Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook#1

Hochgeladen von

Timothy CurtisCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook#1

Hochgeladen von

Timothy CurtisCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

University of Northampton

Enterprising Communities

Social Innovation Workbook

Tim Curtis. Alison Bell. Amy Bowkett 11/30/2012

SWK1048 Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook

Contents

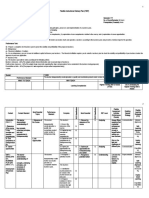

UNIT 1 Introduction to Social Enterprise .................................................................................................. 3 What is social enterprise for? ............................................................................................................... 3 Social Entrepreneurship ....................................................................................................................... 9 Effectuation .................................................................................................................................... 10 Social Enterprise ............................................................................................................................. 11 Social justice ................................................................................................................................... 13 Unit 2: Understanding me- my personal assets, skills and resources and my innovation orientation .. 15 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 15 Social capital ....................................................................................................................................... 15 Developing Social Capital ................................................................................................................... 16 UNIT 3 Creativity and innovation ........................................................................................................... 18 The Rules of Brainstorming ................................................................................................................ 22 Inspiration ........................................................................................................................................ 24 Unit 4 Social Problems and Opportunities ............................................................................................. 25 Problems as opportunities ................................................................................................................. 26 African innovations ............................................................................................................................. 28 Triggers and inspirations that prompt innovation.............................................................................. 29 Thinking differently ............................................................................................................................ 30 Selecting problems ............................................................................................................................. 31 Understanding how root causes work ................................................................................................ 31 Analysing complex situations ............................................................................................................. 33 WICKED PROBLEMS ........................................................................................................................ 34 What is a rich picture? .................................................................................................................... 38 How to create your rich picture ..................................................................................................... 39 Unit 5 Venture Organising ...................................................................................................................... 42 Setting Objectives and outcomes ....................................................................................................... 42 Parts of Evaluation .............................................................................................................................. 42 Goals ............................................................................................................................................... 42 Objectives ....................................................................................................................................... 42 Outcome Objectives (Final/Intermediate)...................................................................................... 43 Process Objectives .......................................................................................................................... 43 Logic Models for Objective setting ..................................................................................................... 45 The What: How to Read a Logic Model ....................................................................................... 46 The WHY: Logic Model Purpose and Practical Application ............................................................. 46 If only it was as simple as this. ......................................................................................................... 46 1|P a g e

SWK1048 Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook

Premortems .................................................................................................................................... 47 Showing progress ............................................................................................................................... 48 Theory of change model ..................................................................................................................... 49 Business Model Canvas ...................................................................................................................... 51 Fundamental Models of Social Enterprise Strategy ........................................................................... 55 Entrepreneur Support Model ......................................................................................................... 55 Market Intermediary Model ........................................................................................................... 55 Employment Model ........................................................................................................................ 55 Fee-for-Service Model .................................................................................................................... 55 Low-Income Client as Market Model ............................................................................................. 56 Cooperative Model ......................................................................................................................... 56 Market Linkage Model .................................................................................................................... 56 Service Subsidy Model .................................................................................................................... 57 Organizational Support Model ....................................................................................................... 57 Combining Models .......................................................................................................................... 57 Complex Model .............................................................................................................................. 58 Mixed Model .................................................................................................................................. 58 Legal Frameworks ............................................................................................................................... 59 Common legal structures ............................................................................................................... 59 Choosing the appropriate legal structure ....................................................................................... 63

This workbook is primarily designed as additional reading and work outside class. It should be used in addition to the activities and exercises in class. The activities in class complement this workbook, and all of the workbook, and the class activities are relevant for your assignment.

Draft #1

2|P a g e

SWK1048 Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook

If I had 60 minutes to solve a problem and my life depended on it, Id spend 55 minutes determining the right question to ask, and 5 minutes thinking aloud about the solution. Albert Einstein

UNIT 1 Introduction to Social Enterprise

The starting point for the study of any topic is often to provide a definition, defining the key terms that we are studying. We have a problem with social enterprise as a term, however, because there is still a lot of debate about a definition. We will come back to definitions in a while, but first I was to ask a slightly different question.

What is social enterprise for?

This, I think is a better question than what is social enterprise. I think that the question makes our study of social enterprise purposeful. It seems to me that social enterprise the PURPOSE of social enterprise is making the world a slightly better place. But there are lots of different ways of making the world a better place and this can just get messy and confusing. We need a way of sorting out what types of social change there are, and which type of social change social enterprise fits into. There are a least three types of activity we could use to make the world a better place. We could: Change the law Create a new product Volunteer.

EXERCISE 1:

Think of three changes in the law that have changed the way in which the world worked.

Did you think of: The emancipation of women or African-Americans to get the vote? The creation of public health and education systems through government finances?

How the world is made better by these actions?

EXERCISE 2:

Think of three products that have fundamentally changed the world for better.

3|P a g e

SWK1048 Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook

Did you think of: The vacuum cleaner and how it freed women (and servants) from constant house cleaning to be able to work and act as a consumer? The wind up radio and how it made public radio globally available really cheaply and with the need for access to mains electricity or expensive and environmentally damaging batteries? The mobile phone and how it has made communications in Africa very easy, allowing people to check whether a doctor is actually at a surgery before setting off on a long walk, or how Africans can now safely transfer money to each other entirely by mobile phone without the need for bank accounts?

These three different ways of changing the world can be categorised into three circles or domains of activity. Maths experts amongst you will recognise this diagram as a Venn diagram:

How do we make the world a better place?

Change the law Public Sector Private Sector Invent a great product

Civil Society

Volunteer

FIGURE 1 A VENN DIAGRAM ABOUT HOW DIFFERENT SECTORS CHANGE THE WORLD .

If we give generic names to our changing the law, inventing a great product or volunteering activities, we can come up with different sectors called Public, Private and Civil (or community). Typically, these sectors have been considered to be entirely separate. The government has always done government type things like making laws and providing health and education services (for example) and the private sector always gets on with doing business. Over the last twenty years or so, this separation seems to have reduced, to the point of overlapping. It is this overlap that seems to be the domain of action for social enterprise. Commentators like Charles Leadbeater, who began writing about this under the guise of the social market in the late 1980s and became an advisor to the New Labour government in 1997, also thought that this overlapping model was important when he was trying to describe the social entrepreneur in 1997.

4|P a g e

SWK1048 Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook

Source: Leadbeater, C. (1997), The Rise of the Social Entrepreneur, London: Demos, p. 10

FIGURE 2 O VERLAPPING WAYS TO CHANGE THE WORLD

This way of thinking about the different types of social change is actually quite widespread. Colleagues in other universities have spend time with people who are called social entrepreneurs asking them to explain what social enterprise is, and they consistently come up with the same model in their head. Figure 3 shows an example of their research taking from scribbles on bits of paper and tablecloths in cafes as those running social enterprises struggle to explain the idea.

Seanor, P., Bull, M. & Ridley-Duff, R. J. (2007) "Contradictions in Social Enterprise: Do they draw in straight lines or circles?" FIGURE 3 M ENTAL MODELS OF SOCIAL ENTERPRISE Glasgow, 7-9th November, Drawings 8 and 10 paper to 30th ISBE Conference,

If we keep on thinking about this sectors approach we can think of types of social change that might happen in the parts of the Venn diagram that overlap with each other. Public/Private overlap Since the 1980s in the UK, government agencies have been increasingly contracting private companies to provide public services. Most of the time this is a straightforward business activity like supplying photocopies or mobile phones, but it also increasingly involves delivering public services under contract to a government agency. This has involves a debate (a contestation) between a public 5|P a g e

SWK1048 Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook

service ethos and a business efficiency mentality. Commentators called the influence of business and 1 market dynamics on the public sector New public management . On the other hand, public service ethos has pushed back into the space with businesses being established that operate with a high service ethic. Public/Voluntary overlap The voluntary sector provided publicly valuable services long before the growth of the welfare state (which started emerging in Germany in the 1870s and in Britain in the 1930s). Religious groups, communities, families and individuals have provided social care and poverty relief for centuries. By 1939 in the UK, the vast network of friendly societies and industrial and provident societies institutions run by local councils were nationalised into a single and (in theory) nationally consistent system. This didnt mean the end of the voluntary sector- there is still much that the state cannot do, or cannot afford to do. There are many issues that are just not considered important enough for governments to provide, and these fall to voluntary sector organisations. By the 1980s however, government departments, particularly local authorities were given the opportunity to provide funds to voluntary sector organisations, first through open and flexible service level agreements and then through competitive tendering and contracting processes. This has meant that some charities have increased the amount of work that they do under contract to the government. This has increased, 2 overall, from 4% of income to 12% of income in the last 12 years , whilst donations and other income has stayed more or less the same. Private/voluntary overlap Philanthropy, in its modern usage, is the giving of spare money, time or resources from a business to voluntary good cause. Some very wealthy people give away very large amounts of money- Warren Buffet, an American businessman has committed to give 99% of his personal US$ 46 billion away to charities, mostly to the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation for healthcare projects around the world. Other companies engage in Corporate Social Responsibility activities. These CSR activities are projects and initiatives that help communities but are not directly related to the core purpose of the company. These activities are concerned with developing good relationships with stakeholders, people who have a stake in the good behaviour of a company, which is different from shareholders, who own and receive a portion of the profits of a company. This has shifted as more voluntary organisations have begun trading as part of their charitable objectives. An obvious example is a charity clothes shop. People donate their spare clothes for free, and the charity shop sells them for a modest price to raise money for other activities. This isnt the same as the government contract, because the person spending the money in the charity shop is a retail customer rather than a commissioner of services. Right in the middle In the centre of the diagram, when the Venn diagram circles get close enough, is a part where the three sectors overlap. This is where most commentators point to when they talk about social

Boston, J., J. Martin, J. Pallot, and P. Walsh. Public Management: The New Zealand Model, Oxford University Press, UK, 1996

2

U K Ci vil S oc i e ty Al ma na c 2 01 2

6|P a g e

SWK1048 Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook

3

enterprise- as an activity that incorporates a public service ethos, voluntary sector activism and the marketplace behaviours of a private company. Social enterprises exist across the range of these overlapping areas, but social enterprise can be seen more clearly in the very middle of this model. Case-study It is tempting to provide some big and famous social enterprise casestudies to illustrate my points at this point. I could mention Jamie Olivers Fifteen Foundation or the mutually owned John Lewis Partnership but they are complicated businesses.

EXERCISE 3

To keep it simple at the moment, watch this film of one of my first year students presenting to class in 2011.

http://youtu.be/WnYP8n-1L0s?hd=1

What do you think is the social problem Abi is trying to address?

Abi is responding to an experience she had and which affected her directly. This is often the case with social entrepreneurs. Her younger brother was struggling with his homework and her mum found herself unable to help him understand the skill that lay behind the homework. Abis example was annotating a film script. Her solution exists right in the middle of the model we have been looking at. The people who benefit from her proposed business are: Parents and children (voluntary sector) by creating better homework outcomes Schools and government (public sector) by helping teachers overcome barriers to homework setting and completion, and

Note that the term incorporate also means to form a Company. Did you spot my pun?! Groan.

7|P a g e

SWK1048 Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook

She will be running a (private sector) company earning its own income and therefore no reliant on government grants or philanthropic giving, although she may make use of these sources of funds to start and grow.

Her solution, Abis way of making the world a little bit better, is not something schools can achieve, on their own. Its not something that parents or pupils can solve on their own, and it would not be right to make lots of private profit out of the poorest parents or least able to help themselves. Breaking it down What this case study allows us to do is to break down our understanding of the idea social enterprise into three parts. Remember that the PURPOSE of social enterprise is to make the world a better place, in other words to create social change for the better. Social Innovation o ideas to change the way society works Social Entrepreneurship o the processes of getting the idea into a business format Social Enterprise o the venture that emerges from the innovation

Social Innovation If our understanding of the term social is to make the world a better place, then innovation can be understood to be introducing something new into the world to achieve that goal, however we describe better. Joseph Schumpeter (1934 ), perhaps the first theorist on entrepreneurship and innovation, describes five features of social innovation 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. The introduction of a new product or an improved version of an existing product The introduction of an improved method of production The development of a new market (or entry into an existing market for a new player) The development of a new source of supply or supply chain The more efficient or effective organization of any industry or sector.

4

So, innovation can happen with respect to a product or a service, or the way in which that product or service is manufactured or provided within a company. It can happen in the marketplace -that set of relations made between companies selling goods and customers buying them. It can extend to the way in which the materials are supplied to the marketplace, or even the way in which that market is configured- the practices and norms that characterise the marketplace. These changes are dynamically described by Schumpeter as creative destruction. This term is important because it highlights that the changes that occur in a system like a marketplace is not planned, or always a good thing. In fact, these cycles of change can be very destructive. 5 Schumpeter suggested (1942 ) that companies, products, market rules and even social relations between people are destroyed and eliminated as capitalism crashes around the world trying to find 6 new places to operate (Harvey, 2010 ), tearing down the old ways (social relations) in which

Schumpeter, J. (1934), The Theory of Economic Development, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. 5 Schumpeter, J. (1942), Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, Cambridge, MA: Harper and Row: New York. 6 Harvey, David (2010). The Enigma of Capital and the Crises of Capitalism. London: Profile Books. p. 85

8|P a g e

SWK1048 Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook

7

communities organise themselves (Berman, 1987 ), even changing the ways in which communities 8 relate to each other across the world in constantly changing flows (Castells 1989 ). So, the theorists tell us that the capitalist system is constantly changing, and it changes the rules of the game constantly. These changes are not always good, but those who write about social innovation suggest that good things can be created out of the rubble of the last set of social relations. The internet is a good example of this sort of shift in social relations brought about by an innovation. Before the internet, people had to relate to each other with the relatively slow means of letters, faxes, and flying around the world to meet each other in person. Now, with skype, facebook and email we can communicate face-to-face across the globe from our homes. This has created new products, like the mobile phone, and then the smart phone and the tablet computer, all straight out of science fiction movies like Star Trek. It has even created products that even geeks didnt imagine, like the $4bn a year market in mobile phone ringtone downloads, that wasnt invented until 1997. Its not necessary to be the first to create an innovation (Rogers 1962 ) and there are number of methods that can be used to develop an innovative approach as an individual and as an 10 organisation . These processes can be called social entrepreneurship.

9

Social Entrepreneurship

We see a lot of entrepreneurs on television these days and we have a number of expectations of what they are and what they can do.

EXERCISE 5:

Think of some famous entrepreneurs that you have heard of and note down a number of characteristics that you think make them entrepreneurs.

If you thought of people like Alan Sugar, Richard Branson, Lakshmi Mittal, Simon Cowell, Anita Roddick, Theo Paphitis, Warren Buffet you are on the right lines. When it comes to characteristics, you probably thought of: Risk taker Aggressive Passionate

7 8

Berman, Marshall (1987). All That is Solid Melts into Air. p. 99 Castells, Manuel (1996, second edition, 2000). The Rise of the Network Society, The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture Vol. I. Cambridge, MA; Oxford, UK: Blackwell 9 Rogers, E. (1962), Diffusion of Innovation, New York, NY: Free Press. 10 http://www.nesta.org.uk/publications/assets/features/the_open_book_of_social_innovation

9|P a g e

SWK1048 Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook

Calm Interested in money

In fact the list can extend to hundreds of characteristics. A quick check on the internet will show you thousands of websites claiming to have found the magic three, five, seven or ten important characteristics of an entrepreneur. This is because these are based on a psychological understanding 11 of what an entrepreneur is. Of the thousands of academic papers studying this, a few traits are commonly raised: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. A desire for significant achievements, mastering of skills, control, or high standards, Self-directed competence to complete tasks and reach goals, innovativeness, ability to tolerate high levels of stress, need for to have control over ones life and work activity, and the ability to anticipate change and adapt with low levels of support or training.

Entrepreneurship isnt something that only heroic individuals do. These characteristics can be learnt about, and fostered in particular environments. These characteristics may pre-dispose someone to be innovative, but dont guarantee such behaviour. So, the entrepreneur identifies a problem, identifies a possible solution and then implements the solution. Further to this, an innovative social entrepreneur doesnt passively spot a social problem, or identify a solution that already exists. Instead, the entrepreneur seems to almost create an 12 opportunity through the following activities : Questioning Observing Experimenting Networking the results

Importantly, they dont do this once. They do it lots of times, in very small steps. In reality, entrepreneurs are not heros and superhumans; they dont take risks. Instead, they take small steps and keep checking and modifying their ideas as they go along.

Effectuation

According to entrepreneurship researcher Saras Sarasvathy, entrepreneurs arent different from anyone else; they simply adopt a different approach to problem solving.

EXERCISE 7:

Watch this film http://bigthink.com/ideas/15302 and make notes in what you think are they key activities that entrepreneurs employ. Make a note of the behaviours that you think you already practice. Make a note of the behaviours that you think you could do with some more experience NOTES

11

Andreas Rauch, Michael Frese (2007) Let's put the person back into entrepreneurship research: A meta-analysis on the relationship between business owners' personality traits, business creation, and success European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology Vol. 16, Iss. 4, 12 http://gsbblogs.uct.ac.za/gsbresearchforum/files/2010/03/2008-SEJ-Entrepreneur-Behaviors-Dyer-Hal-Clay.pdf

10 | P a g e

SWK1048 Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook

Social Enterprise

The venture that arises out of social innovation and processes of social entrepreneurship involves entrepreneurs coming together with ethical consumers in a marketplace to buy and sell in order to solve a social problem. For social entrepreneurship to turn into a social enterprise the following ingredients are needed: People working together to create a 13 product or service (the company) and sharing risk 14 and reducing the costs of transacting with each other Ethical consumers willing to purchase the product or service A marketplace in which commonly accepted rules of trade allow for a flow of materials and information through buying and selling Supplies and suppliers of materials and information to allow the product and service. Making the world a better place can involve ethical activity in each and all of these areas. If we take the company as the key institution in the centre, we can then map the relationships between the company and all the other human and non-human actors in the network . The following list is not exhaustive but provides an overview of the types of socially entrepreneurial activities that can occur across the marketplace.

13

One of the most important legal benefits of creating a company is the safeguarding of personal assets from loss in a business transaction 14 Known as the transaction theory of the firm Coase, Ronald H. (1937). "The Nature of the Firm". Economica 4 (16): 386405

11 | P a g e

SWK1048 Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook

FIGURE 4 A VERY BASIC MODEL OF THE ESSENTIAL INGREDIENTS IN A SOCIALLY JUST MARKET

External mission of the company Customer/beneficiary oriented o Selling a product to make profit to re-use the profit for a good cause o Providing a product or service for free to poor or socially excluded people o Providing a service or creating a social outcome that the government is not providing Marketplace oriented o Changing the rules of the marketplace- market-making Shareholder oriented o Including workers as shareholders who receive profits in dividend o Including customers/beneficiaries as shareholders who receive profits in dividend Stakeholder oriented o Including community groups in decision-making o Protecting or enhancing the environment Internal mission of the company o Employee ownership or decision-making Product/service oriented o Reducing the amount of materials required in a product o Reducing the price of a service Suppliers orientation o Fair trading of materials and information o Including supply chain in decision-making o Investing in supply-chain capacity and equity

15

Some of the changes in the system are not achieved solely by come company or the workers inside that company. Often these changes are achieved by groups of actors working across boundaries, 16 across the system- all collaborating to make systemic and large scale change. These collaborations are called social movements. Tilly suggests that there are three characteristics of a social movement.

17

15

A distinction can be made between a customer who pays for a product or service, and a beneficiary who benefits from the product. Often, the customer is not the same as a beneficiary-like when the government (customer) pays for a disabled person (beneficiary) to receive a service 16 The central concept system embodies the idea of a set of elements connected together which form a whole, this showing properties which are properties of the whole, rather than properties of its component parts. Checkland, P. (1981). Systems Thinking, Systems Practice. John Wiley & Sons

12 | P a g e

SWK1048 Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook

(1) Campaigns: a sustained, organized public effort making collective claims of target authorities; (2) Repertoire (repertoire of contention): employment of combinations from among the following forms of political action: creation of special-purpose associations and coalitions, public meetings, solemn processions, vigils, rallies, demonstrations, petition drives, statements to and in public media, and pamphleteering; and (3) WUNC displays: participants' concerted public representation of worthiness, unity, numbers, and commitments on the part of themselves and/or their constituencies.

Social justice

All of the commentary above is based on three key assumptions: (1) (2) (3) That society should be just, That society is not yet just, and Everyone has the responsibility to make society just.

This idea of social justice is quite important to understand the purpose of social entrepreneurship. Social justice is the idea that all humans should have equal dignity and should work together to achieve that equity. These are the ideas of equality and solidarity. For many centuries, activists and theorists have identified poverty as a major problem for society, yet even when social groups are lifted out of extreme poverty, significant social problems continue to exist, such as poor health, early death, poor education. In recent years, the idea has emerged that the root of many social problems lies in inequality. READ: http://www.scribd.com/doc/25873703/How-unequal-is-Britain People have unequal amounts of Wealth Access to materials Access to services provided by governments Access to decision-making bodies Power to change their lives

Not matter how rich a country gets, it does not mean that you can expect to live longer or have better health in the country. Watch this film http://www.ted.com/talks/richard_wilkinson.html Whilst the Spirit Level theory is subject to much debate, it prompts us to think that if a just society is more equal and more cohesive than now. When we are thinking about social entrepreneurship, we may have a gut feel of what things should be better in the world, but we also need to have a robust theory of social change, otherwise we will end up trying to change the wrong things, or end up changing lots of things that have no impact on the social problem.

A good Theory of Change helps us to handle complexity adequately without falling into over-simplification. Doug Reeler, 2005

17

Charles Tilly (2004) Social Movements, 17682004, Boulder, CO, Paradigm Publishers.

13 | P a g e

SWK1048 Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook

Developing a theory of social change. Part of the skill of being a social entrepreneur is communicating how the world will change because of the new product or service, or marketplace configuration. The social entrepreneur recognises how complex the social world is, and works with that complexity. This complexity is known as messy 18 19 issues or wicked problems . Wicked problems are the sorts of social problem where we cant agree on what the question is, let alone what the solution should be. When we are faced with a messy issue, we have to be very careful about how we identify the problem, what the scope of the problem is, and who gets to decide what is important in a particular problem context. In thinking about the problem we need to: Show the context in which we are facing a social problem (temporal, geographic, social, cultural, economic, political, etc.). Identify the issues that we face. Represent the actors involved (public, private, civil society), their relationships, values, attitudes, abilities and behaviour Incorporate formal and non-formal institutions (public policies, legal framework, standards, customs, cultural patterns, values, beliefs, consensual norms, etc.) that support the desired change. Visualize the present and, after analysing current reality, projecting an image of the future so that the Rich Picture embodies as much a vision of the present as of the future.

Summary This Unit has explored some basic concepts within the field of activity and study called social entrepreneurship. The learning outcome for this Unit was to describe social problems and identify possible market-based interventions to solve those problems. We have established that the purpose of social entrepreneurship is to make the world a slightly better place and we have considered different ways of thinking about that social change. We have introduced the concept of the market-place and the different actors within that marketplace. We have split social enterprise into three concepts- innovation, the processes of entrepreneurship that implement the innovation and the organisations and institutions that result from the processes of entrepreneurship. We have also begin considering what the social problems are that we are concerned to solve. These are just the starting point. The remainder of this handbook is designed to further deepen your understanding of these challenges and to give you the opportunity to explore the practical application of social entrepreneurship activities.

18

Ackoff, Russell, (1974) "Systems, Messes, and Interactive Planning" Portions of Chapters I and 2 of Redesigning the Future. New York/London: Wiley,. 19 Conklin, Jeff; Wicked Problems & Social Complexity, Chapter 1 of Dialogue Mapping: Building Shared Understanding of Wicked Problems, Wiley, November 2005.

14 | P a g e

SWK1048 Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook

Unit 2: Understanding me- my personal assets, skills and resources and my innovation orientation

Introduction

You are your most valuable asset- your knowledge, skills and experiences are all key resources in developing a venture that can help to change the world. In order to thrive as a social entrepreneur or work in a socially innovative environment it is important to understand yourself, your skills, experiences and attitudes that are tools that you use in creating a new venture. You also will achieve much more if you can work interactively with other people towards your objectives, so team and group working is essential. Knowing people, developing your own networks and getting them people to help you is known as social capital. Building these skills up systematically is an essential part of what is known as professional development planning or PDP. The objective of this unit is to understand personal assets and to develop social capital in social entrepreneurship

EXERCISE 8: Entrepreneurial Orientation

Take the test at http://get2test.net/index.htm Note the results, do you think like an entrepreneur?

Social capital

No matter how entrepreneurial you might be, getting things done requires other people. Before money (financial capital) the most important resource that you can access is that of social capital. It is free and it can be invested in and increased quite readily. For John Field (2003: 1-2) the central thesis of social capital theory is that 'relationships matter'. The central idea is that 'social networks are a valuable asset'. Interaction enables people to build communities, to commit themselves to each other, and to knit the social fabric. A sense of belonging

15 | P a g e

SWK1048 Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook

and the concrete experience of social networks (and the relationships of trust and tolerance that can 20 be involved) can, it is argued, bring great benefits to people . Exhibit : Putnam - why social capital is important First, social capital allows citizens to resolve collective problems more easily People often might be better off if they cooperate, with each doing her share. ... Second, social capital greases the wheels that allow communities to advance smoothly. Where people are trusting and trustworthy, and where they are subject to repeated interactions with fellow citizens, everyday business and social transactions are less costly. A third way is which social capital improves our lot is by widening our awareness of the many ways in which our fates are linked... When people lack connection to others, they are unable to test the veracity of their own views, whether in the give or take of casual conversation or in more formal deliberation. Without such an opportunity, people are more likely to be swayed by their worse impulses. The networks that constitute social capital also serve as conduits for the flow of helpful information that facilitates achieving our goals. Social capital also operates through psychological and biological processes to improve individuals lives. Community connectedness is not just about warm fuzzy tales of civic triumph. In measurable and welldocumented ways, social capital makes an enormous difference to our lives. Robert Putnam (2000) Bowling Alone: The collapse and revival of American community, New York: Simon and Schuster: 288-290

Developing Social Capital

17 IDEAS FOR CONSTRUCTING EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING OPPORTUNITIES TO EXPAND YOUR NETWORK 21 INTO YOUR LEARNING PLAN 1. 2. Attend monthly meetings of a local community or business group of interest to your career with the goal of meeting at least two new people at each meeting. Join a college or university club and attend meetings, participate in functions, and exchange business cards with members and others to whom the club members come into contact with on regular occasions. At each meeting talk with at least two people exchanging business cards and then follow up within 10 to 14 days to develop a working relationship that is mutually beneficial where desirable. Visit with a lecturer and borrow one of several books he/she has in his/her personal library regarding networking best practices, tools and techniques for developing an entry-level preprofessional network system and write a reflective journal. Plan to have lunch or breakfast at least once every two weeks with someone within the college / university or the external business community but outside your discipline.

3.

4.

5.

20

Further reading at Smith, M. K. (2000-2009). 'Social capital', the encyclopedia of informal education, www.infed.org/biblio/social_capital.htm . 21 Modified from http://www.google.co.uk/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&frm=1&source=web&cd=4&cad=rja&ved=0CFAQFjAD&url=http%3A%2F %2Fjournals.cluteonline.com%2Findex.php%2FJBCS%2Farticle%2Fdownload%2F4886%2F4979&ei=93G3UNu9FaeU0QXD84D4C Q&usg=AFQjCNGctvr8ma6zIvmv2FRx6G-0VT_LAA

16 | P a g e

SWK1048 Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook

6.

7. 8. 9.

10. 11. 12. 13. 14.

Attend the college or university Career Day and other academic career planning presentations organized by the school for the expressed purpose of meeting practitioners who may have a mutual interest as you. Join a professional organization or a social/community group in the greater community area to develop contacts with their organization. Utilize the class assignments to find a mentor in the greater community area to meet contacts within his/her organization and write a reflective journal. Maintain a file on individuals that you come in contact with at the University with their personal and professional areas of interest stay in touch each semester with handwritten notes, email correspondence and periodic visits being alert for articles or information which might be of interest to the person. Invest in business cards to present to others. Send periodic holiday cards to peers, ex-employers, faculty, and staff as a way to keep contact with these people. Develop good relationships with secretaries and other key informants so that they will be more willing to give your messages to their bosses and write a reflective journal. Actively participate in at least three pre-professional organization meetings on community, entrepreneurial, managerial or leadership topics. Volunteer to be a student ambassador or host to guest speakers and at college outreach activities to expand ones network and contacts and write a reflective journal.

Exercise 9: Building Social Capital

What did you learn from your social capital-building activities?

How might they be useful to your social problem?

17 | P a g e

SWK1048 Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook

UNIT 3 Creativity and innovation

Social innovation refers to new strategies, concepts, ideas and organizations that meet social needs of all kinds from working conditions and education to community development and health and that extend and strengthen civil society. The term has overlapping meanings. It can be used to refer to social processes of innovation, such as open source methods and techniques. Alternatively it refers to innovations which have a social purpose like microcredit or distance learning. The concept can also be related to social entrepreneurship (entrepreneurship is not necessarily innovative, but it can be a means of innovation) and it also overlaps with innovation in public policy and governance. Social innovation can take place within government, the for-profit sector, the nonprofit sector (also known as the third sector), or in the spaces between them. Research has focused on the types of platforms needed to facilitate such cross-sector collaborative social innovation.

Provocative. Just one word . . . provocative. Until recently, prospective students at All Souls College, at Oxford University, took a one-word exam. The Essay, as it was called, was both anticipated and feared by applicants. They each flipped over a piece of paper at the same time to reveal a single word. The word might have been innocence or miracles or water or provocative. Their challenge was to craft an essay in three hours inspired by that single word. There were no right answers to this exam. However, each applicants response provided insights into the students wealth of knowledge and ability to generate creative connections. The New York Times quotes one Oxford professor as saying, The unveiling of the word was once an event of such excitement that even nonapplicants reportedly gathered outside the college each year, waiting for news to waft out. This challenge reinforces the fact that everythingevery single wordprovides an opportunity to leverage what you know to stretch your imagination. For so many of us, this type of creativity hasnt been fostered. We dont look at everything in our environment as an opportunity for ingenuity. In fact, creativity should be an imperative. Creativity allows you to thrive in an ever changing world and unlocks a universe of possibilities. With enhanced creativity, instead of problems you see potential, instead of obstacles you see opportunities, and instead of challenges you see a chance to create breakthrough solutions. Look around and it becomes clear that the innovators among us are the ones succeeding in every arena, from science and technology to education and the arts. Nevertheless, creative problem solving is rarely taught in school, or even considered a skill you can learn. Sadly, there is also a common and often-repeated saying, Ideas are cheap. This statement discounts the value of creativity and is utterly wrong. Ideas arent cheap at alltheyre free. And theyre amazingly valuable. Ideas lead to innovations that fuel the economies of the world, and they prevent our lives from becoming repetitive and stagnant. They are the cranes that pull us out of well-worn ruts and put us on a path toward progress. Without creativity we are not just condemned to a life of repetition, but to a life that slips backward. In fact, the biggest failures of our lives are not those of execution, but failures of imagination. As the renowned American inventor Alan Kay famously said, The best way to predict the future is to invent it. We are all inventors of our own future. And creativity is at the heart of invention. As demonstrated so beautifully by the one-word exam, every utterance, every object, every decision, and every action is an opportunity for creativity. This challenge, one of many tests given over several days at All Souls College, has been called the hardest exam in the world. It required both a breadth of knowledge and a healthy dose of imagination. Matthew Edward Harris, who took the exam in 2007, was assigned the word harmony. He wrote in the Daily Telegraph that he felt like a chef rummaging through the recesses of his refrigerator for unlikely soup ingredients. This homey simile is a wonderful reminder that these are skills that we have an opportunity to call upon every day as we face challenges as simple as making soup and as monumental as solving the massive problems that face the world. I teach a course on creativity and innovation at the Hasso Plattner Institute of Design, affectionately called the d.school, at Stanford University. This complements my full-time job as Executive Director of the Stanford Technology Ventures Program (STVP), in the Stanford School of Engineering. At STVP our

18 | P a g e

SWK1048 Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook

mission is to provide students in all fields with the knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed to seize opportunities and creatively solve major world problems. On the first day of class, we start with a very simple challenge: redesigning a name tag. I tell the students that I dont like name tags at all. The text is too small to read. They dont include the information I want to know. And theyre often hanging around the wearers belt buckle, which is really awkward. The students laugh when they realize that they too have been frustrated by the same problems. Within fifteen minutes the class has replaced the name tags hanging around their necks with beautifully decorated pieces of paper with their names in large text. And the new name tags are pinned neatly to their shirts. Theyre pleased they have successfully solved the problem and are ready to go on to the next one. But I have something else in mind. . . . I collect all of the new name tags and put them in the shredder. The students look at me as though Ive gone nuts! I then ask, Why do we use name tags at all? At first, the students think that this is a preposterous question. Isnt the answer obvious? Of course, we use name tags so that others can see our name. They quickly realize, however, that theyve never thought about this question. After a short discussion, the students acknowledge that name tags serve a sophisticated set of functions, including stimulating conversations between people who dont know each other, helping to avoid the embarrassment of forgetting someones name, and allowing you to quickly learn about the person with whom you are talking. With this expanded appreciation for the role of a name tag, students interview one another to learn how they want to engage with new people and how they want others to engage with them. These interviews provide fresh insights that lead them to create inventive new solutions that push beyond the limitations of a traditional name tag. One team broke free from the size constraints of a tiny name tag and designed custom T-shirts with a mix of information about the wearer in both words and pictures. Featured were the places they had lived, the sports they played, their favorite music, and members of their families. They vastly expanded the concept of a name tag. Instead of wearing a tiny tag on their shirts, each shirt literally became a name tag, offering lots of topics to explore. Another team realized that when you meet someone new, it would be helpful to have relevant information about that person fed to you on an as-needed basis to help keep the conversation going and to avoid embarrassing silences. They mocked up an earpiece that whispers information about the person with whom you are talking. It discreetly reveals helpful facts, such as how to pronounce the persons name, his or her place of employment, and the names of mutual friends. Yet another team realized that in order to facilitate meaningful connections between people, it is often more important to know how the other person is feeling than it is to know a collection of facts about them. They designed a set of colored bracelets, each of which denotes a different mood. For example, a green ribbon means that you feel cheerful, a blue ribbon that you are melancholy, a red ribbon that youre stressed, and a purple ribbon that you feel fortunate. By combining the different colored ribbons, a wide range of emotions can be quickly communicated to others, facilitating a more meaningful first connection. This assignment is designed to demonstrate an important point: there are opportunities for creative problem solving everywhere. Anything in the world can inspire ingenious ideaseven a simple name tag. Take a look around your office, your classroom, your bedroom, or your backyard. Everything you see is ripe for innovation. Adapted from INGENIUS by Tina Seelig, Ph.D. Copyright 2012 by Tina L. Seelig.

19 | P a g e

SWK1048 Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook

EXERCISE 10

What does creativity look like? Draw a picture of creativity

20 | P a g e

SWK1048 Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook

Creativity is just connecting things. When you ask creative people how they did something, they feel a little guilty because they didnt really do it, they just saw something. It seemed obvious to them after a while. Thats because they were able to connect experiences theyve had and synthesize new things. Steve Jobs, Wired magazine, 1996

Watch this film http://www.ted.com/talks/tim_brown_on_creativity_and_play.html

EXERCISE 11

Draw your neighbour really quickly

21 | P a g e

SWK1048 Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook

The Rules of Brainstorming

We happen to think idea generation is an art form. It's about setting a safe, creative space for people to feel like they can say anything, be wild, not be judged, so that new ideas can be born. Traditionally, the group brainstorm is an activity to generate ideas in-person. With OpenIDEO, the community is turning that model on its head by creating a digital space where ideas spark and fly. We're excited to see the Concepting Phase turning into this new form of digital brainstorming. To help you generate better ideas, here's a set of rules we use in traditional group brainstorming, to set the boundaries of that creative space. The rules for digital brainstorming have yet to be discovered. Based on your experience maybe you can contribute some in the comments!

1. Defer judgment Creative spaces don't judge. They let the ideas flow, so that people can build on eachother and foster great ideas. You never know where a good idea is going to come from, the key is make everyone feel like they can say the idea on their mind and allow others to build on it. On OpenIDEO, we've made this literally into a Build On This button. Click on it to start your own idea, building on someone elses. This still means we pose questions and provocations so that the ideas can get to a better place. Take a look at the comments section under each of the Concepts, where we see lots of builds and questions tackling different dimensions of the idea. 2. Encourage wild ideas Wild ideas can often give rise to creative leaps. In thinking about ideas that are wacky or out there we tend to think about what we really want without the constraints of technology or materials. We can then take those magical possibilities and perhaps invent new technologies to deliver them. We say embrace the most out-of-the-box notions and build build build... 3. Build on the ideas of others Being positive and building on the ideas of others take some skill. In conversation, we try to use and instead of but... On OpenIDEO, you can click the button that says Build on this and then say And... Or leave someone a comment with a new build. 22 | P a g e

SWK1048 Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook

4. Stay focused on the topic We try to keep the discussion on target, otherwise you can diverge beyond the scope of what we're trying to design for. 5. One conversation at a time Of course on OpenIDEO, there's lots of conversations happening at once, which is great! Always think about the challenge topic and how this could apply. 6. Be visual In live brainstorms we use coloured markers to write on Post-its that are put on a wall. Nothing gets an idea across faster than drawing it. Doesnt matter how terrible of a sketcher you are! It's all about the idea behind your sketch. On OpenIDEO, we love seeing photos, sketches, found images for your ideas. You could also try your hand at sketching it out or mocking it up on the computer. We love visual ideas as the images make them memorable. Does someone elses idea excite you? Maybe make them an image to go with their idea. 7. Go for quantity Aim for as many new ideas as possible. In a good session, up to 100 ideas are generated in 60 minutes. Crank the ideas out quickly. Our Concepting challenges usually run for 2-4 weeks. How do we keep up the pace and the momentum and get more quantity? It's up to you guys to spark and build!

23 | P a g e

SWK1048 Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook

EXERCISE 12: 30 Circles creativity exercise

In one minute, adapt as many circles as you can into objects, by drawing on them

Inspiration

Balloon Kenya blog Posted on June 8, 2011 Inspiration is an amazingly powerful feeling. It quickly fills you with drive and determination as your mind ventures off on a series of tangents. I experienced such a feeling a couple of months back when I was interning at the Young Foundation. I was sitting in an ideation class with Stu who works there and we were discussing my idea for Kenya when he mentioned gap years and business training. Suddenly I had this feeling of joy and energy as an idea quickly started to formulate in my mind. I left the office soon after too excited to stay and I headed for the underground to journey home. On my commute I got out a notepad and quickly jotted down some more thoughts. And by the time I got off the train to walk the final few steps to my house I was bouncing along with a huge grin on my face. It seemed like in the space of an hour I had gone from being farely clueless on my future to having a very clear idea of what I wanted to do. I was suddenly inspired to found my own social enterprise. I was tired of waiting for opportunities to arise and I was excited that now I was going to make something happen. I returned home and quickly grabbed my mum to explain my idea. After all mums are the crucial litmus test and she would have to like it. Thankfully she uttered the words, its brilliant and I knew I was on to something. And so a fairly average day had in an instance turned to possibly one of the defining days of my life. Inspiration had hit me and I couldnt be happier. KenyaWorks was born

24 | P a g e

SWK1048 Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook

Unit 4 Social Problems and Opportunities

Anti-social behaviour, homelessness, drugs, mental illness: all problems in todays society. But what makes a problem social? This unit will help you to discover how these issues are identified, defined, 22 given meaning and acted upon. You will also look at the conflicts within social science in this area . Social problems, also called social issues, affect every society, great and small. Even in relatively isolated, sparsely populated areas, a group will encounter social problems. Part of this is due to the fact that any members of a society living close enough together will have conflicts. Its virtually impossible to avoid them, and even people who live together in the same house dont always get along seamlessly. On the whole though, when social problems are mentioned they tend to refer to the problems that affect people living together in a society. The list of social problems is huge and not identical from area to area. Some predominant social issues include the growing divide between rich and poor, domestic violence, unemployment, pollution, urban decay, racism and sexism, and many others. Sometimes social issues arise when people hold very different opinions about how to handle certain situations like unplanned pregnancy. While some people might view abortion as the solution to this problem, other members of the society remain strongly opposed to its use. In itself, strong disagreements on how to solve problems create divides in social groups. Other issues that may be considered social problems aren't that common in the US and other industrialized countries, but they are huge problems in developing ones. The issues of massive poverty, food shortages, lack of basic hygiene, spread of incurable diseases, ethnic cleansing, and lack of education inhibits the development of society. Moreover, these problems are related to each other and it can seem hard to address one without addressing all of them. It would be easy to assume that a social problem only affects the people whom it directly touches, but this is not the case. Easy spread of disease for instance may tamper with the society at large, and its easy to see how this has operated in certain areas of Africa. The spread of AIDs for instance has created more social problems because it is costly, it is a danger to all members of society, and it leaves many children without parents. HIV/AIDs isnt a single problem but a complex cause of numerous ones. Similarly, unemployment in America doesnt just affect those unemployed but affects the whole economy. Its also important to understand that social problems within a society affect its interaction with other societies, which may lead to global problems or issues. How another nation deals with the problems of a developing nation may affect its relationship with that nation and the rest of the world for years to come. Though the United States was a strong supporter of the need to develop a Jewish State in Israel, its support has come at a cost of its relationship with many Arabic nations. Additionally, countries that allow multiple political parties and free expression of speech have yet another issue when it comes to tackling some of the problems that plague its society. This is diversity of solutions, which may mean that the country cannot commit to a single way to solve an issue, because there are too many ideas operating on how to solve it. Any proposed solution to something that affects society is likely to make some people unhappy, and this discontent can promote discord. On the other hand, in countries where the government operates independently of the people and

22

Edited from http://openlearn.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=399004&direct=1 25 | P a g e

SWK1048 Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook

where free speech or exchange of ideas is discouraged, there may not be enough ideas to solve issues, and governments may persist in trying to solve them in wrongheaded or ineffective ways. The very nature of social problems suggests that society itself is a problem. No country has perfected a society where all are happy and where no problems exist. Perhaps the individual nature of humans prevents this, and as many people state, perfection many not be an achievable goal.

Problems as opportunities

It is easy to assume that Africa is a continent of despair, disaster and disarray. But those who live and work there say that there is another story to be told one of resilience, entrepreneurialism and resourcefulness. Experience shows that out of difficult circumstances can emerge the best kind of innovation simple yet life-changing for those who embrace it. One of the most notable recent examples has been Vodafone's launch of the M-Pesa payment system. M-Pesa started out in Kenya, and is a method of transferring cash that bypasses the need for banks and specialist money transfer services. Users register and then receive a Sim card, which features an application that acts as a virtual wallet. They can put money into their M-Pesa account via agents. This can be transferred via mobile phone to another person, who can then withdraw the cash at another agent. None of this might seem innovative to a reader who is used to electronic banking and instant access to their funds, but M-Pesa was initially designed to help Kenyans overcome the problem of the huge distances some people had to travel to money transfer agencies. Initially it was aimed at workers who had moved to city areas wanting to send money back to family and dependants in rural areas. But the scheme has taken off in ways that Vodafone had not anticipated. Customers have been using the service to pay bills, and employers 23 sometimes pay their staff wages via the system. One of the most insidious, unproductive ways we use time is complaining about our problems especially when we should be thinking about them as new opportunities. A problem is just a problem because we think of it that way. Stuff happens. If we dont like the stuff, we label it a problem and try to jam the world back into the way it was going before. If we do like the stuff, we label it an opportunity and try to take advantage of it. The difference between a problem and an opportunity is what we do with it, not what it is to begin with.

23

http://www.guardian.co.uk/inspire-innovate/problems-opportunities 26 | P a g e

SWK1048 Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook

EXERCISE 13

Have a think about the following ventures and identify the problems that they solve for their customers. Apple ipod

Nike trainers

Amazon books

Dyson vacuum cleaner

What is it about their solutions that make people want to PAY MONEY for them?

27 | P a g e

SWK1048 Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook

African innovations24

HIPPO WATER ROLLER Idea: The Hippo water roller is a drum that can be rolled on the ground, making it easier for those without access to taps to haul larger amounts of water faster. Problem: Two out of every five people in Africa have no nearby water facilities and are forced to walk long distances to reach water sources. Traditional methods of balancing heavy loads of water on the head limit the amount people can carry, and cause long-term spinal injuries. Women and children usually carry out these time-consuming tasks, missing out on educational and economic opportunities. In extreme cases, they can be at increased risks of assault or rape when travelling long distances.

Method: The Hippo roller can be filled with water which is then pushed or pulled using a handle. The weight of the water is spread evenly so a full drum carries almost five times more than traditional containers, but weighs in at half the usual 20kg, allowing it to be transported faster. A steel handle has been designed to allow two pushers for steeper hills. Essentially it alleviates the suffering people endure just to collect water and take it home. Boreholes or wells can dry out but people can still use the same roller [in other wells]. One roller will typically serve a household of seven for five to seven years, said project manager Grant Gibbs. Outcome: Around 42,000 Hippo rollers have been sold in 21 African countries and demand exceeds supply. Costing $125 each, they are distributed through NGOs. A mobile manufacturing unit is set to begin making them in Tanzania. Nelson Mandela has made a personal appeal for supporting for the project, saying it will positively change the lives of millions of our fellow South Africans. ETHANOL COOKING OIL PLANT Idea: Refining locally sourced cassava into ethanol fuel to provide cleaner cooking fuel. Problem: Forests in Africa are being cut down at a rate of 4m hectares a year, more than twice the worldwide average rate. Some of this is fuelled by demand for wood and charcoal, which the UN estimates is still used in almost 80% of African homes as a cheaper option to gas. The smoke from cooking using these solid fuels also triggers respiratory problems that cause nearly 2 million deaths in the developing world each year. Method: CleanStar Mozambique, a partnership between CleanStar and Danish industrial enzymes producer Novozymes, has opened the worlds first sustainable cooking-fuel plant in Mozambique.

24

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/aug/26/africa-innovations-transform-continent 28 | P a g e

SWK1048 Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook

CleanStar has steered clear of monoculture crops in favour of sustainable farming methods. One-sixth of the final yield comes from locally harvested cassava, which requires farmers to plant in rotation with other edible crops to keep the soil fertile. A Sofala Province-based plant transforms the products into ethanol, which is sold on the local market along with adapted cooking stoves also produced by the company. Outcome: City women are tired of watching charcoal prices rise, carrying dirty fuel, and waiting for the day that they can afford a safe gas stove and a reliable supply of imported cylinders, CleanStar marketing director Thelma Venichand said. They are ready to buy a modern cooking device that uses clean, locally made fuel, performs well and saves them time and money. The plant aims to produce 2m litres of fuel annually, and reach 120,000 households within three years. THE CARDIOPAD Idea: A computer tablet diagnoses heart disease in rural households with limited access to medical services. Problem: Cardiovascular diseases kill some 17 million worldwide annually. In many African countries, those at risk often have to spend huge amounts of money and travel hundreds of miles to reach heart specialists concentrated in main urban centres. The Cameroon Heart Foundation has noted a "sharp spike" in heart disease among its 20 million-strong population, which is served by fewer than 40 heart specialists. Method: A program on the Cardiopad, designed by 24-year-old Cameroonian engineer Arthur Zang, collects signals generated by the rhythmic contraction and expansion of a patient's heart. Electrodes are fixed near the patient's heart. Africa's first fully touch-screen medical tablet then produces a moving graphical depiction of the cardiac cycle, which is wirelessly transmitted over GSM networks to a cardiologist for interpretation and diagnosis. "I designed the Cardiopad to resolve a pressing problem. If a cardiac exam is prescribed for a patient in Garoua in the north of the country, they are obliged to travel a distance of over 900km to Yaound or Douala," Zang says. Outcome: At the Laquintinie, one of the country's biggest hospitals, cardiologist Dr Daniel Lemogoum said that, in a recent survey, three in every five persons who uses the Cardiopad has been diagnosed as hypertensive, or at risk of heart diseases. "These are people who would not necessarily have been aware they are hypertensive. It means sudden deaths might be preventable."

Triggers and inspirations that prompt innovation25

Here we describe some of the triggers and inspirations that prompt innovation, that demand action on an issue, or that mobilise belief that action is possible. 1) Crisis. Necessity is often the mother of invention, but crises can also crush creativity. One of the definitions of leadership is the ability to use the smallest crisis to achieve the greatest positive change. Many nations have used economic and social crises to accelerate reform and innovation and in some cases have used the crisis to deliberately accelerate social innovation. New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina is one example (LousianaRebuilds.info or the New Orleans Institute for Resilience and Innovation); Chinas much more effective response to the Szechuan earthquake is another. Both, in very different ways, institutionalised innovation as part of the response.

25

From the NESTA Open Book of Social Innovation www.nesta.org.uk/library/.../Social_Innovator_020310.pdf 29 | P a g e

SWK1048 Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook

2) Efficiency savings. The need to cut public expenditure often requires services to be designed and delivered in new ways. Major cuts can rarely be achieved through traditional efficiency measures. Instead they require systems change for example, to reduce numbers going into prison, or to reduce unnecessary pressures on hospitals. The right kinds of systems thinking can open up new possibilities. 3) Poor performance highlights the need for change within services. This can act as a spur for finding new ways of designing and delivering public services. The priority will usually be to adopt innovations from elsewhere. 4) New technologies can be adapted to meet social needs better or deliver services more effectively. Examples include computers in classrooms, the use of assistive devices for the elderly, or implants to cut teenage pregnancy. Through experiment it is then discovered how these work best (such as the discovery that giving computers to two children to share is more effective for education than giving them one each). Any new technology becomes a prompt. Artificial intelligence, for example, has been used in family law in Australia and to help with divorce negotiations in the US. 5) New evidence brings to light new needs and new solutions for dealing with these needs, such as lessons from neuroscience being applied to childcare and early years interventions or knowledge about the effects of climate change.

Thinking differently

New solutions come from many sources e.g. adapting an idea from one field to another, or connecting apparently diverse elements in a novel way. Its very rare for an idea to arrive alone. More often, ideas grow out of other ones, or out of creative reflection on experience. They are often prompted by thinking about things in new or different ways. Here, we outline some of the processes that can help to think and see differently. Starting with the user through user research and participant observation, including ethnographic approaches such as user/citizen diaries, or living with communities and individuals to understand their lived worlds. SILK at Kent County Council, for example, used ethnographic research to review the lifestyles of citizens in their area. Positive deviance is an asset-based approach to community development. It involves finding people within a particular community whose uncommon behaviours and strategies enable them to find better solutions to problems than their peers, while having access to the same resources. The Positive Deviance Initiative has already had remarkable results in health and nutrition in Egypt, Argentina, Mali and Vietnam. Reviewing extremes such as health services or energy production in remote communities. Design for extreme conditions can provide insights and ideas for providing services to mainstream users. For example, redesigning buildings and objects to be more easily used by people with disabilities has often generated advances that are useful to everyone. Visiting remains one of the most powerful tools for prompting ideas, as well as giving confidence for action. It is common in the field of agriculture to use model farms and tours to transfer knowledge and ideas. One excellent example is Reggio Emilia, a prosperous town in Northern Italy which, since the Second World War, has developed a creative, holistic and child-centred approach to early years education which acts as an inspiration to early years educators all over the world. Reggio Children is a mixed private-public company which co-ordinates tours and visits to early years centres in the area. 30 | P a g e

SWK1048 Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook

Rethinking space. Many of societys materials, spaces and buildings are unused, discarded and unwanted. Old buildings and factories remain fallow for years, acting as a drain on local communities both financially and emotionally. The trick is to see these spaces and buildings in a more positive light, as resources, assets and opportunities for social innovation. Assets can be reclaimed and reused and, in the process, environments can be revitalised, social needs can be met, and communities energised. One example is the work of activist architect, Teddy Cruz. Cruz uses waste materials from San Diego to build homes, health clinics and other buildings in Tijuana. He has become well-recognised for his low-income housing designs, and for his ability to turn overlooked and unused spaces within a dense, urban neighbourhood into a liveable, workable environment. Another example is the regeneration of Westergasfabriek by ReUse in Amsterdam, or the transformation of a disused elevated railway in New York into an urban park the High Line.

Selecting problems

If I had 60 minutes to solve a problem and my life depended on it, Id spend 55 minutes determining the right question to ask, and 5 minutes thinking aloud about the solution. Albert Einstein At this stage, selecting an unsuitable problem can really set you back. An unsuitable problem is either too narrow, so that it is already framed as a solution, or too broad, so that it is unrealistic to solve within your means. There is no internet connection in my flat TOO NARROW There are no jobs for youths in Northampton TOO BROAD If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses Henry Ford, inventor of the first mass produced car. Your job is to keep asking WHY? Why does this person need a faster horse? Get to the root of the problemwhat needs are left unfulfilled.

Understanding how root causes work26

Root causes work like the way sap flows in a tree. Deep down in the roots, water and nutrients are turned into sap. This flows up the roots, up the trunk, along the branches, and to the many leaves on the tree. Each leaf is a symptom.

26

http://www.thwink.org/sustain/analysis/HowToStrikeAtRoot.htm 31 | P a g e

SWK1048 Enterprising Communities Social Innovation Workbook