Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

POL 661: Environmental Law: NEPA - Overview

Hochgeladen von

Chad J. McGuireOriginaltitel

Copyright

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenPOL 661: Environmental Law: NEPA - Overview

Hochgeladen von

Chad J. McGuireDEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC POLICY

POL 661: Environmental Law

Lecture 4: NEPA - Overview Introduction

We begin our exploration of specific federal environmental laws with a statute that was passed as a comprehensive planning requirement that gets incorporated into most federal actions that have the potential to impact the environment. The concept we need to understand here is that federal laws to protect the environment can be more than regulatory in nature; federal laws can also have planning goals that help to ensure policy directives are met. As such, we can begin by looking at a programmatic statute that is very much like an overarching policy directive; rather than regulating a particular medium of the environment (like the air or water), this statute looks at any government activity that has the potential to impact the background state of the environment (its current condition) and seeks to address this impact by asking fundamental questions about alternative ways of accomplishing the action that creates less of an impact on those environmental assets.1 The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) is a federal statute passed by Congress with a stated goal of ensuring the environment is considered prior to any major federal actions. The role NEPA plays in federal law is one of scoping and planning; it forces government to do the following:

Note the idea of looking at the impacts of a proposed activity (like building a highway) on the existing environment is some acknowledgment of the ecologist perspective discussed earlier in the materials. Inherent in the idea of looking at potential impacts on current background states of the environment suggests those background states are important, just like the natural system theory proposes. We should consider this major assumption behind NEPA as a planning statute as we will certainly see some of the counter arguments of NEPA based on its additional costs when viewing the requirements in the context of the particular project under review (costs in terms of delay of the project, assessment costs, alternatives analysis, etc.). These cost arguments are similar to the economist viewpoint and may highlight a preference of immediate human wellbeing over the aggregation of environmental harms that might accrue to future generations.

Page 2 of 12 Think about the potential environmental impacts of a proposed project before engaging in the project;2 Identify and assess the environmental impacts where such impacts are likely; and Minimize those impacts to the extent practicable by identifying alternative strategies for the government action.

NEPA does not prevent government from acting in a certain way, but it makes sure that government considers environmental consequences of its actions. Imagine if we all had an environmental voice in our own heads that always made us think about the environmental impacts of our actions before taking action; NEPA is like this little voice, requiring government to consider the impacts of its actions on the environment. NEPA is often criticized as being wasteful and time consuming, preventing important economic activity from occurring and unnecessarily adding to the costs (time and money) of projects.3 On the other hand, NEPA is also lauded as being a steward of environmental awareness, providing sound policy options for government actions that have a likelihood of impacting environmental values.4

NEPA Overview

The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) was passed at the beginning of the environmental movement in the 1970s. It was actually signed into law by President Richard Nixon. What is most important about NEPA, from an environmental context, is its scope; NEPA applies to any Major Federal Action, Significantly Affecting the Human Environment. We will discuss exactly what this means in detail, but I want you to consider this potential scope of federal government activities. Imagine, for example, the Clean Air Act applies to one environmental medium, air. The Clean Water Act?

2

Consider the fact that NEPA requires an assessment of potential environmental impacts before any activity has occurred. This kind of proactive consideration of environmental harm is fundamentally different from the reactive nature of many environmental laws. Recall the earlier lectures where environmental laws were said to be mostly reactive (and thus remedial) in nature. The Clean Water Act was used as an example, where years of degrading water quality resulted in Congress finally taking action to remediate and ensure the quality of the nations waters. NEPA is different as an environmental statute because it asks government to think about environmental consequences prior to taking action. Of course proactively considering environmental harm is a bit difficult in implementation because it is hard to identify all of the potential impacts of an activity before it has occurred. Still, by conducting an environmental assessment (engaging in scientific observations) prior to taking action, a lot of the potential impacts on existing environmental conditions may be determined.

3 4

The economist argument. The ecologist argument.

Page 3 of 12 water. The Endangered Species Act? Certain species that have been determined to be threatened or endangered to the point of extinction. While these three laws are important in protecting the environment, they only deal with one specific medium at a time. NEPA, conversely, deals with ANY activity (with certain conditions) that has the potential to impact the environment. So, you should understand NEPA is important for no other reason than it covers a wide scope of conduct that may harm the environment.

Purposes of NEPA

NEPA has a dual purpose that can be divided into an external function and an internal function as follows: External Function: Inform the public about the potential environmental impacts of a proposed government action. Through NEPA, including the public disclosure requirements of the conducted environmental assessments, the public is made aware of the potential impacts of a proposed project prior to the project actually taking place. This allows the public to be educated and understand the potential impacts; it also allows the public (through administrative public hearing requirements) to voice their concerns about the proposed environmental impacts and provide comments about preferences (agreement or disagreement about the project in light of environmental impacts).5 Internal Function: Improve decision-making. Beyond informing the public about the environmental impacts of certain government actions, NEPA also seeks to improve the decision-making function of government when it chooses to engage in actions. The specific improvements sought center around the impact of government decisions on environmental assets. By engaging in the process of environmental review, government is afforded the ability to better understand the potential consequences of its actions on environmental resources. Through this internal education, government learns not only of the potential environmental impacts, but is also able to think about alternatives: ways of changing their proposed activity to mitigate (and even prevent) the environmental harm. Sometimes these changes can be done with slight modifications to the proposed

Consider that without NEPA many of the potential environmental impacts of a government project might go unnoticed. Even when noticed, the impacts might go unreported to the public. Thus, NEPA allows for a transparency between government actions and environmental impacts; the public is made aware of the potential impacts, and through this awareness there is a feedback opportunity where citizens can voice their concerns over the environmental impacts. If we are wearing our policy hats and thinking about the importance of transparency and public opinion in democratic systems, we may see the value of NEPA as a source of information to the public about environmental impacts of government actions. The extent to which we might agree with such outcomes is also dependent on how we feel about the costs incurred in such a process, particularly whether such costs aid or detract from efficiency in government actions (our economist/ecologist argument brought forward).

Page 4 of 12 project (for example changing the site of the project to protect critical habitat). Other times the modifications must be substantial, sometimes so substantial that the proposed activity is not longer seen as a viable option and the project is abandoned.6

Timing of NEPA

Section 102(2)(c) of NEPA indicates a federal agency must do an environmental analysis when there is a recommendation or report on a proposal for action. This is an interesting, and somewhat ambiguous, part of the statute as it concerns the timing of a NEPA review. Consider this in context: when precisely would you identify a NEPA review is required under this terminology? Practically, when would you want to do a NEPA review? Would you want to engage in all the preparation of a potential project, say choosing the location and engineering requirements of a proposed dam? Would you do all of the preliminary work first and then engage in the environmental assessment under NEPA? The statutory requirement seems to indicate NEPA can be done after a recommendation or report on a proposed action is issued, meaning after one has determined the location and logistics of the dam in our example here. But does this make practical sense? Would you want to engage in all of this work up front only to learn later that an endangered species lives on the proposed site of the construction? Some would argue the environmental assessment should be done either before or simultaneously with the review of the proposed activity; that way resources are expended as efficiently as possible, and expectations are tempered by the inclusion of the environmental assessment along with the analysis of suitability for the project outside of environmental considerations. However, it is certain that NEPA analysis must occur, and a failure to provide such an analysis before beginning construction on a project would violate the explicit requirements of the statute. A visual representation of timing considerations for NEPA is presented below as a means of conceptualizing the way in which NEPA requirements can be internalized into the decision-making process when government is proposing an activity that may impact the environment:

Again, there is no requirement in NEPA that a proposed project be abandoned; the statute itself does not require government to abandon a project. However, through the process of review and public disclosure, there may be practical reasons for government to choose to abandon a proposed project based on the extent of environmental impacts identified in the assessment process as well as the public response to the environmental impacts identified. For example, the administrative public notice and comment process can result in public outrage towards a proposed project. Such outrage may make the potential project politically infeasible, not because NEPA requires the project to be abandoned, but because the process of fact finding (environmental review) and transparency (publication of findings) has show the project to be unsupported by public opinion.

Page 5 of 12

To What Does NEPA Apply? Major

As stated in the book, NEPA only applies to major actions. So, of course, we need to determine what is major within the context of NEPA. What you should learn from the text is major is context dependant. This means one has to look at a project, in context, to determine if it is major enough for NEPA review. A good example to clarify the context issue is to consider a 30-story building. It certainly seems major, but let us consider a context to be sure. Consider this building is being erected in a small town. Since it would be the first 30-story building in the town, it would most likely be considered a major action simply because it is major in comparison to all of the other buildings in the community; in context of all other buildings in the town, a 30-story building is major. Take the same building, and place it in Manhattan. Because so many buildings in Manhattan are at least 30 stories, it is unlikely a major action for Manhattan purposes because, in the context of Manhattan, a 30-story building is relatively commonplace amongst the other structures in the city. Thus, we see the context analysis when determining major under NEPA. It is important to understand the contextual nature of NEPA because this means there is no absolute definition of what NEPA might apply to. Rather, NEPA is contextdependent, so an analysis of whether NEPA requires an environmental assessment prior to moving forward with a government project will always depend on the context of the situation. Even a small planned government project cannot be categorically exempted from NEPA review just because it is small in scale. Rather, the project must be looked at

Page 6 of 12 in the context of the area in which it will take place; if the area has sensitive environmental assets (say critical habitat for a listed endangered species), then there is a greater likelihood the context of the small project (the sensitive habitat upon which it will be built) may trigger an environmental review where the same project would not trigger such a review under a different context (an area where no endangered species habitat existed as an example).

Federal

The term federal in NEPA seems to significantly limit its application; if it only applies to federal actions, then it really does not have a wide application, right? Not really. When we start to consider all of the activities that involve federal action, we can see NEPA carries a wide scope. Consider, have you every taken out a student loan? Have you ever purchased a car with a loan? Have you ever financed a home? Do you have a bank account? All of these activities require some form of federal action. For the student loans, the federal action is through insurance guarantees. For the home and auto loans, there are federal laws controlling the loan process. For the bank account, the federal government insures the account (FDIC insurance). Now that you have some idea of how expansive a federal action can be, consider what types of federal acts might have impacts on the environment. I personally think of any form of development first. Developers require financing and insurance. Almost all significant financing projects have a federal component. Also, there are other environmental laws that require permitting through the development process; most of these permits are granted by the federal government or require some form of federal approval along the process. This is the same for oil and gas leases in the public lands of the United States, both of which require federal permits. The Big Dig a major project to improve traffic congestion in and around Boston, MA was financed in large part by federal money; it also required federal permitting. Most highways (state and federal of course) receive financing and permitting from the federal government. As shown in more detail in the text, the term federal applies to more actions than we initially think. Even when a project might not be considered federal but is still connected to public activities, NEPA-like processes may still apply. Most states have a state statutory equivalent to NEPA that requires all major state actions that may significantly effect the environment engage in an analysis of environmental impacts and assess alternatives.7 While we dont focus on the state equivalents in this course, you should be aware that a failure to meet the federal requirement as identified above does not mean the assessment of environmental impacts ends. From a policy standpoint, environmental impacts are generally considered if there is a government action, whether that action is federal or state in nature.

For example: Massachusetts (MEPA): http://www.mass.gov/eea/agencies/mepa/ California (CEQA): http://ceres.ca.gov/ceqa/

Page 7 of 12 One item to mention here that does affect a determination of federal action is the term action identified in NEPA. When there is an obvious federal actor, the only other question is to consider the kind of action taking place. If the action is discretionary in nature, meaning the federal agency has discretion on whether or not to act, then there is almost universal agreement discretionary federal acts constitute federal action for NEPA purposes. However, where the action is nondiscretionary, meaning the environmental impacts of a project are based on actions that a federal agency is commanded to take (for example by congressional mandate under a statute), there generally is no NEPA requirement triggered because there is no discretion on behalf of the agency in whether or not to engage in the action. Thus, we can say that NEPA only applies to discretionary federal acts; NEPA does not apply to nondiscretionary federal actions.8

Significant

Whether a proposed action is significant under NEPA is closely related to the major analysis described above. What this means is the idea of significance, like the idea of a project being major, is context dependent. Sometimes a project is limited in scope, and in isolation, does not appear to be significant. An example might be the permitting and building of a small section of a highway; the section itself might be relatively small in scale and it might be placed in an area where there is little environmental concern. However, if the entire project is considered (a section of highway does not have a purpose onto itself it only makes sense as part of the entire highway contemplated), then the project may be deemed significant in this wider context; for example, the project might show future segments of the highway traverses endangered species habitat. This is the issue of segmentation, and it highlights the importance of thinking about significance in context to the project itself, just like whether a government action is deemed major under NEPA is also considered in context.9

Environment

For certain, the term environment under NEPA includes any physical aspect of what we might consider the environment (land, water, air). However, it also includes non8

In addition, NEPA does not apply to direct presidential action (when the President of the United States takes direct action). NEPA only applies to federal agency action (executive branch actions excluding direct presidential action).

9

Note that this argument is very similar to the difference between economists and ecologists viewpoints about the environment. The idea of segmentation poses the question of how we look at proposed government projects for the purposes of determining environmental impacts. Do we focus solely on the immediate project under consideration (the economist viewpoint), or do we take a longer view of the issue and think about the fuller impact of the project over time (the ecologist viewpoint)? In answering this question we likely need to consider the policy behind NEPA as a statute and think about the goal(s) it is trying to achieve in relation to environmental protection.

Page 8 of 12 physical aspects of the environment. This can include cultural, historical, and aesthetic values. An example may be a proposed development on a Native American burial site; while the development may have minimal impacts to the surrounding physical environment, it may significantly impact the cultural and historical value of the burial ground. The same argument can be used for archeological sites. So, NEPA takes a generally expansive view of what is considered environment, going beyond what we may initially think.

The NEPA Process

Now that we have the main elements of NEPA, let us look at the actual process of NEPA (how it is actually implemented). Consider the following questionnaire showing the general NEPA process: Is there a major federal action that may significantly affect the environment? Yes: Then do an Environmental Assessment (EA). No: Then there is a Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI), and the project can move forward without further environmental review.

EA: Does the EA show a federal action that will likely have a significant impact on the environment? Yes: Then must do a full Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). No: Then there is a Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI), and the project can move forward without further environmental review.

EIS: Does the EIS show the federal action will significantly impact the environment? Yes: Then must consider alternatives to the project, including the no-action alternative. No: Then there is a Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI), and the project can move forward without further environmental review.

A visual representation of this decision tree questionnaire of the NEPA process is presented here:

Page 9 of 12

This questionnaire shows the general NEPA process. If there is the possibility of a project significantly affecting the environment, then the agency must do an Environmental Assessment (EA). This is a basic procedure, where the potential affects of the project on all environmental resources are reviewed. If the EA reveals a strong likelihood of environmental harm, the agency must engage in an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIS). This is a more formal procedure than the EA, where the agency does a detailed environmental analysis, discussing how each environmental factor will be affected, and stating the alternative actions to the proposed activity. If no environmental harm is shown at either the EA or EIS stage, then the agency indicates a Finding Of No Significant Impact (FONSI). The FONSI informs everyone that the project will not significantly affect environmental values at the proposed site. Now that we have discussed the general procedure required in a NEPA review, let us discuss the effect of NEPA, i.e., does it really do anything?

The Effect of NEPA

One thing should become apparent under a close examination of NEPA; if you look at the flow chart above, you realize NEPA requires agencies of the federal government to engage in a review process of actions that may affect the environment. Many wonder if this actually changes projects, or stops them from going forward. In other words, is there a part of NEPA that requires a project to be stopped when there is a finding of major impacts to the environment? The answer is a surprising NO. NEPA is mostly a

Page 10 of 12 procedural statute; this means it requires a procedure to be followed, but does not require a specific result. Thus, where a project is shown to cause significant environmental harm, there is no requirement under NEPA the applicant change the project (or stop it altogether). There may be other statutes that require the applicant change their project (or stop it), but NEPA does not require such a result. The goal or effect of NEPA is to ensure the environmental effects of a proposed project are fully considered prior to moving forward with the project. This full consideration is done through the environmental harm analysis, and the requirement under NEPA that all alternatives to the proposed project are considered, including the no action alternative. Although NEPA is not intended to prevent federal actions from moving forward, this often results when the process shows there will likely be significant impacts on environmental assets. During the information gathering stage, government entities are able to better assess the potential impacts of their proposals on environmental assets (the internal function of NEPA); often this internal deliberation results in a decision to alter the project to protect sensitive environmental assets, and when this cannot be done, a decision to drop the plan altogether may result. In addition, the external function of informing the public about potential environmental harms may result in a public backlash towards the project. Since government is receptive of public sentiment in a democratic system, there is a likelihood that a strong enough outrage over the proposed project can also result in an abandonment of the project. Finally, there are also judicial impediments to projects moving forward when NEPA requirements are not closely followed. When government has failed to do the environmental analysis under NEPA, or the analysis has been completed but a group is able to show the government has failed to meaningfully consider the alternatives, including the no action alternative, then a judge may order a project halted (and even removed if already built) in order to comply with the NEPA review process. Many environmental groups enforce this procedural requirement of NEPA by suing the federal government when they believe it has failed to consider the alternatives to a proposed project. The additional costs and burdens placed on government to comply with NEPAs requirements can act as a disincentive to move forward with the project under the conditions presented.

Cape Wind

Cape Wind represents a recent example of how the NEPA process is employed (for good or bad) to determine the environmental effects of a proposed project. The actual EIS can be viewed with a quick net search.10 Let us run through the NEPA analysis above (for ourselves) as it relates to Cape Wind. First, is Cape Wind a major action? Well, it stands as the first major federal offshore wind project in the United States. The fact it would be the first such project would likely

10

One link is here (note the section on NEPA Documentation: http://www.boem.gov/Renewable-Energy-Program/Studies/Cape-Wind.aspx

Page 11 of 12 propel it into the major category because of its context. Is the action federal? This is easy, as the facility is an energy generation facility, so it requires federal permitting. Also, it will be placed in federal waters (not privately owned and outside of state jurisdiction), so it needs a permit for its location (actually a lease for the space). Thus, there must be federal action. Is the project significant? Going back to what I have said above, if it is major, it generally is also significant. However, consider the uniqueness of the project, and the fact of where it will be placed; it is arguable the project can be determined significant simply based on its unique nature (at least for the United States). Beyond its first of a kind status, the project is also substantial in scale (you can review the link provided in the footnote for precise details it keeps changing) and is likely therefore significant for this reason as well. Will the project harm the environment? This is where the analysis gets interesting. If you look at the EIS, you will find there are limited affects on the physical environment. This is so much the case that it is hard to see the significant impact on physical environment alone. However, as stated above, environment includes historical, cultural, and aesthetic values as well. Can anyone guess what aesthetic value (and cultural to a degree) has been the main sticking point for the project? If anyone guessed the view from the Kennedy compound (as well as other Cape areas), you guessed right! In fact, you can find the aesthetic impacts on the EIS website for Cape Wind. And recently, additional cultural considerations have been identified including a claim the project creates a visual disruption for certain groups of Native Americans who have traditionally used the unobstructed of Nantucket Sound as a place of ceremonial significance. So, Cape Wind is really a good example of how an extended definition of environment has frustrated the Cape Wind project. At the same time, it helps to explain how powerful NEPA is in the overall environmental assessment of projects in the United States. Indeed, NEPA can be used as both a shield for the environment as well as a sword for those who are interested in using legal instruments as a means of advancing personal agendas.11

Conclusion

In this section you should have a good understanding of the purpose of NEPA (what it is meant to do) as well as a solid foundation of the process and effect of NEPA. As stated, NEPA has an intended goal of ensuring the environment is considered as part of government activities, particularly government activities that have the potential to significantly impact environmental assets. One cannot help but note how this desire to protect environmental assets (as they exist today) is some recognition of the importance of background environmental conditions. Such recognition gives support to the ecological viewpoint that focuses on interactions of the natural system and places the

11

It should be understood that the law is often utilized strategically to advance personal agendas, even when those agendas are not part of the policy goals defined within the law itself. For a more detailed exploration of how this might work in practice (within the context of fishery management), please see here: http://works.bepress.com/chad_mcguire/14/

Page 12 of 12 environment as the outer limit upon which human society and economic activity is constrained. Recall the figure used to make this point earlier in the course (copied below here):

If this assumption of the relationship between environment, society, and economic activity is found in federal environmental statutes like NEPA, then we should consider its importance in how we perceive environmental laws generally. We will find some variation from this theme in other areas of environmental protection later in the course. For now, we can see that this goal of NEPA can have a profound effect on the immediate economic interests of society; NEPA can retard economic prosperity by slowing, and sometimes preventing, federal activities from moving forward. Whether we see this as an important check on our actions, or as an unnecessary limitation harming human wellbeing is an important part of the policy debate that surrounds environmental laws generally, and NEPA particularly. Once again how we ultimately decide the value of NEPA is highly dependent on whether we subscribe more towards the ecological or economist ends of the spectrum. END OF SECTION.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Honda Fit Timing ChainDokument14 SeitenHonda Fit Timing ChainJorge Rodríguez75% (4)

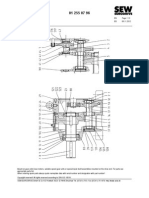

- Parts List 01 255 07 96: Helical Gear Unit R107Dokument3 SeitenParts List 01 255 07 96: Helical Gear Unit R107Parmasamy Subramani50% (2)

- Flight Training Instruction: Naval Air Training CommandDokument174 SeitenFlight Training Instruction: Naval Air Training CommandITLHAPN100% (1)

- Clan Survey Pa 297Dokument16 SeitenClan Survey Pa 297Sahara Yusoph SanggacalaNoch keine Bewertungen

- POL 661: Environmental Law: NEPA - RemediesDokument7 SeitenPOL 661: Environmental Law: NEPA - RemediesChad J. McGuireNoch keine Bewertungen

- Historical OriginsDokument4 SeitenHistorical OriginsYnah Llanessa BermasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Environmental ManagementDokument32 SeitenEnvironmental ManagementEmsNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Philippine Environmental Impact Statement SystemDokument31 SeitenThe Philippine Environmental Impact Statement SystemJasper LinsanganNoch keine Bewertungen

- EIA General ReadingDokument19 SeitenEIA General ReadingmarkNoch keine Bewertungen

- History of EiaDokument4 SeitenHistory of EiaMoHaMaD SaIFuLNiZaM BiN HaMDaN100% (2)

- EpaDokument22 SeitenEpashubham aroraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA)Dokument15 SeitenEnvironmental Impact Assessment (EIA)Alina niazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Precautionary PrincipleDokument8 SeitenPrecautionary PrincipleAngel GonzalezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 5 Environmental AssessmentDokument29 SeitenUnit 5 Environmental AssessmentAmitNoch keine Bewertungen

- POL 661: Environmental Law: Pollution: Overview and Private ControlsDokument14 SeitenPOL 661: Environmental Law: Pollution: Overview and Private ControlsChad J. McGuireNoch keine Bewertungen

- EIA - Wikipedia PDFDokument1 SeiteEIA - Wikipedia PDFakshay thakurNoch keine Bewertungen

- WP 66Dokument48 SeitenWP 66show docNoch keine Bewertungen

- 07 Chapter2Dokument25 Seiten07 Chapter2sihaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Environmental Impact AssessmentDokument12 SeitenEnvironmental Impact AssessmentSekelani LunguNoch keine Bewertungen

- Environmental Impact Assessment: NEPA: The National Environmental Policy ActDokument10 SeitenEnvironmental Impact Assessment: NEPA: The National Environmental Policy ActsruisruiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Environmental Awareness 1.0Dokument39 SeitenEnvironmental Awareness 1.0Maria Del Cielo PahinagNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ajph 61 7 1425Dokument4 SeitenAjph 61 7 1425nghiasipraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Env LawDokument29 SeitenEnv Law01fe19bcs265Noch keine Bewertungen

- Environmental Impact Assessment: Ramitha.GDokument51 SeitenEnvironmental Impact Assessment: Ramitha.GCF forumNoch keine Bewertungen

- IEMA Certificate - Day 3Dokument41 SeitenIEMA Certificate - Day 3OsamaAlaasamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Environmental PolicyDokument46 SeitenEnvironmental PolicyJennifer Ze100% (1)

- An EIGHT Step Environmental Analysis Process and Its Associated OutputsDokument3 SeitenAn EIGHT Step Environmental Analysis Process and Its Associated OutputsShilpi JauhariNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Challenges of The Environmental Impact Assessment Practice in NigeriaDokument9 SeitenThe Challenges of The Environmental Impact Assessment Practice in Nigeriaijsret100% (9)

- 1987 UNEP Goals and Principles of Environmental Impact AssessmentDokument2 Seiten1987 UNEP Goals and Principles of Environmental Impact AssessmentjouchanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effects Nanotech FinalDokument34 SeitenEffects Nanotech FinalBerliantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Enviromental Law AssignmentDokument11 SeitenEnviromental Law AssignmentDamilola RhodaNoch keine Bewertungen

- EIA MethodsDokument35 SeitenEIA MethodsBudi NadatamaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Odyssey of Constitutional PolicyDokument6 SeitenThe Odyssey of Constitutional Policyellen joy chanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Environmental Impact Assessment Challenges and OpportunitiesDokument29 SeitenEnvironmental Impact Assessment Challenges and OpportunitiesdavidNoch keine Bewertungen

- POL661: Lecture 1Dokument10 SeitenPOL661: Lecture 1Chad J. McGuireNoch keine Bewertungen

- How The Environmental Impact Assessment Is Different in Various Countries and Drawing From Its Comparison, How Our Laws Can Be Improved?Dokument5 SeitenHow The Environmental Impact Assessment Is Different in Various Countries and Drawing From Its Comparison, How Our Laws Can Be Improved?Donka RaviNoch keine Bewertungen

- NEPADokument21 SeitenNEPARiddhi DhumalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eia PDFDokument51 SeitenEia PDFAJAY MALIKNoch keine Bewertungen

- Environmental Impact AssessmentDokument17 SeitenEnvironmental Impact AssessmentnebyasNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is Environmental LawDokument8 SeitenWhat Is Environmental Lawsuvarna nilakhNoch keine Bewertungen

- General Assessment PrincipleDokument7 SeitenGeneral Assessment PrincipleLEHLABILE OPHILIA TSHOGANoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) SystemDokument4 SeitenPhilippine Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) SystemHarvey GuemoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Environmental Resource5 Environmental Impact AssesmentsDokument6 SeitenEnvironmental Resource5 Environmental Impact Assesmentsamit545Noch keine Bewertungen

- POL 661: Environmental Law: Do We Need Environmental Law? Where Do Environmental Laws Come From?Dokument9 SeitenPOL 661: Environmental Law: Do We Need Environmental Law? Where Do Environmental Laws Come From?Chad J. McGuireNoch keine Bewertungen

- Environmental Impact AssessmentDokument2 SeitenEnvironmental Impact AssessmentMichael SmithNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2.eia StepsDokument45 Seiten2.eia StepspushprajNoch keine Bewertungen

- National Environmental Protection Act AND The Philippine Environmental Impact Statement SystemDokument14 SeitenNational Environmental Protection Act AND The Philippine Environmental Impact Statement SystemHariette Kim TiongsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- 04 Calvert Ciffs Coordinating Committee v. US Atomic Energy CommissionDokument33 Seiten04 Calvert Ciffs Coordinating Committee v. US Atomic Energy CommissionTet VergaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cahpet VIDokument43 SeitenCahpet VIAytenew AbebeNoch keine Bewertungen

- VASQUEZ, GILBERT 2020-0002 (Philippine Environment Impact Statement System)Dokument1 SeiteVASQUEZ, GILBERT 2020-0002 (Philippine Environment Impact Statement System)Gilbert VasquezNoch keine Bewertungen

- ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT FinalDokument15 SeitenENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT Finalnp27031990100% (1)

- Environmental Impact Assessment Process in IndiaDokument7 SeitenEnvironmental Impact Assessment Process in IndiaGangalakshmi PrabhakaranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Environmental Impact Assessment: A Critique On Indian Law and PracticesDokument5 SeitenEnvironmental Impact Assessment: A Critique On Indian Law and PracticesSneh Pratap Singh ChauhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Environmental Impact Assessment - WikipediaDokument20 SeitenEnvironmental Impact Assessment - WikipediagayathriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Subject: Environmental Impact Assessment (Eia) Assignment No. 2Dokument3 SeitenSubject: Environmental Impact Assessment (Eia) Assignment No. 2RiddhiNoch keine Bewertungen

- BSECE 4A Environmental Laws ReportDokument9 SeitenBSECE 4A Environmental Laws ReportCatherine BalanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impact Significance Determination - Basic Considerations and A Sequenced ApproachDokument23 SeitenImpact Significance Determination - Basic Considerations and A Sequenced ApproachjoytoriolsantiagoNoch keine Bewertungen

- f979cdd7b57334a2d33ed509650371fcDokument70 Seitenf979cdd7b57334a2d33ed509650371fcreasonorgNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is An Impact?: The Impact of An Activity Is A Deviation (A Change) From The That Is Caused by The ActivityDokument27 SeitenWhat Is An Impact?: The Impact of An Activity Is A Deviation (A Change) From The That Is Caused by The ActivityarifNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ceam Principles, Processes, and Practices: Environmental Impact Assessment PP-1Dokument10 SeitenCeam Principles, Processes, and Practices: Environmental Impact Assessment PP-1Anonymous Z2pby9SqlHNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Handbook for Integrity in the Environmental Protection AgencyVon EverandThe Handbook for Integrity in the Environmental Protection AgencyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Environmental LawDokument33 SeitenEnvironmental Lawbhargavi mishra100% (1)

- Environmental Justice PolicyDokument27 SeitenEnvironmental Justice PolicyTravis KellarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Environmental Policy Under Reagan's Executive Order: The Role of Benefit-Cost AnalysisVon EverandEnvironmental Policy Under Reagan's Executive Order: The Role of Benefit-Cost AnalysisNoch keine Bewertungen

- POL663: Lecture 2Dokument10 SeitenPOL663: Lecture 2Chad J. McGuireNoch keine Bewertungen

- POL663 Lecture 6Dokument11 SeitenPOL663 Lecture 6Chad J. McGuireNoch keine Bewertungen

- SUS101: Principles of Sustainability - SyllabusDokument6 SeitenSUS101: Principles of Sustainability - SyllabusChad J. McGuireNoch keine Bewertungen

- POL663 Lecture 1Dokument11 SeitenPOL663 Lecture 1Chad J. McGuireNoch keine Bewertungen

- POL 663: Ocean Policy and Law: The Coast Public Access To Beaches and ShoresDokument11 SeitenPOL 663: Ocean Policy and Law: The Coast Public Access To Beaches and ShoresChad J. McGuireNoch keine Bewertungen

- POL661: Environmental Law Course SyllabusDokument4 SeitenPOL661: Environmental Law Course SyllabusChad J. McGuireNoch keine Bewertungen

- POL 663: Ocean Policy and Law: Management of Coastal Resources The Coastal Zone Management Act (CZMA)Dokument9 SeitenPOL 663: Ocean Policy and Law: Management of Coastal Resources The Coastal Zone Management Act (CZMA)Chad J. McGuireNoch keine Bewertungen

- POL 661: Environmental Law: WasteDokument9 SeitenPOL 661: Environmental Law: WasteChad J. McGuireNoch keine Bewertungen

- POL 661: Environmental LawDokument9 SeitenPOL 661: Environmental LawChad J. McGuireNoch keine Bewertungen

- POL 663: Ocean Policy and Law: Offshore Resource Development Property Rights in The OceanDokument14 SeitenPOL 663: Ocean Policy and Law: Offshore Resource Development Property Rights in The OceanChad J. McGuireNoch keine Bewertungen

- POL663: Ocean Policy & Law SyllabusDokument5 SeitenPOL663: Ocean Policy & Law SyllabusChad J. McGuireNoch keine Bewertungen

- POL 661: Environmental Law: EnergyDokument8 SeitenPOL 661: Environmental Law: EnergyChad J. McGuireNoch keine Bewertungen

- POL562: Environmental Policy SyllabusDokument7 SeitenPOL562: Environmental Policy SyllabusChad J. McGuireNoch keine Bewertungen

- POL 661: Environmental Law: Do We Need Environmental Law? Where Do Environmental Laws Come From?Dokument9 SeitenPOL 661: Environmental Law: Do We Need Environmental Law? Where Do Environmental Laws Come From?Chad J. McGuireNoch keine Bewertungen

- POL 661: Environmental Law: Land Use: Introduction and Private ControlsDokument12 SeitenPOL 661: Environmental Law: Land Use: Introduction and Private ControlsChad J. McGuireNoch keine Bewertungen

- POL 661: Environmental Law: Land Use: Public ControlsDokument8 SeitenPOL 661: Environmental Law: Land Use: Public ControlsChad J. McGuireNoch keine Bewertungen

- POL 661: Environmental Law: Pollution: Public ControlsDokument12 SeitenPOL 661: Environmental Law: Pollution: Public ControlsChad J. McGuireNoch keine Bewertungen

- POL 661: Environmental Law: Pollution: Overview and Private ControlsDokument14 SeitenPOL 661: Environmental Law: Pollution: Overview and Private ControlsChad J. McGuireNoch keine Bewertungen

- POL 661: Environmental Law: How To Find The Law?Dokument7 SeitenPOL 661: Environmental Law: How To Find The Law?Chad J. McGuireNoch keine Bewertungen

- POL661: Lecture 1Dokument10 SeitenPOL661: Lecture 1Chad J. McGuireNoch keine Bewertungen

- POL611: Administrative Law SyllabusDokument4 SeitenPOL611: Administrative Law SyllabusChad J. McGuire100% (1)

- POL611: Module 2B LectureDokument9 SeitenPOL611: Module 2B LectureChad J. McGuireNoch keine Bewertungen

- IX. Values - Subjective Emotion, Public Outrage, NIMBY: A. IntroductionDokument5 SeitenIX. Values - Subjective Emotion, Public Outrage, NIMBY: A. IntroductionChad J. McGuireNoch keine Bewertungen

- I. General Introduction To Administrative LawDokument5 SeitenI. General Introduction To Administrative LawChad J. McGuireNoch keine Bewertungen

- POL562: Module Three LectureDokument6 SeitenPOL562: Module Three LectureChad J. McGuireNoch keine Bewertungen

- POL562: Module Two LectureDokument5 SeitenPOL562: Module Two LectureChad J. McGuireNoch keine Bewertungen

- V. Economics - Categories Natural Resource, Ecological, Discounting, Substitution, TradeoffsDokument7 SeitenV. Economics - Categories Natural Resource, Ecological, Discounting, Substitution, TradeoffsChad J. McGuireNoch keine Bewertungen

- POL562: Module One LectureDokument6 SeitenPOL562: Module One LectureChad J. McGuireNoch keine Bewertungen

- VI. Economics - Defining Value Measuring Wellbeing, GDP, AlternativesDokument5 SeitenVI. Economics - Defining Value Measuring Wellbeing, GDP, AlternativesChad J. McGuireNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oracle9i Database Installation Guide Release 2 (9.2.0.1.0) For WindowsDokument274 SeitenOracle9i Database Installation Guide Release 2 (9.2.0.1.0) For WindowsrameshkadamNoch keine Bewertungen

- RX-78GP03S Gundam - Dendrobium Stamen - Gundam WikiDokument5 SeitenRX-78GP03S Gundam - Dendrobium Stamen - Gundam WikiMark AbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Value Creation Through Project Risk ManagementDokument19 SeitenValue Creation Through Project Risk ManagementMatt SlowikowskiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rajiv Verma CVDokument3 SeitenRajiv Verma CVrajivNoch keine Bewertungen

- SSMT Solution ManualDokument12 SeitenSSMT Solution ManualPraahas Amin0% (1)

- Unit 9 Computer NetworksDokument8 SeitenUnit 9 Computer NetworksDaniel BellNoch keine Bewertungen

- Swaroop (1) ResumeDokument4 SeitenSwaroop (1) ResumeKrishna SwarupNoch keine Bewertungen

- First Page PDFDokument1 SeiteFirst Page PDFNebojsa RedzicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brake Actuator Instruction - ManualDokument32 SeitenBrake Actuator Instruction - ManualJoeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cambridge Ordinary LevelDokument4 SeitenCambridge Ordinary LevelHaziq AfzalNoch keine Bewertungen

- LogDokument2 SeitenLogFerdian SumbaNoch keine Bewertungen

- BeartopusDokument6 SeitenBeartopusDarkon47Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ancient Civilizations AssignmentDokument3 SeitenAncient Civilizations Assignmentapi-240196832Noch keine Bewertungen

- Spot Cooling ResearchDokument7 SeitenSpot Cooling ResearchAkilaJosephNoch keine Bewertungen

- Retail Generation ZDokument24 SeitenRetail Generation ZSomanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Six Tsakalis Pedal ManualDokument1 SeiteSix Tsakalis Pedal ManualAdedejinfoNoch keine Bewertungen

- CEN ISO TR 17844 (2004) (E) CodifiedDokument7 SeitenCEN ISO TR 17844 (2004) (E) CodifiedOerroc Oohay0% (1)

- ASME B16.47 Series A FlangeDokument5 SeitenASME B16.47 Series A FlangePhạm Trung HiếuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 4 (Digital Modulation) - Review: Pulses - PAM, PWM, PPM Binary - Ask, FSK, PSK, BPSK, DBPSK, PCM, QamDokument7 SeitenChapter 4 (Digital Modulation) - Review: Pulses - PAM, PWM, PPM Binary - Ask, FSK, PSK, BPSK, DBPSK, PCM, QamMuhamad FuadNoch keine Bewertungen

- ToshibaDokument316 SeitenToshibaRitesh SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vacuum WordDokument31 SeitenVacuum Wordion cristian OnofreiNoch keine Bewertungen

- OC Thin Shell Panels SCREENDokument19 SeitenOC Thin Shell Panels SCREENKushaal VirdiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rajasthan BrochureDokument31 SeitenRajasthan BrochureMayank SainiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spherical Pillow Block Manual (MN3085, 2018)Dokument13 SeitenSpherical Pillow Block Manual (MN3085, 2018)Dillon BuyeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Advantages of Group Decision MakingDokument1 SeiteAdvantages of Group Decision MakingYasmeen ShamsiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3600 2 TX All Rounder Rotary Brochure India enDokument2 Seiten3600 2 TX All Rounder Rotary Brochure India ensaravananknpcNoch keine Bewertungen