Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

China N Persian Gulf PDF

Hochgeladen von

Adit SepriyanaOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

China N Persian Gulf PDF

Hochgeladen von

Adit SepriyanaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

China and the Persian Gulf: Energy and Security Author(s): John Calabrese Source: Middle East Journal,

Vol. 52, No. 3 (Summer, 1998), pp. 351-366 Published by: Middle East Institute Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4329217 . Accessed: 07/10/2011 04:48

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Middle East Institute is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Middle East Journal.

http://www.jstor.org

CHINA AND THE PERSIAN GULF: ENERGY AND SECURITY

John Calabrese

Energy cooperation is the dominantaspect of expanding relations between China and the Persian Gulf countries. Propelling this is China's increasing reliance on Gulf oil imports.In pursuing its objectives in the Gulf, China has encounteredas many challenges as opportunities-in theform of regional crises and conflicts, as well as US pressure. In seeking to balance its geopolitical and economic interests in the Gulf, China has proceeded cautiouslyand pragmatically. Yet,the possibility that China's arms transfersto Gulf countries and its positions on Gulf issues may have a negative impact on regional security cannot be ruled out.

Sincethe Cold War ended, the debate in the West, especially in the United States, about the nature and implications of China's foreign policy has sharpened. The disintegration of the Soviet Union, coupled with the robust growth of the Chinese economy, have prompteda reexaminationof China's role within as well as outside the Asia-Pacific region. Some have arguedthat China's militarymodernizationprogram,the hegemony and values of the Chinese CommunistParty (CCP), and the tendency of great powers to act boldly make China a potential security threat.Othershave maintainedthat China's internalproblems,non-imperialistic tradition,and comparativelylimited abilityto

at the Middle East Instituteand AdjunctProfessor of Foreign Policy in John Calabrese is Scholar-in-Residence The WashingtonSemester Program at The American Universityin Washington,DC.

MIDDLE EAST JOURNAL* VOLUME 52, NO. 3, SUMMER 1998

352 * MIDDLE EAST JOURNAL

project military power will ensure that China will behave more cooperatively in world ' affairs. The debate over the "Chinathreat"has focused on the Asia-Pacific region, where China's cultural and economic links are most extensive, where its military assets are concentrated, and where its claims to sovereignty over territory (Tibet, Taiwan and Macau, and the South China Sea islands) are lodged. Yet, China's foreign policy and the the 1990s, concernsthatit has raised also encompassthe PersianGulf. Indeed,throughout Beijing's policy towardthe Gulf has been closely scrutinized,particularly by US officials and primarilybecause of Chinese armstransfersto Iran,and China's cooperationwith that country in the field of nuclear energy. China's commercial military activities certainly deserve the attention they have received, but the preoccupationwith those activities has tendedto obscurethe context and distort the content of Chinese policy toward the Persian Gulf. The Gulf is no longer of peripheralstrategicsignificanceto China,nor is Chinaany longer a marginalplayer in the Gulf or, for that matter, in the Middle East. In recent years, Sino-Gulf relations have entereda new and important stage of development.A decade ago, armssales were the core of China's interactionwith the region. Today, however, complex energy linkages between China and the Gulf countries are developing. Before long, these linkages will constitute a major, if not the dominant, feature of Sino-Gulf relations. This study addresses two importantquestions:How have these growing energy ties shaped,and been shapedby, the political and strategic aspects of China's interests in the region? And, will intensifying exert a moderatinginfluenceon Chinese foreign policy Sino-Gulf energy interdependence behavior both in the Gulf and Asia-Pacific regions? AND MODERNIZATION GEOPOLITICS Since the early 1980s, China's leaders have sought to develop a foreign policy that reconciled the requirements of modernization with geopolitical considerations. With respect to China's policy toward the Persian Gulf, balancing these interestshas become more complicatedin the 1990s because of shifts in the global strategicbalance of power, and the widening scope of China's economic involvement with the Gulf region. Chinese officials have long regardedthe Persian Gulf as an area of global strategic importance. Their views on the significance of the Gulf have been derived from periodic assessments of the majortrendsin world affairsand their probableimpact on China. In the post-Cold War period, China's leaders have identified three dominant features of international relations: an intensification of economic competition, the ascendancy of ethnic and religious sources of political identity and expression, and a tension between the forces of multipolarityand unipolarity.These assessments have served as the frameworkwithin which former premierDeng Xiaoping and his successors have interpretedevents in the Persian Gulf and have fashioned responses to them.

1. For a good review of this debate, see Denny Roy, "The 'China Threat' Issue," Asian Survey 36, no. 8 (August 1996), pp. 758-86.

CHINA AND THEPERSIAN GULF * 353

Chinese officials assert that economics has taken precedence over politics, and that this is reflected in the foreign policies of governments worldwide. Chinese leaders themselves emphasize the economic aspects of 'security' and define power in 'comprehensive,' ratherthan in strictly military,terms. They regardthe accumulationof national wealth as vital to China's military modernization,to its enhanced global status and prestige, and no doubtto theirown legitimacy.2They are committedto building a socialist marketeconomy and, while they view the world situation as generally favorable to the country's development,3they have expressed misgivings about "sharpeningeconomic competition"4and the possibility that China might lag behind global economic and technological advances.5 The critical importanceof oil (and gas) to the global balance of power has not been lost on Chinese officials. They recognize that Russia's economic transition, Asia's economic growthand, increasingly,China's own economic developmentdependon these energy resources. They also recognize that oil exporting countries are redefining their relationshipswith the world marketand with international oil companies.Because of the Gulf's vast energy reserves, Chinese officials regard the region to be of long-lasting geo-economic and geopolitical significance.6As will be shown, because of the energy challenges China itself faces and the foreign commercial opportunitiesthat the Chinese energy industryseeks, the Gulf has become importantto the country's economic future. Accentuatingthis importanceis the Gulf's potentialas a marketfor Chinese products,and as an access point for the re-exportof this merchandiseto the rest of the Middle East and East Africa. Second, the increased incidence of ethnic- and religious-basedturmoil aroundthe world has worriedChinese leaders.Their apprehensionstems from the close proximityto China of some of these conflicts, such as those in Afghanistanand Tajikistan;and from ties that furnish separatistand other opposition groups with moral and the transnational material support. Of special concern to China's leaders is the potentially destabilizing effect of these conflicts and transnationalforces on China itself, and especially on the Xinjiang province, where a comparativelylarge numberof Muslim minoritiesreside and where political disturbanceshave occurredwith increasingfrequency in recent years.7 Historically, Chinese rulers have regardedCentralAsia and the Gulf as parts of a single entity. From as early as the 1979 IranianRevolution, and with heightenedurgency since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Chinese officials have wrestled with the issue of

2. See, for example, RobertTaylor, "ChinesePolicy towardsthe Asia-Pacific Region: Contemporary Perspectives,"Asian Affairs 25 , no. 3 (October 1994), pp. 261-63. 3. See, for example, remarksby Qian Qichen, Xinhua News Agency, Foreign BroadcastInformation Service - China (FBIS-CHI), 30 May 1996. 22 December1995. 4. See remarks QianQichen,XinhuaNews Agency,FBIS-CHI, by ForeignMinister 5. See Bonnie Glaser, "China's Security Perceptions," Asian Survey 33, no. 3 (March 1993) pp. 262-63. 6. Regarding China's oil needs and oil industry, see Premier Li Peng's remarksat the 15th World PetroleumConference in China, FBIS-CHI, 30 October 1997. 7. See Raphael Israeli, "A New Wave of Muslim Revivalism in China,"Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs 17, no. 2 (October 1997), pp. 269-82. See also Hong Kong Agence FrancePresse in FBIS-CHI, 11 June 1997, and South China Morning Post (Hong Kong) in FBIS-CHI, 19 March 1997.

EASTJOURNAL 354 * MIDDLE

how to maintaintheir tenuous control over the country's western provinces. In an effort to containunrestthere, Chinese authoritieshave tried to build goodwill with theirIranian, Saudi and Central Asian counterparts. Largely in order to combat the potentially in the frontierregions, China has taken steps disintegrativeeffects of underdevelopment to create an "Islamic circle" of development8that links the economies of its border provinces with those of CentralAsia and the Persian Gulf.9 Third,as in the past, Chinese officials disapproveof the presence of foreign military forces in the Gulf. They characterizeUS military involvement there as "interference."10 They suspect the United States of wanting to dominate the region in order to exercise control over the Gulf's energy resources.1' The expanded US military presence in the region, and the absence of a strategiccounterweightto the United States,have fueled these suspicions. The role of Russia in the Gulf is an additionalconcern for China. Recently, Russia has made a strong bid to restore and expand its involvement in the region. Because Chinese and Russian positions on salient Gulf issues (e.g. UN sanctions against Iraq) closely correspondand, because Sino-Russianrelations generally are productive,Russia does not represent an immediate threat to Chinese interests in the Gulf. However, the possibility that China and Russia may become rivals ratherthan partnersin the Gulf and elsewhere has bolstered China's determinationto consolidate its relationshipswith Gulf countries. THE ECONOMICDIMENSION During the 1990s, energy cooperationemerged as the dominantfeatureof Sino-Gulf relations. This evolving energy relationshipis itself part of the changing patternof the global energy market,in which Asian-Pacificcountriesare on their way to becoming the Gulf energy producers'most importantcustomers.'2The expansion of Sino-Gulf energy

8. In 1988 China's centralplanners"opened"the economy to the outside world by designatingcoastal areas as development zones and by integratingthese with the economies of its Asian neighbors. Recently, Chinese officials have extended this model to WesternChina, a comparativelybackwardarea that they hope to bind to the economies of the Gulf and Central Asia. The "development circle" signifies China's zone of developmentand its neighbors'economies. See Gaye Christoffersen, "Xinjiangand the GreatIslamic Circle:The Impactof Transnational Forces on China's Regional Economic Planning,"China Quarterly133 (March 1993), pp. 130-51. 9. For a discussion of the connection between domestic unrest and China's relations with Islamic countries,see Lillian CraigHarris,"Xinjiang,CentralAsia and the Implicationsfor China's Policy in the Islamic World," China Quarterly, 133 (March 1993), pp. 111-29; and Dru C. Gladney, "Sino-Middle Eastern Perspectives and Relations,"InternationalJournal of Middle East Studies 26, no. 4 (1994), pp. 677-91. 10. "Round-upOn Developments in the Gulf Region," Xinhua News Agency, FBIS-CHI,26 December 1995. 11. See Asia Times, 12 November 1996. 12. The Sino-Gulf energy relationshipis markedby four main trends. First, the Asia-Pacific region as a whole has become an "energydemandgrowth center."Second, surgingoil consumptionis eroding the ability of Asian-Pacificcountriesto meet theirrequirements merely by relying on domesticproductionand importsfrom within the region. Third, importedoil forms a growing share of Asian oil supplies, and oil from the Gulf is a growing proportionof these imports. Fourth,the United States and WesternEuropeancountrieshave begun to shift their oil purchasesaway from the Gulf and towardother producingareas.For discussions of energy trends in the Asia-Pacific region, and the energy-securitynexus, see, for example, FereidunFesharaki,"The Energy

CHINA AND THE PERSIAN GULF * 355

ties is propelled primarilyby changes in the Chinese economy. China's interest in Gulf energy resourcesreflects a widening gap between its energy needs and its ability to fulfill them. Althoughcoal is China's leading energy source, oil is nonethelessvitally important to the well-being of the Chinese economy. Oil alreadyrepresents17 percent of China's total primaryenergy requirements.'3 It is likely to become an even largerfractionof the energy mix as China struggles to cope with environmentalchallenges. Meanwhile, the volume of oil consumed in China is sharply rising. Between 1990 and 1995, China's average annual oil consumptionvolume rose at a rate of 6.4 percent.14 The Centre for Global Energy Studies (CGES) in London estimates that Chinese oil demandwill reach seven million barrels per day (bpd) by the year 2005.15 China's crude oil imports are expected to rise from 440,000 bpd in 1996 to perhapsas high as one million bpd in the year 2000.16 Paralleling China's increasing demand for crude oil is its growing appetite for oil products,'7which has outpaced the growth of China's processing capacity. Since 1985, China's crude oil refining capacity has expanded at the uncommonly fast rate of five percentannually.Althoughby the early 1990s Chinahad attainedthe fourthlargestcrude oil processing capacity in the world (after the United States, Russia and Japan),'8it had nonethelessbecome a net importerof plastics, fibers,naturaland syntheticrubbers,a wide range of other petrochemicalproducts,and petrochemicalfeedstocks.'9 Chinese energy analysts have asserted that, because of the expanding gap between domestic production and demand, increased reliance on oil imports is "unavoidable." Anticipatingthe need to import50 million tons of oil annuallyby the year 2000 (or double the amountpurchasedin the mid-1990s), they have urged the governmentto develop an "outward-lookingoil economy."20Some have advocated comprehensive changes in China's oil policy, includingthe developmentof a "strategicoil-supply securitysystem"2' that would entail the constructionof new loading, storage and processing facilities, and possibly tankerfleets. In the interestof ensuringenergy security,Chinese authoritieshave endorsedmajor new efforts by the domestic oil industryto engage in overseas activities; moreover,they have authorizedand promoted foreign participationin China's oil sector.22As a direct

Supply and Demand Outlookin the Asia-PacificRegion," OPECReview 16, no. 3 (Summer 1992), pp. 119-3 5; Masayasu Ishiguro and Takamasa Akiyama, Energy Demand in Five Major Asian Developing Countries (Washington,DC: The World Bank, 1995). 13. See remarksby Hu Angang, researchfellow of the National ConditionsAnalysis and Study Group of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Xinhua News Agency, FBIS-CHI, 3 March 1997. 14. Ibid. 15. Cited in Middle East Economic Digest 41, no. 44, (31 October 1997), p. 3. 16. Middle East Economic Survey40, no. 24, (16 June 1997), p. A3. 17. Petroleum Economist, March 1995, p. 10. 18. Ibid. 19. See Kang Wu and James P. Dorian, HydrocarbonProcessing 74, no. 3 (March 1995), pp. 40-46. 20. See, for example, Shen Qinyu and Wu Lei, "Focus on the Gulf Region in Developing the Oil FBIS-CHI, 6 February1995. Industry," 21. See remarksby Zhu Yu, presidentof SINOPEC'sEngineeringand PlanningInstitute,Xinhua News Agency, FBIS-CHI, 11 June 1997. 22. Xinhua News Agency, FBIS-CHI, 28 December 1995.

356 * MIDDLE EAST JOURNAL

result of the decisions to acceleratecooperationwith foreign entities and expand overseas operations,China's energy ties with the Gulf countries have grown. Althoughuntil the early 1990s Chinaobtainedmost of its importedoil from southeast Asian producers(mainly Indonesia),this has begun to change. An increasingproportion of the oil outputof Asian producersserves their own domestic markets.China, therefore, is unsure about how much oil it can import, and for how much longer it can rely on its neighbors for its energy needs. For this reason, China has had to look elsewhere. Of the potentialalternativesuppliers,Chinese officials regardthe Gulf countriesas "key sources of China's crude oil imports."23 They are attractedto Gulf producers because of the latter's large proven reserves, idle surplus capacity and relatively low development and production costs. Other suppliers (i.e., Latin American, Central Asian and Russian producers)do not offer China this complete set of advantages. China's dependence on crude oil from the Persian Gulf has already risen and is expected to continue to do so. Between 1994 and 1997, China's reliance on the Gulf rose from 40 percent to 60 percent of its total oil imports.24According to one study, the proportionof Middle Easternsupplies in China's oil imports may surpass90 percent by the year 2005.25 Based on this estimate, one can argue that China's initiatives towardthe Gulf representthe early stages of a long-terminvolvement in the region's energy market. It is importantto note that this involvement is not confined simply to Chinese purchases of crudeoil, but also includes participation in oil explorationand development.According to its ninth Five-Year Plan (1996-2000), China aims to produce5-10 million tons of oil abroadby the year 2000.26This plan targetsthe Gulf (along with Russia and CentralAsia) as an area in which Chinese oil firms must carve a share of the petroleumprospecting market.27 Chinahas adoptednew approachesto securinga strategicfoothold in the Gulf energy market.Chinese oil firmshave negotiatedlong-termsupply contractsand have concluded productionsharingagreements28 directly with Gulf countriesas opposed to international oil companies.29 In May 1995, for example, China negotiateddirectly with Iran to triple its oil purchasesfrom 20,000 bpd to 60,000 bpd.30China's importsof crude oil from Iran are expected to increase 43 percent duringthe period 1997-98, and graduallyexpand to 200,000 bpd by the year 2000.31 In October 1997, Saudi ArabianAmericanOil Company (ARAMCO) announcedthat China would triple its crude oil imports from Saudi Arabia

23. Li Yizhong, executive vice president of SINOPEC, quoted by Xinhua News Agency, FBIS-CHI, 28 October 1994. 24. Kang Wu and FereidunFesharaki,cited by Oil and Gas Journal 95, no. 35, 28 August 1995. 25. Ibid. 26. ZhongguoXinwen She, 22 March 1996, in FBIS-CHI, 26 March 1996. See also remarksby Zhou Yongkang, vice presidentof CNPC, Agence France Presse, 28 December 1995, from Lexis-Nexis. 27. Ibid. 28. See ZhongguoXinwenShe, in FBIS-CHI,9 November 1996; and XinhuaNews Agency, FBIS-CHI, 10 November 1997. 29. See statementby SINOCHEMpresident,Zheng Dunxun, Xinhua News Agency, FBIS-CHI,6 July 1993. 30. Platt's Oilgram News, 31 May 1995; and The InternationalHerald Tribune, 15 July 1995. 31. See Middle East Economic Digest 41, no. 21, (23 May 1997), p. 22.

CHINA AND THE PERSIAN GULF * 357

to 60,000 bpd, and thatthis could increaseto as much as 350,000 bpd within the next three years.32In 1997, the China National PetroleumCompany (CNPC) concluded a preliminary production agreement with Iraq to develop the Al-Ahdab oil field southeast of projects.For Baghdad.33 Chinese oil enterpriseshave also been active in Gulf downstream example, the China PetrochemicalCorporation(SINOPEC) successfully renovated the Al-Ahmadi refinery in Kuwait after the 1991 Gulf War. Chinese firms have exhibited interest in building a fertilizer plant in Saudi Arabia similar to the Sino-Arab facility alreadyin operationin Hebei province in northernChina.34 AlthoughChinese officialsrecognize thatincreasedoil importsare unavoidable,they are determined to ensure that foreign supplies are used mainly to support domestic production.China's centralplannershave taken steps to centralizecontrolover foreign oil purchasesand to liberalizeaccess and proceduresfor foreign investmentand participation in domestic oil development.35 Foreign firms, such as ARCO, Mobil and Shell, are now engaged in petroleumprospectingand development projects in 21 Chinese provinces.36 Oil companies from the Gulf, such as ARAMCO, the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) and the Kuwait PetroleumCompany (KPC), have joined other foreign firms in bidding for such projectsin China.This breaksnew groundin Sino-Gulf energy relations, for up to this point, there had been no history of joint venturesin China's energy sector. KPC has a 14.7 percent stake in the Yacheng offshore gas field, the first such project in which China has cooperated with foreign companies since its implementation of In 1997, officials of the CNPC and the NIOC explored the possibility of such reforms.37 cooperation.38Thus, activity by Gulf companies in China's domestic oil industry is developing simultaneouslywith the involvement of Chinese firms in Gulf oil industries. In order to handle an increase in the volume of oil imports, China must expand its refining capacity and reduce the operationalinefficiency of existing facilities. The rising proportionof Middle Easternoil in China's importspresents an additionalcomplicating factor, since only a few of China's coastal refineries are designed to process sulfurcontaining crudes from the Gulf.39Centralplanners,following a tight monetarypolicy, have generally tried to restrict petroleum product imports and to augment domestic

32. See announcementby Beijing sales managerfor Saudi ARAMCO, cited in Middle East Economic Digest 41, no. 44, 31 October 1997, p. 3. 33. TheReuterAsia-PacificBusiness Report, 14 August 1996; MiddleEast EconomicDigest 41, no. 24, (20 June 1997), p. 26; Middle East Economic Survey40, no. 23, (9 June 1997), pp. 4-5; and The Washington Post, 24 May 1997, p. A25. 34. China Economic Review, May 1995, pp. 22-30. 35. Regarding Gulf investment, see remarks by Li Ben, Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Cooperation(MOFTEC),Xinhua News Agency, FBIS-CHI, 8 February1997. Note that determiningthe extent of Gulf investment in China is difficult, given that it tends to be channeled through Hong Kong and US companies. 36. Xinhua News Agency, FBIS-CHI, 13 May 1996. 37. Xinhua News Agency, FBIS-CHI, 10 January1996. 38. Reuters, 26 May 1997, from Lexis-Nexis; BBC Summaryof WorldBroadcasts, Far East, 28 May 1997, from Lexis-Nexis; and Middle East Economic Survey40, no. 24, (16 June 1997), p. 13. 39. Oil and Gas Journal 93, no. 18, 8 May 1995, p. 8; and China Chemical Reporter, 10 September 1995, p. 4.

358 * MIDDLE EAST JOURNAL

production mainly through revamping (as opposed to constructing new) refineries.40 SINOPECofficials, on the other hand, have lobbied centralplannersin orderto avoid the creation of potentialjoint venture competitorsand to obtain capital upgraderefineries.41 Saudi ARAMCO has emerged as a majorbeneficiaryof this domestic political wrangling. in the Thalinrefineryprojectin northeastern ARAMCOis the largest shareholder China,42 and has entered negotiations with SINOPEC to expand the refinery at Maoming in It has arranged to build a $1.5 billion refineryin the northeastport Guangdongprovince.43 city of Qingdao in Shangdong province, along with the China Chemicals Corporation (SINOCHEM)and the South Korean firm Ssangyong.44 The importance of this last project should not be underestimated.Significantly, centralplannersapprovedthe project, despite the fact that it grantedthe majorityequity stakes to the foreign participants, and involved SINOPEC's major Chinese rival, SINOCHEM.The deal to constructthe Qingdaorefineryincludeda commitmentby Saudi ARAMCO to supply 10 million tons of crude oil over a 30-year period.45 Although some of this oil will be dedicatedto the new refineryat Qingdao, SINOCHEMplans to process the rest at its Dalian facility in Liaoning province on China's coast. This agreement, therefore,representsthe convergence of three strategicdecisions: the first, on the part of China's centralplanners,to establish a long-termupstream-downstream relationshipwith Saudi Arabia that would involve purchasingSaudi crude oil and cooperationin refining oil; the second, on the partof SINOCHEMofficials,to lock in crudeoil importsin an effort to penetratethe domestic market,traditionallythe strongholdof SINOPEC;and the third, on the part of Saudi ARAMCO, to establish a platform from which to gain a share of Asia's growing energy market. Saudi Arabiais not alone among Gulf countriesin seeking to exploit the potentialof the burgeoningAsia-Pacific energy market.China and Iranreachedan agreementin 1997 on a joint ventureprojectto upgradea refineryin Guangdongprovince in southernChina to expandits capacityto process Iraniansour crudes.46 Chinais alreadythe biggest market for Gulf fertilizers-the leading customer for Kuwait as well as Saudi Arabia.47 Kuwait is involved in upgradingthe Qilu petrochemicalfacility in ShandongProvince.Like Saudi Arabia, other Gulf producersare positioning themselves to penetratethe China energy marketby enteringstrategicupstream-downstream agreements.Kuwait, for example, has reportedly struck a deal to construct a pipeline that serves Chinese refineries on the condition that it carries exclusively Kuwaiti crude oil.48 Thus, Gulf cooperation in the developmentof China's oil industryreveals a competitive strugglefor sharesof the China

40. Quoting a SINOPECofficial, The Reuters EuropeanBusiness Report, 26 November 1995, p. 6. 41. See remarksby Dennis Eklof, seniorconsultantat CambridgeEnergyResearchAssociates, in Platt's Oilgram News, 10 February1995, p. 3. 42. Middle East Economic Digest 39, no. 37, 15 September 1995, p. 25. 43. Xinhua News Agency, in FBIS-CHI, 6 April 1995. 44. Deutsche-PresseAgentur, 11 November 1996, from Lexis-Nexis; FBIS-CHI, 29 January1997. 45. See remarksby Chinese economic and commercialcounsellorZang Dimo, Saudi Gazette (Riyadh), 17 January1995. 46. Middle East Economic Survey 40, no. 24, 16 June 1997, p. A3. 47. China Economic Review, May 1995, pp. 22-30. 48. Ibid.

GULF * 359 CHINA AND THEPERSIAN

energy marketwaged primarilybetween the two leading Chinese oil enterpriseson the one hand, and Persian Gulf producerson the other. It is also importantto mention the linkage between China's energy importsfrom the Gulf and its economic activities in the Gulf in non-energy sectors. Increasingpurchases of Gulf oil and gas require China to devise ways to maintain balanced trade. Chinese officials have energetically sought to increase merchandise exports and industrial cooperation with Gulf counterparts.They have held discussions with Iraqi officials They have alreadysucceeded regardingcooperationin expandingIraq'sexportfacilities.49 in boosting trade with Iran, and are exploring furtheropportunitiesfor export growth.50 Although Sino-Gulfenergy cooperationis in its early stage of development,evidence of its sources, scope and ramificationshas already begun to emerge. Those Sino-Gulf energy ties not only reflectglobal energy markettrends,but also representcomplementary changes in the structuresand growth patternsof the Chinese and Gulf economies. The struggle by the Gulf's oil producingcountries to diversify their energy-centeredeconomies has intersected with the struggle by China's central planners to sustain their country's economic growth. THE POLITICAL DIMENSION In the 1990s, China developed its ties to the Middle East more rapidly and extensively thanit had at any previoustime. It establisheddiplomaticrelationswith Saudi Arabiain 1990, completing the projectof normalizingrelationswith all of the Gulf states for several reasons. that began in the early 1970s.51 This was an importantbreakthrough First, it occurredwhile Chinese authoritieswere strugglingto emerge from international isolation as the result of the TiananmenSquaremassacre.Second, it was accompaniedby the severing of diplomaticlinks between Saudi Arabiaand Taiwan, markinga victory for Beijing's "one China" policy.52 Third, it laid the groundwork for the expansion of commercialties with Saudi Arabia,with the hope thatthis would stimulatecommercewith other Gulf states as well. trackof the Arab-Israeli The multilateral peace process thatbegan in Madridin 1991 providedChina with the opportunityto play a constructiverole in the peace process and thereby earn political credit with the Arab Gulf states. China participatedin the five multilateralworking groups, chaired the Water Committee, dispatchedobservers to the 1996 Palestinianelections, and bid for membershipin the Middle East DevelopmentBank

49. See Iraq News Agency, in Foreign Broadcastand InformationService, Near East and South Asia (FBIS-NES), 7 August 1997; and Xinhua News Agency, in FBIS-CHI,4 June 1997. 50. Xinhua News Agency, FBIS-CHI, 11 November 1996; and Iran Focus, no. 3 (March 1998), p. 3. 51. For a general discussion of Chinese diplomacy in the 1990s, see James Hsiung, "China's Omni-DirectionalDiplomacy,"Asian Survey 35, no. 6 (June 1995), pp. 573-75. 52. One of the majorstumblingblocks to China's normalizationwith any countryhas been the "Taiwan issue." China has consistently conditioned its establishment of diplomatic ties on its prospective partners' willingness simultaneouslyto break or downgraderelations with Taiwan. China considers such a concession proof that its partnersendorse a "one China"policy. The Saudis, like others, agreed to this.

EASTJOURNAL 360 * MIDDLE

(MEDB).53China also capitalized on the initial progress toward peace to normalize its relationswith Israelin 1992, at a point in time when the risk of offendingArabsensibilities was relatively low. The 1990 Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, however, posed more challenges than opportumemberof the UN SecurityCouncil, Chinabecame a key nities for China.As a permanent player in efforts to mobilize an internationalresponse to Iraq's aggression.54In this respect, the Kuwait crisis provided China with an occasion to show support for the vulnerableArab Gulf monarchies.In otherrespects, however, the crisis was a setbackfor China. In their initial responses to Iraq's aggression, Chinese officials advocated an "Arab"resolution of the crisis, which in fact never materialized.Beijing's subsequent diplomaticinitiativesto persuadeIraqipresidentSaddamHusaynto withdrawIraqiforces from Kuwait were, like those of other countries, fruitless. Clearly, China preferred diplomacy to economic sanctions, and sanctions to the use of force. Ultimately, China supportedthe first ten UN Security Council resolutions against Iraq,but stopped short of endorsing UN Resolution 678 to go to war against Iraq, and steadfastly refused to participatein the military coalition.55The cost to China of the sanctions and of the war itself was substantial.According to some estimates, China incurredlosses in assets and earnings in excess of $2 billion. In addition, Kuwait suspended $300 million in development loans to China, in retaliation for China's abstention on the UN vote mandatingthe use of force against Iraq.56 The second political challenge that Chinafaced in the region occurredafterthe 1991 Gulf War. This challenge relates to the "unfinishedagenda" of the war, that is, that SaddamHusayn remainsin power and that Iraqis widely believed to have the capacity to produceweapons of mass destruction.To addressthese concerns,the United Stateshas led the effort in the UN Security Council to broaden,maintainand enforce sanctions against Iraq,the most severe of which are those prohibitingIraqioil exports. This has meant that a highly intrusive weapons inspection and monitoringregime was set up; "no-fly zones" in the northernand southern parts of the country were imposed; and the use of force against Iraq in retaliationfor violations of UN authoritywas permitted. Although Chinese officialshave called upon Iraqto comply fully with all the relevant UN resolutions,they have also expressed strongreservationsabout many of the measures taken by the UN Security Council. The infringementof Iraqi sovereignty, for instance, which China regards as an unwelcome precedent, is a subject of particularconcern. Chinese officials have objected to punitive militarystrikes against Iraq.They have stated

53. For a statementon China's contributionto the peace process, see remarksby Wu Sike, directorof the Chinese foreign ministry's West Asian and North African affairs department,Xinhua News Agency, FBIS-CHI, 4 January1997. 54. For a discussion of China's changing attitudes and role in the United Nations, specifically with reference to the Middle East, see Yitzhak Shichor, "Chinaand the Role of the United Nations in the Middle East,"Asian Survey 31, no. 3 (March 1991), pp. 255-69. 55. See Lillian Craig Harris, "The Gulf Crisis and China's Middle East Dilemma," Pacific Review 4, no. 2 (1991), p. 118. 56. See ibid., pp. 116-25.

CHINA AND THE PERSIAN GULF * 361

and of Iraqshouldbe "respected," that "thereasonableand legitimate securityconcerns"57 They that Iraq'sterritorial integrityand political independenceshould be "safeguarded."58 have maintained that sanctions have taken a huge toll on the Iraqi population and economy, and have argued for the removal of sanctions at the earliest possible date "on considerations."59 the basis of humanitarian China has benefited from the fact that, over time, these sentiments have become widely shared in the Gulf and the Arab world. For the most part, however, China has avoided challenging the United States alone on these matters.Instead, China has joined rankswith Franceand Russia in calling for the early lifting of sanctions,and in opposing tighter sanctions or the use of force in response to Saddam Husayn's defiance of UN authority.The November 1997 crisis stemming from Iraq's expulsion of the UN Special Commissionon Iraq(UNSCOM)weapons inspectorsis illustrative.China,which held the Security Council chair that month, encouraged Iraq to "play by the rules."60China's diplomats,who opposed militarystrikesagainstIraq,conferredclosely with theirRussian and French counterparts.However, China confined itself to managing the UN Security Council's deliberationsand serving as the voice of restraint.It was Russia, ratherthan China that sought and played the key diplomaticrole in defusing the crisis.6' Similarly, duringthe February1998 crisis, when Iraqagain defied the United Nations and prevented the inspectors from visiting certain sites, China worked behind the scenes to discourage the use of force. It also supported UN Secretary General Kofi Annan's diplomatic interventionand his visit to Baghdad to convince the Iraqi leader to abide by the UN resolutions. The thirdpolitical challenge that China has faced in the Gulf pertainsto Iran,where China's policy of engagement is directly at odds with the US policy of containment. Unlike the case of Iraq,US policy towardIranis not based on a multilateralinstitutional to which China is a party.Nor, as in the case of Iraq,has there ever existed arrangement consensus in favor of isolating Iran.For these reasons, a strongregional and international China has enjoyed a comparativelyfree hand in strengtheningits relationshipwith Iran. Chinese leaders view the US policy of containing Iran as a unilateral initiative, designed by the United States to ensure its predominancein the Gulf and impose its will on others.62This has served as a catalyst for China's policy of engaging Iran. Chinese to regional stability, and officials also characterizeUS policy towardIran as "unhelpful"

57. See remarksby Wang Xuexian, memberof China'sUN SecurityCouncil delegation,Wang Xuexian, 12 June 1996, United Nations Documents, Security Council, no. S/PV.3672. 58. Ibid. 59. See statementby Li Zhaoxing, memberof China's UN delegation to the Security Council, 14 April 1995, United Nations Documents, Security Council, no. S/PV.3519. 60. See remarksby Foreign Minister Qian Qichen, Xinhua News Agency, FBIS-CHI, 14 November 1997. 61. See, for example, The New York Times, 21 November 1997, p. Al; and The WashingtonPost, 21 November 1997, p. A46. 62. See, for example, remarksby Foreign MinisterQian Qichen, Xinhua News Agency, FBIS-CHI, 22 February1994.

EASTJOURNAL 362 * MIDDLE

maintainthat excluding Iranfrom Gulf and CentralAsian affairsmay backfire,leading to more disruptivebehavior by Iran and more turmoil in the region.63 China's relationshipwith Iranis conditioned,but not determinedby the 'US factor.' In contemporary history, cooperationbetween Iranand China dates from the 1970s, when the Shah of Iran was still in power. Since the fall of the Shah, this cooperationhas been based on a confluence of geostrategic interests and views, of which objection to US military involvement in the Gulf is only one element. Chinese officials regardIran as a regional power, and treat this as an unalterablegeopolitical fact. They also view Iran as a "natural" egress route for CentralAsian oil and gas, and a pivotal player in determining the extent of Russia's controlover these energy resources,and in meeting the Asia-Pacific region's energy requirements.64 Clearly, Iranconsiders its relationshipwith Chinato be a valuable asset in thwartingthe US containmenteffort.Its ties to China give Iran's foreign relationsan "easternorientation," which has become partof post-KhomeiniIran's "Asian

vocation."65

THE MILITARY DIMENSION In consolidatingrelationswith Iran,Chinahas assumedcertainpolitical risks. One of these is causing friction with the United States. Anotheris arousingmisgivings among the Gulf CooperationCouncil (GCC) states, which are ambivalentaboutIran.It is not China's engagementof Iranper se, however, thathas posed the greatestrisk of damagingrelations with the United States and with the region's other states. Rather,it is specific aspects of the military dimension of that relationshipthat are troubling. As previously mentioned, China's penetrationof the Gulf arms marketbegan duringthe Iran-Iraq War. The market was primarilydemand-drivenand remains so today. Before turning to the question of China's role as an arms supplierto the Gulf, it is useful to discuss briefly the climate of insecurity that prevails there, which is spurringthe demand for weapons. In the 1990s, the Gulf has become a highly militarized region. Although the cease-fire agreementthat ended the Iran-Iraq War has held for nearly a decade, the two countrieshave not yet signed a peace treaty. Iraq's military defeat in the 1991 Gulf War and its continuingsubjectionto internationalsanctionshave merely provided a breathing spell for Iranto re-equipits armedforces. The survivalof the SaddamHusaynregime, the possibility that Iraq's weapons of mass destructioncapabilitymight escape UN detection, and the unstable situation in northernIraq, have provided incentives for Iran's military modernizationprogram. In turn, Iran's rearmament efforts, in the context of Iraq's militaryweakening, have reinforcedthe demand for arms by the GCC states. These conditions of insecurity have also made the GCC states more dependenton US forces and more willing to accept the

63. Ibid. 64. See, for example, remarksby NationalPeople's CongressChairman Qiao Shi, XinhuaNews Agency, FBIS-CHI, 31 December 1996. 65. See, for example, remarksby Foreign MinisterVelayati, IranianNews Agency, FBIS-NES, 18 May 1997.

CHINA AND THE PERSIAN GULF * 363

stationingof these troopson their soil, which they had previouslyeschewed. Furthermore, there exist various sources of friction among the GCC states themselves, including disputes. Thus, the securityenvironmentof the Gulf is such that all unresolvedterritorial of the region's states are intent upon acquiringweapons as means of deterrence,if for no other purpose.In the context of a contractingglobal arms marketand in spite of national budgetary constraints exacerbatedby flat (or even falling) oil prices, the Gulf region remains one of the world's most lucrative arms markets.66 Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia joined China in aggressively marketingits military hardwarein the Gulf. In terms of their monetary value, China's weapons sales to the Gulf in the 1990s were roughlyon a parwith those of Russia. Despite the inroads made by China and Russia into the Gulf arms market, Western suppliers, continuedto dominateit. In fact, afterpeakingin 1988, especially US defense contractors, in China's earningsfrom arms sales to the Gulf fell steeply for seven consecutive years,67 partbecause Chinais competitivein only a relatively narrowrange of militaryproducts.68 Of the weapons sold by China to the Gulf countries, ballistic missiles are among its highest money earners.These weapons-especially if equippedwith biological, chemical or nuclearwarheads-have the greatestpotentialto destabilize the region. Thus, it is not China's involvementper se, but the natureof its involvementin the Gulf armsmarketthat

is controversial.

China's proliferationactivities, specifically with respect to Iran, its most important customerin the region, have emerged as a majorbone of contentionbetween the United States and China. In fact, US officials consider Chinese cooperationin this field to be a Consequently,China's leaders have had to "core issue" in Sino-US bilateralrelations.69 weigh the advantagesof a continuationof these armstransferpracticesagainstthe risk of seriously damaging Sino-US relations. Over the years, and especially since Chinaenteredthe Gulf armsmarketin the 1980s, have changed,and so has its policy. Withinthe China's attitudestowardnon-proliferation period 1992-93, China signed the Nuclear Non-ProliferationTreaty (NPT), agreed to observe the Missile Technology ControlRegime (MTCR)guidelines, and also joined and ratified the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC). In addition, China promulgated regulationsconsistent with internationalstandardsfor the transferof nuclearmaterials.70

66. In 1995, the Middle East remainedthe world's leading arms importingregion. In that year, its share of global arms imports climbed, even though its real growth rate declined. Within this regional market, Gulf and Arms Transfers, countriesaccountedfor over 80 percentof armsimports.See WorldMilitaryExpenditures 1996 (Washington,DC: Arms Control and DisarmamentAgency, 1997), pp. 11-13. 67. Ibid., Figure 16, Leading Exportersby Countryand Year, 1985-95, p. 21. 68. For a discussion of China's sales to Iran, see Michael Eisenstadt,"ChineseMilitary Assistance to Iran: Trends and Implications," in Barry Jacobs, ed., Chinese Arms and Technology Transfers to Iran: Implicationsfor the United States, Israel, and the Middle East (Washington,DC: Asia-Pacific Rim Institute, 1997), pp. 1-2. 69. See, for example, Robert Einhorn, US deputy assistant secretary of state for nonproliferation, "TestimonyBefore the Subcommitteeof InternationalSecurity, Proliferationand Federal Services of the US Senate Committee on GovernmentalAffairs," 10 April 1997. discussion of Sino-US nuclearcooperation,see JenniferWeeks, "Sino-USNuclear 70. For a background Arms Control Today (June/July1997), pp. 7-13. Cooperationat the Crossroads,"

EASTJOURNAL 364 * MIDDLE

the 1990s, armscontrolissues have remaineda source of friction Nevertheless,throughout in Sino-US relations. With regardto missiles, US concernshave focused on proliferationactivities covered by, as well as outside the scope of, the MTCR.In 1995, TheNew YorkTimesreportedthat, according to an internal CIA document, China provided Iran with missile guidance technology.7' In 1997, The WashingtonPost cited an unclassified CIA reportto the US Congress that alleged a variety of Chinese assistance to Iran's missile programs.72 US officials have also expressed concern about China's sale to Iranof C-801 anti-shipcruise missiles, which pose a threatto oil tankertrafficand US naval vessels deployed in the Persian Gulf.73 The case of China's cooperationwith Iran in the nuclear energy field perhapsbest illustratesthe complexity of the triangularrelationshipbetween China, the United States and Iran. Chinese officials have admittedcontributingto Iran's nuclear energy program, but have denied supplying fissionable material or other weapons-relatedtechnologies.74 They have also denied knowing of any attempt by Iran to divert nuclear materials to weapons production.Furthermore, they, like their Iraniancounterparts, have assertedthat Iran has satisfied International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) monitors that its nuclear programis intended for peaceful purposes only.75 In October 1997, China took what might be a significant step to accommodatethe United States: It provided a written pledge to refrain from engaging in "new nuclear It is unclear,however, which of China's suspended cooperationwith Iranof any kind."76 nuclear contracts or projects in progress this pledge encompassed, or whether US and Chinese officials held identical views about what the pledge specifically prohibited. The context in which China's nuclear nonproliferation pledge was made reveals the ways in which Chinese proliferation practicesin the Gulf region and Sino-US relationsare intertwined.Chinamade this commitmentduringChinese presidentJiang Zemin's visit to Washington in October 1997.77 This summit meeting, the first held in eight years, followed a difficultperiod in Sino-US relations,the low point of which had been the crisis over Taiwan.78Significantly,in January1998, US presidentBill Clinton announcedthat he would certify to the US Congress China's nonproliferation credentials.This paved the

71. The New YorkTimes, 18 September 1995, p. Al. 72. The WashingtonPost, 2 July 1997, p. A20. 73. Regardingthe dangersposed by Chinese assistance to Iranto improve the latter's missile guidance systems, see Paul Wolfowitz, formerUS undersecretaryof defense for policy, "Statement Before the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee,"7 October 1997. 74. This cooperation includes a Sino-Iranianagreement to build two Qinshan-class 300MW power reactorsat Darkhovin,and the sale of calutronsfor Iran's 27MW and 30MW researchreactors. 75. For an example of reportsof "secret"Sino-Iranian nuclearcooperationthat surfaceperiodically,see the discussion of a 1991 "secret"agreementin which China pledged to supply Iranwith a uraniumhexafluoride plant, in Al Venter, "Iran'sNuclear Ambition: Innocuous Illusion or Ominous Truth?"InternationalDefense Review (Supplement), 19 September 1997, p. 23. 76. James P. Rubin, US State DepartmentPress Briefing, 30 October 1997. 77. For furtherdetails on China-US nuclear energy cooperation,see The Financial Times, 23 October 1997, p. 3; The WashingtonPost, 25 October 1997, p. Al; and The WashingtonPost, 30 October 1997, p. A15. 78. In response to statements by Taiwanese officials in support of Taiwan's independence, China conducted large scale military exercises and missile tests in the Taiwan straits. This precipitateda crisis in Sino-US relations.

CHINA AND THE PERSIAN GULF * 365

way for Sino-US nuclearcommerce to resume underthe US-China Nuclear Cooperation Agreement, which authorizes American firms to engage in China's nuclear energy industry.79 These quid pro quos are illuminatingin two respects. First, they demonstrate that China's proliferationpractices in the Gulf region are sensitive to, if not dependent upon, the overall state of Sino-US relations. Second, they suggest that China's proliferation practices,at least in the nuclearfield, may be responsive to changes in the incentive structuregoverning the US approachto China. The apparentprogress made by China and the United States in the nuclear field, however, has not carriedover into the areas of ballistic missiles and chemical weapons. In neitherof these two cases has Chinaprovidedexplicit assurancescomparableto those offered in the nuclearfield. It is also premature to conclude that China will strictly abide by its nuclearpledge, or that it is even likely to do so over the long term. On 13 March 1998, six days before President Clinton's certificationbecame official, The Washington Post reportedthat the National Security Agency had interceptedmessages concerning negotiations for sale by China of uranium enrichment chemicals to Iran.80Although Chinese authoritiesresponded quickly to a US demarche, halting the transaction,this episode casts doubts upon China's intentionsto respect its promises. What, then, are the principalfactorsthatmight spurthe continuationof China's arms proliferationactivities in the Gulf region? Clearly, it is impossible to separateChina's proliferation activities from the totality of Sino-US relations. Chinese leaders have a respect for, but a residual mistrustof the use of US power. Arms sales provide a wedge for China into the Gulf, a region of global geopolitical importance and of growing significance to China itself where the United States is the preeminentpower. Those sales serve as a lever for Chinato ensurethatits interestsin the Gulf aregiven due consideration by Washington. They are also a hedge against the possible deteriorationof Sino-US relations. Economic considerationsalso apply, thoughnot in exactly the same manneras in the past. Whereascommercialarms export earningsin the 1980s mainly served China's own militarymodernizationprogram,possible new economic motivationscould exist beyond the horizon. Until now, flat or declining oil prices have largely sheltered the Chinese economy from the adverse effects of rising dependence on oil imports from the Gulf. China's oil bill is sure to rise, due to increasedfutureimportsandperhapshigheroil prices as well. This in turn could lead to an arms-for-oilarrangement, although that is by no means inevitable. Innovative payment schemes could be developed to alleviate trade imbalances between China and the region. In the longer term, the expansion of China's merchandiseexports to the region could absorb some of the cost of its oil imports. but neglected factor,is pressureby Gulf oil-producingcountrieson A final important, China to continue its arms sales. The case of Iran is instructive. Iranianleaders have

79. The WashingtonPost, 18 March 1998, p. A21. 80. The WashingtonPost, 13 March 1998, p. Al.

EASTJOURNAL 366* MIDDLE

and "strategic,"8' and have sought describedtheir relationswith China as "fundamental" to formalize this relationshipto a degree which, until now, China has resisted.82Kuwait also reportedlysought to extract security guaranteesfrom China in exchange for pledges to invest in the latter's energy industry.83 Therefore,in the absence of a modus vivendi among the Gulf countriesthemselves, andbetween individualGulf states, such as Iranand Iraq,and the United States, China is likely to face pressureto accept some sort of linkage between its own energy security and the military security of its Gulf partners. CONCLUSION In the 1980s, China laid the foundationfor multifacetedrelationswith the countries of the Persian Gulf. Chinese diplomacy in the region was geared towards building commercial ties to the region and remaining at a cautious distance from the region's complicatedpolitical problems.Withinthe span of less than a decade, Chinabegan to win laborand engineeringcontracts,andpenetratedthe Gulf armsmarket.These achievements markedthe beginning of a permanentinvolvement by China in the region. In the 1990s, China's relationswith the Gulf countrieshave become more substantial and nuancedthan is generally recognized. On the political front, China has succeeded in opening and maintaininga dialogue with all of the region's states, despite and perhaps because of their conflicts with one another.On the economic front, Sino-Gulf business linkages have become more complex and consequential,especially in the energy sector, where China's growing reliance on Gulf crude oil is the key element of intensifying cooperation.On the militaryfront, China has retaineda primarycustomer,Iran,and thus its foothold in the Gulf arms market. Yet, as China's interestsand activities in the Gulf have developed, they have become more difficultthan in the past for Beijing to manage.The 1991 Gulf War and its aftermath have illustratedthat it is impossible for Chinato insulateitself from the adverseeffects of events that transpirein the region. The case of Iranhas demonstrated that it is impossible for China to prevent its policy towards the Gulf from impinging on its bilateral relationship with the United States. As the scope of China's involvement in the Gulf widens, China may encounter many more economic opportunities,but may also incur higher political risks.

81. See remarksby Iranianvice presidentHasan Habibi, IranianNews Agency, FBIS-NES, 30 August 1994. 82. See comments by Chinese presidentJiang Zemin, who referredto the "commonoutlooks"of China and Iran, but indicated that Sino-Iranianrelations were not directed against third countries, Iranian News Agency, FBIS-NES, 28 March 1995. 83. These were the concerns that reportedlylay behind the March 1995 Sino-Kuwaitmemorandumof on military cooperation.See Reuters World Service, 14 March 1995, from Lexis-Nexis. understanding

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Globalism in The Schools: Education or Indoctrination?Dokument11 SeitenGlobalism in The Schools: Education or Indoctrination?Independence InstituteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aleksandre Zibzibadze - International Business Confirmation PaperDokument81 SeitenAleksandre Zibzibadze - International Business Confirmation PaperAlexander ZibzibadzeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Annotated BibliographyDokument26 SeitenAnnotated BibliographyJace ThornleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Analysis of The 'New World Order' and Its Implications For U. S. National StrategyDokument41 SeitenAn Analysis of The 'New World Order' and Its Implications For U. S. National StrategyJohn GreenewaldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 7 - Great Leap Forward & Five Year Plans Student Handout DONEDokument6 SeitenUnit 7 - Great Leap Forward & Five Year Plans Student Handout DONEMiah MurrayNoch keine Bewertungen

- FM 100-2-1 The Soviet Army - Operations and TacticsDokument193 SeitenFM 100-2-1 The Soviet Army - Operations and TacticsBob Andrepont100% (6)

- 5224 Ethiopian State Support To Insurgency in SudanDokument25 Seiten5224 Ethiopian State Support To Insurgency in SudanGech DebNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction and Defining GlobalizationDokument5 SeitenIntroduction and Defining GlobalizationCarla Marie AldeguerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lectures To ParentsDokument29 SeitenLectures To Parentsapi-3705112Noch keine Bewertungen

- Morgenthau's Unrealistic RealismDokument15 SeitenMorgenthau's Unrealistic Realismjaseme7579100% (1)

- Meyerhold and StanislavskyDokument47 SeitenMeyerhold and StanislavskyDavid Herman100% (1)

- SCHMELZ-What Was "Shostakovich," and What Came Next (2007)Dokument43 SeitenSCHMELZ-What Was "Shostakovich," and What Came Next (2007)BrianMoseleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- SST NtseDokument216 SeitenSST NtseWbiq Jb qvaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Task 118719Dokument9 SeitenTask 118719Maria Carolina ReisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Boris Groys Postcommunist Postscript - R PDFDokument2 SeitenBoris Groys Postcommunist Postscript - R PDFmameuszNoch keine Bewertungen

- Revolt in The EastDokument14 SeitenRevolt in The Easttao xuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Four Press TheoriesDokument10 SeitenFour Press TheoriesMuhammadSaeedYousafzaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Socialism in Europe and The Russian Revolution WORKSHEETDokument5 SeitenSocialism in Europe and The Russian Revolution WORKSHEETAnti PsxcqyNoch keine Bewertungen

- AP European History UbdDokument10 SeitenAP European History Ubdcannon butlerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bolshevik Revolution Organized CrimeDokument416 SeitenBolshevik Revolution Organized CrimeJorge Paulo100% (1)

- None Dare Call It Treason - NodrmDokument260 SeitenNone Dare Call It Treason - NodrmHaruhi Suzumiya100% (6)

- The Formation of The Chinese Communist Party - Ishikawa YoshihiroDokument24 SeitenThe Formation of The Chinese Communist Party - Ishikawa YoshihiroColumbia University PressNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kennedy Assassination: Oswald As Manchurian CandidateDokument55 SeitenKennedy Assassination: Oswald As Manchurian CandidateTom Slattery100% (8)

- Dangerous States - Nills ChristieDokument14 SeitenDangerous States - Nills ChristieJosé Luiz Cristovão Farinha FilhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- E. H. CarrDokument38 SeitenE. H. CarrMarios DarvirasNoch keine Bewertungen

- 62 Photos DavidkingDokument3 Seiten62 Photos DavidkingThyago Marão VillelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 35 - Franklin D. Roosevelt and The Shadow of WarDokument4 SeitenChapter 35 - Franklin D. Roosevelt and The Shadow of WarloveisgoldenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Us Foreign PolicyDokument13 SeitenUs Foreign Policyapi-242847854Noch keine Bewertungen

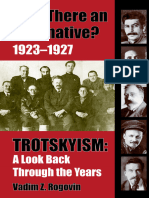

- Vadim Z. Rogovin - Was There An Alternative - Trotskyism - A Look Through The Years (2003, Mehring Books) - Libgen - LiDokument604 SeitenVadim Z. Rogovin - Was There An Alternative - Trotskyism - A Look Through The Years (2003, Mehring Books) - Libgen - LiwoflNoch keine Bewertungen

- Annotatedbibliography 3Dokument13 SeitenAnnotatedbibliography 3api-347614159Noch keine Bewertungen