Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Doing and Knowing: Personal Perception

Hochgeladen von

Abhey RanaOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Doing and Knowing: Personal Perception

Hochgeladen von

Abhey RanaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Doing and knowing

Personal perception Subjective experience Unmixed light Life and learning Impartiality 1 1 3 4 5

Personal perception As persons in the world, we do things with our bodies, our senses and our minds. Thus, through our physical and sensual and mental capabilities, we interact with objects that we think about and see. But what about our consciousness? What sort of capability is it? What is the knowing that we do through it? We usually think of consciousness as a personal caFigure 1 Knowing island pability, whose knowing is a personal activity towards the objects that are known. But this activity of physical and sensual and mental knowing gives K N O W N us a curiously distorted picture of the world. Each person is then pictured, in her or his own view, as a knowing island of personal experience, surrounded KNOWING by a known world. Figure 1 shows an illustration. PERSON The evident distortion here is that the knowing personality is given far too much importance, as the centre of the world. Seen from this apparent centre, W O R L D our views of world get personally coloured and distorted, by partialities of personality. When the world is examined objectively, some of our distortions are questioned and discarded, through further pictures of the world that are developed by objective science. However, such objective pictures have problems of their own. They are each built from limiting assumptions, which makes them specialized. The more a picture is built up objectively, the more specialized it gets. So there is an inherent problem of putting the specializations together. For that, and to correct mistaken assumptions, we sometimes do reflect from our objective pictures, into a more direct experience that is essentially subjective. Subjective experience What happens when experience is examined subjectively? There too, a questioning is possible, to uncover and correct mistakes. In particular, we can ask how far its true that knowing is a personal activity. For a start, is knowing an activity of body? Do our bodies and their brains know anything themselves? From a subjective point of view, the answer is no, not quite. Our bodies and brains are physical objects, interacting with other such objects. That interaction is not knowledge in itself, but only a means of knowing. Each body is only a physical instrument. As things are experienced subjectively, they are not known by anyones body, but only through it. So this body cannot be the subjective centre of anyones experience.

Ananda Wood http://sites.google.com/site/advaitaenquiry/ woodananda@gmail.com

2 Then what about our senses? Do they know anything themselves? Again, not quite. Through our bodily interactions with objects, the senses form perceptions, which appear in mind. Our senses are thus instruments, producing sights, sounds, odours, flavours and sensations of touch, which our minds interpret as perceptions of objects. In our subjective experience, things are not known by any faculty of sense, but only through it. No such faculty can be the centre of subjective experience. And what about our minds? How do we know things here? As we investigate our mental experience, a rather different picture of how we know appears. Here, no surrounding world is seen, around a knowing body. In the experience of our minds, no one sees the whole surrounding world, in all directions all at once. That isnt how the mind perceives. At any point of time, the minds attention is limited to some particular object, which then appears perceived. Over a period of time, many things may be perceived, as attention turns to them, one after another. Then, later on, these many things may be conceived together, in a further thought. Or, conversely, the mind may see a single thing and later analyse it into many things, in the course of further thoughts. In either case, it takes time for different things to show up in ones mind. In the present moment, as it is immediately experienced, there is no time for different things to show or to be analysed. What appears is just one object, at the tip of minds attention, which the present object occupies. In each such perception, the object seen is at a focus of attention, narrowed to a single tip. And, in this attention is understood everything that is known about the object: its location, its relationship with other objects, and how it is part of a larger world. Thus, while the object is perceived at the front tip of attention, this narrowed perception is built upon a broader basis of understanding, at the background of experience. For example, suppose a driver notices that his car is sounding a little odd. Many things go into this perception: like how the car sounded before, the various other things that have been happening with the car, what sort of car it is, the uses for which it is needed, the other people who are going to drive it, the drivers previous experiences with cars and machines and mechanics, and so on. All these things are understood at the background of experience, while attention is focused on the sound of the car. The background understanding proFigure 2 vides a subjective basis, upon which the driver listens to the sound. FOCUS OF We have here a mental picture of exATTENTION perience: as rising from an underlying background, so as to focus on a particuOBlar object. Figure 2 shows an illustraJECT tion. What is this subjective basis, at the background of experience? It is evidently the underlying depth of our minds, beneath the apparent surface of limited attention. UNDERSTANDING As attention turns to different objects, they appear one after another at BACKGROUND OF EXPERIENCE the surface of the mind, in a changing

3 stream of limited perceptions. But we know more than this limited and changing surface. As we see an apparent object, we somehow take other things into account, in our understanding of what is seen. So we do not just see things at the front tip of the minds attention. We also understand them, and thus take different things into account, at the background of experience. In effect, we seem to have two different kinds of knowledge in our minds. On the surface, we have a limited and changing perception, through which particular objects appear and disappear. Beneath the changing surface, there is a background knowledge that continues quietly, without distracting attention from the apparent objects which come and go at the surface. This quiet, continuing knowledge enables us to take into account what our minds dont make appear. At first it seems that both these kinds of knowledge are activities of mind. The first is an apparent activity, displaying a successive stream of changing show, rather like the moving pictures on a video screen. The second is a hidden activity, often called unconscious mind. Here, beneath the surface, the mind stores data and processes it; thus acting rather like the inner workings of a computer, behind the information that is displayed. However, neither of these activities is knowledge in itself. Nor are the two together, in any combination. They cannot be experienced without the light of consciousness. In everyones experience, that light is always present, illuminating each of the appearances that come and go in mind. At the tip of minds attention, objects keep appearing and disappearing, in a stream of superficial, passing show. But as appearances thus change, at the surface of the mind, consciousness stays always present, lighting up what comes and goes. As known by the illumination of consciousness, the mind is an objective activity. Through its storage and processing and display of information, it produces the succession of appearances that make up the changing surface of each persons experience. Each appearance is a seeming object, including the entire activity of mind. That too is a object which appears and disappears, as attention turns to it and then turns on to other things. Accordingly, our minds are only instruments of knowledge, like our senses and our bodies. As we experience things subjectively, they are not known by mind, but only through it. Consciousness is not an activity of any mind. Instead, it is the knowing light by which the minds activities are illuminated. It lights the mind from deep within, where there is light alone, unmixed with any changing act. That is at once the inmost centre of experience and its deepest ground as well, beneath all limited appearances. Unmixed light At the changing surface of our minds, whatever comes into appearance must disappear again, as attention turns away from it. But consciousness does not appear and disappear like this. It carries on beneath the surface, at the underlying background of experience, staying always present there. At that background, objects dont appear; for all appearances and disappearances occur above, at the surface of the mind. Beneath the surface, in the depth of our experience, there is an underlying consciousness from where illumination comes. But there, no objects or appearances are

4 seen. Whatevers known is understood, unmixed with any clamouring appearances. Theres nothing else but consciousness, shining always unconfined and undisturbed, all on its own. In short, the background of experience is just consciousness, supporting all the differing appearances that different and changing minds keep superimposing upon it. Thus, consciousness is like a background screen, upon which changing pictures are drawn. It is an ever-present screen, behind our mental picturing. But this screen is not an object that transmits or reflects light. Instead, as consciousness, it is light. In itself, it is just light, unmixed with anything else. In the pictures that we see, this pure light of consciousness seems mixed with changing qualities and objects. Beneath the pictures, consciousness is their unpictured background and their unmixed light as well. These are two ways of looking at it. Life and learning How are the pictures drawn, upon the screen of consciousness? How does its light get mixed, to form the pictures that we see? These questions may be answered through the idea of life. This is yet another way of looking at consciousness. Here consciousness is seen conceived as underlying life. It is the inner source of life, expressed in all our feelings, thoughts and living acts. This conception may be illustrated by adding to our previous diagram, as in figure 3. The addition shows a repeated cycle of expression and reflection, which keeps meFig 3 Learning in the mind

FOCUS OF ATTENTION OBJECT

E R E F L E C T I O N

ACTION X

P R E S S I

FORM

THOUGHT

NAME

FEELING

O N

QUALITY

UNDERSTANDING

C O N S C I O U S N E S S

5 diating between underlying consciousness and objects of perception, in the process of our lives. First, consciousness is expressed: through understanding, feeling, thought and action. But the expression has a limiting effect. It narrows down attention to some limited object, which then appears at the front tip of personal experience. As the object appears, it is perceived, interpreted, judged and understood. This is a reflection back: from the apparent object at the forefront of attention, to underlying consciousness, at the background of experience. There is thus a movement up and down, through five levels that are illustrated in figure 3 (within the broken triangle formed by the three lines). At the uppermost level, objects keep appearing and disappearing, as attention turns to them and turns away from them. At the second level, actions take attention to objects and thus perceive objective forms. At the third level, thoughts direct action and interpret names. At the fourth level, feelings motivate thought and judge qualities. At the fifth level, understanding co-ordinates our faculties and assimilates our changing experiences into continuing knowledge. By repeatedly expressing consciousness and returning back to it, we learn from experience. It is thus that misunderstandings get exposed and clarified, and that our living faculties can be developed and adapted. Through this process of learning, our faculties and personalities get changed. But consciousness continues, as their final, knowing ground. Impartiality At the ground of consciousness, beneath all change, knowing is impartial and impersonal. It is not the partial action of any personal faculty, acting towards one object at the expense of others. Instead, it is a light that shines by virtue of itself. As consciousness illuminates experience, it does not put on any act. Its knowing is just what it always is. Its very being is to know, to shine with knowing light. Thus, beneath appearances, knowing and being are the same. There, our knowing is just what we are. And, that ground of knowing is the same for everyone. Beneath all change and difference, it has no name or form or quality that could distinguish it as differing in different personalities. There is no way in which it can be different in one persons experience, as opposed to another persons experience. Different people act in different ways and see things differently. So actions and appearances can differ. But not the ground of consciousness from which the differences are known. It is our common ground, on which we understand each other and communicate. When consciousness is understood like this, as our undifferentiated ground, there is a change of perspective. Our personalities are then no longer knowing islands of experience. They are just parts of nature, expressing that same ground of consciousness which underlies all happenings experienced anywhere. Consciousness is thus expressed throughout the world, quite naturally and impersonally, in the impersonality of natures ordered happenings. It is not just a poetic, unreasoned metaphor that makes us speak of natures life. Whenever we find the world intelligible, we see order and meaning in it, reflecting back implicitly into a corresponding order and meaning that is expressed from consciousness in our own lives. We are then listening to nature, to what is said by na-

6 tures happenings. Then we are treating nature as alive, as expressing a subjective ground of intelligibility to which we may reflect within ourselves. There is nothing unreasonable or unscientific in this, provided we can recognize that natures life is quite impersonal, expressing an impartially subjective ground that we share in common with it. For nature is complete within itself. It includes all acts and happenings, with all their instruments and capabilities and motivations. So it needs nothing from outside to manifest it. It manifests itself spontaneously, of its own accord, from its own ground of underlying consciousness, which lights each manifest appearance from within. By contrast, our personalities are inherently partial and artificial. They depend on other things, which drive them from outside. Thats because there is in them an inherent partiality which we call ego. This ego is a confusion between doing and knowing. It falsely identifies the partial perceptions of a particular mind and body with the impartial knowing of consciousness. Such mental and physical perceptions are only partial doings, producing the appearances of personal experience. And yet, these partial doings are mistaken to be knowing in themselves. A personal doer, made of partial mind and body, is thus mistakenly identified as knowing self. Then consciousness appears to be a personal possession, belonging to our little personalities. In fact, it is the other way around. Our personalities and all their acts belong to consciousness. They are its limited expressions, just like all else that is experienced in the world. How can this confusion be corrected? How can we correct this false, but deeply ingrained confusion between our personal doings and their impartial ground of knowing, which they can only partially express? Such a correction is of course the aim of spiritual endeavour, which goes about achieving it in many different ways. Some of these ways seem quite opposed to science, but they all share a final aim of freeing knowledge from the partialities of personality. That aim is basic to science as well. Without it, there could be no science.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Awareness - The Mystery of BeingDokument11 SeitenAwareness - The Mystery of BeingDeomatie Sheila RsirjueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Inner Freedom Is Real FreedomDokument2 SeitenInner Freedom Is Real Freedomsiva_ljm410Noch keine Bewertungen

- Bridge The Gap Between Knowing and DoingDokument7 SeitenBridge The Gap Between Knowing and DoingDr.Sree Lakshmi KNoch keine Bewertungen

- How to retrain your brain for positive thinkingDokument2 SeitenHow to retrain your brain for positive thinkingarucard08Noch keine Bewertungen

- Blinded by Fear: Insights From the Pathwork® Guide on How to Face Our FearsVon EverandBlinded by Fear: Insights From the Pathwork® Guide on How to Face Our FearsNoch keine Bewertungen

- You Are God’S Best Idea!: Divine Acceptations and Living the Undeniable LifeVon EverandYou Are God’S Best Idea!: Divine Acceptations and Living the Undeniable LifeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Part Twelve: The Master Key SystemDokument96 SeitenPart Twelve: The Master Key Systemraia.1000Noch keine Bewertungen

- Three Key Aspects of Focusing: Appeared in The Focusing Connection, March 1998Dokument4 SeitenThree Key Aspects of Focusing: Appeared in The Focusing Connection, March 1998Deniz YıldızNoch keine Bewertungen

- First Deserve, Then DesireDokument6 SeitenFirst Deserve, Then DesireRonald Vallone100% (1)

- The InductionDokument11 SeitenThe InductionpnubianpNoch keine Bewertungen

- 43569528-Swami-Vivekananda (Compatibility Mode)Dokument20 Seiten43569528-Swami-Vivekananda (Compatibility Mode)Ravi ChandranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Concentration, Keeping Your Mind On What You Are Reading or Studying, Involves TwoDokument4 SeitenConcentration, Keeping Your Mind On What You Are Reading or Studying, Involves TwoSahan WijerathneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Change Subconscious Beliefs with PSYCH-KDokument4 SeitenChange Subconscious Beliefs with PSYCH-KAdp CiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- WINNERS' HABITS: How to Develop Mindset and Behaviors for Success (2023 Guide for Beginners)Von EverandWINNERS' HABITS: How to Develop Mindset and Behaviors for Success (2023 Guide for Beginners)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Fly: My Life in and out of Religion, Sexuality, and Then SomeVon EverandFly: My Life in and out of Religion, Sexuality, and Then SomeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Pathless Path: Moments with a Real Teacher from Ancient RootsVon EverandThe Pathless Path: Moments with a Real Teacher from Ancient RootsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transform Your Fears: Methods to Channel Your Inner Power and Create a Better LifeVon EverandTransform Your Fears: Methods to Channel Your Inner Power and Create a Better LifeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scientific Studies of Mind, Matter, Spirit and ConsciousnessDokument93 SeitenScientific Studies of Mind, Matter, Spirit and ConsciousnessDevinder LalotraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Master Your Mind, Transfer Your Destiny: Unleash the Power Within to Create the Life You DesireVon EverandMaster Your Mind, Transfer Your Destiny: Unleash the Power Within to Create the Life You DesireNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sub: Research Methodology: Aruna Manharlal Shah Institute of Management Study and Research A M S I M RDokument36 SeitenSub: Research Methodology: Aruna Manharlal Shah Institute of Management Study and Research A M S I M RArun GaderiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- SELF MASTERY THROUGH CONSCIOUS AUTOSUGGESTION (Complete Edition): Thoughts and Precepts, Observations on What Autosuggestion Can Do & Education As It Ought To BeVon EverandSELF MASTERY THROUGH CONSCIOUS AUTOSUGGESTION (Complete Edition): Thoughts and Precepts, Observations on What Autosuggestion Can Do & Education As It Ought To BeBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (9)

- Hypnosis How To Hypnotize Anyone Discover The Secret Hypnotic Techniques and Language Patterns To Hypnotize and Persuade... (Moore, Leonard) (Z-Library)Dokument93 SeitenHypnosis How To Hypnotize Anyone Discover The Secret Hypnotic Techniques and Language Patterns To Hypnotize and Persuade... (Moore, Leonard) (Z-Library)Alwin BennyNoch keine Bewertungen

- In a Perfect World: Man in Relationship with SelfVon EverandIn a Perfect World: Man in Relationship with SelfNoch keine Bewertungen

- 6x9 Allow-Final WithisbnDokument174 Seiten6x9 Allow-Final WithisbnvinodNoch keine Bewertungen

- Broken HeartDokument13 SeitenBroken HeartSunipaSenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Personal Power: Mindfulness Techniques for the Corporate WorldVon EverandPersonal Power: Mindfulness Techniques for the Corporate WorldNoch keine Bewertungen

- May 2012 Totm v1Dokument3 SeitenMay 2012 Totm v1api-114313691Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Keys To Reality - Changing The World (For the Better) through Spiritual Mastery and Prayers for the PlanetVon EverandThe Keys To Reality - Changing The World (For the Better) through Spiritual Mastery and Prayers for the PlanetNoch keine Bewertungen

- You Are God's Gift to the World: The Purpose of Your Life on EarthVon EverandYou Are God's Gift to the World: The Purpose of Your Life on EarthNoch keine Bewertungen

- RealityDokument1 SeiteRealityGoddessLightNoch keine Bewertungen

- Becoming What You Want to See in the World: Expanded Second EditionVon EverandBecoming What You Want to See in the World: Expanded Second EditionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Amen: The Marriage of the Conscious and Subconscious MindVon EverandAmen: The Marriage of the Conscious and Subconscious MindNoch keine Bewertungen

- Truth Is Higher Than Any and Every Thing in the UniverseVon EverandTruth Is Higher Than Any and Every Thing in the UniverseNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Time BubbleDokument14 SeitenThe Time BubbleErniesthoughtsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Awakening the Spiritual Heart: How to Fall in Love with LifeVon EverandAwakening the Spiritual Heart: How to Fall in Love with LifeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Art of Self-Mastery: Empowering Yourself to Create a Fulfilling LifeVon EverandThe Art of Self-Mastery: Empowering Yourself to Create a Fulfilling LifeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Concentration TechniquesDokument6 SeitenConcentration TechniquesRituparnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Awake Final EditedDokument296 SeitenAwake Final EditedFaraz Ahmed100% (1)

- How To Find Your Real Self-Mildred MannDokument14 SeitenHow To Find Your Real Self-Mildred Mannapi-3757433Noch keine Bewertungen

- Morning Mindset ArchiveDokument40 SeitenMorning Mindset ArchiveJohn Doe100% (1)

- The Most Commonly Asked Questions About A Course in MiraclesDokument101 SeitenThe Most Commonly Asked Questions About A Course in MiraclesDougNovato100% (1)

- Letter WitnessDokument1 SeiteLetter WitnessAbhey RanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Herbal Extraction Plant: Profile No.: 162 NIC Code: 01292Dokument14 SeitenHerbal Extraction Plant: Profile No.: 162 NIC Code: 01292Abhey RanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter Vol1-11Dokument11 SeitenChapter Vol1-11Abhey RanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- How I Came to the Maharshi and Found TransformationDokument2 SeitenHow I Came to the Maharshi and Found TransformationAbhey RanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case StudyDokument34 SeitenCase StudyAbhey RanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eca 2014 - Civil Services Mains 2014 Course - 900+ Q&a (200-100 Words)Dokument51 SeitenEca 2014 - Civil Services Mains 2014 Course - 900+ Q&a (200-100 Words)Amit KankarwalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Metanucleus Tech Private Limited: Office: #109, 4Th Floor, Xerion Building, Udyog Vihaar, Phase 4, GurgaonDokument1 SeiteMetanucleus Tech Private Limited: Office: #109, 4Th Floor, Xerion Building, Udyog Vihaar, Phase 4, GurgaonAbhey RanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- N PDFDokument771 SeitenN PDFAbhey RanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- GLA ClassDokument52 SeitenGLA ClassAbhey RanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Economic Survey CoverDokument1 SeiteEconomic Survey CoverAbhey RanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Creative Writing Summer School 2015Dokument2 SeitenCreative Writing Summer School 2015Abhey RanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2003 Deepam RamanaDokument69 Seiten2003 Deepam RamanaAbhey RanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital PunishmentDokument44 SeitenCapital PunishmentAbhey RanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- World Health Organization: Energy Access Report BriefDokument1 SeiteWorld Health Organization: Energy Access Report BriefTrees, Water and PeopleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Common FaithDokument5 SeitenCommon FaithAbhey RanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guiding PresenseDokument33 SeitenGuiding PresenseAbhey RanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A2 Religious LanguageDokument6 SeitenA2 Religious LanguageAbhey RanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Tribute from France: Meditation, Action and the Path to Self-RealizationDokument3 SeitenA Tribute from France: Meditation, Action and the Path to Self-RealizationAbhey RanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Climate Profile of ChennaiDokument129 SeitenClimate Profile of ChennaiAparna KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Buddha And Ramana - Guiding Men To Self-RealizationDokument3 SeitenBuddha And Ramana - Guiding Men To Self-RealizationAbhey RanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Peom PrintDokument1 SeitePeom PrintAbhey RanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sri Ramana Stuti- PanchakamDokument7 SeitenSri Ramana Stuti- PanchakamAbhey RanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- MOEF Statement On Activities and Achievements in 2013Dokument89 SeitenMOEF Statement On Activities and Achievements in 2013Abhey RanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sri Ramana Stuti- PanchakamDokument7 SeitenSri Ramana Stuti- PanchakamAbhey RanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Namaste Sri RamananDokument2 SeitenNamaste Sri RamananAbhey RanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1985 Vol 22 NoiDokument73 Seiten1985 Vol 22 NoiAbhey RanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sans ListDokument1 SeiteSans ListAbhey RanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Platform For Action Report On Indian WomenDokument100 SeitenPlatform For Action Report On Indian WomenAbhey RanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sans ListDokument1 SeiteSans ListAbhey RanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Peom PrintDokument1 SeitePeom PrintAbhey RanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Individual Education Plan: Sample 3Dokument6 SeitenIndividual Education Plan: Sample 3fadhilautamiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ict Learning TheoryDokument3 SeitenIct Learning Theoryapi-312023795100% (1)

- MA English Semester System 2012Dokument22 SeitenMA English Semester System 2012Snobra Rizwan100% (1)

- Listening SkillsDokument9 SeitenListening SkillsMohd Shabir100% (1)

- 4176Dokument3 Seiten4176Poongodi ManoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Systematic Review SampleDokument5 SeitenSystematic Review SampleRubeenyKrishnaMoorthyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sabelli, Ferreyra, Cappelletti, GiovanniniDokument1 SeiteSabelli, Ferreyra, Cappelletti, GiovanniniMarianela GiovanniniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter Bylaws of The Classical Academy High School Chapter of The National Honor Society Adopted: On This Day, 6th of December in The Year 2016Dokument7 SeitenChapter Bylaws of The Classical Academy High School Chapter of The National Honor Society Adopted: On This Day, 6th of December in The Year 2016api-337440242Noch keine Bewertungen

- Web Application For Automatic Time Table Generation: AbstractDokument7 SeitenWeb Application For Automatic Time Table Generation: AbstractsairamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 6.5 Strategic Marketing Level 6 15 Credits: Sample AssignmentDokument2 SeitenUnit 6.5 Strategic Marketing Level 6 15 Credits: Sample AssignmentMozammel HoqueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mandate Letter: British Columbia Ministry of EducationDokument3 SeitenMandate Letter: British Columbia Ministry of EducationBC New DemocratsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Department of Education: Schools Division of Ozamiz CityDokument6 SeitenDepartment of Education: Schools Division of Ozamiz CityClaire Padilla MontemayorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Verbal Abuse-Irony RaftDokument8 SeitenVerbal Abuse-Irony Raftapi-282043501Noch keine Bewertungen

- Talk2Me Video - : Before WatchingDokument1 SeiteTalk2Me Video - : Before WatchingRocio Chus PalavecinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Instructional Planning for Triangle CongruenceDokument4 SeitenInstructional Planning for Triangle CongruencePablo JimeneaNoch keine Bewertungen

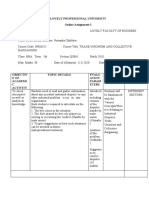

- LOVELY PROFESSIONAL UNIVERSITY Online Assignment on Trade UnionismDokument3 SeitenLOVELY PROFESSIONAL UNIVERSITY Online Assignment on Trade UnionismSan DeepNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dharma Talk Given by Jordan KramerDokument3 SeitenDharma Talk Given by Jordan KramerjordanmettaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Osias Educational Foundation School Year 2020-2021 Course SyllabusDokument2 SeitenOsias Educational Foundation School Year 2020-2021 Course SyllabusJonalyn ObinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- RhetoricDokument22 SeitenRhetoricCarlos ArenasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Syllabus - Hoa Iii - Sy 2017-2018Dokument6 SeitenSyllabus - Hoa Iii - Sy 2017-2018smmNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Impact of Technology On EducationDokument8 SeitenThe Impact of Technology On EducationAnalyn LaridaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CBC Emergency Medical Services NC IIDokument159 SeitenCBC Emergency Medical Services NC IIPrecious Ann Gonzales Reyes100% (2)

- Detailed Lesson PlanDokument9 SeitenDetailed Lesson PlanSairin Ahial100% (1)

- VALIDATION AND INTEGRATION OF THE NCBTS-BASED TOS FOR LET MAPEHDokument30 SeitenVALIDATION AND INTEGRATION OF THE NCBTS-BASED TOS FOR LET MAPEHhungryniceties100% (1)

- Hand-0ut 1 Inres PrelimsDokument7 SeitenHand-0ut 1 Inres PrelimsJustin LimboNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strategies To Teach SpeakingDokument14 SeitenStrategies To Teach SpeakingDías Académicos Sharing SessionsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Edu 3410 Poem Lesson PlanDokument3 SeitenEdu 3410 Poem Lesson Planapi-338813442Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson Plan English 9 MayDokument2 SeitenLesson Plan English 9 MayPerakash KartykesonNoch keine Bewertungen

- North V. South The Impact of Orientation PDFDokument6 SeitenNorth V. South The Impact of Orientation PDFMohammad Art123Noch keine Bewertungen

- RWS Week-1Dokument14 SeitenRWS Week-1LOURENE MAY GALGONoch keine Bewertungen