Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Heart Murmurs and Congenital Heart Disease in Pediatric Patients

Hochgeladen von

nicdeepCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Heart Murmurs and Congenital Heart Disease in Pediatric Patients

Hochgeladen von

nicdeepCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

1

Heart Murmurs and Congenital Heart Disease in Pediatric Patients

Heather M. Taylor, MD

You Hear a Heart MurmurNow What? Step 1 Take a Good History o Prenatal history Teratogens Lithium is associated with Ebstein anomaly (abnormality of the tricuspid valve leading to tricuspid insufficiency and RV outflow tract obstruction). Congenital heart disease is a component of fetal alcohol syndrome (VSD, ASD). Maternal illnesses Infants of diabetic mothers have an increased risk of congenital heart disease (transient hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, tetralogy of Fallot, truncus arteriosus). Overt and occult maternal collagen vascular disease is associated with fetal complete heart block. TORCH infections Rubella and CMV congenital infections are associated with heart defects in fetuses. Prenatal US findings Abnormalities may have been diagnosed on prenatal ultrasound. o Family history Congenital heart disease Epidemiologic studies have suggested a multifactorial form of inheritance for a majority of cardiac defects, with recurrence risks of 1-4%. Sudden cardiac death in persons <55 Associated with Marfan syndrome and hypertrophic subaortic cardiomyopathy among other etiologies. o Previous history of a murmur Ask the parents if anyone has ever told them before that they heard a heart murmur and what was said about it at that time. o Past medical history Multiple genetic syndromes have associated cardiac defects (Trisomy 21, Turner, Noonan, William, Marfan, DiGeorge, etc). o Symptoms Many children are asymptomatic because the lesion does not result in hemodynamic alterations or because their myocardium can adapt. A comparable lesion in an adult may produce symptoms because of coexistent coronary arterial disease or myocardial fibrosis. If they are symptomatic, associated symptoms can be classified by age.

2 Infants o o o o

Feeding intolerance Failure to thrive Increased respiratory infections Cyanosis (usually only seen if the systemic arterial oxygen saturation is less than 88%) o Rapid breathing o Sweating (especially with feeding, exertion) Older children o Chest pain (especially with exercise) o Syncope or near-syncope o Dyspnea o Fatigue o Palpitations o Exercise intolerance Step 2 Pay Attention to the Vital Signs o Growth Charts Congenital heart disease is on the DDX of failure to thrive o Blood Pressure (should be taken in both arms and at least 1 leg) Coarctation of the aorta is associated with a systolic BP 20mm Hg or more lower in the legs than in the right arm (Note: if the patient has an open PDA, you may not see this blood pressure difference.) Pulse Pressure (the difference of systolic and diastolic pressures) Narrow pulse pressure (<25mmHg) is associated with: severe aortic stenosis, pericardial effusion/tamponade, pericarditis, significant tachycardia Wide pulse pressure (>40mmHg) is associated with: conditions with increased cardiac output (anemia, thyrotoxicosis) or with abnormal runoff of blood from the aorta during diastole (patent ductus arteriosus or PDA, aortic insufficiency). o Pulse Coarctation is associated with difficult to palpate femoral pulses. PDA and aortic insufficiency are associated with bounding pulses. Tachycardia may be a neonates only way to increase cardiac output with their limited ability to increase contractility or preload or decrease afterload. o Respiratory rate and effort Looking for signs of congestive heart failure Tachypnea o Oxygen saturation To detect subclinical cyanosis Can help differentiate cyanosis due to intracardiac shunting from that due to pulmonary pathology Differential oxygen saturation

3 Higher O2 sat in upper extremities vs. lower extremities seen with right-to-left shunt through open ductus arteriosus

Step 3 - Exam o General appearance Looking for syndromic features or signs of distress. o Palpation of precordium Thrills are coarse low frequency vibrations occurring with loud murmurs and located in the same areas as the maximal intensity of the murmur. Increased precordial activity (hyperdynamic precordium) Commonly felt in patients with increased right or left ventricular stroke volume. Locate the point of maximal impulse (PMI) should be ~left mid-clavicular line. o Auscultation High-pitched murmurs and S1, S2 are heard best with the diaphragm of the stethoscope. Low-pitched murmurs and S3 are heard best with the bell. Listen with the patient sitting, reclining, and standing. o Heart sounds S1 Associated with the closure of the mitral and tricuspid valves. Can be timed by simultaneously feeling the carotid or femoral pulse while listening to the heart; the sound heard when the pulse is felt is S1. Will be loud in patients with fever, anemia, mitral stenosis, systemic hypertension. The individual components are usually indistinguishable, so the 1st heart sound is single. (Exception is complete right bundle branch block where tricuspid valve closure is delayed.) S2 Associated with the closure of the aortic and pulmonic valves. There is a normal physiologic split of S2 heard on inspiration; it becomes single on expiration. o During inspiration, there is a decrease in intrathoracic pressure that permits an increase in venous return to the right atrium. This increased blood in the right atrium prolongs right ventricular systole and delays pulmonic valve closing. Abnormalities in S2 o Wide split S2 The normal physiologic split S2 can be accentuated by conditions that cause abnormal delay in pulmonic valve closure. Increased volume in the RV compared with the left ventricle (ASD, VSD)

4 o Chronic right ventricular outflow tract obstruction (pulmonary stenosis) Delayed right ventricular activation (complete RBBB)

Single S2 Usually indicates that one of the semilunar valves is atretic or severely stenotic. Also single in truncus arteriosus or whenever the pulmonary pressure exists at systemic levels. o Loud S2 Usually indicative of pulmonary hypertension, which can be seen in patients with large left-to-right shunts. Ejections sounds or clicks High frequency clicking sounds. Produced when blood is ejected from the right or left ventricle either through a stenotic valve or into a dilated chamber. Heart Murmurs Location Valve area where the murmur is heard the best o Upper right sternal border (2nd intercostal space to right of sternum; aortic valve) o Upper left sternal border (2nd intercostal space to left of sternum; pulmonic valve) o Lower left sternal border (tricuspid valve and ventricular septum) o Apex (mitral valve)

Loudness (intensity) I heard after the listener tunes in II Heard immediately, but faint III Loud, but without a thrill IV Loud with a thrill V Loud with a thrill and audible with the stethoscope tilted on the chest VI Loud with a thrill and audible with the stethoscope off the chest Quality Blowing, harsh, soft, musical, vibratory Timing Systolic (between S1 and S2) or diastolic (between S2 and S1) Radiation

5 Murmurs originating from the aortic outflow area radiate toward the neck and into the carotid arteries. Murmurs originating from the pulmonic outflow area are transmitted to the left upper back. Mitral murmurs are transmitted toward the cardiac apex and the left axilla. Systolic murmurs Possible causes: Blood flow across an outflow tract (pulmonic stenosis, aortic stenosis, hypertrophic subaortic cardiomyopathy) VSD, ASD Atrioventricular valve regurgitation (mitral or tricuspid insufficiency) PDA Coarctation of the aorta Types of systolic murmurs: Holosystolic murmurs o VSD, mitral insufficiency, tricuspid insufficiency, PDA Systolic ejection murmurs o ASD, VSD, aortic stenosis, pulmonary stenosis, hypertrophic subaortic cardiomyopathy, coarctation of the aorta Diastolic murmurs Possible causes: Aortic or pulmonic valve insufficiency Mitral or tricuspid valve stenosis Normal functional (innocent) murmurs in children Characteristics: Normal S1, S2 Normal heart size Lack of significant cardiac symptoms Grade III/VI or less Located in a small, well-defined area Systolic or continuous Stills murmur Thought to originate from turbulent outflow from narrow areas of left ventricular output. Soft, low-pitched, vibratory systolic ejection murmur that is heard between the mid-to-lower sternal border and the apex with limited radiation. Heard best in the supine position and decreases in intensity when the patient stands. Heard in 75-85% of school-aged children. Differential diagnosis includes VSD, LV outflow tract obstruction these pathologic murmurs are usually of higher intensity and do not decrease with standing.

6 Pulmonary flow murmur Also known as a pulmonary ejection murmur. Thought to originate from turbulent outflow from narrow areas of the right ventricular output. Soft, low to medium-pitched systolic ejection murmur heard in the left upper sternal border. Diminishes in intensity with standing. Found in children, adolescents, and young adults. Most common between the ages of 8 and 14. Differential diagnosis includes ASD and pulmonic stenosis these pathologic murmurs will have associated abnormalities in S2 (wide or fixed split S2) and an ejection click (pulmonic stenosis). Peripheral pulmonary stenosis (PPS) Also called physiologic branch pulmonary artery stenosis. Originates from relative hypoplasia of right and left pulmonary artery branches. Heard in most premature neonates and in many term infants. Soft, medium to high-pitched systolic flow murmur best heard in the axillae and back (also heard at the left upper sternal border). Should not persist after 6 months of age. Differential diagnosis includes pulmonic stenosis (associated S2 abnormalities and ejection click). Venous hum Caused by the flow of venous blood from the head and neck into the thorax. Continuous murmur heard best in the right infraclavicular area. Louder in diastole. Heard best with the patient sitting; should disappear when the child reclines, when light pressure is applied over the jugular vein, or when the childs head is turned away from the side of the murmur. Heard in children ages 3-6. Other important exam findings related to evaluation of cardiac pathology Hepatomegaly (seen with right heart failure) Clubbing (seen with chronic cyanosis)

So When Do You Worry? Red Flag on History o Risk factor, symptomatic Red Flag in Vital Signs Heart Murmur that is: o Loud

7 o o o o Holosystolic, late systolic, or diastolic Does not decrease in intensity with standing Associated with abnormalities in S1 or S2 or ejection click Associated with other exam abnormalities (displaced PMI, pulse differential, hyperdynamic precordium, HSM, clubbing, respiratory distress)

Congenital Heart Lesions to Know Ventricular Septal Defect o The most common congenital heart defect, making up 25-30% of cases of congenital heart lesions in term newborns. o Usually occur as isolated abnormalities, but can occur with other congenital cardiac abnormalities. o At birth, a majority occur in the muscular septum and usually close spontaneously before age 1. After 1 year, the majority of VSDs occur in the membranous septum. o Symptoms Most symptoms with large VSDs and large shunts will occur in term infants 4-8 weeks of age and will consist of symptoms of volume overload and heart failure. o Exam Findings Will present with a harsh, holosystolic murmur heard best at the lower sternal border with radiation through the precordium. If pulmonary hypertension develops (because of a large left-to-right shunt), the pulmonic component of the 2nd heart sound will increase in intensity and there will be evidence of cardiomegaly and increased proximal pulmonary vasculature markings on chest xray. Atrial Septal Defect o Can be further classified as ostium secundum and ostium primum defects. Ostium secundum ASD Most common form of ASD. Located in the mid-septum. Normally isolated lesions that can are usually small. Symptoms o Most are asymptomatic and it is very unusual for these patients to present with cardiac failure; pulmonary hypertension can occur but it is usually not until 20-30 years of age. o Other symptoms seen in adults include arrhythmias (usually atrial fibrillation/flutter) and embolic strokes. Exam findings o Long, systolic crescendo-decrescendo murmur heard best at the upper left sternal border.

8 The murmur is not due to the ASD, but the increased flow across the right ventricular outflow tract and pulmonic valve. o Wide, fixed, split S2 Treatment o Usually closed surgically within 5 years after diagnosis to prevent later complications in adulthood. o These patients do not need endocarditis prophylaxis. Ostium primum ASD Located in the lower portion of the atrial septum in the region of the mitral and tricuspid valve rings. Is a form of AV canal defect, often called a partial AV canal defect. Usually a very large defect with the anterior mitral valve leaflet displaced as a result. Symptoms o If a large shunt is present, these patients can develop pulmonary hypertension with heart failure. Exam findings o Right ventricular outflow murmur, a tricuspid valve mid-diastolic flow murmur, and a widely spit S2. Treatment o These patients need endocarditis prophylaxis. o Surgically corrected early in childhood. Coarctation of the aorta o Develops from a defect in the media of the aorta that causes a posterior infolding of the vessel. o If the obstruction is severe, it can present as congestive heart failure in newborns (these patients will look a lot like the infants with severe aortic stenosis with diminished pulses and shock-like appearance). o It usually presents in otherwise asymptomatic older children and young adults during a workup of hypertension or a murmur. o Exam findings include a systolic murmur heard best in the back (at the left scapular angle), hypertension in upper extremities, and absent or difficult to palpate femoral pulses. Aortic Valve Stenosis o Almost all (>85%) cases of congenital stenotic aortic valves are bicuspid. o Symptoms The infant with severe aortic stenosis will present in the 1st week of life with poor perfusion and diminished peripheral pulses. In milder cases of aortic stenosis, the patients are usually asymptomatic initially (will compensate by developing left ventricular hypertrophy to maintain cardiac output), but can become symptomatic as the stenosis progresses. o Exam findings Crescendo-decrescendo, harsh systolic murmur heard best at the right upper sternal border, often with an early ejection click.

9 Narrow pulse pressure Can have paradoxical splitting of the 2nd heart sound (you hear the split in S2 during expiration instead of inspiration). o Treatment These patients need endocarditis prophylaxis. Balloon valvuloplasty is the treatment of choice in children; ~40% need repeat treatment within 10 years for restenosis. Surgical treatment includes mechanical valve replacement and the Ross procedure. In the Ross procedure, the pulmonary valve ring is moved into the aortic valve area and a homograft is used to replace the pulmonary valve. Endocardial Cushion Defect or Complete AV Canal Defect o Involves a defect in the development of the endocardial cushions, resulting in a large hole communicating between the atria and ventricles, as well as malformation of the tricuspid and mitral valves. The anterior and posterior segments of each leaflet join each other through the defect resulting in a common AV valve (see picture).

o o o o

The overall result is a large left-to right shunt and valve regurgitation leading to volume overload and congestive heart failure. This is the most common heart defect in Trisomy 21. Symptoms These infants most often present with heart failure by 2 months of age. Exam findings Characteristic murmur of a VSD, mid-diastolic murmur of increased diastolic flow across the AV valve, and often regurgitant murmurs of the tricuspid and mitral valves.

10 CXR will show cardiomegaly. o Treatment Includes medical management of congestive heart failure and surgical correction of the lesion in the 1st 6-12 months. Idiopathic Hypertrophic Subaortic Stenosis (IHSS) o Inherited as an autosomal dominant disorder with variable expression. o Characterized by asymmetric hypertrophy of the left ventricular outflow tract. o Symptoms This is the most common cause of sudden death in athletes; these patients most commonly die of arrhythmias. o Exam findings Crescendo-decrescendo systolic murmur heard best at the middle left to right upper sternal border The murmur gets louder with Valsalva or standing; it decreases with squatting (the opposite will occur with the murmur of aortic stenosis). CXR and ECG will show LVH. o Treatment Medical therapy includes beta blockers and calcium channel blockers. Surgical treatment involves the removal of the hypertrophied cardiac muscle. Some patients require implantable defibrillators. Pulmonic stenosis/atresia o 2nd most common congenital heart defect (VSD is the most common). o The overall formation and size of the right ventricle and tricuspid valve are related to the time in gestation in which pulmonic stenosis occurs. If it is early, venous return is likely to be diverted across the foramen ovale and the RV and tricuspid valve are going to be small. If the stenosis occurs later in gestation, RV formation is likely to be normal. o The severity of the symptoms depends on the extent of the stenosis and the degree to which the RV and tricuspid valve development have been affected. Infants with severe pulmonic stenosis will present in early infancy with severe cyanosis and cardiac collapse as the ductus arteriosus closes. Most affected children are asymptomatic and are picked up only because of a murmur. o Exam findings include a systolic ejection click along the left sternum, followed by a crescendodecrescendo systolic murmur heard best at the left upper sternal border which radiates to below the left clavicle and to the back. There is also a wide, split S2 or a single S2. Tetralogy of Fallot o Most common cyanotic heart lesion in children with congenital heart disease who have survived untreated beyond infancy. o Composed of right ventricular outflow tract obstruction, VSD, an overriding aorta, and right ventricular hypertrophy.

11 Symptoms include cyanosis (the severity of which depends of the degree of the right ventricular outflow tract obstruction and the resulting right-to-left shunt across the VSD) and Tet spells. Tet spells occur when there is an acute reduction in pulmonary blood flow, a drop in systemic afterload, and a worsened right-to-left shunt. Watch for on tests the child who squats after exertion (the squatting causes increased arterial oxygen saturation due to increased systemic arterial resistance which leads to increased pulmonary blood flow). o Exam findings include a systolic murmur due to the VSD and the right ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Transposition of the great arteries o Complete transposition of the great arteries is the most common cardiac cause of cyanosis in the newborn during the 1st few days of life. o In this defect, the systemic venous return goes into the right atrium, the right ventricle, and then out the transposed aorta. The oxygen-rich pulmonary venous return goes into the left atrium, the left ventricle, and then is ejected back into the lungs via the transposed pulmonary artery. So, these patients are dependent on a connection between the right and left circulations for survival. The ductus arteriosus is that connection early on, but doesnt help very much and these infants are usually cyanotic at birth with worsening cyanosis over the 1st few hours. o Exam findings include a single, loud S2 (because the aorta is right under the sternum). Total anomalous pulmonary venous return o In this defect, the pulmonary veins connect either to the right atrium or to veins draining into the right atrium. Blood gets to left side of heart through patent foramen ovale or ASD o There are 3 main types of anatomic connections that occur: Supracardiac (30%) Pulmonary venous return via a left vertical trunk into the left innominate vein, and then into the superior vena cava. Cardiac (30-40%) Pulmonary veins connect directly to the right atrium or the coronary sinus. Infradiaphragmatic (20-25%) Pulmonary veins will go below the diaphragm, connect with the ductus venosus, and then into the inferior vena cava. These patients are most likely to have severe obstruction to pulmonary venous return. o Those with severe obstruction to pulmonary venous return will present early on with symptoms of pulmonary edema and cyanosis. Those without pulmonary venous return obstruction will have minimal cyanosis initially. o These patients do not have murmurs. o

12 Truncus arteriosus o Occurs when a single arterial trunk comes off from the ventricular chambers and then supplies the coronary, pulmonary, and systemic circulations. The trunk overrides a VSD. o A large number of patients with truncus arteriosus have an associated chromosomal abnormality (such as partial deletion of chromosome 22 DiGeorge syndrome). o The patients often have only minimal cyanosis because of increased pulmonary blood flow. o They typically present in the first few weeks to months of life with left heart failure and failure to thrive. o Exam findings include mild cyanosis, a single S2, and bounding peripheral pulses. Hypoplastic left heart o Involves underdevelopment of the left side of the heart, with resulting dilation and hypertrophy of the right side of the heart. o The right side of the heart supports both the systemic and pulmonary circulations using a PDA. o Accounts for 25% of all cardiac deaths in the 1st year of life. o These patients will present with cyanosis, poor perfusion, and congestive heart failure as the ductus arteriosus closes. o Exam findings include a hyperdynamic precordium with diminished peripheral pulses. Tricuspid Atresia o Absence of the tricuspid opening; as a result, the only way of getting blood from the right atrium to the rest of the circulation is via a foramen ovale. Results in hypoplasia of the right ventricle due to decreased blood flow. o Usually occurs in association with a VSD, which allows pulmonary blood flow across the VSD to the hypoplastic right ventricle, and into the pulmonary artery. o Cyanosis appears within hours to days after birth, when the ductus arteriosus begins to close. o Exam findings include a murmur characteristic of the VSD.

Presentation of Congenital Heart Disease in Infants Typically presents in 1 of 4 ways: o Asymptomatic newborn who has murmur Several of the CHD lesions will often not cause symptoms in initial newborn period including: Non-critical aortic and pulmonic stenosis Pink Tetralogy of Fallot Small to medium VSD ASD Mild to moderate Coarctation of the aorta o Cyanosis 5 Ts (plus the Hplus the PA)

13 Thanks to the ductus arteriosus and foramen ovalethese patients might have minimal to no cyanosis initially Exceptions: Transposition of the great arteries Pulmonic valve atresia (esp with intact ventricular septum) Remember to think cyanotic heart disease in newborn with persistent, peaceful tachypnea Progressive heart failure Seen most commonly with: Large VSD Endocardial cushion defects Large persistently patent Ductus Arteriosus These patients typically asymptomatic at birth, but develop symptoms as pulmonary vascular resistance falls. Symptoms: tachypnea, sweating, difficulty feeding, FTT, gallop rhythm, hepatomegaly Shock or catastrophic heart failure Seen most commonly with: Critical coarctation of the aorta Critical aortic valve stenosis Hypoplastic left heart syndrome Only clues in newborn nursery may be single and loud S2, marked increase in right ventricular activity on precordial palpation, or minimally abnormal postductal pulse ox (in HLHS) May not have pulse differential yet because of large, open ductus arteriosus Clinical presentation can mimic sepsis: Tachypnea Mottled gray skin Poor perfusion Clues that its cardiac vs septic shock: Gallop rhythm Marked hepatomegaly or cardiomegaly Profound metabolic acidosis (pH of 7.0 or less)

Helpful Websites http://www.med.ucla.edu/wilkes/ http://www.cardiologysite.com/

14 References Johnson, Jr., Walter H., and James H. Moller. Pediatric Cardiology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001. 1-28, 145-53. Benavidez, Oscar, Allan Goldblatt, and Leonard S. Lilly. Heart Sounds and Murmurs. Pathophysiology of Heart Disease. 2nd ed. Ed. Leonard S. Lilly. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1998. 25-38. Erickson, Barbara. Heart Sounds and Murmurs: A Practical Guide. 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby-Year Book, Inc., 1991. McConnell, Michael M., Samuel B. Adkins III, and David W. Hannon. Heart Murmurs in Pediatric Patients: When Do You Refer? American Family Physician 1999 Aug; 60(2): 558-65. Rosenthal, A. How to distinguish between innocent and pathologic murmurs in childhood. Pediatric Clinics of North America 1984; 31: 1229-40. Pelech, AN. The cardiac murmur: when to refer? Pediatric Clinics of North America 1998; 45: 107-22. Silberback M, Hannon D. Presentation of Congenital Heart Disease in the Neonate and Young Infant. Pediatrics in Review 2007; 28; 123-131. Menashe, Victor. Heart Murmurs. Pediatrics in Review 2007; 28; e19-e22.

Edited 12/7/11

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Print - Ectopic Pregnancy - 10min TalkDokument2 SeitenPrint - Ectopic Pregnancy - 10min TalknicdeepNoch keine Bewertungen

- BRCA1/BRCA2 Genes: Account For 10%Dokument2 SeitenBRCA1/BRCA2 Genes: Account For 10%nicdeepNoch keine Bewertungen

- Overview of Pediatric GeneticsDokument12 SeitenOverview of Pediatric Geneticsnicdeep100% (1)

- LSU Peds ReviewDokument27 SeitenLSU Peds Reviewnicdeep100% (2)

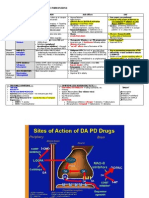

- Pharmacologic TX For Idiopathic Parkinsons: Strategy Class / Drug MOA Side Effects USEDokument2 SeitenPharmacologic TX For Idiopathic Parkinsons: Strategy Class / Drug MOA Side Effects USEnicdeepNoch keine Bewertungen

- PBL - Myasthenia GravisDokument2 SeitenPBL - Myasthenia Gravisnicdeep100% (1)

- Neurocutanous SyndromesDokument3 SeitenNeurocutanous SyndromesnicdeepNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Chapter 5: Electrolyte and Acid - Base Disorders in MalignancyDokument7 SeitenChapter 5: Electrolyte and Acid - Base Disorders in MalignancyPratita Jati PermatasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- DM - MCH Admission 2024-UCEWorldGrowMoreDokument7 SeitenDM - MCH Admission 2024-UCEWorldGrowMoreUCSWorldGrowMoreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Neurophilosophy and The Healthy MindDokument6 SeitenNeurophilosophy and The Healthy MindNortonMentalHealthNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anti UlcerDokument14 SeitenAnti UlcerUday SriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Please Admit To Room of Choice Under The Service of DRDokument2 SeitenPlease Admit To Room of Choice Under The Service of DRDave AnchetaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diagnosis Dan Manajemen BVVPDokument33 SeitenDiagnosis Dan Manajemen BVVPHeppyMeiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Midwifery Evidence Based Practice March 2013 PDFDokument11 SeitenMidwifery Evidence Based Practice March 2013 PDFFthrahmawatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maternal Child Nursing PDFDokument31 SeitenMaternal Child Nursing PDFJonalene SoltesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Blood TransfusionDokument10 SeitenBlood TransfusionMitch SierrasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Gross Anatomy Syllabus-Fall 2010-2011Dokument16 SeitenHuman Gross Anatomy Syllabus-Fall 2010-2011Zeina Nazih Bou DiabNoch keine Bewertungen

- NCLEX Questions OB QuestionsDokument4 SeitenNCLEX Questions OB QuestionsAlvin L. Rozier100% (1)

- Axial DeformityDokument58 SeitenAxial DeformitynishantsinghbmeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Open Bite, A Review of Etiology and Manageme PDFDokument8 SeitenOpen Bite, A Review of Etiology and Manageme PDFVieussens JoffreyNoch keine Bewertungen

- AttachDokument27 SeitenAttachHervis FantiniNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4th BDS Books ListDokument8 Seiten4th BDS Books ListZION NETWORKNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supp Hip OnlyDokument20 SeitenSupp Hip OnlyMark M. AlipioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Health Teaching Plan For Infants, Toddlers, Preschoolers, Schoolers, and Adolescents Based On The FollowingDokument23 SeitenHealth Teaching Plan For Infants, Toddlers, Preschoolers, Schoolers, and Adolescents Based On The FollowingCristina L. JaysonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Advertisement For Asst Prof JUN 2020Dokument7 SeitenAdvertisement For Asst Prof JUN 2020Sashikant PandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Guide For Monitoring Child Development in Low - and Middle-Income CountriesDokument11 SeitenA Guide For Monitoring Child Development in Low - and Middle-Income Countriesanisetiyowati14230% (1)

- Pediatrics A Competency Based CompanionDokument6 SeitenPediatrics A Competency Based CompanionNabihah BarirNoch keine Bewertungen

- CAMERON Current Surgical Therapy, Thirteenth EditionDokument1.667 SeitenCAMERON Current Surgical Therapy, Thirteenth Editionniberev100% (2)

- Pathogenesis of Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma: Ournal of Linical NcologyDokument9 SeitenPathogenesis of Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma: Ournal of Linical NcologyZullymar CabreraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arthroscopic Revision Rotator CuffDokument10 SeitenArthroscopic Revision Rotator CuffPujia Cahya AmaliaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Important Pediatrics SyndromesDokument11 SeitenImportant Pediatrics SyndromesYogeshRavalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Obstetrics by 10 Teachers (18th Ed.)Dokument354 SeitenObstetrics by 10 Teachers (18th Ed.)keshanraj90% (10)

- Spear-Technique Tips Making Excellent Impressions in Challenging SituationsDokument3 SeitenSpear-Technique Tips Making Excellent Impressions in Challenging SituationsIndrani DasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Normal Stages of Child DevelopmentDokument3 SeitenNormal Stages of Child DevelopmentIzzatul HaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fanem 1186 Infant Incubator - User ManualDokument78 SeitenFanem 1186 Infant Incubator - User ManualrobinsongiraldoNoch keine Bewertungen

- OraMedia Dental Self SufficiencyDokument2 SeitenOraMedia Dental Self SufficiencyJames MartinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cara Menulis Daftar PustakaDokument2 SeitenCara Menulis Daftar PustakaRani ChesarNoch keine Bewertungen