Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Classroom Management

Hochgeladen von

Juravle PetrutaOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Classroom Management

Hochgeladen von

Juravle PetrutaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

This article was downloaded by: [Central U Library of Bucharest] On: 05 January 2013, At: 05:02 Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

NHSA Dialog: A Research-to-Practice Journal for the Early Childhood Field

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/hnhd20

Classroom Management Strategies for Young Children with Challenging Behavior Within Early Childhood Settings

Kristine Jolivette & Elizabeth A. Steed

a a a

Department of Educational Psychology and Special Education, Georgia State University Version of record first published: 20 Jul 2010.

To cite this article: Kristine Jolivette & Elizabeth A. Steed (2010): Classroom Management Strategies for Young Children with Challenging Behavior Within Early Childhood Settings, NHSA Dialog: A Research-to-Practice Journal for the Early Childhood Field, 13:3, 198-213 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15240754.2010.492358

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

NHSA Dialog, 13(3), 198213 Copyright C 2010, National Head Start Association ISSN: 1524-0754 print / 1930-9325 online DOI: 10.1080/15240754.2010.492358

DIALOG FROM THE FIELD

Downloaded by [Central U Library of Bucharest] at 05:02 05 January 2013

Classroom Management Strategies for Young Children with Challenging Behavior Within Early Childhood Settings

Kristine Jolivette and Elizabeth A. Steed

Georgia State University, Department of Educational Psychology and Special Education

Many preschool, Head Start, and kindergarten educators of young children express concern about the number of children who exhibit frequent challenging behaviors and report that managing these behaviors is difcult within these classrooms. This article describes research-based strategies with practical applications that can be used as part of classroom management practices in settings with young children to improve childrens social skills and decrease challenging behaviors. These strategies also are discussed in the context of program-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports. Finally, training opportunities and online resources are provided for teachers to continue their professional development regarding classroom management. Keywords: behavior problems, emotional development

The early years provide teachers with many opportunities to intervene with children who display challenging behaviors prior to misbehavior becoming the norm for the child and for future failures (Webster-Stratton, Reid, & Stoolmiller, 2008). However, many teachers report that young children are displaying challenging behaviors in their classrooms, which is of great concern for teachers and families (Alkon, Ramler, & MacLennan, 2003; Kupersmidt, Bryant, & Willoughby, 2000; West, Denton, & Reaney, 2001). For example, preschool teachers report that as many as 40% of their students engage in at least one challenging behavior every day (Willoughby, Kupersmidt, & Bryant, 2001). When a child or several children display challenging behaviors during the school day, the school day and experiences can be compromised negatively by (a) the teacher losing critical instructional time (Raver et al., 2008), (b) the teacher spending more time disciplining children than teaching them (Kern & State, 2009), (c) potential expulsion from the setting (Frey, Young, Gold, & Trevor, 2008; Park & Scott, 2009), (d) poor teacherstudent interactional patterns

Correspondence should be addressed to Kristine Jolivette, Georgia State University, Department of Educational Psychology and Special Education, Box 3979, Atlanta, GA 30302-3979. E-mail: kjolivette@gsu.edu

CLASSROOM MANAGEMENT

199

(Mantzicopoulos, 2005), (e) poor peer relations (Coie & Dodge, 1998), and (f) the development of patterns of misbehavior (Lipsey & Derzon, 1998). For these children, teachers need to use a variety of classroom management strategies to prevent future occurrences of challenging behavior and to promote childrens social development. The reasons some young children display challenging behavior and others do not are still being investigated. Some research indicates that when multiple risk factors (e.g., exposure to violence and abuse, poverty) are present, a child may be more likely to display challenging behaviors than others (Conroy & Brown, 2004; Qi & Kaiser, 2003). No matter the underlying risk factors present in a childs life outside of an early childhood setting, teachers still have the opportunity to teach, model, and reinforce expected, appropriate behaviors and put the young child on a path to success. To assist teachers with their classroom management practices, researchers have studied various approaches to professional development. For example, Raver et al. (2008) conducted a clustered randomized controlled study of 35 Head Start classrooms to assess the classroom emotional climates for teachers who received classroom management training with in-class coaching and observations with feedback from mental health professionals versus teachers who did not receive the intervention. They found that the environment and climate of the intervention classrooms were signicantly improved. Raver et al. (2008) hypothesized that the improvements were a byproduct of the intervention package and the on-site coaching and feedback provided a mechanism for teacher needs to be met without coercive childadult interactions occurring during difcult situations (e.g., a child engaging in aggressive behaviors or constant classroom disruption). They contended that it is imperative for teachers of young children to receive ongoing support to best meet the needs of their class. In another example, Webster-Stratton et al. (2008) used a randomized trial to investigate the effects of the Incredible Years Dinosaur curricula with an emphasis on classroom management for 34 classroom settings (Head Start and elementary) using direct observations, rating scales, and questionnaires on teacher and student behaviors. They found that teachers in the intervention group had moderate to high effect sizes in improvements to their classroom management and students in these classrooms showed increases in their appropriate school readiness and behavioral repertoires. Both of these studies suggest that when teachers of young children who display challenging behavior are given effective classroom management strategies and training, child behavior and classroom environment improves. For those not part of formal research studies with training and support, this article provides teachers of young children displaying challenging behavior multiple research-based classroom management strategies that can be used to address childrens challenging behavior. Effective practices are those that are systematically applied over the long term with emphasis on teaching and practicing the new behavior to maximize generalization (Peacock Hill Working Group, 1991). In addition, effective practices need to be matched to the childs problem and may include a multimethod approach that is continuously monitored (Peacock Hill Working Group, 1991). This article focuses on a few empirically supported strategies that can be used in settings with young children and after the strategy is summarized, an applicable case study or practical application of the strategy follows. These strategies were selected based on their ease of implementation, costeffectiveness, and exibility for use with individuals, small groups, and whole classes of children. Overall, the purpose of this article is to highlight a cadre of empirically supported strategies for teachers and programs to utilize as a means to support and foster the social growth of the young children in their Head Start programs, preschools, and kindergarten classrooms. These strategies

Downloaded by [Central U Library of Bucharest] at 05:02 05 January 2013

200

JOLIVETTE AND STEED

Downloaded by [Central U Library of Bucharest] at 05:02 05 January 2013

are presented as classroom management practices and then discussed in terms of scaling up these practices for possible adaptation for program-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports (PWPBIS). Several classroom management strategies that have a research base to support their use with individual children, small groups of children, or whole class applications are provided. As a whole, classroom management methods typically involve low-cost prevention and intervention strategies that may be used with large groups of children (Fox, Dunlap, Hemmeter, Joseph, & Strain, 2003). Many classroom management methods may be introduced in large group settings (e.g., circle time, outdoor time) and embedded into typical classroom activities, such as free choice time, transitions, and through stories and songs. For example, Serna, Nielsen, Lambros, and Forness (2000) taught the social skills of following directions, sharing, and problem solving through stories and songs for children who were at risk for emotional or behavioral disorders. Children who received the classroom management interventions through stories and songs demonstrated improved adaptive and social behavior compared with children who did not receive the intervention. Classroom management strategies may include (a) dening and teaching behavioral expectations, (b) using positive reinforcement to promote the engagement in prosocial skills (Stormont, Smith, & Lewis, 2007), (c) using group contingencies and token economies to encourage positive interactions between children with and without disabilities (e.g., Kohler, Strain, Hoyson, & Davis, 1995), (d) providing choices to promote independence and appropriate behavior (Jolivette, McCormick, Jung, & Lingo, 2004; Jolivette, McCormick, McLaren, & Steed, 2009; McCormick, Jolivette, & Ridgely, 2003), (e) using precorrection to set the stage for the expected behavior (Stormont et al., 2007), and (f) using functional communication training to promote improved child communication skills (Durand & Carr, 1991). The overall effects of implementing these classroom strategies on child behavior rely on the consistency of implementation over time and the use of a variety of strategies to create predictable classroom routines. These strategies are often infused into professional development models for early childhood educators (e.g., Hemmeter & Fox, 2009; McLaren, Hall, & Fox, 2009).

DEFINING AND TEACHING BEHAVIORAL EXPECTATIONS One of the rst classroom management practices a teacher may implement to prevent problem behavior is to dene the behaviors that all children in the classroom are expected to display. The use of classroom rules has been demonstrated in research to encourage childrens use of desired social behaviors and skills while reducing their challenging behavior (e.g., Benedict, Horner, & Squires, 2007). When developing classroom rules, teachers should begin by asking what specic childrens behavioral issues are most important to address in their class. Then, these behavioral issues need to be phrased into positive statements and then into easy-to-remember rules. Given the developmental abilities of young children, these rules should be few in number, have limited text, and be easily depicted by picture. In addition, family input could be obtained throughout this process through informal conversations or letters. For example, Ms. Schmidt identied four broad behavioral issues of most concern within her class: children (a) ghting over materials, (b) hitting each other and staff, (c) breaking or throwing classroom materials, and (d) running in the classroom. Ms. Schmidt rephrased these concerns into positive statements: children will share materials, children will take care of materials, children

CLASSROOM MANAGEMENT

201

Downloaded by [Central U Library of Bucharest] at 05:02 05 January 2013

will use safe hands and feet, and children will use walking feet indoors. Then she picked three of these statements and further simplied them into rules that would be easy for her class to remember: Be a Good Friend, Be Safe with Your Body, and Be Safe with Your Things. Ms. Schmidt and her assistant then made rule posters that included words of each rule with accompanying pictures of children engaging in the rules. These rule posters were hung on all four walls of the classroom and both sides of all doors within the classroom at childrens eye level. Due to the general nature of the classroom rules, they identied specic behavioral expectations for each rule that aligned with each classroom routine (e.g., arrival, snack, outside play; see Muscott, Pomerleau, & Szczesiul, 2009, for an example) as well as created explicit lesson plans to teach the rules during natural classroom routines. These lessons included (a) verbal explanation of the rules and what the words mean; (b) demonstration of the behaviors associated with the rules by teachers, children, and picture examples; and (c) question-and-answer sessions in which children identify examples and nonexamples of rule-following behaviors.

POSITIVE REINFORCEMENT In addition to dening and teaching behavioral expectations, classroom management strategies may include the use of positive reinforcement encouraging and following childrens use of desired social behaviors and skills within the classroom. Most people, including children, like to be recognized for a job well done. For young children who may not have long histories of academic and social success, this recognition can serve as a tool to promote social growth. Broadly, such recognition can be considered positive reinforcement. Positive reinforcement is the provision of a consequence (typically a positive, preferred reinforcer) contingent on an appropriate behavior (Lewis, Hudson, Richter, & Johnson, 2004). In other words, when a young child displays a positive behavior, no matter how small or even if it approximates a positive behavior, it provides the teacher with an opportunity to positively reinforce the child using one of several types of reinforcement. Four types of positive reinforcement are illustrated (see Table 1). Tania attends the Joshua Hill Head Start program and is in Ms. Schmidts class. Ms. Schmidt has noticed that she has difculties during free choice center time in the morning, especially in the block area when trying to initiate and maintain play interactions with her peers. She has observed Tania to verbally say, Play with me, and if a peer says no or ignores her, Tania pushes the peer and throws a block at the peer. She recognizes that Tania is not adhering to the classroom rules of Be a Good Friend and Be Safe with Your Things and that if these inappropriate behaviors continue, her peer relationships will erode further. In addition, Ms. Schmidt is worried that her interactions with Tania are becoming negative as she is constantly reprimanding her during this activity. For Tania, Ms. Schmidt will want to review the classroom rules and matrix and may want to use positive reinforcement to catch Tania being appropriate instead of waiting for the challenging behaviors to occur. For instance, she can provide Tania with verbal positive reinforcement when she is observed to engage in appropriate play and sharing skills. Ms. Schmidt may say, Tania, I like how you are letting Ben put blocks where he wants tothats a great way to Be Safe with Our Bodies and Things, or Tania, good job asking Liticia to play and then asking Ben when Liticia decided to draw by herself insteadthats a great way to Be Kind to Others. In addition, she is able to use the positive reinforcement methods with the peers interacting

202

JOLIVETTE AND STEED

TABLE 1 Examples of Positive Reinforcement Type Verbal positive Examples Way to go. I like the way you are sharing your toys. Great way to use your words to tell me what you want. Super job waiting your turn. Thumbs-up Smile/Wink High ve Hug Teacher helper Line leader Weekend pet caregiver Extra time on an activity A leisure book to take home A coloring book to take home A new box of crayons to take home Good job ribbon

Gestural

Downloaded by [Central U Library of Bucharest] at 05:02 05 January 2013

Social/Privilege

Tangible

with or in close proximity to Tania as well as other peers who are exhibiting similar problem behavior. When using verbal positive reinforcement, it is important to be specic by letting the child know what behavior you are reinforcing as it can be most effective in this manner (Sutherland, Wehby, & Yoder, 2002). If the verbal positive reinforcement did not increase Tanias adherence to the classroom rules, other types of positive reinforcement could be used. Gestural positive reinforcement can take many forms (Henley, 2006), and Ms. Schmidt may provide a hug, thumbs-up, or high ve, which is appropriate for this developmental age. Additionally, she could tap the corresponding pictorial classroom rule posted on the wall along with a thumbsup to make the connection between expected and displayed behavior. Social/privilege positive reinforcement also is effective (Kazdin, 2001). In Tanias case, Ms. Schmidt may extend playtime by calling her last to change activities for Tania if she continues to engage in appropriate behavior or may provide an opportunity for her to sit next to that same peer for the next activity. Another option is tangible positive reinforcement where an age-appropriate tangible is provided when Tania displays appropriate behavior. Tangibles can take many forms (e.g., a smiley sticker, a small piece of candy, a plastic necklace to wear for the duration of that activity period) and may make the connection between reinforcement and appropriate behavior more concrete for young children (Heal & Hanley, 2007). Tania may receive several small smiley stickers during the morning free-choice center time. When tangible positive reinforcement is used, it is critical that teachers use readily cost-effective items and that the tangibles be small and over time be traded for the other types of positive reinforcement that are more natural positive consequences for appropriate behaviors. Some argue that tangible reinforcement is not a good idea; however, if used judiciously, it can be effective in promoting behavioral change, especially when rst teaching the expected behaviors (Ingvarsson, Hanley, & Welter, 2009). Additionally, the various types of

CLASSROOM MANAGEMENT

203

Downloaded by [Central U Library of Bucharest] at 05:02 05 January 2013

positive reinforcement can easily be provided to small groups and whole classes of children when they display expected and appropriate classroom behavior. Positive reinforcement for young children is most effective when immediately given after the appropriate behavior so that the child can connect his or her specic appropriate behavior with the provided reinforcement (Malott & Trojan, 2008). Also it is important that the child be consistently reinforced for the appropriate behavior until the behavior becomes part of his or her natural behavioral repertoire. A teacher will know when the appropriate behavior is part of the childs repertoire based on the unsolicited, frequent use of the positive behaviors above initial levels in the original area of concern (e.g., for Tania it was morning center time) where the child displays the behavior on his or her own even in the absence of positive reinforcement from the teacher.

GROUP CONTINGENCIES One method to improve whole class appropriate behavior is to use group contingencies. Group contingencies can be a cost-effective and teacher energy saver when applied to children in a class as their peers, not the teacher, are the change agents (Tankersley, 1995). There are three group contingency classroom management strategies that teachers may use (Kerr & Nelson, 2010; Maag, 2004). First, the dependent group contingency strategy is when the class earns a reward based on the behavior of a single or small group of children. Second, the independent group contingency strategy is when children in the class receive a reward if they meet an individual performance criterion. Third, the interdependent group contingency strategy is when every child in the class must meet an individual performance criterion for the class to receive the reward. One way to use group contingencies is through the application of a token economy. A token economy, an example of an independent group contingency, can be effective in shaping childrens appropriate behavior. Also, it can be adapted to address different behaviors over time as the children develop. For example, Reitman, Murphy, Hupp, and Callaghan (2004) used an alternating treatments with a reversal design to determine the effectiveness of the STAR program (an individualized token system: children randomly selected as the stars for the session and their behavior determined whether or not the class received a reinforcer) versus the Group token contingency (a group token system: children other than the target children determined whether or not the class received the reinforcer) for three children in a Head Start center on their challenging behavior (noncompliance, disruption, negative child or teacher interactions). For two of the children, the individualized token economy appeared to be more effective and for the third child the group token economy was more effective in reducing challenging behavior. In another example, Murphy, Theodore, Aloiso, Alric-Edwards, and Hughes (2007) used a reversal design to determine the effects of an interdependent group contingency and mystery motivators (unknown reinforcers) on the disruptive behaviors of nine preschoolers exhibiting high and low levels of behavioral problems in a Head Start classroom. They found that all the children demonstrated decreases in disruptive behavior with effect sizes of 0.99 to 7.71. In addition, Murphy et al. (2007) hypothesized that this strategy also could be applicable for whole class implementation based on teacher acceptability ratings. Both of these studies highlight the applicability of group contingencies and token economies on improving the behaviors of young children in Head Start classrooms.

204

JOLIVETTE AND STEED

A token economy is a positive teacher-mediated strategy used to increase appropriate behaviors with four main principles. First, the teacher identies what challenging behaviors need to be addressed based on the individual child or classrooms needs. For instance, in Ms. Johnsons class the children are having difculties with turn taking and sharing toys during outside play and with turn taking and listening to others during story time. Ms. Johnson and her assistants nd themselves reprimanding multiple children during that time providing a venue for potential negative teacherchild interactions and relationships to develop. The teachers discuss what turn taking, sharing, and listening to others should look like for both outside and inside the classroom. This discussion is critical as the information will be shared with the children when the three behaviors are taught and modeled as well as used as verbal and visual reminders to the children when outside and inside (e.g., outside: We take turns and share our toys with others, and pictures exemplifying the two behaviors posted on the playground on the stairs next to the slide, on the pole next to the swings, and on the door to the storage bin for the loose toys; inside: Listening to others helps us know our friends better, and a picture of listening is posted on the bottom of the calendar next to the teachers story chair). In this case, the three behaviors for which the token economy will be used has been decided, dened, and taught with verbal and visual reminders present in the environment. Second, the physical tokens are dened. The token should be something that is easily portable in and outside the classroom for the teachers to access and provide to the children. For young children, the token also needs to be developmentally appropriate and safe for child use. The token is teacher controlled, meaning that the teachers are the only ones who can deliver the token reinforcement based on displays of the three appropriate behaviors. Taking these considerations into account, Ms. Johnson decided to use pom-poms. In addition, she decided that the adults could provide tokens based on whole class or individual compliance with the expected behaviors as well as deliver the tokens inside or outside the classroom. Ms. Johnson thought it would be important for the children to explicitly see the connection between their behavior, the expected behaviors, and token. Two medium-size shbowls were purchased with three lines drawn on each at the full, halfway, and one-quarter mark with one placed on top of the cubbies opposite but in view of the children sitting at story time and one placed on the windowsill on the playground next to the storage binboth very visible locations and out of reach of the children. Ms. Johnson also taught the children that all the adults would be watching for these behaviors and that pom-poms could be earned by one child, a group of children, or the whole class and all pom-poms would be placed into one of the shbowls. She determined that when a pom-pom was delivered that it needed to be done so in a visible and verbal manner (e.g., WowI am so proud of how the four of you are taking turns swinging or pushing each otherI am putting a pom-pom into the shbowl). She then monitored the number of pom-poms she and her assistants were initially providing as the children learned these new positive behaviors and to make sure that many pom-poms were given in both the inside and outside environments. Third, the reinforcers for the class earning a set number of tokens are dened. The actual reinforcers should be varied, change over time, and be of preference to the children whereas the number of tokens needed to access the reinforcers needs to be on a graduated scale. For this class, Ms. Johnson determined the reinforcer options by observing the children at play both inside and outside the classroom as well as making notes on what privileges the children requested. For the inside reinforcer options, the class could access via tokens a popcorn party (full shbowl), extra clothes for the dramatic play area, a new book in the class library (half a shbowl), or an extra snack

Downloaded by [Central U Library of Bucharest] at 05:02 05 January 2013

CLASSROOM MANAGEMENT

205

Downloaded by [Central U Library of Bucharest] at 05:02 05 January 2013

helping during the morning (very few pom-poms); the outside options were a walk/scavenger hunt in the neighborhood (full shbowl), extended (extra) playtime (half a shbowl), and access to special toys (e.g., hula hoops, nerf footballs, sidewalk chalk) not regularly available for the afternoon time (very few pom-poms). Ms. Johnson also decided to tie the amount of tokens needed to earn a reinforcer with some of the math concepts for the class (e.g., full/whole, half, quarter). By doing so, she was able to naturally teach math concepts required for the class and simultaneously address behavioral concerns. Fourth, an exchange system is created so the children know when they can cash in the tokens (pom-poms). For this class, Ms. Johnson set aside 10 min during Tuesday and Thursday story time (a) to review the three target behaviors with verbal examples of how some children displayed them with feedback for any error patterns, (b) for the class to count how many tokens were earned for inside and outside behavior, (c) to review how many tokens are needed for the various reinforcers, and (d) for the class to decide on whether to cash in the tokens for a smaller reinforcer or to save for the larger reinforcer. In this example, a simple token economy system was created whereby the children were taught and either individually or as a group reinforced for displaying the three target behaviors while also teaching the children math concepts and decision-making skills on how to use their tokens. The application of group contingencies with token economies can be effective in promoting the social growth of a classroom full of children with various emotional needs (Bushell, Wrobel, & Michaelis, 1968; Lefebvre & Strain, 1989; Murphy et al., 2007).

CHOICE MAKING Just as individuals like to be recognized for appropriate behavior, they also like to have the ability to make decisions regarding aspects of their day. This desire to make choices and thus have some say over ones environment is not unique to older persons or persons without challenging behavior. Young children also should be afforded the same opportunities to make choices as their peers, and if needed, the choice-making opportunities can be modied to meet their specic developmental needs (see Table 2; Bredekamp & Copple, 1997; Clark & McDonnell, 2008; McCormick et al., 2003). Opportunities for young children to make choices are an effective classroom management strategy that promotes skill building (e.g., cognitive, communication,

TABLE 2 How to Provide Choice-Making Opportunities to Young Children 1. Keep it simple by offering the child a few choices (e.g., 23 options). 2. Vary the methods of choice delivery (e.g., verbal, gestural, visual, tangible objects). 3. Consider the childs interests and preferences. 4. Embed choices into typical routines and activities. 5. Provide choices in close proximity to the child. 6. Match the types of choices to the situation. 7. Match the types of choices to the function of the challenging behavior. Sources. Bredekamp and Copple, 1997; Jolivette, McCormick, McLaren, and Steed, 2009; Jolivette, Stichter, Sibilsky, Scott, and Ridgley, 2002; Sigafoos, 1998.

206

JOLIVETTE AND STEED

Downloaded by [Central U Library of Bucharest] at 05:02 05 January 2013

motor, social) and social competence as well as successful manipulation of ones environment through appropriate behavior (Jolivette et al., 2004; McCormick et al., 2003). Choice making is the act of providing someone with more than one option related to a task or situation at hand and the actual provision of what one selects. The steps of providing choice-making opportunities are to offer a choice, ask the child to make a choice, wait for the child to make a selection, and reinforce the child with the selected choice (Sigafoos, Roberts, Couzens, & Kerr, 1993). McCormick et al. (2003, p. 9) provide ve guidelines for using choice making with young children that include: (a) choices must be valid and reasonable, (b) provide enough information so children can make wise choices, (c) respond to the childs choices, (d) choice does not mean complete freedom, and (e) consider the consequences. For example, during music time in Mr. Andersons Head Start classroom, the children commonly do not follow activity directions and instead run around the room, bang instruments on the oor, and yell when the music is on. Mr. Anderson consulted the mental health consultant from his facility and was told that providing choices can promote prosocial behavior and is a means to give structure and predictability to music time. After this discussion, Mr. Anderson decided to offer choices to the children prior to the activity, during the activity, and at the end of the activity. Prior to the activity, he may say, Today we are going to listen to some fun and happy songsshould we skip or march to the musicraise your hand only onceraise your hand if you want to skip, now raise your hand if you want to march, and the motion with the most hand raises would be modeled and reinforced. When transitioning during music time, Mr. Anderson may say, Now we are going to play an instrument to the songIm looking for good marchers and when I call your name you may choose which instrument you will play by sitting next to it. Near the end of the activity, he may say, Im looking for friends playing their instruments correctlyif I call your name put your instrument on the table and pick a friend to line up with. He would offer such choices within the natural ongoing routine without compromising the learning objectives of the particular music lesson.

PRECORRECTION A simple and effective classroom management method to address behavioral errors children may make in the classroom is to preempt predictable problem behavioral patterns. One such method is the use of precorrection. Precorrection includes verbal statements and explicit teaching of the expected appropriate behaviors prior to the children being asked to perform the behaviors in a specic context and before long patterns of behavioral problems have begun (Kerr & Nelson, 2006). For example, Stormont et al. (2007) investigated the effects of precorrection instruction and specic praise statements by the teacher during instructional periods on the externalizing problem behavior of 3- to 5-year-old children in a Head Start program already implementing PWPBIS. Results indicate that two of the teachers implemented precorrection at 100% for the intervention phase whereas the third had a mean implementation of 75%; all three teachers increased their rates of specic praise and the children in their classes rate of externalizing behavior problems decreased. A seven-step precorrection process (see Table 3), developed by Colvin, Sugai, and Patching (1993), provides a framework for teachers to teach and reinforce appropriate behavior prior to opportunities for continued child misbehavior.

CLASSROOM MANAGEMENT

207

TABLE 3 The Seven Questions to Answer for Precorrection Looking and teaching . . . 1. What is the predictable challenging behavior? 2. What is the expected appropriate behavior (e.g., classroom rule)? 3. What context modications will the teacher make? 4. What behavioral rehearsals of the expected behavior will be conducted? 5. What reinforcement methods and schedules will be put in place? 6. What types of prompts will be given to cue child-appropriate behavior? 7. How will the childs behavior be monitored?

Downloaded by [Central U Library of Bucharest] at 05:02 05 January 2013

Source. Colvin, Sugai, and Patching, 1993.

For example, after 2 weeks of school Mr. Tisdale has become concerned about the poor transitions his class is making between morning snack and story time. He is puzzled by this as the children often request story time and for more books to be read. When the children nish their snack in a staggered fashion, they are to brush their teeth and wash their hands, use the restroom, select a carpet square to sit on, remain on the carpet square until the story begins, and be quiet. Instead, the children wander about the classroom, play with off-limits items, and a few of them have engaged in physical aggression with one another. Because the children nish at different times and the adults are positioned at the snack table, sink area, and bathroom, there is no adult supervision at the carpet area. In addition, Mr. Tisdale has sometimes allowed the children to leave the snack table and then return instead of going to the carpet area. Mr. Tisdale decides to rst change the supervision patterns in the classroom so that there is an adult modeling the quiet sitting behavior on the carpet area when the rst child nishes with snack. Posters of the specic transition behaviors are made and posted by the sink as a visual prompt. In addition, while at the snack table each adult sings a made-up song detailing the appropriate steps (behavioral expectations) of leaving the snack area to sit on a carpet square. The adults also use verbal prompts reminding a child of the steps if the child is not following them. When the class follows the steps and displays appropriate behavior, Mr. Tisdale adds a letter to a Velcro boardwhen the word story is created the children earn a second story of their choice to be read that day. To monitor the effectiveness of the precorrection method, Mr. Tisdale puts the letter earned on his calendar for the day indicating that a second story is almost or was earned. That way, he can easily monitor how long it takes the class to earn a second story. In addition, it allows him an opportunity to observe any patterns (e.g., letters typically are not earned on Mondays and Thursdaysso what is different those days when precorrection is used) for which to remediate his precorrection plan. FUNCTIONAL COMMUNICATION TRAINING Many young children who have social skill problems and who display challenging behavior may have underlying language decits (e.g., Kaiser, Cai, Hancock, & Foster, 2002; Kaiser, Hancock, Cai, Foster, & Hester, 2000). Functional communication training (FCT) is one strategy that can be used effectively with young children with language decits who engage in problematic

208

JOLIVETTE AND STEED

Downloaded by [Central U Library of Bucharest] at 05:02 05 January 2013

behaviors. With this strategy, the children are taught an appropriate, alternative communicative response (e.g., verbal words, signs, gestures) to use in place of the challenging behavior. For example, the children may be taught to hold up a red card indicating a request for a break from circle time instead of leaving the area without permission or pinching the peer next to them as a means of taking a break. Halle, Brady, and Drasgow (2004) suggest that when using FCT with young children multiple alternative communicative responses be taught so as to build the childs language repertoire and to be exible given the variety of contexts in which the response may be used. In addition, it is important to teach alternative responses that are likely to be recognized and reinforced by peers, teachers, and families. In this example a red break card was a visual signal communicated by the child that would be easily recognized and reinforced by teachers and family members. In terms of peers, they will most likely need to be taught what the red card means and how they should behave if the children use them. In the previous example of Tania, her teacher decided to use FCT to make even greater improvements in Tanias peer relations. Because positive reinforcement as the primary strategy did not eliminate Tanias aggression during free choice center time, the teacher introduced Tania to two communication cards. If Tania placed the red side of a card in the block pointed at a peer, then her peers were taught to move a few inches away from her or to not interact with her until the red card was turned back to the green side. In this case, the green/red card provided Tania a more appropriate method of communicating her interaction needs instead of using aggressive behavior to meet the same need. ADAPTING CLASSROOM MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES INTO PWPBIS As teachers within early childhood settings implement research-based classroom management strategies and experience positive child results within their classrooms, they may want to consider scaling up their use of the strategies through PWPBIS (see NHSA Dialog 12[2], a 2009 special issue dedicated to PWPBIS). PWPBIS has emerged as a model of prevention to increase young childrens overall social growth and decrease challenging behaviors in early childhood settings including Head Start, preschool, and kindergarten classrooms (Powell, Dunlap, & Fox, 2006; Stormont, Lewis, & Beckner, 2005) by addressing the multiple contextual inuences on childrens challenging behavior (Sugai & Horner, 2001). In the eld of early childhood, a teaching pyramid has been created that includes four tiers: (a) foundational supports to build positive relationships with children, families, and colleagues; (b) primary, universal support consisting of classroom and program-wide interventions for all children; (c) targeted social, emotional teaching interventions for children who require explicit social skills interventions; and (d) intensive, individualized interventions for children who engage in severe and/or chronic challenging behavior (Fox et al., 2003; Sugai & Horner, 2001). When classroom management strategies are routinized and consistently implemented across school environments, children, and staff, improved child behaviors are observed (Feil et al., 2009). For this reason, effective classroom management strategies should be applied program-wide as this may (a) improve the overall number of children positively affected; (b) increase the effectiveness, efciency, and delity of implementation of the strategies across staff; (c) sustain the strategies over time; and (d) streamline the professional development activities for staff (Hemmeter & Fox, 2009). The classroom strategies presented are appropriate for adaptation across the tiers.

CLASSROOM MANAGEMENT

209

TRAINING AND ONLINE RESOURCES FOR CLASSROOM MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES AND PWPBIS In this article, we described and illustrated several empirically based classroom management strategies that could be implemented with efciency, ease, low cost, and minimal teacher training (see Table 4 for a summary) within preschool and Head Start programs for young children with challenging behaviors. Now, some educators may read this article and state that they already implement such strategies and that children in their classrooms continue to display problematic behaviors. Such a response is anticipated when adults are asked to change their instructional behavior. For example, Scott (2002) compiled a list of common teacher comments when presented with behavioral strategies to implement in their inclusive classrooms. Some of the comments included, My job is to teach academics, not behaviors, and I dont have time to provide prompts and reinforce behavior (pp. 2324). Scott contended that to address problematic child behavior, it is more efcient and effective to (a) prevent problem behavior from occurring, (b) collaborate and share decision making across fellow staff, (c) simultaneously teach school readiness and social skills within everyday contexts, and (d) monitor ongoing efforts and make changes when needed. Overall, Scott (2002) stated, [E]ffective instruction for all students is the job of the teacher and should never be looked upon as an extra duty or an unfair advantage for any student (p. 25). In some cases, teachers may want to engage in further professional development on the classroom management strategies presented in this article or others through a variety of venues to build their competence and condence in implementing them. For instance, teachers may want to learn more about classroom management strategies and PWPBIS through Internet-based, federally funded research technical centers through their teaching modules, publications/presentations, and public resources (e.g., Center on the Social and Emotional Foundations for Early Learning: www.vanderbilt.edu/csefel/; Council for Children with Behavioral Disorders: www.ccbd. net; IRIS Center: www.iriscenter.com; National Technical Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports: www.pbis.org; Technical Assistance Center on Social Emotional Intervention: www.challengingbehavior.org/; SpecialQuest Birth-Five: www.specialquest.org/; The Early Childhood Gateway: http://www.mdecgateway.org/; The National Professional Development Center on Inclusion: community.fpg.unc.edu/npdci). Other teachers may want to learn more through national conferences and workshops (e.g., Addressing Challenging Behavior National Training Institute on Effective Practices held each March in Florida, Association for Positive Behavior Support held twice a year, and the Pyramid Model Implementation Academy held in April in Florida). Ongoing professional development is critical for teachers as new classroom management strategies are proven effective for young children and as PWPBIS is adapted by more preschool and Head Start programs as a means to provide a consistent and supportive environment for young children who present challenging behaviors. SUMMARY There are various research-based classroom management strategies that teachers may use to reduce challenging behaviors and increase young childrens prosocial behavioral repertoires. The strategies presented are inherently exible in their use with an entire early childhood class, small groups of children, or individual children and can be used in combination to further promote

Downloaded by [Central U Library of Bucharest] at 05:02 05 January 2013

Downloaded by [Central U Library of Bucharest] at 05:02 05 January 2013

210

TABLE 4 Summary of Classroom Management Strategies Under Consideration Cost-Effectiveness Low (Tangiblemoderate) Minimal Teacher Training Literature Support High High Minimal Conroy, Sutherland, Snyder, Al-Hendaawi, & Vo, 2009 Lampi, Fenty, & Beaunae, 2005 Stormont, Smith, & Lewis, 2007 Skinner, Skinner, & Sterling-Turner, 2002 Tankersley, 1995 Moderate High Minimal Moderate (Dependent on reinforcer and number of children) Moderate (Dependent on reinforcer selections) Low High High Low Low Murphy, Theodore, Aloiso, Alric-Edwards, & Hughes, 2007 Minimal Jolivette, McCormick, McLaren, & Steed, 2009 Kern & State, 2009 McCormick, Jolivette, & Ridgely, 2003 Minimal Stormont et al., 2007 Moderate (Training may be Mancil, Conroy, & Nakao, 2006 needed for the functional assessment)

Strategy

Efciency in Ease of Addressing Problem Implementation

Positive reinforcement

High

Group contingencies

High

Token economy

High

Choice making

Moderate

Precorrection Functional communication training

High High

CLASSROOM MANAGEMENT

211

Downloaded by [Central U Library of Bucharest] at 05:02 05 January 2013

appropriate child behavior. Utilizing these classroom management strategies in the context of a model of positive behavioral interventions and supports ensures program-wide consistency and sustainability over time. One of the most critical functions in the early childhood classroom is for teachers to prepare and support their children as they develop and gain social competence (Hanley, Heal, Tiger, & Ingvarsson, 2007). The belief that young children who display challenging behaviors will independently and without intervention change their behavior on their own or grow out of it as they develop is false (Reichle et al., 1996). In fact, Conroy and Brown (2004) state, Until we reset our social priorities to acknowledge and better address young childrens behavioral and developmental needsparticularly the needs of children living in toxic environments with multiple, known risk factorsthe increase in the numbers of children who demonstrate chronic, pervasive, and severe problem behaviors is likely to continue (p. 233). Thus, teachers of young children and administrators of early childhood centers need to implement and monitor the effectiveness of classroom management strategies and PWPBIS on child behavior as a means to promote developmentally appropriate social growth.

REFERENCES

Alkon, A., Ramler, M., & MacLennan, K. (2003). Evaluation of mental health consultation in child care centers. Early Childhood Education Journal, 31, 9199. Benedict, E. A., Horner, R. H., & Squires, J. (2007). Assessment and implementation of positive behavior support in preschools. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 27, 174192. Bredekamp, S., & Copple, C. (1997). Developmentally appropriate practice in early childhood (Rev. ed.). Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children. Bushell, D., Jr., Wrobel, P. A., & Michaelis, M. L. (1968). Applying group contingencies to the classroom study behavior of preschool children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 1, 5561. Clark, C., & McDonnell, A. P. (2008). Teaching choice making to children with visual impairments and multiple disabilities in preschool and kindergarten classrooms. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 102, 397409. Coie, K. K., & Dodge, K. A. (1998). Aggression and antisocial behavior. In W. Damon & N. Eisenberg (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development (5th ed., pp. 779862). New York: Wiley. Colvin, G., Sugai, G., & Patching, B. (1993). Pre-correction: An instructional approach for managing predictable problem behaviors. Intervention in School and Clinic, 28, 143150. Conroy, M. A., & Brown, W. H. (2004). Early identication, prevention, and early intervention with young children at risk for emotional and behavioral disorders: Issues, trends, and a call for action. Behavioral Disorders, 29, 224236. Conroy, M. A., Sutherland, K. S., Snyder, A., Al-Hendaawi, M., & Vo, A. (2009). Creating a positive classroom atmosphere: Teachers use of effective praise and feedback. Beyond Behavior, 18, 1826. Durand, V. M., & Carr, E. G. (1991). Functional communication training to reduce challenging behavior: Maintenance and application in new settings. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 24, 251264. Feil, E. G., Walker, H., Severson, H., Golly, A., Seeley, J. R., & Small, J. W. (2009). Using positive behavior support procedures in Head Start classrooms to improve school readiness: A group training model and behavior training model. NHSA Dialog: A Research-to-Practice Journal for the Early Intervention Field, 12, 88103. Fox, L., Dunlap, G., Hemmeter, M. L., Joseph, G., & Strain, P. (2003). The teaching pyramid: A model supporting social competence and preventing challenging behavior in young children. Young Children, 58(4), 4852. Frey, A. (Ed.). (2009). Positive behavior supports and interventions in early childhood education [Special issue]. NHSA Dialog: A Research-to-Practice Journal for the Early Intervention Field, 12(2). Frey, A., Young, S., Gold, A., & Trevor, E. (2008). Utilizing a positive behavior support approach to achieve integrated mental health services. NHSA Dialog: A Research-to-Practice Journal for the Early Intervention Field, 11, 135156. Halle, J., Brady, N. C., & Drasgow, E. (2004). Enhancing socially adaptive communicative repairs of beginning communicators with disabilities. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 13, 4354.

212

JOLIVETTE AND STEED

Hanley, G. P., Heal, N. A., Tiger, J. H., & Ingvarsson, E. T. (2007). Evaluation of a class-wide teaching program for developing preschool life skills. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 40, 277300. Heal, N. A., & Hanley, G. P. (2007). Evaluating preschool childrens preferences for motivational systems during instruction. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 40, 249261. Hemmeter, M. L., & Fox, L. (2009). The Teaching Pyramid: A model for the implementation of classroom practices within a program-wide approach to behavior support. NHSA Dialog: A Research-to-Practice Journal for the Early Intervention Field, 12, 133147. Henley, M. (2006). Classroom management: A proactive approach. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. Ingvarsson, E. T., Hanley, G. P., & Welter, K. M. (2009). Treatment of escape-maintained behavior with positive reinforcement: The role of reinforcement contingency and density. Education and Treatment of Children, 32, 371401. Jolivette, K., McCormick, K. M., Jung, L. A., & Lingo, A. S. (2004). Embedding choices into the daily routines of young children with behavior problems: Eight reasons to build social competence. Beyond Behavior, 13, 2126. Jolivette, K., McCormick, K. M., McLaren, E., & Steed, E. B. (2009). Opportunities for young children to make choices in a model interdisciplinary and inclusive preschool program. Infants and Young Children, 22, 279289. Jolivette, K., Stichter, J. P., Sibilsky, S., Scott, T. M., & Ridgley, R. (2002). Naturally occurring opportunities for preschool children with or without disabilities to make choices. Education and Treatment of Children, 25, 396414. Kaiser, A. P., Cai, X., Hancock, T. B., & Foster, E. M. (2002). Teacher-reported behavior problems and language delays in boys and girls enrolled in Head Start. Behavioral Disorders, 28, 2339. Kaiser, A. P., Hancock, T. B., Cai, X., Foster, E. M., & Hester, P. P. (2000). Parent-reported behavioral problems and language delays in boys and girls enrolled in Head Start classrooms. Behavioral Disorders, 26, 2641. Kazdin, A. E. (2001). Behavior modication in applied settings (6th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. Kern, L., & State, T. M. (2009). Incorporating choice and preferred activities into classwide instruction. Beyond Behavior, 18, 311. Kerr, M. M., & Nelson, C. M. (2006). Strategies for addressing behavior problems in the classroom (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. Kerr, M. M., & Nelson, C. M. (2010). Strategies for addressing behavior problems in the classroom (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. Kohler, F. W., Strain, P. S., Hoyson, M., & Davis, L. (1995). Using a group-oriented contingency to increase social interactions between children with autism and their peers: A preliminary analysis of corollary supportive behaviors. Behavior Modication, 19, 1032. Kupersmidt, J. B., Bryant, D., & Willoughby, M. (2000). Prevalence of aggressive behaviors among preschoolers in Head Start and community child care programs. Behavioral Disorders, 26, 4252. Lampi, A. R., Fenty, N. S., & Beaunae, C. (2005). Making the three Ps easier: Praise, proximity, and precorrection. Beyond Behavior, 15, 812. Lefebvre, D., & Strain, P. S. (1989). Effects of a group contingency on the frequency of social interactions among autistic and nonhandicapped preschool children: Making LRE efcacious. Journal of Early Intervention, 13, 329341. Lewis, T. J., Hudson, S., Richter, M., & Johnson, N. (2004). Scientically supported practices in emotional and behavioral disorders: A proposed approach and brief review of current practices. Behavioral Disorders, 29, 247259. Lipsey, M. W., & Derzon, J. H. (1998). Predictors of violent or serious delinquency in adolescence and early adulthood: A synthesis of longitudinal research. In R. Loeber & D. P. Farrington (Eds.), Serious and violent juvenile offenders: Risk factors and successful interventions (pp. 86105). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Maag, J. W. (2004). Behavior management: From theoretical implications to practical applications. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. Malott, R. W., & Trojan, E. A. (2008). Principles of behavior. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Mancil, G. R., Conroy, M. A., & Nakao, T. (2006). Functional communication training in the natural environment: A pilot investigation with a young child with autism spectrum disorder. Education and Treatment of Children, 29, 615633. Mantzicopoulos, P. (2005). Conictual relationships between kindergarten children and their teachers: Associations with child and classroom context variables. Journal of School Psychology, 43, 425442. McCormick, K. M., Jolivette, K., & Ridgely, R. (2003). Choice making as an intervention strategy for young children. Young Exceptional Children, 6, 310. McLaren, E. M., Hall, P. J., & Fox, P. (2009). Kentuckys early childhood professional development initiative to promote social-emotional competence. NHSA Dialog: A Research-to-Practice Journal for the Early Intervention Field, 12, 170183.

Downloaded by [Central U Library of Bucharest] at 05:02 05 January 2013

CLASSROOM MANAGEMENT

213

Murphy, K. A., Theodore, L. A., Aloiso, D., Alric-Edwards, J. M., & Hughes, T. L. (2007). Interdependent group contingency and mystery motivators to reduce preschool disruptive behavior. Psychology in the Schools, 44, 5363. Muscott, H. S., Pomerleau, T., & Szczesiul, S. (2009). Large-scale implementation of program-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports in early childhood education programs in New Hampshire. NHSA Dialog: A Research-toPractice Journal for the Early Intervention Field, 12, 148169. Park, K. L., & Scott, T. M. (2009). Antecedent-based interventions for young children at risk for emotional and behavioral disorders. Behavioral Disorders, 34, 196211. Peacock Hill Working Group. (1991). Problems and promises in special education and related services for children and youth with emotional and behavioral disorders. Behavioral Disorders, 16, 299313. Powell, D., Dunlap, G., & Fox, L. (2006). Prevention and intervention for the challenging behavior of toddlers and preschoolers. Infants & Young Children, 19, 2535. Qi, C. H., & Kaiser, A. P. (2003). Behavior problems of preschool children from low-income families: Review of the literature. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 23, 188217. Raver, C. C., Jones, S. M., Li-Grining, C. P., Metzger, M., Champion, K. M., & Sardin, L. (2008). Improving preschool classroom processes: Preliminary ndings from a randomized trial implemented in Head Start settings. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23, 1026. Reichle, J., McEvoy, M., Davis, C., Rogers, E., Feeley, K., Johnston, S., et al. (1996). Coordinating preservice and in-service training of early interventionists to serve preschoolers who engage in challenging behavior. In R. Kogel, L. Kogel, & G. Dunlap (Eds.), Positive behavior support (pp. 227257). Baltimore: Brookes. Reitman, D., Murphy, M. A., Hupp, S. D., & OCallaghan, P. M. (2004). Behavior change and perceptions of change: Evaluating the effectiveness of a token economy. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 26, 1736. Scott, T. M. (2002). Removing roadblocks to effective behavior intervention in inclusive settings: Responding to typical objections by school personnel. Beyond Behavior, 12, 2125. Serna, L., Nielsen, E., Lambros, K., & Forness, S. (2000). Primary prevention with children at risk for emotional or behavioral disorders: Data on a universal intervention for Head Start classrooms. Behavioral Disorders, 26, 7084. Sigafoos, J. (1998). Choice making and personal selection strategies. In J. K. Luiselli & M. J. Cameron (Eds.), Antecedent control (pp. 187221). Baltimore: Brookes. Sigafoos, J., Roberts, D., Couzens, D., & Kerr, M. (1993). Providing opportunities for choice-making and turn-taking to adults with multiple disabilities. Journal of Development and Physical Disabilities, 5, 297310. Skinner, C. H., Skinner, A. L., & Sterling-Turner, H. E. (2002). Best practices in contingency management: Application of individual and group contingencies in educational settings. In A. Thomas & J. Grimes (Eds.), Best practices in school psychology IV (pp. 817830). Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists. Stormont, M. A., Lewis, T. J., & Beckner, R. (2005). Positive behavior support systems: Applying key features in preschool settings. TEACHING Exceptional Children, 37, 4249. Stormont, M. A., Smith, S. C., & Lewis, T. J. (2007). Teacher implementation of precorrection and praise statements in Head Start classrooms as a component of a program-wide system of positive behavior support. Journal of Behavioral Education, 16, 280290. Sugai, G., & Horner, R. H. (2001). Features of effective behavior support at the district level. Beyond Behavior, 11(1), 1619. Sutherland, K., Wehby, J., & Yoder, P. J. (2002). Examination of the relationship between teacher praise and opportunities for students with EBD to respond to academic requests. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 10, 513. Tankersley, M. (1995). A group-oriented contingency management program: A review of research on the Good Behavior Game and implications for teachers. Preventing School Failure, 40, 1925. Webster-Stratton, C., Reid, M. J., & Stoolmiller, M. (2008). Preventing conduct problems and improving school readiness: Evaluation of the Incredible Years teacher and child training programs in high-risk schools. Journal of Child Psychology, 49, 471488. West, J., Denton, K., & Reaney, L. M. (2001). The kindergarten year: Findings from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, kindergarten class of 19981999 (Publication No. NCES2001-023). Washington, DC: Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Willoughby, M., Kupersmidt, J., & Bryant, D. (2001). Overt and covert dimensions of antisocial behavior in early childhood. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 29, 177187.

Downloaded by [Central U Library of Bucharest] at 05:02 05 January 2013

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Edu356 Fba-2Dokument4 SeitenEdu356 Fba-2api-302319740100% (1)

- Inclusion and Placement Decisions For Students With Special NeedsDokument11 SeitenInclusion and Placement Decisions For Students With Special NeedsDaYs DaysNoch keine Bewertungen

- ED 124 - Healthy Foundations F08Dokument7 SeitenED 124 - Healthy Foundations F08Avneet kaur KaurNoch keine Bewertungen

- Edu-690 Action Research PaperDokument27 SeitenEdu-690 Action Research Paperapi-240639978Noch keine Bewertungen

- Youlia Weber - Trauma 101 For Educators - Eduu 602Dokument6 SeitenYoulia Weber - Trauma 101 For Educators - Eduu 602api-542152634Noch keine Bewertungen

- Matrix - Concept Attainment 2Dokument1 SeiteMatrix - Concept Attainment 2api-313394680Noch keine Bewertungen

- Parent Training Lit ReviewDokument16 SeitenParent Training Lit Reviewjumaba69100% (2)

- Formal Observation Report 1 1Dokument8 SeitenFormal Observation Report 1 1api-535562565Noch keine Bewertungen

- fspk2004 CD 4Dokument1 Seitefspk2004 CD 4api-234238849Noch keine Bewertungen

- Stakeholder ChartDokument7 SeitenStakeholder Chartapi-368273177100% (1)

- BBA (4th Sem) (Morning) (A) (Final Term Paper) PDFDokument5 SeitenBBA (4th Sem) (Morning) (A) (Final Term Paper) PDFZeeshan ch 'Hadi'Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cover LetterDokument2 SeitenCover LetterAditya Singh0% (1)

- Philippine Stock Exchange: Head, Disclosure DepartmentDokument58 SeitenPhilippine Stock Exchange: Head, Disclosure DepartmentAnonymous 01pQbZUMMNoch keine Bewertungen

- Is It Working in Your Middle School?: A Personalized System to Monitor Progress of InitiativesVon EverandIs It Working in Your Middle School?: A Personalized System to Monitor Progress of InitiativesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effects of an Inclusion Professional Development Model on Inclusion Knowledge and Perceptions of Regular Middle School EducatorsVon EverandEffects of an Inclusion Professional Development Model on Inclusion Knowledge and Perceptions of Regular Middle School EducatorsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alternate Assessment of Students with Significant Cognitive Disabilities: A Research ReportVon EverandAlternate Assessment of Students with Significant Cognitive Disabilities: A Research ReportNoch keine Bewertungen

- Interventions PDFDokument45 SeitenInterventions PDFJek EstevesNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4 3 Assignment 2 Pbs PlanDokument12 Seiten4 3 Assignment 2 Pbs Planapi-333802587Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ed5503 Final Project - Classroom ManagementDokument25 SeitenEd5503 Final Project - Classroom Managementapi-437407548Noch keine Bewertungen

- Personal and Professional IdentityDokument6 SeitenPersonal and Professional Identityapi-584626247Noch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding & Managing Social, Emotional & Behavioural Difficulties (SEBD)Dokument32 SeitenUnderstanding & Managing Social, Emotional & Behavioural Difficulties (SEBD)Racheal Lisa Ball'inNoch keine Bewertungen

- Classroom ManagementDokument25 SeitenClassroom ManagementHafeez UllahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Questions For Behaviour ObservationDokument2 SeitenQuestions For Behaviour ObservationDharsh ShigaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 7 MarzanoDokument3 SeitenChapter 7 MarzanoJocelyn Alejandra Moreno GomezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Defining Play-Based LearningDokument6 SeitenDefining Play-Based Learningapi-537450355Noch keine Bewertungen

- Iep Team ChartDokument5 SeitenIep Team Chartapi-315447031Noch keine Bewertungen

- Play Observation Ece 252Dokument6 SeitenPlay Observation Ece 252api-477646847100% (1)

- Pre Self Assessment Preschool Teaching PracticesDokument4 SeitenPre Self Assessment Preschool Teaching Practicesapi-497850938Noch keine Bewertungen

- Applying Structured Teaching Principles To Toilet TrainingDokument18 SeitenApplying Structured Teaching Principles To Toilet TrainingMabel FreixesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Academic Achievement in Relation To Metacognition and Problem Solving Ability Among Secondary School StudentsDokument14 SeitenAcademic Achievement in Relation To Metacognition and Problem Solving Ability Among Secondary School StudentsAnonymous CwJeBCAXp100% (1)

- Snell Kristya3Dokument9 SeitenSnell Kristya3api-248878022100% (1)

- Slade Et Al (2013) Evaluating The Impact of Forest Scholls A - A Collaboration Bet Ween A Universituy An A Primary SchollDokument7 SeitenSlade Et Al (2013) Evaluating The Impact of Forest Scholls A - A Collaboration Bet Ween A Universituy An A Primary SchollAna FerreiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 2 Inclusive Education in Early Childhood SettingsDokument7 SeitenModule 2 Inclusive Education in Early Childhood SettingsCalmer LorenzoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Importance of Care Routines in Early Childhood SettingsDokument3 SeitenThe Importance of Care Routines in Early Childhood Settingsapi-307622028100% (2)

- Running Head: Behavior Intervention Plan For Reducing Disruptive BehaviorsDokument25 SeitenRunning Head: Behavior Intervention Plan For Reducing Disruptive Behaviorsapi-239563463Noch keine Bewertungen

- Teachers Attitudes Toward The Inclusion of Students With AutismDokument24 SeitenTeachers Attitudes Toward The Inclusion of Students With Autismbig fourNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pico FinalDokument11 SeitenPico Finalapi-282751948Noch keine Bewertungen

- TuckerTurtle StoryDokument15 SeitenTuckerTurtle StoryjbonvierNoch keine Bewertungen

- sp0009 - Functional Assessment PDFDokument4 Seitensp0009 - Functional Assessment PDFMarlon ParohinogNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fba Part 1Dokument6 SeitenFba Part 1api-224606598Noch keine Bewertungen

- Best Practices OrignalDokument21 SeitenBest Practices Orignalapi-194749822Noch keine Bewertungen

- Baierl Task Analysis and Chaining ProjectDokument15 SeitenBaierl Task Analysis and Chaining Projectapi-354321926Noch keine Bewertungen

- Functional Behavioral Assessment: Date: - 3/25/20Dokument5 SeitenFunctional Behavioral Assessment: Date: - 3/25/20api-535946620Noch keine Bewertungen

- Positive Behaviour SupportDokument14 SeitenPositive Behaviour Supportapi-290018716Noch keine Bewertungen

- Philosophy of Classroom Management Final ResubmissionDokument7 SeitenPhilosophy of Classroom Management Final Resubmissionapi-307239515Noch keine Bewertungen

- Parent SST HandoutDokument4 SeitenParent SST Handoutapi-239565419Noch keine Bewertungen

- Childcare Power PointDokument12 SeitenChildcare Power Pointdwhitney100100% (1)

- Gartrell 01Dokument7 SeitenGartrell 01Aimée Marie Colomy0% (1)

- Functional Assessment Checklist For Prog PDFDokument76 SeitenFunctional Assessment Checklist For Prog PDFRishi SaxenaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Edu 361 BipDokument5 SeitenEdu 361 Bipapi-270441019Noch keine Bewertungen

- Information Sheet: Challenging Behaviour - Supporting ChangeDokument11 SeitenInformation Sheet: Challenging Behaviour - Supporting ChangeMadhu sudarshan ReddyNoch keine Bewertungen

- N G Behavior Intervention Plan Write UpDokument4 SeitenN G Behavior Intervention Plan Write Upapi-383897639Noch keine Bewertungen

- C 10Dokument27 SeitenC 10Jhayr PequeroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Empowering Learnsers Through Self-RegulationDokument50 SeitenEmpowering Learnsers Through Self-RegulationCarlo MagnoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guidance For Children and Young People With Social and Emotional and Behavioural DifficultiesDokument4 SeitenGuidance For Children and Young People With Social and Emotional and Behavioural DifficultiesfionaphimisterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Behavior Management .... Nicole Version - ScribdDokument6 SeitenBehavior Management .... Nicole Version - ScribdtbolanzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Monitoring BehaviorDokument9 SeitenMonitoring Behaviormazarate56Noch keine Bewertungen

- Artifact 5 - Iep AnalysisDokument7 SeitenArtifact 5 - Iep Analysisapi-518903561Noch keine Bewertungen

- Stead - Preference AssessmentDokument9 SeitenStead - Preference AssessmentRaegan SteadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Developmental Standards Handbook4 2013Dokument123 SeitenDevelopmental Standards Handbook4 2013api-213387477Noch keine Bewertungen

- Do Learning Stories Tell The Whole Story of Children S Learning A Phenomenographic EnquiryDokument14 SeitenDo Learning Stories Tell The Whole Story of Children S Learning A Phenomenographic EnquirycatharinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Well-Child Care in Infancy: Promoting Readiness for LifeVon EverandWell-Child Care in Infancy: Promoting Readiness for LifeNoch keine Bewertungen

- ADL BookletDokument121 SeitenADL BookletSnow. White19Noch keine Bewertungen

- (Ontario) 120 - Amendment To Agreement of Purchase and SaleDokument2 Seiten(Ontario) 120 - Amendment To Agreement of Purchase and Salealvinliu725Noch keine Bewertungen

- 9th SemDokument90 Seiten9th SemVamsi MajjiNoch keine Bewertungen

- StudioArabiyaTimes Magazine Spring 2022Dokument58 SeitenStudioArabiyaTimes Magazine Spring 2022Ali IshaanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Front Cover NME Music MagazineDokument5 SeitenFront Cover NME Music Magazineasmediae12Noch keine Bewertungen

- View of Hebrews Ethan SmithDokument295 SeitenView of Hebrews Ethan SmithOlvin Steve Rosales MenjivarNoch keine Bewertungen

- PrecedentialDokument41 SeitenPrecedentialScribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- D0683SP Ans5Dokument20 SeitenD0683SP Ans5Tanmay SanchetiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Term Paper General Principle in The Construction of StatutesDokument8 SeitenTerm Paper General Principle in The Construction of StatutesRonald DalidaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Continuous Improvement Requires A Quality CultureDokument12 SeitenContinuous Improvement Requires A Quality Culturespitraberg100% (19)

- Difference Between Reptiles and Amphibians????Dokument2 SeitenDifference Between Reptiles and Amphibians????vijaybansalfetNoch keine Bewertungen

- Empower Catalog Ca6721en MsDokument138 SeitenEmpower Catalog Ca6721en MsSurya SamoerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Things I'll Never Say - AVRIL LAVIGNEDokument1 SeiteThings I'll Never Say - AVRIL LAVIGNELucas Bueno BergantinNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4 Marine Insurance 10-8-6Dokument53 Seiten4 Marine Insurance 10-8-6Eunice Saavedra100% (1)

- Balfour DeclarationDokument6 SeitenBalfour DeclarationWillie Johnson100% (1)

- SAHANA Disaster Management System and Tracking Disaster VictimsDokument30 SeitenSAHANA Disaster Management System and Tracking Disaster VictimsAmalkrishnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- UntitledDokument256 SeitenUntitledErick RomeroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Excerpted From Watching FoodDokument4 SeitenExcerpted From Watching Foodsoc2003Noch keine Bewertungen

- Disbursement Register FY2010Dokument381 SeitenDisbursement Register FY2010Stephenie TurnerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acts and Key EventsDokument25 SeitenActs and Key Eventsemilyjaneboyle100% (1)

- Name: Joselle A. Gaco Btled-He3A: THE 303-School Foodservice ManagementDokument3 SeitenName: Joselle A. Gaco Btled-He3A: THE 303-School Foodservice ManagementJoselle GacoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hazrat Data Ganj BakshDokument3 SeitenHazrat Data Ganj Bakshgolden starNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rise of British Power in India Lec 5Dokument24 SeitenRise of British Power in India Lec 5Akil MohammadNoch keine Bewertungen

- EEE Assignment 3Dokument8 SeitenEEE Assignment 3shirleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Account Statement 2012 August RONDokument5 SeitenAccount Statement 2012 August RONAna-Maria DincaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wa0256.Dokument3 SeitenWa0256.Daniela Daza HernándezNoch keine Bewertungen

- S.No. Deo Ack. No Appl - No Emp Name Empcode: School Assistant Telugu Physical SciencesDokument8 SeitenS.No. Deo Ack. No Appl - No Emp Name Empcode: School Assistant Telugu Physical SciencesNarasimha SastryNoch keine Bewertungen

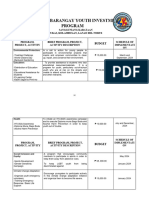

- Annual Barangay Youth Investment ProgramDokument4 SeitenAnnual Barangay Youth Investment ProgramBarangay MukasNoch keine Bewertungen