Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

King Henry

Hochgeladen von

Maxie PacadaCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

King Henry

Hochgeladen von

Maxie PacadaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The early English Reformation craeated an Anglican Church even more politically oriented than Lutheranism.

The leader of the Reformation in England was not a dissenting priest but rather the reigning monarch, Henry VIII (1504-1547). His primary motive was securing his Tudor dynasty, although access to the wealth of the English Catholic Church was also a major consideration. Protestant ideas concerning theology and ritual did not much interest him, as was demonstrated by his persecution of dissident Protestants as well as Catholics. While Henry lived, the English Church reflected his will, but after his death, the country was nearly torn apart by corrupt politics and religious fanaticism. The Annulment Issue Henry's immediate problem in the 1520s was the lack of a male heir. After eighteen years of marriage, he had only a sickly daughter and an illegitimate son. His queen, Catherine of Aragon (1485-1536), after four earlier pregnancies, gave birth to a stillborn son in 1518, and by 1527, when she was 42, Henry had concluded that she would have no more children. His only hope for the future of his dynasty seemed to be a new marriage with another queen. This, of course, would require an annulment of his marriage to Catherine. In 1527, he appealed to the pope, asking for the annulment. Normally, the request would probably have been granted; the situation, however, was not normal. Catherine had first been the wife of Henry's deceased brother Arthur. Her marriage to Henry had required a papal dispensation, based on her oath that the first marriage had never been consummated. Now Henry professed concern for his soul, tainted by living in sin with Catherine for eighteen years. He also claimed that he was being punished, citing a passage in the Book of Leviticus, which predicted childlessness for the man who married his dead brother's wife. The pope was sympathetic and certainly aware of an obligation to Henry, who for his verbal attacks against Luther had been named "Defender of the Faith" by a grateful earlier pontiff; but granting the annulment would have been admission of papal error, perhaps even corruption, in issuing the dispensation. Added to the Lutheran problem, this would have been doubly damaging to the papacy. A more formidable problem for Henry was Catherine. She was a cultured Spanish woman a respected consort, and a devoted wife, who had had successfully conducted a war against Scotland while Henry was campaigning in France. Henry recognized her strong character in their daughter, Mary, whom he appointed Princess of Wales and heir apparent, in the absence of a prince. As late as the mid-1520s, he sought Catherine's counsel and her companionship. Henry soon learned that Catherine would never accept an annulment, and he was afraid she might lead rebellion against him. As the aunt of Charles v, whose armies occupied Rome in 1527, she also exerted considerable pressure on the

pope. Despite these difficulties, Henry could hope for success in his appeal to the pope. Any conflict with Rome was in accord with national pride, often expressed in traditional resentment against Roman domination. Late medieval English kings had challenged the popes over Church appointments and revenues. More than a century and a half before Luther, an Oxford professor named John Wycliffe had denounced the false claims of popes and bishops. In more recent times, English Christian humanists, such as Sir Thomas More, had criticized the artificialities of Catholic worship. Thus when the pope delayed making a decision, Henry was relatively secure in his support at home. The English Reformation And Reaction During the three years after 1531, when Catherine saw him for the last time, Henry took control of affairs. Lodging his daughter and his banished wife in separate castles, he forbade them from seeing each other. He also intimidated the clergy into proclaiming him head of the English Church "as far as the law of Christ allows," extracted from Parliament the authority to appoint bishops, and designated his willing tool, Thomas Cranmer (1489-1556), as Archbishop of Canterbury. In 1533, Cranmer pronounced Henry's marriage to Catherine invalid, at the same time legalizing the king's union with Ann Boleyn, a lady of the court who was already carrying his unborn child. Parliament also ended all payments of revenues to Rome. Now, having little choice, the pope excommunicated Henry, making the breach official on both sides. Amid a marked anti-Catholic campaign in the 1530s, Henry secured the Anglican establishment, which became an engine for furthering royal policies, with the king's henchmen controlling every function, from the building of chapels to the wording of the liturgy. Former church revenues, including more than 40,000 a year from religious fees alone, poured into the royal treasury. In 1539, Parliament completed its seizure of monastery lands, selling some for revenue and dispensing others to secure the loyalties of crown supporters. Meanwhile, Catholics suffered. Dispossessed nuns, unlike monks and priests, could find no place in the new church and were often reduced to despair. One, the famous "holy maid of Kent," who dared to rebuke the king publicly, was executed, as were other Catholic dissidents, including the king's former chancellor, Sir Thomas More, and the saintly Bishop Fisher of Rochester. Henry even forced his daughter, Mary, to accept him as head of the church and admit the illegality of her parents' marriage. The new English Church, however, brought little change in doctrine or ritual. The "Six Articles," Parliament's declaration of the new creed and ceremonies in 1539, reaffirmed most Catholic theology, except papal supremacy. Henry, in his later years after the execution of Anne in 1536, grew

increasingly suspicious of popular Protestantism, which was spreading into England and Scotland from the Continent. He refused to legalize clerical marriage, which caused great hardships among many Anglican clergymen, including some bishops, and their wives. Henry's sixth wife, the former Catherine Parr, who was sympathetic to the reformers, narrowly escaped the king's displeasure by humbly appealing to his vanity. Others were not so lucky. Perhaps the most notable among many Protestant martyrs was Anne Askew, a woman of Lincolnshire, who was tried before a church court for heresy and so confounded her judges that she became a legend. She was nevertheless burned in 1546, a year before Henry died.

UNIVERSITY OF PERPETUAL HELP SYSTEM-ISABELA CAMPUS COLLEGE OF NURSING

MANANTE I, CAUAYAN, ISABELA

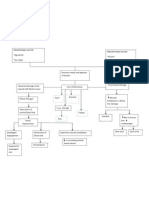

ADVOCACY OF KING HENRY VIII

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Miracles SummaryDokument128 SeitenMiracles SummaryJorge SandyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Protestant Reformation Sparked by Luther's 95 ThesesDokument74 SeitenProtestant Reformation Sparked by Luther's 95 ThesesFobe Lpt NudaloNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Jesus Prayer Meditation, by Mary KretzmannDokument12 SeitenJesus Prayer Meditation, by Mary KretzmannMary Kretzmann100% (4)

- Worship PDFDokument56 SeitenWorship PDFIsrael Fred LigmonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Blessed MatronushkaDokument3 SeitenBlessed MatronushkaHristofor HristoforusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anth 72 Saturday 1st EditionDokument144 SeitenAnth 72 Saturday 1st EditionJohn Arunas ZizysNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hierarchy AngelsDokument4 SeitenHierarchy AngelsMegan Nate100% (1)

- Agobard of Lyons: Early Medieval Bishop Known for Opposing SuperstitionsDokument28 SeitenAgobard of Lyons: Early Medieval Bishop Known for Opposing SuperstitionsMarius AndroneNoch keine Bewertungen

- History of DenmarkDokument21 SeitenHistory of DenmarkSighninNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Biblical Philosophy of MinistryDokument11 SeitenA Biblical Philosophy of MinistryDavid Salazar100% (3)

- Bach Seufzer Tranen PDFDokument71 SeitenBach Seufzer Tranen PDFFederica RajaNoch keine Bewertungen

- La Bible Traduite en Francais Con Tempo RainDokument297 SeitenLa Bible Traduite en Francais Con Tempo RainAlainzhuNoch keine Bewertungen

- PDFDokument1 SeitePDFMaxie PacadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Constipation IntroductionDokument3 SeitenConstipation IntroductionMaxie PacadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is Anemia?: Iron Vitamin B12 Folic AcidDokument8 SeitenWhat Is Anemia?: Iron Vitamin B12 Folic AcidMaxie PacadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- NeurotransmittersDokument2 SeitenNeurotransmittersMaxie PacadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conque R The Muslim Port of GoaDokument84 SeitenConque R The Muslim Port of GoaMaxie PacadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Patho of Liver Cirrhosis 22222 (Repaired)Dokument2 SeitenPatho of Liver Cirrhosis 22222 (Repaired)Maxie PacadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Discharge PlanDokument1 SeiteDischarge PlanMaxie PacadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Documents of Vatican IIDokument12 SeitenDocuments of Vatican IIZandro Louie OrañoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Portuguese of CalcuttaDokument5 SeitenThe Portuguese of CalcuttaSujit DasguptaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Joint Base Military Relocation Yellow PagesDokument60 SeitenJoint Base Military Relocation Yellow PagesswtxpubNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Chalice: The Pastor's CornerDokument14 SeitenThe Chalice: The Pastor's CornerSt. Francis' Episcopal Church - EurekaNoch keine Bewertungen

- (No Audio) El Shaddai Diocesan Mass Line Up May 28, 2016Dokument68 Seiten(No Audio) El Shaddai Diocesan Mass Line Up May 28, 2016Emmanuel RapadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hegel and The AlphabetDokument11 SeitenHegel and The AlphabetEdu Beta100% (1)

- List of Officers and Churches for Adventist Gulf RegionDokument3 SeitenList of Officers and Churches for Adventist Gulf RegionMoses LevNoch keine Bewertungen

- Songs For LentDokument56 SeitenSongs For LentGovel EzraNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Impact of African Caribbean Settlers On SDA ChurchDokument334 SeitenThe Impact of African Caribbean Settlers On SDA Churchtom100% (1)

- Camomot BookDokument33 SeitenCamomot Bookjose kenneth greenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ancop - MolaveDokument3 SeitenAncop - MolaveRalph Christer MaderazoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Narratives of The Spirit: Recovering A Medieval Resource : - CTSA PROCEEDINGS 51 (1996) : 45-90Dokument46 SeitenNarratives of The Spirit: Recovering A Medieval Resource : - CTSA PROCEEDINGS 51 (1996) : 45-90Melisa MackNoch keine Bewertungen

- IMSLP96616 PMLP54405 214711 Telemann 12 Fantasias Sheet MusicDokument2 SeitenIMSLP96616 PMLP54405 214711 Telemann 12 Fantasias Sheet MusicUlyssesm90Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Nine Day Novena To ST JudeDokument2 SeitenThe Nine Day Novena To ST JudeGerardo Luis DimaguilaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Food Pantries in The BXDokument8 SeitenFood Pantries in The BXXernna TheEntrepreneur NievesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reviving Church Art PatronageDokument4 SeitenReviving Church Art PatronageEduardo FigueroaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Riverview Annual Report 2012Dokument4 SeitenRiverview Annual Report 2012api-198623878Noch keine Bewertungen

- Todd Bentley Emma o Goddess of The Underworld.1Dokument17 SeitenTodd Bentley Emma o Goddess of The Underworld.1Pat Ruth HollidayNoch keine Bewertungen