Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

In Lighter Vein

Hochgeladen von

Nikhil SinghOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

In Lighter Vein

Hochgeladen von

Nikhil SinghCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

IN LIGHTER VEIN RELAX, LAUGH AND ENJOY LEARNING THROUGH HUMOUR AND HUMOUR IN LEARNING (S. KRISHNAMURTHY, B.Com.

, F.C.A., VISITING FACULTY: IIM -B) WELCOME TO THE SESSIONS WHICH I AM SLATED TO HANDLE. The subjects I handle are highly sedative in nature . Try and read through the notes and the text books involved, deep sleep is guaranteed. Best cure for insomniacs! LEARNING is an activity requiring concentration and memory. These are not possible under tension and pressure. Unfortunately, we are of ten compelled to learn under these very conditions. This results in fatigue and boredom. I happen to teach in several Schools (Institute) of Management. Almost all these schools order Put the students under pressure and then only they will lear n. This is in direct contradiction to the very meaning of the School as a place of learning. The word SCHOOL originated from the Greek word SKHOLE meaning leisure. Schools became the places of learning because they were places where people could relax. You learn only when you relax. Humour is one of the best ways to relax. Hence combination of humour with learning makes learning enjoyable, informal and memorable. If you delve into the origin of certain words associated with business, you find they

have very interesting and humorous origin. Enclosed are a few such words and why we use them to mean what they mean. These are from WHY YOU SAY IT by Webb B. Garrison (Abingdon Press) pp 448 $3l95 Edn.1952. I have added a few more to this with s ource reference where ever they are available. Peruse them, laugh and relax. Yours in laughter,

IN LIGHTER VEIN RELAX, LAUGH AND ENJOY

Ledger At a period when most institutions were complacent about the ignorance of the period now called the Dark Ages, the church was the one guardian of learning. Though all books had to be written by hand, they were manufactured in a surprising number and variety. One of the most important was the large breviary used in public services. Strict regulations forbade the removal of this book from the place of worship. So it was called a lidger, from Old English dialect liggen (to lie). In 1500 the term was being applied to any book which lay permanently in one place. Early in the century curates were asked to provide a booke of the bible in Englishe, of the largest volume, to be a lidger in the same church for the parishioners to read on. Soon the name became attached to important volumes of all sorts, including the record books of merchants. Its ties with the church severed, ledger soon became obsolete except in the commercial world. Commission At the height of her glory imperial Rome dominated dozens of formerly independent kingdoms. Treaties and pacts were constantly being drawn up and sent to the far corners of the world for approval by some prince. The messenger carrying a royal document was said to bear a commission, from a term for entrusted. Passing through Old French, the term became current in English about a century before the time of Columbus. It long designated pay for services as an agent. Thus, a diplomatic messenger was listed on the payroll as a commissioner. Commission was usually on an agreed salary basis and was paid such diverse agents as tax collectors, sea captains, and wandering

tradesmen. As late as the eighteenth century Daniel Defoe , author of Robinson Crusoe, used commission in about the same sense we now use wages. But the commercial world gradually adopted a faster pace. Merchants discovered that a sea captain was likely to be commissioner for half a dozen rivals as well as for his chief employer. Someone thought of offering the commissioner a percentage of profits rather than a flat fee. This type of inducement proved so effective that modern commission systems came into being. Discount Tradesmen apparently began using the premium technique quite early in modern times. There is evidence that Italians were first to knock off stated prices in bargaining. French adopted the custom by 1500 and, influenced by Italian slang, called it descomple (taken from the count). Apparently the practice consisted of selling merchandise by count, setting aside a portion of a lot when computing its cost. Jumping the English Channel and emerging into the new tongue as discount, the premium in goods was abandoned in favour of reduction in price. As early as 1622 English merchants offered a discount on pepper sold in Holland. selling. Bonus Most common words can be traced to a definite point of origin. An important exception is bonus. Scholars guess that it came into use in the first half of the seventeenth century as a pun on classical Latin bonum (a good thing). At best, however, this is only a reasonable conjecture. Who coined the word and when, no one knows. In its first recorded use, about 1770, a bonus referred to a political plum. Corruption was widespread in English politics of the era, and pork-barrel operations were extensive. Many an officeholder received some extra-or bonus-which taxpayers never intended him to get. Its popularity spreading, the practice became so general that it became a standard device in modern

Financial leaders eventually borrowed the old term and applied it to any type of premium. Typical usage was that of the Edinburgh Review, which 1802 discussed a bonus of % interest. Though neither good Latin nor genuine English, the hybrid term proved so useful that it became standard in the business world. Account Caravans and trading vessels made international business an important factor in the economic life of ancient Rome. Some of her merchants accumulated large fortunes; many found it necessary to employ bookkeepers to keep track of transactions. Their customers in Gaul used aconl, from compulare (to count), to designate any completed process of counting goods or money. Through Norman followers of William the Conqueror this business term entered Old English before the thirteenth century. It was long used to signify any type of reckoning from counting money to surveying land or computing the position of a ship. Business gradually came into more and more prominence, and credit systems were expanded. This made it necessary for merchants to make a periodic account of each person with whom they dealt. Hence, study of accounting came into prominence. Much later, no less a dignitary than Benjamin Franklin recorded that, as a young man, he attended the business diligently, studied accounts, and grew expert as selling. Expansion of modern sales methods has given one more twist to the ancient word. For convenience it is now commonplace to refer to a regular customer as an account. So recent is this development that it is not yet accepted as good usage, and dictionary makers do not even list it. Contract By combining con (with) and trahere (to draw), Roman diplomats formed the word contractus (drawn together). They used it in a special sense, to designate the

condition of harmony and bliss that marked a political unit drawn together with Rome in a treaty. It made no difference, of course, whether the union was voluntary or enforced! Both the practice and its name were handed down to other peoples. Chaucers famous Canterbury Tales, landmark of early English literature, includes mention of a political contract. Later expansion of commerce made it desirable for businessmen to enter legal treaties with one another. Naturally, the name of the old political pact passed to the commercial agreement. Pushed into prominence by complex and large-scale operations in spice, cotton, and other commodities, the contract was a standard business device by 1575. Retail Peasants of medieval France, influenced by Latin talea (twig) used tail to designate the process of splitting logs into sections small enough in handle. This was heavy work, and axmen carried tail no farther than absolutely necessary. Frequently they delivered wood to dealers in chunks too big for use in the fireplace. Before passing it on to his customers, he had to retail such pieces, or cut them into several small sections. In similar fashion the spice dealer had to re-tail barrels of cloves, and the wool merchant had to re-cut bales of lint. This activity was so characteristic that it came to describe the work of any small merchant. By the fourteenth century, whether re-cutting was involved or not, the broken-lot tradesman was known as a retail dealer. Fee Until modern times every form of business transaction was closely linked to the soil. Money, as we know it, was a device limited to the use of highly civilized peoples. Among those who were predominantly rural, all obligations were met by payments of farm products. Much commerce was carried on by means of barter, or exchange.

Since cattle were both valuable and easy to take from place to place, in AngloSaxon Britain they were the chief means of making payments. In the language of the day the animals were called feoh. It was used so widely that it came to stand for all charges which public officials and professional men exacted from citizens. Slightly modified in spelling the term became fee which must still be placed in the hand of the lawyer, the doctor, and the sheriff. Salary In ancient times salt was both scarce and expensive. Hence, Roman soldiers demanded a special form of payment for purchase of salt. Some of the famous highways of the time were built for the sole purpose of transporting salt to cities. One such road was even named Vin Salarium. Salt money doled out to soldiers was called simply salarium. So when the English-speaking world needed a term so mean regular pay, the old Roman word for salt money was altered slightly. As a result we have the very important word salary. Finance Romances about medieval life usually depict all the glamour but omit less pleasant details. Few kingdoms levied taxes in the modern form, but sovereigns collected tribute and ransom at the slightest excuse. Often large enough to be burdensome, such fines had to be paid within a stipulated time. Even men of wealth frequently had to pay by the installment plan; it was a great accomplishment to bring ones indebtedness to an end. Any method of ending an obligation was called finance, from Old French finer (to end). Widely used in the sense of modern ransom, the term eventually came to stand for management of monetary affairs.

Budget Struggling with a budget is no new problem; it dates back to the days of the Roman Empire. Latin housewives seldom had a regular amount given them by their husbands each week or month. Consequently, they were forced to be very cautious in their spending. This led to the practice of keeping money for household expenses in little leather bags, each holding a sum set aside for a specific item. This custom also prevailed among businessmen, who may have borrowed it from their wives or vice versa. Bulga, the Latin word for bag, became attached to careful planning of ones finances. Adopted into French as bougette, it eventually entered English as budget. Franchise Few people of early western Europe were so fierce or so proud as the savage Franks. They were so stubborn in fighting for freedom that their very name came to be identified with liberty as it was then interpreted. It became standard usage so distinguish between slaves and free men by terming the latter franc. Modified to franchise the term came to signify any type of legal immunity, such as a towns franchise by which its merchants sold salt without paying royal taxes. It is this sort of usage which still survives in the franking privilege which permits congressmen to mail official letters without postage. As early as 1350 the franchise expanded from mere legal immunity to include any type of special privilege conferred by a sovereign. Two centuries later Sir Francis Drake applied for a franchise when he wished permission to explore the New World. Early U.S. land companies adopted the old term, and popular usage later linked it with rights conferred upon utility companies, railroads, and other public-service

corporations. Then the development of patents and brand-name merchandising created a new job for the Old World word. Unchanged in spelling, franchise came into new prominence to stand for an agent's privilege to represent a particular manufacturer in a given territory. European rulers of the late Middle Ages had dictorial power over practically every area of life. If a sovereign wished, he could grant one of his favorites a vast tract of land, a title, or even the right to a monopoly in some type of trade. Such privileges were commonly listed in an official document which the owner could exhibit in order to prove his claims. To distinguish papers of this sort from such secret transactions as treaties, they were called lettres patents (open letters). Abbreviated to patent, the royal grant was later attached to products of inventive genius. Among the first of modern patents was a secret formula for making leather waterproof by means of a shiny black varnish. Varieties of this "patent-treated leather" were in use as early as 1800. It proved so popular that the name was clipped to patent and applied not only to varnished leather but also to manufactured fabrics of similar appearance. Gazette Long popular as a name for newspapers, gazette is now loosely used to stand for papers in general. On the surface it does not betray its relationship to the family of money words but seems naturally to belong to the field of communication. Actually the newspaper term takes its name from an obscure Venetian coin. Issued for use in foreign trade, the gazette varied in value from less than a farthing (1/2 cent) to about three farthings. It was in use for at least three centuries. About 1550 a Venetian publisher brought out one of the earliest of newspapers. He either sold copies for one gazette or charged that sum for the privilege of reading it. Most scholars favor the latter view. At any rate the paper came to be associated with the coin paid by the reader and was itself popularly called "the gazette". Adopted by English journalists, the coin-named sheet became known as a gazette.

Broker French-speaking Normans of medieval times were noted for their wines and capacity to consume them. Even a veteran brewer never quite knew how a particular brew would turn out, however. So it was an occasion of no small importance when the tavern keeper rolled out a new barrel, turned it on end, and drove in a broche- or spigot. From the importance of the little device the man who used it came to be called a brocheur. Many a village had no businessman, in the modern sense, other than the brocheur at the inn. He seldom produced his own stock in trade but bought in quantity from brewers and sold by mug or horn. So important was the role of the tapster that, modified to broker, his name attached to any agent or professional in the business of buying and selling. Long applied to retain merchants, this early usage is preserved in the name of the pawnbroker. With the rise of bulk commerce some middlemen began to specialize in such commodities as tea, salt, indigo, and wood. Modern financial methods, coupled with the Industrial Revolution, created an opportunity for the broker to engage in large-scale operations and standardize his methods. Fiscal A simple little basket made of reeds was the usual device for transporting coins between Roman business houses. Such a basket was called a fiscus, from the Latin term "rush." Eventually the public treasury was developed. Its connection with the fiscus led to its being known as the fise. This usage passed through Old French into English. By the sixteenth century any transaction related to public funds (as opposed to ecclesiastical) was known as a fiscal operation.

LANGUAGE A German student learning English was reading the Bible. He had to be explained the meaning of "Mary was great with child". He understood the explanation. Half an hour later he came back and asked with a puzzled expression "What does it mean "Mr.Smith was great with children?" MEMORY I write down everything I want to remember. That way, instead of spending a lot of time trying to remember what I wrote down, I spend my time trying to locate the paper I wrote them down. EFFORT "Is it hard to paint a picture?" "Not at all! It is either easy or impossible." FREEDOM Who ever says "There is no freedom of speech in dictatorship?" They are wrong. There is Freedom of Speech everywhere. The only difference is that in democracy there is freedom after the speech also. SIGN ON THE EXECUTIVE'S DESK Make one person happy every day Namely me. Come to me with any problem. I will add to it. Economy is in itself a source of great revenue. Both my ears are open always with a connecting hole to the other.

TAXES All of us want to be honest. We would like to pay our taxes with smile. But government wants it in cash. IDEAL HUSBAND One who does not tell his wife everything on the premise that what she doesn't know will not hurt him. EXPERIENCE 20 years of experience doesn't mean anything if it is 20 years of committing the same mistake.

MISTAKE IN HASTE I am always dumb to kind animals. BUDGET In a majic-show, do not watch the majician's face or listen to his words. Instead watch his hands. In a budget speech, do not listen to the minister and read his speech. Instead, read the Notifications. DELEGATION You can delegate the work of preparation of coffee. But you cannot delegate drinking of the same. COMPLEXITY OF LAW: "When two railroad trains meet at a crossing, each shall stop and neither shall proceed until the other has passed" Railroad legislation in Waco, Texas, USA in the middle of 19th Century. "The driver of any vehicle involved in an accident resulting in death, shall immediately stop and give his name and address to the person struck" Oklahoma State Law on Motor Accidents. ". And a body corporate shall not be deemed, for the purpose of this section, to cease to be Resident in the United Kingdom by reason only that it ceases to exist" 1951 U.K. Finance Act Section 36(10) "No dog shall be in a public place without its master on a leash" Ordnance No.6 of Arvada, Colorado, USA "If a stray dog is not claimed within 25 hours, the owner will be destroyed" Para 15 of the above Ordnance.

(The above are from "SOD'S LAWS" by Richard De'ath: Universal Law Publishing, 1998 First Indian Edn ISBN 81-7534-098-3) I discovered that no law in that country may be longer than the number of letters in the alphabet and must be written simply so all will easily understand it" Gulliver's Travel by Jonathan Swift. HUMAN BRAIN CAN CONCENTRATE CONTINUOUSLY ONLY FOR 80 SECONDS AT A TIME. ONE CAN NORMALLY READ ONLY 26 WORDS (ENGLISH) WITHIN THIS TIME AND UNDERSTAND THE SAME. ANYTHING LONGER REQUIRES ANOTHER READING

Anon, Psycologists' finding as to why Readers' Digest is the most read magazine in the world (Average number of words in a sentence is only 21 in Reader's Digest) "In the Nuts (unground, other than ground nuts) Order, the expression "nuts" shall have reference to such nuts, as would, but for this Amending Order, not qualify as "nuts" (unground, other than ground nuts) by reason of their being nuts (unground)" Scottish Law Ref. Guinness Book of World Records.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Sl. No. Statement Right Wrong Remarks: Visiting Faculty: IIM-B & Director Business Systems SIE WTODokument4 SeitenSl. No. Statement Right Wrong Remarks: Visiting Faculty: IIM-B & Director Business Systems SIE WTONikhil SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Query Sheet 0808Dokument1 SeiteQuery Sheet 0808Nikhil SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pub 653 CDROM TextDokument48 SeitenPub 653 CDROM TextNikhil SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pot - Oni ForexDokument19 SeitenPot - Oni ForexNikhil SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Note 3-Brief On MCCDokument17 SeitenNote 3-Brief On MCCNikhil SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Note 2 Ind - LawsDokument5 SeitenNote 2 Ind - LawsNikhil SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Note 1 Overview MCCDokument5 SeitenNote 1 Overview MCCNikhil SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Icc Force Majeure NewDokument15 SeitenIcc Force Majeure NewNikhil SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5795)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Mathsnacks05 InfiniteDokument1 SeiteMathsnacks05 Infiniteburkard.polsterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eternal LifeDokument9 SeitenEternal LifeEcheverry MartínNoch keine Bewertungen

- Feline Neonatal IsoerythrolysisDokument18 SeitenFeline Neonatal IsoerythrolysisPaunas JoshiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Best-First SearchDokument2 SeitenBest-First Searchgabby209Noch keine Bewertungen

- Zero Power Factor Method or Potier MethodDokument1 SeiteZero Power Factor Method or Potier MethodMarkAlumbroTrangiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ZKAccess3.5 Security System User Manual V3.0 PDFDokument97 SeitenZKAccess3.5 Security System User Manual V3.0 PDFJean Marie Vianney Uwizeye100% (2)

- Is 13779 1999 PDFDokument46 SeitenIs 13779 1999 PDFchandranmuthuswamyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 3 The Prodigal SonDokument2 SeitenLesson 3 The Prodigal Sonapi-241115908Noch keine Bewertungen

- Hedonic Calculus Essay - Year 9 EthicsDokument3 SeitenHedonic Calculus Essay - Year 9 EthicsEllie CarterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Islamic Meditation (Full) PDFDokument10 SeitenIslamic Meditation (Full) PDFIslamicfaith Introspection0% (1)

- Enunciado de La Pregunta: Finalizado Se Puntúa 1.00 Sobre 1.00Dokument9 SeitenEnunciado de La Pregunta: Finalizado Se Puntúa 1.00 Sobre 1.00Samuel MojicaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Need You Now Lyrics: Charles Scott, HillaryDokument3 SeitenNeed You Now Lyrics: Charles Scott, HillaryAl UsadNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Guide To Effective Project ManagementDokument102 SeitenA Guide To Effective Project ManagementThanveerNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Terrifying ExperienceDokument1 SeiteA Terrifying ExperienceHamshavathini YohoratnamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complete PDFDokument495 SeitenComplete PDFMárcio MoscosoNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is Folate WPS OfficeDokument4 SeitenWhat Is Folate WPS OfficeMerly Grael LigligenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Problem ManagementDokument33 SeitenProblem Managementdhirajsatyam98982285Noch keine Bewertungen

- Writing - Hidden Curriculum v2 EditedDokument6 SeitenWriting - Hidden Curriculum v2 EditedwhighfilNoch keine Bewertungen

- 9m.2-L.5@i Have A Dream & Literary DevicesDokument2 Seiten9m.2-L.5@i Have A Dream & Literary DevicesMaria BuizonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Syllabus/Course Specifics - Fall 2009: TLT 480: Curricular Design and InnovationDokument12 SeitenSyllabus/Course Specifics - Fall 2009: TLT 480: Curricular Design and InnovationJonel BarrugaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Study of Consumer Behavior in Real Estate Sector: Inderpreet SinghDokument17 SeitenA Study of Consumer Behavior in Real Estate Sector: Inderpreet SinghMahesh KhadeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Core ApiDokument27 SeitenCore ApiAnderson Soares AraujoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mezbah Uddin Ahmed (173-017-054) Chapter 11Dokument12 SeitenMezbah Uddin Ahmed (173-017-054) Chapter 11riftNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conrail Case QuestionsDokument1 SeiteConrail Case QuestionsPiraterija100% (1)

- Validator in JSFDokument5 SeitenValidator in JSFvinh_kakaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Del Monte Usa Vs CaDokument3 SeitenDel Monte Usa Vs CaChe Poblete CardenasNoch keine Bewertungen

- ID2b8b72671-2013 Apush Exam Answer KeyDokument2 SeitenID2b8b72671-2013 Apush Exam Answer KeyAnonymous ajlhvocNoch keine Bewertungen

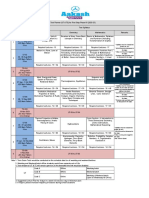

- UT & TE Planner - AY 2023-24 - Phase-01Dokument1 SeiteUT & TE Planner - AY 2023-24 - Phase-01Atharv KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing Care Plan: Pt.'s Data Nursing Diagnosis GoalsDokument1 SeiteNursing Care Plan: Pt.'s Data Nursing Diagnosis GoalsKiran Ali100% (3)

- Ghalib TimelineDokument2 SeitenGhalib Timelinemaryam-69Noch keine Bewertungen