Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

John Locke

Hochgeladen von

Carl RollysonOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

John Locke

Hochgeladen von

Carl RollysonCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Book Review Locke: A Biography by Roger Woolhouse The English philosopher John Locke (1632-1704) left behind not

only "An Essay Co ncerning Human Understanding" (1690) but also his laundry lists and many other r ecords, documents, and correspondence quite an abundant stock of material d enrich the work of his biographer. Roger Woolhouse draws deeply on this awesome archive, and yet to my biographer's mind, "Locke: A Biography" (Cambridge, 548 pages, $39.99) is a let-down. Follow ing the well-established procedures of academia, Mr. Woolhouse presents Locke's life in strict chronological order, paying heed to every treatise, even when the re is considerable overlap between these works resulting in tiresome repetitions . If this Locke scholar is obliged to be so rigidly faithful to the order of his s ubject's oeuvre, is there not a corresponding fealty to the demands of biography ? Certainly, Mr. Woolhouse lays bare a good deal about his subject, but he never lingers to take the measure of the man who argued that government is founded on the consent of the governed, and that the individual begins life as a piece of "white paper" on which experience writes his ideas and values. In his early writings, for example, Locke was doubtful that there could be comit y between different Christian denominations, let alone between different faiths. After traveling to Cleves in Germany and witnessing how a diverse community of Christians managed to live in harmony, he began to change his views, becoming, i n the end, an outspoken champion of toleration. Why not write, then, a Lockean biography? Instead of giving every piece of the p hilosopher's writing equal weight, focus precisely on those experiences that gav e rise to his treatises. And attach those experiences and works to the portrayal of a man with strikingly modern ideas about self-invention. When Locke rejected an opportunity to pursue a diplomatic post in Spain, he wrot e in a letter: "Whether I have let slip the minute that they say everyone has on ce in his life to make himself, I cannot tell." Step aside, Andy Warhol, for the original philosopher of self-creation. Locke observed himself learning from experience, and consequently he launched a series of arguments against the notion of innate ideas. The mind expanded throug h the senses. God gave humankind a sensory apparatus for a purpose, Locke conten ded, even if not everything in creation can be comprehended through empirical in vestigation. All this can be gleaned from Mr. Woolhouse's very learned book, but it becomes r ather a chore to assemble. And some aspects of Locke are never integrated into a whole view of the man. Why, for example, was Locke so interested in medicine an d chemistry? Surely his fascination with the functioning of the human body is co nnected to his fixation on a corporeal self, where ideas result from physical se nsations.

that shoul

Even more intriguing are Locke's chronic illnesses. He thought he had consumptio n (tuberculosis), although it now seems more probable that he suffered from asth ma, bronchitis, and eventually emphysema from inhaling all that horrid coal smok e in London. He almost never visited the city without returning home to Oxford w ith a racking cough. Did Locke see in his own ailments which interrupted but perha ps also stimulated his medical studies proof of the way ideas and sensations mesh? Mr. Woolhouse might object that evidence is lacking for the answers to my questi ons. But surely it is duty of any biographer to pose questions that arise out of

the patterns of a subject's life. Biography is not merely a matter of reporting what the biographer knows; it is a lso a work of interpretation seeking out the subject's motivations. For example, Mr. Woolhouse seems to think that Locke was rather cowardly when he disavowed t he politics of his employer, the Earl of Shaftsbury, who was suspected of plotti ng against Charles II. Locke had been Shaftsbury's secretary and was certainly p rivy to, if not a full participant in, Shaftsbury's intrigues. Mr. Woolhouse quo tes "someone who knew him [Locke] during his worrying years" as having a "peacea ble temper, and rather fearful than courageous." He might here have pointed out that Locke's aim was to preserve his life as a thinker, even if it meant to use Mr . Woolhouse's term resorting to "disingenuity." Experience taught Locke to bide his time. In 1699, he returned to England from a six-year exile in Holland, understanding that his new sovereign, William, would look favorably on his work. Thus began Locke's triumphant years of publication. So Locke did not miss his minute, and it is unfortunate that Mr. Woolhouse's bio graphy does not present his subject's grand return and triumph with the kind of fanfare it deserves.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- John Locke CompleteDokument16 SeitenJohn Locke CompleteJohn Paul Canlas SolonNoch keine Bewertungen

- HIST103 3.3.3 JohnLocke FINAL1Dokument5 SeitenHIST103 3.3.3 JohnLocke FINAL1JohnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Uzgalis Locke's EssayDokument148 SeitenUzgalis Locke's Essayulianov333Noch keine Bewertungen

- Study Guide to The Philosophy of Thomas Hobbes and John LockeVon EverandStudy Guide to The Philosophy of Thomas Hobbes and John LockeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Some Thoughts Concerning Education (SparkNotes Philosophy Guide)Von EverandSome Thoughts Concerning Education (SparkNotes Philosophy Guide)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Bloch, Ernst - Geoghegan, Vincent - Bloch, Ernst - Ernst Bloch-Routledge (1995 - 1996)Dokument220 SeitenBloch, Ernst - Geoghegan, Vincent - Bloch, Ernst - Ernst Bloch-Routledge (1995 - 1996)Sergio Guillermo Palencia FrenerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lutosławski, Wincenty, ''The World of Souls'', 1924.Dokument230 SeitenLutosławski, Wincenty, ''The World of Souls'', 1924.Stefan_Jankovic_83Noch keine Bewertungen

- Gypsy Rose LeeDokument3 SeitenGypsy Rose LeeCarl RollysonNoch keine Bewertungen

- John Locke 29 August 1632 - 28 October 1704) Was An English Philosopher and PhysicianDokument9 SeitenJohn Locke 29 August 1632 - 28 October 1704) Was An English Philosopher and PhysicianRo Lai Yah BerbañoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Asd Disability Resoure PaperDokument8 SeitenAsd Disability Resoure Paperapi-411947017Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Whole Art of Detection by William Lambert GardinerDokument10 SeitenThe Whole Art of Detection by William Lambert GardinerMichael Harrison ChopadeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Class 12th Chemistry Project On Investigatory Test On GuavaDokument20 SeitenClass 12th Chemistry Project On Investigatory Test On GuavaAyush Kumar100% (1)

- Ozomed BrochureDokument4 SeitenOzomed BrochurechirakiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Medieval Philosophy: A Practical Guide to William of OckhamVon EverandMedieval Philosophy: A Practical Guide to William of OckhamBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1)

- John LockeDokument12 SeitenJohn LockeFerrer BenedickNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philology of The Gospels, F.blassDokument266 SeitenPhilology of The Gospels, F.blassroland888100% (1)

- Atestat Engleza - Sherlock HolmesDokument16 SeitenAtestat Engleza - Sherlock HolmesVictor Năstase100% (1)

- Wing 1981 AspergerDokument15 SeitenWing 1981 Asperger__aguNoch keine Bewertungen

- John LockeDokument21 SeitenJohn LockeSamuelle Arden Papasin LacapNoch keine Bewertungen

- HIDROKELDokument22 SeitenHIDROKELfairuz hanifahNoch keine Bewertungen

- John LockeDokument7 SeitenJohn LockeJet LamisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter One: Historical Background of John LockeDokument21 SeitenChapter One: Historical Background of John LockeFarhan AmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Locke ReadingsDokument71 SeitenLocke ReadingsobrienmillaNoch keine Bewertungen

- John Locke: Emanuel KantDokument26 SeitenJohn Locke: Emanuel KantLazr MariusNoch keine Bewertungen

- John Locke ProjectDokument2 SeitenJohn Locke ProjectMichael WilkinsNoch keine Bewertungen

- TerkumaDokument25 SeitenTerkumaterna undeNoch keine Bewertungen

- With Others, and Out of This Contract Emerges OurDokument15 SeitenWith Others, and Out of This Contract Emerges OurBlanka ČičakNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Paper John LockeDokument5 SeitenResearch Paper John Lockewclochxgf100% (1)

- John Locke Act. 1Dokument2 SeitenJohn Locke Act. 1b.pares.cNoch keine Bewertungen

- John Locke Research PaperDokument6 SeitenJohn Locke Research Paperpukjkzplg100% (1)

- Assignment in Understanding The SelfDokument5 SeitenAssignment in Understanding The SelfJoel AldeNoch keine Bewertungen

- John Locke (1632-1704) : Theory of The StateDokument24 SeitenJohn Locke (1632-1704) : Theory of The StateMaraInesAlejandraNoch keine Bewertungen

- John LockeDokument2 SeitenJohn LockeJosell MulleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lockee PDFDokument12 SeitenLockee PDFNorafsah Awang KatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marc Bloch and The Historian's CraftDokument17 SeitenMarc Bloch and The Historian's Craftsverma6453832Noch keine Bewertungen

- John LockeDokument6 SeitenJohn Lockeeverie100% (1)

- John Locke YaleDokument22 SeitenJohn Locke Yalejames brettNoch keine Bewertungen

- Locke's Philosophy: Content and ContextDokument22 SeitenLocke's Philosophy: Content and ContextBerr WalidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Basic Facts About John LockeDokument7 SeitenBasic Facts About John LockeAriane Mae M. SudarioNoch keine Bewertungen

- John Locke: Theories of Religious ToleranceDokument3 SeitenJohn Locke: Theories of Religious ToleranceEya De VeraNoch keine Bewertungen

- No ManDokument2 SeitenNo ManJosell MulleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Robert BoyleDokument3 SeitenRobert BoyleJheamarys ArsolonNoch keine Bewertungen

- John Locke: (29 August 1632 - 28 October 1704)Dokument3 SeitenJohn Locke: (29 August 1632 - 28 October 1704)Princess Frean VillegasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Natural Rights Jhon LockeDokument13 SeitenNatural Rights Jhon Lockeswafwan yousafNoch keine Bewertungen

- John Lockes Contribution To EducationDokument12 SeitenJohn Lockes Contribution To EducationYenThiLeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rousseau in England: The Context for Shelley's Critique of the EnlightenmentVon EverandRousseau in England: The Context for Shelley's Critique of the EnlightenmentNoch keine Bewertungen

- Some Turns of Thought in Modern Philosophy - TextDokument134 SeitenSome Turns of Thought in Modern Philosophy - TextRosemberg SantosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journal of Philosophy, Inc. The Journal of PhilosophyDokument9 SeitenJournal of Philosophy, Inc. The Journal of PhilosophygangNoch keine Bewertungen

- History of English Thought in the Eighteenth Century, Volume 1 (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)Von EverandHistory of English Thought in the Eighteenth Century, Volume 1 (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Doctor in LiteratureDokument20 SeitenThe Doctor in Literatureamm1101Noch keine Bewertungen

- John Locke 1634-1704Dokument16 SeitenJohn Locke 1634-1704Seazan chyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hobbes 032323 MBPDokument280 SeitenHobbes 032323 MBPMusa MusaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Victorians Art and CultureDokument8 SeitenThe Victorians Art and CultureJana V ValachováNoch keine Bewertungen

- Francis Bacon Montesquieu Voltaire Jean Jacques Rousseau David Hume Adam SmithDokument10 SeitenFrancis Bacon Montesquieu Voltaire Jean Jacques Rousseau David Hume Adam SmithforeroshanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Portraits - Power and Glory Vis-a-Vis Form and ContentmentVon EverandPortraits - Power and Glory Vis-a-Vis Form and ContentmentNoch keine Bewertungen

- Justice Holmess PhilosophyDokument53 SeitenJustice Holmess PhilosophypbNoch keine Bewertungen

- SelfDokument9 SeitenSelfChristine Ann SongcayawonNoch keine Bewertungen

- UntitledDokument3 SeitenUntitledCarl RollysonNoch keine Bewertungen

- UntitledDokument3 SeitenUntitledCarl RollysonNoch keine Bewertungen

- UntitledDokument2 SeitenUntitledCarl RollysonNoch keine Bewertungen

- William Jennings BryanDokument2 SeitenWilliam Jennings BryanCarl RollysonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tillie OlsenDokument2 SeitenTillie OlsenCarl RollysonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Margaret SangerDokument1 SeiteMargaret SangerCarl RollysonNoch keine Bewertungen

- TolstoyDokument1 SeiteTolstoyCarl RollysonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Joseph SmithDokument2 SeitenJoseph SmithCarl RollysonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Beatrix PotterDokument2 SeitenBeatrix PotterCarl RollysonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Richard FeynmanDokument2 SeitenRichard FeynmanCarl RollysonNoch keine Bewertungen

- William F. Buckley Jr.Dokument1 SeiteWilliam F. Buckley Jr.Carl RollysonNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Slave in The White HouseDokument2 SeitenA Slave in The White HouseCarl RollysonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leon TrotskyDokument2 SeitenLeon TrotskyCarl RollysonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Margaret FullerDokument1 SeiteMargaret FullerCarl RollysonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Patricia HighsmithDokument1 SeitePatricia HighsmithCarl RollysonNoch keine Bewertungen

- James JoyceDokument1 SeiteJames JoyceCarl RollysonNoch keine Bewertungen

- George IIIDokument2 SeitenGeorge IIICarl RollysonNoch keine Bewertungen

- George SandDokument2 SeitenGeorge SandCarl RollysonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leni RiefenstahlDokument2 SeitenLeni RiefenstahlCarl RollysonNoch keine Bewertungen

- ToussaintDokument2 SeitenToussaintCarl RollysonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jerome RobbinsDokument2 SeitenJerome RobbinsCarl RollysonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adolf HitlerDokument2 SeitenAdolf HitlerCarl RollysonNoch keine Bewertungen

- George KennanDokument2 SeitenGeorge KennanCarl RollysonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ho Chi MinhDokument2 SeitenHo Chi MinhCarl RollysonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Belva LockwoodDokument2 SeitenBelva LockwoodCarl RollysonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Emerson & ErosDokument2 SeitenEmerson & ErosCarl RollysonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ernest JonesDokument2 SeitenErnest JonesCarl RollysonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ho Chi MinhDokument2 SeitenHo Chi MinhCarl RollysonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Perioperative Preparation and Management: Pre-OperativeDokument14 SeitenPerioperative Preparation and Management: Pre-OperativeRed StohlNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Study 416Dokument34 SeitenCase Study 416jennifer_crumm100% (1)

- Apraxia of Speech and Grammatical Language Impairment in Children With Autism Procedural Deficit HypothesisDokument6 SeitenApraxia of Speech and Grammatical Language Impairment in Children With Autism Procedural Deficit HypothesisEditor IJTSRDNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vaccine HesitancyDokument2 SeitenVaccine HesitancyFred smithNoch keine Bewertungen

- Peds 2015-3501 Full PDFDokument19 SeitenPeds 2015-3501 Full PDFJehan VahlepyNoch keine Bewertungen

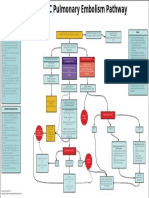

- EMCrit Lae Pulmonary FlowDokument1 SeiteEMCrit Lae Pulmonary FlowhmsptrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Warming Center New HavenDokument3 SeitenWarming Center New HavenHelen BennettNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Anatomy & Physiology: Chapter 21-1Dokument103 SeitenHuman Anatomy & Physiology: Chapter 21-1AngelyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reviewer Nutrimonth QuizbeeDokument47 SeitenReviewer Nutrimonth QuizbeeDale Lyko AbionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Inggris 201Dokument5 SeitenInggris 201hakimzainulNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dosage Chapter 1 PDFDokument4 SeitenDosage Chapter 1 PDFLena EmataNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Review On Herbal Drugs Used in The Treatment of COVID-19.Dokument15 SeitenA Review On Herbal Drugs Used in The Treatment of COVID-19.Samiksha SarafNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fatty Liver and Cirrhosis - DR GurbilasDokument7 SeitenFatty Liver and Cirrhosis - DR GurbilasDr. Gurbilas P. SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- 04-15-21 Covid-19 Vaccine TrackerDokument52 Seiten04-15-21 Covid-19 Vaccine TrackerJohn Michael JetiganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gouty Arthritis Health TeachingDokument14 SeitenGouty Arthritis Health TeachingnesjynNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gen Bio 2 Q4 Module 4Dokument25 SeitenGen Bio 2 Q4 Module 4Shoto TodorokiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lab 1C PAR-Q and Health History QuestionnaireDokument4 SeitenLab 1C PAR-Q and Health History Questionnaireskyward23Noch keine Bewertungen

- A Simple Approach To Shared Decision Making in Cancer ScreeningDokument6 SeitenA Simple Approach To Shared Decision Making in Cancer ScreeningariskaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Paper - B Written Test Paper For Selection of Teachers: CSB 2013 English (PGT) : Subject Code: P11Dokument4 SeitenPaper - B Written Test Paper For Selection of Teachers: CSB 2013 English (PGT) : Subject Code: P11Amrit SinhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adr Enaline (Epinephrine) 1mg/ml (1:1000) : Paediatric Cardiac Arrest AlgorhytmDokument13 SeitenAdr Enaline (Epinephrine) 1mg/ml (1:1000) : Paediatric Cardiac Arrest AlgorhytmwawaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Giardia M.SC PDFDokument18 SeitenGiardia M.SC PDFRahul ChaudharyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acute MI DMII Medical ManagementDokument52 SeitenAcute MI DMII Medical ManagementsherwincruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lapsus Dr. DodyDokument36 SeitenLapsus Dr. DodyPriscilla Christina NatanNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Biological Profile For Diagnosis and Outcome of COVID-19 PatientsDokument10 SeitenA Biological Profile For Diagnosis and Outcome of COVID-19 PatientsAristidesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Behavior & Crisis ManagementDokument74 SeitenHuman Behavior & Crisis ManagementJvnRodz P GmlmNoch keine Bewertungen