Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Duties of Public Prosecutor Towards Accused

Hochgeladen von

Shailaja RameshOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Duties of Public Prosecutor Towards Accused

Hochgeladen von

Shailaja RameshCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

DUTIES OF PUBLIC PROSECUTOR TOWARDS ACCUSEDhttp://livecricket.bollym4u.com/ indiansex4u M.A.Rashid, Advocate, High Court of Keralaip.indiansex4u.

com

IntroductionPregnancy Meditationhttp://nudeindiangirlsclub.com/ What is the most important right guaranteed under the Constitution of India to an accused in a criminal trial? It is a right to have a fair trial, which is a logical expansion of Article 21 of the Constitution of India. If the trial should be fair its conductor should be fair to both parties. A special feature of the administration of justice in the filed of criminal law in is that only a Public Prosecutor can prosecute the case against an accused. This is reflected in the mandate contained in section 225 of the Code of Criminal Procedure. There is no exception to this rule. Any private counsel engaged by the injured, or any advocate briefed by the relatives of the deceased however influenced they may be, is not entitled to conduct the prosecution in the sessions cases. This system is the glaring acknowledgment of the special status and position, which the office of Public Prosecutor is expected to wield in our legal system (Seethi Haji Vs State of Kerala 1986 KLT 1274). Public prosecutor is defined in section 2(u) of the Code as any person appointed under section 24 and includes any person acting under the direction of the Public Prosecutor. Thus a special Public Prosecutor also would be a Public Prosecutor in respect of a particular case or a class of cases for which he is appointed. The powers conferred on Public Prosecutor are seemingly so wide and unfettered that parliament reposed confidence of great magnitude in the office of the Public Prosecutor. Thus special status and position as well as great powers have been conferred on the office of the Public Prosecutor. Every Public Prosecutor has reminded himself constantly of his enviable position of trust and responsibility. [(Abdul Khader Vs. Government of Kerala 1992 (2) KLT 948)] The very object of section 225 of the Code of Criminal Procedure which insists that the sessions cases should be conducted by the prosecutor is explained in Karthik Ram Vs Emperor (AIR 1937 Nag 123) wherein the court held that the interest of the crown and the complainant are not always the same. Private parties often wish to serve their own private ends and the criminal proceedings are not primarily designed for that. It would be unfortunate to allow private passions and prejudices to creed into the conduct of a criminal trial, when it can be avoided. In Babu Vs State of Kerala (1984 KLT) 165 it is held that Public Prosecutors are really ministers of justice whose job is none other than assisting the state in the administration of justice. They are not representatives of any parties. Their job is to assist the court by placing before the court all the relevant materials. Though there is a plethora of judicial pronouncements of the apex court as well as of the various high courts the most elaborated one on the point is delivered by Thomas J. in Shiv Kumar Vs. Hukum Chand (1999 SCC (Cri) 1277). In the decision the court observed it is as well for the protection of the accused persons in sessions trial (in India) that provision is made to have the cases against him prosecuted only by a Public Prosecutor and not by any counsel engaged by any private party. Fairness to the accused who faces prosecution is a raison detre of the legislative insistence on that score. From the scheme of the Code the legislative intention is manifestly clear that prosecution in a sessions court cannot be conducted by anyone other than the Public Prosecutor. A Public Prosecutor is not expected to show a thirst to reach the case in the conviction of the accused some how or the other irrespective of the true facts involved in the case. The expected attitude of the Public Prosecutor while conducting prosecution must be couched in fairness not only to the court and to the investigating agencies but to the accused as well. If an accused is entitled to any legitimate benefit during trial the Public Prosecutor should not scuttle/conceal it. On the contrary, it is the duty of the Public Prosecutor to winch it to the fore and make it available to the accused. Even if the defence brings it to the notice of the court or it comes to his knowledge. (Emphasis supplied) An early decision of a full bench of the Allahabad High Court in Queen-Empress Vs Durga had pinpointed the role of a Public Prosecutor as follows: - it is duty of a Public Prosecutor to conduct the case for

the crown fairly. His object should be, not to obtain an unrighteous conviction, but, as representing the crown, to see that justice is vindicated; and in exercising his discretion as to the witnesses whom he should or should not call, he should bear that in mind. In our opinion, a Public Prosecutor should not refuse to call or put into the witness box for cross-examination a truthful witness returned in the calendar as a witness for the crown, merely because the evidence of such witness might in some respects be favourable to the defence. This remarkable observation was later followed by the Supreme Court in many of its judgments for deprecating the practice of giving up witnesses on the apprehension that they may turn hostile. In such a situation it is the duty of prosecutor to recourse to S 154 of Indian Evidence Act after calling him. High Court of Andhra Pradesh in Medichetty Ramakistiah V State of A.P. held that A prosecution, to use a familiar phrase, ought not to be a persecution. The principle that the Public Prosecutor should be scrupulously fair to the accused and present his case with detachment and without evincing any anxiety to secure a conviction is based upon high policy and as such courts should be astute to suffer no inroad upon its integrity. Otherwise there will be no guarantee that the trial will be as fair to the accused as a criminal trial ought to be. The State and the Public Prosecutor acting for it are only supposed to be putting all the facts of the case before the court to obtain its decision thereon and not to obtain a conviction by any means fair of foul. HISTORY In the early days, the Public Prosecutor was like any other counsel who would press for a verdict for his client. Over the years, the office was chiseled into a public office, J.L1.J Edwards in Law Officers of the Crown, has traced the growth of the office of the Public Prosecutor in . Prosecution of offences was left in the hands of private persons in that country, as noticed by Sir Fitz James Stephen in History Criminal Law. According to Sir Theobald Mathew, there was no Public Prosecutor in , in the true sense of the term. About the manner in which prosecution were conducted, Lord Chief Justice Campbell observed. The Criminal Law is most shamefully prevented to serve private purposes. The English pattern came to stay in . Today, it is beyond doubt that Public Prosecutor represents public interest, and that he acts as the minister of justice of the court. Kennys outline of criminal law gives a vivid picture of the office and its duties: A prosecuting counsel stands in a position quite different from that of an advocate who represents the person accused or represents a plaintiff or defendant in a civil litigation. But the crown counsel is a representative of the State, a minister of justice; his function is to assist the jury in arriving at the truth. He must not urge any argument that does not carry within his own mind, or try to shut out any legal evidence that would be important to the interest of the accused. Law commission of India in its 14th report on judicial administration while dealing with the subject of prosecution agency made certain recommendations in Para 12 of Ch XXXV of Vol.11, relevant extracts were reproduced belowIt is obvious that by the very fact of that being members of the police force and the nature of duties they have to discharge like bringing a case to court, it is not possible for them to exhibit that degree of detachment which is necessary in a prosecutor. It is to be remembered that their promotion in the department depends upon the number of convictions they are able to obtain as prosecuting officers. We therefore suggest that as a first step towards improvement, the prosecuting agency should be completely separated from the police department. These recommendations of the law commission were accepted by the Central Government and the parliament by enacting the code of procedure 1973 (Parliament Act 8 of 1974)made the necessary provision in Section 24 and 25 of Cr.P.C. The office of the Public Prosecutor is a very responsible office, which is an integral part of the machinery of Administration of Justice. Even the British never thought of placing them under the control of the police department as that would have robbed the Public Prosecutors of their objectivity in the conduct of trial of the cases and would have tarnished the fair name of justice. To repeat the

Law Commission in its XIV report had observed more than thirty years ago, as under: The integrity of a person chosen to be in charge of prosecution does not need to be emphasized. The purpose of a criminal trial being to determine the guilt or innocence of the accused person the duty of a public prosecutor is not to represent any particular party but the State. The prosecution of accused persons has to be conducted with the utmost fairness. In undertaking the prosecution, the State is not actuated by any motive of revenge but seeks only to protect the community. Thats why the National Police Commission in its 4th report recommended certain minimum qualifications for the posts of public prosecutors. These recommendations of the Police Commission also go to show that if the prosecuting agency were placed under the control of a police officer, a situation could be seen as likely to curtail freedom, as it would go against the principle of impartialities. The police having an interest in seeking that their work in investigation and arrest move to a conviction and there may be a temptation to suppress evidence to this end. Excessive zeal on the part of a prosecutor may result in placing the life and liberty of some citizens who were before the courts in jeopardy. With this objective in view of in view that the recommendations of the law commission and the National Police Commission which are based on the wisdom, maturity and rich experience gained during years, intended to confer on the prosecutor an independent discretion. In Sarala Vs Velu (2000) SCC 459 the Supreme Court deprecated the practice of seeking sanction from the prosecutor before filing the charge sheet. DUTIES OF PROSECUTOR TOWARDS ACCUSED DURING TRIAL A. Examination of witnesses In Darya Singh Vs State of Punjab (AIR 1965 SC 328) it is held that the prosecutor must act fairly and honestly and must never allowed the devise of keeping back from the court eye witnesses only because their evidence is likely to go against the prosecution case. The duty of the prosecutor is to assist the court in reaching a proper conclusion in regard to the case, which is brought before the trial. In (Shivaji Bodade Vs State of Maharashtra 1973 SCC (Cri) 1033) Krishna Iyer J. speaking for a three judge bench had struck a note of caution while a Public Prosecutor to pick and choose witnesses, he should be fair to the court, truth and to the accused. The Supreme Court reiterated the same position in Dalbar Kaur Vs State of Punjab (19786 SCC (Cri) 527) and in Hukkum Singh Vs State of Rajasthan (2000 SCC (Cri) 201). B. Giving copies to the accused In (1974 KLT 148 State of Kerala Vs Raghavan) it is held that Moreover, if the argument that the accused is not entitled to get copies of statements on which the prosecution does not seek to rely is accepted it would imply that the prosecution can, at its sweet will and pleasure pick and choose the statements of witnesses in respect of which the copies are to be, or are not to be, furnished to the accused to suit its convenience, thus eliminating all chances of the witnesses being confronted with their previous statements inconsistent with or contradictory to the case which the prosecution seeks to establish which could never be the intention of the legislature. If there is embellishment or contradictions in the statements given by the very same witnesses on different occasion, the veracity and trust worthiness of lthe witnesses have to be tested in cross examination with the aid of such materials to deny that would be to deny a just and fair trial to the accused. It should not certainly be the concern of the prosecution in such circumstances to deviate from or circumvent the relevant provisions incorporated in the code with view to ensure that the accused gets every opportunity to meet case brought against him. They are provisions based certain salutary principles of criminal jurisprudents to which, as the guardian of law, the court is found to adhere in its true spirits, even where the prosecution is tempted to keep the accused out of accesses to some of the documents which for his fair trial he is entitled to have.

C. Not to suppress material facts As per the provisions of Cr.P.C. and Indian Evidence Act there is a total prohibition in using a statement recorded under section 161 of Cr.P.C. except for contradicting a witness. When a material fact which is capable of proving the defence case or capable of creating reasonable doubt in the prosecution case is stated by a witnesses in a statement recorded by the police, the accused or his agents cannot use it if the Public Prosecutor decided not to examine that witnesses. Though the accused can examine that witnesses as defence witnesses, if that witnesses omitted to state that material fact the accused could not contradict with that previous statement as held in Tahsildar Singh Vs State of Punjab Air 1959 SC 1012. Though in Vincent Vs State of Kerala 1993 (1) KLT 777 it is held that the trial judge can put questions to witnesses so as to help the court to discover or to obtain proper proof of relevant facts u/s. 165 of Evidence Act though it is hit by section 162 Cr.P.C. the supreme court in Dandhu Lakshmi Reddy Vs State of Andhra Pradesh 1999 (3) KLT SN 41 held that even the power under section 165 of the Evidence Act is controlled by section 162 of Cr.P.C. Hence it is the duty of the prosecutor to draw the attention of the court to such material facts in order to avoid unmerited convictions. D. Avoid leading Questions6 In 1960 KLJ 546 (Kesavan & another Vs State of Kerala) P.T. Raman Nair.J. it is held that I might advert to the complaint for counsel for accused that when ever any of the so called eye witnesses gave an incomplete answer or an answer not to liking of the prosecutor, the prosecutor was allowed to elicit answers to his liking by the simple expedient of put in leading questions to the witnesses. The complaint I find is well founded, and I must take exceptions both the conduct of the Public Prosecutor in having put such questions and of the learned sessions judge in having allowed them. The position was reiterated by the supreme court in Varkey Joseph Vs State of Kerala (1993 (2) KLT 617) and it is further held that it is generally the duty of the prosecutor to ask the witnesses to state the facts or to give his own account of the matter making him to speak as to what he has been. The prosecutor will not be allowed to frame his question in such a manner that the witnesses answering merely yes or no will give the evidence which the prosecutor wishes to elicit. E. Avoid putting forth a new case different from the charge in surprise of the accused It is the duty of the prosecution to prove the prosecution story as alleged. It is not fair on the part of the prosecutor to create a prosecutors story. It must stand on its own legs as held in (AIR 1976 SC 975 Bhageerath Vs State of MP). It cannot take advantage of the weakness of the defence or make out a new case for the prosecution and convict the accused on that basis. It is also not fair on the part of the prosecution to rely on the admissions made by the counsel for the accused during the cross-examination. As held in 1982 KLT 605 it is no part of the duty of the Public Prosecutor to secure by unfair means or foul, conviction in any case. He has to safe guard public interest in prosecuting the case, public interest also demands that the trial should be conducted in a fair manner, needful of the rights granted to the accused under the laws of the country. The prosecutor while being fully aware of the duty to prosecute the case vigorously and also is prepared to respect and protect the accused. F. Section 38 of Cr.P.C. and the duty of the prosecutor As per sections 306 and 307 a magistrate or a trial judge, as the case may be have the power to grant pardon to an accused with a view to obtaining evidence in cases where the conviction of any accused is otherwise not possible. Though the prosecutor has no role with the process of granting pardon to an accused when a person accepted a pardon, either by wilfully concealed anything

essential or by giving false evidence, or not complied with the condition on which the pardon was made he can be tried for the offence and also for the offence of giving false evidence only when the Public Prosecutor certifies that he violated the conditions. So the right to fair trial to an accused in these types of cases was totally controlled by the power of prosecutor. Even when an approver totally exculpate himself and exaggerate the case against the others the accused persons could not challenge the tendering of pardon unless the prosecutor certifies that approver violated the condition of pardon. Hence it is the duty of prosecutor to observe carefully the conduct of the approver and his statements with a view to make it sure that the accused persons also get fair trial. G. Role of prosecutor in withdrawal from prosecution. The full bench of the Kerala High Court in Deputy Accountant General Vs State of Kerala AIR 1970 KER 158(FB) held that by incorporating the section in the statute book the legislature gave a wide power to the public prosecutor to withdraw an accused from the prosecution. When the parliament conferred the wide discretion envisaged under section 321 of Code on a public prosecutor a special confidence has been reposed in his high office that the discretion would not be exercised unfairly or defeating the administration of the criminal justice. Hence the prosecutor should apply his mind independently and must be fair to the accused also.

Public prosecution in India

Dr K N Chandrasekharan Pillai, Director, Indian Law Institute, New Delhi In organized societies, there is a public prosecution system to prosecute offenders who violate societal norms. The system in common law countries differs from that in the continental countries, but in both, this office is a centre of attraction, a power centre. It wields a lot of authority. It is the repository of the public power to initiate and withdraw prosecution. These powers are untrammeled in continental counties, where this office is called procurator. The word procurator is derived from the Latin word procuro, which means I care, secure, protect. Though the prosecutors in the common law countries do not carry these adulations, it appears the powers exercised by procurators are similarly understood to be available to the prosecutors in common law countries. However, many of the main powers are not available. In continental countries the procurator is looked upon as the strict eye of the state. He prohibits, punishes and prevents. The defence lawyer is viewed as defender. One of the procurators chief functions must be to protect citizens legitimate rights and interests with actions, not words, as prescribed by the law. The impression that the procurator is independent and impartial is accepted in the common law countries though in fact in these countries they may not be impartial. Even in the face of statutory provisions to the contrary, their traditional rights like nulle prosequi are accepted. Therefore, generally speaking, it could be said that the prosecution system in common law countries works within the statutory provisions in the context of traditional powers and duties attached to this office in continental countries. In India, we have a public prosecutor who acts in accordance with the directions of the judge. The control of trial is in the hands of the trial judge. Investigation is the prerogative of the police. The decision to prosecuteXa function attributed to the procurator in continental countriesXis taken in India by the magistrate on the report submitted by the police. Again, the withdrawal of the prosecution can also be done only with the permission of the court. However, it is generally believed that traditional right of nulle prosequi is available to the prosecutor. Being an officer of the court, the prosecutor is believed to represent the public interest and as such not to seek conviction of a party by hook or crook. The prosecutor is supposed to lead evidence favourable to the accused for the benefit of the court, not conceal it to secure a conviction. It is also believed that in a case of withdrawal of prosecution, if the prosecutor makes an independent decision to withdraw a case then the court should accept this and permit withdrawal under section 321 of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC). Section 24 of the CrPC provides for appointment of public prosecutors in the High Courts and the district by the central government or state government. Subsection 3 lays down that for every district, the state government shall appoint a public prosecutor and may also appoint one or more additional public prosecutors for the district. Subsection 4 requires the district magistrate to prepare a panel of names of persons considered fit for such appointment, in consultation with the sessions judge. Subsection 5 contains an embargo against appointment of any person as the public prosecutor or additional public prosecutor in the district by the state government unless his name appears in the panel prepared under subsection 4. Subsection 6 provides for such appointment wherein a state has a local cadre of prosecuting officers, but if no suitable person is available in such cadre, then the appointment has to be made from the panel prepared under subsection 4. Subsection 4 says that a person shall be eligible for such appointment only after he has been in practice as an advocate for not less than seven years. Section 25 deals with the appointment of an assistant public prosecutor in the district for conducting prosecution in the courts of magistrate. In the case of a public prosecutor also

known as district government counsel (criminal) there can be no doubt about the statutory element attached to such appointment by virtue of this provision in the CrPC 1973. In this context, section 321 of the CrPC is also relevant. As already mentioned, it permits withdrawal from prosecution by the public prosecutor or assistant public prosecutor in charge of a case with the consent of the court at any time before the judgment is pronounced. This power of the public prosecutor in charge of case is derived from the statute and must be exercised in the interest of the administration of justice. There can be no doubt that this function of the public prosecutor relates to a public purpose entrusting the officer with the responsibility of so acting only in the interest of administration of justice. The nature of the powers of the public prosecutor is sometimes doubted. At times, it appears to be executive power. In certain contexts, it may appear to be quasi-judicial. The principle that the Supreme Court laid down in R K Jains case (AIR 1980 SC 1510), quoting Shamsher Singh v. State of Punjab [(1974) 2 SCC 831), as regards the meaning and content of executive powers tends to treat the public prosecutors office as executive. But the conclusions of some courts create doubt as to its exact nature. To the suggestion that the public prosecutor should be impartial (a judicial quality), the Kerala High Court equated the public prosecutor with any other counsel and responded thus: Every counsel appearing in a case before the court is expected to be fair and truthful. He must of course, champion the cause of his client as efficiently and effectively as possible, but fairly truthfully. He is not expected to be impartial but only fair and truthful. [Aziz v. State of Kerala (1984) Cri. LJ 1060 (Ker)] In a subsequent decision, however, the same high court had to distinguish between a public prosecutor and a counsel for the private party thus: Public prosecutors are really ministers of justice whose job is none other than assisting the state in the administration of justice. They are not representatives of any party. Their job is to assist the court by placing before the court all relevant aspects of the case. They are not there to use the innocents go to the gallows. They are also not there to see the culprits escape conviction. But the pleader engaged by a private person who is a defacto complainant cannot be expected to be so impartial. Not only that, it will be his endeavor to get the conviction even if a conviction may not be possible. [Babu v. State of Kerala (1984) Cri. LJ 499 (Ker) at 502] indiansex4u Though the office of the public prosecutor seems to have the features of the executive, the judiciary does not appear to treat it so, because it does not approve of the appointment of police officers as public prosecutors. The Punjab & Haryana High Court in Krishan Singh Kundu v. State of Haryana [1989 Cri. LJ 1309 (P&H)] has ruled that the very idea of appointing a police officer to be in charge of a prosecution agency is abhorrent to the letter and spirit of sections 24 and 25 of the Code. In the same vein the ruling from the Supreme Court in SB Sahana v. State of Maharashtra [(1995) SCC (Cri) 787] found that irrespective of the executive or judicial nature of the office of the public prosecutor, it is certain that one expects impartiality and fairness from it in criminal prosecution. The Supreme Court in Mukul Dalal v. Union of India (1988 3 SCC 144) also categorically ruled that the office of the public prosecutor is a public one and the primacy given to the public prosecutor under the scheme of the court has a social purpose. But the malpractice of some public prosecutors has eroded this value and purpose. In Sunil Kumar Pal v. Phota Sheikh [(1984) 4 SCC 533] the Supreme Court was presented with a peculiar situation. In this case, some miscreants murdered the appellants brother and there were

virtually no subsequent proceedings against the accused for quite some time. The appellant was not present in India to pursue the case vigorously. When he came to India, he approached the state government to expedite things. Due to his persistence, one lawyer was appointed as a special public prosecutor. He approached the session court judge trying for an adjournment, as he had no records with him. He was granted only a day and he returned the briefs, as he did not have sufficient time to prepare for the case. Then the junior of the public prosecutor in the area was appointed as special public prosecutor for this case. He was also given a day for preparation before the commencement of the trial, in which it was astonishing to find that the nine accused were represented by the public prosecutor of the area! The trial was a farce. Supporters of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) assembled around the court and shouted slogans against the prosecution. Witnesses were intimidated and several did not turn up. Some turned hostile. The accused were acquitted. The appellants prayer for leave to appeal was rejected. The Calcutta High Court also rejected his appeal under section 401. Then he approached the Supreme Court with special leave. The court set aside the order of acquittal after making a survey on the administration of the lower court and in paragraph 10 observed thus: The order passed by the learned additional sessions judge acquitting respondent nos. 1 to 9 obviously suffers from a serious infirmity and we do not think it is possible to sustain it on any view of the matter. There can be little doubt that the trial culminating in the acquittal of respondent nos. 1 to 9 was appallingly unfair so far as the prosecutions is concerned and was heavily loaded in favour of respondent nos. 1 to 9. It is difficult to understand how consistently with ethics of the legal profession and fair play in the administration of justice, the public prosecutor of Nadia could appear on behalf of respondent nos. 1 to 9. The appearance of the public prosecutor, Nadia on behalf of the defence does lent support to the allegation of the appellant that respondent nos. 1 to 9 were supported by the Communist Party of India (Marxist) which was at the material time the ruling party in the State of West Bengal and this would naturally give rise to apprehension in the minds of the witnesses that in giving evidence against respondent nos. 1 to 9, they would be not only incurring the displeasure of the government but would also be fighting against it. Moreover, it cannot be disputed that when the trial was going on and the witnesses were giving evidence, there were a large number of supporters of the Communist Party (Marxist) who were allowed to assemble in the court compound and who created a hostile atmosphere by shouting against the prosecution and in favour of the accused. Though the appellant and the complainant as also the witnesses were intimated, no steps were taken for according protection to them so that they may be able to give evidence truly and fearlessly in proper atmosphere consistent with the sanctity of the court. It is significant to note that quite a few witnesses turned hostile and that obviously must have been due to the fact that they apprehended danger to their life at the hands of respondent nos. 1 to 9 and their supporters. It is also regrettable that though at the time when the trial commenced on 22nd May, 1978, Shri S. N. Ganguly, who was appointed special public prosecutor to conduct the prosecution, asked for an adjournment of the trial in order to enable him to prepare the case particularly since he was appointed on 20th May, 1978, the trial was adjourned only for one day, with the result that S. N. Ganguly had to return the relief. Then late in the evening of 22nd May 1978 Shri S. S. Sen, additional public prosecutor was asked to conduct the prosecution and he had to begin the case on the very next morning on 23rd May 1971 without practically any time for effective preparation. We have no doubt that under these circumstances the trial was heavily loaded in favour of respondent nos. 1 to 9. The trial must in the circumstances be held to be vitiated and the acquittal of respondent nos. 1 to 9 as a result of such trial must be set aside. It is imperative that in order that people may not loose faith in the administration of criminal justice, no one should be allowed to subvert the legal process. No citizen should go away with the feeling that he could not get justice from the court because the other side was socially, economically or politically powerful and could manipulate the legal process. That would be subversive of the rule of law. This decision reflects on the poor administration of criminal justice in India. A partisan government

may cause a breakdown of the constitutional order. It also shows that unless the state has an independent prosecution agency, the administration of justice might suffer irreparably. It has been the consistent policy of the appellate courts that it is the prerogative of the public prosecutor to recommend withdrawal of prosecution. Indeed, this prerogative right is to be exercised with the permission of the court. And it is the impression, having regard to the case law, that if the public prosecutor comes up with the proposal of withdrawal independently, i.e., without being influenced by the government, the court may grant permission. The courts reiterate this principle time and again, even in cases where permission is refused. In State of Punjab v. Union of India [1987 Cri. L.J 151 (SC)], the Punjab & Haryana High Court ruled that public prosecutors withdrawal from prosecution could follow not only from the paucity of evidence but also in order to further the broad ends of public justice, which may include appropriate social, economic and political purposes. In R K Jain v. State (AIR 1980 SC 1510), the Supreme Court sketched out the contours of the public prosecutors power for withdrawal of cases. In Shonandan Paswan v. State of Bihar [(1987) 1 SCC 288] and in Mohd. Mumtaz v. Nandini Satpathy [1987 Cri. L.J. 778 (SC)], the Supreme Court ruled that the public prosecutor can withdraw a prosecution at any stage and that the only limitation is the requirement of the consent of the court. Even when reliable evidence has been adduced to prove the charges, the public prosecutor can seek the consent of court to withdraw prosecution. The court specifically ruled that it should be seen whether application for withdrawal is made in good faith, in the interests of public policy and justice and not to thwart or to stifle the process of law. The Madras High Court was confronted with a case wherein the same office of the public prosecutor that had a criminal case withdrawn with permission of the court after a change of government moved the court to reopen prosecution. Fortunately, the judge did not permit it, and added a sad commentary on the functioning of the public prosecutor thus: I feel that the same office of the public prosecutor which acted for the state to withdraw the cases, cannot come forward to set aside the order permitting to withdraw the cases, irrespective of the change in the ruling party as it will lead to uncertainty as to the finality of the proceedings when the government, ruled by a particular party, withdraws the prosecution and the successive governments, ruled by another party, wanted to set aside that order, what will be the situation, if there were successive changes in the ruling parties and if this request is allowed, certainly it will be a havoc and prejudice to the accused persons, without knowing the destination of the prosecution apart from the embarrassment to the public prosecutors. Therefore, I also feel that the state which moved for withdrawing the prosecution cannot seek to set aside the order of permission granting withdrawal of the prosecution. If a third party comes forward with such a prayer the position may be different. [State of TN v. Ganesan, 1995 Cri. L.J 3849 (Mad) at 3851] The Supreme Court in a later case viz. V. S. Atchulthanandan v. R. Balakrishna Pillai [(1994) 4 SCC 299] allowed the petition of a third party to annul the High Courts order permitting withdrawal of prosecution against the respondent. It was with the active support of the state government that the prosecution against the respondent, a former minister, was permitted to be withdrawn. The opposition leader challenged this order in the Supreme Court. The court accepted his plea and set aside the order. Of late, there has been a change of approach to public prosecution. With the advent of partisan politics, political parties tend to interfere with administration of justice, including appointment of public prosecutors and determination of their functions. The decisions in Sunil Kumar Pal, Ganesan and Atchulthanandan speak to the changes and the responses of the judiciary. It seems that the office of the public prosecutor belongs to the executive. However, it is strongly felt

that it is in fact not purely of the executive. As explained by the Supreme Court in the Shamsher Singh, it takes on judicial character and as such assumes a lot of importance in a democracy. The very establishment of this office presupposes the understanding that we cannot afford to permit private prosecution as it may result in utter chaos, particularly in the present political set up. However, while we adopt this office in the place of private prosecution, we cannot forget the interests of the victim. The public prosecutor may not share the concerns of the victim, or safeguard the victims interests. The Indian CrPC therefore permits pleaders appointed by private persons to represent the interests of victims. However, the courts insist that they should work under the directions of the public prosecutor. This shows that the court gives more importance to the public interest. The public prosecutor in India does not seem to be an advocate of the state in the sense that the prosecutor has to seek conviction at any cost. The prosecutor has to be impartial, fair and truthful, not only as a public executive but also because the prosecutor belongs to the honourable profession of law, the ethics of which demand these qualities. The facts in Sunil Kumar Pal and Ganesan make us to open our eyes to the realities. The difficulties arising where public prosecutors are appointed on the basis of political affiliations also came before the Supreme Court in Kumari Srilekha Vidyarthi v. State of UP [(1991) 1 SCC 212]. The Supreme Court deprecated this trend and said that appointment to such vital offices should not be allowed on the basis of political party preferences. But even today, state governments distribute these offices among their sympathizers. And after assuming office many incumbents feel that they need to look after the interests of the ruling party. The parliament amended the CrPC so that state governments could adopt prosecution services consisting of a director of public prosecutions at the top and district public prosecutors and assistant public prosecutors at the lower formations. Section 25A inserted by Act 25 of 2005, section 4 (with effect from 23 June 2006) lays down that: 25A. Directorate of Prosecution V (1) The State Government may establish a Directorate of Prosecution consisting of a Director of Prosecution and as many Deputy Directors of Prosecution as it thinks fit. (2) A person shall be eligible to be appointed as a Director of Prosecution or a Deputy Director of Prosecution, only if he has been in practice as an advocate for not less than ten years and such appointment shall be made with the concurrence of the Chief Justice of the High Court. (3) The Head of the Directorate of Prosecution shall be the Director of Prosecution, who shall function under the administrative control of the Head of the Home Department in the State. (4) Every Deputy Director of Prosecution shall be subordinate to the Director of Prosecution. (5) Every Public Prosecutor, Additional Public Prosecutor and Special Public Prosecutor appointed by the State Government under sub-section (1), or as the case may be, sub-section (8), of section 24 to conduct cases in the High Court shall be subordinate to the Director of Prosecution. (6) Every Public Prosecutor, Additional Public Prosecutor and Special Public Prosecutor appointed by the State Government under sub-section (3), or as the case may be, sub-section (8), of section 24 to conduct cases in District Courts and every Assistant Public Prosecutor appointed under sub-section (1) of section 25 shall be subordinate to the Deputy Director of Prosecution. (7) The powers and functions of the Director of Prosecution and the Deputy Directors of Prosecution

and the areas for which each of the Deputy Directors of Prosecution have been appointed shall be such as the State Government may, by notification, specify. (8) The provisions of this section shall not apply to the Advocate General for the State while performing the functions of a Public Prosecutor. The state governments are yet to implement these provisions. Reorganization of the public prosecution system in this pattern may help a lot in preventing police torture, harassment and delays. There would be more transparency in the police-citizen relationship if the public prosecutor were an independent functionary interposed between the police and the court.

Footnote: Paper prepared for the Fourth Asian Human Rights Consultation on the Asian Charter of Rule of Law, on the theme of prosecution systems in Asia, held in Hong Kong from 17 to 21 November 2008.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Statement of Prosecution Policy and PracticeDokument51 SeitenThe Statement of Prosecution Policy and PracticePablo ChanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prefatory RevDokument10 SeitenPrefatory RevkimNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Right To Bail PDFDokument85 SeitenThe Right To Bail PDFMichelle FajardoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Confession, Judicial and Extra Judicial, AdmissibilityDokument3 SeitenConfession, Judicial and Extra Judicial, AdmissibilityamitrupaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Motion To Revoke Probation Knox CountyDokument2 SeitenMotion To Revoke Probation Knox CountyKHQA NewsNoch keine Bewertungen

- INTRODUCTIONDokument27 SeitenINTRODUCTIONsamridhi chhabraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidayatullah National Law University: Role and Function of PoliceDokument21 SeitenHidayatullah National Law University: Role and Function of PolicePankaj SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Necessary and Proper PartiesDokument4 SeitenNecessary and Proper PartiesGauri ChuttaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- I. CONTENTS (Sec. 3 and 4)Dokument7 SeitenI. CONTENTS (Sec. 3 and 4)roselleyap20Noch keine Bewertungen

- Habeas CorpusDokument67 SeitenHabeas CorpusButch AmbataliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rights of The AccusedDokument168 SeitenRights of The AccusedMrs. WanderLawstNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pre-Trial Process: Plea BargainingDokument4 SeitenPre-Trial Process: Plea BargainingFarah FarhanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Classification of Offences, Theories of PunishmentDokument14 SeitenClassification of Offences, Theories of PunishmentKanooni SalahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Misjoinder and Non Joinder of PartiesDokument8 SeitenMisjoinder and Non Joinder of PartiesShabnam Barsha0% (1)

- Plea BargainingDokument12 SeitenPlea Bargainingabdul.rani6051Noch keine Bewertungen

- List of Cases of Supreme Court, 2010Dokument31 SeitenList of Cases of Supreme Court, 2010Nagaraja ReddyNoch keine Bewertungen

- KP4. Primer 1 Building The Philippine Political Party System PDFDokument52 SeitenKP4. Primer 1 Building The Philippine Political Party System PDFNoli Sta TeresaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Using Statutory and Case Law, Discuss in Details The Principle of Relevancy. (25 Marks)Dokument7 SeitenUsing Statutory and Case Law, Discuss in Details The Principle of Relevancy. (25 Marks)Brian Abaga100% (2)

- Role of Hostile Witnesses in The Administration of Criminal JusticeDokument15 SeitenRole of Hostile Witnesses in The Administration of Criminal JusticeDeepsy FaldessaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- LLB - Principles of Criminal LawDokument80 SeitenLLB - Principles of Criminal LawHemant MishraNoch keine Bewertungen

- CorroborationDokument1 SeiteCorroborationنور منيرة مصطفىNoch keine Bewertungen

- BailDokument6 SeitenBailspife1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Awaiting TrialDokument6 SeitenAwaiting TrialLejla NizamicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sources of Criminal LawDokument7 SeitenSources of Criminal LawDavid Lemayian SalatonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Joson Case RA 9184Dokument22 SeitenJoson Case RA 9184Myra BarandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Plea BargainingDokument12 SeitenPlea BargainingHardeep SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter-Iv Right To Bail in Bailable Offence Under Section 436 Cr. P.CDokument35 SeitenChapter-Iv Right To Bail in Bailable Offence Under Section 436 Cr. P.CEfaf Ali67% (3)

- Guilt Beyond Reasonable DoubtDokument39 SeitenGuilt Beyond Reasonable Doubtjeemee0320Noch keine Bewertungen

- Second Division Cornelio V. Yagong, A.C. No. 10333 PresentDokument5 SeitenSecond Division Cornelio V. Yagong, A.C. No. 10333 PresentAlexisNoch keine Bewertungen

- HearsayDokument4 SeitenHearsayAmmirul AimanNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is The Concept of Per IncuriamDokument3 SeitenWhat Is The Concept of Per Incuriammohit kumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rejoinder PDFDokument3 SeitenRejoinder PDFARLENE DELA TORRENoch keine Bewertungen

- Forgery of PublicDokument15 SeitenForgery of PublicKripa KafleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comment On Motion To Reduce Bail-Pp V ColladoDokument2 SeitenComment On Motion To Reduce Bail-Pp V ColladoFaridEshwerC.DeticioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prac Court 2Dokument44 SeitenPrac Court 2Patrick Marz AvelinNoch keine Bewertungen

- BailDokument7 SeitenBailLim Chon HuatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Recantation: What Probative Value Would You Give To The Recantation of V?Dokument3 SeitenRecantation: What Probative Value Would You Give To The Recantation of V?Jeryl Grace FortunaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Memo of Argument (Prosecution)Dokument7 SeitenMemo of Argument (Prosecution)Tanishq AggarwalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cross ExaminationDokument4 SeitenCross ExaminationanantNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Rights MidtermsDokument12 SeitenHuman Rights MidtermsJulius ManaloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Speedy TrialDokument26 SeitenSpeedy TrialYeoj AnchetaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Republic of The Philippines Regional Trial Court BRANCH - Zamboanga CityDokument2 SeitenRepublic of The Philippines Regional Trial Court BRANCH - Zamboanga CitySaralyn Awali SuasoNoch keine Bewertungen

- VertidoDokument103 SeitenVertidolex libertadoreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Not Valid Without Lgu Permit/Clearance: Ecember, 2016 Anuary 31, 2017Dokument2 SeitenNot Valid Without Lgu Permit/Clearance: Ecember, 2016 Anuary 31, 2017Lemuel Kim100% (1)

- Malicious ProsecutionDokument1 SeiteMalicious ProsecutionPenelope NgomaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Proof Beyond Reasonable DoubtDokument6 SeitenProof Beyond Reasonable DoubtDeen MerkaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Request For InvestigationDokument3 SeitenRequest For InvestigationNational Catholic ReporterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Specific Performance of ContractsDokument58 SeitenSpecific Performance of ContractsArun Shokeen71% (7)

- Motion For New Trial 2Dokument2 SeitenMotion For New Trial 2dhunojoanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Motion For Leave of Court To File Demurrer To Evidence Scribd - Google SearchDokument2 SeitenMotion For Leave of Court To File Demurrer To Evidence Scribd - Google SearchSarah Jane-Shae O. SemblanteNoch keine Bewertungen

- 14 Chapter-4 PDFDokument61 Seiten14 Chapter-4 PDFAditya NigamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Law of Evidence Assignment 1Dokument7 SeitenLaw of Evidence Assignment 1mandlenkosiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law UniversityDokument5 SeitenDr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law UniversityFaizaanKhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 265 A. Application of The Chapter.: Plea BargainingDokument3 Seiten265 A. Application of The Chapter.: Plea BargainingSanjay MalhotraNoch keine Bewertungen

- HLAF Criminal Procedure TagalogDokument33 SeitenHLAF Criminal Procedure TagalogKristal RamosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final OrderDokument15 SeitenFinal OrderMartin Austermuhle100% (2)

- War crimes and crimes against humanity in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal CourtVon EverandWar crimes and crimes against humanity in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal CourtNoch keine Bewertungen

- Role of Public Prosecutors in Indian Judicial SystemDokument21 SeitenRole of Public Prosecutors in Indian Judicial SystemSid'Hart Mishra100% (6)

- Public Prosecution in IndiaDokument10 SeitenPublic Prosecution in IndiaSalman AghaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Public ProsecutorDokument24 SeitenPublic ProsecutorROHITGAURAVCNLU100% (1)

- Quit Claim Deed - FOCUS PROPERTY GROUP Et Alia 30jan2020Dokument4 SeitenQuit Claim Deed - FOCUS PROPERTY GROUP Et Alia 30jan2020empress_jawhara_hilal_el100% (1)

- Coa Circular No. 1989-300Dokument2 SeitenCoa Circular No. 1989-300Erick Jay InokNoch keine Bewertungen

- Danta DubamoDokument6 SeitenDanta Dubamoermiasgensa8Noch keine Bewertungen

- Dela Cruz vs. Andres, 522 SCRA 585, April 27, 2007Dokument7 SeitenDela Cruz vs. Andres, 522 SCRA 585, April 27, 2007TNVTRLNoch keine Bewertungen

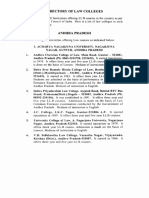

- Andhra Pradesh - Law ColleageDokument6 SeitenAndhra Pradesh - Law ColleageSreenivasareddy KonduriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Right To Work IndiaDokument5 SeitenRight To Work IndiagambitsaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cambridge Ordinary Level: Cambridge Assessment International EducationDokument8 SeitenCambridge Ordinary Level: Cambridge Assessment International Educationwaiezul73Noch keine Bewertungen

- Final ResondentDokument42 SeitenFinal Resondentsakshi vermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Constitution of PTAFOADokument15 SeitenConstitution of PTAFOAS MNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pimentel V Executive Secretary G.R. No. 158088Dokument3 SeitenPimentel V Executive Secretary G.R. No. 158088KYLE DAVIDNoch keine Bewertungen

- Factors Affecting The Effective Use of Foreign Aid by International Ngos, in SomalilandDokument17 SeitenFactors Affecting The Effective Use of Foreign Aid by International Ngos, in SomalilandYousuf abdirahman100% (2)

- Accredite D Medical Clinic Name Clinic Address Clinic'S Contact NumberDokument48 SeitenAccredite D Medical Clinic Name Clinic Address Clinic'S Contact NumberCess SexyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Republic v. Fernandez - CaseDokument2 SeitenRepublic v. Fernandez - CaseRobehgene Atud-JavinarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Commissioners For Oaths Adv ActDokument7 SeitenCommissioners For Oaths Adv ActmuhumuzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CO - Monitoring MC2006 003 MC186 6 11 2018 1 1 5Dokument5 SeitenCO - Monitoring MC2006 003 MC186 6 11 2018 1 1 5richard icalaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Full Text of "John Birch Society": See Other FormatsDokument301 SeitenFull Text of "John Birch Society": See Other FormatsIfix AnythingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hood, (1991) A Public Management For All SeasonsDokument18 SeitenHood, (1991) A Public Management For All SeasonsTan Zi Hao0% (1)

- Attachment and Sale of Property Under Civil Procedure CodeDokument17 SeitenAttachment and Sale of Property Under Civil Procedure CodeRajesh BazadNoch keine Bewertungen

- San Juan V Civil Service CommissionDokument3 SeitenSan Juan V Civil Service CommissionMarefel AnoraNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Land in Conflict On Myanmar's Western FrontierDokument160 SeitenA Land in Conflict On Myanmar's Western FrontierInformer100% (1)

- Central Vigilance Commission PDFDokument2 SeitenCentral Vigilance Commission PDFKs DilipNoch keine Bewertungen

- Agrarian ReformDokument36 SeitenAgrarian ReformSarah Buhulon83% (6)

- Legaspi Vs CSCDokument2 SeitenLegaspi Vs CSCcyhaaangelaaa100% (1)

- The International Tribunal For The Law of The Sea (ITLOS) - InnoDokument70 SeitenThe International Tribunal For The Law of The Sea (ITLOS) - InnoNada AmiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- 14.characteristics and Scope of Application of Criminal LawDokument3 Seiten14.characteristics and Scope of Application of Criminal Lawcertiorari1963% (8)

- Jeeshan Jaanu V State of UPDokument38 SeitenJeeshan Jaanu V State of UPWorkaholicNoch keine Bewertungen

- The War Powers Act of 1973Dokument7 SeitenThe War Powers Act of 1973ruslan3338458Noch keine Bewertungen

- British Monarchy Lesson PlanDokument12 SeitenBritish Monarchy Lesson PlanPopa NadiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Police Patrol Opn SyllabusDokument3 SeitenPolice Patrol Opn SyllabusDraque TorresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Confidential Non-Disclosure AgreementDokument1 SeiteConfidential Non-Disclosure AgreementTammie WalkerNoch keine Bewertungen