Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Rostow

Hochgeladen von

sugata senOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Rostow

Hochgeladen von

sugata senCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Rostow's Stages of Growth

The Rostow's Stages of Growth model is one of the major historical models of economic growth. Rostow's model is a part of the liberal school of economics, laying emphasis on the efficacy of modern concepts of free trade and the ideas of Adam Smith. Rostows model does not disagree with John Maynard Keynes regarding the importance of government control over domestic development which is not generally accepted by some ardent free trade advocates. The basic assumption given by Rostow is that countries want to modernize and grow and that society will agree to the materialistic norms of economic growth. The model postulates that economic growth occurs in five basic stages, of varying length: 1. 2. 3. 4. Traditional society Preconditions for take-off Take-off Drive to maturity 5. Age of High mass consumption Rostow's model is one of the structuralist models of that countries go through each of these stages fairly linearly, and set out a number of conditions that were likely to occur in investment, consumption and social trends at each state. Not all of the conditions were certain to occur at each stage, however, and the stages and transition periods may occur at varying lengths from country to country, and even from region to region. Traditional societies An economy in this stage has a limited production function which barely attains the minimum level of potential output. This does not entirely mean that the economy's level is static. States and individuals utilize irrigation systems in many instances, but most farming is still purely for subsistence. There have been technological innovations, but only on ad hoc basis. All this can result in increases in output, but never beyond an upper limit which cannot be crossed. Lacking modern science and technology, such innovation as through barter, and the monetary system is not well developed. Investment's share never exceeds 5% of total economic production. Wars, famines and epidemics cause initially expanding populations to halt or shrink, limiting the single greatest factor of production: human manual labor. Volume fluctuations in trade due to political instability are frequent; historically, trading was subject to great risk and transport of goods and raw materials was expensive, difficult, slow and unreliable. In this stage, some regions are entirely self-sufficient. Pre-conditions to take-off In the second stage of economic growth the economy undergoes a process of change for building up of take off. This pattern was followed in Europe, parts of Asia, the Middle East and Africa. There is also a second pattern in which he said that there was no need for change in socio-political structure because these economies were not deeply caught up in older, traditional social and political structures. The only changes required were in economic and technical dimensions. The nations which followed this pattern were in North America and Oceania (New Zealand & Australia). There are three important dimensions to this transition: firstly, the shift from an agrarian to an industrial or manufacturing society begins, albeit slowly. Secondly, trade and other commercial activities of the nation broaden the market's reach not only to neighboring areas but also to far-flung regions, creating international markets. Lastly, the surplus attained should not be wasted on the conspicuous consumption of the land owners or the state, but should be spent on the development of industries, infrastructure and thereby prepare for self-sustained growth of the economy later on. Furthermore, agriculture becomes commercialized and mechanized via technological advancement; shifts increasingly towards cash or export-oriented crops; and there is a growth of agricultural entrepreneurship. The strategic factor is that investment level should be above 5% of the national income. Take-off This stage is characterized by dynamic economic growth. The main feature of this stage is rapid, self-sustained growth. Take-off occurs when sector led growth becomes common and society is driven more by economic processes than traditions. In discussing the take-off, Rostow is noted to have adopted the term transition, which

Sugata Sen

Page 1

describes the process of a traditional economy becoming a modern one. As per Rostow there are three main requirements for take-off: 1. The rate of productive investment should rise from approximately 5% to over 10% of national income or net national product. 2. The development of one or more substantial manufacturing sectors, with a high rate of growth. Drive to maturity After take-off there follows a long interval of sustained growth known as the stage of drive to maturity. Now regularly growing economy drives to extend modern technology over the whole front of its economic activity. Some 10-20% of the national income is steadily invested, permitting output regularly to outstrip the increase in population. The make-up of the economy changes unceasingly as technique improves, new industries accelerate and older industries level off. The economy finds its place in the international economy: goods formerly imported are produced at home, new import requirements develop, and new export commodities to match them. The leading sectors will in an economy be determined by the nature of resource endowments and not only by technology. The structural changes in the society during this stage are in three ways: Work force composition in the agriculture shifts from 75% of the working population to 20%. The workers acquire greater skill and their wages increase in real term. The character of leadership changes significantly in the industries and a high degree of professionalism is introduced. Environmental and health cost of industrialization is recognized and policy changes are thus made. This changes leads to reduction in poverty rate and increasing standards of living, as the society no longer needs to sacrifice its comfort in order to build up certain sectors. The age of high mass-consumption In the age of high mass-consumption the leading sectors shift towards durable consumers' goods and services. As societies achieved maturity in the twentieth century two things happened: real income per head rose to a point where a large number of persons gained a command over consumption which transcended basic food, shelter, and clothing and the structure of the working force changed in ways which increased not only the proportion of urban to total population, but also the proportion of the population working in offices or in skilled factory jobs. In addition to these economic changes, the society ceased to accept the further extension of modern technology as an overriding objective. It is in this post-maturity stage, for example, that, through the political process, Western societies have chosen to allocate increased resources to social welfare and security. Criticism of the model Rostow is mechanical in the sense that the underlying motor of change is not disclosed and therefore the stages become little more than a classificatory system based on data from developed countries. Rostow is historical in the sense that the end result is known at the outset and is derived from the historical geography of a developed, bureaucratic society. His model is based on American and European history and defines the American norm of high mass consumption as integral to the economic development process of all industrialized societies. Rostows Model does not apply to the Asian and the African countries as events in these countries are not justified in any stage of his model. Moreover the stages are not identifiable properly as the conditions of the take-off and pre take-off stage are every similar and also overlap. The most disabling assumption that Rostow has taken is of trying to fit economic progress into a linear system. This assumption is false due to empirical evidence of many countries making false starts then reaching a degree of progress and change and then slipping back. In the case of contemporary Russia slipping back from high mass consumption to a country in transition, the main cause being political change and Cold War.

Sugata Sen

Page 2

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- York Peek Style Refrigerant Level Sensor CalibrationDokument6 SeitenYork Peek Style Refrigerant Level Sensor CalibrationCharlie GaskellNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2001 - Chetty - CFD Modelling of A RapidorrDokument5 Seiten2001 - Chetty - CFD Modelling of A Rapidorrarcher178Noch keine Bewertungen

- Exercises 1 FinalDokument2 SeitenExercises 1 FinalRemalyn Quinay CasemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quad Exclusive or Gate: PD CC oDokument7 SeitenQuad Exclusive or Gate: PD CC oHungChiHoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Drainage Service GuidelinesDokument15 SeitenDrainage Service GuidelinesMarllon LobatoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1st Quarter EIM 4Dokument6 Seiten1st Quarter EIM 4Victor RosalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- のわる式証明写真メーカー|PicrewDokument1 Seiteのわる式証明写真メーカー|PicrewpapafritarancheraNoch keine Bewertungen

- SMILE System For 2d 3d DSMC ComputationDokument6 SeitenSMILE System For 2d 3d DSMC ComputationchanmyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- QAV - 1.1. Report (Sup1)Dokument2 SeitenQAV - 1.1. Report (Sup1)Rohit SoniNoch keine Bewertungen

- GeothermalenergyDokument2 SeitenGeothermalenergyapi-238213314Noch keine Bewertungen

- ASTM 6365 - 99 - Spark TestDokument4 SeitenASTM 6365 - 99 - Spark Testjudith_ayala_10Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ford Transsit... 2.4 Wwiring DiagramDokument3 SeitenFord Transsit... 2.4 Wwiring DiagramTuan TranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bohol HRMD Plan 2011-2015Dokument233 SeitenBohol HRMD Plan 2011-2015Don Vincent Bautista Busto100% (1)

- MHC-S9D AmplificadorDokument28 SeitenMHC-S9D AmplificadorEnyah RodriguezNoch keine Bewertungen

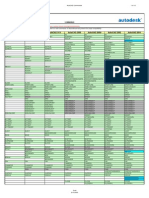

- Autocad R12 Autocad R13 Autocad R14 Autocad 2000 Autocad 2000I Autocad 2002 Autocad 2004Dokument12 SeitenAutocad R12 Autocad R13 Autocad R14 Autocad 2000 Autocad 2000I Autocad 2002 Autocad 2004veteranul13Noch keine Bewertungen

- IA-NT-PWR-2.4-Reference GuideDokument110 SeitenIA-NT-PWR-2.4-Reference GuideSamuel LeiteNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Basics of Business Management Vol I PDFDokument284 SeitenThe Basics of Business Management Vol I PDFKnjaz Milos100% (1)

- Application Form For Technical Position: Central Institute of Plastics Engineering & Technology (Cipet)Dokument8 SeitenApplication Form For Technical Position: Central Institute of Plastics Engineering & Technology (Cipet)dev123Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2009-07-04 170949 Mazda TimingDokument8 Seiten2009-07-04 170949 Mazda TimingSuksan SananmuangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rules For Building and Classing Marine Vessels 2022 - Part 5C, Specific Vessel Types (Chapters 1-6)Dokument1.087 SeitenRules For Building and Classing Marine Vessels 2022 - Part 5C, Specific Vessel Types (Chapters 1-6)Muhammad Rifqi ZulfahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- York Ylcs 725 HaDokument52 SeitenYork Ylcs 725 HaDalila Ammar100% (2)

- Oil Checks On Linde Reach Stacker Heavy TrucksDokument2 SeitenOil Checks On Linde Reach Stacker Heavy TrucksmliugongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Light Runner BrochureDokument4 SeitenLight Runner Brochureguruprasad19852011Noch keine Bewertungen

- Character SheetDokument2 SeitenCharacter SheetBen DennyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Multi Class Coding SystemDokument20 SeitenMulti Class Coding SystemDaniel LoretoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Digital Marketing Course India SyllabusDokument34 SeitenDigital Marketing Course India SyllabusAmit KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- K9900 Series Level GaugeDokument2 SeitenK9900 Series Level GaugeBilly Isea DenaroNoch keine Bewertungen

- 90-Day Performance ReviewDokument2 Seiten90-Day Performance ReviewKhan Mohammad Mahmud HasanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Workbook Answer Key Unit 9 Useful Stuff - 59cc01951723dd7c77f5bac7 PDFDokument2 SeitenWorkbook Answer Key Unit 9 Useful Stuff - 59cc01951723dd7c77f5bac7 PDFarielveron50% (2)

- 2005 TJ BodyDokument214 Seiten2005 TJ BodyArt Doe100% (1)