Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Article 1169 (Pantheleon To CB)

Hochgeladen von

Gem LiOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Article 1169 (Pantheleon To CB)

Hochgeladen von

Gem LiCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

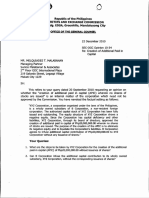

Republic of the Philippines Supreme Court Manila

SPECIAL SECOND DIVISION

POLO S. PANTALEON, Petitioner,

G.R. No. 174269 Present:

versus -

AMERICAN EXPRESS INTERNATIONAL, INC., Respondent.

CARPIO MORALES, J., Acting Chairperson, VELASCO, JR., LEONARDO-DE CASTRO, BRION, and * BERSAMIN, JJ. Promulgated:

August 25, 2010 x----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------x RESOLUTION BRION, J.: We resolve the motion for reconsideration filed by respondent American Express International, Inc. (AMEX) dated June 8, 2009,[1] seeking to reverse our Decision dated May 8, 2009 where we ruled that AMEX was guilty of culpable delay in fulfilling its obligation to its cardholder petitioner Polo Pantaleon. Based on this conclusion, we held AMEX liable for moral and exemplary damages, as well as attorneys fees and costs of litigation.[2] FACTUAL ANTECEDENTS The established antecedents of the case are narrated below. AMEX is a resident foreign corporation engaged in the business of providing credit services through the operation of a charge card system. Pantaleon has been an AMEX cardholder since 1980.[3]

In October 1991, Pantaleon, together with his wife (Julialinda), daughter (Regina), and son (Adrian Roberto), went on a guided European tour. On October 25, 1991, the tour group arrived in Amsterdam. Due to their late arrival, they postponed the tour of the city for the following day.[4] The next day, the group began their sightseeing at around 8:50 a.m. with a trip to the Coster Diamond House (Coster). To have enough time for take a guided city tour of Amsterdam before their departure scheduled on that day, the tour group planned to leave Coster by 9:30 a.m. at the latest. While at Coster, Mrs. Pantaleon decided to purchase some diamond pieces worth a total of US$13,826.00. Pantaleon presented his American Express credit card to the sales clerk to pay for this purchase. He did this at around 9:15 a.m. The sales clerk swiped the credit card and asked Pantaleon to sign the charge slip, which was then electronically referred to AMEXs Amsterdam office at 9:20 a.m.[5] At around 9:40 a.m., Coster had not received approval from AMEX for the purchase so Pantaleon asked the store clerk to cancel the sale. The store manager, however, convinced Pantaleon to wait a few more minutes. Subsequently, the store manager informed Pantaleon that AMEX was asking for bank references; Pantaleon responded by giving the names of his Philippine depository banks. At around 10 a.m., or 45 minutes after Pantaleon presented his credit card, AMEX still had not approved the purchase. Since the city tour could not begin until the Pantaleons were onboard the tour bus, Coster decided to release at around 10:05 a.m. the purchased items to Pantaleon even without AMEXs approval. When the Pantaleons finally returned to the tour bus, they found their travel companions visibly irritated. This irritation intensified when the tour guide announced that they would have to cancel the tour because of lack of time as they all had to be in Calais, Belgium by 3 p.m. to catch the ferry to London.[6] From the records, it appears that after Pantaleons purchase was transmitted for approval to AMEXsAmsterdam office at 9:20 a.m.; was referred to AMEXs Manila office at 9:33 a.m.; and was approved by theManila office at 10:19 a.m. At 10:38 a.m., AMEXs Manila office finally transmitted the Approval Code to AMEXs Amsterdam office. In all, it took AMEX a total of 78 minutes to approve Pantaleons purchase and to transmit the approval to the jewelry store.[7] After the trip to Europe, the Pantaleon family proceeded to the United States. Again, Pantaleon experienced delay in securing approval for purchases using his American Express credit card on two separate occasions. He experienced the first delay when he wanted to purchase golf equipment in the amount of US$1,475.00 at the Richard Metz Golf Studio in New York on October 30, 1991. Another delay occurred when he wanted to purchase childrens shoes worth US$87.00 at the Quiency Market in Boston on November 3, 1991.

Upon return to Manila, Pantaleon sent AMEX a letter demanding an apology for the humiliation and inconvenience he and his family experienced due to the delays in obtaining approval for his credit card purchases. AMEX responded by explaining that the delay in Amsterdam was due to the amount involved the charged purchase of US$13,826.00 deviated from Pantaleons established charge purchase pattern. Dissatisfied with this explanation, Pantaleon filed an action for damages against the credit card company with the Makati City Regional Trial Court (RTC).

On August 5, 1996, the RTC found AMEX guilty of delay, and awarded Pantaleon P500,000.00 as moral damages, P300,000.00 as exemplary damages, P100,000.00 as attorneys fees, and P85,233.01 as litigation expenses. On appeal, the CA reversed the awards.[8] While the CA recognized that delay in the nature of mora accipiendi or creditors default attended AMEXs approval of Pantaleons purchases, it disagreed with the RTCs finding that AMEX had breached its contract, noting that the delay was not attended by bad faith, malice or gross negligence. The appellate court found that AMEX exercised diligent efforts to effect the approval of Pantaleons purchases; the purchase at Coster posed particularly a problem because it was at variance with Pantaleons established charge pattern. As there was no proof that AMEX breached its contract, or that it acted in a wanton, fraudulent or malevolent manner, the appellate court ruled that AMEX could not be held liable for any form of damages. Pantaleon questioned this decision via a petition for review on certiorari with this Court. In our May 8, 2009 decision, we reversed the appellate courts decision and held that AMEX was guilty of mora solvendi, or debtors default. AMEX, as debtor, had an obligation as the credit provider to act on Pantaleons purchase requests, whether to approve or disapprove them, with timely dispatch. Based on the evidence on record, we found that AMEX failed to timely act on Pantaleons purchases. Based on the testimony of AMEXs credit authorizer Edgardo Jaurique, the approval time for credit card charges would be three to four seconds under regular circumstances. In Pantaleons case, it took AMEX 78 minutes to approve the Amsterdam purchase. We attributed this delay to AMEXs Manila credit authorizer, Edgardo Jaurique, who had to go over Pantaleons past credit history, his payment record and his credit and bank references before he approved the purchase. Finding this delay unwarranted, we reinstated the RTC decision and awarded Pantaleon moral and exemplary damages, as well as attorneys fees and costs of litigation. THE MOTION FOR RECONSIDERATION

In its motion for reconsideration, AMEX argues that this Court erred when it found AMEX guilty of culpable delay in complying with its obligation to act with timely dispatch on Pantaleons purchases. While AMEX admits that it normally takes seconds to approve charge purchases, it emphasizes that Pantaleon experienced delay in Amsterdam because his transaction was not a normal one. To recall, Pantaleon sought to charge in a single transaction jewelry items purchased from Coster in the total amount of US$13,826.00 orP383,746.16. While the total amount of Pantaleons previous purchases using his AMEX credit card did exceed US$13,826.00, AMEX points out that these purchases were made in a span of more than 10 years, not in a single transaction. Because this was the biggest single transaction that Pantaleon ever made using his AMEX credit card, AMEX argues that the transaction necessarily required the credit authorizer to carefully review Pantaleons credit history and bank references. AMEX maintains that it did this not only to ensure Pantaleons protection (to minimize the possibility that a third party was fraudulently using his credit card), but also to protect itself from the risk that Pantaleon might not be able to pay for his purchases on credit. This careful review, according to AMEX, is also in keeping with the extraordinary degree of diligence required of banks in handling its transactions. AMEX concluded that in these lights, the thorough review of Pantaleons credit record was motivated by legitimate concerns and could not be evidence of any ill will, fraud, or negligence by AMEX. AMEX further points out that the proximate cause of Pantaleons humiliation and embarrassment was his own decision to proceed with the purchase despite his awareness that the tour group was waiting for him and his wife. Pantaleon could have prevented the humiliation had he cancelled the sale when he noticed that the credit approval for the Coster purchase was unusually delayed. In his Comment dated February 24, 2010, Pantaleon maintains that AMEX was guilty of mora solvendi, or delay on the part of the debtor, in complying with its obligation to him. Based on jurisprudence, a just cause for delay does not relieve the debtor in delay from the consequences of delay; thus, even if AMEX had a justifiable reason for the delay, this reason would not relieve it from the liability arising from its failure to timely act on Pantaleons purchase. In response to AMEXs assertion that the delay was in keeping with its duty to perform its obligation with extraordinary diligence, Pantaleon claims that this duty includes the timely or prompt performance of its obligation. As to AMEXs contention that moral or exemplary damages cannot be awarded absent a finding of malice, Pantaleon argues that evil motive or design is not always necessary to support a finding of bad faith; gross negligence or wanton disregard of contractual obligations is sufficient basis for the award of moral and exemplary damages.

OUR RULING We GRANT the motion for reconsideration.

Brief historical background A credit card is defined as any card, plate, coupon book, or other credit device existing for the purpose of obtaining money, goods, property, labor or services or anything of value on credit.[9] It traces its roots to the charge card first introduced by the Diners Club in New York City in 1950.[10] American Express followed suit by introducing its own charge card to the American market in 1958.[11] In the Philippines, the now defunct Pacific Bank was responsible for bringing the first credit card into the country in the 1970s.[12] However, it was only in the early 2000s that credit card use gained wide acceptance in the country, as evidenced by the surge in the number of credit card holders then.[13] Nature of Credit Card Transactions To better understand the dynamics involved in credit card transactions, we turn to the United States case of Harris Trust & Savings Bank v. McCray[14] which explains: The bank credit card system involves a tripartite relationship between the issuer bank, the cardholder, and merchants participating in the system. The issuer bank establishes an account on behalf of the person to whom the card is issued, and the two parties enter into an agreement which governs their relationship. This agreement provides that the bank will pay for cardholders account the amount of merchandise or services purchased through the use of the credit card and will also make cash loans available to the cardholder. It also states that the cardholder shall be liable to the bank for advances and payments made by the bank and that the cardholders obligation to pay the bank shall not be affected or impaired by any dispute, claim, or demand by the cardholder with respect to any merchandise or service purchased. The merchants participating in the system agree to honor the banks credit cards. The bank irrevocably agrees to honor and pay the sales slips presented by the merchant if the merchant performs his undertakings such as checking the list of revoked cards before accepting the card. x x x. These slips are forwarded to the member bank which originally issued the card. The cardholder receives a statement from the bank periodically and may then decide whether to make payment to the bank in

full within a specified period, free of interest, or to defer payment and ultimately incur an interest charge.

We adopted a similar view in CIR v. American Express International, Inc. (Philippine branch),[15]where we also recognized that credit card issuers are not limited to banks. We said: Under RA 8484, the credit card that is issued by banks in general, or by non-banks in particular, refers to any card x x x or other credit device existing for the purpose of obtaining x x x goods x x x or services x x x on credit; and is being used usually on a revolving basis. This means that the consumer-credit arrangement that exists between the issuer and the holder of the credit card enables the latter to procure goods or services on a continuing basis as long as the outstanding balance does not exceed a specified limit. The card holder is, therefore, given the power to obtain present control of goods or service on a promise to pay for them in the future. Business establishments may extend credit sales through the use of the credit card facilities of a non-bank credit card company to avoid the risk of uncollectible accounts from their customers. Under this system, the establishments do not deposit in their bank accounts the credit card drafts that arise from the credit sales. Instead, they merely record their receivables from the credit card company and periodically send the drafts evidencing those receivables to the latter. The credit card company, in turn, sends checks as payment to these business establishments, but it does not redeem the drafts at full price. The agreement between them usually provides for discounts to be taken by the company upon its redemption of the drafts. At the end of each month, it then bills its credit card holders for their respective drafts redeemed during the previous month. If the holders fail to pay the amounts owed, the company sustains the loss.

Simply put, every credit card transaction involves three contracts, namely: (a) the sales contract between the credit card holder and the merchant or the business establishment which accepted the credit card; (b) theloan agreement between the credit card issuer and the credit card holder; and lastly, (c) the promise to paybetween the credit card issuer and the merchant or business establishment.[16] Credit card issuer cardholder relationship

When a credit card company gives the holder the privilege of charging items at establishments associated with the issuer,[17] a necessary question in a legal analysis is when does this relationship begin? There are two diverging views on the matter. In City Stores Co. v. Henderson,[18] another U.S. decision, held that: The issuance of a credit card is but an offer to extend a line of open account credit. It is unilateral and supported by no consideration. The offer may be withdrawn at any time, without prior notice, for any reason or, indeed, for no reason at all, and its withdrawal breaches no duty for there is no duty to continue it and violates no rights. Thus, under this view, each credit card transaction is considered a separate offer and acceptance. Novack v. Cities Service Oil Co.[19] echoed this view, with the court ruling that the mere issuance of a credit card did not create a contractual relationship with the cardholder. On the other end of the spectrum is Gray v. American Express Company[20] which recognized the card membership agreement itself as a binding contract between the credit card issuer and the card holder. Unlike in the Novack and the City Stores cases, however, the cardholder in Gray paid an annual fee for the privilege of being an American Express cardholder. In our jurisdiction, we generally adhere to the Gray ruling, recognizing the relationship between the credit card issuer and the credit card holder as a contractual one that is governed by the terms and conditions found in the card membership agreement.[21] This contract provides the rights and liabilities of a credit card company to its cardholders and vice versa. We note that a card membership agreement is a contract of adhesion as its terms are prepared solely by the credit card issuer, with the cardholder merely affixing his signature signifying his adhesion to these terms.[22]This circumstance, however, does not render the agreement void; we have uniformly held that contracts of adhesion are as binding as ordinary contracts, the reason being that the party who adheres to the contract is free to reject it entirely.[23] The only effect is that the terms of the contract are construed strictly against the party who drafted it.[24]

On AMEXs obligations to Pantaleon We begin by identifying the two privileges that Pantaleon assumes he is entitled to with the issuance of his AMEX credit card, and on which he anchors his claims. First, Pantaleon presumes that since his credit card has no pre-set spending limit, AMEX has the obligation to approve all his charge requests. Conversely, even if AMEX has no

such obligation, at the very least it is obliged to act on his charge requests within a specific period of time. i. Use of credit card a mere offer to enter into loan agreements

Although we recognize the existence of a relationship between the credit card issuer and the credit card holder upon the acceptance by the cardholder of the terms of the card membership agreement (customarily signified by the act of the cardholder in signing the back of the credit card), we have to distinguish this contractual relationship from the creditor-debtor relationship which only arises after the credit card issuer has approved the cardholders purchase request. The first relates merely to an agreement providing for credit facility to the cardholder. The latter involves the actual credit on loan agreement involving three contracts, namely: the sales contract between the credit card holder and the merchant or the business establishment which accepted the credit card; the loan agreement between the credit card issuer and the credit card holder; and the promise to pay between the credit card issuer and the merchant or business establishment. From the loan agreement perspective, the contractual relationship begins to exist only upon the meeting of the offer[25] and acceptance of the parties involved. In more concrete terms, when cardholders use their credit cards to pay for their purchases, they merely offer to enter into loan agreements with the credit card company. Only after the latter approves the purchase requests that the parties enter into binding loan contracts, in keeping with Article 1319 of the Civil Code, which provides: Article 1319. Consent is manifested by the meeting of the offer and the acceptance upon the thing and the cause which are to constitute the contract. The offer must be certain and the acceptance absolute. A qualified acceptance constitutes a counter-offer. This view finds support in the reservation found in the card membership agreement itself, particularly paragraph 10, which clearly states that AMEX reserve[s] the right to deny authorization for any requested Charge. By so providing, AMEX made its position clear that it has no obligation to approve any and all charge requests made by its card holders. ii. AMEX not guilty of culpable delay Since AMEX has no obligation to approve the purchase requests of its credit cardholders, Pantaleon cannot claim that AMEX defaulted in its obligation. Article 1169 of the Civil Code, which provides the requisites to hold a debtor guilty of culpable delay, states: Article 1169. Those obliged to deliver or to do something incur in delay from the time the obligee judicially or extrajudicially demands from them the fulfillment of their obligation. x x x.

The three requisites for a finding of default are: (a) that the obligation is demandable and liquidated; (b) the debtor delays performance; and (c) the creditor judicially or extrajudicially requires the debtors performance.[26] Based on the above, the first requisite is no longer met because AMEX, by the express terms of the credit card agreement, is not obligated to approve Pantaleons purchase request. Without a demandable obligation, there can be no finding of default. Apart from the lack of any demandable obligation, we also find that Pantaleon failed to make the demand required by Article 1169 of the Civil Code. As previously established, the use of a credit card to pay for a purchase is only an offer to the credit card company to enter a loan agreement with the credit card holder. Before the credit card issuer accepts this offer, no obligation relating to the loan agreement exists between them. On the other hand, a demand is defined as the assertion of a legal right; xxx an asking with authority, claiming or challenging as due.[27] A demand presupposes the existence of an obligation between the parties. Thus, every time that Pantaleon used his AMEX credit card to pay for his purchases, what the stores transmitted to AMEX were his offers to execute loan contracts. These obviously could not be classified as the demand required by law to make the debtor in default, given that no obligation could arise on the part of AMEX until after AMEX transmitted its acceptance of Pantaleons offers. Pantaleons act of insisting on and waiting for the charge purchases to be approved by AMEX[28] is not the demand contemplated by Article 1169 of the Civil Code. For failing to comply with the requisites of Article 1169, Pantaleons charge that AMEX is guilty of culpable delay in approving his purchase requests must fail. iii. On AMEXs obligation to act on the offer within a specific period of time Even assuming that AMEX had the right to review his credit card history before it approved his purchase requests, Pantaleon insists that AMEX had an obligation to act on his purchase requests, either to approve or deny, in a matter of seconds or in timely dispatch. Pantaleon impresses upon us the existence of this obligation by emphasizing two points: (a) his card has no pre-set spending limit; and (b) in his twelve years of using his AMEX card, AMEX had always approved his charges in a matter of seconds. Pantaleons assertions fail to convince us. We originally held that AMEX was in culpable delay when it acted on the Coster transaction, as well as the two other transactions in the United States which took AMEX

approximately 15 to 20 minutes to approve. This conclusion appears valid and reasonable at first glance, comparing the time it took to finally get the Coster purchase approved (a total of 78 minutes), to AMEXs normal approval time of three to four seconds (based on the testimony of Edgardo Jaurigue, as well as Pantaleons previous experience). We come to a different result, however, after a closer look at the factual and legal circumstances of the case. AMEXs credit authorizer, Edgardo Jaurigue, explained that having no pre-set spending limit in a credit card simply means that the charges made by the cardholder are approved based on his ability to pay, as demonstrated by his past spending, payment patterns, and personal resources.[29] Nevertheless, every time Pantaleon charges a purchase on his credit card, the credit card company still has to determine whether it will allow this charge, based on his past credit history. This right to review a card holders credit history, although not specifically set out in the card membership agreement, is a necessary implication of AMEXs right to deny authorization for any requested charge. As for Pantaleons previous experiences with AMEX (i.e., that in the past 12 years, AMEX has always approved his charge requests in three or four seconds), this record does not establish that Pantaleon had a legally enforceable obligation to expect AMEX to act on his charge requests within a matter of seconds. For one, Pantaleon failed to present any evidence to support his assertion that AMEX acted on purchase requests in a matter of three or four seconds as an established practice. More importantly, even if Pantaleon did prove that AMEX, as a matter of practice or custom, acted on its customers purchase requests in a matter of seconds, this would still not be enough to establish a legally demandable right; as a general rule, a practice or custom is not a source of a legally demandable or enforceable right.[30] We next examine the credit card membership agreement, the contract that primarily governs the relationship between AMEX and Pantaleon. Significantly, there is no provision in this agreement that obligates AMEX to act on all cardholder purchase requests within a specifically defined period of time. Thus, regardless of whether the obligation is worded was to act in a matter of seconds or to act in timely dispatch, the fact remains that no obligation exists on the part of AMEX to act within a specific period of time. Even Pantaleon admits in his testimony that he could not recall any provision in the Agreement that guaranteed AMEXs approval of his charge requests within a matter of minutes.[31] Nor can Pantaleon look to the law or government issuances as the source of AMEXs alleged obligation to act upon his credit card purchases within a matter of seconds. As the following survey of Philippine law on credit card transactions demonstrates, the State does not require credit card companies to act upon its cardholders purchase requests within a specific period of time. Republic Act No. 8484 (RA 8484), or the Access Devices Regulation Act of 1998, approved onFebruary 11, 1998, is the controlling legislation

that regulates the issuance and use of access devices, [32] including credit cards. The more salient portions of this law include the imposition of the obligation on a credit card company to disclose certain important financial information[33] to credit card applicants, as well as a definition of the acts that constitute access device fraud. As financial institutions engaged in the business of providing credit, credit card companies fall under thesupervisory powers of the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP).[34] BSP Circular No. 398 dated August 21, 2003embodies the BSPs policy when it comes to credit cards The Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) shall foster the development of consumer credit through innovative products such as credit cards under conditions of fair and sound consumer credit practices. The BSP likewise encourages competition and transparency to ensure more efficient delivery of services and fair dealings with customers. (Emphasis supplied) Based on this Circular, x x x [b]efore issuing credit cards, banks and/or their subsidiary credit card companies must exercise proper diligence by ascertaining that applicants possess good credit standing and are financially capable of fulfilling their credit commitments.[35] As the above-quoted policy expressly states, the general intent is to foster fair and sound consumer credit practices. Other than BSP Circular No. 398, a related circular is BSP Circular No. 454, issued on September 24, 2004, but this circular merely enumerates the unfair collection practices of credit card companies a matter not relevant to the issue at hand. In light of the foregoing, we find and so hold that AMEX is neither contractually bound nor legally obligated to act on its cardholders purchase requests within any specific period of time, much less a period of a matter of seconds that Pantaleon uses as his standard. The standard therefore is implicit and, as in all contracts, must be based on fairness and reasonableness, read in relation to the Civil Code provisions on human relations, as will be discussed below. AMEX acted with good faith Thus far, we have already established that: (a) AMEX had neither a contractual nor a legal obligation to act upon Pantaleons purchases within a specific period of time; and (b) AMEX has a right to review a cardholders credit card history. Our recognition of these entitlements, however, does not give AMEX an unlimited right to put off action on cardholders purchase requests for indefinite periods of time. In acting on cardholders purchase requests, AMEX must take care not to abuse its rights and cause injury to its clients and/or third persons. We cite in this regard Article 19, in conjunction with Article 21, of the Civil Code, which provide:

Article 19. Every person must, in the exercise of his rights and in the performance of his duties, act with justice, give everyone his due and observe honesty and good faith. Article 21. Any person who willfully causes loss or injury to another in a manner that is contrary to morals, good customs or public policy shall compensate the latter for the damage. Article 19 pervades the entire legal system and ensures that a person suffering damage in the course of anothers exercise of right or performance of duty, should find himself without relief.[36] It sets the standard for the conduct of all persons, whether artificial or natural, and requires that everyone, in the exercise of rights and the performance of obligations, must: (a) act with justice, (b) give everyone his due, and (c) observe honesty and good faith. It is not because a person invokes his rights that he can do anything, even to the prejudice and disadvantage of another.[37] While Article 19 enumerates the standards of conduct, Article 21 provides the remedy for the person injured by the willful act, an action for damages. We explained how these two provisions correlate with each other in GF Equity, Inc. v. Valenzona:[38] [Article 19], known to contain what is commonly referred to as the principle of abuse of rights, sets certain standards which must be observed not only in the exercise of one's rights but also in the performance of one's duties. These standards are the following: to act with justice; to give everyone his due; and to observe honesty and good faith. The law, therefore, recognizes a primordial limitation on all rights; that in their exercise, the norms of human conduct set forth in Article 19 must be observed. A right, though by itself legal because recognized or granted by law as such, may nevertheless become the source of some illegality. When a right is exercised in a manner which does not conform with the norms enshrined in Article 19 and results in damage to another, a legal wrong is thereby committed for which the wrongdoer must be held responsible. But while Article 19 lays down a rule of conduct for the government of human relations and for the maintenance of social order, it does not provide a remedy for its violation. Generally, an action for damages under either Article 20 or Article 21 would be proper. In the context of a credit card relationship, although there is neither a contractual stipulation nor a specific law requiring the credit card issuer to act on the credit card holders offer within a definite period of time, these principles provide the standard by which to judge AMEXs actions. According to Pantaleon, even if AMEX did have a right to review his charge purchases, it abused this right when it unreasonably delayed the processing of the Coster charge purchase, as well as his purchase requests at the Richard Metz Golf

Studio and Kids Unlimited Store; AMEX should have known that its failure to act immediately on charge referrals would entail inconvenience and result in humiliation, embarrassment, anxiety and distress to its cardholders who would be required to wait before closing their transactions.[39] It is an elementary rule in our jurisdiction that good faith is presumed and that the burden of proving bad faith rests upon the party alleging it. [40] Although it took AMEX some time before it approved Pantaleons three charge requests, we find no evidence to suggest that it acted with deliberate intent to cause Pantaleon any loss or injury, or acted in a manner that was contrary to morals, good customs or public policy. We give credence to AMEXs claim that its review procedure was done to ensure Pantaleons own protection as a cardholder and to prevent the possibility that the credit card was being fraudulently used by a third person. Pantaleon countered that this review procedure is primarily intended to protect AMEXs interests, to make sure that the cardholder making the purchase has enough means to pay for the credit extended. Even if this were the case, however, we do not find any taint of bad faith in such motive. It is but natural for AMEX to want to ensure that it will extend credit only to people who will have sufficient means to pay for their purchases. AMEX, after all, is running a business, not a charity, and it would simply be ludicrous to suggest that it would not want to earn profit for its services. Thus, so long as AMEX exercises its rights, performs its obligations, and generally acts with good faith, with no intent to cause harm, even if it may occasionally inconvenience others, it cannot be held liable for damages. We also cannot turn a blind eye to the circumstances surrounding the Coster transaction which, in our opinion, justified the wait. In Edgardo Jaurigues own words: Q 21: With reference to the transaction at the Coster Diamond House covered by Exhibit H, also Exhibit 4 for the defendant, the approval came at 2:19 a.m. after the request was relayed at 1:33 a.m., can you explain why the approval came after about 46 minutes, more or less? A21: Because we have to make certain considerations and evaluations of [Pantaleons] past spending pattern with [AMEX] at that time before approving plaintiffs request because [Pantaleon] was at that time making his very first singlecharge purchase of US$13,826 [this is below the US$16,112.58 actually billed and paid for by the plaintiff because the difference was already automatically approved by [AMEX] office in Netherland[s] and the record of [Pantaleons] past spending with [AMEX] at that time does not favorably support his ability to pay for such purchase. In fact, if the foregoing internal policy of [AMEX] had been strictly followed, the transaction would not have been approved at all considering that the past spending pattern of the plaintiff with [AMEX] at that time does not support his ability to pay for such purchase.[41]

x x x x Q: Why did it take so long? A: It took time to review the account on credit, so, if there is any delinquencies [sic] of the cardmember. There are factors on deciding the charge itself which are standard measures in approving the authorization. Now in the case of Mr. Pantaleon although his account is single charge purchase of US$13,826. [sic] this is below the US$16,000. plus actually billed x x x we would have already declined the charge outright and asked him his bank account to support his charge. But due to the length of his membership as cardholder we had to make a decision on hand.[42] As Edgardo Jaurigue clarified, the reason why Pantaleon had to wait for AMEXs approval was because he had to go over Pantaleons credit card history for the past twelve months.[43] It would certainly be unjust for us to penalize AMEX for merely exercising its right to review Pantaleons credit history meticulously. Finally, we said in Garciano v. Court of Appeals that the right to recover [moral damages] under Article 21 is based on equity, and he who comes to court to demand equity, must come with clean hands. Article 21 should be construed as granting the right to recover damages to injured persons who are not themselves at fault.[44] As will be discussed below, Pantaleon is not a blameless party in all this. Pantaleons action was the proximate cause for his injury Pantaleon mainly anchors his claim for moral and exemplary damages on the embarrassment and humiliation that he felt when the European tour group had to wait for him and his wife for approximately 35 minutes, and eventually had to cancel the Amsterdam city tour. After thoroughly reviewing the records of this case, we have come to the conclusion that Pantaleon is the proximate cause for this embarrassment and humiliation. As borne by the records, Pantaleon knew even before entering Coster that the tour group would have to leave the store by 9:30 a.m. to have enough time to take the city tour of Amsterdam before they left the country. After 9:30 a.m., Pantaleons son, who had boarded the bus ahead of his family, returned to the store to inform his family that they were the only ones not on the bus and that the entire tour group was waiting for them. Significantly, Pantaleon tried to cancel the sale at 9:40 a.m. because he did not want to cause any inconvenience to the tour group. However, when Costers sale manager asked him to wait a few more minutes for the credit card approval, he agreed, despite the knowledge that he had already caused a 10-minute delay and that the city tour could not start without him.

In Nikko Hotel Manila Garden v. Reyes,[45] we ruled that a person who knowingly and voluntarily exposes himself to danger cannot claim damages for the resulting injury: The doctrine of volenti non fit injuria (to which a person assents is not esteemed in law as injury) refers to self-inflicted injury or to the consent to injury which precludes the recovery of damages by one who has knowingly and voluntarily exposed himself to danger, even if he is not negligent in doing so.

This doctrine, in our view, is wholly applicable to this case. Pantaleon himself testified that the most basic rule when travelling in a tour group is that you must never be a cause of any delay because the schedule is very strict.[46] When Pantaleon made up his mind to push through with his purchase, he must have known that the group would become annoyed and irritated with him. This was the natural, foreseeable consequence of his decision to make them all wait. We do not discount the fact that Pantaleon and his family did feel humiliated and embarrassed when they had to wait for AMEX to approve the Coster purchase in Amsterdam. We have to acknowledge, however, that Pantaleon was not a helpless victim in this scenario at any time, he could have cancelled the sale so that the group could go on with the city tour. But he did not. More importantly, AMEX did not violate any legal duty to Pantaleon under the circumstances under the principle of damnum absque injuria, or damages without legal wrong, loss without injury.[47] As we held inBPI Express Card v. CA:[48] We do not dispute the findings of the lower court that private respondent suffered damages as a result of the cancellation of his credit card. However, there is a material distinction between damages and injury. Injury is the illegal invasion of a legal right; damage is the loss, hurt, or harm which results from the injury; and damages are the recompense or compensation awarded for the damage suffered. Thus, there can be damage without injury in those instances in which the loss or harm was not the result of a violation of a legal duty. In such cases, the consequences must be borne by the injured person alone, the law affords no remedy for damages resulting from an act which does not amount to a legal injury or wrong. These situations are often called damnum absque injuria. In other words, in order that a plaintiff may maintain an action for the injuries of which he complains, he must establish that such injuries resulted from a breach of duty which the defendant owed to the plaintiff - a concurrence of injury to the plaintiff and legal responsibility by the person causing it. The underlying basis for the award of tort damages is the premise that an individual was injured in contemplation of law. Thus, there must first be a breach of some duty and the imposition of liability for

that breach before damages may be awarded; and the breach of such duty should be the proximate cause of the injury. Pantaleon is not entitled to damages Because AMEX neither breached its contract with Pantaleon, nor acted with culpable delay or the willful intent to cause harm, we find the award of moral damages to Pantaleon unwarranted. Similarly, we find no basis to award exemplary damages. In contracts, exemplary damages can only be awarded if a defendant acted in a wanton, fraudulent, reckless, oppressive or malevolent manner.[49] The plaintiff must also show that he is entitled to moral, temperate, or compensatory damages before the court may consider the question of whether or not exemplary damages should be awarded.[50] As previously discussed, it took AMEX some time to approve Pantaleons purchase requests because it had legitimate concerns on the amount being charged; no malicious intent was ever established here. In the absence of any other damages, the award of exemplary damages clearly lacks legal basis. Neither do we find any basis for the award of attorneys fees and costs of litigation. No premium should be placed on the right to litigate and not every winning party is entitled to an automatic grant of attorney's fees.[51] To be entitled to attorneys fees and litigation costs, a party must show that he falls under one of the instances enumerated in Article 2208 of the Civil Code.[52] This, Pantaleon failed to do. Since we eliminated the award of moral and exemplary damages, so must we delete the award for attorney's fees and litigation expenses. Lastly, although we affirm the result of the CA decision, we do so for the reasons stated in this Resolution and not for those found in the CA decision. WHEREFORE, premises considered, we SET ASIDE our May 8, 2009 Decision and GRANT the present motion for reconsideration. The Court of Appeals Decision dated August 18, 2006 is herebyAFFIRMED. No costs. SO ORDERED.

FIRST DIVISION

[G.R. No. 115129. February 12, 1997]

IGNACIO BARZAGA, petitioner, ALVIAR,respondents.

vs. COURT

OF

APPEALS

and

ANGELITO

DECISION BELLOSILLO, J.: The Fates ordained that Christmas 1990 be bleak for Ignacio Barzaga and his family. On the nineteenth of December Ignacio's wife succumbed to a debilitating ailment after prolonged pain and suffering. Forewarned by her attending physicians of her impending death, she expressed her wish to be laid to rest before Christmas day to spare her family from keeping lonely vigil over her remains while the whole of Christendom celebrate the Nativity of their Redeemer. Drained to the bone from the tragedy that befell his family yet preoccupied with overseeing the wake for his departed wife, Ignacio Barzaga set out to arrange for her interment on the twenty-fourth of December in obedience semper fidelis to her dying wish. But her final entreaty, unfortunately, could not be carried out. Dire events conspired to block his plans that forthwith gave him and his family their gloomiest Christmas ever. This is Barzaga's story. On 21 December 1990, at about three o`clock in the afternoon, he went to the hardware store of respondent Angelito Alviar to inquire about the availability of certain materials to be used in the construction of a niche for his wife. He also asked if the materials could be delivered at once. Marina Boncales, Alviar's storekeeper, replied that she had yet to verify if the store had pending deliveries that afternoon because if there were then all subsequent purchases would have to be delivered the following day. With that reply petitioner left. At seven o' clock the following morning, 22 December, Barzaga returned to Alviar's hardware store to follow up his purchase of construction materials. He told the store employees that the materials he was buying would have to be delivered at the Memorial Cemetery in Dasmarias, Cavite, by eight o'clock that morning since his hired workers were already at the burial site and time was of the essence. Marina Boncales agreed to deliver the items at the designated time, date and place. With this assurance, Barzaga purchased the materials and paid in full the amount of P2,110.00. Thereafter he joined his workers at the cemetery, which was only a kilometer away, to await the delivery. The construction materials did not arrive at eight o'clock as promised. At nine o' clock, the delivery was still nowhere in sight. Barzaga returned to the hardware store to inquire about the delay. Boncales assured him that although the delivery truck was not yet around it had already left the garage and that as soon as it arrived the materials would be brought over to the cemetery in no time at all. That left petitioner no choice but to rejoin his workers at the memorial park and wait for the materials. By ten o'clock, there was still no delivery. This prompted petitioner to return to the store to inquire about the materials. But he received the same answer from respondent's employees who even cajoled him to go back to the burial place as they would just follow with his construction materials.

After hours of waiting - which seemed interminable to him - Barzaga became extremely upset. He decided to dismiss his laborers for the day. He proceeded to the police station, which was just nearby, and lodged a complaint against Alviar. He had his complaint entered in the police blotter. When he returned again to the store he saw the delivery truck already there but the materials he purchased were not yet ready for loading. Distressed that Alviar's employees were not the least concerned, despite his impassioned pleas, Barzaga decided to cancel his transaction with the store and look for construction materials elsewhere. In the afternoon of that day, petitioner was able to buy from another store. But since darkness was already setting in and his workers had left, he made up his mind to start his project the following morning, 23 December. But he knew that the niche would not be finish in time for the scheduled burial the following day. His laborers had to take a break on Christmas Day and they could only resume in the morning of the twentysixth. The niche was completed in the afternoon and Barzaga's wife was finally laid to rest. However, it was two-and-a-half (2-1/2) days behind schedule. On 21 January 1991, tormented perhaps by his inability to fulfill his wife's dying wish, Barzaga wrote private respondent Alviar demanding recompense for the damage he suffered. Alviar did not respond. Consequently, petitioner sued him before the Regional Trial Court.[1] Resisting petitioner's claim, private respondent contended that legal delay could not be validly ascribed to him because no specific time of delivery was agreed upon between them. He pointed out that the invoices evidencing the sale did not contain any stipulation as to the exact time of delivery and that assuming that the materials were not delivered within the period desired by petitioner, the delivery truck suffered a flat tire on the way to the store to pick up the materials. Besides, his men were ready to make the delivery by ten-thirty in the morning of 22 December but petitioner refused to accept them. According to Alviar, it was this obstinate refusal of petitioner to accept delivery that caused the delay in the construction of the niche and the consequent failure of the family to inter their loved one on the twenty-fourth of December, and that, if at all, it was petitioner and no other who brought about all his personal woes. Upholding the proposition that respondent incurred in delay in the delivery of the construction materials resulting in undue prejudice to petitioner, the trial court ordered respondent Alviar to pay petitioner (a) P2,110.00 as refund for the purchase price of the materials with interest per annum computed at the legal rate from the date of the filing of the complaint, (b) P5,000.00 as temperate damages, (c) P20,000.00 as moral damages, (d) P5,000.00 as litigation expenses, and (e) P5,000.00 as attorney's fees. On appeal, respondent Court of Appeals reversed the lower court and ruled that there was no contractual commitment as to the exact time of delivery since this was not indicated in the invoice receipts covering the sale.[2] The arrangement to deliver the materials merely implied that delivery should be made within a reasonable time but that the conclusion that since petitioner's workers were already at the graveyard the delivery had to be made at that precise moment, is non-sequitur. The Court of Appeals also held that assuming that there was delay,

petitioner still had sufficient time to construct the tomb and hold his wife's burial as she wished. We sustain the trial court. An assiduous scrutiny of the record convinces us that respondent Angelito Alviar was negligent and incurred in delay in the performance of his contractual obligation. This sufficiently entitles petitioner Ignacio Barzaga to be indemnified for the damage he suffered as a consequence of delay or a contractual breach. The law expressly provides that those who in the performance of their obligation are guilty of fraud, negligence, or delay and those who in any manner contravene the tenor thereof, are liable for damages.[3] Contrary to the appellate court's factual determination, there was a specific time agreed upon for the delivery of the materials to the cemetery. Petitioner went to private respondent's store on 21 December precisely to inquire if the materials he intended to purchase could be delivered immediately. But he was told by the storekeeper that if there were still deliveries to be made that afternoon his order would be delivered the following day. With this in mind Barzaga decided to buy the construction materials the following morning after he was assured of immediate delivery according to his time frame. The argument that the invoices never indicated a specific delivery time must fall in the face of the positive verbal commitment of respondent's storekeeper. Consequently it was no longer necessary to indicate in the invoices the exact time the purchased items were to be brought to the cemetery. In fact, storekeeper Boncales admitted that it was her custom not to indicate the time of delivery whenever she prepared invoices.[4] Private respondent invokes fortuitous event as his handy excuse for that "bit of delay" in the delivery of petitioner's purchases. He maintains that Barzaga should have allowed his delivery men a little more time to bring the construction materials over to the cemetery since a few hours more would not really matter and considering that his truck had a flat tire. Besides, according to him, Barzaga still had sufficient time to build the tomb for his wife. This is a gratuitous assertion that borders on callousness. Private respondent had no right to manipulate petitioner's timetable and substitute it with his own. Petitioner had a deadline to meet. A few hours of delay was no piddling matter to him who in his bereavement had yet to attend to other pressing family concerns. Despite this, respondent's employees still made light of his earnest importunings for an immediate delivery. As petitioner bitterly declared in court " x x x they (respondent's employees) were making a fool out of me."[5] We also find unacceptable respondent's justification that his truck had a flat tire, for this event, if indeed it happened, was forseeable according to the trial court, and as such should have been reasonably guarded against. The nature of private respondent's business requires that he should be ready at all times to meet contingencies of this kind. One piece of testimony by respondent's witness Marina Boncales has caught our attention - that the delivery truck arrived a little late than usual because it came from a delivery of materials in Langcaan, Dasmarias, Cavite.[6] Significantly, this information was withheld by Boncales from petitioner when the latter was negotiating with her for the purchase of construction materials. Consequently, it is not unreasonable to

suppose that had she told petitioner of this fact and that the delivery of the materials would consequently be delayed, petitioner would not have bought the materials from respondent's hardware store but elsewhere which could meet his time requirement. The deliberate suppression of this information by itself manifests a certain degree of bad faith on the part of respondent's storekeeper. The appellate court appears to have belittled petitioner's submission that under the prevailing circumstances time was of the essence in the delivery of the materials to the grave site. However, we find petitioner's assertion to be anchored on solid ground. The niche had to be constructed at the very least on the twenty-second of December considering that it would take about two (2) days to finish the job if the interment was to take place on the twenty-fourth of the month. Respondent's delay in the delivery of the construction materials wasted so much time that construction of the tomb could start only on the twenty-third. It could not be ready for the scheduled burial of petitioner's wife. This undoubtedly prolonged the wake, in addition to the fact that work at the cemetery had to be put off on Christmas day. This case is clearly one of non-performance of a reciprocal obligation.[7] In their contract of purchase and sale, petitioner had already complied fully with what was required of him as purchaser, i.e., the payment of the purchase price ofP2,110.00. It was incumbent upon respondent to immediately fulfill his obligation to deliver the goods otherwise delay would attach. We therefore sustain the award of moral damages. It cannot be denied that petitioner and his family suffered wounded feelings, mental anguish and serious anxiety while keeping watch on Christmas day over the remains of their loved one who could not be laid to rest on the date she herself had chosen. There is no gainsaying the inexpressible pain and sorrow Ignacio Barzaga and his family bore at that moment caused no less by the ineptitude, cavalier behavior and bad faith of respondent and his employees in the performance of an obligation voluntarily entered into. We also affirm the grant of exemplary damages. The lackadaisical and feckless attitude of the employees of respondent over which he exercised supervisory authority indicates gross negligence in the fulfillment of his business obligations. Respondent Alviar and his employees should have exercised fairness and good judgment in dealing with petitioner who was then grieving over the loss of his wife. Instead of commiserating with him, respondent and his employees contributed to petitioner's anguish by causing him to bear the agony resulting from his inability to fulfill his wife's dying wish. We delete however the award of temperate damages. Under Art. 2224 of the Civil Code, temperate damages are more than nominal but less than compensatory, and may be recovered when the court finds that some pecuniary loss has been suffered but the amount cannot, from the nature of the case, be proved with certainty. In this case, the trial court found that plaintiff suffered damages in the form of wages for the hired workers for 22 December 1990 and expenses incurred during the extra two (2) days of the wake. The record however does not show that petitioner presented proof of the actual amount of expenses he incurred which seems to be the reason the trial court awarded to him temperate damages instead. This is an erroneous application of the

concept of temperate damages. While petitioner may have indeed suffered pecuniary losses, these by their very nature could be established with certainty by means of payment receipts. As such, the claim falls unequivocally within the realm of actual or compensatory damages. Petitioner's failure to prove actual expenditure consequently conduces to a failure of his claim. For in determining actual damages, the court cannot rely on mere assertions, speculations, conjectures or guesswork but must depend on competent proof and on the best evidence obtainable regarding the actual amount of loss.[8] We affirm the award of attorney's fees and litigation expenses. Award of damages, attorney's fees and litigation costs is left to the sound discretion of the court, and if such discretion be well exercised, as in this case, it will not be disturbed on appeal.[9] WHEREFORE, the decision of the Court of Appeals is REVERSED and SET ASIDE except insofar as it GRANTED on a motion for reconsideration the refund by private respondent of the amount of P2,110.00 paid by petitioner for the construction materials. Consequently, except for the award of P5,000.00 as temperate damages which we delete, the decision of the Regional Trial Court granting petitioner (a) P2,110.00 as refund for the value of materials with interest computed at the legal rate per annum from the date of the filing of the case; (b) P20,000.00 as moral damages; (c)P10,000.00 as exemplary damages; (d) P5,000.00 as litigation expenses; and (4) P5,000.00 as attorney's fees, is AFFIRMED. No costs. SO ORDERED. Padilla, (Chairman), Vitug, Kapunan, and Hermosisima, Jr., JJ., concur. Republic of the Philippines SUPREME COURT Manila SECOND DIVISION G.R. No. 145483 November 19, 2004

LORENZO SHIPPING CORP., petitioner, vs. BJ MARTHEL INTERNATIONAL, INC., respondent.

DECISION CHICO-NAZARIO, J.: This is a petition for review seeking to set aside the Decision1 of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. CV No. 54334 and its Resolution denying petitioner's motion for reconsideration. The factual antecedents of this case are as follows:

Petitioner Lorenzo Shipping Corporation is a domestic corporation engaged in coastwise shipping. It used to own the cargo vessel M/V Dadiangas Express. Upon the other hand, respondent BJ Marthel International, Inc. is a business entity engaged in trading, marketing, and selling of various industrial commodities. It is also an importer and distributor of different brands of engines and spare parts. From 1987 up to the institution of this case, respondent supplied petitioner with spare parts for the latter's marine engines. Sometime in 1989, petitioner asked respondent for a quotation for various machine parts. Acceding to this request, respondent furnished petitioner with a formal quotation,2 thus: May 31, 1989 MINQ-6093 LORENZO SHIPPING LINES Pier 8, North Harbor Manila SUBJECT: PARTS FOR ENGINE MODEL MITSUBISHI 6UET 52/60 Dear Mr. Go: We are pleased to submit our offer for your above subject requirements. Description Nozzle Tip Plunger & Barrel Cylinder Head Cylinder Liner Qty. 6 pcs. 6 pcs. Unit Price P 5,520.00 27,630.00 Total Price 33,120.00 165,780.00

2 pcs. 1 set

1,035,000.00

2,070,000.00 477,000.00 P2,745,900.00

TOTAL PRICE FOB MANILA ___________

DELIVERY: Within 2 months after receipt of firm order. TERMS: 25% upon delivery, balance payable in 5 bi-monthly equal

Installment[s] not to exceed 90 days. We trust you find our above offer acceptable and look forward to your most valued order. Very truly yours, (SGD) HENRY PAJARILLO Sales Manager Petitioner thereafter issued to respondent Purchase Order No. 13839,3 dated 02 November 1989, for the procurement of one set of cylinder liner, valued at P477,000, to be used for M/V Dadiangas Express. The purchase order was co-signed by Jose Go, Jr., petitioner's vice-president, and Henry Pajarillo. Quoted hereunder is the pertinent portion of the purchase order: Name of Description CYL. LINER M/E NOTHING FOLLOW INV. # TERM OF PAYMENT: 25% DOWN PAYMENT 5 BI-MONTHLY INSTALLMENT[S] Instead of paying the 25% down payment for the first cylinder liner, petitioner issued in favor of respondent ten postdated checks4 to be drawn against the former's account with Allied Banking Corporation. The checks were supposed to represent the full payment of the aforementioned cylinder liner. Subsequently, petitioner issued Purchase Order No. 14011, 5 dated 15 January 1990, for yet another unit of cylinder liner. This purchase order stated the term of payment to be "25% upon delivery, balance payable in 5 bi-monthly equal installment[s]."6 Like the purchase order of 02 November 1989, the second purchase order did not state the date of the cylinder liner's delivery. On 26 January 1990, respondent deposited petitioner's check that was postdated 18 January 1990, however, the same was dishonored by the drawee bank due to insufficiency of funds. The remaining nine postdated checks were eventually returned by respondent to petitioner. Qty. Amount

1 SET

P477,000.00

The parties presented disparate accounts of what happened to the check which was previously dishonored. Petitioner claimed that it replaced said check with a good one, the proceeds of which were applied to its other obligation to respondent. For its part, respondent insisted that it returned said postdated check to petitioner. Respondent thereafter placed the order for the two cylinder liners with its principal in Japan, Daiei Sangyo Co. Ltd., by opening a letter of credit on 23 February 1990 under its own name with the First Interstate Bank of Tokyo. On 20 April 1990, Pajarillo delivered the two cylinder liners at petitioner's warehouse in North Harbor, Manila. The sales invoices7 evidencing the delivery of the cylinder liners both contain the notation "subject to verification" under which the signature of Eric Go, petitioner's warehouseman, appeared. Respondent thereafter sent a Statement of Account dated 15 November 1990 8 to petitioner. While the other items listed in said statement of account were fully paid by petitioner, the two cylinder liners delivered to petitioner on 20 April 1990 remained unsettled. Consequently, Mr. Alejandro Kanaan, Jr., respondent's vice-president, sent a demand letter dated 02 January 19919 to petitioner requiring the latter to pay the value of the cylinder liners subjects of this case. Instead of heeding the demand of respondent for the full payment of the value of the cylinder liners, petitioner sent the former a letter dated 12 March 199110 offering to pay only P150,000 for the cylinder liners. In said letter, petitioner claimed that as the cylinder liners were delivered late and due to the scrapping of the M/V Dadiangas Express, it (petitioner) would have to sell the cylinder liners in Singapore and pay the balance from the proceeds of said sale. Shortly thereafter, another demand letter dated 27 March 199111 was furnished petitioner by respondent's counsel requiring the former to settle its obligation to respondent together with accrued interest and attorney's fees. Due to the failure of the parties to settle the matter, respondent filed an action for sum of money and damages before the Regional Trial Court (RTC) of Makati City. In its complaint,12 respondent (plaintiff below) alleged that despite its repeated oral and written demands, petitioner obstinately refused to settle its obligations. Respondent prayed that petitioner be ordered to pay for the value of the cylinder liners plus accrued interest of P111,300 as of May 1991 and additional interest of 14% per annum to be reckoned from June 1991 until the full payment of the principal; attorney's fees; costs of suits; exemplary damages; actual damages; and compensatory damages. On 25 July 1991, and prior to the filing of a responsive pleading, respondent filed an amended complaint with preliminary attachment pursuant to Sections 2 and 3, Rule 57 of the then Rules of Court.13 Aside from the prayer for the issuance of writ of preliminary attachment, the amendments also pertained to the issuance by petitioner of the postdated checks and the amounts of damages claimed. In an Order dated 25 July 1991,14 the court a quo granted respondent's prayer for the issuance of a preliminary attachment. On 09 August 1991, petitioner filed an Urgent ExParte Motion to Discharge Writ of Attachment15attaching thereto a counter-bond as

required by the Rules of Court. On even date, the trial court issued an Order16 lifting the levy on petitioner's properties and the garnishment of its bank accounts. Petitioner afterwards filed its Answer17 alleging therein that time was of the essence in the delivery of the cylinder liners and that the delivery on 20 April 1990 of said items was late as respondent committed to deliver said items "within two (2) months after receipt of firm order"18 from petitioner. Petitioner likewise sought counterclaims for moral damages, exemplary damages, attorney's fees plus appearance fees, and expenses of litigation. Subsequently, respondent filed a Second Amended Complaint with Preliminary Attachment dated 25 October 1991.19 The amendment introduced dealt solely with the number of postdated checks issued by petitioner as full payment for the first cylinder liner it ordered from respondent. Whereas in the first amended complaint, only nine postdated checks were involved, in its second amended complaint, respondent claimed that petitioner actually issued ten postdated checks. Despite the opposition by petitioner, the trial court admitted respondent's Second Amended Complaint with Preliminary Attachment.20 Prior to the commencement of trial, petitioner filed a Motion (For Leave To Sell Cylinder Liners)21 alleging therein that "[w]ith the passage of time and with no definite end in sight to the present litigation, the cylinder liners run the risk of obsolescence and deterioration"22 to the prejudice of the parties to this case. Thus, petitioner prayed that it be allowed to sell the cylinder liners at the best possible price and to place the proceeds of said sale in escrow. This motion, unopposed by respondent, was granted by the trial court through the Order of 17 March 1991.23 After trial, the court a quo dismissed the action, the decretal portion of the Decision stating: WHEREFORE, the complaint is hereby dismissed, with costs against the plaintiff, which is ordered to pay P50,000.00 to the defendant as and by way of attorney's fees. 24 The trial court held respondent bound to the quotation it submitted to petitioner particularly with respect to the terms of payment and delivery of the cylinder liners. It also declared that respondent had agreed to the cancellation of the contract of sale when it returned the postdated checks issued by petitioner. Respondent's counterclaims for moral, exemplary, and compensatory damages were dismissed for insufficiency of evidence. Respondent moved for the reconsideration of the trial court's Decision but the motion was denied for lack of merit.25 Aggrieved by the findings of the trial court, respondent filed an appeal with the Court of Appeals26 which reversed and set aside the Decision of the court a quo. The appellate court brushed aside petitioner's claim that time was of the essence in the contract of sale between the parties herein considering the fact that a significant period of time had lapsed between respondent's offer and the issuance by petitioner of its purchase orders. The dispositive portion of the Decision of the appellate court states:

WHEREFORE, the decision of the lower court is REVERSED and SET ASIDE. The appellee is hereby ORDERED to pay the appellant the amount of P954,000.00, and accrued interest computed at 14% per annum reckoned from May, 1991.27 The Court of Appeals also held that respondent could not have incurred delay in the delivery of cylinder liners as no demand, judicial or extrajudicial, was made by respondent upon petitioner in contravention of the express provision of Article 1169 of the Civil Code which provides: Those obliged to deliver or to do something incur in delay from the time the obligee judicially or extrajudicially demands from them the fulfillment of their obligation. Likewise, the appellate court concluded that there was no evidence of the alleged cancellation of orders by petitioner and that the delivery of the cylinder liners on 20 April 1990 was reasonable under the circumstances. On 22 May 2000, petitioner filed a motion for reconsideration of the Decision of the Court of Appeals but this was denied through the resolution of 06 October 2000.28 Hence, this petition for review which basically raises the issues of whether or not respondent incurred delay in performing its obligation under the contract of sale and whether or not said contract was validly rescinded by petitioner. That a contract of sale was entered into by the parties is not disputed. Petitioner, however, maintains that its obligation to pay fully the purchase price was extinguished because the adverted contract was validly terminated due to respondent's failure to deliver the cylinder liners within the two-month period stated in the formal quotation dated 31 May 1989. The threshold question, then, is: Was there late delivery of the subjects of the contract of sale to justify petitioner to disregard the terms of the contract considering that time was of the essence thereof? In determining whether time is of the essence in a contract, the ultimate criterion is the actual or apparent intention of the parties and before time may be so regarded by a court, there must be a sufficient manifestation, either in the contract itself or the surrounding circumstances of that intention.29 Petitioner insists that although its purchase orders did not specify the dates when the cylinder liners were supposed to be delivered, nevertheless, respondent should abide by the term of delivery appearing on the quotation it submitted to petitioner.30 Petitioner theorizes that the quotation embodied the offer from respondent while the purchase order represented its (petitioner's) acceptance of the proposed terms of the contract of sale.31 Thus, petitioner is of the view that these two documents "cannot be taken separately as if there were two distinct contracts."32 We do not agree. It is a cardinal rule in interpretation of contracts that if the terms thereof are clear and leave no doubt as to the intention of the contracting parties, the literal meaning shall control.33 However, in order to ascertain the intention of the parties, their

contemporaneous and subsequent acts should be considered.34 While this Court recognizes the principle that contracts are respected as the law between the contracting parties, this principle is tempered by the rule that the intention of the parties is primordial35 and "once the intention of the parties has been ascertained, that element is deemed as an integral part of the contract as though it has been originally expressed in unequivocal terms."36 In the present case, we cannot subscribe to the position of petitioner that the documents, by themselves, embody the terms of the sale of the cylinder liners. One can easily glean the significant differences in the terms as stated in the formal quotation and Purchase Order No. 13839 with regard to the due date of the down payment for the first cylinder liner and the date of its delivery as well as Purchase Order No. 14011 with respect to the date of delivery of the second cylinder liner. While the quotation provided by respondent evidently stated that the cylinder liners were supposed to be delivered within two months from receipt of the firm order of petitioner and that the 25% down payment was due upon the cylinder liners' delivery, the purchase orders prepared by petitioner clearly omitted these significant items. The petitioner's Purchase Order No. 13839 made no mention at all of the due dates of delivery of the first cylinder liner and of the payment of 25% down payment. Its Purchase Order No. 14011 likewise did not indicate the due date of delivery of the second cylinder liner. In the case of Bugatti v. Court of Appeals,37 we reiterated the principle that "[a] contract undergoes three distinct stages preparation or negotiation, its perfection, and finally, its consummation. Negotiation begins from the time the prospective contracting parties manifest their interest in the contract and ends at the moment of agreement of the parties. The perfection or birth of the contract takes place when the parties agree upon the essential elements of the contract. The last stage is the consummation of the contract wherein the parties fulfill or perform the terms agreed upon in the contract, culminating in the extinguishment thereof." In the instant case, the formal quotation provided by respondent represented the negotiation phase of the subject contract of sale between the parties. As of that time, the parties had not yet reached an agreement as regards the terms and conditions of the contract of sale of the cylinder liners. Petitioner could very well have ignored the offer or tendered a counter-offer to respondent while the latter could have, under the pertinent provision of the Civil Code,38 withdrawn or modified the same. The parties were at liberty to discuss the provisions of the contract of sale prior to its perfection. In this connection, we turn to the testimonies of Pajarillo and Kanaan, Jr., that the terms of the offer were, indeed, renegotiated prior to the issuance of Purchase Order No. 13839. During the hearing of the case on 28 January 1993, Pajarillo testified as follows: Q: You testified Mr. Witness, that you submitted a quotation with defendant Lorenzo Shipping Corporation dated rather marked as Exhibit A stating the terms of payment and delivery of the cylinder liner, did you not? A: Yes sir.

Q: I am showing to you the quotation which is marked as Exhibit A there appears in the quotation that the delivery of the cylinder liner will be made in two months' time from the time you received the confirmation of the order. Is that correct? A: Yes sir. Q: Now, after you made the formal quotation which is Exhibit A how long a time did the defendant make a confirmation of the order? A: After six months. Q: And this is contained in the purchase order given to you by Lorenzo Shipping Corporation? A: Yes sir. Q: Now, in the purchase order dated November 2, 1989 there appears only the date the terms of payment which you required of them of 25% down payment, now, it is stated in the purchase order the date of delivery, will you explain to the court why the date of delivery of the cylinder liner was not mentioned in the purchase order which is the contract between you and Lorenzo Shipping Corporation? A: When Lorenzo Shipping Corporation inquired from us for that cylinder liner, we have inquired [with] our supplier in Japan to give us the price and delivery of that item. When we received that quotation from our supplier it is stated there that they can deliver within two months but we have to get our confirmed order within June. Q: But were you able to confirm the order from your Japanese supplier on June of that year? A: No sir. Q: Why? Will you tell the court why you were not able to confirm your order with your Japanese supplier? A: Because Lorenzo Shipping Corporation did not give us the purchase order for that cylinder liner. Q: And it was only on November 2, 1989 when they gave you the purchase order? A: Yes sir. Q: So upon receipt of the purchase order from Lorenzo Shipping Lines in 1989 did you confirm the order with your Japanese supplier after receiving the purchase order dated November 2, 1989? A: Only when Lorenzo Shipping Corporation will give us the down payment of 25%.39

For his part, during the cross-examination conducted by counsel for petitioner, Kanaan, Jr., testified in the following manner: WITNESS: This term said 25% upon delivery. Subsequently, in the final contract, what was agreed upon by both parties was 25% down payment. Q: When? A: Upon confirmation of the order. ... Q: And when was the down payment supposed to be paid? A: It was not stated when we were supposed to receive that. Normally, we expect to receive at the earliest possible time. Again, that would depend on the customers. Even after receipt of the purchase order which was what happened here, they re-negotiated the terms and sometimes we do accept that. Q: Was there a re-negotiation of this term? A: This offer, yes. We offered a final requirement of 25% down payment upon delivery. Q: What was the re-negotiated term? A: 25% down payment Q: To be paid when? A: Supposed to be paid upon order.40 The above declarations remain unassailed. Other than its bare assertion that the subject contracts of sale did not undergo further renegotiation, petitioner failed to proffer sufficient evidence to refute the above testimonies of Pajarillo and Kanaan, Jr. Notably, petitioner was the one who caused the preparation of Purchase Orders No. 13839 and No. 14011 yet it utterly failed to adduce any justification as to why said documents contained terms which are at variance with those stated in the quotation provided by respondent. The only plausible reason for such failure on the part of petitioner is that the parties had, in fact, renegotiated the proposed terms of the contract of sale. Moreover, as the obscurity in the terms of the contract between respondent and petitioner was caused by the latter when it omitted the date of delivery of the cylinder liners in the purchase orders and varied the term with respect to the due date of the down payment,41 said obscurity must be resolved against it.42 Relative to the above discussion, we find the case of Smith, Bell & Co., Ltd. v. Matti,43 instructive. There, we held that When the time of delivery is not fixed or is stated in general and indefinite terms, time is not of the essence of the contract. . . .