Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Coaching & Mentoring Research

Hochgeladen von

Lucas PadrãoCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Coaching & Mentoring Research

Hochgeladen von

Lucas PadrãoCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Technical

Briefing

JANUARY 2002

DEVELOPING AND PROMOTING STRATEGY

Mentoring and Coaching An Overview

s

Defining coaching and mentoring Differences between a coach and a mentor Mentoring and coaching parallels Finding a coach or a mentor Barriers to effective coaching and mentoring Reciprocity of relationships Feedback and performance measurement Setting up a mentoring or coaching procedure Benefits of coaching and mentoring in organisations Links to good management Corporate strategy References and further reading

IMA has been saying for a while now that finance professionals need to acquire a much broader set of skills if they are to survive in the world of modern business. The pace of change partly driven by the advances in information technology and the pervading influence of globalisation has become relentless. The complexity of work has increased while career paths have become less obvious due to the flattening of organisational structures. The skills and knowledge that were sufficient even 50 years ago are now proving to be inadequate. Managers and executives are having continually to acquire new skills, be it in IT or organisational strategy. The traditional method of one-off instruction designed to equip an individual with enough knowledge to last a lifetime has been superseded by the concept of lifelong learning. As far back as 1977, Gross wrote: Lifelong learning means self-directed growth. It means understanding yourself and the world. It means acquiring new skills and powers the only true wealth you can never lose. It means investment in yourself.

s s

he Financial Management Accounting Committee (FMAC) of the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC) is about to publish a paper entitled The Role of the Chief Financial Officer in 2010. Amongst the CFOs and FDs interviewed, there seems to be a general consensus that the nature of finance professionals tasks is changing to encompass a much wider set of skills. Angela Holtham from Nabisco, for example, pointed out that this evolution is leaving the traditional underpinning of the finance role behind and embracing a much wider and more common range of responsibilities. The role is changing from being The Guardian of the Books to the business side and away from the transaction side.

I

For further information please contact: Technical Services: Tel: +44 (0)20 7663 5441 Fax: +44 (0)20 8849 2468 technical.services@cimaglobal.com

t is not surprising, then, that individuals and organisations are struggling to find new ways of learning that will reflect the varied and complex demands of a modern workplace. Recent years have witnessed the emergence of coaching and mentoring in many companies alongside the more traditional training methods. This briefing attempts to give a broad overview of the concepts involved, as well as some basic pointers about the practicalities of establishing a corporate coaching or mentoring scheme.

TECHNICAL BRIEFING

MENTORING AND COACHING

here is no longer a point in ones career where one can stop learning. People change jobs much more frequently nowadays and are faced with new responsibilities. Increased flexibility demands a broader spectrum of skills. This is especially true for finance professionals. Over the last decade, their roles have been expanding to accommodate knowledge from other disciplines and overlapping with other organisational functions. But, whereas many will be given enough support to advance the specialist side of their knowledge (whether in their workplace or through professional bodies such as CIMA), most will be left with little time or opportunity to improve their soft skills such as communication, listening and team-work. raditionally, these have not been the sort of skills accountants acquired through their professional or academic training or were able to utilise in their everyday work. The emphasis until recently had weighed heavily on the technical side. However, disregarding these skills could leave finance professionals seriously disadvantaged in an environment that increasingly favours inter-functional, joined-up practices.

Definitions of coaching and mentoring

Despite what some HR consultants may tell you, coaching and mentoring are not recent phenomena. Edification of some kind has existed since Homers Mentor advised Odysseus and thus lent his name to this very human activity. It was probably the goddess Athena herself, disguised as Mentor, who guided Odysseus son Telemachus in search for his father. Whatever the case, these wise and trusted counsellors have remained a feature of human interactions throughout history. The common noun mentor was first recorded in 1750. Interestingly, the etymology of the noun coach is actually Hungarian. It is derived from the word for a vehicle or a carriage the idea being that instructors carried their pupils! Of course, the connotations of both of these words have widened significantly since they were first recorded. Their relatively recent adoption into HR theory and practice has turned them into verbs, implying institutionalised training strategy. According to a survey of training managers by the CIPD in 1999, some 87 per cent of UK companies have some kind of a coaching or mentoring scheme. There is certainly no shortage of books, papers and conferences on the subject. There are many kinds of coaching and mentoring from life coaching to mentoring schemes designed exclusively for women or minorities to corporate peer-to-peer mentoring or buddy systems. In this briefing, we are specifically referring to coaching and mentoring in an organisational context, whether formal or informal. (There are significant differences between the formal and informal approaches see Ehrich and Hansford, 1999.)

word of warning, however there is no universal definition of either of these terms and therefore of the difference between them. There will inevitably be some who disagree with the citations below. This is why we list three similar though not identical sources. A recent article in the Financial Times (Clutterbuck, 2001) succinctly highlighted the main features of each as well as their differences:

Coaching is concerned primarily with performance and the development of definable skills. It usually starts with the learning goal already identified...The most effective coaches share with mentors the capability to help the learner develop the skills of listening to and observing themselves, which leads to much faster acquisition of skills and modification of behaviour. Coaches also share with mentors the role of critical friend confronting executives with truths no one else feels able to address with them. Whereas the coach is more likely to approach these issues through direct feedback, the mentor will tend to approach them through questioning processes that force the executive to recognise the problems for themselves. Mentoring is usually a longer-term relationship and is more concerned with helping the executive determine what goals to pursue and why. It seeks to build wisdom the ability to apply skills, knowledge and experience in new situations and to new problems.

The Coaching and Mentoring Network summarises it like this:

s

Differences between a coach and a mentor

So how do we define these activities? It is worth pointing out at the beginning that although they are distinct in both the format they adopt and the desired outcomes there are sufficient similarities and overlaps to allow us to occasionally use them as synonyms in this briefing. A

2

Coaching: focuses on achieving specific objectives, usually within a preferred time period. Mentoring: follows an open and evolving agenda and deals with a range of issues.

TECHNICAL BRIEFING

MENTORING AND COACHING

Benabou and Benabou (2000) present the differences in a tabular form: Coach

Protgs learning is primarily focused on abilities Technical or professional focus

Mentor

Learning is focused on attitudes

Focus on personal and professional development Helps the protg realise his/her potential More interaction with an affective component Is a role model

sion making, at whatever level of concern. It is not about giving the right answers the mentee probably already knows them. This is why coaches and even mentors dont have to have the same level of technical expertise as their protgs. Their task is not to magically solve the problems but to question how you go about looking for solutions. It is not psychological mollycoddling or a substitute for hard work. Neither are one-off events but processes with distinct evolutionary stages. As individuals attain specific goals and learn new behaviours, the goalposts move accordingly until both participants are satisfied that the overall objective has been achieved. That objective can be anything from a complete career change to learning a new procedure.

Effective use of the protgs existing competencies Professional interaction with the protg Inspires respect for his/her professional competencies

Finding a coach or a mentor

The best way of finding a coach or a mentor by far is personal recommendation. Failing that, you should consult bodies such as the International Coaching Federation, The UK College of Life Coaching, The Life Coaching Academy and The Industrial Societys School of Coaching. They should all be able to point you in a right direction when it comes to finding a reputable scheme or individual. It is worth noting that, because these are relatively new professions, a certain amount of caution should be exercised before allowing staff to divulge professional and personal information to a third party. Eventually, there will probably be a self-regulating code of practice similar to those in law or accounting.

Adapted from Benabou and Benabou, 2000 by permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

To summarise, coaching is a little bit like having the professional equivalent of a fitness trainer a specialist dedicated to working with you on specific goals and objectives you would like to achieve for whatever reasons. Mentors, on the other hand, are more likely to have followed a career path similar to the one on which you are embarking. They are, therefore, charged with passing on their knowledge and expertise. Importantly, the knowledge transmitted in this way will contain invaluable details about organisational values, beliefs and culture that are hard to acquire through formal training. Most definitions emphasise that the difference between coaching and mentoring is in the length of time they take but that is somewhat of a fallacy. Both are finite relationships, the average lifespan being six to eighteen months. Mentoring can develop into a friendship and, therefore, last much longer, but there are inherent dangers in blurring the role boundaries which are discussed later in this briefing.

Training

Although there probably are certain personality traits that predispose individuals to professions such as coaching or mentoring, the importance of training should not be underestimated. No-one is born a mentor a nurturing personality does not mean that you will be any good at running a mentoring scheme or coaching individuals. Mentors and coaches, like everyone else, require training, supervision and feedback. Finding a mentor as opposed to a coach is more problematic because the nature of the relationship is more personal. Some organisations adapt a laissez-faire attitude and leave it up to mentors and mentees to seek each other out, as it were. Some set up mandatory schemes where a third party usually someone from HR in consultation with line managers assigns individuals to senior members of staff who will act as mentors. The process is sometimes turned on its head reverse mentoring is where junior members of staff mentor senior managers, often on IT-related matters. When it works, the benefits of a structured approach are clear all the tacit, difficult-to-capture knowledge is

3

Mentoring and coaching parallels

As already mentioned, coaching and mentoring do share some common features. There could be occasions where coaches have to assume mentoring roles and vice versa. In most cases, they are both independent of line management relationships as that may stifle the openness and honesty which is or should be at the heart of a successful dialogue. A coach or a mentor in effect becomes an accountability partner working with your best interests in mind and bringing fresh insights to either specific tasks or your career or private life as a whole. Neither coaching nor mentoring is about teaching, instruction or being told what to do. As learning styles, their essence is facilitation. It should never be confused with simply giving advice or even feedback. Their role is to ask the right questions in order to generate individual self-awareness which can, in turn, lead to informed deci-

TECHNICAL BRIEFING

MENTORING AND COACHING

released and passed on to the next generation. However, there is a danger that such an interventionist approach could result in personality clashes that undermine the whole basis of a mentoring relationship. (See the article in Harvard Business Review, Nov/Dec 2000 entitled Too Old To Learn? about the perils of reverse mentoring. You can obtain the article through CIMAs Technical Advisory Service.) In either case, good preparation on both sides is crucial, as is an awareness of potential problems. Unfortunately, there has not been a plethora of studies on the best ways to match individuals in mentoring (and coaching) relationships. The little research that does exist seems to point to similarities between participants in beliefs, values and life goals. However, this attraction to like seems only to work at the level of general interests and background (whether social, cultural or educational). It does not mean that mentors and mentees need to have identical management or learning styles. Quite the opposite it seems that when this was the case, mentees soon lost interest as they perceived there was little new that could be learnt. Whatever matching approach you decide to take, make sure you meet the coach or the mentor before the process gets under way as good rapport between participants is essential. (This is somewhat less true for coaching as it is more about action planning and setting measurable objectives and less about learning by example.) With one-to-one mentoring, it is easy to establish early on whether sufficient empathy is present. Even on a corporate level, those in charge of setting up a mentoring or coaching scheme should consider how the potential candidate(s) fits in with the overall organisational culture and the individuals likely to be involved. Good rapport is also important because coaching and mentoring are powerful relationships that are open to abuse from both sides. The participants need to agree clear rules and boundaries before the process begins and stick to the same parameters throughout. Unless there is total trust, openness and commitment to confidentiality, the scheme will quite simply be unsuccessful. In addition, it should always be a voluntary programme no one should be coerced into being coached or mentored.

s s s s s s s

the incorrect matching of mentors/coaches and learners; the lack of top-down support; the resentment felt by those not involved in the scheme or the perception of favouritism; the creation of false promotional expectations; the overdependence of the mentor or mentee; gender issues; blurring of role boundaries and so on.

Reciprocity of relationships

It is worth remembering that rather than being one-sided, the best mentoring relationships are reciprocal. You dont simply turn up once a fortnight (or however often) and listen to some words of wisdom that will change your life forever. Both participants must play an active part, even though the onus is on the person being mentored or coached. A good coach or mentor will set tasks and objectives that need to be tackled before each meeting. It is then up to the individual to complete them, reflect upon them and try to apply them in practice. If there is no input, the coach or mentor might decide to terminate the relationship. A lot of popular literature on the subject focuses on the recipient of mentoring or coaching as if the relationship exists solely for their benefit. In fact, people choose to become coaches or mentors because they themselves get something out of it. Many would say that they enjoy being involved in someone elses development and that they enjoy nurturing young talent. Those who are managers themselves see it as a way of becoming better at their job by developing their listening skills and the ability to see things from a different perspective. Because it bypasses direct line management, mentees are more likely to be honest about their work problems and thus provide an invaluable insight into management roles. (The interaction between coaching and mentoring and management is discussed towards the end of this briefing.)

Feedback and performance measurement

Companies should ensure that there is a proper feedback mechanism at the end of any coaching or mentoring undertaken. This should enable an honest evaluation of its success or otherwise and provide the relevant information for any follow up action. Feedback should ideally be sought at regular intervals. This creates a timely opportunity to identify potential trouble spots and rectify any mistakes. Many coaches ask their clients to fill in questionnaires but feedback can also take the form of a discussion, formal or otherwise. It should involve the HR department or the scheme champion, if one has been appointed. There should be a report at the end detailing results and recommendations, based on the analysis of resources (including time and money) and participants feedback.

Barriers to effective coaching and mentoring

There is, as Long (1997) described it, a darker side of mentoring, despite the fact that most of the literature on the subject tends not to mention it. The majority of it concerns issues of organisational culture i.e. the context in which mentoring and coaching takes place and the interpersonal issues between the participants of the programme and the rest of the company. There is no space here to go into details of potential problems but some issues to bear in mind are (adapted from Ehrich and Hansford, 1999):

TECHNICAL BRIEFING

MENTORING AND COACHING

It is important that the usual constraints of structured planning and control are applied to coaching/mentoring schemes. Although it is more difficult to gauge success due to all the intangible factors involved (peoples perceptions, attitudes, etc.), some sort of performance measurement and costbenefit analysis is necessary. Companies should produce hard data whether qualitative or quantitative about the success or failure of the programme. There must be clear objectives from the outset, against which progress can be measured. Costs should be assessed during the implementation stage. Some companies link overall goals to a competency framework, with the annual performance rating of each mentee as a measure (Clutterbuck, 2000/01). Some compare costs of the mentoring programme to costs that would have been incurred using some other training activity to reach the same objective. Similarly, costs can be compared to the financial results of reaching a predefined target for example, saving achieved in reducing costs of conflicts (Benabou and Benabou, 2000).

Coca-Colas coaching programme, although less formal, is nevertheless structured through five different categories which provide a flexible approach for different situations. They are modelling, instructing, enhancing performance, problem solving and inspiration and support. Both coaching and mentoring are used as tools to support human resource development strategy and, therefore, the wider objectives of value generation within the company. They are thus directly linked to long-term corporate strategy.

Benefits of coaching and mentoring in organisations

Why have coaching and mentoring become so popular recently? Part of the answer surely lies in what the management guru Charles Handy once said would become the major challenge of our time managing individuals and not human resources. Companies like to say that people are their greatest asset but all too often as in Dilbert cartoons they slip to the ninth place behind carbon paper. To stem the flow of valuable intellectual capital, companies are trying to find new ways of retaining and motivating staff and thus increasing their productivity.

Setting up a mentoring or coaching programme

The mentoring and coaching programme in an organisation could be represented as consisting of the following phases:

Recruitment and retention

Coaching and mentoring can be a useful tool in recruitment and retention. Companies tend to spend a lot of money on anything from bottles of wine to full concierge services, forgetting that such incentives ultimately dont stop many people from moving on. What does is having interesting and fulfilling work to do and being treated as valuable individuals. By addressing personal as well as professional development needs and thus looking after the individual rather than the amorphous human resources coaching and mentoring can keep turnover rates in check. Staff feel valued and the management is clearly communicating its commitment to training and development. In a climate where internally-generated intellectual assets play a key role in creating competitive advantage, the bottom line will suffer unless you look after your staff.

Objectives and links to organisational strategy

"

Identification and matching of participants

"

Processes and systems needed to support mentoring or coaching

"

Evaluation and feedback

Companies adapt this basic programme to their own needs and objectives. A case study of Coca-Cola (Veale and Watchel, 1996), for example, showed that their mentoring programme follows a ten-point procedure outlined below: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. mentee identified; identifying developmental needs; identifying potential mentors; mentor/mentee matched; orientation for mentors and mentees; contracting; periodic meetings to execute the plan; period reports; conclusion; evaluation and follow up.

5

Continuous learning

Part of the reason for the surge in popularity also comes from our changing attitudes to work and learning. As mentioned at the beginning, lifelong learning has replaced the idea of one-off tuition. Coaching and mentoring, which can be undertaken at any stage in ones career, are perfectly suited to replace outdated learning styles. They can be adapted to all levels within a company from young managers seeking technical or specialised knowledge to senior executives requiring motivational training. CEOs in particular can benefit from having a coach or a mentor or both. Life can be lonely at the top, which is why it is helpful to have someone with whom you can talk without fear of embarrassment or appearing weak or indecisive.

TECHNICAL BRIEFING

MENTORING AND COACHING

Training versus mentoring and coaching

Companies are beginning to question the value of shortterm training programmes. They are designed to instil the company ethos in a relatively artificial environment and, therefore, frequently produce short-term benefits. The same scenario is probably repeated in thousands of offices throughout the country senior managers go off tree-hugging for a few days, come back full of enthusiasm and within five days things go back to normal. Mentoring and coaching because they focus on the individual and tend to be more long-term are capable of initiating a real change in behaviour rather than just rhetoric about it. They are not a substitute for training but should be used in conjunction with it. In Hales (1999) research about mentoring, mentees categorically denied that the outcomes could have been achieved through training alone. In fact, one US study showed that while training alone increases productivity by 22.8 per cent, for training combined with coaching the figure was nearly 90 per cent. Perhaps the skills acquired in this way could, as Hale suggests, be the bridge between training and implementation. They change peoples attitudes by addressing precisely the issues that normally act as barriers to putting newly acquired skills into practice such as confidence or risk-taking.

Of course, we are talking about successful schemes but there are plenty of opportunities for things to go wrong as we have already mentioned. From personality clashes to breaches of confidence, the consequences of a fallout are worth bearing in mind. There is no substitute for thorough initial preparation. There will always be those who are sceptical about the value of coaching and mentoring. Some equate it with therapy or counselling and are, therefore, suspicious about its appropriateness for the workplace. The truth is, they are nothing like therapy for one simple reason whereas therapy focuses on the past, coaching and mentoring are exclusively concerned with the future.

Links to good management

The aims of coaching and mentoring are essentially the same as those of good management. Both try to make the most of people. The characteristics of a good mentor can be narrowed down to the following (Hale, 1999):

s s s s

Soft skills acquisition

As mentioned at the beginning, many of the skills the finance professional of today needs are the so-called soft skills such as creativity, the ability to manage change, teamwork and so on. By their very nature, these are the skills that are difficult some would say impossible to teach in any kind of a formal training programme. This is where coaching and mentoring can be beneficial as part of the range of approaches used by organisations. In an interview for the forthcoming FMAC paper The role of the chief financial officer in 2010, John Connors, the Chief Financial Officer of Microsoft, said that CFOs will have to have more coaching in communication skills. They will have to become much more effective in framing their companys story consistent with the companys financial story. Finally, coaching and mentoring are actually cost-effective ways of making long-term changes in your organisations culture and operations. A study of Fortune 1000 companies who have implemented executive coaching showed that the average rate of return on investment was some 5.7 times the actual cost. For internal mentoring schemes, the figure is likely to be even higher.

listening, openness/self-disclosure; lateral thinking, challenging; bravery in involving the mentee in certain new work experiences; making time available; enthusiasm.

Clearly, these are not overly ambitious and should, in fact, be a part of every managers toolkit. Unfortunately, they very rarely are in practice. Some writers and practitioners go as far as to advocate that every manager should be a coach to his or her staff. The term management to them implies a command-andcontrol relationship unsuitable for a modern workplace flatter organisational structures demand more fluid working alliances. For example, Murphy (1995) calls for a general move from management to coaching. The so-called generative coaching is about understanding people in their wholeness and then acting on the basis of that understanding. The aim is to establish a mutual learning process where there is no one right mental model but there is enough space to consider various choices and possibilities.

Coaching style of management

One could in fact maintain that managers already possess the capacity to influence the performance and learning of others. Used actively, that can in itself be called coaching.

Adapted from Ehrich and Hansford, 1999

Benefits of mentoring programs

Mentee/protg Career advancement Personal support Learning and development Increased confidence Assistance and feedback New ideas Mentor Personal fulfilment Assistance on project Financial rewards Increased confidence Revitalised interest in work New ideas

Organisation Development of managers Increased commitment to the organisation Cost effectiveness Improved organisational communication Change management Leadership development

TECHNICAL BRIEFING

MENTORING AND COACHING

Its boundaries are likely to be narrower than where there is no direct line management crossover but there are nevertheless sizeable benefits. Being coached and being taught how to coach can demonstrate to young managers that looking after and nurturing your staff takes more than a quarterly team meeting and a pat on the back. It is no surprise that some managers are reluctant to adopt coaching into their management style. Because it requires total honesty and surrendering your personal agenda, it inevitably detracts from the mystique and importance of being a manager. A coaching style of management should be the adoption of a non-judgmental questioning method used to empower staff to reflect on their own actions and behaviour and therefore internalise any necessary changes. It is the opposite of the command and control paradigm which has been so prevalent in management. A part of every managers job, in other words, should be this facilitating process that consists of questioning, rather than instruction. There does, however, need to be a very clear distinction between a coach/mentor and a manager. If the line is blurred, coaching and mentoring can sabotage good management for example, a learner could feel that all the problems with his or her line management relationship can be taken to this independent third party. In reality, every member of staff should be able to voice their concerns to their manager and give him or her constructive criticism of their performance. Managing, then, should adopt features of coaching or mentoring but there should be no overlap in crucial areas. A coach or mentor, for example, is not there to give performance feedback, whereas appraisals should always be a part of the managers role.

organisation. Mentoring and coaching are used to strengthen the link between development and strategy through a threefold approach (Veale and Watchel, 1996): 1. to strengthen the link between business strategy and developmental focus; 2. to involve leadership of the organisation in all aspects of development; 3. to use a variety of developmental tools to match personal and organisational needs better. The lack of clear commitment from the top and the lack of conducive organisational culture can mean that even the best thought out schemes are destined to fail. In that case, coaching and mentoring become the latest fad to be artificially grafted onto the usual practices. Some organisations are simply not ready for it. For example, if there is nowhere to be promoted within the company despite the newly acquired skills and competencies, it is bound to result in frustration (Ehrich and Hansford, 1999). However, mentees expectations also need to be managed. It is a balancing act that can be achieved with sound planning and assessment. To conclude, mentoring and coaching can never be a panacea for organisations in trouble. They are simply two of the ways in which progressive companies tackle staff training and development.

References and further reading

s s s s s s s

Corporate strategy

To conclude, coaching and mentoring are not silver bullet or bolt-on solutions that will magically boost company morale or halt a haemorrhaging staff turnover. They should not be employed as reactive measures because they may mask the underlying problem rather than solve it. They need to be an integral part of the human resources strategy and, through that, the wider organisational strategy too, always aligned with corporate objectives. By tying in individual and organisational goals, coaching and mentoring can become strategic in nature. Correspondingly, they are capable of making strategy accessible by cascading it down to the level of individual concern. But they should never become a way of abdicating responsibility for good management or be used to impair line management relationships. For example, Coca-Cola Foods incorporates both coaching and mentoring in its human resources development effort. It perceives them as being the key to its competitive advantage and the creation of a high performing

7

www.coachingnetwork.org.uk www.executivecoaching.com www.indsoc.co.uk www.mentorsforum.co.uk www.mikethementor.co.uk/ www.lifecoachingacademy.com www.athena.ic.ac.uk/mentor.htm

Benabou, C and Benabou, R (2000), Establishing a formal mentoring programme for organisational success, National Productivity Review, USA, Vol 18, No 2. Bloch, S (1993), Business mentoring and coaching, Training and Development, Vol 11, No 4. Brockbank, A and Beech, N (1999), Guiding blight, People Management, Vol 5, No 9. Bruce, R (Ed), The role of the chief financial officer in 2010, FMAC draft. Clutterbuck, D (2000/01), Quiet transformation: the growing power of mentoring, Business Review, (Australia), Vol 3, No 2. Clutterbuck, D (2001), Mentoring and coaching at the top, Financial Times Mastering Management Survey, 8 January. Ehrich, L C and Hansford, B (1999), Mentoring: pros and cons for HRM, Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, Vol 37, No 3.

TECHNICAL BRIEFING

MENTORING AND COACHING

Flaherty, J (1999), Coaching: Evoking Excellence in Others, Boston: Butterworth Heinemann. Gregg, C (1999), Someone to look up to, Journal of Accountancy, (USA), Vol 188, No 5. Gross, R (1977), The Lifelong Learner, New York: Simon and Schuster. Guest, G (1999), Coaching for excellent performance, Training Journal, December. Hale, R (1999), The dynamics of mentoring relationships: towards an understanding of how mentoring supports learning, Continuing Professional Development, Issue 3. Hale, R: To match or to mis-match? The dynamics of mentoring as a route to personal and organisational learning on: www.bath.ac.uk/~edssjf/tomixormatch.htm Hegstad, C D (1999), Formal mentoring as a strategy for human resource development: a review of research, Human Resource Development Quarterly, Vol 10, No 4.

Long, J (1997), The dark side of mentoring, Australian Educational Research, Vol 24, No 2. Murphy, K (1995), Generative coaching: a surprising learning odyssey in Chawla, S and Renesch, J (Eds): Learning Organisations: Developing Cultures for Tomorrows Workplace, Portland, Oregon: Productivity Press. Thomas, A (2001), Coaching for success, Personnel Today. Veale, D J and Watchel, J M (1996), Mentoring and coaching as a part of human resource development strategy: an example at Coca-Cola Foods, Leadership and Organisational Development Journal, Vol 17, No 3. Zielinski, D (2000), Mentoring up, Training, (USA), Vol 37 No 10.

Other CIMA Technical Briefings on self-development

s s

Emotional Intelligence Leadership Skills An Overview

The Chartered Institute of Management Accountants 26 Chapter Street London SW1P 4NP Tel: +44 (0)20 7663 5441 Fax: +44 (0)20 8849 2468 www.cimaglobal.com

8

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Coaching and Mentoring StrategyDokument9 SeitenCoaching and Mentoring StrategybabajeeeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mentoring and CoachingDokument7 SeitenMentoring and CoachingkvijayasokNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coaching & Mentoring: Prepared By:-Narendra Singh ChaudharyDokument40 SeitenCoaching & Mentoring: Prepared By:-Narendra Singh ChaudharyApoorv Srivastava100% (1)

- Creating A Coaching and Mentoring Culture v2.0 June 2011Dokument6 SeitenCreating A Coaching and Mentoring Culture v2.0 June 2011Ion RusuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coaching and Mentoring: Knowledge SolutionsDokument5 SeitenCoaching and Mentoring: Knowledge SolutionsADB Knowledge Solutions100% (1)

- Coaching for High Performance: How to develop exceptional results through coachingVon EverandCoaching for High Performance: How to develop exceptional results through coachingBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (2)

- Implementing An Executive Coaching ProgrammeDokument19 SeitenImplementing An Executive Coaching ProgrammeGiagiovil100% (1)

- Measuring ROI in Executive Coaching by Phillips Phillips 2005Dokument12 SeitenMeasuring ROI in Executive Coaching by Phillips Phillips 2005John Dacanay100% (1)

- Coaching and MentoringDokument24 SeitenCoaching and MentoringDuraiD Khan100% (1)

- Coaching & Mentoring HandbookDokument36 SeitenCoaching & Mentoring HandbookMs J100% (1)

- Coaching and MentoringDokument5 SeitenCoaching and MentoringNashwa SaadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Principles of Coaching MentoringDokument25 SeitenPrinciples of Coaching Mentoringmind2008Noch keine Bewertungen

- CoachingDokument5 SeitenCoachingAnonymous xM7OgBgMbf100% (2)

- Coaching and MentoringDokument12 SeitenCoaching and MentoringIon RusuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coaching ModelsDokument20 SeitenCoaching ModelsSilver SandNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coaching Effectiveness Model Reveals Top Skills for SuccessDokument21 SeitenCoaching Effectiveness Model Reveals Top Skills for SuccessArcalimonNoch keine Bewertungen

- FYP Coaching Brochure ModlaDokument15 SeitenFYP Coaching Brochure ModlaModlaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Executive CoachingDokument60 SeitenExecutive CoachingCheri Ho83% (6)

- Coaching and Mentoring ManualDokument36 SeitenCoaching and Mentoring ManualAmey Joshi100% (13)

- 2019 Executive Coaching Survey Summary ReportDokument30 Seiten2019 Executive Coaching Survey Summary ReportEnrique Calatayud Pérez-manglano100% (1)

- Strategic Executive CoachingDokument5 SeitenStrategic Executive CoachingSimon Maryan100% (1)

- How Coaching Adds Value in Organisations - The Role of Individual Level OutcomesDokument17 SeitenHow Coaching Adds Value in Organisations - The Role of Individual Level OutcomesEsha ChaudharyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coaching and Mentoring Skills Training ManualDokument39 SeitenCoaching and Mentoring Skills Training Manualragcajun100% (2)

- Mentoring and Coaching in Organizations PDFDokument224 SeitenMentoring and Coaching in Organizations PDFdarwin88% (8)

- Reflective Practice For Coaches and Clients: An IntegratedDokument30 SeitenReflective Practice For Coaches and Clients: An Integratednemoo80 nemoo90Noch keine Bewertungen

- CoachingDokument61 SeitenCoachingرضا ابراهيمNoch keine Bewertungen

- Training Is Defined As The Process of Enhancing Efficiency and EffectivenessDokument53 SeitenTraining Is Defined As The Process of Enhancing Efficiency and EffectivenessManisha Gupta100% (1)

- Coaching Types: Origins, Applications & Regulation"TITLE"Guide to Coaching Styles: Life, Career, Executive & MoreDokument5 SeitenCoaching Types: Origins, Applications & Regulation"TITLE"Guide to Coaching Styles: Life, Career, Executive & MoreApai Tim Winrow100% (2)

- Coaching Knowledge AssessmentDokument13 SeitenCoaching Knowledge AssessmentSupreet SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Executive Coaching: A Conceptual Framework: Gaurav Sehra Vaka Lakshmi MeghnaDokument14 SeitenExecutive Coaching: A Conceptual Framework: Gaurav Sehra Vaka Lakshmi MeghnagauravNoch keine Bewertungen

- Here Is Team CoachingDokument20 SeitenHere Is Team CoachingfleurlotusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Successful CoachingDokument103 SeitenSuccessful CoachingGloria Cruz50% (2)

- Coaching Leadership EffectivenessDokument31 SeitenCoaching Leadership EffectivenessKathiravan KamalakaranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coaching and Mentoring Skill BuildingDokument60 SeitenCoaching and Mentoring Skill BuildingtrainbriteNoch keine Bewertungen

- CoachingDokument87 SeitenCoachingTimsy Dhingra100% (4)

- What Is Coaching? Answering Your QuestionsDokument5 SeitenWhat Is Coaching? Answering Your QuestionsKawtar Rossi El HassaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- 12 Step Roadmap Manager As Coach PDFDokument6 Seiten12 Step Roadmap Manager As Coach PDFالمدرب يوسف مغيزلNoch keine Bewertungen

- Implementing A Great Coaching and Mentoring ProgrammeDokument11 SeitenImplementing A Great Coaching and Mentoring ProgrammeATeamADED4F34100% (2)

- 4 Similarities and Differences Between Coaching and MentoringDokument5 Seiten4 Similarities and Differences Between Coaching and MentoringSyahnaz Alfariza100% (1)

- CoachingDokument115 SeitenCoachingsaralon100% (4)

- Mentoring at WorkDokument105 SeitenMentoring at WorkVan Boyo100% (4)

- 8521 Coaching SylesDokument32 Seiten8521 Coaching SylesJunaid AhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Case For CoachingDokument41 SeitenThe Case For CoachingFernando Cruz100% (1)

- Mentoring GuideDokument22 SeitenMentoring Guideapi-322485225Noch keine Bewertungen

- Coaching PholosophyDokument5 SeitenCoaching PholosophymoB0BNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coaching EssentialsDokument95 SeitenCoaching Essentialsgklim100% (4)

- Report Executive CoachingDokument21 SeitenReport Executive CoachingApoorva Singh100% (2)

- Premier Quality Assurance BodyDokument20 SeitenPremier Quality Assurance BodyMc MakhalimaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Submitted by Gursimran Singh Manchanda Harsimran Singh Karan Sudhendran Manoj Bharti MonicaDokument42 SeitenSubmitted by Gursimran Singh Manchanda Harsimran Singh Karan Sudhendran Manoj Bharti MonicaHarsimran SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leader As CoachDokument4 SeitenLeader As Coachkavya sharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Similarities and Differences in Coaching and MentoringDokument8 SeitenSimilarities and Differences in Coaching and MentoringMohammed HussienNoch keine Bewertungen

- CoachingDokument11 SeitenCoachingReginald KingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leadership Case Problem BDokument6 SeitenLeadership Case Problem Bapi-541748083Noch keine Bewertungen

- Mentoring in Action - David Megginson, David ClutterbuckDokument280 SeitenMentoring in Action - David Megginson, David ClutterbuckTahity100% (6)

- Coachinbg World ExtrasDokument40 SeitenCoachinbg World Extrasrichard_junior2100% (1)

- Management development techniques and identifying individual needsDokument7 SeitenManagement development techniques and identifying individual needsMuhammad OsamaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Executive Coaching: A Guide for the HR ProfessionalVon EverandExecutive Coaching: A Guide for the HR ProfessionalNoch keine Bewertungen

- It's Not About the Coach: Getting the Most From Coaching in Business, Sport and LifeVon EverandIt's Not About the Coach: Getting the Most From Coaching in Business, Sport and LifeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Self: Answering The Question "Who Am I?"Dokument4 SeitenThe Self: Answering The Question "Who Am I?"Lucas PadrãoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Learnenglish Elementary Podcasts S04e01 Transcript PDFDokument4 SeitenLearnenglish Elementary Podcasts S04e01 Transcript PDFLucas PadrãoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Content Thinking Through Music With 2013Dokument5 SeitenContent Thinking Through Music With 2013Lucas PadrãoNoch keine Bewertungen

- English Exercises: What Where Who When HowDokument2 SeitenEnglish Exercises: What Where Who When HowLucas PadrãoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Livro 01Dokument68 SeitenLivro 01Lucas PadrãoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Discoveries PDFDokument12 SeitenDiscoveries PDFLucas PadrãoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Baroque Terms PDFDokument5 SeitenBaroque Terms PDFmarkopranicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Informal Learning and ValuesDokument15 SeitenInformal Learning and ValuesLucas PadrãoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dunsby Whittall Music Analysis PP 103 130 PDFDokument32 SeitenDunsby Whittall Music Analysis PP 103 130 PDFLucas PadrãoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Railway Children PDFDokument41 SeitenThe Railway Children PDFomeomup80% (5)

- A Generative Theory of Tonal MusicDokument18 SeitenA Generative Theory of Tonal MusicLucas PadrãoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Temperley mts11Dokument23 SeitenTemperley mts11Leonardo AmaralNoch keine Bewertungen

- Searl 20th Century CounterpointDokument168 SeitenSearl 20th Century Counterpointregulocastro513091% (11)

- An Analytical Study: Applying Hindemith's Tonal Theory To Niels Viggo Bentzon's Third Piano Sonata, Op. 44Dokument62 SeitenAn Analytical Study: Applying Hindemith's Tonal Theory To Niels Viggo Bentzon's Third Piano Sonata, Op. 44Lucas PadrãoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complex TheoryDokument17 SeitenComplex TheoryDer DoppelgangerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Frankfurt SchoolDokument13 SeitenFrankfurt SchoolLucas Padrão100% (1)

- Verbs TensesDokument32 SeitenVerbs TensesLucas Padrão100% (1)

- An Analytical Study: Applying Hindemith's Tonal Theory To Niels Viggo Bentzon's Third Piano Sonata, Op. 44Dokument62 SeitenAn Analytical Study: Applying Hindemith's Tonal Theory To Niels Viggo Bentzon's Third Piano Sonata, Op. 44Lucas PadrãoNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Man Has Made of HimselfDokument275 SeitenWhat Man Has Made of HimselfLucas Padrão100% (2)

- Math Enrichment ResourcesDokument7 SeitenMath Enrichment ResourcesDushtu_HuloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Characters Lesson Plan Form-Completed by ErsDokument4 SeitenCharacters Lesson Plan Form-Completed by Ersapi-307547160Noch keine Bewertungen

- LE 1 - Speaking SkillsDokument10 SeitenLE 1 - Speaking SkillsmohanaaprkashNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reflection On Instructional LeadershipDokument1 SeiteReflection On Instructional LeadershipReynelyn BeltranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Week-2 BPPDokument3 SeitenWeek-2 BPPJen Ferrer100% (1)

- An Action Research On Classroom Teaching in English Medium: Renu Kumari Lama ThapaDokument10 SeitenAn Action Research On Classroom Teaching in English Medium: Renu Kumari Lama ThapaBhushan BondeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Angles of Elevation and Depression LessonDokument6 SeitenAngles of Elevation and Depression LessonNhics GarciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Igc1 Examiners Report Sept18 Final 020119Dokument14 SeitenIgc1 Examiners Report Sept18 Final 020119rnp2007123Noch keine Bewertungen

- Dartmouth Rassias MethodDokument24 SeitenDartmouth Rassias MethodZaira GonzalezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Charterhouse School, The Heritage TourDokument9 SeitenCharterhouse School, The Heritage TourFuzzy_Wood_PersonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bilingualism in Sri Lanka: Profiles of Diverse Language UsersDokument8 SeitenBilingualism in Sri Lanka: Profiles of Diverse Language UsersDeepthi SiriwardenaNoch keine Bewertungen

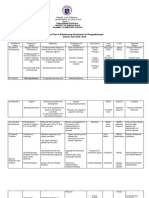

- Action Plan in EPP 2017 2018Dokument4 SeitenAction Plan in EPP 2017 2018marilouqdeguzman88% (16)

- Curriculum Development (Prelim)Dokument3 SeitenCurriculum Development (Prelim)daciel0% (1)

- Harmony PrayerDokument3 SeitenHarmony PrayerKen Sison0% (1)

- Dietz HenryDokument14 SeitenDietz HenryyauliyacuNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Pass The Civil Service Exam in The Philippines in One TakeDokument4 SeitenHow To Pass The Civil Service Exam in The Philippines in One TakeP.J. JulianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Using Drama in ELTDokument13 SeitenUsing Drama in ELTvedat398Noch keine Bewertungen

- Reflection On Mock InterviewDokument2 SeitenReflection On Mock Interviewapi-286351683Noch keine Bewertungen

- Analyzing the Spiral Curriculum and Content Needs in Araling PanlipunanDokument5 SeitenAnalyzing the Spiral Curriculum and Content Needs in Araling PanlipunanMarilou NavarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Canva for Education WorkshopDokument34 SeitenCanva for Education Workshopwareen cablaida100% (1)

- DO 27 S 2019 PDFDokument258 SeitenDO 27 S 2019 PDFEduardo O. BorrelNoch keine Bewertungen

- 12 Different Types of Leadership StylesDokument3 Seiten12 Different Types of Leadership StylesAli Atanan91% (11)

- Yvonne MooreDokument3 SeitenYvonne MoorearyonsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spera 2005Dokument22 SeitenSpera 2005lviNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prospectus 2007Dokument76 SeitenProspectus 2007skv_net6336Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2972 9345 1 PB PDFDokument3 Seiten2972 9345 1 PB PDFGordon ThompsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- QRT4 WEEK 2 TG Lesson 84Dokument5 SeitenQRT4 WEEK 2 TG Lesson 84Madonna Arit MatulacNoch keine Bewertungen

- Building Bridges-29 March 26 2014Dokument5 SeitenBuilding Bridges-29 March 26 2014api-246719434Noch keine Bewertungen

- Prof Ed Module 3Dokument31 SeitenProf Ed Module 3Paolo AlcoleaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ENGR371 Course OutlineDokument4 SeitenENGR371 Course OutlineCommissar CoproboNoch keine Bewertungen