Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

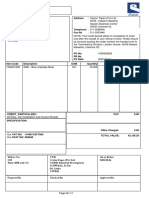

KMPG Mpotion Re-Accounting

Hochgeladen von

ny1davidOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

KMPG Mpotion Re-Accounting

Hochgeladen von

ny1davidCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Case 1:04-cv-01639-RJL Document 994 Filed 01/06/12 Page 1 of 26

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

MDL No. 1668 In re Fannie Mae Securities Litigation

REDACTED

Civil Action No. 1:04-cv-01639 (RJL)

KPMG LLPS REPLY MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF ITS MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT

Case 1:04-cv-01639-RJL Document 994 Filed 01/06/12 Page 2 of 26

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................1 ARGUMENT ...................................................................................................................................4 I. Plaintiffs Fail To Put Forward Evidence That KPMG Acted Fraudulently.............4 A. B. The Undisputed Evidence Is That KPMG Believed Its Audit Opinions .......................................................................................................4 Plaintiffs Do Not Show Fraud In KPMGs Accounting And Auditing Judgments .....................................................................................6 1. FAS 133 ..................................................................................................6 2. FAS 91 and FAS 115 ..............................................................................9 3. Reviewing Fannie Maes Accounting Policies Prior to Implementation Was Not Fraud .....................................................11 C. D. E. F. II. The Fees KPMG Received Do Not Show Fraudulent Intent .....................12 Plaintiffs Contradictory Arguments About Earnings Manipulation Prove Nothing ............................................................................................13 Plaintiffs Reliance on the Restatement Is Equally Unavailing .................15 Criticism of Other KPMG Audits Is Not Evidence of Scienter Here ........18

Plaintiffs Do Not Meaningfully Oppose KPMGs Motion for Summary Judgment on Loss Causation and Damages ...........................................................18

CONCLUSION ..............................................................................................................................20

Case 1:04-cv-01639-RJL Document 994 Filed 01/06/12 Page 3 of 26

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Page

Cases AUSA Life Ins. Co. v. Ernst & Young, 206 F.3d 202 (2d Cir. 2000)........................................................................................................ 4 Brooke Grp. Ltd. v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp., 509 U.S. 209 (1993) .................................................................................................................. 14 Coward v. ADT Sec. Sys. Inc., 194 F.3d 155 (D.C. Cir. 1999) .................................................................................................... 2 *Dronsejko v. Grant Thornton, 632 F.3d 658 (10th Cir. 2011) .................................................................................................. 15 DSAM Global Value Fund v. Altris Software, Inc., 288 F.3d 385 (9th Cir. 2002) ...................................................................................................... 2 *Fait v. Regions Financial Corp., 655 F.3d 105 (2d Cir. 2011)....................................................................................................... 4 *Fidel v. Farley, 392 F.3d 220 (6th Cir. 2004) .............................................................................................. 12, 15 Fine v. Am. Solar King Corp., 919 F.2d 290 (5th Cir. 1990) ...................................................................................................... 5 Hunter v. Rice, 480 F. Supp. 2d 125 (D.D.C. 2007) ............................................................................................ 4 In re Acceptance Ins. Cos. Sec. Litig., 423 F.3d 899 (8th Cir. 2005) ...................................................................................................... 3 In re Ceridian Corp. Sec. Litig., 542 F.3d 240 (8th Cir. 2008) .................................................................................................... 16 *In re Fannie Mae Sec. Litig., 503 F. Supp. 2d 25 (D.D.C. 2007) ............................................................................................ 15 *In re IKON Office Solutions, Inc., 277 F.3d 658 (3d Cir. 2002)........................................................................................................ 2 In re Lehman Bros. Sec. & ERISA Litig., Nos. 09 MD 2017, 08 Civ. 5523, 2011 WL 3211364 (S.D.N.Y. July 27, 2011) ....................... 4

ii

Case 1:04-cv-01639-RJL Document 994 Filed 01/06/12 Page 4 of 26

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued) Page

In re REMEC, Inc. Sec. Litig., 702 F. Supp. 2d 1202 (S.D. Cal. 2010) ....................................................................................... 4 In re Westinghouse Sec. Litig., 90 F.3d 696 (3rd Cir. 1996) ........................................................................................................ 4 In re Williams Sec. Litig., 496 F. Supp. 2d 1195 (N.D. Okla. 2007), affd on other grounds, 558 F.3d 1130 (10th Cir. 2009)........................................................................................................................... 2 In re WorldCom, Inc. Sec. Litig., 352 F. Supp. 2d 472 (S.D.N.Y. 2005)......................................................................................... 5 *In re Worlds of Wonder Sec. Litig., 35 F.3d 1407 (9th Cir. 1994) .................................................................................................. 2, 6 *Janus Capital Grp., Inc. v. First Derivative Traders, 131 S. Ct. 2296 (2011) .................................................................................................... 3, 18, 19 *La. Sch. Emps. Ret. Sys. v. Ernst & Young, LLP, 622 F.3d 471 (6th Cir. 2010) .......................................................................................... 2, 12, 16 Lipsky v. Commonwealth United Corp., 551 F.2d 887 (2d Cir. 1976)........................................................................................................ 2 McCann v. Hy-Vee, Inc., No. 111459, 2011 WL 5924414 (7th Cir. Nov. 22, 2011)...................................................... 15 *Pub. Emps. Ret. Assn of Colo. v. Deloitte & Touche LLP, 551 F.3d 305 (4th Cir. 2009) ...................................................................................................... 2 SEC v. Johnson, 530 F. Supp. 2d 325 (D.D.C. 2008) ............................................................................................ 3 *SEC v. Price Waterhouse, 797 F. Supp. 1217 (S.D.N.Y. 1992)...................................................................................... 6, 12 *SEC v. Steadman, 967 F.2d 636 (D.C. Cir. 1992) .................................................................................................... 1 Stevens v. InPhonic, Inc., 662 F. Supp. 2d 105 (D.D.C. 2009) .......................................................................................... 16

iii

Case 1:04-cv-01639-RJL Document 994 Filed 01/06/12 Page 5 of 26

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued) Page

Thompson v. Linda & A., Inc., 779 F. Supp. 2d 139 (D.D.C. 2011) ............................................................................................ 4 Statutes 28 U.S.C. 1658(b)(2) ................................................................................................................. 15 Fed. R. Evid. 702 .......................................................................................................................... 14

iv

Case 1:04-cv-01639-RJL Document 994 Filed 01/06/12 Page 6 of 26

INTRODUCTION Plaintiffs spend much of their responsive papers fighting a motion KPMG did not make, in defense of a claim plaintiffs never filed. From the very first page, plaintiffs attack the professional competence of the KPMG auditors with an inflammatory Fannie Mae e-mail about the inadequacies of our KPMG audit team. Plaintiffs spend much of the remainder arguing that the accounting was wrong and that KPMGs audit procedures were not adequate, were executed inadequately or were lacking in due professional care. KPMG SUMF, Pl. Resp. 49, 51, 53, 57, 90, 107.1 They admit KPMG gave consideration to Fannie Maes aggressive goal of making $6.46 per share, KPMG SUMF, Pl. Resp. 59, but complain it did not do so properly, id. 37. They even devote a section to alleged deficiencies in KPMGs audits of other companies. Pl. Opp. III. But this case cannot be maintained based on breaches of professional competence. Plaintiffs claim fraud. To prove fraud, plaintiffs must submit evidence that the auditors intended fraud, or acted with such extreme recklessness that the danger of misleading investors was so obvious KPMG must have been aware of it. SEC v. Steadman, 967 F.2d 636, 641-42 (D.C. Cir. 1992) (internal quotation omitted). Attacks on professional competenceto wit, a

For conveniences sake, KPMG LLPs Statement of Undisputed Material Facts in Support of Its Motion for Summary Judgment, plaintiffs responsive filing (noted above), and KPMGs replies (where applicable) are included in a single document filed with this reply brief: KPMG LLPs Reply Regarding Its Statement of Undisputed Material Facts in Support of Its Motion for Summary Judgment (KPMG SUMF). References to plaintiffs responses to specific statements in KPMGs SUMF are identified in this brief as KPMG SUMF, Pl. Resp. __. KPMGs replies to plaintiffs responses to specific statements are identified in this brief as KPMG SUMF, Reply __. References herein to other memoranda or statements of fact follow the same format, inserting the subject matter (e.g., Pl. 133 Opp. or Pl. Loss Causation Opp.) or defendant (e.g., Pl. Howard Opp.). The Declaration of W.B. Markovits in Support of Lead Plaintiffs Memorandum in Opposition to KPMG, LLPs Motion for Summary Judgment is referred to herein as Markovits Opp. Decl.

Case 1:04-cv-01639-RJL Document 994 Filed 01/06/12 Page 7 of 26

malpractice claimcannot satisfy this requirement.2 Nor can plaintiffs satisfy their burden by arguing that someone else carried it for them. Plaintiffs quote heavily from allegations made by Fannie Mae in a complaint against KPMG, from allegations made by the SEC in a complaint against Fannie Mae, from the Paul Weiss Report, from the OFHEO Reports and from Fannie Maes restatement. They make no showing that such statements are evidence admissible against KPMG. As the D.C. Circuit succinctly put it, allegations are notoriously not evidence. Coward v. ADT Sec. Sys. Inc., 194 F.3d 155, 161 (D.C. Cir. 1999) (Williams, J., concurring in part and dissenting in part). Likewise, an SEC consent decree can not be used as evidence in subsequent litigation between that corporation and another party. Lipsky v. Commonwealth United Corp., 551 F.2d 887, 893 (2d Cir. 1976). But even these allegations do not go as far as plaintiffs do. In its complaint, Fannie Mae alleged malpractice, not fraud. Although the SEC complaint included claims under section 10(b), it made clear that those fraud claims were narrow, and did not include any conduct during the class period. Markovits Fannie Mae Decl. Ex. 24 (SEC Complaint 2, 52). And the SEC never brought a claim of any kind against KPMG. Plaintiffs cite nothing from any of these sources that even purports to say that the auditors acted with fraudulent intent. Only plaintiffs make that claim. Plaintiffs here have to present the evidence to prove it.3

In re IKON Office Solutions, Inc., 277 F.3d 658, 673 (3d Cir. 2002) (audit shortcomings do not raise an inference that [the auditor] harbored an intent to deceive or exhibited a reckless disregard for the likelihood of fraud); see also In re Worlds of Wonder Sec. Litig., 35 F.3d 1407, 1426 (9th Cir. 1994); La. Sch. Emps. Ret. Sys. v. Ernst & Young, LLP, 622 F.3d 471, 479 (6th Cir. 2010); Pub. Emps. Ret. Assn of Colo. v. Deloitte & Touche LLP, 551 F.3d 305, 313, 314 (4th Cir. 2009); In re Williams Sec. Litig., 496 F. Supp. 2d 1195, 1289 (N.D. Okla. 2007) 558 F.3d 1130, affd on other grounds, 558.F.3d 1130 (10th Cir. 2009); DSAM Global Value Fund v. Altris Software, Inc., 288 F.3d 385, 390, 391 (9th Cir. 2002).

3 Plaintiffs say this is not their burden, arguing that lack of scienter is an affirmative defense. Pl. Opp. 4. Scienter, however, is one of the elements of a securities fraud claim, on which plaintiffs bear the

Case 1:04-cv-01639-RJL Document 994 Filed 01/06/12 Page 8 of 26

Plaintiffs failure to do so is evident from the first. The dramatic e-mail with which they begin questions KPMGs professional competence (in plaintiffs words) but not its intent. Plaintiffs do not show that the document is evidence: it is plainly hearsay, and plaintiffs offer no reason to think it is admissible. They do not even lay a foundation for its authenticity. And on its face, the e-mail is from someone in Fannie Maes tax department discussing tax accounting. Plaintiffs have not made a claim about Fannie Maes taxes, much less a claim against KPMG. These failures are replete in plaintiffs responsive papers. They make a dramatic claim about KPMG and then fail to support it with evidence, or they cite an inflammatory statement and fail to tie it to KPMG. When the evidence is squarely against them, they try to change the subject, or ignore it altogether. Whatever else plaintiffs may accomplish with such tactics, they cannot show that KPMG acted fraudulently. Nor can they show that KPMG caused their losses. It should be uncontroversial after Janus that KPMG cannot be liable either to plaintiffs who purchased before KPMG made any statement, or to plaintiffs injured exclusively by the statements of others. But the failure of proof here goes further. In this fraud-on-the-market case, plaintiffs postulated a theory as to why the market might have reacted to the KPMG audit opinions, but they never put in the evidence to prove this is what happened. In their desire to put the biggest possible number on the table, they failed to put in any evidence against KPMG. For this reason, too, the claims against KPMG must be dismissed.

burden of proof. E.g. In re Acceptance Ins. Cos. Sec. Litig., 423 F.3d 899, 905 (8th Cir. 2005). Plaintiffs also claim that they need not set forth admissible evidence so long as the materials they cite are capable of being converted to admissible evidence, citing a footnote in SEC v. Johnson, 530 F. Supp. 2d 325, 333 n.13 (D.D.C. 2008). The court there permitted reliance on facts from deposition testimony and interview notes because it was clear both what the evidence was, and how it would be put into admissible form the author could testify at trial as to what the defendant told him. Plaintiffs do neither. They simply quote allegations and reports, without pointing to any evidence underlying them or showing how that unspecified evidence could be made admissible against KPMG.

Case 1:04-cv-01639-RJL Document 994 Filed 01/06/12 Page 9 of 26

ARGUMENT I. Plaintiffs Fail To Put Forward Evidence That KPMG Acted Fraudulently A. The Undisputed Evidence Is That KPMG Believed Its Audit Opinions

Plaintiffs do not dispute that, right or wrong, the KPMG auditors believed that Fannie Maes accounting policies were permissible. E.g., KPMG SUMF, Pl. Resp. 171. Every time plaintiffs say the auditors found a known departure from GAAP, the auditors also found the departure was immaterial. Plaintiffs do not dispute this either. Id. 85, 112.4 These concessions alone are sufficient to defeat any claim that the intent was fraud, as the Second Circuit recently made clear in Fait v. Regions Financial Corp., 655 F.3d 105, 113 (2d Cir. 2011). See also In re REMEC, Inc. Sec. Litig., 702 F. Supp. 2d 1202, 1243, 1251 (S.D. Cal. 2010) (granting summary judgment where statement of good faith rebutted any inference of scienter); In re Westinghouse Sec. Litig., 90 F.3d 696,712 (3rd Cir. 1996) (affirming dismissal of Section 10(b) claims where allegations failed to show the auditors could not reasonably and in good faith have opined); In re Lehman Bros. Sec. & ERISA Litig., Nos. 09 MD 2017, 08 Civ. 5523, 2011 WL 3211364, at *122-23 (S.D.N.Y. July 27, 2011) (plaintiffs must show the auditor did not actually hold the opinion it expressed or that it knew that it had no reasonable basis for holding it).5

Often, plaintiffs respond to a clearly undisputed fact with lengthy and argumentative statements that never dispute the fact stated or the evidence KPMG presented to support it. See, e.g., KPMG SUMF, Pl. Resp. 10, 115, 117, 126. That is not a proper response, and not sufficient in any event to dispute the fact. See Thompson v. Linda & A., Inc., 779 F. Supp. 2d 139, 146 (D.D.C. 2011) (bald denials do not create a genuine dispute); Hunter v. Rice, 480 F. Supp. 2d 125, 129-130 (D.D.C. 2007) (the court may assume that facts identified by the moving party in its statement of material facts are admitted, unless such a fact is controverted in the statement of genuine issues filed in opposition to the motion. (internal quotation omitted)).

5

The cases cited by plaintiffs make this same point. In AUSA Life Ins. Co. v. Ernst & Young, 206 F.3d 202 (2d Cir. 2000), the defendant auditors were liable because, believing the accounting was wrong, they still issued clean audit opinions. The evidence there showed that the auditors consistently noticed,

Case 1:04-cv-01639-RJL Document 994 Filed 01/06/12 Page 10 of 26

In response, plaintiffs try a new claim: KPMG was aware that Fannie Mae had engaged in multiple accounting improprieties, and even went so far as to internally suggest[] we summarize all of the items of the SEC rules that they do not fully comply with in case Fannie wanted us to [affirm] they were in full compliance with SEC rules. Pl. Opp. 10. The boldface type and the italics come from plaintiffs. The quotation is from an email KPMG partner Mark Serock sent to KPMG partner Harry Argires, dated February 21, 2002. But this is not evidence that there was any wrongdoing. Fannie Mae was not an SEC registrant on February 21, 2002. It did not register its securities with the SEC until over a year later. KPMG SUMF, Reply 282 (Registration of Securities dated March 31, 2003). Plaintiffs know this. It is in their Complaint. SAC 405. Mr. Serockthe only witness plaintiffs asked about this documentmade it abundantly clear. KPMG SUMF, Reply 283 (Supp. Ex. 121, Serock Tr. 539:17-540:2 (Q. At the time that you wrote this e-mail, was Fannie Mae an SEC registrant? A. No. Q. At the time that you wrote this e-mail, was Fannie Mae obligated to follow the SEC disclosure rules that -- to which you refer in this e-mail? A. No.)). When it comes to KPMGs performance of such an analysis in advance of Fannie Mae becoming a registrant, plaintiffs have nothing to say about it. KPMG SUMF, Reply 284 (KPMG Work Papers). Plaintiffs evidence not only fails to support a claim against KPMG, it shows KPMG

protested, and then acquiesced in misrepresentations that overstated revenue. 206 F.3d 202, 205 (2d Cir. 2000). The plaintiffs in Fine v. Am. Solar King Corp., 919 F.2d 290, 297 (5th Cir. 1990), submitted evidence that the auditors suspected the companys accounting was unreasonable and then stopped audit work in order to avoid finding out just how far off the mark the company was. This, the court found, exhibited a conscious purpose to avoid learning the truthfulness of a statement. Fine, 919 F.2d at 297. Likewise, the WorldCom court emphasized that there was no evidence the auditors had actually investigated the issues on which they stated a belief. In re WorldCom, Inc. Sec. Litig., 352 F. Supp. 2d 472, 497-98 (S.D.N.Y. 2005). In each case, the plaintiffs pointed to a record showing that the auditors could not have believed the statements they madethe opposite of what plaintiffs and their experts here have admitted.

Case 1:04-cv-01639-RJL Document 994 Filed 01/06/12 Page 11 of 26

was considering the effect these SEC rules might have on Fannie Maes public filings more than a year before they even applied. B. Plaintiffs Do Not Show Fraud In KPMGs Accounting And Auditing Judgments

In its motion papers, KPMG showed that, time and again, plaintiffs only criticism of KPMG was that it accepted an accounting policy that Fannie Mae later restated. KPMG pointed out that the kind of extreme recklessness necessary to support a claim of fraud against an outside auditor under the securities laws is not shown by evidence that the auditor interpreted the standard differently, or even wrongly. E.g., Worlds of Wonder, 35 F.3d at 1426; SEC v. Price Waterhouse, 797 F. Supp. 1217, 1240 (S.D.N.Y. 1992). In response, plaintiffs argue that this depends on whether the interpretation is credible, a question which can only be answered after trial. Pl. Opp. 19-21. No trial is necessary, however, when the answer to plaintiffs question is not fairly in dispute. 1. FAS 133

Plaintiffs own FAS 133 expert acknowledged that others had interpreted the standard, in the same way as KPMG, to allow a company to assume no ineffectiveness on a transaction when any ineffectiveness would be minimal. 133 SUMF, Reply 77-79 (Ernst & Young Manual); (Barron Tr.). Plaintiffs make a big point that there are people who agreed with their view, too. For instance, they do not dispute that a PricewaterhouseCoopers manual makes statements supporting Fannie Maes interpretation, but claim it runs counter to the SECs guidance on this exact issue, citing a speech by an SEC staff member in December 2006. See KPMG SUMF, Pl. Resp. 126. Plaintiffs not only ignore that the SEC staff changed their interpretation, KPMG SUMF 128, only a few months later (in the words of plaintiffs FAS 133 expert), they miss the point: the fact that there were independent professionals on both sides of the issue shows that 6

Case 1:04-cv-01639-RJL Document 994 Filed 01/06/12 Page 12 of 26

both interpretations were credible, a point made in detail in the White Paper.6 Unable to dispute this, plaintiffs make the specious argument that KPMG had no factual basis to accept that ineffectiveness was minimal, going so far as to claim the evidence is nearly fictitious. Pl. Opp. 15. The evidence is not fictitious. It is set out in the reply on defendants FAS 133 motion. Reply Mem. in Supp. of Defs. Joint Mot. for Partial Summ. J. Based on FAS 133 Accounting Issues (Defs. 133 Reply) Point III; see also KPMG SUMF, Reply 95, 111.7 Plaintiffs add nothing here, except to immediately contradict themselves by asserting that KPMG was intimately involved in the testing and validating of Fannie Maes hedging relationships. Pl. Opp. 15 n.70. And in their response to the FAS 133 Fact Statement, they unequivocally admit what they so loudly deny here: Lead Plaintiffs do not dispute that Fannie Maes FAS 133 team determined that if the difference in reset dates for the two sides of the hedging relationships was never more than seven days, any ineffectiveness would be insignificant. 133 SUMF, Pl. Resp. 48.8

Plaintiffs claim Deloitte & Touche reached conclusions based on its participation in the OFHEO investigation. Pl. Opp. 2 & n.7. Plaintiffs cite no actual statement by Deloitte. See KPMG SUMF, Reply 294 (Supp. Ex. 123, Maxant Tr. at 175:12-176:11 (agreeing that ); Supp. Ex. 124, Habayeb Tr. at 143:12-15 ( ); Supp. Ex. 120, Pimentel Tr. 143:2-4 ( )). Deloitte & Touche was one of the Big Four firms that signed the White Paper. Plaintiffs responses simply sidestep the statement. As noted in footnote 4 above, such a response does not raise a dispute but rather admits the underlying fact. Plaintiffs go on: Lead Plaintiffs do not dispute that Fannie Mae determined in a limited number of other areas that so long as certain terms of the hedged item and hedging instrument fit within highly constrained parameters, any ineffectiveness would always be inconsequential. 133 SUMF, Pl. Resp. 49. Plaintiffs argument that KPMG knew Fannie Mae was deliberately circumventing or ignoring its hedge accounting policy, Pl. Opp. 26, also is unsupported by the evidence, as explained in Defs. 133 Reply Point III.

7 8

Case 1:04-cv-01639-RJL Document 994 Filed 01/06/12 Page 13 of 26

To assert their case against KPMG, plaintiffs focus almost entirely on a single type of transaction, known as duration matching. See Pl. Opp. 13, 22-23. Out of the 30,000 hedging transactions during the class period, there were about 25 duration matches in each of 2001 and 2002, and only sixteen in the first eleven months of 2003. KPMG SUMF, Reply 285. Even within this narrow focus, plaintiffs succeed only in showing the profound disconnect between the arguments in their briefs and the evidence in the record. Indeed, the evidence shows the opposite of what plaintiffs say. Plaintiffs quote part of a sentence from a KPMG document stating such transactions are not in strict compliance with the letter of the standard, this is obviously a departure from that . . . Pl. Opp. 22-23. The end of the sentencewhich plaintiffs omitreads: as they dem[o]nstrate an immaterial departure. Markovits Opp. Decl. Ex. 27. Plaintiffs demonstrate, again, that the auditors believed the accounting proper and any departures immaterial.9 Plaintiffs claim that KPMG encountered significant push back over the testing of these hedges. Pl. Opp. 23. The KPMG work papers show, however, that far from turning a blind eye, KPMG had Fannie Mae test nearly half the duration matches from 2001. KPMG SUMF, Reply 286 (KPMG Work Papers). That is a large sample by any measure, and plaintiffs auditing expertwho is silent on the issuedoes not claim otherwise. For the 2002 hedges, two thirds of the total were tested, while of the duration matches entered into between January and November 2003 every one was tested. KPMG SUMF, Reply 287 (KPMG Work Papers). Consider the evidence, and plaintiffs succeed only in showing that KPMG resisted any significant push back

The same is true of the documents cited at Pl. Opp. 13 nn.60-61. In approving this policy, we stated in our hedge guidelines that we would test the hypothesis that ineffectiveness was immaterial on an annual basis. Our tests of hedges in 2001 and 2002 confirmed our belief. Markovits Opp. Decl. 31, Ex. 12 at 1; see also Markovits Opp. Decl. 117, Ex. 64 at 1.

Case 1:04-cv-01639-RJL Document 994 Filed 01/06/12 Page 14 of 26

from its clientand in showing that the testing was not fictitious. Plaintiffs try again with a 1999 document describing as aggressive Fannie Maes use of 15 basis points (up from ten) as a de minimis threshold for these hedges. Pl. Opp. 23. But the quoted sentence did not end where plaintiffs put the period. It continued: and KPMG intends to monitor closely the I/S [income statement] impact of this new policy and may propose audit differences in specific instances. Markovits Opp. Decl. Ex. 29. As noted above, a substantial percentage of the duration matches were actually tested, including the de minimis calculations. None of them reached even ten points. Again, the evidence not only fails to support plaintiffs arguments, but negates them. In the end, plaintiffs are left making an argument that may well be unprecedented in the history of the federal securities laws: that their expert determined Fannie Mae with KPMGs guidance and approval designed and implemented a hedge accounting policy that violated FAS 133 in the service of the Companys mission to portray the economic business realities underlying those transactions. Pl. Opp. 16 (emphasis added). Whether accurately portraying the economic business realities underlying transactions is a misguided mission, or instead the very purpose of the securities laws, it is the very opposite of an intent to defraud. 2. FAS 91 and FAS 115

Plaintiffs claim, with no citation of evidence whatsoever, that KPMG knew that FAS 91 did not allow for a precision threshold concept. Pl. Opp. 24. Here they ignore the testimony of their own auditing expert, and their response to KPMGs statement of material facts, both conceding that KPMG believed the policy was a reasonable application of FAS 91. KPMG SUMF, Pl. Resp. 171. Plaintiffs also ignore their own FAS 91 expert, who acknowledged that the FAS 91 policy may have been appropriate for use by KPMG . . . auditing literature supports

Case 1:04-cv-01639-RJL Document 994 Filed 01/06/12 Page 15 of 26

this concept. Id. 170. The only dispute is between plaintiffs arguments and their own experts.10 Moreover, while plaintiffs contest whether a precision threshold was proper, they do not dispute the facts that underlay the threshold: that independent, reputable dealers came up with different estimates of pre-payment speeds, that any of these estimates was reasonable, and that the spread between them equaled the original precision threshold. KPMG SUMF, Pl. Resp. 149-151. They instead argue that there is no evidence KPMG ever reevaluated that relationship. Pl. Opp. 19. That is untrue, and KPMG put in the only evidence directly on this point. KPMG SUMF 161-165. Likewise, plaintiffs claim that KPMG never considered the effect of the threshold. Pl. Opp. 18. But the effect is right there in the audit work, where the auditors reviewed the catchup calculations and compared them to the precision threshold. KPMG SUMF, Pl. Resp. 159160; see also id. 161-165. Plaintiffs admit their audit expert had no problem identifying the numbers. Id. 158. And their FAS 91 expert said these numbers were quantitatively immaterial to a company Fannie Maes size. Id. 155; see also id. 150-152, 154, 156, 158.11 Again, plaintiffs arguments are contradicted by the evidence and the testimony of their own experts. The same plaintiffs expert explained, in some detail, that whatever the flaws in the companys FAS 115 policy, it could not have been used to manipulate Fannie Maes quarterly

10

Plaintiffs also argue KPMG knew that Fannie Mae was deliberately circumventing its FAS 91 policy. Pl. Opp. 25. This new claim is unsupported by the evidence, as explained at pages 25-28 of KPMG LLPs Opposition to Lead Plaintiffs Motion for Partial Summary Judgment Against KPMG.

Plaintiffs responses to the admissions of their own expert sidestep the statements. As noted in footnote 4 above, such a response does not raise a dispute but rather admits the underlying fact.

11

10

Case 1:04-cv-01639-RJL Document 994 Filed 01/06/12 Page 16 of 26

earningsFAS 115 just does not work that way. KPMG SUMF 195-196.12 Plaintiffs keep making the claim anyway, featuring it prominently on the very first page of another opposition brief. See Pl. 133 Opp. 1 (Need some flexibility to shift earnings between quarters? Dont worry; the Company can reclassify securities at the end of the month if necessary (FAS 115 violation).). They provide no citation there either, nor do they make mention of their own experts sworn testimony contradicting their claim. 3. Reviewing Fannie Maes Accounting Policies Prior to Implementation Was Not Fraud

Turning their own claims upside-down, plaintiffs argue that because KPMG worked hard to understand the accounting policies, it must have had fraudulent intent. Pl. Opp. 8. They point to evidence that before Fannie Mae implemented a new accounting policy, it asked the auditors whether they believed the policy was a reasonable application of GAAP. Pl. Opp. 10. Plaintiffs audit expert testified, however, that there was nothing wrong with that: Q. Okay. So theres nothing wrong with telling the client at some point before the standard is actually implemented that the accounting firm agrees with the proposed accounting? A. . . . I dont think it would be a problem. KPMG SUMF, Reply 296 (Ex. 2, Berliner Tr. at 436:16-438:8). Again, plaintiffs are at odds with their experts.13

12

All plaintiffs say in response is that the accounting did not comply with FAS 115. They do not even attempt to explain how Fannie Maes securities designations under FAS 115 could be used to manipulate quarterly earnings, or point to any evidence that they were. Plaintiffs also quote Mr. Howard stating that KPMG provided extensive technical assistance on the front end of structuring products and transactions to ensure optimal accounting treatment and economic results. Pl. Opp. 10 (emphasis omitted) (quoting Markovits Opp. Decl. Ex. 6, Feb. 15, 2000 Audit Committee Meeting Minutes). However, plaintiffs claims have nothing to do with Fannie Maes products and transactions, and they do not identify any such items that were accounted for improperly.

13

11

Case 1:04-cv-01639-RJL Document 994 Filed 01/06/12 Page 17 of 26

Any suggestion that KPMGs prior review of Fannie Maes accounting policies led KPMG to subvert its judgment cannot withstand the undisputed record that KPMG sometimes disagreed with Fannie Maes accounting, and was willing to say so. KPMG said no when the stakes were high, requiring Fannie Mae to record billions in losses on its financial statements during the class period. KPMG SUMF 116-123. KPMG said no even when it had previously said yes in its prior review. KPMG SUMF 124-125; cf. KPMG LLPs Mem. of P. & A. in Supp. of Its Mot. for Summ. J. (KPMG Mem.) at 34-35 (listing examples). Plaintiffs make no attempt to reconcile these undisputed facts with their arguments. C. The Fees KPMG Received Do Not Show Fraudulent Intent

Plaintiffs try to find evidence of fraudulent intent in KPMGs fees. The courts squarely reject the notion that audit fees can show fraudulent intent.14 Plaintiffs imply that KPMG had bad intent, however, because it allegedly re-categorized fees to cover up the amounts received for non-audit services. Pl. Opp. 28-29. The undisputed facts show otherwise. KPMGs fees were set out in Fannie Maes proxy statements. KPMG SUMF, Reply 289-290 (Proxy Statements). Those proxy statements not only set forth KPMGs fees by category, but also described the type of services within each category. Even when the types of services included within certain categories changed between 2001 and 2002, their descriptions remained every bit as detailed. KPMG SUMF, Reply 290. KPMGs fees and the nature of its

They do not (and cannot) claim that KPMG came up with the hedges in the DAG manual or the methodology used in assessing the FAS 91 estimates. The record shows otherwise. E.g. Fidel v. Farley, 392 F.3d 220 (6th Cir. 2004) ([A]llegations that the auditor earned and wished to continue earning fees from a client do not raise an inference that the auditor acted with the requisite scienter.); see also La. Sch. Emps. Ret. Sys., 622 F.3d at 484 (Even a specific account that was one of the auditors most lucrative would not imply scienter on the part of the auditor.); Price Waterhouse, 797 F. Supp. at 1242 (declining to look with a jaundiced eye at each accounting decision made during a complex audit merely because of an accountants economic motivation in maintaining an ongoing relationship with a client).

14

12

Case 1:04-cv-01639-RJL Document 994 Filed 01/06/12 Page 18 of 26

services also were reported to OFHEO, which did not question the firms independence. See, e.g., KPMG SUMF, Reply 293 (2002 Annual Report to Congress). These plain and public disclosures to investors and to Fannie Maes regulator leave any claim about a cover up nonsensical. See Defs. 133 Reply Point II. Tellingly, plaintiffs never contest the correctness of the re-categorization of fees. Their auditing expert wasnt able to research [the re-categorization] to reach a conclusion. KPMG SUMF, Reply 290 (Ex. 2, Berliner Tr. at 555:21-556:10); id. (Ex. 2, Berliner Tr. at 556:11-14) (Q. So the only criticism you have related to the categorization is that it was not the same in all three years? A. Yes.). In fact, the classification followed guidance from the SEC. KPMG SUMF, Reply 291 (KPMG Correspondence). Fees paid to Fannie Maes current auditor are categorized the same way to this day. KPMG SUMF, Reply 292 (Fannie Mae 2010 10K). D. Plaintiffs Contradictory Arguments About Earnings Manipulation Prove Nothing

Plaintiffs try to find evidence of KPMGs fraudulent intent in Fannie Maes goal of doubling its 1998 earnings to $6.46 in 2003. As KPMG acknowledged, this could put pressure on management to use aggressive accounting policies and other means to achieve this growth. Pl. Opp. 32. Plaintiffs go so far as to say their audit expert concluded that Fannie Mae was misstating its earnings from 2001 to 2003 so that it could meet the $6.46 pledge and [t]hats why they had to restate. Pl. Opp. 32 (alteration in original) (quoting Berliner Tr). In fact, that is the over-arching theory of plaintiffs case. The problem with the theory, however, is that the numbers prove it wrong. The Companys earnings, even after the restatement corrected the financial statements, were

13

Case 1:04-cv-01639-RJL Document 994 Filed 01/06/12 Page 19 of 26

approximately $8.00 per share, beating the $6.46 goal by a large margin.15 Plaintiffs cannot raise a genuine issue for trial by having their expert make a statement that is completely unsupported, and flatly contradicted, by the evidence. See Brooke Grp. Ltd. v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp., 509 U.S. 209, 242 (1993) (suggesting summary judgment appropriate where an expert opinion is not supported by sufficient facts, or where indisputable facts on the record contradict opinion or otherwise render it unreasonable); see also Fed. R. Evid. 702 (expert opinion testimony based on insufficient facts or data, or on unsupported suppositions is not admissible). Their efforts succeed only in digging a deeper hole. Opposing the Individual Defendants motions, plaintiffs admit that Fannie Mae used debt repurchases to reduce earnings by $2.30 per share in 2003, the same year it was supposedly committing a fraud in order to inflate those earnings. See, e.g., Raines SUMF, Pl. Resp. 40. Plaintiffs overarching theory that Fannie Mae needed to misstate earnings to meet the $6.46 pledge and [t]hats why they had to restateis thus entirely without support.16 Plaintiffs also assert that that Fannie Mae management miraculously met the EPS goals almost to the exact penny for the maximum AIP bonus payout year after year during the Class Period. Pl. Opp. 33 (emphasis added). Once again, the numbers prove them wrong. The chart to which plaintiffs refer (reprinted in the oppositions to the motions of the individual defendants, see, e.g, Pl. Howard Opp. 14) shows that Fannie Mae beat the maximum by a lot in 2001 (27

15

Plaintiffs expert admitted he had not known this fact, which plaintiffs struggle to avoid but cannot dispute. KPMG SUMF, Pl. Resp. 68-69. This expert further testified that the goal was not excessively aggressive and that he could not even say whether it was realistic, matters plaintiffs do not deny. Id. 65, 67. Plaintiffs neither escape this testimony nor put in admissible evidence against KPMG merely by changing the adverb to unduly, the phrase they repeat throughout their brief. Plaintiffs also cite a speech by Sam Rajappa, the head of Internal Audit, on the $6.46 goal, which they admit KPMG never knew about. Pl. Opp. 33 n.164; KPMG SUMF, Reply 297. A speech that KPMG never heard cannot show KPMG intended fraud.

16

14

Case 1:04-cv-01639-RJL Document 994 Filed 01/06/12 Page 20 of 26

cents), beat it by a little in 2002 (2.6 cents), and missed it in 2003 (by 2.9 cents). Plaintiffs do not even show a pattern during the class period, much less a miraculous one. So plaintiffs reach back to 1998, years before the Class Period began, complaining about an adjustment to the FAS 91 estimate made under a different methodology and considered by different KPMG auditors.17 Pl. Opp. 29-32. They make no effort to explain how such claims can show that the auditors here intended fraud. The most that plaintiffs demonstrate is why the federal securities laws include a five-year statute of repose, and why it was made absolute.18 E. Plaintiffs Reliance on the Restatement Is Equally Unavailing

Plaintiffs arguerepeatedlythat scienter can be inferred from the numbers alone. Fannie Mae restated 30 accounting policies. Pl. Opp. 2, 10-42. The company had 2,500 internal control weaknesses at the end of 2004. Id. 2, 38. The restatement resulted in the erasure of billions in assets and earnings. Id. 2, 42. Numbers alone, however, do not show that an auditor acted with fraudulent intent. E.g., In re Fannie Mae Sec. Litig., 503 F. Supp. 2d 25, 41 (D.D.C. 2007) (Allowing an inference of scienter based on the magnitude of fraud would eviscerate the principle that accounting errors alone cannot justify a finding of scienter. (quoting Fidel, 392 F.3d at 231)); Dronsejko v. Grant Thornton, 632 F.3d 658, 668-69 (10th Cir. 2011) (The magnitude of [a] restatement has nothing to do with a defendants scienter where, presumably, the restatement would have been equally large had [the defendant] acted in good

17

The audit partners in 1998 were Kenneth Russell and Julie Theobald. KPMG SUMF 26 (Russell Tr.); KPMG SUMF, Reply 295 (Theobald Tr.). The audit partners for the 2001 to 2003 audits were Mark Serock and Harry Argires, neither of whom worked on the 1998 audit. KPMG SUMF 27 (Serock Tr.), 31 (Argires Tr.).

28 U.S.C. 1658(b)(2); McCann v. Hy-Vee, Inc., No. 111459, 2011 WL 5924414, at *3-5 (7th Cir. Nov. 22, 2011) (statute creates an unyielding and absolute barrier). KPMG was first named as a defendant in this action over seven years after the 1998 financial statements were published. KPMG SUMF, Reply 298.

18

15

Case 1:04-cv-01639-RJL Document 994 Filed 01/06/12 Page 21 of 26

faith, negligently, recklessly, or, for that matter, intentionally.).19 Yet the numbers alone are all the evidence that plaintiffs provide. They make no effort to explain what the error was (with very few exceptions) or how it occurred. They admit that, despite what must be one of the largest records assembled in any civil litigation, their experts could not find sufficient documentation to address those questions. KPMG SUMF, Pl. Resp. 253; see also id. 245. Their auditing expert says nothing about how KPMG audited these other issues, or what it purportedly did wrong. In place of evidence, plaintiffs substitute rhetoric: [T]he only plausible way that Fannie Maes financial statements could suffer from such significant GAAP violations in so many critical accounting areas is that KPMG was only rubber stamping Fannie Maes accounting policies. Pl. Opp. 41 (emphasis added) (quoting Berliner Rep.). As the decisions cited above show, this kind of argument is no substitute for evidence of fraudulent intent. There is no reason to reach a different answer here. Plaintiffs do not dispute that these other issues included accounting policies that had been shared with, and approved by, the staff of the SEC. KPMG SUMF, Pl. Resp. 211. They do not dispute they included policies reviewed and approved by another Big Four accounting firm. Id. 209, 212. They admit that among these issues, Fannie Mae later concluded that its Class Period accounting was better, and went back to it. Id. 215. In their responsive papers, plaintiffs add another to this list, claiming errors

19

See also Stevens v. InPhonic, Inc., 662 F. Supp. 2d 105, 119 (D.D.C. 2009) (rejecting plaintiffs argument that fraud could be inferred from a restatements magnitude, otherwise any publicly traded company that restated would be at risk of being hauled into court to atone for its actions, even if no facts are alleged to suggest it was caused by anything other than innocent mistakes); La. Sch. Emps. Ret. Sys., 622 F.3d at 484-85 (A statement such as there was a problem does not tell us whether [the auditor] fraudulently refused to see the obvious. . . . [T]he fact that the statements later turned out to be false is irrelevant.); In re Ceridian Corp. Sec. Litig., 542 F.3d 240, 246 (8th Cir. 2008) (affirming district courts rejection of contention that the sheer number of violations, and the magnitude of the restatements, give rise to an inference to that defendants were at least severely reckless).

16

Case 1:04-cv-01639-RJL Document 994 Filed 01/06/12 Page 22 of 26

occurred because facts were withheld from the Class Period auditors. Pl. Spencer Opp. at 15; Pl. Howard Opp. 16. Moreover, plaintiffs do not dispute that KPMG said no to its client on numerous occasions, on issues that were significant for the company, and even in circumstances where the FASB later said the auditors were being too restrictivethe very antithesis of the rubber stamping plaintiffs claim. KPMG SUMF, Pl. Resp. 116-125; cf. KPMG Mem. at 3435. Plaintiffs make no effort to support their claim with evidence, just as they make no effort to square the evidence with their claim. Even the claimed erasure of billions of dollars in earnings evaporates in the light of the evidence. This erasure relates overwhelmingly to a single issue, whether the company qualified for hedge accounting. Pl. Opp. 2, 42. Plaintiffs cannot avoid the fact that these losses were disclosed throughout the Class Period, or that the change in accounting treatment said nothing about the economics of the hedges. KPMG SUMF, Pl. Resp. 9; 133 SUMF 64, 74, 76. On this there can be no disagreement, a point that Donald Nicolaisen, then Chief Accountant at the SEC, made over and over again in response to plaintiffs questions. KPMG SUMF, Reply 288 (Supp. Ex. 122, Nicolaisen Tr. at 108:2-5 ([T]he information is actually in the financial statements as to losses that are deferred on hedging contracts.); id. 108:15-19 (End of the day net zero, its the periods in which the gains and losses are recognized for accounting purposes. Its different than the economics of the transaction.); see also id. 118:1-2 (I did not conclude that the economics of Fannie Maes activities were improper in any way.)).20 The evidence not only fails to support plaintiffs rhetoric, but demonstrates why numbers alone cannot show fraud.

20

As they have throughout this case, plaintiffs invoke the statement of Mr. Nicolaisen that Fannie Maes FAS 133 policy was not even on the page. Pl. Opp. 12. Apparently, they want to argue that this means Mr. Nicolaisen found the policy so obviously wrong that no reasonable person could have accepted it. Defendants have thoroughly debunked the notion that Mr. Nicolaisen was expressing such an opinion when he made that comment. See Defs. 133 Reply 13-15.

17

Case 1:04-cv-01639-RJL Document 994 Filed 01/06/12 Page 23 of 26

F.

Criticism of Other KPMG Audits Is Not Evidence of Scienter Here

Left with nothing in the record proving KPMGs scienter, plaintiffs resort to talking about criticisms of KPMGs audits of other companies. Pl. Opp. 44-45. This effort fails as well. The earliest of these documents was published after the last audited financial statement at issue in this litigation. See id. 45 nn.219-225. They are irrelevant, even under the standard plaintiffs advance. II. Plaintiffs Do Not Meaningfully Oppose KPMGs Motion for Summary Judgment on Loss Causation and Damages According to plaintiffs, KPMG argues that it can only be liable for its misrepresentations under the federal securities laws. Pl. Loss Causation Opp. 50 (emphasis in original). KPMG did not come up with that statement: it is the law set forth by the United States Supreme Court. Janus Capital Grp., Inc. v. First Derivative Traders, 131 S. Ct. 2296 (2011). It is undisputed that the only public statement[s] KPMG made that plaintiffs allege were materially misleading were its audit opinions, the first of which was made in April 2002. KPMG SUMF, Pl. Resp. 259-260. That means KPMG cannot be liable to people who purchased before April 2002. Inexplicably, plaintiffs call this something to be resolved by the jury. Pl. Loss Causation Opp. 50. They appear to mistake the issue as one of proportionate liability under the securities laws. Id. It is not. A class member who purchased stock before KPMG made any statement simply has no claim against KPMGthat is what Janus decided. Likewise, KPMG cannot be liable to people who purchased from October to December 2004, since plaintiffs do not dispute that they attribute those losses to statements by others. KPMG SUMF, Pl. Resp. 276-277. This too, they claim, is a question for the jury, though again they identify nothing to decide. When plaintiffs attribute particular losses to particular statements by others, there is nothing for a jury to apportion. Similarly, KPMG pointed out that 18

Case 1:04-cv-01639-RJL Document 994 Filed 01/06/12 Page 24 of 26

it cannot be liable for the alleged stock inflation in July 2003, since plaintiffs also attribute that inflation to statements by others. Again, plaintiffs do not dispute this. Id. 273. Here, plaintiffs do not even respond. There may be a reason plaintiffs fight so hard to avoid the holding in Janus. It is the thread that unravels their claims against KPMG. Plaintiffs concede that nothing KPMG said caused Fannie Maes stock price to increase. KPMG SUMF, Pl. Resp. 261, 264, 267, 269277 (admissions that no inflation entered the stock as the result of any of KPMGs audit opinions). They cannot show a later decline in the stock price came from some correction of a statement by KPMG, as opposed to coming from anyone or anything else, because their expert refused to tie any such decline to KPMGs statements. Loss Causation SUMF 17 (Jarrells admission that he did nothing to apportion the impact of different things going on in the stock price on the corrective disclosure dates). Plaintiffs have a theory as to why a KPMG statement might have caused their losses, but it is only a theory. That is not sufficient to survive a motion for summary judgment.21 This failure of proof is clearly shown in plaintiffs admitted refusal to disentangle any impact of the 1998 accounting. Plaintiffs do not sue KPMG over that accounting, because any such claim would have long been time-barred. See n.18, above. Faced with the problem created by their failure to disentangle this issue, plaintiffs try to downplay it as a comparatively small example of earnings manipulation that took place. Pl. Loss Causation Opp. 35. The claim is

21

Plaintiffs cannot recover from this complete failure of proof against KPMG by arguing that it maintained price inflation. No such opinion appears in their experts reports, which explains why they do not cite to Professor Jarrells report when advancing this theory. Pl. Loss Causation Opp. 25-29. They cite no evidence from which a jury could determine whether or not any particular KPMG statement maintained price inflation in any particular amount, or at all, and plaintiffs cite no case accepting a maintenance theory in the absence of a factual record.

19

Case 1:04-cv-01639-RJL Document 994 Filed 01/06/12 Page 25 of 26

disingenuous. Their own damages expert cited one report after another focusing on exactly that allegation. KPMG SUMF, Reply 281 (Jarrell Rep.); see also Loss Causation SUMF, Pl. Resp. Part II, 81 (not disputing article describing claim as the most damaging part of the report). Plaintiffs themselves call this 1998 issue [o]ne of the most egregious examples in their responsive papers. Pl. Opp. 29. Every other response discusses it several times. Pl. Raines Opp. 16-18, 29-30; Pl. Howard Opp. 23-25, 36-37; Pl. Spencer Opp. 20-22, 31-32. Plaintiffs cannot avoid the problem by making self-contradictory arguments. CONCLUSION For the reasons stated above and in KPMGs opening brief, the Court should grant summary judgment on all of plaintiffs claims against KPMG. DATED: December 28, 2011 Respectfully submitted, ____/s/_F. Joseph Warin_____ F. Joseph Warin (D.C. Bar No. 235978) Scott Fink (pro hac vice) John H. Sturc (D.C. Bar No. 914028) George H. Brown (pro hac vice) Andrew S. Tulumello (D.C. Bar. No. 468351) David Debold (D.C. Bar No. 484791) Monica K. Loseman (pro hac vice) GIBSON, DUNN & CRUTCHER LLP 1050 Connecticut Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 Telephone: (202) 955-8500 Facsimile: (202) 467-0539 Counsel for Defendant KPMG LLP

20

Case 1:04-cv-01639-RJL Document 994 Filed 01/06/12 Page 26 of 26

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE I hereby certify that on December 28, 2011, I electronically mailed the foregoing KPMG LLPS REPLY MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF ITS MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT to the Court and the below-listed counsel of record. Bill Markovits James R. Cummins Melanie S. Corwin Waite, Schneider, Bayless & Chesley Co., L.P.A. 1513 Fourth & Vine Tower One West Fourth Street Cincinnati, OH 45202 Counsel for Lead Plaintiffs Jeffrey W. Kilduff Robert M. Stern

Michael J. Walsh, Jr.

Daniel S. Sommers Cohen, Milstein, Hausfeld & Toll P.L.L.C West Tower, Suite 500 1100 New York Ave., N.W. Washington, D.C. 20005 Counsel for Plaintiffs

OMelveny & Myers LLP 1625 Eye Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20006-4001 Counsel for Defendant Fannie Mae Kevin M. Downey Alex G. Romain Joseph M. Terry, Jr. Williams & Connolly LLP 725 Twelfth Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20005-5091 Counsel for Defendant Franklin D. Raines

David S. Krakoff Christopher F. Regan Adam B. Miller BuckleySandler LLP 1250 24th Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20037 Counsel for Defendant Leanne G. Spencer Steven M. Salky Eric R. Delinsky Zuckerman Spaeder LLP 1800 M Street, N.W., Suite 1000 Washington, D.C. 20036-5807 Counsel for Defendant J. Timothy Howard Joseph J. Aronica Duane Morris LLP Suite 1000 505 9th Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20004-2166 Counsel for FHFA /s/ _Lissa M. Percopo

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Sol. Man. Chapter 4 Consol. Fs Part 1Dokument37 SeitenSol. Man. Chapter 4 Consol. Fs Part 1itsmenatoy43% (7)

- Safal Niveshak Stock Analysis Excel Version 4.0Dokument37 SeitenSafal Niveshak Stock Analysis Excel Version 4.0Neeraj KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Practical Accounting 2Dokument6 SeitenPractical Accounting 2Jessica Marie B. Mendoza0% (1)

- DTR TransmittalDokument12 SeitenDTR TransmittalANGIE BERNALNoch keine Bewertungen

- 6 May 05 - Deposition of John Arnold of EnronDokument8 Seiten6 May 05 - Deposition of John Arnold of Enronny1davidNoch keine Bewertungen

- 31 May 2001 - Deposition of John Arnold of EnronDokument14 Seiten31 May 2001 - Deposition of John Arnold of Enronny1davidNoch keine Bewertungen

- GSE Reform and A Conspiracy of Silence Draft 1.3.1Dokument11 SeitenGSE Reform and A Conspiracy of Silence Draft 1.3.1ny1davidNoch keine Bewertungen

- KPMG Letter To SEC On FAS 133Dokument52 SeitenKPMG Letter To SEC On FAS 133ny1davidNoch keine Bewertungen

- HUD OIG Interview of Stephen Blumenthal of OFHEODokument28 SeitenHUD OIG Interview of Stephen Blumenthal of OFHEOny1david100% (1)

- GSE Reform and A Conspiracy of Silence Draft 1.4Dokument36 SeitenGSE Reform and A Conspiracy of Silence Draft 1.4ny1david100% (3)

- KPMG Work Paper On Fannie's HedgingDokument4 SeitenKPMG Work Paper On Fannie's Hedgingny1davidNoch keine Bewertungen

- FHFA V Credit SuisseDokument122 SeitenFHFA V Credit Suisseny1davidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fannie Ofheo 091704Dokument211 SeitenFannie Ofheo 091704David FidererNoch keine Bewertungen

- FHFA V Morgan StanleyDokument110 SeitenFHFA V Morgan Stanleyny1davidNoch keine Bewertungen

- FHFA V CountrywideDokument178 SeitenFHFA V Countrywideny1david100% (2)

- Bank of America Corporation: United States Securities and Exchange Commission Form 8-KDokument5 SeitenBank of America Corporation: United States Securities and Exchange Commission Form 8-Kny1davidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fannie Special Exam May 2006Dokument348 SeitenFannie Special Exam May 2006ny1davidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Donald Nicoliasen Deposition On FAS 133Dokument7 SeitenDonald Nicoliasen Deposition On FAS 133ny1davidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Po22072001 PDFDokument1 SeitePo22072001 PDFchanna abeygunawardanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- LCCI Accounting Concepts-1Dokument51 SeitenLCCI Accounting Concepts-1Khin Lay HtetNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fixed Assets PDFDokument21 SeitenFixed Assets PDFSrihari GullaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Full Download:: Suggested Answers To Discussion QuestionsDokument8 SeitenFull Download:: Suggested Answers To Discussion QuestionsIrawatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 0157 20230901 Motion To Comply With The August 14 RO Final CombinedDokument86 Seiten0157 20230901 Motion To Comply With The August 14 RO Final CombinedMetro Puerto RicoNoch keine Bewertungen

- ACCT 504 Midterm Exam 2Dokument7 SeitenACCT 504 Midterm Exam 2DeVryHelpNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sarangapani & Co: Chartered AccountantsDokument14 SeitenSarangapani & Co: Chartered AccountantsSarangapani KaliyamoorthyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Accounting Equation and The Double-Entry SystemDokument24 SeitenThe Accounting Equation and The Double-Entry SystemJohn Mark MaligaligNoch keine Bewertungen

- UAS ALK Dinda Azzahra Salsabilla Contoh Forecasting and Valuation AnalysisDokument9 SeitenUAS ALK Dinda Azzahra Salsabilla Contoh Forecasting and Valuation AnalysisDinda AzzahraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vipshop We Are Not Buying The Financial Statements - Vipshop Holdings (NYSE VIPS) Seeking AlphaDokument91 SeitenVipshop We Are Not Buying The Financial Statements - Vipshop Holdings (NYSE VIPS) Seeking Alphapetertang2003Noch keine Bewertungen

- D31CG Unit 3 2014aDokument32 SeitenD31CG Unit 3 2014aSithick MohamedNoch keine Bewertungen

- PETRONAS PIR2021 Financial Report 2021Dokument174 SeitenPETRONAS PIR2021 Financial Report 2021Ez BzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dry RunDokument5 SeitenDry RunMarc MagbalonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Accounting For Merchandising Operations: Weygandt - Kieso - KimmelDokument62 SeitenAccounting For Merchandising Operations: Weygandt - Kieso - KimmelMaidah NaeemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Financial Accounting Vs Management AccountingDokument2 SeitenFinancial Accounting Vs Management AccountingMuhamamd Asfand YarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Digital AccountingDokument45 SeitenDigital AccountingSodikoHidayadNoch keine Bewertungen

- International Accounting 3Rd Edition Doupnik Test Bank Full Chapter PDFDokument40 SeitenInternational Accounting 3Rd Edition Doupnik Test Bank Full Chapter PDFJulieHaasyjzp100% (9)

- Overheads: Faculty: Zaira AneesDokument59 SeitenOverheads: Faculty: Zaira AneesVishal MalhiNoch keine Bewertungen

- College of Accountancy: Lesson 1 - Concepts of CapitalDokument4 SeitenCollege of Accountancy: Lesson 1 - Concepts of Capitalfirestorm riveraNoch keine Bewertungen

- AccDokument13 SeitenAccNazmul HasanNoch keine Bewertungen

- End Beginning of Year of Year: Liquidity of Short-Term Assets Related Debt-Paying AbilityDokument4 SeitenEnd Beginning of Year of Year: Liquidity of Short-Term Assets Related Debt-Paying Abilityawaischeema100% (1)

- Session Ending Examination 2019Dokument7 SeitenSession Ending Examination 2019madhudevi06435Noch keine Bewertungen

- AccountingDokument6 SeitenAccountingaya walidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Principles of Accounting - Module Information PackDokument6 SeitenPrinciples of Accounting - Module Information PackHaider QureshiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Six Sigma Project - Gaurav SinghDokument18 SeitenSix Sigma Project - Gaurav SinghVarun GhaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mary Anne C. Bantog: ObjectiveDokument4 SeitenMary Anne C. Bantog: ObjectiveUWatch TVNoch keine Bewertungen