Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

KSHV Forgotten But Not Gone

Hochgeladen von

Edwin J. Alvarado-RodriguezOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

KSHV Forgotten But Not Gone

Hochgeladen von

Edwin J. Alvarado-RodriguezCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

From bloodjournal.hematologylibrary.org by guest on July 31, 2012. For personal use only.

2011 117: 6973-6974 doi:10.1182/blood-2011-05-350306

KSHV: forgotten but not gone

Patrick S. Moore and Yuan Chang

Updated information and services can be found at: http://bloodjournal.hematologylibrary.org/content/117/26/6973.full.html Information about reproducing this article in parts or in its entirety may be found online at: http://bloodjournal.hematologylibrary.org/site/misc/rights.xhtml#repub_requests Information about ordering reprints may be found online at: http://bloodjournal.hematologylibrary.org/site/misc/rights.xhtml#reprints Information about subscriptions and ASH membership may be found online at: http://bloodjournal.hematologylibrary.org/site/subscriptions/index.xhtml

Blood (print ISSN 0006-4971, online ISSN 1528-0020), is published weekly by the American Society of Hematology, 2021 L St, NW, Suite 900, Washington DC 20036. Copyright 2011 by The American Society of Hematology; all rights reserved.

From bloodjournal.hematologylibrary.org by guest on July 31, 2012. For personal use only.

inside blood

30 JUNE 2011 I VOLUME 117, NUMBER 26 CLINICAL TRIALS

Comment on Uldrick et al, page 6977

KSHV: forgotten but not gone ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Patrick S. Moore and Yuan Chang

UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH CANCER INSTITUTE

Thirty years ago, Kaposi sarcoma (KS) arose as a prominent manifestation of the AIDS epidemic. Seventeen years ago we discovered the virus that causes KS,1 Kaposi sarcomaassociated herpesvirus (KSHV), and within a year KSHV had been also shown to be the likely cause of AIDS-associated primary effusion lymphoma (PEL)2 and most cases of multicentric Castleman disease (MCD).3

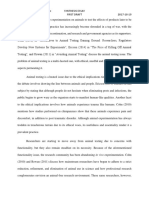

KSHV-infected cells expressing vIL-6 within an adventitious germinal center in a multicentric Castleman disease tumor. Illustration courtesy of C. Parravicini.

ince then, almost no progress has been made in treating the virus that causes these tumors. In this issue of Blood, for the rst time, Uldrick et al describe a long overdue approach to MCD therapy based on direct targeting of KSHV.4 There are now 7 known human cancer viruses but only scattered efforts to developed

drugs specically targeting them. The successes of the human papillomavirus and hepatitis B virus vaccines make clear that virusoriented therapies have the potential to be major success stories in cancer management. If a virus causes a tumor, why are most pharmaceuticals targeting the host cancer cell instead of the causative virus? The most impor-

tant reason is economics: 1 in 5 cancers worldwide has an infectious origin, with most cases concentrated in poor and developing countries. But to be fair to the pharmaceutical industry, drugs against viral cancers are also difcult to make. Almost all current antivirals target viral replication machinery. The most wellknown antiviral drug is acyclovir, a nucleoside analog activated by the herpes simplex thymidine kinase enzyme. This viral protein is only expressed during active viral replication to replicate viral DNA and for this reason acyclovir is effective against cold sores but not against latent virus in trigeminal or sacral ganglia. Acyclovir reduces symptoms but does not cure the underlying disease. Similarly, viruses in most tumor cells are latent as well. If viruses in cancer cells did actively replicate, host innate and adaptive immune responses would kill the cell before it could grow into a clinically apparent tumor, and for most viral cancers there is no target that can be hit with available drugs. Ganciclovir, for example, is remarkably effective in randomized clinical trials to prevent KSHV replication and KS5,6 but has no effect once KS tumors emerge.7 The study by Uldrick et al looks at this problem in a different wayare there any other KSHV-related tumors in which actively replicating virus can be targeted? Castleman disease is a B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder driven by IL-6 over-expression and in KSHV-related MCD, only a small percentage of tumor cells are actually KSHV-infected (see gure). KSHV-infected MCD cells are surrounded by uninfected B cells forced to multiply by cytokine-induced mitogenesis, which make up the bulk of MCD tumors and are responsible for most MCD symptoms and sequelae. Viral replication machinery plays a key role in MCD because KSHV-encoded vIL-6 is amplied as part of the viruss replication program (although the KSHV vIL-6 gene can be activated in different ways and should not be called a lytic KSHV gene).

6973

blood 3 0 J U N E 2 0 1 1 I V O L U M E 1 1 7 , N U M B E R 2 6

From bloodjournal.hematologylibrary.org by guest on July 31, 2012. For personal use only.

Uldrick et al exploit this to develop a viral chemotherapy regimen against MCD. The work extends previous studies suggesting that antivirals can improve MCD patient survival.8 In their pilot study, Uldrick et al use the ganciclovir prodrug, valganciclovir, together with zidovudine (AZT) to precisely target 2 viral enzymes involved in viral DNA synthesis, the viral phosphotransferase and thymidine kinase, respectivelya rst in KSHV oncology. These drugs can potentially be paired with other standard chemotherapies to further improve outcome for this disease that otherwise has a dismal prognosis. Both drugs are approved for human use with other viral infections having more favorable pharmaco-economic indices than KSHV. In some African countries hard hit by AIDS, however, Kaposi sarcoma accounts for the majority of adult cancers reported to cancer registries. In Southeast Asia, EBV-containing nasopharyngeal carcinoma is a major unmet public health problem. Despite the effectivenesss of papillomavirus vaccines, cervical cancer remains a major killer throughout the developing world, and 4000 women die from it annually in the US. For KSHV and most other cancer viruses, the problem is not that there is no possible viral drug target. KSHV latency-associated nuclear antigen 1 is needed by the virus to maintain its genome in every tumor cell. Finding drugs to target these latent viral proteins is more an economic than a scientic issue. In the words of the astronaut Gus Grissom, No bucks, no Buck Rogers. Rates of KS in developed countries have dramatically fallen with the development of effective antiretroviral therapy for HIV/ AIDS, reducing the urgency to develop new control approaches to KSHV tumors. The current respite in KSHV-related disease, however, may be only temporary. Antiretroviral therapy does not affect latent, life-long KSHV infections and so resurgence of KSHV-related tumors with aging of the current HIV/AIDS population can be expected. We have not used this quiet time wisely. This study by Uldrick et al provides a key lesson that antiviral chemotherapy in KSHV tumors can work but only because of MCDs unusual pathoetiology. MCD acts more like a smoldering virus infection than a neoplasm. If new classes of antivirals were to be developed targeting latent cancer virus oncoproteins, there is promise that remarkable

6974

clinical outcomes could emerge. These drugs could lead to cures instead of palliation for some viral infections. They might also be far less toxic than current cancer chemotherapies because they target foreign proteinsmuch like the miraculous antibiotics of the 1940s. The study reported in this issue Blood is an important rst step in this direction. Conict-of-interest disclosure: The authors hold patents related to KSHV that have been assigned to Columbia University.

REFERENCES

1. Chang Y, Cesarman E, Pessin MS, et al. Identication of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-associated Kaposis sarcoma. Science. 1994;265(5192):1865-1869. 2. Cesarman E, Chang Y, Moore PS, Said JW, Knowles DM. Kaposis sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-related body-cavity-based lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(18):1186-1191.

3. Soulier J, Grollet L, Oksenhendler E, et al. Kaposis sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in multicentric Castlemans disease. Blood. 1995;86(4): 1276-1280. 4. Uldrick TS, Polizzotto MN, Aleman K, et al. High-dose zidovudine plus valganciclovir for Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus-associated multicentric Castleman disease: a pilot study of virus-activated cytotoxic therapy. Blood. 2011; 117(26):6977-6986. 5. Martin DF, Kuppermann BD, Wolitz RA, Palestine AG, Li H, Robinson CA. Oral ganciclovir for patients with cytomegalovirus retinitis treated with a ganciclovir implant.N Engl J Med. 1999;340(14):1063-1070. 6. Casper C, Krantz EM, Corey L, et al. Valganciclovir for suppression of human herpesvirus-8 replication: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. J Infect Dis. 2008;198(1):23-30. 7. Krown SE, Dittmer DP, Cesarman E. Pilot study of oral valganciclovir therapy in patients with classic kaposi sarcoma. J Infect Dis. 2011;203(8):1082-1086. 8. Casper C, Nichols WG, Huang ML, Corey L, Wald A. Remission of HHV-8 and HIV-associated multicentric Castleman disease with ganciclovir treatment. Blood. 2004;103(5):1632-1634.

IMMUNOBIOLOGY

Comment on Barao et al, page 7032

Unlicensed natural born killers ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Andreas Lundqvist and Richard Childs

KAROLINSKA INSTITUTET; NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH

In this issue of Blood, Barao and colleagues describe repopulation of Ly49G2 single-positive NK cells after congenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) that appear fully functional, having tumor cytolytic capacity despite recipients lacking MHC molecules thought necessary to license them.

atural killer (NK) cells are innate lymphocytes capable of killing tumors and virus-infected cells. Their function is regulated through a variety of different receptors. In humans, the largest group of receptors belongs to the killer Immunoglobulin-like family, or KIRs. Although structurally different from KIRs, mice possess Ly49 receptors that share similar functional characteristics; both KIRs and Ly49 receptors are composed of members possessing inhibitory or activating properties that regulate the function of the NK cell on binding its cognate MHC class I ligand. Although cell subsets lacking inhibitory receptors for self-MHC have been observed in both man and mouse, in vitro studies have shown that these potentially autoreactive NK-cell populations are in most cases hyporesponsive. In contrast, NK cells whose inhibitory receptors interact with self-MHC class I acquire functional competence, a process referred to as licensing.1 Such licensed NK cells are immunologically competent and

are capable of responding to stimuli in vitro and in vivo. In this issue of Blood, Barao et al investigated whether licensing plays a role in the reconstitution of NK cells bearing different Ly49 receptors in mice undergoing HSCT.2 Initial experiments focused on transfer of bone marrow cells in congenic C57BL/6 mice (H-2b-positive). In these mice, Ly49G2 single-positive NK cells are considered unlicensed because of their inability to bind H2b. Contrary to expectations, early NK-cell repopulation after HSCT was dominated by Ly49G2 single-positive NK cells. Remarkably, these unlicensed NK cells were phenotypically mature and were not hyporesponsive, lysing tumor targets to a similar degree as licensed NK-cell controls. When experiments were repeated in mice on an H-2d background, a selective expansion of Ly49G2 singlepositive NK cells was again observed. Thus, it appears that NK-cell repopulation early after HSCT is dominated by Ly49G2 single30 JUNE 2011 I VOLUME 117, NUMBER 26

blood

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (894)

- The Drug That Cracked Covid by Michael CapuzzoDokument15 SeitenThe Drug That Cracked Covid by Michael CapuzzoAll News Pipeline0% (1)

- Siegfried's Death and Funeral MarchDokument7 SeitenSiegfried's Death and Funeral MarchEdwin J. Alvarado-RodriguezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Virology Learning TableDokument6 SeitenVirology Learning Table//Noch keine Bewertungen

- Bee Propolis PresentationDokument23 SeitenBee Propolis PresentationPERRYAMNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spatial Analysis With RDokument32 SeitenSpatial Analysis With REdwin J. Alvarado-RodriguezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Synthesis EssayDokument4 SeitenSynthesis EssayEdwin J. Alvarado-RodriguezNoch keine Bewertungen

- MycomedicinalsDokument51 SeitenMycomedicinalslightningice100% (1)

- CHN 1 Topic 1. A Handout in Overview of Public Health Nursing in The Phils.Dokument11 SeitenCHN 1 Topic 1. A Handout in Overview of Public Health Nursing in The Phils.DANIAH ASARI. SAWADJAANNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conductometric Determination of Sulfuric Acid in Battery FluidDokument28 SeitenConductometric Determination of Sulfuric Acid in Battery FluidEdwin J. Alvarado-RodriguezNoch keine Bewertungen

- World War IDokument7 SeitenWorld War IEdwin J. Alvarado-RodriguezNoch keine Bewertungen

- High-Dose Zidovudine Plus Valganciclovir For Kaposi SarcomaDokument11 SeitenHigh-Dose Zidovudine Plus Valganciclovir For Kaposi SarcomaEdwin J. Alvarado-RodriguezNoch keine Bewertungen

- JFugueDokument58 SeitenJFugueEdwin J. Alvarado-RodriguezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Avian Flu in South East AsiaDokument160 SeitenAvian Flu in South East AsiaMaria Sri PangestutiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Therapeutic Drug Classes ExplainedDokument3 SeitenTherapeutic Drug Classes ExplainedFrank GomesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Treatment Algorithm For Managing Chronic Hepatitis B VirusDokument10 SeitenTreatment Algorithm For Managing Chronic Hepatitis B VirusRadhaRajasekaranNoch keine Bewertungen

- BIOLOGYDokument18 SeitenBIOLOGYRavi KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Antiviral AgentsDokument14 SeitenAntiviral Agentsalishba100% (1)

- Antiviral Drugs Aspects of Clinical Use and Recent AdvancesDokument206 SeitenAntiviral Drugs Aspects of Clinical Use and Recent AdvancesJosé RamírezNoch keine Bewertungen

- ISO 21702 - 2019 (En), Measurement of Antiviral Activity On Plastics and Other Non-Porous SurfacesDokument1 SeiteISO 21702 - 2019 (En), Measurement of Antiviral Activity On Plastics and Other Non-Porous SurfacesAnil Kumar Yadav0% (1)

- Fortune Vushe CH205 Assignment 1Dokument4 SeitenFortune Vushe CH205 Assignment 1Fortune VusheNoch keine Bewertungen

- Topical Anti-Infectives: Indications, Contraindications, Dosing & Side EffectsDokument12 SeitenTopical Anti-Infectives: Indications, Contraindications, Dosing & Side EffectsMabusiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Low-Cost Commercial Scale Production of SofosbuvirDokument333 SeitenLow-Cost Commercial Scale Production of SofosbuvirJohn Patrick DagleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Homeopatie EchinaceeaDokument16 SeitenHomeopatie EchinaceeaelenasiraduNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Latest:: Veg. Vs Non-VegDokument44 SeitenThe Latest:: Veg. Vs Non-VegedwincliffordNoch keine Bewertungen

- Virus & Antiviral Drugs: Prof. Dr. Ishrat ImranDokument57 SeitenVirus & Antiviral Drugs: Prof. Dr. Ishrat Imransomi shaikh100% (1)

- Genomics BLAST Assignment analyzes H1N1 mutationsDokument12 SeitenGenomics BLAST Assignment analyzes H1N1 mutationsDaniel Suarez100% (1)

- Open Letter To The WHO: Immediately Halt All Covid-19 Mass Vaccinations-Geert Vanden Bossche, DMV, PDokument2 SeitenOpen Letter To The WHO: Immediately Halt All Covid-19 Mass Vaccinations-Geert Vanden Bossche, DMV, PNemo NemoNoch keine Bewertungen

- AP Bio F17 Immune System WebquestDokument3 SeitenAP Bio F17 Immune System WebquestClaire ParrishNoch keine Bewertungen

- North Mesquite High School Ms. Taylor's Biology ClassDokument51 SeitenNorth Mesquite High School Ms. Taylor's Biology Classapi-3277577450% (1)

- IRF7 in The Australian Black Flying FoxDokument13 SeitenIRF7 in The Australian Black Flying FoxRamon LopesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Print NCLEX Study - Mark Klimek Blue BookDokument17 SeitenPrint NCLEX Study - Mark Klimek Blue Booklento1990Noch keine Bewertungen

- Epidemiology and Infection PreventionDokument32 SeitenEpidemiology and Infection Preventionbkbaljeet116131Noch keine Bewertungen

- Đề Thi Học Sinh Giỏi Thành Phố Lớp 12 TP Hải Phòng Môn Tiếng Anh Bảng Không Chuyên 2019-2020Dokument4 SeitenĐề Thi Học Sinh Giỏi Thành Phố Lớp 12 TP Hải Phòng Môn Tiếng Anh Bảng Không Chuyên 2019-2020Ý Nguyễn Thị NhưNoch keine Bewertungen

- Discussion and ConclusionDokument4 SeitenDiscussion and ConclusionRisma WerdaningsihNoch keine Bewertungen

- MCQ Chemotherapy Cancer DrugsDokument11 SeitenMCQ Chemotherapy Cancer DrugsAyesha khanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Immune Responses To Influenza VirusDokument12 SeitenImmune Responses To Influenza Virusdavid onyangoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 0 Jir 298242 Coronil A Tri Herbal Formulation Attenuates Spike ProteinDokument16 Seiten0 Jir 298242 Coronil A Tri Herbal Formulation Attenuates Spike ProteinMohakNoch keine Bewertungen