Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Challenges in Implementing The Public Sector Comparator

Hochgeladen von

Husnullah PangeranOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Challenges in Implementing The Public Sector Comparator

Hochgeladen von

Husnullah PangeranCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

This is the authors version published as:

Pangeran, M.H., dan Wirahadikusumah, R.D. (2010). Challenges in Implementing the Public Sector Comparator For Bid Evaluation of PPP Infrastructure Project Investment, Proceedings of the First Makassar International Conference on Civil Engineering (MICCE2010), Makassar, 1229-1239, Hasanuddin University.

Proceedings of the First Makassar International Conference on Civil Engineering (MICCE2010), March 9-10, 2010, ISBN 978-602-95227-0-9

CHALLENGES IN IMPLEMENTING THE PUBLIC SECTOR COMPARATOR FOR BID EVALUATION OF PPPS INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECT INVESTMENT

M. H. Pangeran 1, and R. D. Wirahadikusumah 2

ABSTRACT: The public private partnership (PPP) is indisputable and international experience has indicated that cooperation between the public and private sectors can be a powerful incentive to achieve value for money in infrastructure project development. However, the appropriate risk allocation between the public and private sectors is the key requirement for the achievement of value for money. Public Sector Comparator (PSC) is used for demonstrating potential value for money of the proposed PPP project. PSC enables a financial comparison including costs/gains and risks, and can be an alternative evaluation method which includes risk transfer aspect to facilitate risk negotiation properly. On the other hand, there are challenges in the development of PSC due to controversy regarding manipulation issue, reality of risk transfer in practice, and public sector ability to perform risk management methodology. An extensive literature review was conducted to elaborate some urgency of used PSC and its controversy in practice. It includes some lessons learned in the development of PSC such as the need for structuring risk management application, focusing on priority risk, improving the accuracy of risk-return analysis, realizing the allocation of risk, and enhancing risk management capability. Keywords: Infrastructure project, public private partnership, public sector comparator, value for money, risk, tender

INTRODUCTION The infrastructure refers to the physical assets that are required to provide essential services to society. These include transportation (road, air port, sea port, rail way), energy (oil/gas/electricity generation, transmission and distribution), telecom, and water and sewerage (raw water in-take, treatment process, transmission and distribution). Thus there is a strong relationship between economic growth and infrastructure development, and also the key to reduce poverty, and realize the Millennium Development Goals (MDG). For example in the water sector, the tenth target of MDG aims to reduce by half in 2015 the proportion of people that has presently without access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation. Despite it is widely recognized, the reason that decline of public expenditure because state has limited funds or has other priorities, governments require to search other source of funds to build new and maintain existing infrastructure asset. Traditionally, the provision of infrastructure services was the domain of the public sector. But the recent development shows that the public sector increasingly relies on the private sector involvement to finance, construct, operate and deliver the infrastructure projects and services through a public private partnership (PPP)

1 2

mechanism. Abdel-Aziz (2007) indicates that the first consideration assumes the PPP has the capability to mobilize private capital investment, whereas the second assumes that by having technical expertise and managerial skill, the private sector could be better or more efficient compared to the public sector in providing the similar service. PPP or PFI (private finance initiative) is seen as an effective way to achieve value for money in public infrastructure projects (Li, et, al, 2005). These benefits include introducing competition between prospective private bidders and exploiting the greater efficiency and innovation to be found in the private sector. However, the appropriate risk allocation between public (Government) and private sectors is the key requirement for the achievement of value for money. It is because of tendering PPP project is differs from the traditional project delivery approach. Traditional model of procurement practice (for example, separate design and construction) is typically carried out to detailed specifications by which private contractors following a competitive tender. While PPP is involve contracting between government and private sector under condition of imperfect information (Hurst and Reeves, 2004). The implication is PPP typically more complicated than conventional or traditional project procurement. This is

Phd Student, Bandung Institute of Technology, Bandung, INDONESIA Associate Professor, Bandung Institute of Technology, Bandung, INDONESIA

1229

principally because of the need to anticipate all possible contingencies that could arise in such long-term contractual relationships (Katz, 2006). Therefore it is requires an effective bid evaluation method to represent value for money of the proposed PPP project rather than the cheapest option of the alternatives bid. In order to assess whether a PPP proposed project is the optimal solution, it is necessary to determine whether it provides the best value for money outcome. The procurement authority has a crucial role in managing the procurement process, especially in evaluating the alternatives private bid. In many countries this is done through the development of a public sector comparator (PSC). As a neutral benchmark, PSC is used by procurement authority for demonstrating potential value for money of the proposed PPP project. In general, differ from conventional price bid evaluation only, the PSC enables a financial comparison including costs/gains and risks. Thus, PSC can become an alternative evaluation method which includes risk transfer aspect to facilitate risk negotiation properly. As stated by Eversdijk, et.al (2008), the urgency of PSC is the possibilities to views the potential financial added value, indicates the financial aspects and risks distribution, analysis are project based, setting up a shadow bid in an early stage (before the procurement plan) to reflect on life cycle approach and performance requirements. On the other hand, there are challenges in the development of PSC due to controversy regarding manipulation issue, reality of risk transfer in practice, and public sector ability to perform specific risk management methodology. A systematically literature review was conducted to elaborate some urgency of used PSC and its controversy in practice, including some point as lesson learned. The paper is organized as follows. Part two describes the PPP concept and definition including several forms can be implemented. Part three presents the concept of risk transfer and value for money as the determinants to successful PPP including their relationship with the PSC model. Part four discuss the urgency of PSC for estimating project value for money quantitatively and some its controversy in practice. Part five propose some points as lesson learned to be concern when developing or modeling the PSC. Conclusions of this paper are presented in part six.

PUBLIC PRIVATE PARTNERSHIP There is no universal consensus was used, however, the term of public-private partnership (PPP) can be describes as a spectrum of possible cooperation between public and private entities for the purpose of designing,

planning, constructing, financing and operating an infrastructure project. In this context, the term public sector is generically referred to the Government as public representation. The government may be a division or department of the central government, a minister acting on behalf of the government, and a municipality/ regency or local government, including local state owned enterprise (SOE). Private actors may include private businesses which could be a company or a consortium, as well as non-governmental organizations (NGOs) such as donor agency. PPP (not privatizations for asset sale or divestiture) are contractual relationships. The contract is the heart of the PPP relationship, containing all the duties and obligations of the parties. In these contracts the public sector defines the type and level of service it wants from the private sector. If the private business does not deliver, it is, in effect, in breach of contractual terms and, as a result, may not, for example, receive the full contract payment. In the same way, a properly constructed contract containing appropriate termination clauses negates the necessity for government guarantees (Harris, 2004). In general, the worldwide experience has shown that the PPP, if properly formulated, can provide a variety of benefits to the government. As highlighted by Harris (2004) and Kwak, et.al (2009) that several important benefits of PPP that a PPP can: (i) increase the value for money in infrastructure development and services by providing more-efficient, lower-cost, and reliable services compare with service provided by public sector provider; (ii) helps keep public sector budgets, and especially budget deficiencies; (iii) reduce the project life-cycle costs and project delivering to time (iv) facilitates innovation and spread best practice; (v) construction performance and improve the quality and efficiency of infrastructure services; (vi) the public sector can transfer some risks related to construction, finance, and operation of projects to the private sector partner; (vii) promote local economic growth by development the new business; and (viii) strengthening the national infrastructure. Theoretically the arrangement options of PPP are quite broad and involve a continuum of options ranging from a relatively low level up to high level, such as service contract, management contract, lease contract, BOT (build-operate-transfer) and concession contract (Pribadi and Pangeran, 2007). All options can play a role in bringing private sector expertise and incentives into the project. But it should be noted that the quality of the contract would play an important part in determining the benefits of all options, amongst other things, encompass an appropriate risks allocation between parties. Except for service contracts, a transparent and well considered

1230

regulatory framework is important aspect in securing the benefits of PPP. Management and service contract is the simplest form that does not include any investment from the private sector. The ownership and investment decision is still as the public domain while the private is responsible for management only. Thus, only the operational risk is transferred to the private company. By using this contract type can improve productivity and increase operating or service related performance. The private operator receives a simple fixed-fee and has limited operational responsibility. The duration of contracts is usually 35 years. In management contract, the operator receives a fee that is adjusted by a set of performance benchmarks so as to give the firm an added incentive to achieve specific goals. Lease is medium term of PPP contract and similar to management contracts. But by lease the facilities or infrastructure the private operator takes responsibility for all operation and maintenance functions, including provide working capital, billing and revenue collection. This contract is best to choice where the risks make private finance expensive or impossible to obtain. Among of these risks could include likelihood that tariffs of services would not yield enough revenue to pay for investments, or that subsequent governments would not stick to the rules originally agreed. BOT and similar arrangements (see Table 1), i.e. BTO, BOR, BLO, BLT are a kind of specialized concession in which a private sector firm or consortium finances and develops a new infrastructure project or a major component according to performance standards set by the public sector or government. As stated by Bennet, et.al. (1999), under BOT contract, the private sector finances, builds and operates a new infrastructure facility or system according to the performance standards set by the government. The operations period is long enough to allow the private company to pay off the construction costs and realize a profit, typically 10 to 20 years. The government retains ownership of the infrastructure asset and becomes both the customer and the regulator of the service. BOT is generally issued by governments for the construction of specific facilities, such as bulk supply reservoirs, water treatment plants. BOT typically involve the construction and operation of only one facility and not the entire system (i.e. water treatment plant in the water supply sector). At the highest spectrum, under concession contract, the government awards the private sector partner or concessionaire full responsibility to develop and deliver infrastructure services in a specified area, including all related construction, operation, maintenance, collections and management activities. The concessionaire is also

responsible for any capital investments required to build, upgrade, or expand the system, and for financing those investments out of the tariffs paid by the users. The public sector is responsible for establishing performance standards and ensuring that the concessionaire meets them. Most, this scheme is regulated by an independent regulatory body. Concession scheme is an effective way to attract private finance to fund new construction or rehabilitate existing facilities. A key advantage of the concession is that it provides incentives to the private partner to achieve improved levels of efficiency and effectiveness since gains in efficiency translate into increased profits and return to the concessionaire. The transfer of the full package for operating and financing responsibilities enables the concessionaire to prioritize and innovate as it deems most effective. Table 1 BOT Scheme Variations (Algarni, et.al, 2007)

Type Buildtransferoperate (BTO) Description The transfer of ownership to the government takes place before operation start by the private sponsor. A concession period is given to the sponsor to operate the facility in return for either a certain payment by the government or for the right to collect revenues from users to cover their cost while the facility is owned by the government all through the concession period. This scheme reduces the insurance cost to the sponsor during operation period Similar to the standard BOT agreement except that the private sponsor has the right to request a negotiation for the renewal of the concession at the end of the term The private sponsor possesses the ownership of the facility after completion of construction and leases the facility to the government for longlasting operation (no transfer). The government is responsible for the operation, maintenance, replenishment, and replacement of assets, and pays attention to the interface between construction and operation The private sponsor rents or leases the constructed facility to the government and/or others for a concession period until it recoups its investment before transferring the ownership of the facility to the government

Build-operate and renewal (BOR) Build-leaseown (BLO)

Build-leasetransfer (BLT)

VALUE FOR MONEY, RISK TRANSFER AND PUBLIC SECTOR COMPATOR The PPP procurement is recognized as an effective way of delivering value for money public infrastructure or services. This is the core concept for PPP projects. The term value for money refer to the effective use of public funds on a capital project, can come from the private sector innovation and skills in asset design, construction techniques and operational practices, and also from transferring key risks in design, construction

1231

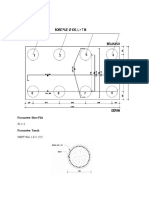

delays, cost overruns and finance and insurance to private sector entities (Grimsey and Lewis, 2002). In other words, a more efficient, lower cost, reliable public service than that of a comparable public service provided by the public sector (Harris, 2004). As mentioned by NSW (2006), values for money drivers in the PPP are: (i) improved risk management; (ii) ownership and whole-of-life costing; (iii) single point of contact (single partys responsibility); (iv) innovation; (v) asset utilization; and (vi) whole-of-Government outcomes. Hence, it is important that the value for money is not always synonymous with the cheaper. Regarding risk transfer, this is a primary objective of PPP project procurement where the public sector partner seeks to divest it self of the risk associated with the delivery and operation of desired public facilities and services (Hardcastle, 2006). However it is should keep in mind that not all project risks are under control by one particular party. For some risks the ability of a particular party to manage the risk, and the costs which it will incur in doing so, will depend to a large extent upon how the other party conducts itself. In these cases, risks need to be shared, and obligations or restrictions need to be imposed on the party that is not best able to manage the risk in order to assist the particular party responsible for managing the risk effectively (Hayfor, 2006). Besides, all involved parties should keep in mind that risk allocation in practice may differ from what it has been planned and originally envisaged. In practice, many countries, i.e. Australia (PV, 2001; DTF WA, 2002), Canada (Industry Canada, 2002), Netherland (Eversdijk et.al, 2008), and Germany (Sachs et.al, 2005) use a PSC model to helps government test whether a private investment proposal offers value for money compared with the most efficient form of public provision. Based on the literature can be said that PSC are generally categorized into four core elements as raw PSC (base costs), transferable risk (to the private sector), retained risk (by Government) and competitive neutrality (no competition). Figure 1 provides an illustration the components of a PSC with the components of risk separately identified, and shows how it can be used to compare against PPP bids from the private sector. The Raw PSC should provides a base costing under the public procurement method including capital and operating costs, and represent a full and fair estimate of all of the costs of delivering publicly the same volume and level of performance, service and residual asset value that is required from the private sector under the PPP alternative. The costs will include (i) preliminary set-up and planning work, approvals and permits; (ii) costs to achieve any efficiencies and innovation; (iii)

design and capital procurement, including replacement; (iv) opportunity cost of using existing assets; (v) management and facility overheads; (vi) operating costs, including maintenance, consumables, contracted services, staff, utilities, etc.; (vii) any decommissioning costs at the end of the project (Grimsey and Lewis, 2005).

Fig. 1 Public Sector Comparator and value for money

As discussed before, the optimal allocation of risk is the key objective of all PPP project procurement and the value of transferable risk needs to be included in the PSC. Also, the transfer of risk is a key determinant of value for money in PPP, and one that may need to be updated as negotiations proceed, to allow for variations in risk allocation. Therefore, a detailed risk register is required including the analyzing in terms the impact to project financial. Since not all project risks are under control by one particular party, hence, any risk that is not transferred under the PPP contract is a retained risk by Government. The value for retained risk needs to be included in the PSC using the same methodology as applied for transferred risks. Determining the value of risks using historic and current data as benchmarks is highly dependent on the availability of such data and countries vary as to the extent to which relevant data have been collated and made available (Grimsey and Lewis, 2005). Competitive neutrality adjustments remove any net competitive advantages that accrue to government business by virtue of its public ownership (PV, 2001). This allows a fair and equitable assessment between a PSC and bidders. In practice, the procurement team should review all the circumstances surrounding the project and the market for potential bidders, to identify any material advantages or disadvantages peculiar to government under a public sector delivery method. Then, the initial value for money test is accomplished by comparing the risk-adjusted PSC Model with the riskadjusted PPP Model. The NPC is compared from both models, and the one that brings less NPV is considered as providing more value for money.

1232

URGENCY AND CONTROVERSY OF PSC PSC generally aim to provide a reference point for comparing the cost of public delivery of infrastructure and ancillary services with other procurement methods, including PPP. PSC therefore becomes an essential tool for determining whether a PPP procurement option should be considered, and also during the evaluation of expressions of interest and final bids (DTF WA, 2002). A key objective in developing a PSC is that it provides a reliable means of demonstrating value for money and in terms of whole of life costs imparts confidence in the assessment process. If private sector bids can demonstrate value for money against the PSC, then private sector provision should be pursued. Grimsey and Lewis (2005) stated that fashioning the PSC performs the following roles: (i) promotes full costing at an early stage in project development, (ii) provides a key management tool during the procurement process by focusing attention on the output specification, risk allocation and comprehensive costing, (iii) provides a means for testing project value for money, (iv) provides a consistent benchmark and evaluation tool, and (v) encourages competition by generating confidence in the market that financial rigor and probity principles are being applied. Despite its urgency well recognize, the use of the PSC has been criticized for leaning too much on quantitative measuring and thereby excluding broader societal concerns that are difficult to quantify and force the participants to work on a contract based on cool cash instead of trying to take care of long term considerations (Kristiansen, 2009). Some of critiques that PSC is tend to manipulation because of procurement team want to prove value for money by exaggerating innovation and benefits of a PPP option by ignoring the problems experienced by current PPP schemes, whilst assuming limited scope for innovation and efficiency improvements in the public sector. They also frequently underestimate the full cost of the PPP option. In this case costing was included without evidence to support them. Therefore not surprisingly, the PSC regularly shows PFI projects to provide value for money. The PSC has been described as an invention, artificial and biased. In their study regarding value for money of PFI project for NHS hospital in UK, Pollock, et.al (2002) indicates that the function of risk transfer is tend to disguise the true cost of PFI and to close the difference between private finance and the much lower cost of conventional public procurement and private finance. Even after this manipulation, however, the difference between the PSC and the PFI is marginal, in many cases less than 0.1%.

The study also found that there is no standard method for identifying and measuring the values of risk, and the UK government has not published the used methods. There was little clarity in how risks were measured, and in over two thirds of the business cases for PFI schemes, the risk could not be identified. A similar argument by Leigland and Shugart (2006) that much of PSC depends on subjective judgment, and small adjustments for risk can have dramatic effects on cost estimates. Theoretically PSC may include risk-adjusted cost estimate, however, it is not actually transferred in the contract. Hall (2008) indicates that most PPP project assessments, however, only consider whether the PPP is economically feasible for a private consortium. For example (see Friedrich and Reiljan, 2007), a state audit office report in Estonia has said that Estonian public authorities do not use proper PSC in assessing the relative attractions of PPP. The consequences of a PPP have been assessed by primitive investment accounting, measuring the benefits in terms of cost savings and profits. As a result non-transparent and unfavorable contracts have been signed. The contracts have included inflated costs, due to excessive profit margins, risk premium, or depreciation allowances. Proper evaluations would have led to many PPP being rejected (studies in Estonia have shown that long-term PPP cost 25% more than public ownership). The transfer of risk is the critical element in proving value for money of proposed PPP project. However, Pollock, et.al (2002) indicates that risk is the most difficult part in the development of PSC as well as risk transfer requires the ability and special expertise of procurement authority in performing risk management methodology.

LESSONS LEARNED AND DISCUSSIONS The PPP is indisputable and international experience has indicated that cooperation between the public and private sectors can be a powerful incentive to improve the quality and efficiency of public services, and a mean of public infrastructure financing. However, it is important to understand that PPP does not provide an automatic solution to public infrastructure problems. The proposed project must show the value for money by which it can be reached if risk is allocated in efficient manner. As a neutral benchmark, PSC estimating value for money quantitatively and also provides a rational basis to allocate the risk appropriately. Despite the urgency of PSC is well recognized, modeling the PSC is required a structured application of risk management and adequate capability of procurement team in performing

1233

risk management methodology. The following are some points to be considered in the development of PSC in tendering PPP infrastructure project. Structuring Risk Management Application Risk management is the key input into the PSC to assess quantitatively the potential value for money of a PPP proposal. If the project reach financial closure and project is executed, then risk management will continue to play a substantial role in project management over the life of the long-term contract. The development of PSC model is basically built from a structured application of risk management processes. According to PMI (2004) and Australian Standards (2004), the key step of risk management process is at least consisting identification of risk, assessment both qualitatively and quantitatively, and risk response planning. In this case risk management plan is optional. A structured application is important because only a systematic risk management process allows early detection of identified risks and encourages the PPP stakeholders to understand the risks, as well as take measures to identify available risk mitigation and appropriate distribution. For example, Pribadi, et.al (2006) develop a risk management approach integrating both qualitative and quantitative methods in assessing the risk and return investing water supply infrastructure through PPP concession contract. The proposed model, namely Integrating Qualitative and Quantitative (IQQ) Risk Analysis consists of four main stages as identifying potential risks, determining priority risks, analyzing the impact of priority risks, and reporting the results. Qualitative risk analysis is conducted using risk rankingat-confidence level (RR-CL) method to determine the priority risks, which are subsequently analyzed using a Latin hypercube sampling cash flow simulation. Related to the model, following discussion provide a rationale on why we should be focus on priority risk before perform a quantitative risk analysis. Focusing On Priority Risk It is essential to evaluate all of the potential risks throughout the whole life of the project. All involved parties must pay particular attention to the procurement process to ensure a fair risk allocation. However, there are many factors can be identified as risk by which if they occur can give an adverse effect to the project. Table 1 contains a list of potential risk in PPP infrastructure project.

Table 1 Potential Risk in PPP Infrastructure Project (Kwak, et.al, 2009)

Risk category Political Risks Risk Factor Expropriation, reliability and creditworthiness of the government Change in law and government policies Political opposition Corruption Delay in approvals Political force majeure events Unfavorable economy in the host country Rate of return restrictions Lack of credit worthiness Inability to service debt Bankruptcy Complex financial structure of PPP projects Lack of guarantees Financing risks Loan ability Fluctuation of the inflation rate, interest rate, foreign currency exchange rate Unfavorable international economy Land acquisition and compensation Construction cost overrun Construction time delay Material/labor availability Project site conditions Contractors failure Construction force majeure events Operation and maintenance cost overrun Operators incompetence and low operating productivity Availability of material Force majeure events Insufficient revenue Government restriction of profit and tariff Inaccurate pricing and demand estimate Fall of demand The competition risks Force majeure events Prejudiced and unfair process of awarding the project Host-countrys interference in choosing subcontractors Overprotective control/ supervision by the host government Disapproval of guarantees by the government Change of hostcountrys fiscal regime Change of host-countrys consideration of the projects scope Noncooperation between public agencies Actions or omissions of the public authorities that prevent the project to be completed Unsteady legal and regulatory framework Poor legislation Non-enforcement of legislation Lack of a stable project agreement Vague and inconsistent clauses and specifications and inaccurate phasing Language barrier for the contract Breach of contract provisions Revision of the contract clauses Unanticipated change of the concessionaire scheme Lack of confidentiality and trust in the concession company Risks of early termination Legal force majeure events

Financial Risk

Construction Risks

Operation and Maintenance Risks Market and Revenue Risks Legal Risks

In order to formulate an appropriate risk response plan, the risks must not only be identified, but must be assessed to determine what risk is priority to be focused by involved parties. The importance of risk prioritization is that the organization can improve the projects performance effectively by focusing on high-priority risks (PMI, 2004). Therefore a qualitative risk analysis is conducted before further action to assess risk in-depth quantitatively. As stated by Stam, et. al (2003), the use of qualitative risk analysis is aims to provide a quick and clear picture of the identified risks, one that is easily understandable for everyone, whereas by performing quantitative risk analysis, the effect of the measures may be mapped out more clearly. In this context modeling

1234

quantitative risk analysis is corresponding with project value for money estimation. In practice, it may use forms of analysis that range from simple qualitative methods to more sophisticated semi-quantitative approaches. As a simple method, qualitative analysis is based on nominal or descriptive scales for describing the likelihoods and consequences of risks. This is particularly useful for an initial review or screening or when a quick assessment is required. In advance level, a semi-quantitative analysis may extend the simple qualitative analysis process by allocating numerical values to the descriptive scales. The numbers are then used to derive quantitative risk factors. According to PMI (2004) some qualitative risk analysis technique are risk probability and impact assessment, risk probability and impact matrix, and risk urgency assessment. Risk probability assessment investigates the likelihood that each specific risk will occur, whereas risk impact assessment investigates the potential effect on project objectives such as time, cost, and quality or performance, including both negative effects for threats and positive effects for opportunities. The probability and impact matrix technique can be used to classify risks according to their individual significance. In case identified risk requiring near-term responses may be considered more urgent to address. Improving The Accuracy Of Risk-Return Analysis The financial evaluation of a privatized infrastructure project is challenging due to complexity and a variety of risks and uncertainties related to project finance (Zhang, 2005). Risk management discipline is needed to protect the benefit or profit by reducing the possible losses or damage before they occur. Traditionally, there are ways to evaluate financial viability of the proposed project, i.e. payback period, discounting payback period, net present value (NPV), and internal rate of return (IRR) methods. However, the common uses are based on the assumption that the project cash flow is certain, called deterministic approach. In reality, the output of a risk analysis is not a single-value but a probability distribution of all possible expected returns. In this case the prospective investor is therefore must be provided or supported with a complete risk and return profile of the project showing all the possible outcomes that could result from the decision to stake his money on a particular investment project (Savvides, 1994). However, a common mistake in quantitative risk analysis is assuming that chance events are independent (Schuyler, 2003). In this context, a chance (risk or uncertainty) is related to one or more other chance events. One of the reasons to might observe a correlation between observed data is that there is a

logical relationship between two (or more) variables (Vose, 1996). Tanaka, et.al (2005) also suggestion to account for any correlation effect between uncertain variables that will lead to build realistic models. In practice, the quantification of the correlation effect between variables can be found in two alternative ways: modeling the correlation between the variables if data is available; and estimated from the subjective opinion of experts if data is not available. Generally, most of risk analysis software products now offer a facility to correlate probability distribution within a risk analysis model using rank order correlation. The technique is very simple, requiring only that the analyst nominates the two distributions that are to be correlated and a correlation value between 1 and +1. This coefficient is known as Spearmans rank order correlation coefficient. But the use rank order correlation to model dependencies that only have a small impact on models results (Vose, 1996). As alternative, correlation matrices as an extension of the rank order correlation coefficient method can use because it enables to correlate several probability distribution together. In practice, the rank order correlation coefficients are input into the cross-referenced positions in the matrix. Each distribution must clearly have a correlation of 1.0 with itself so the top left bottom right diagonal elements are all 1.0. Furthermore, because the formula for the rank order correlation coefficient is symmetric, as explained, the matrix elements are also symmetric. As an example, Pangeran and Pribadi (2009) develop a practical quantitative risk analysis model which can be used to evaluate an infrastructure PPP project risk. The model is developed based on a stochastic/probabilistic approach for uncertain project cash flow. The input used in the simulation model consisting of financial risk variables such as fluctuation of interest rate, exchange rate and inflation rate are considered as correlating factors, analyzed using a correlation matrix. An exercise by using a case study indicates that there is a significant effect of including relationship between correlated components to the final model output and on their distribution shape. The use of correlation input can improve the accuracy by reducing unnecessary possibility that project NPV will fall within range value generated by the model without correlation input consideration. Thus, the model offers an ability to show the project return and risk profiles as close as possible to the project situation, as it considers the real field project behavior in the analysis process.

1235

Realizing The Allocation Of Risk As widely discussed, the PPP principle is risk should be allocated to the partner best able to manage it in a cost effective manner. Also, effective allocations of risk refer to lower financial costs and hence added value for the PPP when compared with traditional project delivery method. Abdel-Aziz (2007) suggested that the allocation should, however, be assessed in term ultimate users. The risk that the private sector are in a better position to control that the government include design risk, construction risk including cost overrun and completion time, and future operation and maintenance cost overruns. On the other hand, the risk, for example, a change of law risk, should be retained by the government. Some researchers has been studied the perceived of allocation risk in PPP infrastructure project. As an example, Li, et.al, (2005) identify three levels of risk in PPP infrastructure project, namely macro, meso, and micro level. Macro level risks are sourced exogenously, i.e. they are external to the project itself, or beyond the system boundaries of the project. Meso level risks arise endogenously, i.e. internally at the project level through the processes of the project itself. The micro level risks is more difficult to define, but represents the risks present in stakeholder relationships formed in the project procurement process, and which arise mainly through the inherent differences between the public and private sectors in ethos and contract management approach. Then, they explore preference in risk allocation and the results shows that macro and micro level risks should mainly be allocated to the public sector or shared with the private sector; while the majority of meso level risks should be allocated to the private sector. Based on literature review, Shen et al. (2006) was identified a number of risks affecting PPP infrastructure projects. Then, they use the Hong Kong Disneyland project as a case study for demonstrating which risks would be most suitably allocated to each party involved. The study concluded that inexperienced private partner risk, site acquisition risks, and legal and policy risk should be allocated to the public sector. Whereas the risk should be transfer to the private partner are the design and construction risks, operation risks and industrial action risks. Lam, et. al. (2007) was identified several criteria as a key for risk allocation. It is include the whether the party is able to foresee the risk, to assess the possible magnitude of the consequences of the risk; to control the chance of the risk occurring, to manage the risk in case it occurs, to sustain the consequences if the risk occurs. Another criterion is whether the party will benefit from bearing the risk, and the premium charged

by the risk-receiving party is considered reasonable and acceptable for the owner. Although the appropriate risk allocation is well recognized as the key for successful PPP procurement, but in some cases, the practice of risk transfer is still problematic. In this context risk transfer is more apparent than real. Even though it is possible to list all identified risks, but it is still far from easy to ensure that the risks identified even high priority risk will be transferred in practice via the contract, and even when transferred, it is not always possible to enforce the contract. Therefore it must bear in mind that the contract management is not just a legal contest. It was to ensure the delivery of public services will be determined by all the components of the project, including the designing, planning, constructing, financing and operating the infrastructure. Especially in Indonesia, the Presidential Decree No.67/2005 has contains provisions which must be included in cooperation agreements between the Government and private partners. Some substances related to business competition such as tariffs (price) determination, service performance standard, sanctions and supervision mechanism on private partners must be stipulated in such agreements, and the right and obligations of the parties (including allocation of risks). Generally, it is provide a clear mechanism to anticipate various anticompetitive behaviors especially by private partners as the holders of concession rights. Enhancing Risk Management Capability Indeed, the arrangement of risk sharing between parties should provide an incentive for the private sector partner to perform their business as efficiently as possible. However, this is not easy given the technical, legal, social, political and economic complexity of infrastructure projects make broad range of risk and uncertainties in frame of long-term PPP contract. Too often, risks are under estimated and allocated to parties without the knowledge and capabilities to manage them effectively, resulting increased costs, project delays and services which fail to deliver value-for-money (Ng and Loosemore, 2006). Therefore, successful implementation of a PPP in infrastructure development requires the availability and ability of diverse skills and expertise in procurement, legal, and financial management (AbdelAziz, 2007). However, as indicated by Pollock, et.al (2002), there is no standard method for identifying and analyzing risk, the risk management is the most difficult in value for money methodology and requires high capability to perform risk management of the public sector, especially procurement authority. There is also a

1236

fact that government may have limited expertise in certain aspects of a PPP transaction. There are too many government and local authority organizations involved in PPP projects (Roe and Craig, 2004). In this case expertise is diffuse and often dissipated. Specialist professional PPP units within each of the major spending departments should be charged with the authority and accountability for developing sector-specific PPP expertise. This means that public sector expertise, especially in risk management field needs to be enhanced. Other ways, the government may obtain the expertise from outside (i.e. risk management consultant) for advisory services in areas where they have limited expertise. Especially to the PPP agency, the benefits of used risk management are (AG DFA, 2006) (i) enhanced performance delivery (i.e. early identification, structured and systematic consideration of risks, effective risk allocation and monitoring in all areas, which contributes to greater likelihood of success in achieving project scope, innovation and KPIs or Key Performance Indicators); (ii) an accountable platform for project planning (i.e. assistance in developing criteria for evaluating tender responses; prioritization for the effective allocation of resources and improved value for money through appropriate and efficient risk allocation and management, reduction in project costs through development of a standardized process of allocating risk); (iii) a robust decision making process (i.e. improved decision-making through development of a comprehensive PSC model including the impact of project risks; placing an agency in a better position to negotiate a project contract through gaining a better understanding of the project risks, informed choice on preferred project partners; and detailed and measured due diligence process for projects strategic and operational stages); and (iv) positive return on taxpayers investment, hence, increased government confidence in applying PPP infrastructure project to achieve better procurement outcomes.

requirements. PSC enables a financial comparison of costs/gains and risks. Thus, the PSC can provide a rationale basis and facilitate risk negotiation properly to the parties involved. On the other hand, there are challenges in the development of PSC due to controversy regarding manipulation issue, reality of risk transfer in practice, and the ability of public sector to perform risk management methodology. This paper discuss some points as lesson learned such as the need of structured application of risk management process and technique in the development of PSC, by focusing only on priority risk and improving the accuracy in risk-return analysis for value for money estimation. Although the appropriate risk allocation is well recognized as the key for value for money achievement, but in practice is still problematic because of it is more apparent than real. Despite the principle that risk must be transferred and allocated to the party that best able to bear and manage the risk for efficiency and affectivity in infrastructure development, it must be understand that contract management is not just a legal contest. In this case risk must be transferred in practice via the contract, and even when transferred, there must be guarantee to enforce it. Although, risk management is the most difficult in value for money methodology which requires high capability to perform, there is no standard method for identifying and analyzing risk. This means that public sector expertise in risk management field needs to be enhanced. Other ways, the government may obtain the expertise from outside (i.e. risk management consultant) for advisory services in areas where they have limited expertise.

REFERENCES Abdel-Aziz, A.M. (2007). Successful Delivery of PublicPrivate Partnerships for Infrastructure Development, J. of Const. Engrg and Management, 133 (12), 918931. AG DFA Australian Government Department of Finance and Administration (2006). Public Private Partnerships: Risk Management, Commonwealth of Australia. Algarni, A.M, Arditi, D., and Polat, G. (2007). BuildOperate-Transfer in Infrastructure Projects in the United States, J. of Const. Engrg and Management, 133 (10), 728-735. Bennet, E., Grohmann, P., and Gentry, B. (1999). Public-Private Partnerships for the Urban Environment: Options and Issues, PPPUE Working Paper Series Vol. I, UNDP & Yale Univ., New York

CONCLUSIONS The PPP is an effective way to achieve value for money in infrastructure development. Value for money is examined by compare the PPP proposal and the Public Sector Comparator (PSC) as a neutral benchmark. The urgency of PSC is the possibilities to views the potential financial added value of the proposed project, indicates the financial aspects and risks distribution, analysis are project based, setting up a shadow bid in an early stage (expected value for money before the procurement phase) to reflect on life cycle approach and performance

1237

DTF WA Department of Treasury and Finance West Australia (2002). Partnerships for Growth: Policies and Guidelines for Public Private Partnerships in Western Australia, Department of Treasury and Finance, Perth. Eversdijk, A., Beek, P., and Smits, W. (2008). The Public Private Comparator: A Dutch Decision Instrument in PPP Procurement, Proc. of 3rd International Public Procurement Conference. Friedrich P. and Reiljan J. (2007). An Economic Public Sector Comparator for Public Private Partnership and Public Real Estate Mangament. ASPE Conference, St Petersburg. Grimsey, D. and Lewis, M.K. (2002). Evaluating the Risks of Public Private Partnerships for Infrastructure Projects, Int. J. of Project Management, 20, 107-18. Grimsey, D. and Lewis, M.K. (2005), Are Public Private Partnership Value for Money? Evaluating Alternative Approaches and Comparing Academic and Practitioner View. Accounting Forum (29) 345 378 Hall, D. (2008). PPPs in the EU: A Critical Appraisal, ASPE Conference, St. Petersburg Hardcastle, 2006). Hardcastle, C. (2006). The private Finance Initiative Friend or Foe, Proc. of the Int. Conference in the Built Environment in the 21st Century, Selangor. Harris, S. (2004). Public Private Partnerships: Delivering Better Infrastructure Services, The 2004 IDB Infrastructure Conference Series, Washington. Hayford, O. (2006). Successfully Allocating Risk and Negotiating a PPP Contract, 6th Annual National Private Public Partnerships Summit. Hurst, C. and Reeves, E. (2004). An Economic Analysis of Irelands First Public Private Partnership, The Int. J. of Public Sector Management; 17, 4/5, 379-388. Industry Canada (2002). The Public Sector Comparator: A Canadian Best Practices Guide, Services Industries Branch, Ottawa. Katz, D. (2006). Financing Infrastructure Projects: Public Private Partnerships (PPPs), New Zealand Treasury Policy Perspectives Paper 06 (02). Kristiansen, K. (2009). PPP in Denmark Are Strategic Partnerships between the Public and Private Part a Way Forward?, Proc. of Symposium CIB TG72, Univ. of Hongkong. Kwak, Y.H., Chih, Y.Y., and Ibbs, C.W. (2009). Towards a Comprehensive Understanding of Public Private Partnerships for Infrastructure Development, California Management Review, 51 (2), 51-78. Lam, K.C, Wang, D, Lee, P.T.K and Tsang, Y.T. (2007). Modelling Risk Allocation Decision in Construction Contracts, Int. J. of Project Management, 25, 485493.

Leigland, J., dan Shugart, C. (2006): Is the Public Sector Comparator Right for Developing Countries?, Gridlines, Note No. 4, PPIAF. Li, B, Akintoye, A, Edwards, P.J and Hardcastle, C (2005), The Allocation of Risk in PPP/PFI Construction Projects in the UK, Int. J. of Project Management, 23 (1), 25-35. Ng, A. dan Loosemore, M. (2006). Risk Allocation in the Private Provision of Public Infrastructure, Int. J. of Project Management, 25, 66-76. NSW New South Wales Government (2006). Working with Government: Guidelines for Privately Financed Projects, State of New South Wales through NSW Treasury, Sydney. Pangeran, M,H., and Pribadi, K,S. (2009). Financial Risk Analysis Using Matrix Correlation for Public Private Partnership Infrastructure Project Investment Evaluation, Proc. of The 1st Int. Conference on Sustainable Infrastructure and Built Environment in Developing Countries, Bandung. PMI Project Management Institute (2000): A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, Philadelphia, USA. Pollock, A.M., Shaoul, J., dan Vickers, N. (2002): Private Finance and Value for Money in NHS Hospitals: A Policy in Search of Rationale?, British Medical Journal, 324, 1205-1209. Presidential Decree Republic of Indonesia No.67/2005 concerning Public Private Partnership (PPP) in Infrastructure Provision Pribadi, K,S. and Pangeran, M,H. (2007). Important Risk on Public-Private Partneship Scheme in Water Suply Investment in Indonesia, Proc. of The 1st Int. Conference of European Asian Civil Engineering Forum (EACEF), Jakarta. Pribadi, K,S., Soekirno, P., and Pangeran, M,H. (2006). Integrating Qualitative and Quantitative Risk Analysis for Investment in Public Private Partnership Scheme for Water Supply in Indonesia, Proc. of the Tenth East Asia-Pacific Conference on Structural Engrg. and Const. (EASEC-10), Bangkok. PV Partnership Victoria (2001). Public Sector Comparator Technical Note, The Secretary Department of Treasury and Finance, Melbourne. Roe, P. and Craig, A. (2004). Reforming the Private Finance Initiative, Centre for Policy Studies, London. Sachs, T, Elbing, C., Tiong, R.L.K, and Alven, H.W. (2005). Efficient Assessment of Value for Money (VFM) for Selecting Effective Public Private Partnership (PPP) Solutions A Comparative Study of VFM Assessment For PPPs in Singapore and Germany, Proc. of The Queensland Univ. of Tech. Research Week Int. Conference, Brisbane.

1238

Savvides, Savvakis. (1994). Risk Analysis in Investment Appraisal, Project Appraisal, 9 (1), 3-18. Schuyler, J. (2001). Risk in Decision Analysis in Projects, 2nd Ed., Project Management Institute, Pensylvania, USA. Shen, L.Y, Platten, A., and Deng, X.P. (2006). Role of Public Private Partnerships to Manage Risks in Public Sector Projects in Hong Kong, Int. J. of Project Management, 24, 587-594. Stam, D., Lindenaar, F., Kinderen, S., and Bunt, B. (2003). Project Risk Management: An Essential Tool for Managing and Controlling Projects, Kogan Page, Ltd. London Sterling VA.

Standards Australia (2004). Risk management AS/NZS 4360:2004. Tanaka, D.F., Ishida, H., Tsutsumi, M., Okamoto, O. (2005). Private Finance for Road Projects in Developing Countries: Improving Transparency through VFM Risk Assessment, J. of the Eastern Asia Society for Transp. Studies, 6, 3899-3914. Vose, D. (1996). Quantitative Risk Analysis: A Guide to Montecarlo Simulation Modeling, John Willey & Sons, Canada. Zhang, X. Q. (2005). Financial Viability Analysis and Capital Structure Optimization in Privatized Public Infrastructure Projects, J. of Const. Engrg. and Management, 131 (1) 3-14.

1239

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Daily Report DED (20210529)Dokument11 SeitenDaily Report DED (20210529)My pouNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ansys AnalysisDokument12 SeitenAnsys AnalysisAmbaliyaSanjayNoch keine Bewertungen

- PLAXIS2DCE V21.00 02 Reference 2DDokument576 SeitenPLAXIS2DCE V21.00 02 Reference 2DHasnat QureshiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sadt HT 225a Manual Book For UserDokument20 SeitenSadt HT 225a Manual Book For UserWansa Pearl FoundationsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Modul 10 - EstimasiBiaya & Rekayasa Ekonomi - Ali SunandarDokument10 SeitenModul 10 - EstimasiBiaya & Rekayasa Ekonomi - Ali SunandarAndi Ra Mi'rajNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lampiran I (Bar Bending Schedule/Bestat)Dokument77 SeitenLampiran I (Bar Bending Schedule/Bestat)aerudzikriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analisa PedestalDokument22 SeitenAnalisa PedestalAnisha MayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Perhitungan Concrete Prestressed Box Girder: Kentungan Fly Over, Yogyakarta 17.00Dokument99 SeitenPerhitungan Concrete Prestressed Box Girder: Kentungan Fly Over, Yogyakarta 17.00Gusti SudikaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Basic Price 2019Dokument30 SeitenBasic Price 2019Adited MlnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Laporan WamenaDokument40 SeitenLaporan WamenaxryosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3-3 Working With SpreadsheetsDokument34 Seiten3-3 Working With Spreadsheetscrystal macababbadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Review Desain Jembatan Overpass Balaraja AbutmentDokument15 SeitenReview Desain Jembatan Overpass Balaraja AbutmentAkmal Syarif100% (1)

- Balok GirderDokument40 SeitenBalok GirdertriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cross SectionDokument87 SeitenCross Sectionrobynson banikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Associated Flow RulesDokument10 SeitenAssociated Flow RulesShahram AbbasnejadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Perhitungan Pondasi Caisson - Proyek Jembatan Simpang Jam BatamDokument6 SeitenPerhitungan Pondasi Caisson - Proyek Jembatan Simpang Jam BatamFawwaz AidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dimensi AbutmentDokument4 SeitenDimensi AbutmentMuhammad HamzahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Perhitungan Teknis Dan GambarDokument8 SeitenPerhitungan Teknis Dan GambarIndraHoedaya100% (1)

- Supplemento Programación LinealDokument9 SeitenSupplemento Programación Linealmay_soulNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analisa Software Geo5Dokument6 SeitenAnalisa Software Geo5nexton86Noch keine Bewertungen

- Perhitungan Bore PileDokument5 SeitenPerhitungan Bore PileFitri Yani100% (1)

- Kapasitas Daya Dukung Tiang Pancang Berdasarkan Data SondirDokument1 SeiteKapasitas Daya Dukung Tiang Pancang Berdasarkan Data SondirIsti HaryantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 17-1 Usage of Recycled Tyre MCRJ Volume 29, No.3, 2019 PDFDokument10 Seiten17-1 Usage of Recycled Tyre MCRJ Volume 29, No.3, 2019 PDFNor Intang Setyo HNoch keine Bewertungen

- Desain AbutmentDokument75 SeitenDesain AbutmentLouce PatriciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final Resume Hammer TestDokument7 SeitenFinal Resume Hammer Testheni luthfiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Skripsi Tanpa Bab PembahasanDokument64 SeitenSkripsi Tanpa Bab PembahasanMuhammad Azhar100% (1)

- International Journal of Engineering TechnologyDokument8 SeitenInternational Journal of Engineering TechnologykumarcvNoch keine Bewertungen

- Model 11 DepreciationDokument15 SeitenModel 11 DepreciationAldi GunawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tugas 3 MPKDokument10 SeitenTugas 3 MPKAmira MaryanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mkji 1997Dokument608 SeitenMkji 1997Zerry FariandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CSTDokument33 SeitenCSTVasthadu Vasu KannahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gouw 2014Dokument23 SeitenGouw 2014Lissa ChooNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7 Design of Deep Flexural MemberDokument56 Seiten7 Design of Deep Flexural MemberSarah SpearsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teknik Perbaikan Dan Perkuatan StrukturDokument176 SeitenTeknik Perbaikan Dan Perkuatan StrukturTomi Kazuo100% (1)

- Prilaku Balok Kastela Dengan Elemen HinggaDokument7 SeitenPrilaku Balok Kastela Dengan Elemen HinggaFiqri AnraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Daftar NTUSTDokument5 SeitenDaftar NTUSTAbdul Aziz0% (1)

- Perhitungan Penurunan Menggunakan AllpileDokument1 SeitePerhitungan Penurunan Menggunakan AllpileSu NarkoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tekcon - Spun Piles PropertiesDokument10 SeitenTekcon - Spun Piles PropertiesChung Yiung YungNoch keine Bewertungen

- Building Construction ReportDokument51 SeitenBuilding Construction ReportAndrew Chee Man ShingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analisa Struktur Iv Soal No.2 Truss 2D: Properti Es A E 1 0,0 02 2,1 E7 P 20 TonDokument12 SeitenAnalisa Struktur Iv Soal No.2 Truss 2D: Properti Es A E 1 0,0 02 2,1 E7 P 20 TonWira d mNoch keine Bewertungen

- Beton FastrackDokument11 SeitenBeton FastrackTeugeuraBaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Larssen Sheet Piles PalPile 341015478Dokument1 SeiteLarssen Sheet Piles PalPile 341015478Moataz M. M. RizkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Progress Jurnal LCA Kayu Lapis - Impact AssesmentDokument7 SeitenProgress Jurnal LCA Kayu Lapis - Impact AssesmentIsandre FajarrachmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Boring Log: Testana Engineering, IncDokument1 SeiteBoring Log: Testana Engineering, IncetwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Soft Copy Laporan Sandcone Gudang - JIIPEDokument2 SeitenSoft Copy Laporan Sandcone Gudang - JIIPEardaloevera_63818328Noch keine Bewertungen

- Welcome To The Presentation On "One Way Slab Design: Md. Asif Rahman 10.01.03.108 Dept. of CeDokument29 SeitenWelcome To The Presentation On "One Way Slab Design: Md. Asif Rahman 10.01.03.108 Dept. of CeAmit GuptaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Perhitungan Pondasi Sumuran: Input Data Disain AwalDokument1 SeitePerhitungan Pondasi Sumuran: Input Data Disain AwaldeddiiskandarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contoh Soal TRUSS 2DDokument13 SeitenContoh Soal TRUSS 2DM. Yoga Ali AkbarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gempa03 Pengukuran GempaDokument55 SeitenGempa03 Pengukuran GempaFarid MarufNoch keine Bewertungen

- Regel Gigi AnjingDokument3 SeitenRegel Gigi AnjingMultimediaWarnetMmnetNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jotun Jota Ep Mastic 66Dokument4 SeitenJotun Jota Ep Mastic 66Abi PutraNoch keine Bewertungen

- PRISM For Earthquake Engineering A Program For Seismic Response Analysis of SDOF SystemDokument13 SeitenPRISM For Earthquake Engineering A Program For Seismic Response Analysis of SDOF SystemPrabhat KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Construction and Building Research Conference of The Royal Institution of Chartered SurveyorsDokument15 SeitenThe Construction and Building Research Conference of The Royal Institution of Chartered SurveyorsAnnisa HasanahNoch keine Bewertungen

- PPP Bankable Feasibility Study: A Case of Road Infrastructure Development in North-Central Region of NigeriaDokument7 SeitenPPP Bankable Feasibility Study: A Case of Road Infrastructure Development in North-Central Region of NigeriainventionjournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transaction Cost Analysis/ Summary and ConclusionDokument8 SeitenTransaction Cost Analysis/ Summary and ConclusionJanine Prelle DacanayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Public Private PartnershipsDokument5 SeitenPublic Private PartnershipsFaisal AlawiNoch keine Bewertungen

- IATSS Research: Xueqing Zhang, Shu ChenDokument10 SeitenIATSS Research: Xueqing Zhang, Shu ChenZulfadly UrufiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Report On Ex-Post Risk Analysis in Public Partnership ProjectsDokument10 SeitenReport On Ex-Post Risk Analysis in Public Partnership ProjectsswankyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Risck Analysis and Allocation in Public Private Partnership ProjectsDokument10 SeitenRisck Analysis and Allocation in Public Private Partnership Projectsmarri likhithaNoch keine Bewertungen

- PPPsuccess StoriesDokument114 SeitenPPPsuccess StoriesRoberto Gonzalez BustamanteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impact and Sustainability of Community Water Supply and Sanitation Programmes in Developing CountriesDokument15 SeitenImpact and Sustainability of Community Water Supply and Sanitation Programmes in Developing CountriesHusnullah PangeranNoch keine Bewertungen

- 92mengesha AdmassuDokument10 Seiten92mengesha AdmassuHusnullah PangeranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Proceedings PDFDokument14 SeitenProceedings PDFspratiwiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civil 522 Project and Construction Economics: Fall 2004 Course OutlineDokument4 SeitenCivil 522 Project and Construction Economics: Fall 2004 Course OutlinespratiwiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Model Pemilihan Skema Kerjasama Pemerintah Dan SwastaDokument11 SeitenModel Pemilihan Skema Kerjasama Pemerintah Dan SwastaHusnullah PangeranNoch keine Bewertungen

- High Impact Presentation SkillsDokument5 SeitenHigh Impact Presentation SkillsMohd AqminNoch keine Bewertungen

- ISO9001 2008certDokument2 SeitenISO9001 2008certGina Moron MoronNoch keine Bewertungen

- Technical DataSheet (POWERTECH社) -55559-9 (Motormech)Dokument2 SeitenTechnical DataSheet (POWERTECH社) -55559-9 (Motormech)BilalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Risk Solver Platform ReferenceDokument247 SeitenRisk Solver Platform Referencemj_davis04Noch keine Bewertungen

- EAC Software SetupDokument19 SeitenEAC Software SetupBinh Minh NguyenNoch keine Bewertungen

- StatementDokument3 SeitenStatementSachinBMetre87 SachinBMetreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brahmss Pianos and The Performance of His Late Works PDFDokument16 SeitenBrahmss Pianos and The Performance of His Late Works PDFllukaspNoch keine Bewertungen

- Colleg Fee StructureDokument1 SeiteColleg Fee StructureSriram SaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- David T History Rev 26032019Dokument18 SeitenDavid T History Rev 26032019David TaleroNoch keine Bewertungen

- 720U2301 Rev 07 - Minimate Pro Operator ManualDokument126 Seiten720U2301 Rev 07 - Minimate Pro Operator ManualCristobalKlingerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Advanced Microscopy Simplifi Ed: Bx53M/BxfmDokument28 SeitenAdvanced Microscopy Simplifi Ed: Bx53M/BxfmRepresentaciones y Distribuciones FALNoch keine Bewertungen

- University of Colombo Faculty of Graduate Studies: PGDBM 504 - Strategic ManagementDokument15 SeitenUniversity of Colombo Faculty of Graduate Studies: PGDBM 504 - Strategic ManagementPrasanga WdzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marrantz Service Manual Using CS493263 09122113454050Dokument63 SeitenMarrantz Service Manual Using CS493263 09122113454050Lars AnderssonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fax 283Dokument3 SeitenFax 283gary476Noch keine Bewertungen

- Applsci 12 02711 v2Dokument31 SeitenApplsci 12 02711 v2Chandra MouliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Solid Desiccant DehydrationDokument5 SeitenSolid Desiccant Dehydrationca_minoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Broadcast Tools Site Sentinel 4 Install Op Manual v2 12-01-2009Dokument41 SeitenBroadcast Tools Site Sentinel 4 Install Op Manual v2 12-01-2009testeemailNoch keine Bewertungen

- Global Sources - 2010 June - Home ProductsDokument212 SeitenGlobal Sources - 2010 June - Home Productsdr_twiggyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Compact FlashDokument9 SeitenCompact Flashenpr87reddyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literature Study Nift ChennaiDokument5 SeitenLiterature Study Nift ChennaiAnkur SrivastavaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Content Marketing Solution StudyDokument39 SeitenContent Marketing Solution StudyDemand Metric100% (2)

- Naging: Case SelectingDokument5 SeitenNaging: Case SelectingPrabhakar RaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Item 3 Ips C441u c441r Ieb Main ListDokument488 SeitenItem 3 Ips C441u c441r Ieb Main Listcristian De la OssaNoch keine Bewertungen

- I R Lib ReferenceDokument117 SeitenI R Lib Referencebiltou0% (1)

- EN - 61558 - 2 - 4 (Standards)Dokument12 SeitenEN - 61558 - 2 - 4 (Standards)RAM PRAKASHNoch keine Bewertungen

- Delta Tester 9424 Training ModuleDokument35 SeitenDelta Tester 9424 Training ModuleNini FarribasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Karcher Quotation List - 2023Dokument12 SeitenKarcher Quotation List - 2023veereshmyb28Noch keine Bewertungen

- Using Gelatin For Moulds and ProstheticsDokument16 SeitenUsing Gelatin For Moulds and Prostheticsrwong1231100% (1)

- Statement of Purpose China PDFDokument2 SeitenStatement of Purpose China PDFShannon RutanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Usability Engineering (Human Computer Intreraction)Dokument31 SeitenUsability Engineering (Human Computer Intreraction)Muhammad Usama NadeemNoch keine Bewertungen