Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Political Myanmar

Hochgeladen von

Atma DewitaOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Political Myanmar

Hochgeladen von

Atma DewitaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Political Transition in Myanmar: A New Model for Democratization Author(s): ASHLEY SOUTH Reviewed work(s): Source: Contemporary Southeast

Asia, Vol. 26, No. 2 (August 2004), pp. 233-255 Published by: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS) Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25798687 . Accessed: 09/11/2012 04:25

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS) is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Contemporary Southeast Asia.

http://www.jstor.org

Contemporary Southeast Asia 26, no. 2 (2004): 233-55

ISSN 0219-797X

in Transition A New Model Myanmar: for Democratization Political

ASHLEY SOUTH

examines and political in transition This article social (Burma), arguing that the tentative re-emergence of Myanmar civil society networks within and between ethnic nationality/ is one of the most minority communities over the past decade ? but under-examined ? aspects of the social and significant situation in the country. This article analyses the political the country's ethnic nationalist leaders and challenges facing It also addresses communities. the roles that foreign aid can Myanmar, play in supporting the re-emergence of civil society in a policy of selective or targeted engagement. and advocates

Introduction to the contrary, the outlook for political transition Despite appearances in Myanmar is not entirely bleak. However, observers and activists must consider a broader range of strategies for democratization.

the government's to democracy. country, including "road-map" the openings for change that have emerged are quite limited. However, the oppositions' lack of leverage, and the ineffectiveness of Given the military junta will probably continue to determine the sanctions, course of events. Opposition to the groups have generally responded in one of two ways: democratization initiatives either by regime's manoeuvre within government-controlled forums seeking some room for as the current National Convention), or by boycotting these ? (such

of The past year has seen a flurry political activity in and on the

reinforcinga polarization ofMyanmar politics which began in the

233

234

Ashley South

1960s, and has served the entrenched military government better than it has the increasingly marginalized forces. opposition have focused on elite-level regime change, and groups Opposition the need to install a more accountable Such government in Yangon. are based on an assumption which is shared by themilitary approaches transition in Myanmar must come from the top, regime: that political that is, directed by the central government. (Even in a best-case scenario, the government-controlled level transition.) National Convention will only concern elite

to any process of sustained democratization. While change at the national level, whether revolutionary or gradual, is urgently required, sustained if accompanied transition can only be achieved democratic by local participation.

This notion ignorestherole of civil society, which will be essential

fornational-level transition, re-emergent civil society networks represent an important vehicle for long-term, "bottom-up" democratization in areas. Furthermore, in ethnic nationality civil Myanmar, especially society actors often have access to conflict-affected areas which are out can implement to international Local NGOs of-bounds agencies. and humanitarian community development projects in border areas, in and human capital. ways which build local capacities activists) (particularly overseas-based Although Myanmar-watchers often assume that there is no civil society in the country, this far from true. The tentative re-emergence of civil society networks within and ethnic nationality communities has been one of the most between ? ? but under-examined aspects of the social and political significant over the past decade. in Myanmar situation Efforts to build local are already underway in government-controlled areas, in democracy some ethnic nationality-populated ceasefire and war zones, and in countries. Although these local initiatives will not bring neighbouring about national-level change in themselves, any centrally-directed reforms are unlikely to succeed unless accompanied or even preceded by such grassroots participation. This article argues that a combination of "top-down" and "bottom are necessary, but that neither is up" strategies for democratization the strategic challenges sufficient. It examines leaders facing political and communities, and particularly the ethnic nationalities, who constitute

with only limitedoptions available In thecurrent political climate,

thatforeign can play in supportingthere-emergence civil society aid of

inMyanmar. international

30-40

per cent of the population.

It also addresses

the role

The promotion of civil society in Myanmar should be a priorityfor

donors. Rather than sitting on the sidelines while the

Political Transition inMyanmar situation goes from bad to worse, the international community

235 (the

in a constructive, In this case, if selective, manner. with Myanmar humanitarian and development aid are not substitutes for political intervention ? but a way into political action. Of course, humanitarian

United States, European Union and United Nations) should engage

principles demand thataid be given impartially,and not to further political agendas. Nevertheless, all aid has political impact,which

should be properly calculated. otherwise indicated, data comes from the author's research inMyanmar, Thailand and China, conducted between 2001-04. Unless Politics and the National Convention assume ? even hope ? that a

Elite-level

Few would deny theurgent need forchange in Myanmar butwhat kind

of transition, and how? come abruptly. However, most key players expect a more gradual and advocate for a negotiated process realignment, with less bloodshed, of democratization. and draw on the experience Many are pessimistic, regime reform,without any appreciable degree of power-sharing

repeat of the 1988 democracyuprising is likely,and thatchange will

Some

activists

of other countries in the region to suggest that the best hope is for with the opposition. Although the tactics adopted by stakeholders in

these different scenarios may vary, many the same. There are three potential parties strategic considerations remain to political transition inMyanmar: gradual

and dialogue with the SPDC. However, Daw necessity for compromise San Suu Kyi's efforts to mobilize her supporters and test the Aung limits of the generals' tolerance came to a bloody end on 30 May 2004, mob ambushed her motorcade, when a government-organized killing and injuring dozens of her supporters. With "the lady" in detention, efforts to foster dialogue between the SPDC and NLD international came to a halt. Since its refusal to recognize the results of the May 1990 general election, themilitary government has resisted all options but a managed or "guided" transition to some type of "disciplined" (by the military) the military) democracy. On 30 August 2003, Myanmar's newly (by

urban-based led by Daw Aung San Su Kyi's democracy movement for Democracy National (NLD), and various ethnic nationality League the NLD and most democracy groups in exile have parties. While demanded of the 1990 election results as a consistently recognition basis for a political settlement, they have mostly come to accept the

the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC)military regime, the

appointed prime minister (andMilitary Intelligence chief), General

236

Ashley South

Khin Nyunt, announced the resumptionof a National Convention (NC)

to draft a new democracy".1 control

was clearly positioning itself to in 1996). The military government

a transitional process, the success and legitimacy of which

to "road map part of a seven-stage in 1993, and suspended (The original NC was convened constitution

Endorsed NC, underwhat conditions. depends onwho participates in the China, ASEAN and theUN SecretaryGeneral's Special Envoy for by

Myanmar, Razali the only became Ismail, Khin Nyunt's "road-map" in town, at least at the national/elite level. political game of the prospects after much plotting and brinkmanship, However, NC producing the government-controlled significant change currently seem quite limited. Three days before the NC re-opened, on 14 May that they announced failed to reassure the

two main 2004, Myanmar's opposition parties would not join the convention. The government

NLD and die United Nationalities Alliance (UNA? a coalition of ethnic nationality parties), that itwould permit genuine debate over

key issues. Although UNA do not appear in Myanmar politics these concerns were well-founded, the NLD and to have a realistic B" ? and elite-level "plan is once again deadlocked, with the government

over one hundred they include by the government, picked from armed ethnic nationality have groups, which representatives in the absence of the NLD and ceasefires with Yangon. Nevertheless, In effect, hardliners within UNA, the NC process is far from inclusive. the regime, at the expense and abroad. Myanmar appear of its perceived legitimacy both within

holdingmost of thekey cards. Although most of the 1,076 delegates to theNC have been hand

the SPDC have ensured that the convention is tightly controlled by With both theSPDC and NLD stickingto their might principles, it

to some observers that the urban-based (predominantly Burman) to Myanmar's elites are not really trying to find solutions political SPDC or NLD, the ceasefire groups have at protracted crises. Unlike and use this historic opportunity least attempted tomake the NC work ? to raise some of the issues which concern them, for the first time since

independence. The stakes are high, and some analysts suggest that Khin Nyunt (the "good cop") has been set-up to fail while protecting Senior General Than Shwe to (the "bad cop" and junta chairman) from the need place reform. However, Khin Nyunt is clever in history and therefore motivated increasingly personalized and ambitious, mindful of his tomake his road-map work.2 of resources

from the Union Solidarity and DevelopmentAssociation military to the

Shwe's

In this, may gain some supportfromarmyofficers he who oppose Than

style of rule, and diversion

Political Transition inMyanmar

237

? a mass movement established in (USDA September 1993 under the SPDC Chairman's patronage).Nevertheless,Than Shwe still calls the within theNC. The third set of political actors inMyanmar had been largely halt followingthebrutal eventsof 30May. The 1994 and all subsequent UN General Assembly resolutionsregarding Myanmar have called fora

Many ethnic nationality cadres are wary of the NLD leadership, is largely composed which of ex-Myanmar Army officers, who share a common political culture and conceptions of state-society relations based on a strong, centralized state. However, most ethnic leaders have negotiations which may come out of bipartite talks in Yangon. This was sidelined within the UN-brokered "peace process", which came to a shots, and has seemingly suppressed open discussion of key issues

NLD (and otherparties elected in 1990), and the ethnicnationalities.

tripartite solution

to the country's problems,

involving

the government,

trustedDaw Aung San Suu Kyi to demand their inclusion in any

options: either be co-opted into endorsing an agreement which they had little part in negotiating, or insist on convening a possibly lengthy In the context of any pre inter-nationalities consultation process.3 to accusations the ethnic nationalities of obstructing national exposed reconciliation. Either scenario would suit the "divide and rule" strategy of elements in Burman political society.

and NLD, the process would have gained considerable momentum before ethnic nationality representatives were brought into the picture. In this case, the latter risked further marginalization, faced with two

a risky strategy: an agreement if had been reached between the SPDC

existingdeal between theNLD and SPDC, such a demand might have

Opportunities and Challenges

a half-century of mostly civil war, ethnic low-intensity are mired areas of Myanmar in a humanitarian minority-populated are especially crisis. Needs acute in food and livelihoods security, Following

might play inbreaking thepolitical deadlock, and beginning to address

the urgent

and health, and civilian protection.4 education of expanded in the National The possibility participation Convention created an opportunity to re-present the importance of the in Myanmar, "ethnic question" and the roles the ethnic nationalities

on this limited situation. To capitalize humanitarian the different ethnic nationalist blocs would have to agree opportunity, on basic strategy, and develop common positions on the main issues to be included in tripartite negotiations. The ethnic nationalist community is composed of three elements:

238

Ashley South

2. Some

1. The United Nationalities Alliance (UNA), representingsixty-five ethnic nationality candidates elected in 1990, which has always worked closelywith theNLD;

twenty armed ceasefires with Yangon still control extensive ethnic have which organizations agreed since 1989, retain their arms, and sometimes the government, most have territories; still at war with several members

3. Those

which are members of theNational Democratic Front (theNDF,

established in 1976, agreements).5 significantly

insurgent groups

of

symbolically important, theirmilitary strength has declined

in recent years.

Although

the

insurgents

of which remain

politically

ceasefire and

The challenge facing Myanmar's ethnic nationality leaders is how to

and within these different between engineer a degree of coherence or naive and sectors. In doing so they risk being exposed as divided ? over key issues, and once again consigned to a marginal unrealistic ? over the future of the country are made by the role as crucial decisions political elite.

urban

The Ceasefire The

Movement:

1989-2004

crises. recent political much science literature has focused on Although for insurgency, Myanmar's the "opportunity motives" rebellions have been driven by a mixture of genuine grievances and political long in recent years, a Nevertheless, military-economic opportunism. relatively stable border areas. Until 1989, "peace-making" environment has emerged in many

are and political failure in Myanmar history of insurgency Since in 1948, and especially interlinked. closely independence ofMyanmar's following the military takeover of 1962, representatives have ethnic nationalities been excluded from meaningful in national politics. Historically, the "ethnic question" participation has been at the heart of Myanmar's social and protracted political, humanitarian

and rule" strategy, under which front, such as the NDF. To

the Myanmar Army had been fighting two inter ? one against the ethnic nationalist connected civil wars insurgents and another against the Communist the (CPB). With Party of Burma of the latter in early 1989, Yangon could concentrate its forces collapse ethnic rebels. The junta devised a classic "divide against the beleaguered

individual insurgent while refusingtonegotiatewith any joint groups,

the consternation of the embattled ethnic

ceasefire

agreements were

struck with

Political Transition inMyanmar allies on

239

the Thailand-Myanmar 1989-95 ceasefire border, between were made with a total of fifteen insurgent organizations, arrangements and Kachin NDF member-groups.6 Shan, Pa-O, Palaung including the ceasefire process can be sustained, and move Whether from the current "negative peace" ? characterized the relative absence of by onto a positive, "peace-building" will be fundamental violence ? phase, to the success of reconstruction and national reconciliation efforts. The nature of the ceasefire agreements are not uniform, although in all cases the ex-insurgents have retained their arms, and still control situation on

the military However, regime and insurgent hierarchies. they also to work towards the rehabilitation of deeply represent opportunities troubled communities. ceasefires do not guarantee sustainable and However, peace of civilian populations have occurred development. Major displacements after ceasefires were agreed between the government and armed ethnic

are not peace the ground). The ceasefires treaties, and lack all but the most rudimentary accommodation of the ex generally In some quarters, and developmental demands. insurgents' political as benefiting vested interests in these agreements have been dismissed

sometimes extensiveblocks of territory recognitionof themilitary (in

groups inKachin (1994) andMon (1995) States. Although armedconflict

came to an end in these areas, families and induced displacement as a communities continue to lose their land and become displaced, result of increased natural resource extraction (logging, and jade and and infrastructure development. Another cause of post gold mining) ceasefire displacement is increased militarization (despite the cessation of armed conflict) and theMyanmar Army's expansion into previously contested areas.

The KNU Ceasefire

potentially significant development inMyanmar, agreed a ceasefire with

when theKaren National Union (KNU), the last group major insurgent

of dogged resistance to the Myanmar military (the KNU went in 1949) has given the Karen ethno-nationalist movement underground a special symbolic weight inMyanmar politics. IfKaren leaders in exile can grasp themoment, theymay be able to engage and inside Myanmar years the urgent needs of Karen society.

occurred

in December

2003,

are thedetails of thisarrangement stillbeingworked out.The KNU's 55

themilitary government ?

although

with theregime from"withinthe legalfold", while addressing politically It is however, an open secret thattheKNU is being pushed by the

government into a hasty agreement with Yangon. Understandably,

Thailand wants tobe rid of the 150,000 (mostly Karen) refugeesin the

Thai

240 kingdom, and is keen to exploit the economic opportunities

Ashley South that peace

may bring to its borders.However, Thai pressure risks splitting the

KNU wreck into pro- and anti-ceasefire (and -NC) factions, and could yet the fragile truce. Thailand's long-term interests would be better the Karen to proceed at their own pace. served by allowing The apparent end to armed conflict in Karen State comes as

organizations increasing numbers of international non-governmental International agencies may, for the first time (INGOs) enter Myanmar. to address the opportunity the deep-seated have in decades, in border areas ? and development humanitarian if they problems address work in partnership with local civil society, in ways which some of the route causes of the armed conflict. KNU have the government, In their talks with negotiators emphasized (IDPs) be

displaced people suggested thattheplightofup to a million internally

addressed, before any refugee repatriation is undertaken.

the extent of the displacement

crisis

in Myanmar,

and

Most aid workers agree that the time is not yet righttobegin sending of the ongoing problems experienced by conflict-affected populations

refugees back from Thailand. Any attempts to assist displaced Karen villagers musf take account

The protection in other parts of Myanmar. of civilians must be a At a minimum, clearance should proceed any major landmine priority. resettlement initiative. Quite properly, UNHCR has discussed refugee repatriation options with the Thai authorities, and with theMyanmar government. However,

crucial aspects ofUN (and INGO) access to proposed IDP and refugee

zones have yet to be agreed. repatriation-resettlement InMarch 2004 UNHCR that it had negotiated access to announced return areas in eastern Myanmar. With funding of about US$1 refugee

education and de-mining. Under its arrangement with the government, the UN refugee agency has gained access to seven of the eleven townships in Myanmar (Tenasserim Division, Mon State and Karen State) from themajority of refugees in Thailand i.e. for the first which have fled ? UNHCR will have access to Thailand border areas via Yangon. time, Having visited several of these areas, inmid-2004, UNHCR was making to upgrade infrastructure in areas of possible refugee initial preparations are reportedly to be health and education return; programmes

million for2004, UNHCR will support projects in communityhealth

Myanmar Red Cross (heavily infiltrated implemented throughthe by and the Military Intelligence) Myanmar Maternal and Child Welfare Association (led by General Khin Nyunt's wife).7 Unlike along theThailand side of theborder,where ithas three UNHCR is apparentlynot going to open offices in return field offices,

Political Transition inMyanmar areas (e.g. the Karen State capital, a protective Pa'an). The UN will be present

241 by

will notbe operationalon theground,andwill not therefore proxy only,

be unable to provide Politics are the positions of (KIO) Organisation presence.

Inter-ethnic UNA

There is a fairly high degree of coherence between thepolicies of the

parties and the rump NDF.8 More problematic various ceasefire groups. The Kachin Independence

six politically engaged ceasefire groups, most of which are ex-NDF members. The NMSP in particular plays an important role, with a foot of the ceasefire groups to the rump NDF, and also enjoys good relations

and New Mon State Party (NMSP) have taken the lead among a group in all three camps of theethnicnationalitycommunity:it is the closest

with theUNA leadership.

may feel thatthereismore tobe gained by followingtheSPDC line, and

staying clear of politics, in order to concentrate on local community and economic development programmes (including, in some cases, the drugs trade). Some observers have expected the SPDC to offer further to individual ceasefire groups, in exchange for their support concessions in efforts to complete theNational Convention. (or at least, acquiescence)

in the positions of a number of ex-CPB and other militias However, northern Myanmar have been less clear. Wa, Kokang and PaO leaders

of the proposed constitution, agreed between 1993-96.9 Despite themilitary government's longstanding policies of "divide in mid-2004 and rule" vis-i-vis the ethnic nationalities, they seemed more united that at any time in recent years. However, itwas still far from unclear whether their concerns would be addressed by the NC. Indeed, on 11May the ceasefire groups were informed that their demands not be met by the government. would It seemed therefore that the National Convention would not be open to genuine political debate or social comment. The issue of federalism illustrates the gulf between the government to and ethnic nationality this is anathema representatives. Although are most ethnic nationality parties inMyanmar the generals in Yangon, committed in principle to a federal solution to constitutional Myanmar's crisis. However, and "federating" there are different "federalizing" processes, various kinds of relation between the states and union, and

other northern Shan State ceasefire groups have adopted positions ? similar to the KIO-NMSP i.e. that the "sixth objective" of the camp in the future state" is NC, which guarantees "military participation are necessary to some of the 104 and that amendments unacceptable, articles

However, since late 2003 theUnitedWa StateArmy (UWSA) and

242

Ashley South

different types of federal structure. In recent years, ethnic nationality and pan-Myanmar groups in exile have begun to discuss democracy in detail, paying special attention the situation of such arrangements minorities within and other states, e.g., the Wa ethnically-defined in Shan State. minorities

The Limits of a Top-Down Approach

Given

policies ofASEAN and China, and the limited impact ofUS, UN and EU fulminationsagainst the SPDC, it is difficultto see how pressure can be brought to bear on Yangon, beyond indirect support for the ?

and the opposition "progressive" Khin Nyunt faction. Furthermore, in particular ? have limited leverage vis-a-vis the ethnic nationalities it its past record and recent pronouncements, the government. Given

the competing/complementary

"constructive

engagement"

or even sensitive areas like human as federalism and power-sharing, and group rights. it is for a moment at the level of inter-elite negotiations, Remaining ? event of continued deadlock ? in the worth considering whether to facilitate issues could be used social welfare and humanitarian and eventually social and political transition. In processes of dialogue, addressing subjects like displacement (refugees and IDPs), education or into needs be brought planning, might analysis, or evaluation and monitoring activities, which could implementation to foster models in the of collaboration. be used Cooperation sector might into humanitarian later be expanded, and developed of state-society and centre broader, more explicitly political discussions periphery relations. A focus on IDPs in particular, would help to ensure in such processes, as most of ethnic nationality participation Myanmar's two million-plus displaced people are from ethnic minoritycommunities. stakeholders dialogue For humanitarian issues and peace-building

is therefore quite likely thattheSPDC will refuse todiscuss issues such

HIV/AIDS in the first stage of any "confidence building" process,

well

below" approaches may be considered in their own right, as valuable as being an alternative means to gradual democratization.

to become for transformative vehicles would careful preparation, require consultation with affected communities, and local and including international agencies. This is one example of how elite-level blueprint ? ? on a policy of "coherence" can be based style approaches more participatory involve and by complemented approaches, which a wider lack of the government's empower range of actors. Given incentive to engage in dialogue, civil society-based from "development

Political Transition inMyanmar Civil Society: a Vehicle for Democratization

243

and social welfare (CBOs), media organizations community-based as well as religious and cultural groups (traditional and organizations, and more overtly political organizations. However, modern), political to assume state power are not part of civil society ? parties seeking

between the state and thefamily. These include a broad range of

and denotes voluntary associations

In this article, the term"civil society" is derived fromde Tocqueville,

and networks which are intermediate

are essential for sustained, civil society networks Functioning and for conflict social and political transition inMyanmar, bottom-up resolution at both the national and local levels. It is essential that the social and ethnic communities country's diverse enjoy a sense of in any transitional process, and equip themselves to fill the ownership that may emerge, either as a result of abrupt shifts in power vacuum national politics, or of a more gradual withdrawal of the military from control state and local power. The ability of people to organize, and reassume over aspects of their lives which since the 1960s have been such grassroots mobilization.

may promote or inhibit itsdevelopment. although they

will depend on armies), military (including insurgent abrogatedby the

and civil society networks are necessary, Popular participation comes suddenly, or ismore incremental. whether change inMyanmar in Burma ? like Indeed, the failure of the 1988 "Democracy Uprising" ? can in part be attributed that of the 1989 "Democracy Spring" in China to the suppression of civil society under authoritarian rule. A lack of sustained change. Unlike those in Eastern Europe in the late 1980s, the

from initiating democraticculturepreventedpowerfulpolitical gestures

Philippines in 1986 and Thailand in 1992, theBurmese and Chinese

movements. in denying social groups a The regime had succeeded or the economy, except under strict foothold in mainstream politics state control. Potential opposition was thereby marginalized, and could the military in times of crisis and upheaval, emerge only presenting on "anarchy" and "chaos" (thus the State with a pretext to clampdown Law and Order Restoration Council, SLORC). their task as the Myanmar Army ideologues have long viewed defence of a centralized, unitary state, which emerged from the struggle for independence. The military has sought to impose a model of state

which played importantroles in the Polish and Filipino democracy

democracy activists had little social space within which to operate, or to build upon the people's evident desire for fundamental change. In and China had no counterpart to the trades unions particular, Myanmar

society relations, in which the (ethnic minority) periphery was

244 dominated

Ashley South

centre. As pluralism was by a strong (Burman-orientated) itwas with a state-sponsored nationalism. The replaced suppressed, saw diverse (and according to themilitary, of "Burmanization" process subsumed under divisive) minority cultures, histories and aspirations a homogenizing derived from the Burman historical "national" identity, tradition. In the 1960s, as the state extended autonomous of social life, civil aspects its control society over previously could no

or forced into open revolt. The driven underground, eliminated, to the military government renewed existence of armed opposition a pretext for the further extension of state control, and provided to the of diverse social groups deemed suppression antipathetic modernizing perhaps,

longer operate independently.Opposition to the regimewas either

networks

According toDavid Steinberg,"civil society died under theBSPP;

more accurately, itwas murdered".10 The 1974 constitution

state-socialist

project.

outlawed all political activitybeyond the strictcontrol of effectively

the state. Particularly hard hit were trade unions and most professional other aspects of civil associations (e.g., journalists' groups). However, society survived, albeit in a dormant form. Since 1988, state-society relations have been further centralized, and social control reinforced by the indoctrination of civil servants, reformation of local militias, and creation of new mass organizations

and of expression severely restricted, as have freedoms to information and access and independent media. elements of civil society have survived, and are beginning Nevertheless, has been association,

to re-emerge.

such as the USDA. Beyond this highly circumscribed sector, the operation of independent political parties, such as theNLD and UNA,

Civil

Society Actors

inMyanmar

Extensive capital, as well country).

civil society networks, building on local capacities and social exist in and between the ceasefire and war zones ofMyanmar, as in areas under government control (the majority of the

Zones ofOngoing Armed Conflict

Although, especially since

reflected in their practices. Many aspects of life in the "liberated zones" have been characterized by a top-down tributary political system, aspects

to be fighting for democracy inMyanmar, this ideal is not always

1988, most

insurgent groups have

claimed

Political Transition inMyanmar of which Insurgent opinions, militarized

245

insurgentsin the 1980s and '90s, the rebel armies declined inmilitary ? and thus ? political significance. Ironicallythough, thedecline of theold insurgent paradigm opened thespace forthe emergenceofnew

participatory forms of social and political organization among In the 1990s a number of ethnic nationality communities. opposition local NGOs were organized by Chin, Kachin, Shan, Lahu, Karenni, student and youth, women's, Karen, Tavoyan, Mon and all-Myanmar and human rights groups in the border areas. These environmental ofmainstream and more

patrons, China

hierarchies have often been suppressed. in recent years, civil society networks have begun to However, areas. As in non-government their ex-cold war controlled expand and Thailand, withdrew support from Myanmar*s ethnic

recall precolonial forms of socio-political organization. the expression of diverse leaders have tended to discourage initiatives beyond the direct control of and socio-political

armed groups. Representing new models of organization, these networks constituted one of the most dynamic in an aspects scene. As a result of their activities, otherwise bleak political those in the struggle for ethnic rights and self-determination in engaged have been obliged to acknowledge the importance ofwomen's Myanmar and democratic practices ? not rights, community-level participation as distant goals, but as ongoing processes. Since the 1990s, the just have been challenged to NMSP, KNU and other armed organizations reassess their records, and examine the degree towhich their strategies reflected these ideals. In a parallel development, the refugee and other relief and welfare along the Thai border also grew in interesting ways. Like and youth wings associated with most insurgent groups, and Mon the Karen, Karenni refugee committees were originally factions within the insurgent hierarchy. As the controlled by dominant latter lost ground throughout the 1990s, the number of refugees in Thailand grew annually, and assumed a new importance as a civilian organizations the women's

began to occupy thepolitical space createdby thedeclining influence

and development towork cross-border, with continued groups which communities inside Myanmar. Since the early 1990s, Karen displaced ? teams have provided and later Chin, Shan, Karenni and Mon ? relief (food and medicines) and undertaken humanitarian community

support base, source of recruits and safe haven for the armed groups. as the refugee situation along Thailand border was gradually However, ? and since 1998, internationalized, with the presence ofmore INGOs ? to become more UNHCR the refugee committees were obliged to (if not more representative of) their clients, the refugees. responsive A particularly dynamic sub-sector was composed of local relief

246 development and educational work among displaced

Ashley South communities, in

what had once been the "liberated zones" (behind the frontlinesof

war),

Education (KED). In many areas, these schools consist of Department little more than a few bamboo benches under the trees, which must move repeatedly, as villagers are displaced by the ongoing armed conflict.

insideMyanmar, most of which are loosely supervised by theKNU

but were now mostly zones of ongoing armed conflict. For example, there is a network of some 400 Karen village

schools

In the face of such difficulties, many IDP communities attempt to their children with some form of continuity,and a basic provide

uneasy partnership with local teachers and the KED attempts to standardize the curriculum self-help organizations, within this massively under-funded and examinations system, which education. In a sometimes

models

IDP assistance groups organizations, of their "parent" insurgent have developed relatively independently they still rely on the latter for security, and although organizations share most of the same broad ethno-nationalist goals. In demonstrating to donors and beneficiaries (their local transparency and accountability these civil society networks have emerged as important communities), Like refugee-based of social mobilization.

with schools in the refugeecamps. still enjoys close links

the new

exist among ethnic nationality communities civil society networks "inside" Myanmar. These include Christian and Buddhist organizations, as and many traditional village associations (e.g., funeral societies), well as more formally-established CBOs and local NGOs literature (e.g. and business and culture associations support groups). The tentative re-emergence of civil society networks among and in Myanmar is a complex phenomenon, between local communities owing much to the political space created by the ceasefire process since 1989. Other factors in the realignment of state-society relations during this period include the increased presence of INGOs inMyanmar, and in the early 1990s. the partial opening of the economy in many ceasefire and adjacent areas continue to have Villagers

a Although the stategenerally inhibits theirformation, varietyof local

Ceasefire

and Government-Controlled

Areas

most

of the ex-insurgents' political rudimentary accommodation demands. ethnic nationalist cadres Furthermore, developmental

their rights abused by theMyanmar Army (and local militias). However, the ceasefire process has generally resulted in a decrease in the most extreme and arbitrary types of violence associated with the armed for travel and trade. conflict, while increasing opportunities The ceasefires are not peace treaties, and generally lack all but the and are

Political Transition inMyanmar generally more familiar with As the top-down approaches used

247 inmilitary

and political campaigns, than with bottom-up development and conflict

resolution methods. elsewhere in the country, local initiatives are

practices, and a lack of strategic planning and implementation capacities. for the the ceasefires have created some opportunities Nevertheless, of war-torn communities. reconstruction ? are mixed. Over the Patterns of development ? and stagnation ten years, extensive community networks within the clan-based past Kachin society have re-emerged in the space created by the relatively further to the South, since the stable Kachin ceasefires. Meanwhile, has in extending its community income development, and adult literacy activities beyond the NMSP-controlled generation across lower Myanmar. zones, toMon communities succeeded education

frequently undermined by poor governance, parallel exploitative

1995 NMSP-SLORC ceasefire,the Mon Women's Organisation (MWO)

and health systems, which rely on community and donor some serious setbacks, during the 2002-03 school support. Despite to run 187 Mon National the party managed Schools and 186 year "mixed" schools (shared with the state system), attended by more than 50,000 pupils, 70 per cent ofwhom live in government-controlled this is a para-state Department, a civil society initiative.) or local authority

Like the KIO and otherarmedethnicgroups, the NMSP administers

areas. (Strictly NMSP Education speaking,as it is implementedby the

system, rather than

alternative community education approaches. groups have pioneered For example, in 2003 about 55,000 school students attended Summer across Mon and Buddhist Literature lower Trainings Teachings

Myanmar.11

political and military "space" within which civil society may re-emerge, of the key players over the past decade have often been members religious and social welfare networks. Many of these were established in the 1950s, only to be suppressed after 1962. In recent years, the Chin, Karen, Mon, PaO, Shan and other Literature and Culture Committees have been among the few specifically ethnic organizations tolerated by the government. As the state education such system has deteriorated,

NMSP and otherceasefiregroupshave provided the Although the

or for such local initiatives is usually welfarerather than explicitly political. Whatever their development-oriented, are individual from below" the initiators of "development views, or community workers. primarily religious The motivation to register far, few indigenous NGOs have been allowed with the authorities. The two most well-known were established legally after the KIO ceasefire. The Shalom Foundation was founded in 2001 Thus

248

Ashley South

by theReverend Saboi Jum,a key figure in the ceasefire process. It

on mediation 12 full-time staff, and works and conflict employs resolution issues, building capacity in these key sectors. in 1998, and Foundation was established The Metta Development

by 2003 had a budget of over US$500,000, and 13 full-time staff. Although its importanceto thebroader scale of development initiatives

as a in Myanmar should not be overestimated, Metta is often viewed success story, which other fledgling local NGOs might emulate. Metta has projects in Shan, Karenni, Karen and Mon States, and the Irrawaddy

methods, leading to the creation of Delta, which employ participatory

CBOs, and action plans and project proposals. Metta also implements income generation projects, health worker training, water and sanitation schemes. projects, and a number of successful rural development that: However, Metta Director Daw Seng Raw, has complained many ethnic groups feel extremely disappointed that in general foreign governments are not responding to the progress of these ceasefire or indeed even understand their significance or context. Rather, it seems that certain sectors of the international community have the fixed idea that none of the country's deep problems, including ethnic minority issues, can be addressed until there is an over-arching political solution based upon developments in Rangoon. In contrast, the ceasefire groups believe ... that simply concentrating on the political stalemate in Rangoon and waiting for political settlements to come about ... is simply not sufficient to bring about the scale of changes that are needed.12 are not countrywide like Metta and Shalom New organizations institutions or membership groups, but often act as facilitators and innovators for longer-established In many cases these are associations. bodies ? controlled social among the few non-government religious to exist inMyanmar. institutions allowed

are often in Myanmar emergent civil society networks Although associated with Christianity, many Buddhist exist too. associations Many senior monks may have been co-opted by themilitary regime, but the sangha still has great potential as a catalyst in civil and political affairs. However, Buddhist and other traditional networks tend to be

The Anglican, and other churches in Myanmar Baptist, Catholic have well over two million members. Although most of their activities are religious-pastoral, the churches devote considerable energy and some international resources social funds) to education, (including and community welfare in armed development projects, including conflict-affected areas. However, skills and they also face considerable constraints. capacity

Political Transition inMyanmar

249

localized, and centred on individual monks, who may not conceptualize or present their aims in a manner readily intelligible towestern agencies. are therefore often "invisible" to western Such non-formal approaches (and western-trained) staff.

Foreign Aid and Civil Society

crisis in publicly expressed their concern over the "silent humanitarian themaking", is a moral and ethical that "assistance toMyanmar stating necessity." They further noted that "strengthening human capital, leadership capacity, and encouraging a more dynamic civil developing to laying the foundations for democratic contribute society will

processes".13

In June 2001 the heads ofmission of eightUN agencies in Yangon

of partnership with affected communities,and generally tryto elicit

to create the space such doctrines have helped border in particular, for more responsive and participatory to community organizations communities. However, INGOs along the border emerge among refugee in senior decision-making and rarely employ local people positions, their programmes sometimes inadvertently undermine local initiatives and health projects draw (e.g., INGO-funded refugee camp education local teachers and medics from under-resourced away indigenous and school

International

humanitarian

agencies

have

developed

a language

sector in the SPHERE Project, initiated in 1997). On the Thailand

local participation

in their programmes

(as codified

for the emergency

systems).14 a number of Myanmar-specific NGOs and donors Meanwhile, have been rather uncritical in sustaining organizations and individuals within theMyanmar opposition. Foreign aid has sometimes supported elements within ethnic nationality and democracy groups, without to the communities the degree to these are accountable considering they claim to represent. International agencies based in Yangon also have a mixed record activities in Myanmar

health

have been restricted to "programmes having grass-roots-level impact in a sustainable manner".15 This mandate, which is highly unusual to limit the agency's is designed for the UN, with the government. The UNDP Human engagement Development Initiative works "particularly in the areas of primary health care, the and food security". environment, HIV/AIDS, training and education, Now in its fourth phase, funding for the initiative has been halved, in due to scepticism over the agency's ability to implement the kind part of locally-owned programmes required.

in their relationshipwith civil society groups. Since 1993, UNDP

250

Ashley South

other

Unlike most UN agencies, the UN Office forDrugs and Crime with (UNODC) engages directlywith ceasefire groups. In partnership the governmentand UWSA, theUNODC has built schools, dams and

facilities in sub-state, and has had some success areas. in Kokang cultivation and UWSA-controlled opium "community development according to a recent assessment, ... sometimes conflicted with the (Wa) Authority top-down ... the to involve the villagers When efforts were made in the Wa

reducing However, concepts approach.

UWSA calls formore infrastructuxe and agricultural assistance, efforts to promote community development and the emergence of CBOs have the UN has recently negotiated an been largely unsuccessful. However, agreement with theUWSA, under which cornmunity-based development methods will be tolerated by theWa authorities. area where Another the UN may address humanitarian needs,

Authority felt threatened".16 Although theUNODC has responded to

while developing the roles and capacities of local civil society, isHIV/

AIDS programming. inMyanmar International agencies have access to a US$35m as part of a coordinated HIV/AIDS fund, campaign. Donors view this initiative as a test case forwhether the UN system inMyanmar can carve influence out a sphere of greater over government policy. independence, Another key and issue exert a greater is whether the

UN and INGOs can establish mechanisms

World

absorption capacity in this sector. on concentrate Like the UN agencies, most INGOs in Myanmar some (e.g. CARE, SCF-UK, humanitarian Swissaid, needs, although Concern and World development-oriented a broader implement programmes. While many international Vision) range agencies

for building CBO aid

of

Myanmar,

the great majority of UN and INGO projects are implemented ? directly at the village level, bypassing local NGOs although sometimes fostering the emergence of CBOs. Limited coordination between actors international and Myanmar can result in the former replicating programmes, indigenous local initiatives in the process. For example, in 2003 at undermining the jade mining centre of Hpakant two UN agencies, (Kachin State) three or more INGOs and two local NGOS were planning or already HIV/AIDS It is therefore encouraging that implementing projects. of international (including UN) agencies and local NGOs representatives met at the Shalom Centre inMay 2003, to discuss the coordination of activities in Kachin State. development As noted above, INGOs should endeavour to employ ? but this can create problems. decision-making positions local staff in As has been

would like todevelop deeper partnerships with civil societygroups in

Political Transition inMyanmar the case along the Thailand a "brain border, international agencies

251 inMyanmar

from have sometimesrecruitedstaff CBOs and localNGOs, contributing

towards international opportunities drain" of individuals to away from indigenous which offer higher salaries and more organizations, for skills development.

Only one Yangon-based INGO works exclusively though local partners. It receives project proposals from CBOs and local NGOs

a lack of strategic In every week, which often demonstrate planning. ? an effort to address such concerns, many national INGO staff and some from local NGOs ? have received training at specialized institutes outside Myanmar. the most Among significant capacity-building since

which,

networks is theThailand-based Spirit inEducation Movement (SEM)

1996, has provided grassroots leadership training and to several for skills and participatory techniques support management For many members of die sangha hundred Myanmar nationals. in to community this training has been their first exposure particular, development

the creation of an enabling environment, strengthening local efforts to It is vital that donors and international achieve peace and development. ? cross either via refugee communities, agencies entering Myanmar border or through Yangon ? realize that they are not operating in a void. Impressive local initiatives exist, and are worthy of support. The challenge is how overwhelming Donors of local NGOs to foster the growth of civil society, without its limited absorption capacities. on a narrow not should set of just concentrate and civil and

aid it Although therole of foreign is limited, can contributetowards

methods.

NGOs. Rather,by fostering development the professionalized (western)

society, a nexus between development democracy may gradually emerge. civil society is still underdeveloped, However, Myanmar and

civil society is a long-term re-shape state-society relations inMyanmar: vehicle for socio-political humanitarian and change. Nevertheless, assistance in remote, armed conflict-affected longer-term development areas can be implemented inways which address underlying structures of violence and injustice. Conflict resolution must go beyond the necessary first stage of ceasefire negotiation. Given that displacement may not come to an end with the cessation to of armed conflict, any negotiated settlement and centre-periphery conflicts must Myanmar's protracted state-society address issues of land and other social and economic rights, and take account of the complexity of displacement crises in rural Myanmar.

will takedecades to will be gradual. It changes comingfrom the sector

252

Ashley South

areas are of the problems faced in armed conflict-affected Many common across Myanmar. the stakes in the ceasefire zones However, areas are higher, as the breakdown of the ceasefire and adjacent process

been mixed, be devastating. the consequences of their failure would can be turned into vehicles for the if the ceasefires However, and economies, reconstruction of local communities theymay promote and over time foster the and reform in Myanmar, reconciliation emergence Humanitarian International of genuine Access peace.

development initiatives.Although the impact of the ceasefires has

would

undermine

actual

and

potential

peace-building

and

do not have direct access to most armed organizations conflict-affected zones inMyanmar. The UN system and INGOs should the government for greater access to needy populations. challenge line" are

and community implementing important humanitarian in areas of current or recent armed conflict, such projects, development as Karen State. In the context of a KNU ceasefire, and increased it crises in rural Myanmar, international attention to the humanitarian is important that aid interventions be conducted in partnership with civil society these local actors, and that opportunities of empowering are not overlooked. and national international Local, (to a very limited degree)

In the meantime, localNGOs operatingon both sides of the "front

to resettle IDPs and refugees, and reconstruct did helped organizations in the Kachin and Mon States in the 1990s. communities, displaced in these areas, refugee repatriation was arranged ceasefires Following by NGOs, (ex-)insurgent groups and local refugee committees, under both However, pressure from the host country (China and Thailand). the 1992-94 Kachin IDP and refugee resettlement (60-70,000 people), and 1996 Mon refugee repatriation (10,000 people) were undermined a lack of international support, and obstructed by the military by government. They therefore failed tomove beyond the ceasefire to address underlying issues, i.e., there was no "peace-building" of a Bottom-up Approach stage, stage.

The Limits

to democratization Critics of a civil society-based approach inMyanmar accuse local networks of being compromised and co-opted by the may ("subaltern civil society"). However, regime, or at least naively apolitical work for "development community-level from below", and build networks of independent, associations locally-rooted

many local NGOs and CBOs have forged the space within which to

participation. These

Political Transition inMyanmar undermine autonomous important the ideological and practical basis ofmilitary spaces, at least in limited spheres.

253 rule, creating

However, local NGOs and CBOs have limitedcapacities, and it is

are local associations political goals. Many (especially non-Christian) the rational-bureaucratic unfamiliar with frameworks employed by donors, which may lead to non-formal CBOs "falling beneath the radar" of international observers.17 Furthermore, the civil society sector is not immune to rivalries, opportunism, "rent-seeking" or corruption. The most substantial constraint on the growth of civil society in

? (including

to re-state

? but usually implicitly

that most

are

focused

on welfare

social change), rather than

initiatives

is government distrust. Nevertheless, the past five to ten Myanmar years have seen a partial (and contested) readjustment of state-society relations. to empower Efforts civil and support society bottom-up inMyanmar have been hostage to other political agendas democratization ? in particular, the struggle for national-level political change. The NLD and other stakeholders want to see a national/elite-level political settlement in place, before they endorse local development activities. It is argued that relief and development work "inside" the country will of government. Although the responsibility such caveats should be taken seriously, local NGOs and CBOs are able to deliver humanitarian in ways which build local capacities, and other forms of assistance and contribute towards longer-term reconstruction strengthen protection, ? efforts results which cannot be depicted as strengthening the SPDC. in the ability to support Nevertheless, many agencies are constrained the re-emergence of civil society sanctions regime. (especially US) in Myanmar, due to the western

"let the SPDC off thehook", by providing goods and services that are

Having itBothWays: Towards a Hybrid Strategy

The re-emergence of civil society networks is not in itself sufficient to transition. This will bring about national-level political require concerted, explicitly political actions by political elites. In themeantime, civil society networks can prepare theway for democratic participation, and are worthy of support in their own right? regardless of national

level politics. Myanmar presents a structured and highly dynamic environment on the ground are an essential first step towards of conflict. Ceasefires the needs of rural communities, and building local addressing and "democracy from below". In the meantime however, participation

sustainable change is stillurgentlyrequired at theelite level.

254

Ashley South

fornational-level transition, re-emergent civil society networks represent an important vehicle in for long-term, bottom-up democratization Local NGOs and CBOs promote grassroots social mobilization Myanmar.

In thecurrent with only limitedoptions available political climate,

and?

at the value, these local networks can form the base for democratization national transition is sustained, level, and help to ensure that political The promotion of civil society and takes root in local communities. to the constitutional in Myanmar relates therefore of concept

? potentially

political participation.As well as their intrinsic

in which "countervailance", sovereignty resides in plural points of to preclude with checks and balances the centralization power, of authority. is still underdeveloped; The voluntary sector inMyanmar changes International donors should therefore foster supportive, long-term to avoid Efforts should be made

coming from civil societywill be gradual, and need to be supported.

relationships with local associations.

and other of women, ethnic and religious minorities, and potentially vulnerable groups. Myanmar heeds better marginalized targeted aid but not necessarily much more money. Different actors can play different roles, based on a shared vision of a future democratic Myanmar. Some agencies will take a hard-line the regime from outside Myanmar, while against position, campaigning a to work others adopt a softer mode, inside the country. Such in line with calls by the UN Secretary General's is coordinated approach for an "orchestrated" international strategy. Myanmar Special Envoy for participation governments, and might be termed selective (or targeted) engagement

working onlywith elites: analysis and planning should focus on the

This approach is likely to appeal to regional (ASEAN and Japanese)

NOTES

1 Myanmar has had two

some opposition 2 Although activists may wish Africa. However, if it was, then Khin Nyunt Given the apparent failure of the NC,

Ne independence in 1948) and in 1974 (by the Win regime).

his position

previous

constitutions,

promulgated

in 1947

(before South figure.

is not another it so, Myanmar is the most plausible Botha is vulnerable.

3 This processwould recall thehistoricPanglongAgreementofFebruary 1947, under which leaders of some ethnic nationalities agreed to join the future Union of

Burma.

4 See InternationalCrisis Group,Myanmar Backgrounder: EthnicMinority Parties 5 See Ashley South, Mon Nationalism and CivilWar inBurma: The Golden Sheldrake (London: RoutledgeCurzon 2003), Chapter 9.

(Report no. 52-07, May 2003), <www.icg.org/home/index.cfm?id=1528&l=l>.

Political Transition inMyanmar 255

6

7 UNHCR alreadyworks with thesegovernment-organized NGOs in itsprogrammes with repatriated Rohingya refugeesinArakan (Rakhine)State. 8 These are reflectedin a "Roadmap for Union ofBurma", announced Rebuilding the in Thailand on 5 September 2003 by the Ethnic Nationalities Solidarity and CoordinationCommittee (ENSCC). 9 The Standpoint of theCease-fireGroups in Relation to the National Convention, 5 September 2004. 10 InBurmaCentre NetherlandsandTransnational Institute, Civil Society: Strengthening NGOs (Chiengmai:Silkworm Books, Possibilities and Dilemmas for International

1999), 11 South, pp. p. 8.

Ibid., pp.

293-99.

12 InRobertTaylor (ed.),Burma: Political Economy UnderMilitaryRule (Hurst2001),

161-62.

op. cit,

chap.

20.

13 UN Office of theResident Coordinator, 30May 2001. 14 Many Thailand border-based INGOs are restricted their mandates toworking in by ? it was impossible to workwith therefugees and notbe aware that their Myanmar was intimately and daily life connected to the social,military and political plight

situation across "consolidated" also more the border. there are a smaller number of however, Today are relatively cut-off from Myanmar; there are refugee camps, which INGOs on the scene. International staff (and more agency specialized) ? a the refugee camps when there were only. Ten years ago larger number were to insurgent-controlled smaller of which camps, many adjacent parts of of

much less), and are seldom rarelyspendmore than two years inThailand (often given a detailed briefingregardingthe socio-political background to the refugee in isolation fromthebiggerpictureofdevelopments in Myanmar, focusing primarily on technical mandates in thefields ofhealth or education. 15 UNDP GoverningCouncil decision no. 92/21 (June1993).

16 Humanitarian Needs Assessment Joint Kokang-Wa 17 As Ottaway and Carothers note, "professionalized to have, the administrative donors capabilities other documents donors ask of beneficiaries. Team, NGOs need unpublished report (2003). ... have, or can be trained for their own bureaucratic crisis. They therefore tend to conceive of their clients ? the refugee population ?

argument, all NGOs promote participation, basis on which is built": Marina democracy Funding Carnegie Virtue: Civil Endowment Society Aid for International

In contrast, many... informal especially types of social networks, are not set up to donor needs." However, donor support in "the areas of public health, control, agriculture, poverty reduction, and small population ? ... in the recipient countries business development through NGOs clearly have effects on the development of civil society in those countries.... to this According social movements, associations, to be administratively responsive and other and Ottaway 2000),

requirements. They can produce grantproposals (usually inEnglish)... and all the

thus empowerment, and this is the and Thomas Carothers (eds), and Democracy Promotion DC: (Washington Peace p. 13.

Ashley South is an independent consultant and analyst (currently based in Bangkok, Thailand), in ethnic politics, displacement specializing issues inMyanmar. and humanitarian

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Pemikiran Immanuel KantDokument86 SeitenPemikiran Immanuel KantAtma DewitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Receptionist - Vacancy Announcement 2023Dokument3 SeitenReceptionist - Vacancy Announcement 2023Atma DewitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Speechcraft Flyer 2022 2023Dokument1 SeiteSpeechcraft Flyer 2022 2023Atma DewitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- FA - Catalogue - Small Size-V1Dokument32 SeitenFA - Catalogue - Small Size-V1Atma DewitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- ISEF EflyerDokument4 SeitenISEF EflyerAtma DewitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Seminar PPP April 2021Dokument3 SeitenSeminar PPP April 2021Atma DewitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- UI Toastmasters Club: Time Schedule PersonDokument2 SeitenUI Toastmasters Club: Time Schedule PersonAtma DewitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Page WebsiteDokument2 SeitenPage WebsiteAtma DewitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Pol RectoratDokument3 SeitenPol RectoratAtma DewitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

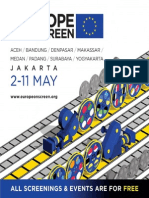

- Europe On Screen 2014 Jakarta ScheduleDokument1 SeiteEurope On Screen 2014 Jakarta ScheduleMariaYudithiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Internship Opportunity at CHARLESDokument1 SeiteInternship Opportunity at CHARLESAtma DewitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- November 2014 NewsletterDokument3 SeitenNovember 2014 NewsletterAtma DewitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exploration of The Soul in The ExplorerDokument3 SeitenExploration of The Soul in The ExplorerAtma DewitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- EOS 2014 Program BookDokument96 SeitenEOS 2014 Program BookAtma DewitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Minutes of Meeting Feb 12, 2015Dokument2 SeitenMinutes of Meeting Feb 12, 2015Atma DewitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Agenda UI Toastmasters Club - Januari 29Dokument1 SeiteAgenda UI Toastmasters Club - Januari 29Atma DewitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- UI Toastmasters Club: Time Schedule PICDokument3 SeitenUI Toastmasters Club: Time Schedule PICAtma DewitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Minutes of Meeting December 17th, 2014Dokument2 SeitenMinutes of Meeting December 17th, 2014Atma DewitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Minutes of Meeting 30 Okt 2014Dokument2 SeitenMinutes of Meeting 30 Okt 2014Atma DewitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Agenda UI Toastmasters Club - BaruDokument1 SeiteAgenda UI Toastmasters Club - BaruAtma DewitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Minutes of Meeting Feb 18th 2015Dokument2 SeitenMinutes of Meeting Feb 18th 2015Atma DewitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Minutes of Meeting Feb 4th 2015Dokument2 SeitenMinutes of Meeting Feb 4th 2015Atma DewitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Minutes of Meeting December 11th, 2014Dokument2 SeitenMinutes of Meeting December 11th, 2014Atma DewitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Agenda UI Toastmasters Club - Feb12Dokument1 SeiteAgenda UI Toastmasters Club - Feb12Atma DewitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Minutes of Meeting December 3rd, 2014Dokument2 SeitenMinutes of Meeting December 3rd, 2014Atma DewitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- February 2015 NewsletterDokument4 SeitenFebruary 2015 NewsletterAtma DewitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- March 2015 NewsletterDokument3 SeitenMarch 2015 NewsletterAtma DewitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brosur Toastmaster 3 - 3Dokument2 SeitenBrosur Toastmaster 3 - 3Atma DewitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (120)

- December 2014 NewsletterDokument2 SeitenDecember 2014 NewsletterAtma DewitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brosur CrossoverDokument2 SeitenBrosur CrossoverAtma DewitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pre-Bar Quizzer in Political Law - Part I Constitution of Government 21-30Dokument3 SeitenPre-Bar Quizzer in Political Law - Part I Constitution of Government 21-30Jayvee DividinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ord442 2018Dokument4 SeitenOrd442 2018Dandolph TanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Karm V NypaDokument9 SeitenKarm V NyparkarlinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ordinance No Blowing of HornsDokument2 SeitenOrdinance No Blowing of HornsDodj DimaculanganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Soc Sci 2Dokument4 SeitenSoc Sci 2nocelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alta Vista Golf Club NotesDokument3 SeitenAlta Vista Golf Club NotesmauNoch keine Bewertungen

- DigestDokument5 SeitenDigestMeng GoblasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kay Villegas Kami Inc. (GR No. L32485, October 22, 1970)Dokument2 SeitenKay Villegas Kami Inc. (GR No. L32485, October 22, 1970)Jolo CoronelNoch keine Bewertungen

- GK Today Current Affairs December 2015Dokument251 SeitenGK Today Current Affairs December 2015Enforcement OfficerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Macalintal vs. Comelec - SuffrageDokument2 SeitenMacalintal vs. Comelec - SuffrageManuel Joseph Franco100% (1)

- Magdalo para Sa Pagbabago vs. Commission On ElectionsDokument26 SeitenMagdalo para Sa Pagbabago vs. Commission On ElectionscyhaaangelaaaNoch keine Bewertungen

- UOI V Tulsiram PatelDokument15 SeitenUOI V Tulsiram PatelThomas Joseph67% (3)

- National Sugar Refineries Corp v. NLRC Case DigestDokument3 SeitenNational Sugar Refineries Corp v. NLRC Case DigestAl RxNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elec - Abanil Vs Justice of The Peace - Mahurom Vs COMELECDokument4 SeitenElec - Abanil Vs Justice of The Peace - Mahurom Vs COMELECMariaAyraCelinaBatacanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 117 G.R. No. 211892, December 06, 2017 - Innodata Knowledge Services, Inc., Petitioner, V. Socorro D'marDokument12 Seiten117 G.R. No. 211892, December 06, 2017 - Innodata Knowledge Services, Inc., Petitioner, V. Socorro D'marCharlene MillaresNoch keine Bewertungen

- 9th Social Science English Medium Notes by Veeresh P ArakeriDokument42 Seiten9th Social Science English Medium Notes by Veeresh P ArakeriRahul82% (22)

- 153253-1939-Gurbuxani v. Government of The PhilippinesDokument6 Seiten153253-1939-Gurbuxani v. Government of The PhilippineskarlshemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Courage vs. CIRDokument2 SeitenCourage vs. CIRMike E Dm33% (3)

- Bernabe v. Alejo, GR 140500, Jan. 21, 2002 DigestedDokument3 SeitenBernabe v. Alejo, GR 140500, Jan. 21, 2002 DigestedJireh Rarama100% (1)

- Lowell Ordered To Turn Over Records Related To Alyssa BrameDokument2 SeitenLowell Ordered To Turn Over Records Related To Alyssa BramebaystateexaminerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Roxas Vs CA Agra CaseDokument7 SeitenRoxas Vs CA Agra CaseNullus cumunisNoch keine Bewertungen

- LIM Vs Executive SecretaryDokument1 SeiteLIM Vs Executive SecretaryMan2x SalomonNoch keine Bewertungen

- 20 Years of Cordillera DayDokument15 Seiten20 Years of Cordillera Daykiwet100% (2)

- BlueBook 20th EditionDokument3 SeitenBlueBook 20th EditionHasan Al BannaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Precedent As A Source of Law and Its Historical DevelopmentDokument13 SeitenPrecedent As A Source of Law and Its Historical DevelopmentSrijan Mehrotra50% (2)

- 02-2014 Graciano Banaga LotDokument2 Seiten02-2014 Graciano Banaga LotSbGuinobatanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Executive PowersDokument2 SeitenExecutive PowersJemina VadilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jeffrey Schirripa V., 3rd Cir. (2015)Dokument3 SeitenJeffrey Schirripa V., 3rd Cir. (2015)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Public CorpDokument98 SeitenPublic CorpMeriam FernandezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pidato English Upper FormDokument5 SeitenPidato English Upper FormfaisalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Age of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the PresentVon EverandAge of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the PresentBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (6)

- From Cold War To Hot Peace: An American Ambassador in Putin's RussiaVon EverandFrom Cold War To Hot Peace: An American Ambassador in Putin's RussiaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (23)

- No Mission Is Impossible: The Death-Defying Missions of the Israeli Special ForcesVon EverandNo Mission Is Impossible: The Death-Defying Missions of the Israeli Special ForcesBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (7)

- Heretic: Why Islam Needs a Reformation NowVon EverandHeretic: Why Islam Needs a Reformation NowBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (57)

- Kilo: Inside the Deadliest Cocaine Cartels—From the Jungles to the StreetsVon EverandKilo: Inside the Deadliest Cocaine Cartels—From the Jungles to the StreetsBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (2)

- Hunting Eichmann: How a Band of Survivors and a Young Spy Agency Chased Down the World's Most Notorious NaziVon EverandHunting Eichmann: How a Band of Survivors and a Young Spy Agency Chased Down the World's Most Notorious NaziBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (157)