Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Perkawinan Sebagai Sarana Penyatuan Kelompok

Hochgeladen von

Irfan Rakhman HidayatOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Perkawinan Sebagai Sarana Penyatuan Kelompok

Hochgeladen von

Irfan Rakhman HidayatCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

MARRIAGE AS GROUP ALLIANCE

Outside industrial societies, marriage is often more a relationship between groups than one between individuals. We think of marriage as an individual matter. Although the bride and groom usually seek their parents approval, the fi nal choice (to live together, to marry, to divorce) lies with the couple. The idea of romantic love symbolizes this individual relationship.

Contemporary Western societies stress the notion that romantic love is necessary for a good marriage. Increasingly this idea characterizes other cultures as well. Described in this chapters Appreciating Anthropology is a cross-cultural study that found romantic ardor to be widespread.

The mass media and migration increasingly spread Western ideas about the importance of love for marriage to other societies. However, marriages in the nonWestern societies where anthropology grew up, even when cemented by passion, remain the concern of social groups rather than mere individuals.

The scope of marriage extends from the social to the political. Strategic marriages are tried and true ways of establishing alliances between groups. People dont just take a spouse; they assume obligations to a group of in-laws. When residence is patrilocal, for example, a woman often must

leave the community where she was born. She faces the prospect of spending the rest of her life in her husbands village, with his relatives. She may even have to transfer her major allegiance from her own group to her husbands.

Bridewealth and Dowry

In societies with descent groups, people enter marriage not alone but with the help of the descent group. Descent-group members often have to contribute to the bridewealth, a customary gift before, at, or after the marriage from the husband and his kin to the wife and her kin. Another word for bridewealth is brideprice, but this term is inaccurate because people with the custom dont usually regard the exchange as a sale. They dont think of marriage as a commercial relationship between a man and an object that can be bought and sold.

Bridewealth compensates the brides group for the loss of her companionship and labor. More important, it makes the children born to the woman full members of her husbands descent group. For this reason, the institution is also called progeny price. Rather than the woman herself, it is her children, or progeny, who are permanently transferred to the husbands group. Whatever we call it, such a transfer of wealth at marriage is common in patrilineal groups.

In matrilineal societies, children are members of the mothers group, and there is no reason to pay a progeny price.

Dowry is a marital exchange in which the brides family or kin group provides substantial gifts when their daughter marries.

For rural Greece, Ernestine Friedl (1962) has described a form of dowry in which the bride gets a wealth transfer from her mother, to serve as a kind of trust fund during her marriage. Usually, however, the dowry goes to the husbands family, and the custom is correlated with low female status. In this form of dowry, best known from India, women are perceived as burdens. When a man and his family take a wife, they expect to be compensated for the added responsibility.

Although India passed a law in 1961 against compulsory dowry, the practice continues. When the dowry is considered insuffi cient, the bride may be harassed and abused. Domestic violence can escalate to the point where the husband or his family burn the bride, often by pouring kerosene on her and lighting it, usually killing her. It should be pointed out that dowry doesnt necessarily lead to domestic abuse. In fact, Indian dowry murders seem to be a fairly recent phenomenon. It also has been estimated that the rate of spousal murders in the contemporary United States may rival the incidence of Indias dowry murders (Narayan 1997).

Sati was the very rare practice through which widows were burned alive, voluntarily or forcibly, on the husbands funeral pyre (Hawley 1994). Although it has become well known, sati was

mainly practiced in a particular area of northern India by a few small castes. It was banned in 1829. Dowry murders and sati are fl agrant examples of patriarchy, a political system ruled by men in which women have inferior social and political status, including basic human rights.

Bridewealth exists in many more cultures than dowry does, but the nature and quantity of transferred items differ. In many African societies, cattle constitute bridewealth, but the number of cattle given varies from society to society. As the value of bridewealth increases, marriages become more stable. Bridewealth is insurance against divorce. Imagine a patrilineal society in which a marriage requires the transfer of about 25 cattle from the grooms descent group to the brides. Michael, a member of descent group A, marries Sarah from group B. His relatives help him assemble the bridewealth. He gets the most help from his close agnates (patrilineal relatives): his older brother, father, fathers brother, and closest patrilineal cousins.

The distribution of the cattle once they reach Sarahs group mirrors the manner in which they were assembled. Sarahs father, or her oldest brother if the father is dead, receives her bridewealth. He keeps most of the cattle to use as bridewealth for his sons marriages. However, a share also goes to everyone who will be expected to help when Sarahs brothers marry. When Sarahs brother David gets married, many of the cattle go to a third group: C, which is

Davids wifes group. Thereafter, they may serve as bridewealth to still other groups. Men constantly use their sisters bridewealth cattle to acquire their own wives. In a decade, the cattle given when Michael married Sarah will have been exchanged widely.

In such societies, marriage entails an agreement between descent groups. If Sarah and Michael try to make their marriage succeed but fail to do so, both groups may conclude that the marriage cant last. Here it becomes especially obvious that such marriages are relationships between groups as well as between individuals. If Sarah has a younger sister or niece (her older brothers daughter, for example), the concerned parties may agree to Sarahs replacement by a kinswoman. However, incompatibility isnt the main problem that threatens marriage in societies with bridewealth. Infertility is a more important concern. If Sarah has no children, she and her group have not fulfi lled their part of the marriage agreement. If the relationship is to endure, Sarahs group must furnish another woman, perhaps her younger sister, who can have children. If this happens, Sarah may choose to stay with her husband. Perhaps she will someday have a child. If she does stay on, her husband will have established a plural marriage.

Most nonindustrial food-producing societies, unlike most foraging societies and industrial nations,

allow plural marriages, or polygamy. There are two varieties; one is common, and the other is very rare. The more common variant is polygyny, in which a man has more than one wife. The rare variant is polyandry, in which a woman has more than one husband. If the infertile wife remains married to her husband after he has taken a substitute wife provided by her descent group, this is polygyny. Reasons for polygyny other than infertility will be discussed shortly.

Durable Alliances

It is possible to exemplify the group-alliance nature of marriage by examining still another common practice: continuation of marital alliances when one spouse dies.

Sororate What happens if Sarah dies young? Michaels group will ask Sarahs group for a substitute, often her sister. This custom is known as the sororate (Figure 11.5). If Sarah has no sister or if all her sisters are already married, another woman from her group may be available. Michael marries her, there is no need to return the bridewealth, and the alliance continues. The sororate exists in both matrilineal and patrilineal societies. In a matrilineal society with matrilocal postmarital residence, a widower may remain with his wifes group by marrying her sister or another female member of her matrilineage sororate Widower marries sister of his deceased wife.

Levirate What happens if the husband dies? In many societies, the widow may marry his brother. This custom is known as the levirate. Like the sororate, it is a continuation marriage that maintains the alliance between descent groups, in this case by replacing the husband with another member of his group. The implications of the levirate vary with age. One study found that in African societies, the levirate, though widely permitted, rarely involves cohabitation of the widow and her new husband. Furthermore, widows dont automatically marry the husbands brother just because they are allowed to. Often, they prefer to make other arrangements (Potash 1986).

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- 2disaster Risk Reduction - Risk AssessmentDokument3 Seiten2disaster Risk Reduction - Risk AssessmentIrfan Rakhman HidayatNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Revisi 1 Red Light and Green LightDokument25 SeitenRevisi 1 Red Light and Green LightIrfan Rakhman HidayatNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- BUDGET Budget Theory in The Public SectorDokument314 SeitenBUDGET Budget Theory in The Public SectorHenry So E DiarkoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (894)

- Reading 2 - Approaches To Resource Allocation in Public SectorDokument52 SeitenReading 2 - Approaches To Resource Allocation in Public SectorEmilyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes SaavedraDokument703 SeitenDon Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes SaavedraBooks86% (7)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Public Sector Economics: The State of Affairs, Problems, and Possible Solutions ADokument32 SeitenPublic Sector Economics: The State of Affairs, Problems, and Possible Solutions AIrfan Rakhman HidayatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Budget Process PresentationDokument37 SeitenBudget Process PresentationKim TonyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Creativity, Innovation, EntrepreneurshipDokument14 SeitenCreativity, Innovation, EntrepreneurshipIrfan Rakhman HidayatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Handbook of PSEDokument794 SeitenHandbook of PSEMawar Putih100% (2)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- Kasus UTS Manajemen Kualitas Sem I THN 2013 PDFDokument3 SeitenKasus UTS Manajemen Kualitas Sem I THN 2013 PDFIrfan Rakhman HidayatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Handbook of PSEDokument794 SeitenHandbook of PSEMawar Putih100% (2)

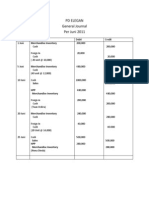

- PD ELEGAN (Tugas Akuntansi) by Irfan Rakhman HidayatDokument3 SeitenPD ELEGAN (Tugas Akuntansi) by Irfan Rakhman HidayatIrfan Rakhman HidayatNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Tugas MPK Bahasa Inggris StrukturDokument1 SeiteTugas MPK Bahasa Inggris StrukturIrfan Rakhman HidayatNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Adverbial ClausesDokument20 SeitenAdverbial ClausesIrfan Rakhman Hidayat100% (1)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- 15business Mathematics CurriculumDokument16 Seiten15business Mathematics CurriculumIrfan Rakhman HidayatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- 8 Principles of Visionary LeadershipDokument2 Seiten8 Principles of Visionary Leadershipnestor_mondragonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Team and Organizationwide Incentive PlansDokument4 SeitenTeam and Organizationwide Incentive PlansIrfan Rakhman Hidayat100% (2)

- Samsung Et ALLDokument15 SeitenSamsung Et ALLIrfan Rakhman HidayatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Resource Management Case Chapter 12 (Irfan Rakhman Hidayat) 1101001014Dokument7 SeitenHuman Resource Management Case Chapter 12 (Irfan Rakhman Hidayat) 1101001014Irfan Rakhman Hidayat100% (5)

- By: Group 3: Dian Vitasari Ayu Lestari Ari Pandowo Anasta Ensenanda WDokument34 SeitenBy: Group 3: Dian Vitasari Ayu Lestari Ari Pandowo Anasta Ensenanda WIrfan Rakhman HidayatNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Petition For Annulment of MarriageDokument6 SeitenPetition For Annulment of MarriagelenaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- Divorce Law of India Needs Urgent AmendmentDokument22 SeitenDivorce Law of India Needs Urgent Amendmentdivorcelawamendment100% (1)

- Ultimate Bridal Shower PartyDokument5 SeitenUltimate Bridal Shower PartyKlEər OblimarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conflicts - Prasnick CaseDokument1 SeiteConflicts - Prasnick Caseai ningNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Rankers' Study Material: Legal ReasoningDokument4 SeitenRankers' Study Material: Legal ReasoningSaurabhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Minoru Fujiki v. Marinay DigestDokument2 SeitenMinoru Fujiki v. Marinay DigestConcon Fabricante100% (1)

- SC Judgements FamilyMatters1 PDFDokument536 SeitenSC Judgements FamilyMatters1 PDFTrisha 11Noch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 11 Attraction and IntimacyDokument116 SeitenChapter 11 Attraction and IntimacyGrace Lindo0% (1)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Paternity Cases - UribeDokument110 SeitenPaternity Cases - UribePeanutbuttercupsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2019 AUSL Pre Week Notes Civil Law PDFDokument59 Seiten2019 AUSL Pre Week Notes Civil Law PDFJDR JDRNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ian HolmDokument8 SeitenIan HolmXepajida Cobin2hoodNoch keine Bewertungen

- Antonia Armas y Calisterio vs. Marietta CalisterioDokument1 SeiteAntonia Armas y Calisterio vs. Marietta CalisterioAllen SoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wills Case DigestDokument3 SeitenWills Case DigestSherine Lagmay Rivad100% (1)

- Fawad Ahsan Versus Chairman, Arbitration Council, IslamabadDokument5 SeitenFawad Ahsan Versus Chairman, Arbitration Council, IslamabadQasim Sher HaiderNoch keine Bewertungen

- University's Taxation Laws Project on Dower RightsDokument8 SeitenUniversity's Taxation Laws Project on Dower RightsNitish Kumar NaveenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Islamic Family LawDokument5 SeitenIslamic Family Lawcatalinc1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Petition For Annulment of MarriageDokument3 SeitenPetition For Annulment of MarriageMarvin Rhick Bulan100% (5)

- Indian Divorce Act 1869Dokument46 SeitenIndian Divorce Act 1869Vaheje BejeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 90 - Siayngco vs. SiayngcoDokument2 Seiten90 - Siayngco vs. SiayngcoSTEPHEN NIKOLAI CRISANGNoch keine Bewertungen

- UCSPDokument44 SeitenUCSPGarreth RoceroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- UV Persons and Family Relations Course SyllabusDokument46 SeitenUV Persons and Family Relations Course SyllabusVal VejanteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Let Not Man Put AsunderDokument159 SeitenLet Not Man Put AsunderVan ParunakNoch keine Bewertungen

- PERSONS AND FAMILY RELATIONS Prof. Elizabeth Aguiling-PangalanganDokument18 SeitenPERSONS AND FAMILY RELATIONS Prof. Elizabeth Aguiling-PangalanganMary LM100% (1)

- Ohio Parenting TimeDokument118 SeitenOhio Parenting TimeAshley GreenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Albano and Sta. Maria Notes ARTICLES 11Dokument5 SeitenAlbano and Sta. Maria Notes ARTICLES 11Su Kings AbetoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5 Love Languages SinglesDokument11 Seiten5 Love Languages Singlestesting13130% (1)

- De Leon v. Abbott - Emergency Motion To Lift StayDokument6 SeitenDe Leon v. Abbott - Emergency Motion To Lift StayjoshblackmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- SSS V BailonRepublic2Dokument8 SeitenSSS V BailonRepublic2russel1435Noch keine Bewertungen

- Noveras V Noveras GR No 188289 Facts - 1Dokument2 SeitenNoveras V Noveras GR No 188289 Facts - 1Mikkoy18100% (1)

- PERSONS AND FAMILY RELATIONS FinalsDokument5 SeitenPERSONS AND FAMILY RELATIONS FinalsAnaSolitoNoch keine Bewertungen

- How to Talk to Anyone: Learn the Secrets of Good Communication and the Little Tricks for Big Success in RelationshipVon EverandHow to Talk to Anyone: Learn the Secrets of Good Communication and the Little Tricks for Big Success in RelationshipBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (1135)

- Briefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndVon EverandBriefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Waitress: The gripping, edge-of-your-seat psychological thriller from the bestselling author of The BridesmaidVon EverandThe Waitress: The gripping, edge-of-your-seat psychological thriller from the bestselling author of The BridesmaidBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (65)