Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Cultural Studies and The Work of Pierre Bourdieu

Hochgeladen von

ipoulos69Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Cultural Studies and The Work of Pierre Bourdieu

Hochgeladen von

ipoulos69Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

French Cultural Studies http://frc.sagepub.

com/

'Cultural studies' and the work of Pierre Bourdieu

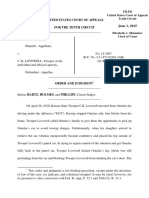

Morag Shiach French Cultural Studies 1993 4: 213 DOI: 10.1177/095715589300401203 The online version of this article can be found at: http://frc.sagepub.com/content/4/12/213

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for French Cultural Studies can be found at: Email Alerts: http://frc.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://frc.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://frc.sagepub.com/content/4/12/213.refs.html

Downloaded from frc.sagepub.com at Universiteitsbibliotheek Leiden on January 1, 2011

213-

Cultural studies and the work of Pierre Bourdieu

MORAG SHIACH*

a problem for of cultural studies in Britain, largely because it seems to discipline operate along the fault line between textual analysis and sociological critique which has for so long disturbed the disciplines self-constitution. When Nicholas Garnham and Raymond Williams talk of Bourdieu as offering a possible mediation between the traditions of cultural analysis represented by the Birmingham Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies and the film journal Screen, they seem to identify very precisely this difficulty, if perhaps expressing an exaggerated optimism about its possible resolution (Garnham and Williams 1980). The extent of the difficulty in assimilating Bourdieus work is perhaps signalled by his absence from so many texts which aim to define or develop the space of cultural studies in Britain: it is striking, for instance, that before the production of this special issue, no contributor to French Cultural Studies has drawn on the work of Pierre Bourdieu. The aim of this article is to indicate the lines of development in Bourdieus work which seem to have rendered it so problematic for British cultural studies. My argument will focus on the ways in which Bourdieu has theorized the possibilities of cultural resistance and of political pedagogies as well as on the ways in which his attempt to negotiate the pressures of determinism and agency have left his work marked by images of enclosure and entrapment.

Pierre Bourdieus work has always presented something of

the

Cultural studies and radical pedagogies

Cultural studies as a discipline exists within particular institutional sites: specifically those of secondary, further and higher education. It has, throughout its history, been defined not just in terms of the objects it studies but also in terms of a broader pedagogical and political project. Its aims of

address for correspondence: Dr Morag Shiach, Department of English, Queen Mary and College, University of London, Mile End Road, London E1 4NS.

Westfield

Downloaded from frc.sagepub.com at Universiteitsbibliotheek Leiden on January 1, 2011

214

challenging cultural hierarchies, of extending the range of cultural artefacts subjected to analysis or critique, and of undermining economistic understandings of the social formation are all to some extent congruent with the outlines of Bourdieus sociological investigations. Thus, in Choses dites, Bourdieu writes of the importance of disturbing analytic hierarchies, of his

intention to

dissoudre les grandes questions en les posant a propos socialement mineurs, voire insignifiants. (Bourdieu 1987: 30)

in

dobjets

a way that seems to legitimize cultural studies insistence on the social and cultural significance of the apparently ephemeral or banal. Similarly, his research in La Distinction offers a very precise analysis of the cultural and social mechanisms which have constructed the space of the aesthetic as one of privilege and of significant cultural capital. What Bourdieus work seems to undermine, however, is the desire of cultural studies to constitute itself as a site of resistance or transgression within institutions of education. Cultural studies has never been simply another discipline addressing a discrete set of objects, but has always sought to connect cultural analysis with the analysis of ideological structures and economic power. It has to that extent sought to embody the possibility of a radical pedagogy, the potential of educational institutions to empower or to avoid simple reproduction of the status quo. Much of Bourdieus early work is, of course, concerned with the viability of precisely such a project. In Les H6ritiers (1964) Bourdieu examines the failure of educational institutions to challenge the social inequalities which marked students on their entry into these institutions. Indeed, he shows the mechanisms by which educational institutions tend to reinforce such inequalities. These mechanisms operate crucially in relation to cultural knowledges, with universities, for example, tending to discount or even despise those cultural knowledges which are derived simply from the educational curriculum and to favour those knowledges whose source is mysterious, that is to say whose source lies in the experience of a specific class formation. The argument is continued in La Reproduction (1970) and connected even more emphatically with discourses of cultural evaluation and taste in La Distinction (1979). Over these three texts, however, Bourdieu becomes significantly less able to imagine an alternative to this practice of cultural and social reproduction. While Les Heritiers is marked by a sense of frustration at the failure of educational insitutions to deliver a practice of rational pedagogy or to develop something approaching a common culture, and at least imagines the possibility of rationally transmitting aristocratic culture within institutional contexts which might not be reinforcing a social hierarchy (Robbins 1991: 53), La Distinction sees hierarchy and the reproduction of social inequalities as precisely the business of cultural

Downloaded from frc.sagepub.com at Universiteitsbibliotheek Leiden on January 1, 2011

215

evaluation, and equates cultural evaluation or critique with a kind of symbolic violence. In La Distinction, taste is the expression of arbitrary

taxonomies which are mapped onto class-specific knowledges, and cultural evaluation is necessarily caught up in a mystifying assertion of its own autonomy. Such autonomy is illusory, and imaginable only within specific

cultural fields and at particular historical moments, yet intellectuals who operate within the field of cultural production or analysis are absolutely implicated in such idealist aesthetic discourses. Bourdieus work, then, has tended to show the way in which educational institutions collude in the reproduction of social inequalities and, far from seeing cultural analysis as a site of resistance or critique, has seen it as absolutely central to the project of social reproduction. Uncomfortably for cultural studies, it is not clear that this analysis can accommodate the desire of cultural studies to see itself as apart from such strategies of mystification and social stratification. It seems rather to offer a totalizing analysis of the function of all cultural discourses within educational institutions which can leave very little room for alternative pedagogies and grant very little power to attempts to modify the objects or methodologies of cultural analysis. We all seem to be playing the game of distinction, even as we seek to develop theoretical or methodological challenges to dominant literary modes of

analysis.

in Bourdieus work we find that there is very little alternatives to the cultural hierarchies which are so possible efficiently communicated and reproduced within educational institutions: what we are left with instead is a sense of enclosure. This is the dimension of Bourdieus work which has led some cultural theorists to condemn him as too sweeping or too mechanical in his social and cultural classifications:

Indeed, increasingly

of

sense

Having

written with such force... against forms of essentialism and substantialism in social theory, Bourdieu falls effortlessly into both when it comes to the aesthetic.

the working class [seems] to be within the cultural limits imposed

inevitably

on

and

inexorably entrapped

63 and

it.

(Frow 1987:

71)

Bourdieu is certainly aware of the problem, but cannot offer any political strategy within the realm of the cultural, which is so implicated in mechanisms of distinction. In so far as he can imagine an alternative pedagogy, it seems to be limited to the context of philosophy, where 1analyse des structures mentales est un instrument de liberation (Bourdieu 1987: 27). The rest of this article will be concerned to chart the implications of this refusal of the cultural as a space of possible transformation or critique and to consider the viability of Bourdieus search for un instrument de

Downloaded from frc.sagepub.com at Universiteitsbibliotheek Leiden on January 1, 2011

216

liberation in his analysis of what he social inequality: sexual difference.

sees as one

of the

founding

forms of

Populism or political modernism The tension within the discipline of cultural studies with which this article began can be characterized as a tension between populism and formalism, between the search for the popular as a site of resistance and the identification of strategies of formal textual subversion as the locus of political struggle. Neither position is without its difficulties, the first risking an over-politicization of popular culture and a consequent evacuation of considerations of form or value and the latter apparently over-formalizing the political so that questions of economic relations or institutions become invisible. Both, however, do offer a means by which the social criticism that has been the traditional province of the intellectual can be articulated

within the project of cultural studies (Wilson 1988: 55). In order to understand the difficulty that Bourdieus work poses for the discipline of cultural studies, despite its apparent congruence, it is necessary to consider the ways in which he condemns both political modernism and populism as simply strategies of distinction within the restricted field of intellectual or cultural production. In La Distinction, Bourdieu seeks to identify the mechanisms by which certain sorts of cultural discourses and knowledges become endowed with prestige, and thus constitute a form of cultural capital. His contention is that there is nothing inherent in aesthetic judgements or in discourses of taste that constitutes their rationale, other than their participation in a logic of scarcity: taste is something most people cant have. He points to the social and historical specificity of notions of the aesthetic as a separate sphere and of the idea that aesthetic experience constitutes a completely separate realm of experience, a different sort of looking or of feeling. In Les Regles de 1art (1992) he seeks to identify the historical development of notions of artistic autonomy more precisely, rejecting aesthetic theories which aim to identify some transhistorical essence of the aesthetic experience:

dessence se rencontrent sur 1essentiel, cest quelles ont de prendre pour objet... 1experience subjective de 1ceuvre dart qui est celle de leur auteur, cest-a-dire celle dun homme cultive dune certaine societe, mais sans prendre acte de Ihistoricit6 de cette experience et de lobjet auquel elle sapplique. Cest dire quelles oporent, sans le savoir, une universalisation du cas particulier et quelles constituent par la meme une experience particuliere, situee et dat6e, de lœuvre dart en norme transhistorique de toute perception artistique.

Si

ces

analyses

en commun

(Bourdieu 1992: 394).

Bourdieu thus tends

increasingly

to

deny

any substantive

meaning

to

Downloaded from frc.sagepub.com at Universiteitsbibliotheek Leiden on January 1, 2011

217

of taste or value, and to see them instead as simply the manifestation of the logic of a particular historically constituted cultural field. For Bourdieu, the emergence of the aesthetic as a separate sphere characterized by the pure gaze, by distance from the prevailing values of industrial capitalism, by self-reflexivity, or by autonomy, is simply part of a historical modification of commercial and class relations which took place in the mid-nineteenth century. It has no absolute claim to oppositional status or to essential truth. Indeed, the very claims of the aesthetic only make sense within very particular institutional sites or within a specific field. The idea that the aesthetic offers some escape from economic relations is misrecognition: instead it represents the articulation of economic relations and their connection with strategies of symbolic distinction. For Bourdieu, strategies of textual or formal experimentation within the realm of the aesthetic have no inherent claim to offer any form of resistance to the instrumentalism of capitalism. This conclusion clearly disturbs a critic such as Elizabeth Wilson, who invokes Adorno to support her claim that modernist texts have the capacity to produce radical transformations within both social and psychic reality (Wilson 1988: 48). Numerous critics have expressed a similar unease about Bourdieus apparently totalizing account of the project of modernism, which seems to offer no scope for considering the texts of modernist aesthetics as ambiguous or even as contradictory in their social and cultural significance. There is certainly a stark contrast between Bourdieus account of modernism as absolutely enclosed within the logic of a particular field of cultural production and the argument of Walter Benjamin in The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction which appears always to demonstrate the complexity and doubleness of the cultural impact of mass culture on the space of the aesthetic. For Bourdieu, modernist texts must always strive for distance and distinction:

judgements

La distanciation brechtienne pourrait 8tre 16cart par lequel 1intellectuel affirme, au coeur meme de 1art populaire, sa distance a 1art populaire qui rend 1art populaire intellectuellement acceptable... et, plus

profond6ment, sa distance au peuple. (Bourdieu 1979: 568)

Yet, for Benjamin, the

complex series of cultural transformations associated with technologies of mechanical reproduction offer instead the opportunity to break down the distance associated with the art object as cult object, and to explore the resources of immediacy and proximity for the development of a politicized conception of the aesthetic: The painter maintains in his work a natural distance from reality, the cameraman penetrates deeply into its web (Benjamin 1973: 235). What seems to be impossible on Bourdieus account is an analysis that sees the space of modernist aesthetics as ambiguous, as containing the

Downloaded from frc.sagepub.com at Universiteitsbibliotheek Leiden on January 1, 2011

218

potential both for subversion and for simple reproduction. One attempt to identify such complexity can be found in Peter Burgers distinction between modernism and the avant-garde, where modernism represents something closer to art for arts sake while the avant-garde embodies a substantial challenge to habits of perception and categories of thought and to the institution of art itself (Burger 1984). Similarly, Raymond Williams, while apparently endorsing much of Bourdieus account of the historical specificity of modernism as a social and cultural movement, still seeks to identify more precisely what is at stake in the texts and images of particular modernist artists (Williams 1989). For both Burger and Williams culture has the capacity to manifest a critical function, whereas for Bourdieu such a critical function is only another move in the coded game of cultural and social distinction. To stress the compulsion and inevitability of such game playing, Bourdieu has developed the concept of lillusio: Iadh6sion fondamentale au jeu... reconnaissance du jeu et de lutilite du jeu, croyance dans la valeur du jeu et de son enjeu (Bourdieu 1992: 245). This illusio serves to commit participants to the logic of a particular field and to its practices of distinction:

chaque champ produit sa forme sp6cifique dillusio, au sens dinvestissement dans le jeu qui arrache les agents a lindiff6rence et les incline et les dispose a operer les distinctions pertinentes du point de vue de la logique du champ. (Bourdieu 1992: 316)

totalizing analysis of the aesthetic leaves no room for exploiting cultural ambiguities as part of a politicized project of cultural analysis, but rather leaves us asking whether Bourdieus system allows anything to escape it and thus potentially to resist it? (Wilson 1988: 55). The difficulty with this critique, of course, is that Bourdieus work has already predicted it. Even to pose questions about the politics of modernism is to participate in a self-confirming game within the intellectual field. Bourdieu is equally critical of the capacity of high theory to deliver any sort of political critique, seeing it instead as simply another attempted monopoly of cultural capital. Theoretical accounts of the political potential of modernism are thus doubly disabled: they can never aspire to truth but only to legitimacy, which is to say to the rewards of discursive behaviour which corresponds precisely to the demands of a particular intellectual field. If the analysis of textual subversion can offer no sure basis for a politicized cultural studies, what then can we make of the claims of populism? Is it possible to imagine the popular as a site of resistance? For Bourdieu it would seem that it might be possible to imagine it, but it is not at all clear that it is possible to theorize or mobilize it. Bourdieu does at times seem to ground his critique of the aesthetic in a particular reading of the popular, as a space where practical and economic

or

Such a textual

Downloaded from frc.sagepub.com at Universiteitsbibliotheek Leiden on January 1, 2011

219

determine cultural forms and where a realist project of representation is vindicated in terms of its accessibility. Thus, for example, in Un art moyen (1965) Bourdieu stresses the manner in which photography as one of the popular arts subordinates questions of artistic form to considerations of its socially regulated functions and meanings. Elsewhere, Bourdieu appears to valorize the practicality of popular culture, its involvement in the everyday, as opposed to the distance from economic necessity and practical imperatives which characterize the realm of the aesthetic. It is perhaps in this aspiration to identify a cultural space which is not caught up in the logic of distinction that we can understand Derek Robbins judgement that Bourdieu operates with an unarticulated utopian

interests

vision

(Robbins: 176).

However, when it comes to an attempt to identify the political or theoretical meanings of the popular, Bourdieu is extremely sceptical. He points out the fluidity of the concept of the popular and its consequent

appeal to a diverse range of social critics, arguing that it owes

dans la production savante, au fait que chacun dans un test projectif, en manipuler inconsciemment 1extension pour 1ajuster a ses int6r6ts, a ses pr6jug6s ou a ses fantasmes

ses

vertus

mystificatrices,

1983:

peut,

comme

sociaux.

(Bourdieu

98)

It thus becomes impossible, for Bourdieu, to speak of the popular without being caught up in the realm of mythology. The aim of theorists seems to be to catch the essence of the popular, while Bourdieu stresses the need to see it as a contradictory and negotiated space. The desire to fix, and to claim, the popular is simply another manifestation of the struggle for distinction within the intellectual field. Debates about the politics of the popular only make est sense within such a restricted and restricting field: &dquo;le populaire&dquo;

...

dabord un des enjeux de lutte entre les intellectuels (Bourdieu 1987: 178). Thus, for Bourdieu, claims for a politicized reading of popular culture have no essential truth, but reflect rather the theorists place within the field of cultural production. Here too, then, we are disabled in the search for a politicized account of the space of cultural studies.

Gender and power

So far, Bourdieus analyses have served to disturb the capacity of cultural studies to represent itself as the space of a political critique. Instead of theorizing cultural analysis as a site of resistance to social and cultural hierarchies, Bourdieu tends rather to stress the ways in which it participates in mechanisms of distinction. His analyses serve to specify the terms of our enclosure rather than to offer us any escape. In order to see whether Bourdieu can imagine any analytic or practical

Downloaded from frc.sagepub.com at Universiteitsbibliotheek Leiden on January 1, 2011

220

strategies that might indeed offer us the instrument de liberation to which aspires, I want to turn finally to his analysis of what he describes as le paradigme (et souvent le modele et 1enjeu) de toute domination: la domination masculine (Bourdieu 1990: 31). Bourdieu sees gender relations as a key embodiment of the terms in which he seeks to theorize power. Drawing on his anthropological research, Bourdieu describes Kabyle culture as rigidly divided in terms of gender, with participation in rituals, division of labour, use of space and access to artefacts all clearly marked by differential gender relations. He describes Kabyle culture as one of phallonarcissism, where patterns of behaviour, use of time and categories of representation all serve to reinforce masculine power. Bourdieus interest lies in the ways in which this system of oppression sustains and reproduces itself, and in particular in the centrality of the symbolic domain. His argument is that such forms of oppression gain a kind of naturalness or inevitability from the power of sedimented rituals which are expressed in the habitus of members of the culture. The habitus here carries the meaning of both a predisposition to particular modes of behaviour and perception as well as a habitual mode of thinking. The habitus is marked on and by the body, which carries the weight and the meaning of gendered power relations. As such, it can be understood neither in terms of pure coercion nor in terms of willing consent. It is rather the space in which members of a culture negotiate its rituals, practices and meanings. Bourdieu once more stresses the enormous complexity of the system which maintains relations of inequality. In a manner strikingly, but perhaps surprisingly, reminiscent of the work of Helene Cixous (Cixous 1975), Bourdieu demonstrates the ways in which all categories of thought are marked by the hierarchy of sexual difference:

he

lopposition entre le masculin et le f6minin re~oit sa necessite objective et subjective de son insertion dans un systbme doppositions homologues, haut/bas, dessus/dessous. devant/derri6re, droite/gauche.

(Bourdieu

1990:

8)

While Cixous sets out to theorize and to develop a mode of writing which might challenge the inevitability of such hierarchized oppositions, such a strategy is impossible for Bourdieu. He can imagine no challenge to this cultural and social hierarchy from within the space of the cultural. Instead, he goes on to describe the ways in which gender relations, apparently immutable, have negative effects on all members of a culture. The image Bourdieu chooses to capture the pervasive impact of gender inequalities is once more one of enclosure:

les hommes sont aussi prisonniers, representation dominante, pourtant

int6r6ts.

et sournoisement

si

parfaitement

victimes, de la conforme a leurs

(Bourdieu 1990: 21)

Downloaded from frc.sagepub.com at Universiteitsbibliotheek Leiden on January 1, 2011

221

The ways in which gender inequalities distort and disable all members of a particular cultural group are crucial for Bourdieu, and he is critical of the failure of feminist research to address this issue. He does, however, exempt Virginia Woolf from this critique, seeing To the Lighthouse as a classic study of the ways in which masculinity tends to alienate and to infantilize those who are condemned to live under its sway. Bourdieus reading of To the Lighthouse is detailed and compelling, but once more it tends to diminish the critical potential of the cultural. Bourdieus reading focuses almost entirely on the character of Mr Ramsay, but it does so in a way that is curiously static. He has nothing to say about the character of Lily, who surely carries most of the transformative potential of the text, at both thematic and symbolic levels. Indeed, he tends to treat the novel as a series of descriptions rather than as a text that might embody contradiction or offer a formal challenge to the categorical differences with which it begins. The same kind of partiality emerges when Bourdieu considers what is at stake in womens exclusion from power within a patriarchal culture:

Les femmes ont le

se

privilege (tout n6gatifl de netre pas dupes des jeux ou disputent privileges, et de ny 6tre pas prises, au moins directement, en premiere personne. (Bourdieu 1990: 24)

les

seeing this exclusion as completely negative, Bourdieu loses any chance of exploring the potential of excluded groups for resistance, a possibility that Woolf herself was to theorize in Three Guineas. In relation to this paradigmatic system of power relations, then, Bourdieus analysis offers little by way of resistance. The ways in which symbolic and economic structures intersect is carefully laid out. The manner in which individual participants in a culture encounter such inequalities, and tend to reproduce them, is theorized through the concept of the habitus. But no challenge to this system seems possible within the space of the cultural: writing cannot set us free. Instead, Bourdieu ends with a call to collective action:

In

action collective visant a organiser une lutte symbolique de mettre en question pratiquement tous les presupposes tacites capable de la vision phallonarcissique du monde peut determiner la rupture de 1accord quasi imm6diat entre les structures incorporees et les structures

seule

une

objectiv6es. (Bourdieu 1990: 30)

The call is repeated in his conclusion to Les Regles de lart, where he speaks of the dangers of the erosion of the critical role of the intellectual. Once more, he argues that:

il est possible de tirer de la connaissance de la logique du fonctionnement des champs de production culturelle un programme realiste pour une action collective des intellectuels. (Bourdieu 1992: 461) J

Downloaded from frc.sagepub.com at Universiteitsbibliotheek Leiden on January 1, 2011

222

analysis is specifically addressed to those who can imagine the cultural comme instrument de liberte supposant la liberte (:462), a characterization that sits uneasily with the thrust of much of his own research. Clearly,

This Bourdieu believes that the stakes are now high, that the political power of the intellectual and the cultural power of reason are both under threat from ces nouveaux maitres a penser sans pensee (:470). He asks for a collective and international movement of intellectuals, aware of the historical constraints which shape their own discourses but committed to overcoming the division between autonomy and engagement and willing also to travailler collectivement a la defense de leurs int6r6ts propres (:472). Yet the site for such practical and symbolic struggle remains unclear: it may be sociology, it may be philosophy, but it seems unlikely that, for Bourdieu, it could ever be cultural studies.

LITERATURE CITED

Benjamin, Walter (1973),

The work of art in the age of mechanical

reproduction, in

Illuminations, edited by Hannah Arendt (London: Collins), 219-253 Bourdieu, Pierre and Jean-Claude Passeron (1964), Les Heritiers (Paris: Minuit) Bourdieu, Pierre, et al. (1965), Un art moyen: essais sur les usages sociaux de la

photographie (Paris: Minuit).

Bourdieu, Pierre (1970), La Reproduction: éléments pour denseignement (Paris: Minuit)

No. 46, 98-105.

une

théorie du

système

—— (1979), La Distinction: critique sociale du jugement (Paris: Minuit). —— (1983), Vous avez dit "populaire"?, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, —— (1987), Choses dites (Paris: Minuit). —— (1990) La Domination masculine, Actes de la recherche

No. 84,

en

sciences

sociales,

septembre, 2-31. —— (1992), Les Règles de lart: genèse et structure du champ littéraire (Paris: Seuil). Burger, Peter (1984), Theory of the Avant-Garde (Manchester: MUP).

Cixous, Hélène (1975), Sorties, in C. Clément and H. Cixous, La Jeune Née (Paris:

Union Générale dÉditions), 115-246. Frow, John (1987), Accounting for tastes: some problems in Bourdieus sociology of culture, Cultural Studies, i, 59-73. Garnham, Nicholas and Raymond Williams (1980), Pierre Bourdieu and the sociology of culture, Media, Culture and Society, ii, 209-223. Robbins, Derek (1991), The Work of Pierre Bourdieu (Milton Keynes: Open

University Press). Williams, Raymond (1989), The Politics of Modernism, edited by Tony Pinkney

(London: Verso).

Wilson, Elizabeth (1988), Picasso and Pâté de Foie Gras: Pierre Bourdieus Sociology of Culture, Diacritics, xviii, (2), 47-60.

Downloaded from frc.sagepub.com at Universiteitsbibliotheek Leiden on January 1, 2011

223

Woolf, Virginia (1992a), To the Lighthouse (Oxford: OUP)

A ), b —— (1992 Room of Ones Own and Three Guineas (Oxford: OUP).

Downloaded from frc.sagepub.com at Universiteitsbibliotheek Leiden on January 1, 2011

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (894)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- U.S Military Bases in The PHDokument10 SeitenU.S Military Bases in The PHjansenwes92Noch keine Bewertungen

- MS Development Studies Fall 2022Dokument1 SeiteMS Development Studies Fall 2022Kabeer QureshiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sexual Harassment Quiz Master With AnswersDokument4 SeitenSexual Harassment Quiz Master With AnswersTUSHAR 0131% (171)

- Germany S Triangular Relations With The United States and China in The Era of The ZeitenwendeDokument29 SeitenGermany S Triangular Relations With The United States and China in The Era of The ZeitenwendeAhmet AknNoch keine Bewertungen

- 04-22-14 EditionDokument28 Seiten04-22-14 EditionSan Mateo Daily JournalNoch keine Bewertungen

- ISBN9871271221125 'English VersionDokument109 SeitenISBN9871271221125 'English VersionSocial PhenomenaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ornelas v. Lovewell, 10th Cir. (2015)Dokument10 SeitenOrnelas v. Lovewell, 10th Cir. (2015)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Georgii-Hemming Eva and Victor Kvarnhall - Music Listening and Matters of Equality in Music EducationDokument19 SeitenGeorgii-Hemming Eva and Victor Kvarnhall - Music Listening and Matters of Equality in Music EducationRafael Rodrigues da SilvaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cook, David (2011) Boko Haram, A PrognosisDokument33 SeitenCook, David (2011) Boko Haram, A PrognosisAurelia269Noch keine Bewertungen

- LARR 45-3 Final-1Dokument296 SeitenLARR 45-3 Final-1tracylynnedNoch keine Bewertungen

- PENSION - Calculation SheetDokument5 SeitenPENSION - Calculation SheetsaurabhsriNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Judicial Branch MPADokument25 SeitenThe Judicial Branch MPAcrisjun_dNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case 1 The Caribbean Cooperative MovementDokument4 SeitenCase 1 The Caribbean Cooperative MovementReina TampelicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rhetorical Analysis of Sotomayor's "A Latina Judges Voice"Dokument4 SeitenRhetorical Analysis of Sotomayor's "A Latina Judges Voice"NintengoNoch keine Bewertungen

- LJGWCMFall 23Dokument22 SeitenLJGWCMFall 23diwakarNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Meaning ofDokument12 SeitenThe Meaning ofAnonymous ORqO5yNoch keine Bewertungen

- LBP Form No. 4 RecordsDokument2 SeitenLBP Form No. 4 RecordsCharles D. FloresNoch keine Bewertungen

- History of Delfin Albano IsabelaDokument4 SeitenHistory of Delfin Albano IsabelaLisa Marsh0% (1)

- Cambodia: in This IssueDokument11 SeitenCambodia: in This IssueUNVCambodiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Circassian Resistance To Russia, by Paul B. HenzeDokument32 SeitenCircassian Resistance To Russia, by Paul B. HenzecircassianworldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Election Cases (Digest)Dokument15 SeitenElection Cases (Digest)Rowneylin Sia100% (1)

- Sexual HarrassmentDokument6 SeitenSexual HarrassmentKristine GozumNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corruption in NigeriaDokument2 SeitenCorruption in NigeriaNike AlabiNoch keine Bewertungen

- ICOMOS, 2010. Working Methods and Procedures EvaluationDokument91 SeitenICOMOS, 2010. Working Methods and Procedures EvaluationCarolina ChavesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kimberly-Clark Worldwide v. Naty ABDokument5 SeitenKimberly-Clark Worldwide v. Naty ABPriorSmartNoch keine Bewertungen

- Professional Career: Carlo AngelesDokument3 SeitenProfessional Career: Carlo AngelesJamie Rose AragonesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Section 15 - Versailles To Berlin - Diplomacy in Europe PPDokument2 SeitenSection 15 - Versailles To Berlin - Diplomacy in Europe PPNour HamdanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Republic of The Philippines Barangay General Malvar - Ooo-Office of The Punong BarangayDokument2 SeitenRepublic of The Philippines Barangay General Malvar - Ooo-Office of The Punong BarangayBarangay Sagana HappeningsNoch keine Bewertungen

- RPH - Module 13 Assignment 1Dokument2 SeitenRPH - Module 13 Assignment 1Bleau HinanayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Agrarian & Social Legislation Course at DLSUDokument7 SeitenAgrarian & Social Legislation Course at DLSUAnonymous fnlSh4KHIgNoch keine Bewertungen