large populations, peri-urban areas will increasingly wield political powera new constituency neither rural nor urban. 2. Peri-Urbanization in East Asia: Comparative Context We now focus on peri-urbanization in East Asia. This region is of key interest for several reasons. First, it accounts for a substantial share of the population being added to peri-urban regions in the next quarter century. Peri-urban areas in East Asia will accommodate approximately 215 million of the expected 500 million additional urban residents in the East Asian Region over the next 25 years, with the majority of this incremental growth occurring in China. It is estimated that 77%of the incremental growth in the Jakarta EUR, and 53% in the Bangkok EUR, over this period, will be in peri-urban areas. The pattern may be equally, if not more, pronounced for Chinese cities if the Tenth National Development Plan (2001-2006) policy to accelerate productive urbanization is successfully implemented. The policy objective is to raise annual urban population growth to 4%, an increase of at least 1% over current forecasts. This is a rapid rate of long term urban growth by both historical and contemporary standards, and if it is to be sustained, it will require a very substantial building up of the peri-urban interface around all Chinese metropolitan regions. There are currently at least 56 metropolitan areas in China with more than one million inhabitants. Second, the peri-urbanization processes underway in East Asia are highly dynamic ones. How periurbanization is managed is of critical importance in terms of future national economic development and the quality of life for hundreds of millions of people in East Asia. Developing East Asian periurban regions together constitute the emerging factory floor of the world, attracting most of the FDI

www.eolss.net/eolsssamplechapters/c14/e1-18-02/e1-18-02-txt.aspx 7/10

9/12/12

PERI-URBANIZATION: ZONES OF RURAL-URBAN TRANSITION

to developing countries, and replacing industrial ancestors such as the Midlands of Britain, the Ruhr region of Germany, the Great Lakes region of North America, and the Tokyo-Osaka corridor in Japan. As such, these regions will be the site of job creation numbering well in excess of 100 million. They are an integral and critical component of larger metropolitan systems, which account for the majority of national GDP in virtually every East Asian country. For example, over 80% of the manufacturing output, and over half the national GDP in Thailand is produced within the Bangkok EUR, with peri-urban areas accounting for over 25% and gaining share. Because variation in peri-urbanization occurs not only between regions, as discussed in section 2.3, but also within a region, it is difficult to generalize about East Asian peri-urbanization. Although the differences should not be overstatedmany of the drivers and issues are broadly similar, varying primarily in importancethe manner in which these dynamics interact and are mediated at the local level, produces features and outcomes that are unique to each peri-urban area. As a point of reference, and as a framework for policy development, it is useful to review two distinct models that have emerged in Southeast Asia before proceeding to the Chinese case study. These are the Thai Model and the Philippines Model. 2.1. The Thai Model Thailands Eastern Seaboard (ESB) is representative of the Thai model of peri-urbanization. The ESB is located to the east of Bangkok. Its furthest extension is about 190 kilometers from the core city. The area covers three provinces and contains approximately three million people. The two principal drivers of peri-urbanization in the ESB are FDI and national government policy. The economic dominance of manufacturing in ESB is among the highest in the worldaccounting for over 60% of the gross regional product (GRP), compared with less than 30% in the core Bangkok Metropolitan Administration area. The ESB represents a middle case of public sector involvement in initiation and ongoing coordination of peri-urbanization. The extent of government involvementin the Thai case this means the national governmentin ESB development was greater than in other Southeast Asian countries, but did not reach South Korean or Chinese levels. National government intervention involved investment in infrastructure including the construction of two world-class ports and an expressway system linking the ESB to Bangkok, generous industrial location incentives, and the creation of a specialized unit in the national planning agency to plan and coordinate the area. National government involvement is credited with moving the peri-urbanization dynamic much further from the urban core than is the case in most other East Asian extended urban regions. The two main factors accounting for this geographic outcome are the fact that (i) the two new major ports are remote from core Bangkok, and (ii) Thailands industrial incentive structure offered the highest industrial location incentives only in the ESB province most distant from Bangkok, Rayong. The Thai property development industry is not as concentrated as in other Southeast Asian countries. As a result, the property industry was not able to develop integrated communities that included industrial estates, residential communities, and commercial centers, similar to the ones that have emerged in peri-urban areas of Manila and Jakarta. Partially as a result of the failure of industrial and residential developers to coordinate their projects, a significant spatial disconnect between work and residence has developed. Commuting distances in the ESB extend up to 70 km a pattern that is effectively subsidized by employers through free bussing of workers to and from the factories. Local coordination and management of peri-urbanization in ESB is all but absent. This reflects the

www.eolss.net/eolsssamplechapters/c14/e1-18-02/e1-18-02-txt.aspx 8/10

9/12/12

PERI-URBANIZATION: ZONES OF RURAL-URBAN TRANSITION

high spatial fragmentation and low capacity of local governments in Thailand. Municipalities tend to have jurisdictional responsibility for areas smaller than the total urbanized area, so most of the industrial development and urbanization falls under the jurisdiction of some of the 450 plus small, inexperienced, rural oriented tambons in the ESB. Local management capacity is further limited by the absence of regional coordination mechanisms. Under the decentralization process that is currently underway in Thailand, tambons and municipalities report directly to senior governments (primarily the national government). This is very different from the nested local government structures in China and the Philippines where municipalities oversee lower level governments that cover peri-urban and rural areas within the EUR, i.e. barangays in the Philippines, and counties and townships in China. Given the structure and low capacity of local governments, adaptation to the peri-urbanization process at the local level has been largely instigated by the private sector, e.g. industrial estates subsidize and coordinate local traffic police, build feeder roads, and even organize and deliver social services such as worker health care insurance and counseling. Firms are active in training. Such adaptation, however, tends to be localized, i.e. be within geographic zones of direct interest to the private sector actor involved, and in the case of social services, almost invariably focuses on employees of the firm or industrial estate in question only. Local entrepreneurs are active in developing small-scale commercial facilities and providing housing, while participants in the informal sector play an important role in operating food stalls and transportation services, e.g. converted pickup trucks, outside industrial estates and residential areas. Few voluntary organizations, be they non-governmental organizations or community-based organizations, are active in the peri-urban area. As elsewhere in developing East Asia, the involvement of voluntary organizations beyond the urban core tends to lag behind the peri-urbanization of their target groups and emergence of new issues associated with peri-urbanization. 2.2. The Philippine Model The most intense peri-urbanization in the Philippines is occurring to the south of Metro Manila, in Cavite and Laguna Provinces, which is referred to as the CALA region and has a population of 3.8 million. The primary drivers of peri-urbanization are FDI in manufacturing, primarily in electronic products which accounts for over 60% of the Philippines exports by value, and residential development. Gated and walled residential communities in peri-urban Manila attract populations who are willing to commute long distances, at considerable time expense, into core Manila. This reflects the amenities available in Laguna Province, including an attractive landscape of lakes and volcanic hills, and the fact that Manila is increasingly perceived as an insecure place to live. High population growth rates in the area, topping 7% annually near investment clusters, can also be attributed to high natural population increase, large-scale migration from rural to peri-urban areas, and the official resettlement of squatters from Metro Manila to the CALA region. The role of the national government in planning, promoting, and coordinating peri-urban development in the Philippines is by far the weakest in East Asia. This reflects the nations struggling fiscal situation and political realities, such as the perceived need to funnel investment to southern areas, such as Mindanao, to reduce separatist pressures. The result is very poor regional infrastructure within CALA. Critical bottlenecks include failure to upgrade key transportation corridors, including rail commuter systems, and expand Batangas port, south of CALA. The latter development would reorient some traffic flows, particularly cargo, southward. Traffic congestion, associated with infrastructure bottlenecks, has constrained peri-urban development spatially. The CALA peri-urban area is contained within a 50 km radius of Metro Manila, yet travel times to the core city can be equivalent to 150 kilometer journeys between ESB and core Bangkok.

www.eolss.net/eolsssamplechapters/c14/e1-18-02/e1-18-02-txt.aspx 9/10

9/12/12

PERI-URBANIZATION: ZONES OF RURAL-URBAN TRANSITION

Infrastructure bottlenecks, furthermore, have constrained economic development in the region, e.g. FDI applications slowed by 60% in 2000. It appears, however, that conditions may have reached bottom in CALA. As of mid-2001 new transportation investments are being approved for CALA, including busways that can be upgraded to light rail transit lines, and FDI investment applications appear to be trending upward. Having started the decentralization process earlier than other Southeast Asian countries, the strength of Philippines municipalities have compensated in part for the significant under involvement of the national government, and the two Provincial governments, in coordinating the development of CALA. Since the Local Government Code of 1991 came into effect, giving the Philippine municipalities and cities a wide array of powers and functions, the Philippines local governments have succeeded in implementing several pro-active initiatives within their own jurisdictions. These include technical training relevant to entry-level positions in nearby multinational corporations factories; low income housing provision, particularly for local government employees; top-ups to local health and education budgets; and local traffic improvement. Coordination and planning for much needed regional facilities, such as solid waste disposal, feeder road systems linked to freeways, and mass public rapid transport, however, has been lacking, given the passive role of provincial governments, which tend to focus on police and judicial activities, and the national government, which lacks fiscal resources. A second factor partially compensating for the lack of national government involvement in periurban development in the Philippines is the existence of a few large property development companies, with substantial financial, planning, and management competencies that are capable of developing integrated communities in peri-urban areas. In this regard, Manila is similar to the Jakarta extended region where private developers play a very significant role in developing the periurban region. Their involvement increasingly extends into the traditionally public realm, such as donating land for public projects, and even taking responsibility for delivering and maintaining trunk infrastructure. For example, the Ayala Land Corporation is about to commence construction of a key access road from one of their industrial estates to the Laguna-Manila expressway to eliminate current gridlock on the local road. Ayala Land also has proposed an initiative to buy the rail line from Manila southwards along Laguna Lake to provide commuter rail transportation and freight service to a string of Ayala-developed, peri-urban communities and the existing communities en route. In other respects, the adaptation processes are quite similar to the ESB situation. The tenants associations in industrial parks develop and manage social programs for local industrial employees. Local entrepreneurs and workers in the informal sector have responded to opportunities resulting from peri-urban development processes. Although the Philippines is known for its large number of non-governmental organizations, perhaps more per capita than anywhere in the world, they are only slightly more active in Manilas peri-urban area than in Bangkoks. One area of significant difference, and a potential asset to the Philippines, is the large-scale involvement of the Philippines private sector in delivering technical education, through hundreds of private colleges, particularly in fast growing areas such as computer programming. 3. Chinese Peri-Urbanization

Copyright 2004 Eolss Publishers. All rights reserved. SAMPLE CHAPTERS

www.eolss.net/eolsssamplechapters/c14/e1-18-02/e1-18-02-txt.aspx

10/10

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Development Economics Urban RuralDokument11 SeitenDevelopment Economics Urban Ruralshabrina larasatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Concept of Urban SprawlDokument4 SeitenConcept of Urban SprawlSiddharth MNoch keine Bewertungen

- 0015 1947 Article A011 enDokument4 Seiten0015 1947 Article A011 enamjad sjahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lec 05 Urban GrowthDokument10 SeitenLec 05 Urban GrowthM Khuram ishaqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 5 - Urbanization - ADokument38 SeitenModule 5 - Urbanization - AAlyssa AlejandroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Urban Development: Promoting Jobs, Upgrading Slums, and Developing Alternatives To New Slum FormationDokument5 SeitenUrban Development: Promoting Jobs, Upgrading Slums, and Developing Alternatives To New Slum Formationkristina41Noch keine Bewertungen

- Migration and Urbanization PDFDokument12 SeitenMigration and Urbanization PDFArnel MangilimanNoch keine Bewertungen

- RM 1 Urban Transport and Urban FormDokument11 SeitenRM 1 Urban Transport and Urban FormSyed Talha AhmedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Land Development, Administration and Law I. Land Development 1. Definitions: Land DevelopmentDokument43 SeitenLand Development, Administration and Law I. Land Development 1. Definitions: Land DevelopmentbruNoch keine Bewertungen

- Poor Master Plan For Low Income Housing Integrating Urban Design PhilippinesDokument3 SeitenPoor Master Plan For Low Income Housing Integrating Urban Design PhilippinesChester James FabicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Urban Geography NotesDokument22 SeitenUrban Geography Noteskowys8871% (7)

- Advantages of UrbanizationDokument42 SeitenAdvantages of UrbanizationJagadish Chandra Boppana87% (15)

- Result Resume of Book Compact Cities by Inna Syani PertiwiDokument11 SeitenResult Resume of Book Compact Cities by Inna Syani PertiwiDidik BandiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Urban SprawlDokument7 SeitenUrban SprawlApril AnneNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7 - WB Urbanization KP Full DocumentDokument18 Seiten7 - WB Urbanization KP Full DocumentNikhil SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ConclusionDokument4 SeitenConclusionRoshni KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- ECO 343 Chapter 10 FA 23Dokument9 SeitenECO 343 Chapter 10 FA 23alfie.hyettNoch keine Bewertungen

- Urban GrowthDokument20 SeitenUrban GrowthRica Angela LapitanNoch keine Bewertungen

- ALLAM Y JONES Attracting Investment by Introducing The City As A Special Economic ZoneDokument8 SeitenALLAM Y JONES Attracting Investment by Introducing The City As A Special Economic ZoneDiego RoldánNoch keine Bewertungen

- Planning-Theories 2Dokument40 SeitenPlanning-Theories 2jbcruz2Noch keine Bewertungen

- 414 Urp 4141 1and 2Dokument7 Seiten414 Urp 4141 1and 2benitoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Truta Ingrid+Panainte Rares - Urbat Revitalization and GentrificationDokument11 SeitenTruta Ingrid+Panainte Rares - Urbat Revitalization and GentrificationIngrid HaleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eco 225 2022 Lecture Note 1 - IntroDokument5 SeitenEco 225 2022 Lecture Note 1 - IntroeldenpotNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strateg Sustenabilit PDFDokument36 SeitenStrateg Sustenabilit PDFJorz AuguNoch keine Bewertungen

- New State Formation in MoroccoDokument4 SeitenNew State Formation in MoroccoHajira Anjum100% (1)

- Planning and Development of Urban Settlements in Respect of Spontaneous GrowthDokument20 SeitenPlanning and Development of Urban Settlements in Respect of Spontaneous GrowthnymipriyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- SPRAWL Vs SMART GROWTHDokument9 SeitenSPRAWL Vs SMART GROWTHrama_subrahmanianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Geography and Development - FullDokument25 SeitenGeography and Development - FullsantirossiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Simone - Uncertain Rights To The CityDokument5 SeitenSimone - Uncertain Rights To The CityThais FelizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complex Infrastructure Projects: A Critical PerspectiveVon EverandComplex Infrastructure Projects: A Critical PerspectiveBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1)

- CE104 HRE Lecture 2 Development and Planning Part 1Dokument9 SeitenCE104 HRE Lecture 2 Development and Planning Part 1ESCARO, JOSHUA G.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 5 1Dokument46 SeitenChapter 5 1Amul ShresthaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bangalore PaperDokument8 SeitenBangalore Paperrama_subrahmanianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lessons From World Development Report Int'l Comm OrgDokument4 SeitenLessons From World Development Report Int'l Comm OrgAankit SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ge4 Written Report Group 3Dokument4 SeitenGe4 Written Report Group 3ICAO JOLINA C.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Forum 8 - CanlasDokument2 SeitenForum 8 - CanlasPauline CanlasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nber Working Paper SeriesDokument44 SeitenNber Working Paper SeriesJesse LesmanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Urbanization and Rural-Urban Migration: Theory and Policy: by Group 3Dokument40 SeitenUrbanization and Rural-Urban Migration: Theory and Policy: by Group 3ARYAT100% (2)

- Urban Underground SpaceDokument9 SeitenUrban Underground Spaceekaastika100% (1)

- Strateg SustenabilitDokument36 SeitenStrateg SustenabilitpartyanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Economic Impact Farmland ConversionDokument25 SeitenEconomic Impact Farmland ConversionSmriti SNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To Urban PlanningDokument77 SeitenIntroduction To Urban PlanningAMANUEL WORKUNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Drives Infrastructure Spending in Cities of Developing Countries?Dokument25 SeitenWhat Drives Infrastructure Spending in Cities of Developing Countries?Iris Joy CaneteNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2 Assignment On Rural Urban Linkage For Rural Development AbdelaDokument5 Seiten2 Assignment On Rural Urban Linkage For Rural Development AbdelaHagos AbrahaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 1 V2Dokument26 SeitenChapter 1 V2Momentum PressNoch keine Bewertungen

- Factors Affecting Land Use PatternsDokument5 SeitenFactors Affecting Land Use PatternsKaruri John100% (2)

- Unit 5Dokument17 SeitenUnit 5Honeylette MolinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 7 Urbanization and Rural-Urban Migration - Theory and PolicyDokument22 SeitenChapter 7 Urbanization and Rural-Urban Migration - Theory and PolicyFurqan Waris67% (3)

- Globalization and Urban Governance in Two Asian Cities - Pune (India) and Cebu (The Philippines)Dokument15 SeitenGlobalization and Urban Governance in Two Asian Cities - Pune (India) and Cebu (The Philippines)kkNoch keine Bewertungen

- No.1: How To Improve Rural-Urban Linkages To Reduce PovertyDokument4 SeitenNo.1: How To Improve Rural-Urban Linkages To Reduce PovertyGlobal Donor Platform for Rural DevelopmentNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Perils of Urban Regeneration in Colombos Slave IslandDokument19 SeitenThe Perils of Urban Regeneration in Colombos Slave IslandtanzilarchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impacts of Urbanization On Economy PrintDokument16 SeitenImpacts of Urbanization On Economy PrintChaitali ShroffNoch keine Bewertungen

- Migration Impact On REAL ESTATEDokument3 SeitenMigration Impact On REAL ESTATESameer SrivastavaNoch keine Bewertungen

- AssignmentDokument71 SeitenAssignmentrishi guptaNoch keine Bewertungen

- HOUSING BARCH Question Paper AnsweringDokument27 SeitenHOUSING BARCH Question Paper AnsweringSandra BettyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 8 - Rural - Urban InteractionDokument15 SeitenChapter 8 - Rural - Urban InteractionfiraytaamanuelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impact of UrbanizationDokument11 SeitenImpact of Urbanizationpatel krishnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Urbanization and RuralDokument3 SeitenUrbanization and RuralHazell DNoch keine Bewertungen

- Volume 51, Issue 3, P. 434-440Dokument7 SeitenVolume 51, Issue 3, P. 434-440Abdul KadirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ar 4123Dokument1 SeiteAr 4123Vijay KrsnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evironmental Management C 1, B 1Dokument4 SeitenEvironmental Management C 1, B 1Vijay KrsnaNoch keine Bewertungen

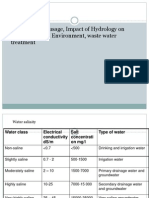

- Brackish Water Usage, Impact of Hydrology On Landscapes and Environment, Waste Water TreatmentDokument82 SeitenBrackish Water Usage, Impact of Hydrology On Landscapes and Environment, Waste Water TreatmentVijay KrsnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Waste RecyclingDokument13 SeitenWaste RecyclingVijay KrsnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Provisional Population Totals 2011 Karnataka ReportDokument28 SeitenProvisional Population Totals 2011 Karnataka ReportsilkboardNoch keine Bewertungen

- Keybord ShorkeyDokument6 SeitenKeybord ShorkeyAkshay Agrawal100% (1)

- The Cavite Mutiny 1872Dokument10 SeitenThe Cavite Mutiny 1872Mark Gil100% (7)

- Chinese Connection, Agrarian Relations & Friar Lands and Interclergy Conflicts & Cavite MutinyDokument23 SeitenChinese Connection, Agrarian Relations & Friar Lands and Interclergy Conflicts & Cavite MutinyJemimah MalicsiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Digest Assignment As of Feb 15 2023Dokument3 SeitenCase Digest Assignment As of Feb 15 2023Joshua CapispisanNoch keine Bewertungen

- RizalDokument8 SeitenRizalJazon Valera50% (2)

- World Teachers' Day Simultaneous Municipal Kick - Off AttendanceDokument5 SeitenWorld Teachers' Day Simultaneous Municipal Kick - Off AttendanceGilbert Mores EsparragoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cavite MutinyDokument22 SeitenCavite MutinyK100% (4)

- Best Places To Go Visit Ilocos Norte and SurDokument174 SeitenBest Places To Go Visit Ilocos Norte and SurRoseAnnPletadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Name Signature Position Date: Designation of School Planning TeamDokument3 SeitenName Signature Position Date: Designation of School Planning TeamGianne Azel Gorne Torrejos-SaludoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arañas - Reaction-Paper - Massive Balangay 'Mother Boat' Unearthed in ButuanDokument5 SeitenArañas - Reaction-Paper - Massive Balangay 'Mother Boat' Unearthed in ButuanSweet ArañasNoch keine Bewertungen

- EDUC 3. Chapter 1Dokument22 SeitenEDUC 3. Chapter 1JENEFER GUADALQUIVERNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Philippine Ethnic Tradition DanceDokument13 SeitenThe Philippine Ethnic Tradition DanceChucky B. Bugallon100% (1)

- Poli Cases From Election CasesDokument4 SeitenPoli Cases From Election CasesApple ObiasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Canonical AuthorsDokument2 SeitenCanonical AuthorsAlexis Keith Bontuyan91% (11)

- Building Directory Metro ManilaDokument12 SeitenBuilding Directory Metro ManilaRose CuraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Biography of Author, F. Sionil Jose: Sunday MagazineDokument8 SeitenBiography of Author, F. Sionil Jose: Sunday MagazineMau De JesusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesspn 3: 21St Century Literary Genres Elements, Structures and TraditionsDokument8 SeitenLesspn 3: 21St Century Literary Genres Elements, Structures and TraditionsAlex Abonales DumandanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ge 9: The Life and Works of Rizal: Republic of The Philippines University Town, Northern SamarDokument14 SeitenGe 9: The Life and Works of Rizal: Republic of The Philippines University Town, Northern SamarJezza Mae Gomba RegidorNoch keine Bewertungen

- STS PPT Chapter 2Dokument38 SeitenSTS PPT Chapter 2Kenneth Rodriguez HerminadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dinalupihan, BataanDokument2 SeitenDinalupihan, BataanSunStar Philippine NewsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Development of Visual Arts in The PhilippinesDokument40 SeitenDevelopment of Visual Arts in The PhilippinesKristela Mae ColomaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Organizational Structure of The Department of Education Field - 093508Dokument13 SeitenOrganizational Structure of The Department of Education Field - 093508Aira Mae MambagNoch keine Bewertungen

- Professional Education 9 The Teacher and The School CurriculumDokument11 SeitenProfessional Education 9 The Teacher and The School CurriculumshielaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Directory of CRM DestinationDokument220 SeitenDirectory of CRM DestinationGlen MacadaegNoch keine Bewertungen

- Is There A Filipino PsychologyDokument10 SeitenIs There A Filipino PsychologyMARK ANTHONY CARABBACANNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sectoral Dev't Plan. PTESD Plan 2010-2013Dokument205 SeitenSectoral Dev't Plan. PTESD Plan 2010-2013Alenton AnnalynNoch keine Bewertungen

- About AngonoDokument10 SeitenAbout AngonoPatrick FernandezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contemporary ArtsDokument3 SeitenContemporary ArtsJhonabie Suligan CadeliñaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Edited Certificate of Completion in Work ImmersionDokument21 SeitenEdited Certificate of Completion in Work Immersionfrederick sorianoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marquez Module 2Dokument2 SeitenMarquez Module 2Ron-Ron S. MarquezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marvin Lagonera - Curriculum VitaeDokument7 SeitenMarvin Lagonera - Curriculum VitaeMarvin LagoneraNoch keine Bewertungen