Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Chap 7

Hochgeladen von

Sunil ChaudharyOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Chap 7

Hochgeladen von

Sunil ChaudharyCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

U N I T-V

FACTOR PRICE DETERMINATION

FACTOR PRICE DETERMINATION

123

CHAPTER

FACTOR PRICE DETERMINATION

7.1 Factor Demand

7.2 Total Factor Demand, Factor Supply and Equilibrium

7.3 Trade Unions

In Chapter 2 to Chapter 6, we examined the product markets: which good or service will be produced, and if so, how much and what its price will be. In other words we dealt with the central problem of what facing an economy. Households are demanders and firms are suppliers in product markets. In this chapter we examine factor or input markets, e.g., different types of labour or skill, capital (i.e. machinery and equipment), land etc. In factor markets, firms are demanders and households are suppliers. There are similarities and dissimilarities between product and factor markets. Dissimilarities arise because the demanders and suppliers in a factor market are opposite of who they are in a product market. The issues are different also. Instead of the economys central problem of what, the factor market analysis sheds light on the for whom problem. For example, consider the labour market. The price of labour service is the wage rate. We will learn how the wages to different types of labour are determined in a market economy. In general, earnings to different individuals in the form of wage income or income from land etc. determine income distribution in an economy. Income distribution, in turn, determines differences

124

INTRODUCTORY MICROECONOMICS

in the purchasing power over goods and services among individuals or households. This is how the factor market implications are linked to central problem of for whom. The similarity between factor and product markets lies in that there is a demand side and there is a supply side of a factor. The equality between demand and supply of a factor determines the respective factor price. 7.1 FACTOR DEMAND 7.1.1 A Firms Problem At a given point of time, a firm faces different prices for different factors. For instance, think of a transport and storage company. It employs workers, rents warehouse space for storage etc. The prevailing hourly wage rate may be Rs. 15. Warehouse facility may be available at the rate of Rs. 50 per day per cubic metre of space. The question is, given factor prices, how much of different factors a profit-maximising firm should hire? On one hand, hiring more of factors will generate more output, which will generate more revenues (as long as the marginal revenue is positive). On the other hand, hiring more factors will cost more. 7.1.2 One Variable Factor To begin with, suppose that the employment levels of all factors, except one, are fixed, i.e., there is only one variable input and the rest are fixed. Let this variable factor be called labour, measured in hours of work. (If all workers are supposed to work a

given number of hours per day, then we can measure labour as the number of workers hired.) In other words, we are not differentiating between different types of workers at the moment. The question is, how many labour hours (denoted by L) a firm should employ? The total cost of fixed factors is fixed by definition. The total cost of the variable factor (labour in our example) is easy to compute. Suppose that the wage rate is Rs. 20 per hour. If the firm hires 4 hours of labour, the total cost of labour is Rs. 20 4 = Rs. 80. If 7 hours of labour are hired, the total cost of labour or the total wage bill is Rs. 20 7 = Rs. 140, and so on. The way a firms total revenue changes with employment of a factor contains two steps: (a) how changes in the employment of the factor affect output and (b) how changes in output affect total revenue. Realise that we have already studied (a) in Chapter 3. We also have analysed (b) for a competitive firm in Chapter 4 and for a monopoly firm in Chapter 6. What we need to do then is to combine what we have already learnt. For simplicity, let us assume throughout this chapter that the firm under consideration is a perfectly competitive firm. From Chapter 3, recall in particular the definitions of Total Physical Product (TPP) and the Marginal Physical Product (MPP). The former refers to different levels of total output at different levels of employment

FACTOR PRICE DETERMINATION

125

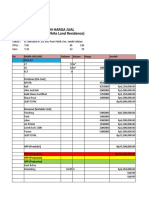

of a factor, when the employment of other factors is unchanged. The latter is the increase in total output per unit increase in the employment of a factor when the employment of all other factors is held constant. From Chapter 3, we also know the shapes of the TPP and MPP curves. In particular, the inverse U-shape of the MPP curve follows from the law of diminishing returns. We need two more concepts before we are able to answer in principle the question of how much of a factor a profit-maximising competitive firm will employ. The first is the Total Value Product (TVP), defined as P TPP, where P is the product price. This is indeed same as total revenue. The Table 7.1 Labour Hours (L) 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

second one is the Value of the Marginal Product (VMP), defined as P MPP. Equivalently, VMP is equal to the increase in TVP or total revenues per unit increase in the employment of the factor. It is because an extra unit employed of a factor generates extra output equal to MPP, which will fetch extra revenues equal to the value of this extra output. Consider the TPP schedule and the MPP schedule, as given in Tables 3.2 and 3.3 in Chapter 3. In order to calculate the TVP and the VMP, we need to know the product price. Suppose that P = Rs. 2. Table 7.1 gives the TPP schedule, the MPP schedule as well as the associated TVP and VMP schedules.

TPP, MPP, TVP and VMP Schedules MPP 10 12 11 10 8 5 0 8 12 Product Price = Rs. 2 TVP = P.TPP (Rs.) 0 20 44 66 86 102 112 112 96 72 VMP = P.MPP (Rs.) 20 24 22 20 16 10 0 16 24

TPP 0 10 22 33 43 51 56 56 48 36

126

INTRODUCTORY MICROECONOMICS

Particularly relevant for us will be the VMP schedule and its properties. A. It is proportional to the MPP schedule as it is obtained by multiplying the MPP schedule by price, which is constant. This implies that the law of diminishing returns, which governs the nature of the MPP schedule, also determines the nature of the VMP schedule. It initially increases with factor employment and then diminishes. B. TVP of a particular level of factor employment is the sum of VMPs up to that level of employment. For instance, at L = 3, TVP = 66. This is equal to the sum of VMPs at L = 1 (20), at L =2 (24) and at L = 3 (22). Property A implies that the VMP curve, the graphical representation of a VMP schedule, will be inverse Ushaped, just as the MPP curve. This is illustrated in fig. 7.1(a). Property B implies that, if we draw a smooth VMP curve, the area under it will be equal to the TVP (i.e. the total revenue). A general, smooth VMP curve is shown in fig. 7.1(b). For instance, at L = L1, the TVP is equal to the area 0ABL1. So far we have analysed concepts that help in understanding how an increase in the employment of a factor af fects the total revenues of a competitive firm. Now we discuss how it affects its costs. Suppose that the factor L costs W per unit, i.e., the hourly wage rate is Rs. W. Fig. 7.2 draws the Factor Price Line or the wage line in this case. It is a horizontal line since the wage rate is unaffected by how many labour hours our

(a)

(b) Fig. 7.1 The VMP Curve

competitive firm by definition, a small firm hires in the labour market. The point to note for us is that the area under the factor price line is the total factor cost or payment to the factor. If, for instance, the firm hires L1 labour hours, its total wage bill is the area 0WCL1.

Fig. 7.2 Factor Price Line

FACTOR PRICE DETERMINATION

127

We are now ready to derive the principle that governs how many labour hours a profit-maximising firm should hire. Turn to fig. 7.3, which combines figs. 7.1(b) and 7.2. Let the factor price facing the firm (wage rate) be W0. The answer is that the firm should hire up to that level, where the factor price line intersects the VMP curve, i.e. it should hire L0 labour hours. In other words, the general principle of hiring a factor (or profitmaximisation with respect to a particular factor) is (A) VMP of a Factor = Its Price.

Fig. 7.3 Factor Employment Decision

This condition is perfectly parallel to the profit-maximising condition for a competitive firm, that is P = MC. Indeed the two conditions are two sides of the same coin. The rationale behind condition (A) is also parallel to that behind P = MC. At L = L0 , TVP or total revenue is equal to the area 0ACL0. The total factor cost is equal to the area

1

0W0 CL0. Thus the gross profit, which is the difference between TVP and total factor cost, is equal to the area W0 AC.1 Now consider any employment level less (such as LA) or more (such as LB) than L0. We can compute that the profit is less than W0 AC. For instance, at L = LA, it is equal to W0 AFD, which is equal to W0 AC CDF. At L = LB, it is equal to W0 AC CEG. This proves that profit is maximised at L = L0. The law of diminishing returns is the key. Starting from where the VMP of a factor is equal to its price and the MPP is diminishing, if the firm hires one extra unit of the factor, the VMP will be less than the factor price. This is same as saying that the additional revenue generated (equal to VMP) is less than the additional cost incurred (equal to the factor price). This implies less profit than before. Similarly, if the firm hires one less unit than where VMP is equal to the factor price, the VMP will be higher than the factor price. As a result, the revenue sacrificed (equal to VMP) by hiring one unit less will be more than the savings on the total factor cost (equal to the factor price). Thus profit will be less. In summary, under diminishing returns, any deviation from the principle (A) will only generate less profit. This proves why profit is maximised when condition (A) is met.

The adjective gross is attached, since fixed costs are not deducted. By definition, profit = gross profit fixed cost. However, since the fixed costs are given, gross profit is maximised where profit is maximised and vice versa.

128

INTRODUCTORY MICROECONOMICS

Factor Demand Curve Note from the preceding discussion that a firm always chooses a point on the VMP curve, and moreover, never at a point where diminishing returns do not hold. This means that the downward portion of the VMP curve is the firms demand curve for the factor.2 It also means that a firms demand curve for a factor is downward sloping. Next we examine the determinants or the sources of shift of the factor demand curve. 7.1.3 Factor Demand Curve Shifts Since the factor demand curve is a part of the VMP curve, anything that shifts the VMP curve shifts the factor demand curve. We consider the following sources of change. A Change in Product Price By definition, VMP = P.MPP. Hence an increase in the product price, P, increases the VMP at any given level of factor employment. As a consequence, the factor demand curve shifts to the right (or up). This is illustrated in fig. 7.4. In general then, we can say that an increase (a decrease) in the product price shifts the factor demand curve to the right (left). From this result, we can see a link between product and factor markets. For instance, consider the industry of a particular handicraft. On the demand side, the product is sold in

2

Fig. 7.4 Product Price Increase and Factor Demand

India and abroad. On the supply side, there are artisans, who, with the help of raw materials and equipment, make the handicraft. Suppose that in an international exhibition this handicraft attracts a lot of attention. Many people and organisations around the world come to know about it and they like it. Consequently there is an increase in demand for this handicraft. From the demand-supply analysis in Chapter 5 we know the effect: the price of this handicraft increases. Now consider the (factor) market for artisans. The increase in the price of the handicraft will shift their VMP curve and hence the demand curve for artisans to the right. The general point here is that factor demand is, in a sense, derived from product demand. This is why, factor demand is said to be a derived demand.

This is parallel to the supply curve of a firm being same as the upward sloping portion of the marginal cost curve.

FACTOR PRICE DETERMINATION

129

(a) Technological Change increasing the

MPP of a Factor

such that the MPP of a factor increases, then the demand curve for that factor shifts to the right. Fig. 7.5(a) shows this effect. Otherwise, if the MPP of a factor decreases due to a technological change, then its demand curve shifts to the left. Fig. 7.5(b) illustrates this. For example, it is widely believed by economists that, in recent two/three decades, the whole world economy has experienced technological progress that has increased the MPP of skilled labour. Whether it has increased the MPP of unskilled labour is not clear.3 7.1.3 Marginal Productivity Theory of Distribution So far we have assumed that the firm employs only one variable factor of production. In reality, firms employ many, e.g., different types of labour, raw materials, power, various kinds of machines, land etc. What are the (profit maximising) principles that govern the simultaneous demand/ employment of more than one factor? They are simply the extensions of the condition (A). If, for example, there are two factors, say X and Y, their respective prices are WX and WY, and their respective marginal products are MPPX and MPPY, the profit-maximising principles are: (A') VMPX = P.MPPX = WX , VMPY = P.MPPY = WY.

(b) Technological Change lowering the MPP

of a Factor

Fig. 7.5

Technological Change and Factor Demand

Technological Change A technological change can alter the MPP of a factor and thereby its demand curve, even when the product price is unchanged. If it is

3

Another possible source of a shift in the factor demand curve, which we have not discussed and which is something to be done in a higher course in microeconomics, is the change in the employment of other factors.

130

INTRODUCTORY MICROECONOMICS

That is, profit is maximised when the VMP of each factor is equal to its price. Note that even when there is more than one variable factor, the definition of MPP remains valid. Recall, from Chapter 1, the central problem of for whom facing an economy, which concerns who earns how much. The conditions (A') imply a theory of this, that is, each factor ear ns the value of its marginal physical product. It is called the marginal productivity theory of distribution. This theory implies, for example, that skilled workers normally earn more than unskilled workers, because the (marginal) productivity of skilled workers is greater than that of unskilled workers. To see this more exactly, suppose that factor X is skilled labour, factor Y is unskilled labour, WX is the skilledlabour wage and WY is the unskilledlabour wage rate. Both work in the same sector, and, let P be the price of the good produced in that sector. Then from (A),

7.2

TOTAL FACTOR DEMAND, FACTOR SUPPLY AND EQUILIBRIUM

WX WY

P .MPPX P .MPPY

MPPX . MPPY

Hence, if MPPX > MPPY, then WX >WY . That is, skilled labour earns more than unskilled labour.

4

In principle, factor prices should be determined by forces of demand and supply both, not just by demand forces that we have emphasised so far. However, when we do take into account the supply side, the marginal productivity theory does hold, with appropriate interpretation. In order to see this and analyse factor market equilibrium in general, let us return to the one-factor case. We have derived a single firms demand for a factor. There are many fir ms in a per fectly competitive industry. So, if we sum up the demand for a factor across various firms, we get the total industry demand curve for that factor.4 However, some factors are used in many industries and in that case, the total demand curve for a factor is the horizontal summation of individual (firm) demand curves for that factor in various industries combined. In Fig. 7.6(a) and (b), the total demand for a factor is shown as the line DD. 5 We now turn to the supply side. Consider, for example, teaching service as a factor of production (in producing education). If the salaries of school teachers increase, more people than before will be willing to choose school

The derivation of total demand for a factor is more complicated than the derivation of market demand curve for a commodity. This complication arises due to a change in the price of the commodity when all firms increase or decrease their outputs together. To simplify the discussion, the price of the commodity is implicitly kept constant during this summing up. How DD is derived is parallel to how the product market demand curve is derived from individual demand curves.

FACTOR PRICE DETERMINATION

131

teaching as a career. Hence the supply curve of this factor service is upward sloping. This is, however, true in the long run. In the short run, like over a few months or over a year, the supply of school teachers in a particular region will be given, because teachers education, training and certification etc. take years. This is true for almost any type of (relatively high) skill. The short run and long run factor supply curves, denoted by SS, of a particular skill are shown in panel (a) and panel (b) of fig. 7.6 respectively. The intersection of demand and supply curves defines equilibrium in the factor market similar to what happens in a product market. In both panels, E denotes the market equilibrium point. The equilibrium wage is denoted by W0, and N0 denotes the equilibrium amount of the particular skilled labour that is hired. Besides different types of labour, a firm hires land, capital etc. These are examples of non-human factors of production. Consider for instance the supply of land. Here land does not just mean a piece of land per se but includes room, building floors etc. In the short run the land supply is given. In the long run it is likely to change. The earning of land is the rent per unit of space. Higher the rent, more land or space will be supplied by landowners.6 Hence the long-run supply curve of land is upward sloping also.

6 7

(a) Short Run

(b) Long Run Fig. 7.6 Demand, Supply and Market Equilibrium of a Particular Skill

Thus the land market equilibrium is similar to that of a particular skill. Fig. 7.6 applies except that rent substitutes the wage rate and land substitutes labour. A point to note here is that, if we interpret land narrowly in terms of area on ground, the supply of land to a particular industry is upward sloping (in the long run), but land supply to the entire economy is given.7

In the present context this is the price of land in terms of its service as a factor of production. It is different from price of land as an asset. There are exceptions. Countries like Japan and Hong Kong have claimed land from sea.

132

INTRODUCTORY MICROECONOMICS

Capital is also a factor of production. The term capital in economics means different things in different contexts. Here it means plants, equipment, machinery etc. It is similar to land in that it is non-human. We say that capital earns rental. If you own an Ambassador car and use it for taxi business, then the hourly or daily rate you charge is an example of capital earning rental. It is dissimilar to land in that the total capital stock in an economy is reproducible, i.e. it can be increased continuously over time, whereas the total land space is non-reproducible. In any event, fig. 7.6 applies to the market for a particular type of capital. There are two general implications of our factor demand-supply analysis. A. An increase in demand for a factor tends to increase its price (by shifting out its demand curve) and an increase in the supply of a factor tends to lower its price (by shifting out its supply curve). By now this conclusion must be something very evident to you. It can be applied to various sources of shifts and their effect on factor price. For instance, if there is an increase in the demand for a commodity, the production of which requires a specific skill (e.g. computer skills), the wage of this skill (e.g. of computer engineers) will increase. A technological change that improves the MPP of a factor will enhance its reward. B. Whichever factor is under consideration, at the equilibrium

point, from the demand side, the factor reward is equal to the value of its marginal physical product. Thus the marginal productivity theory holds when the marginal physical product is evaluated at the equilibrium quantity of the factor service that is in use. 7.3 TRADE UNIONS

The demand-supply analysis above refers to how the price/market mechanism works in factor markets. This is parallel to our demandsupply analysis for commodities in Chapter 5. In that chapter we also saw that the government sometimes directly intervenes in a market and fixes the price of a product in the form of control price and support price. In the factor market, there is also an important example where a factor price is not determined by the market. You might have heard of workers organisation in various sectors of the economy called trade unions or labour unions. These unions voice grievances of workers in a collective way. Sometimes they organise strikes and boycott work for days and weeks. Very often they also try to bargain for higher wages than the employers are willing to offer. Sometimes they succeed in negotiating a wage rate, which is higher than what the equilibrium wage rate would have been in the labour market. What effect does this wage-fixing by trade unions have on the labour market? Turn to fig. 7.7, where Ls denote the total number of workers. This is the supply curve of labour. The

FACTOR PRICE DETERMINATION

133

demand curve for labour is denoted by LD. If there were no trade unions, the intersection of the labour supply and labour demand curves would have determined the market wage rate. In the diagram, W0 would have been market wage. Now suppose that the trade union fixes the wage at W1, which is higher than W0. As a result, the firms will demand less labour, which is indicated at the point D1 on the labour demand curve, or equivalently, at the point L1 on the horizontal axis. What we see now is that there is unemployment of labour; L 1 L s measures the number of workers who are unemployed.

Fig. 7.7 Trade Unions and Unemployment

Thus, unemployment sometimes may be caused by the presence of trade unions.

SUMMARY

l l l l l l l l

A factor service is demanded by firms and supplied by households. Factor price is determined by forces of demand and supply of a factor. For a competitive firm, the VMP curve of a factor is generally inverse U-shaped. This is because of the law of diminishing returns. For a competitive firm, TVP of a factor is equal to the area under its VMP curve. The total factor cost or payment to a factor is the area under the factor price line. For a competitive firm, profit maximisation occurs when each factor is paid its VMP. The demand curve for a factor is essentially the downward sloping portion of its VMP curve. An increase in the product price shifts out the demand curve of a factor. In this sense, the demand for a factor is derived demand.

134 l l l l l l l l

INTRODUCTORY MICROECONOMICS

The MPP of a factor and hence its demand curve can shift because of technological changes. Marginal productivity theory implies that different factors are paid differently because of differences in their VMPs. Skilled labour is paid more than unskilled labour because the marginal product of former is higher than that of the latter. The total demand curve for a factor is the horizontal summation of individual (firm) demand curves for that factor. The supply curve of a factor is upward sloping in the long run, but it may be vertical in the short run. Capital, as a factor of production, is different from land in the sense that, unlike land, it is typically reproducible. An increase in the demand for a factor tends to increase its price, while an increase in the supply of a factor tends to lower its price. When a labour union fixes a wage above the market-clearing wage, unemployment results in the labour market. It is because, at a higher wage rate, firms employ less labour, while the supply of labour by workers may increase or remain unchanged.

EXERCISES

Section I

7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 7.9 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 Who are the demanders in the factor markets? Who are the suppliers in the factor markets? To which central problem does the problem of factor pricing relate to? How are TVP and TPP of a factor related? How are VMP and MPP of a factor related? What is the difference between MPP and VMP of a factor? How is the TVP of a factor derived from its VMP curve? What happens to TVP of a factor when its VMP is positive? What happens to TVP of a factor when its VMP is negative? How is the total payment to a factor derived from the factor price line? What is the relationship between the VMP curve and the factor demand curve? Name two factors responsible for a shift in the factor demand curve. What is the relationship between the wage rate that a labour union typically fixes and the equilibrium wage rate?

FACTOR PRICE DETERMINATION

135

Section II

7.14 The TVP at the employment level L = 4 is 50 units. That at L = 5 is 65 units. The price of the product is Rs. 3. What is the MPP at L = 5? The product price is Rs. 5. The TPP schedule of a factor is given in the following table. Derive its VMP schedule. Employment of a Factor 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 7.16 TPP (units) 0 8 20 32 42 50 56 60 62

7.15

7.17

7.18 7.19 7.20 7.21 7.22

The total payment to a factor is Rs. 12,000. The price of the factor is Rs. 40. How many units of that factor are being employed? Suppose that the product price is Rs. 10 and a factor is paid Rs. 70 per unit. The law of diminishing returns holds. At some level of employment, MPP = 5. Show that, at this level of employment, profit is not being maximised. Should the firm increase or decrease employment in order to increase its profits? Explain why a factor demand is called derived demand. What does the marginal productivity theory of distribution say about the earnings of different factors? Explain why skilled workers earn more than unskilled workers. How does an increase in the supply of a factor affect its earning (price)? Unfortunately an earthquake hits a town and destroys many residential flats, which were used for renting. All other things

136

INTRODUCTORY MICROECONOMICS

7.23

remaining unchanged, will this affect the demand curve or the supply curve of residential flats for rent and how? How will it affect the rental rate per month? Suppose that technological advance takes place in such a way that the MPP of skilled labour increases. How will it affect the wage of skilled labour? Further suppose that the technology advance lowers the MPP of unskilled labour. How will it affect the wage of unskilled labour?

Section III

7.24 7.25 Explain how profit is maximised when the VMP of a factor is equal to its price. Explain why, under perfect competition, the VMP curve for an input is considered its demand curve.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- A World of Regions-Module 2Dokument11 SeitenA World of Regions-Module 2Lara Tessa VinluanNoch keine Bewertungen

- PAMB Medical Revision-35376814 PDFDokument9 SeitenPAMB Medical Revision-35376814 PDFSoon SoonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Modular Harga Jual WLR2Dokument25 SeitenModular Harga Jual WLR2Next LevelManagementNoch keine Bewertungen

- Benefits & Risks of The Resale Price MethodDokument2 SeitenBenefits & Risks of The Resale Price MethodLJBernardoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Appendix C Appendix DDokument4 SeitenAppendix C Appendix DKtNoch keine Bewertungen

- Agri CHAPTER 3 and 4Dokument22 SeitenAgri CHAPTER 3 and 4Girma UniqeNoch keine Bewertungen

- ACCOUNTING 3B Homework 3Dokument3 SeitenACCOUNTING 3B Homework 3Jasmin Escaño100% (1)

- AralPan8 - Q4 - Wk8 - ANG UNITED NATIONS AT IBA PANG PANDAIGDIGANG ORGANISASYON, PANGKAT AT ALYANSA - WINNIE S. BALUDEN - CONNIE TULAN-1Dokument14 SeitenAralPan8 - Q4 - Wk8 - ANG UNITED NATIONS AT IBA PANG PANDAIGDIGANG ORGANISASYON, PANGKAT AT ALYANSA - WINNIE S. BALUDEN - CONNIE TULAN-1Jaiz Cadang100% (1)

- Allocation and Apportionment and Job and Batch Costing Worked Example Question 2Dokument2 SeitenAllocation and Apportionment and Job and Batch Costing Worked Example Question 2Roshan RamkhalawonNoch keine Bewertungen

- I. Title: "A Study On The Feasibility of Establishing A Dairy Goat Farm in Barangay Meysulao, Calumpit, Bulacan"Dokument31 SeitenI. Title: "A Study On The Feasibility of Establishing A Dairy Goat Farm in Barangay Meysulao, Calumpit, Bulacan"Joama Febrille DinNoch keine Bewertungen

- MMTC Student's Manual 2021Dokument105 SeitenMMTC Student's Manual 2021Priyanshu Gupta100% (1)

- VinfastDokument8 SeitenVinfastThị Ninh DươngNoch keine Bewertungen

- Entrepreneurship DevelopmentDokument94 SeitenEntrepreneurship Developmentashish9dubey-16Noch keine Bewertungen

- VCC LitepaperDokument10 SeitenVCC LitepaperjuvriNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 Analysis of FRS 138 Intangible AssetsDokument12 Seiten1 Analysis of FRS 138 Intangible AssetsWilber Loh100% (1)

- The Emergence of Angel Investment Networks in Southeast Asia Report I A Good Practice Guide To Effective Angel InvestingDokument58 SeitenThe Emergence of Angel Investment Networks in Southeast Asia Report I A Good Practice Guide To Effective Angel InvestingRick WongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hancock9e Testbank ch07Dokument16 SeitenHancock9e Testbank ch07杨子偏Noch keine Bewertungen

- Arts 484-490 CO Study GuideDokument5 SeitenArts 484-490 CO Study GuideVikki AmorioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Characteristics and Risks of Standardized OptionsDokument95 SeitenCharacteristics and Risks of Standardized OptionsBálint GrNoch keine Bewertungen

- SBMC Blank v2 2 PDFDokument1 SeiteSBMC Blank v2 2 PDFSusan BvochoraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Project Finance SCDL Paper Solved Exam Paper - 9Dokument4 SeitenProject Finance SCDL Paper Solved Exam Paper - 9Deepak SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Accounting For Merchandising Operations: Pertemuan 7Dokument16 SeitenAccounting For Merchandising Operations: Pertemuan 7Herry ArsevenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 2Dokument26 SeitenModule 2golu tripathiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Timken Case Study: The Merits of An Acquisition of Rulmenti Grei and The Risks For TimkenDokument7 SeitenTimken Case Study: The Merits of An Acquisition of Rulmenti Grei and The Risks For TimkenHa DoanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hive-Off Strategies Slump Sale PGDMDokument18 SeitenHive-Off Strategies Slump Sale PGDMgagan3211100% (1)

- Cheatue - Case 1Dokument5 SeitenCheatue - Case 1Steven XieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Date Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing BalanceDokument7 SeitenDate Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing BalancePDRK BABIUNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corporate Governance and Bank Performance: Evidence From ZimbabweDokument32 SeitenCorporate Governance and Bank Performance: Evidence From ZimbabweMichael NyamutambweNoch keine Bewertungen

- IFRS 17 Insurance Contracts Why Annual Cohorts 1588124015Dokument6 SeitenIFRS 17 Insurance Contracts Why Annual Cohorts 1588124015Grace MoraesNoch keine Bewertungen

- CB5E45903BDokument1 SeiteCB5E45903Bkrish tcrNoch keine Bewertungen