Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Action Research

Hochgeladen von

rodickwh7080Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Action Research

Hochgeladen von

rodickwh7080Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Running Header: CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL

Culture in a Chinese Class in Brazil William Rodick George Mason University EDUC 606 Dr. Shanon Hardy March 2013

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL

Abstract An Hui Lee teaches Chinese to eleventh and twelfth grade students at an American school in Brazil. This study investigated interventions that sprang from a need to include culture into his course curriculum. An analysis of student, teacher, and school cultures provided a platform for greater understanding of what An Hui needed for increasing effectiveness in his classroom.

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL This study was conducted at an international school in Brazil, and while descriptions of the school, its students, the instructor, and culture are accurate, names and other identifying information, including the location of the school, have been changed. As curriculum coordinator and the evaluating administrator of An Hui Lee, helping the teacher work through a desire to understand aspects of his course better became a relevant and positive collaborative project for the study author. The puzzlement grew naturally from the evaluation process, and became an opportunity to consider curricular aims for the school. As an American school that hosts students from many nations, the question of incorporating culture into the curriculum effectively is a persistent one.

Setting

School and Educational Philosophies The American School of Metropolitan Florianopolis (ASMF), located in Florianopolis, Brazil, is an International Baccalaureate (IB) World School, with both the Primary Years Programme (PYP) and Middle Years Programme (MYP) complementing standards compiled from Common Core State Standards (CCSS), American Education Reaches Out (AERO), and Brazilian national standards (PCNs). The philosophy of the International Baccalaureate, its learner profile attributes, its emphasis on holistic learning, and its aim to build globally-minded, well-rounded students, runs throughout the curricular aims of the entire school, and into each classroom. Instruction at the school is given in English for our American program, and in Portuguese for our Brazilian program, and the school offers language courses in Spanish and Chinese. ASMF is a small, private school of about 240 students providing curriculum and instruction from pre-school to twelfth grade. Class sizes are increasingly smaller in middle and high school. The size of ASMF allows for greater

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL parental involvement than one might experience at a large public school in the U.S. At the same time, the size of the school does limit the availability of resources for students with special needs. There is an on-hand school psychologist, and because a large portion of the population is local, a full English as an Additional Language (EAL) department. The high school, which is comprised of eleventh and twelfth grades, is less rigidly structured than the IB programs that end in tenth grade. These students are additionally offered Advanced Placement courses and online courses through a partnership with K12, which creates greater flexibility in the curriculum. Many of the core subject teachers of eleventh and twelfth grades also teach MYP courses, but the majority of high school teachers are part-time. Cohesion is absent across subjects, but teachers are also given greater flexibility, mostly following their own curricular aims. During many observations of teachers, a consistent pattern has been noticed for Brazilian middle and high school instructors similar to what Herivelto Moreira found in a case study of Brazilian public school teachers: a) presentation of the content, previously selected by the teacher, b) resolution of one or more exercises, and c) proposition of a series of exercises for students to solve in classroom and at home. They exposed the content and asked students: Do you have any doubt? The students were not always willing to present their doubts, because they knew, from previous experiences, that this question was mere formality (Moreira, 2012, p. 64). The IB philosophy, which is wholly rooted in student-centered education, is a philosophical shift for many instructors of varying pedagogical backgrounds. However, during the two and a half years of which the school has been authorized to provide the IB Middle Years Programme, many Brazilian and foreign teachers have

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL shifted practice to incorporate IB philosophy. At the moment, the school is in a continually transformative state, where practice across all programs and grades is moving towards alignment around the IB framework of student-centered education. Classroom Chinese in the school is instructed by An Hui Lee, who teaches one course for eleventh grade and one course for twelfth grade. For teacher evaluation, An Hui Lee requested that I observe his eleventh grade class, which with ten students is the larger of the two classes. Four boys and five girls split the class. Seven of the students are Brazilian and the other two students originate from South Korea and Argentina. None of the students have studied Chinese in the past. The course is mandatory for students due to the structuring of the schedule, except for students who take online courses through our K12 service. One of the students is new to the course this semester, having been enrolled in K12 courses last semester. This course meets once per week Wednesdays from 7:45 to 9:15 a.m. Each of these class meetings is held in a classroom that is used by multiple teachers and courses throughout the week. Students do not have assigned seats, and the location of desks within the classroom is different depending on the way other teachers had previously wanted his or her desks to be arranged. However, the classroom is small, and desks are usually arranged in two rows facing a dry erase board. The Instructor Twelve years ago, An Hui Lee was living in Switzerland, having recently left the rural village in China where he had spent most of his life (Instructor Interview Notes Appendix A). In conversations with friends there, he became eager to continue traveling westward, and the destination frequently lauded in his circle was Brazil. An Hui explored the country for six months as a tourist before falling in love

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL with the country and its people. His friends, his environment, his sense of identity, have all been altered after living as a Chinese man in Brazil for more than a decade. An Huis higher education degree, which he earned while in Switzerland, is in hotel management, but he did not pursue work in this area when he moved to Brazil. For his first two years in Brazil, An Hui was employed as a ballet dancer. During these first years, he also recognized the value of his native language, and began teaching and translating. After a few years of teaching and translating, An Hui enrolled in an online degree for teaching Chinese as a second language. Among the topics covered, he studied Chinese culture, intercultural communication, Chinese language, classroom preparation, learner preparation, pronunciation, and lesson planning and instruction. An Hui Lee teaches full-time as a Chinese language instructor, contracting his services to businesses in the city who wish for their managerial staff to gain proficiency in Chinese as a direct result of Brazilian and Chinese expansion in the international business realm. He also teaches two courses at ASMF, expanding the schools language offerings to reflect that same growing internationalism. This is his third year teaching at ASMF, and since his work with the school is part-time, he does not get the opportunity to participate in professional development workshops, faculty meetings, or professional learning communities. Most of his professional interaction at the school is conducted through his evaluation process, which involves regular communication and meetings with the the schools curriculum coordinator. Language and Background The seven Brazilian students have Brazilian Portuguese as a primary language. These students are also proficient in English at varying levels. The South Korean student (JAH) has Korean as a primary language, but also speaks English and

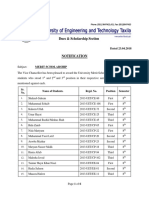

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL Brazilian Portuguese with limited proficiency. JAH is a special needs student, and only a few of his classes are mainstreamed. The Argentinian (AVM) student has Spanish as her primary language. She is fluent in English and Brazilian Portuguese. The school does not have a program for special education students, but there is a system in place for JAH, through which most of his instruction throughout multiple subjects takes place in one-on-one sessions with Mrs. Flvia Vermelho. Outside of this particular situation, the school does not have a system for identifying students with learning disabilities or emotional disturbances. Test Results and Literacy This year, the school is implementing the Northwest Evaluation Associations (NWEA) Measures of Academic Progress (MAP). The first test was given at the end of the first semester in December. The test coordinator did not include JAH in the testing. Student (Alias) SAP SIP ARM MEI FOB JEJ TAR OLI AVM Reading Score 230 216 220 229 240 231 237 243 244 Beginning of Year Mean Gr. 7 Beginning of Year Mean Gr. 8 Grade Level Equivalent Language Use Score 228 215 229 237 229 229 231 237 241 Grade Level Equivalent

Middle of Year Mean Gr. 6

Fig. 1. MAP Results: * indicates that the grade level equivalent is above end of year mean grade 11.

The majority of students exceeded the tests range for descriptive measurement. The results are only indicative of one test, and the MAP is created to

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL allow a school to test students multiple times to gather a collection of data points. Additionally, as this is based on one test, the results will need to be compared to other sources of data. Although this information regards English, it does give an indication about overall language development.

Puzzlements

Course Expectations The Chinese course at AMF is an elective course by nature, but given the size of the school, the structure of the schedule demands that all students within a grade level attend the same courses. As an international school, there was a desire to include languages in the curriculum for building a linguistic repertoire for our students (Administrator Interview Notes Appendix B). Internationally, Chinese is slowly becoming a major language for business, an area in which many of our students have previously expressed interest. Naturally, countries are responding by putting programs in place to create future leaders who can establish relationships with a country that is becoming increasingly involved in international relations. The 100,000 Strong Initiative is Barack Obamas response, which seeks to prepare the next generation of American experts on China who will be charged with managing the growing political, economic, and cultural ties between the United States and China (100,000 Strong). An Hui Lee has complete autonomy in the creation of his course, and in its fourth year, it continues to be impressive to hear students use a range of vocabulary, spoken through exceptional accents. The course thus far, as understood by the author from observations and meetings over the past year and a half, has essentially been language practice. An Hui Lee often uses worksheets, pair work, and speaking exercises, providing support consistently. He introduces vocabulary slowly, gives students the opportunity to practice that vocabulary in a variety of contexts, and often

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL tests student understanding in a variety of methods before the end of class (Classroom Observation Appendix C). His goals are often about students being able to speak comfortably in specific contexts. Considerations for Change At the start of this semester, there has been a community response, which often takes consistent form in small schools such as this one. Students approached the director of the school to express their concerns that the class was not helpful to them (Instructor Interview Notes Appendix A). Following the expression of these concerns, the director met with An Hui Lee to brainstorm ways to make the curriculum more interesting to the students. The result of this meeting was that the course should be inclusive of language and culture. As his evaluating administrator, An Hui Lee brought this to my attention. An Hui Lee seemed concerned that discussing his culture with the students poses two problems: he does not feel comfortable sharing his own feelings and background with the students, and he does not feel that he is representative of Chinese culture, having lived in Brazil for so many years. Curricular Evolution This is An Hui Lees fourth year teaching Chinese to students at ASMF. During his first two years, he taught very small classes of seniors, who used the language, but would often sleep or become distracted during class. During his third year with the school, he taught a junior class of about fifteen students. This particular group was aggressive in its social interactions, and students who spoke up in class could look forward to multiple abuses and jokes made on their behalf. All teachers had difficulty with classroom management of this group, and this led to compromised

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL learning goals. For each of these years, An Hui Lee aimed to expose students to vocabulary and push them to acquire minimal speaking proficiency. For this school year, An Hui Lee has a class of exemplary students, in the manner in which they behave and their dedication to their studies. Many of these students represent organizations like Model United Nations and National Honor Society, and only one or two are ever referred for behavioral issues. As independently driven, goal-oriented, and reflective young people, it seems fitting then that they are less engaged if they have difficulty seeing value in this course. Research Question There are many issues to address in this circumstance. Primarily, the student concerns about the course are not likely a conflict of curricular aims. Most students do not feel that Chinese will help them in the future (Survey Appendix D). The issue may not be with An Hui Lees course, but with taking a course that they did not decide was necessary for them. The opening of online courses through K12 most likely exacerbated this feeling. However, the director does wish to include culture as a part of the course (Administrator Interview Notes Appendix B). An Huis background is not in teaching, but he has now been teaching Chinese for eleven years in Brazil, and has been credentialed in that regard for seven years (Instructor Interview Notes Appendix A). To simply include an examination of Chinese culture would be artificial, especially given An Hui Lees concerns. This leaves us with the question, How can culture be studied in a Chinese course in a way that accommodates the complex cultures within a course? We must also consider how An Huis professional comfort and knowledge could impact the success of any attempt to include culture.

10

Framing the Issue

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL The focus of this puzzlement is a consideration of culture the culture that can be included in the curriculum, but also the cultural identities of the students and the teacher, and also the culture of the school and of the aspirations for students who have the financial backing to attend the school. Because of the many components involved in this study, a framework for action research guided the process. Cultural Inquiry Process The Cultural Inquiry Process (CIP) is a website and guide designed by Evelyn Jacob (1999) to provide resources and references that help educators improve education through action research that focuses on cultural influences upon students. Although pedagogical literature often highlights teaching methods, classroom management, and the particular learning processes of individual students, information about cultural influences on education are often general. Action research properly conducted can counter the potential that generalized information has for producing or reinforcing stereotypes, and action research can more sufficiently address a particular community, a particular group of students, or an individual. The seven steps of the CIP infuse culture into a process that echoes other action research guides. This process begins with selecting one or more students to focus upon and identifying a puzzlement. The action researcher must then consider what he or she already knows of the situation, and then must consider alternative cultural influences. This allows the researcher to question his or her assumptions, while forcing reflective analysis. The researcher then acquires and analyzes relevant information through the triangulation of data from multiple sources. This informs the research of an intervention to implement and monitor. At the end of the process, the teacher researcher arrives back at the start of the process with new understandings, and possibly, new puzzlements, cycling through a continuous process of inquiry.

11

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL Cultural Influences A question that seemed immediately relevant to this puzzlement concerned school culture: How might the school's culture be contributing to the puzzling situation? (CIP 3.2) (Jacob, 1999). School perception of student need and student perception of student need may be misaligned, and if this is the case, the inclusion of culture in the classroom has to be considerate of possible misalignment. An Hui Lee is open to incorporating culture in the classroom, but has some reservations about discussing his own culture in the classroom. He is also conflicted in how he may increase student engagement, and believes that an inclusion of culture in the curriculum may help. This leads to a consideration of the question, How might your beliefs or values, or those of other educators, be contributing to the puzzling situation? (CIP 3.1) (Jacob, 1999). The instructor must overcome previous beliefs about the instructor and student relationship if his plan will be successful. The students do not see a direct need for themselves to learn Chinese (Survey Appendix D), and if the importance of this course contrasts with the perception students and their parents have for what is important in the curriculum, then it may be difficult to engage student learning: How might mismatches between a student's or group's home culture(s) and the school curriculum be contributing to the puzzling situation? (CIP 3.3.2) (Jacob, 1999).

12

Literature Review

Origin of Understanding An Hui Lees class is a composite of students and an instructor all capable of operating between languages, and as such, there are foundational understandings that language and culture work in synchronicity, yet this perception does not extend to Chinese. It is likely that this is because the idea of what it is to be Chinese is foreign

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL to these students. In order to break down the wall that is student misperception, there must be an integration of Chinese culture within the curriculum. For a goal of translingual and transcultural competence, students learn to reflect on the world and themselves through another language and culture (Byrnes, 2008, p. 289). A clear understanding of student perceptions has to be gleaned first before learning goals, or the direction of cultural integration, can be determined. This can be accomplished while examining the culture of instruction. An Hui Lee learned language as a student far differently than the students sitting in his classroom. There are vastly different life experiences, cultural influences, and aspects of social dynamics between An Hui Lee and his students: If the way we were taught is significantly different from that of the students we are teaching, much of what we may view to be of value in the learning of a given language may be at best irrelevant and at worst useless (McGinnis, 1994, p. 17). As we enter an alteration of curriculum to assist students in learning a language by packaging that learning in the truer conceptions of target language culture, we first have to have an understanding of our own misconceptions and disconnects, be they with the students themselves, the languages and cultures of those students, ideas about how language learning best functions, or perceptions of the target language and culture. It will be important to examine the perceptions of the instructor and of the students as a method for developing goals for the course linguistic and cultural goals. Methods Wenli Tsou (2005) conducted a study of American culture integration for Taiwanese students learning English. A motivation for that study was that many [foreign language] classrooms still view culture learning as an addendum to language

13

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL study and deal mostly with food, festivals, buildings and other cultural institutions [] culture still stands for a small percentage in the foreign language-teaching curriculum (p. 40). The same is true for An Hui Lees classroom, where the current emphasis of instruction is entirely language-based. The goal for Tsou and his research team is acculturation where culture is not simply a lesson or a study of text, but consistent cycle of awareness of culture the culture of oneself and the cultures of others. There were two major instructional components of the Tsou study a comparison of both home and foreign cultures, and an exploration of foreign culture through storytelling. An Hui Lee has indicated that his students are more engaged when he provides them with interesting stories that shock his students about Chinese culture, which they then discuss further in contrast with western cultures. He mentioned the eating of dog as an example. Although he knows that very few people eat dogs in China, he also knows this is something that will stimulate student discussion. An Hui Lee also recognizes however, that culture is far more complex than the shocking stories that currently engage the students from time to time. In one of our conversations, he compared experiencing a new culture to a marriage, and then to an iceberg: we believe we understand it and that we can know what to expect from this surface level perspective that we initially have, but there is far more beneath the surface than we can fully realize (Instructor Interview Notes Appendix A). One goal here is to make his conversations about Chinese culture in the classroom more like the expansive substance of ice that exists beneath the surface. Tsou (2005) stresses that teachers must first guide students through the seeking of similarities before examining differences between learners native and target cultures. To do otherwise may

14

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL reinforce stereotypes and distance students from empathizing with the target languages culture. This is certainly the case for An Hui Lees story about dog eating. An Hui Lee has not eaten dog, and recognizes that few Chinese do. He is not introducing students to Chinese culture, but to a stereotype. It would be helpful for An Hui Lee to first gather an understanding of what students know about Chinese culture, so that he can navigate how to introduce similarities that will provide a window to empathetic cultural study. It is from this basis that he can also determine, along with the students, cultural and language goals for the course. Tsous (2005) study also relied on an ever involving narrative about a boy named Joe, who was a Taiwanese boy learning English while living in San Francisco. This story allowed the teachers to create a story that could incorporate cultural and linguistic aspects of teaching as they were introduced in the class, while allowing students a method for interacting with culture vicariously through Joe and his experiences. Storytelling allows students to interact with context. Another method for context integration is the use of images: If students are trained to look at images with a new, more inquiring eye and to dig down below the surface to identify and describe manifestations of possible cultural perspectives that are ultimately part of a larger cultural narrative rather than just seeing them as decorative elements on a page, a bulleting board, or a Web site, this in itself is a significant first step toward entering an extended interaction of language and culture (Barnes-Karol & Broner, 2010, p. 440).

15

Methodology

Survey

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL Collection A survey, which could be created by combining open-ended and close-ended questions, seemed an ideal method for collecting honest and direct responses from students. The survey composed of five major sections: The Classroom and Its Operation, Background, Future, Present, and The Teacher and the Course (Survey Appendix D). To encourage honest answers from students, the following was included atop the survey: Please take a few minutes to answer the following questions honestly. Your responses will have no bearing on your grade, nor will they be the basis for any judgment of you as an individual, as a student, as a member of the school community, or in any other possible capacity. The information in this survey will be used explicitly to inform strategies for making your learning experience the best it can possibly be. Questions in the section titled, The Classroom and Its Operation, asked students for responses that would reflect both a cultural perspective of how a society best functions and of how a classroom best functions. The GLOBE Project (Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness Project) is a study that saw 170 voluntary collaborators collect data from about 17,000 managers in 951 organizations in 62 societies throughout the world (Hofstede, 2006). This major crosscultural examination relied on surveys as a basis, and these surveys collected information about the ways in which leadership, culture, and organization function across and within segments of the world. By using the GLOBE Project as a model, the survey created for An Hui Lee and his students could gain a similar perspective of cultural connections to leadership, culture, and organization within a classroom. Not all of the GLOBE Project questions fit this purpose; the question, In this organization, physically demanding tasks are usually performed by men or women?

16

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL cannot be modified to suit the classroom, and any modification would not likely result in information that would reveal cultural assumptions in the classroom (a more suitable question about men and women was included in this questions stead) (GLOBE, 2006, p. 7). The SAGE Leadership: Theory and Practice text modifies the GLOBE study survey to more distinctly address dimensions of culture, and so the language of this adapted survey was also used in the creation of questions for The Classroom and Its Operation. Questions in the Background section of the survey were modeled from one section of the Cultural Perspectives Questionnaire (CPQ) created by the International Institute for Management Development (IMD), a top business school located in Lausanne, Switzerland. Two of the research goals attached to the CPQ are to describe to leaders how cultural similarities and differences affect work in organizations, and how individuals can better understand and communicate with other people within other cultures (IMD, 2013). Questions in the Future section of the class survey ask students to consider their career, their interests, and the impact of current schooling on those goals. An Hui revealed through interview that the junior class that was most difficult from the previous school year did respond once they could see a connection between their business aspirations and Chinese language knowledge. This section aims to discover if a similar correlation could benefit this course. Questions in the Present section aimed to discover how students perceived their Chinese course in relationship with other courses, and to discover quick impressions of their thoughts on Chinese culture and language. Questions in the section titled, The Teacher and the Course are the very questions that make up the student survey that is a requirement for all teachers in the

17

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL schools evaluation system. These questions are a great complement, as they ask direct questions about the teacher and the class. Analysis Once completed, the survey was sent to students and the instructor. This provided an opportunity for comparison. In many ways, the survey results demonstrated commonality in perceptions of classroom organization and systemic cultural beliefs. Both the instructor and the students believe that it is important for students to question the teacher when there is disagreement (although An Hui mentioned in an interview that he believes a cultural difference is that teachers are not viewed as respectfully in Brazil), that learning requires a balance of collective and individual growth, that boys and girls are encouraged similarly, that students should be encouraged to strive for improvement, and that students should be rewarded for excellence. The students and An Hui disagreed about the role of grading and reward systems: students stated that a balance of individual and collective growth is maximized through the use of rewards, and An Hui stated that individual growth is maximized. However, An Hui spoke about this question after completing the survey, and was uncertain about his answer, leaning more towards the balance agreed upon by the students. While strongly agreeing that AMF will increase opportunity for working in a dream career, and that any such dream career will require multilingual ability, most students disagree that Chinese will help in that future career. In the section asking for the first three words respondents could relate to Chinese culture, Chinese language, and Chinese class, the most frequently repeated words were different, difficult, and boring, followed closely by interesting and hard. However, in most cases, words like hard and difficult were combined

18

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL with words of neutral or positive connotation, such as interesting, awesome, and funny. Only two students out of the seven responded with unquestionable negativity, and these two students remained consistently negative when referring to culture, language, and the class.

19

Fig. 2: World cloud of survey results

The ranking of courses in the Present section of the survey did not provide accurate data. It appeared that some students thought the values of 1 to 14 were a scale, and of those students, some thought that 1 was positive, while others thought that 14 was positive. The only information that could be gathered for certainty is that two of the seven students felt ambiguous about the courses importance.

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL

20

Fig. 3. Survey results - the importance of Chinese class

The survey provided targeted information about CIP 3.2: How might the school's culture be contributing to the puzzling situation? (Jacob, 1999). As the Chinese course is standard and required for all students, and administration has indicated that this course is highly valuable in extending the intercultural aims of the school, its importance as an aspect of school culture is evident; students, however, have indicated that the course is not as importance as an aspect of their learning culture. This also connects to CIP 3.3.2: How might mismatches between a student's or group's home culture(s) and the school curriculum be contributing to the puzzling situation? (Jacob, 1999).

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL In many ways, the instructors values and beliefs regarding the classroom, how it functions, and its expectations align with those of his students, indicating that CIP 3.1 may not be as important as initially believed: How might your beliefs or values, or those of other educators, be contributing to the puzzling situation? (Jacob, 1999). However, his enthusiasm and appreciation for Chinese culture is not matched by his students, who see the course, culture, and language as difficult and boring. Classroom Observation Collection While the survey provided opportunity to compare instructor and student perceptions of the course and gathered insight about student beliefs, this information needed to be examined through alternate lenses. What surveys cannot do is allow us to study nonverbal behavior (Abowitz & Toole, 2010, p. 7). The classroom observation provides an opportunity to cross-reference the behaviors and attitudes expressed in the survey. This observation was expected, and the instructor developed learning goals in a meeting in advance. The observation is a part of the teachers evaluation, but the instructor designed the lesson in consideration of this action research project. Analysis It was clear through the observation that an inclusion of culture, and the sense that students may benefit from applicability of the lessons was on An Huis mind. The lesson focused on learning and practicing the use of numbers through the context of sharing and using telephone numbers. At the start of class, An Hui incorporated a spontaneous mini-lesson, in which he gave a student her Chinese name, drew the characters, and explained the meaning behind each portion of the characters. In another part of the class, An Hui had chosen other language characters for students to

21

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL examine, and he chose characters that he believed would interest the students, such as the character that means study, which is made up of a character for claw that hovers above the character for son. An Hui also included questions throughout the lesson that forced cultural connections between China and Brazil. For the number six in Portuguese, Brazilians say, meia, which also means half (Why is it that they say meia meia and not seis seis?) He had been aware that the belief is that half is used because six is half of a dozen, and he used this question to force students to consider peculiarities of Chinese language from the perspective of the peculiarities of Portuguese. An Hui has students engage with learning in individual and group work, and during these moments, he walks around the room to guide students. He often asked questions in these interactions, and provided group members the opportunity to clarify misunderstandings before intervening. All students seemed engaged during this time, until his presence with one group lasted for about seven minutes. During this time, other groups finished work and became distracted, gossiping, texting on their phones, and laying their heads on their desks. This particular portion of the class seemed relevant to CIP 3.1: How might your beliefs or values, or those of other educators, be contributing to the puzzling situation? (Jacob, 1999). An Hui Lee stated during an interview that he believes Brazilian students have exhibit less deference and respect for teachers than Chinese students, yet in this circumstance, he did not extend that belief into compensating action during his teaching (Instructor Interview Notes Appendix A). If An Hui Lee has this belief, perhaps it is something for him to analyze to ensure that he is not relying on a stereotype. Then, if the particularities are evident in this class of students, which may have been the case in this observation, he has to alter his teaching accordingly to suit the culture of this particular classroom,

22

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL especially if his teaching suits the culture of classrooms he studied in as a boy in China. Instructor Interviews Collection Two instructor interviews attempted to gain information about teacher beliefs, student culture, school culture, and curricular aims. The first interview was exploratory, so that a greater understanding of the cultural issues at hand could be discovered. The second interview was focused around An Hui Lees background as a teacher, to gain a greater understanding of how teaching beliefs may influence cultural issues in the classroom. Analysis The interview revealed that although An Hui is Chinese, his identity is largely influenced by Brazilian culture. There is a lot of similarity between An Huis beliefs and values and those of his students. The instructor directly stated that he believes he may be becoming more Brazilian than he ever was Chinese. He also revealed some aspects of his beliefs and values that are fundamentally Chinese, particularly when he discussed the relationship between a student and an instructor in the classroom. In China, the teacher is revered, and students listen to the teacher without question. This is a sharp contrast to the relationship he has had with students here, and he does not create a classroom environment that forces students to obey the teacher without question (evident in his classroom observation, during which he encourages students to ask him questions). Past students have actually been overly disrespectful of An Hui, which was difficult for him to manage from a personal and cultural point of view. He also recognizes that teachers in this school are very open about themselves, informally interacting with students before and between classes. This is not a relationship that An

23

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL Hui recognizes as appropriate, because this is not the classroom he studied in as a child. He believes that by revealing more of himself may help him incorporate culture into his class, and incorporating culture may increase engagement. Administrator Interview Collection To discover information about the decision to include the course in the curriculum from the start, and the decision to now incorporate culture into the Chinese course, the director of the school was interviewed. Analysis The director stated that the course was created to include variety in the course curriculum and to extend language offerings at the school. These aspects of curriculum inclusion are associated with the internationalism of the school. She also stated that the decision to include culture in the classroom had always been the idea for the course, and that this echoes the idea of intercultural awareness, which is foundational in IB philosophy. She believes that the language also offers potential for students, as it is increasingly an important language for business. Not many of the students in this particular class plan to pursue a career in business, and they do not see relevance of the language to their career goals (Survey Appendix D); however, this idea is in line with previous classes of students at the school and An Hui Lee believes that company managers in Brazil are incorrect to believe that English is enough for international business, and that Chinese managers speak English. He emphasized that this is a misperception, and that many Chinese managers do not speak English, which means international representatives need to know Chinese in order to conduct business (Instructor Interview Appendix B).

24

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL

How can An Hui Lee teach culture in a way that benefits and considers the cultures of his students?

1. How might your beliefs or values, or those of other educators, be contributing to the puzzling situation? (CIP 3.1) 2. How might the school's culture be contributing to the puzzling situation? (CIP 3.2) Student Survey Instructor Interview Teacher Survey Classroom Observation Administrator Interview Student Interview

25

3. How might mismatches between a student's or group's home culture(s) and the school curriculum be contributing to the puzzling situation? (CIP 3.3.2) Fig. 4. Data Sources Matrix

Summary When looked at collectively, the information from these sources indicates that there is a disconnect between the cultural beliefs of the school and that of the students, and there is a mismatch between home culture importance and school curricular importance. There is also room for the instructor to consider the cultural beliefs that may impair his effectiveness in instructing this group of students.

Intervention and Monitoring

The instructor can identify with students in many ways, and although there does seem to be cultural differences between him and his students, An Hui Lee may not be able to define these differences. He may need to have a greater understanding of how culture influences his teaching before he can determine how to effectively alter his teaching in response. Additionally, there are instructional peculiarities that he can then better understand, which could be followed up with particular guidance in

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL the evaluation system. While no change can be made about the inclusion of the Chinese class, even if students see it as less important, instruction can help students see value for themselves in the course. Students do not see extreme value of the course or the language, and there is certainly a divide between the purposes seen by students and the school in curricular decisions. Intervention Teacher Perception McGinnis (1994) quotes the axiom, You teach the way you were taught. This is particularly relevant to An Hui Lee and his students. It is evident that in many ways, his native culture has been shaped by his Brazilian experience, but as a teacher whose training has been online without practicum in the classroom, he may incorporate the type of teaching he experienced as a student in his own teaching. Some of the ideas of that experience are evident in his current beliefs. It is important for Lee to consider what he knows about students in comparison to what he thinks he knows about students. For this circumstance, it will be necessary for An Hui Lee to reflect upon his own perceptions of the class and his teaching with the students survey results as a foundation. For the first part of this intervention, I will review the survey results with Lee, and ask that he write a reflection that addresses how he may have perceptions of the class, the students, and himself that could be explored and altered. An Hui Lee may not have a complete understanding of student perception of Chinese culture. They are intrigued and shocked by stereotyping stories, which indicates that they may have a limited understanding of the culture, viewing it as strange, and unable to see it as a reflection of themselves and their cultures. According to Tsou (2005), correcting these misperceptions of culture is an essential

26

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL basis for including true cultural study in a classroom. It will be important for An Hui Lee to first understand what those misperceptions may be. Student Perception Heidi Byrnes (2008) argues that language study has to be placed within a cultural framework and that curricula should be integrated around explicit, principled, educational goals. The students of An Hui Lees course have not previously studied culture explicitly and do not all see the value of the course in their learning. Student reflection, that incorporates a quest for finding personal value for the course (which would not necessarily need to be immediate), which could serve as a basis for creating class goals around the inclusion of culture, may provide students with greater ownership of the curriculum a curriculum that is unrestricted and can easily be molded to student interest and need. Lesson Elements Tsou (2005) argues that culture inclusion requires a consistent cycle of cultural awareness the culture of oneself and the cultures of others. It will be important for An Hui to include not just Chinese culture into the classroom, but to include questions about culture in general in the classroom, to provide students the opportunity to consider the flexibility of their own cultures in light of other cultures. Tsous study depended on teacher use of a consistent and growing narrative of a Taiwanese boy attending school in California (the study was about including American culture in an English course for Taiwanese students). Students were able to identify with the protagonist, and could perceive American culture from his fictional perspective. The narratives provided context for the language lessons, blending language curricular aims with cultural curricular aims.

27

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL Barnes-Karol and Broner (2010) also recognize the importance of context in meshing linguistic and cultural teaching. The authors used content-rich images to contextualize course readings. These images served as springboards for exploring perspectives. An Hui Lee expressed at the start of this process that he is not comfortable discussing his own life experiences and culture with students, but expressing these ideas through narratives, perhaps of friends or a fictional character, could bypass this cultural roadblock while also allowing for greater complexity than his current method of telling stereotyping, shocking stories. The incorporation of images, which then serve as a basis for discussing language lessons and culture, can serve as complements to narratives that allow students to recognize the commonalities of various cultures. Monitoring Instructor Meetings One aspect of the teacher evaluation system is that the instructor and evaluator meet to discuss lesson plans. I will meet with An Hui Lee to review the data I have compiled and discuss the possible interventions. In these meetings, I will assist An Hui in considering how to implement the interventions concretely in his plans for two weeks. The meetings themselves will indicate how successful the interventions may be. In the first of these meetings, I will also introduce the idea of cultural reflection. An Hui Lee will write a reflection in this meeting, and once again after the two classes he will teach in these two weeks. Observation

28

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL In his class, he will need to discuss with students their perceptions of Chinese culture. This and the inclusion of narrative and images to contextualize language teaching will require my observation. Student Feedback At the end of the second of the two classes I will observe, I will ask that each student complete a short questionnaire about their perceptions of the class and the value that it has for them. It is expected that the results will indicate growth in their beliefs about the value of the course.

29

Conclusions and Implications

Conclusions Initial monitoring shows that the need for intervention is even greater than first believed. During the first class in which interventions were implemented, an issue that An Hui Lee had with a student FOB highlighted the issues of cultural blockades and student disinterest (Instructor Interview Notes Appendix A). The incident itself was minor the student was using her computer, and An Hui asked her not to use her computer. It is unclear the phrases that were used to cause the confusion, but the instructor had wanted the student to put her computer away completely, and the student believed she had complied with his instructions by no longer using her computer and keeping it open. An Hui Lee is fluent in Portuguese and English, so while the consideration could be that this is a language barrier issue, the same issue could have arisen between any student and teacher. This seems more reflective of the underlying cultural distances in the class that the interventions are designed to help An Hui Lee traverse. The discussion that he and FOB had after class about the situation makes this clearer. During that discussion, FOB expressed the reasons for her disinterest. She

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL cannot see a need for learning Chinese. In response, An Hui Lee may have expressed a side of himself that is entirely cultural, and not necessarily controllable: he told her it is her duty to pay attention in the class, whether it is what she wants to do or not. This idea of a sense of duty and reverence for a course and the instructor, even when the student does not see value in the course, is a trademark of Chinese culture that An Hui Lee expressed in an earlier interview. An Hui Lee also strongly believes that it is his responsibility to make the class interesting and engaging for the students, and this dichotomy of his beliefs about classroom culture seems to be a perfect blend of his evolving and fluid culture. This makes it all the more important that he becomes aware of how the many parts of that evolving culture impact his class and his students. I asked An Hui Lee to base the initial intervention his own reflection of the culture of himself and his students on this incident, which so perfectly captures the many elements of this study. As McGinnis (1994) concludes, Identification of conflicts in the cultures of instruction of a language learning/teaching population can do much to improve the students total language learning process. Equally compelling, it provides a means by which the instructional staff may better come to understand their own conceptions and misconceptions as to what works and what does not work for their students (p. 21.). This class also allowed An Hui Lee to present another vital component of the interventions we outlined using cultural discussion as a basis for creating student learning goals. This is to address student perception of Chinese culture, which they largely viewed through the lens of stereotyping, and to give students an opportunity for personal investment in the course. Students discussed stereotypes of Chinese culture, including censorship of the government an aspect prompted by a student. Other students then responded in ways that broke

30

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL that stereotype down by providing anecdotes and context one said she has a friend in China with whom she interacts online, another said they know someone in China who uses Facebook, and another shared a story about Mark Zuckerberg visiting China. They then discussed perceptions of Brazil. Lee asked the Argentine student, AVM, if she had any false perceptions of Brazil before she arrived, and she shared how the idea is that Brazil is all jungle with little infrastructure. This discussion allowed students to reflect on the ease with which we develop misconceptions that are largely based on ignorance. It is from here that An Hui Lee asked students to consider the things they would like to know about Chinese culture and language. Students shared that they would like to learn about travel in China, colors, body parts, and sports. Part of my discussion with Lee was that the topics will help engage them to some extent, but the idea would be to have them develop goals for their learning, and I provided him with the example: I want to learn the vocabulary that would help me interact with shopkeepers while traveling in Brazil. and I would like to understand customs for interacting with a family so that I am not accidentally offensive. This misunderstanding of learning goals and learning topics will have to be addressed in future classes in order for this aspect of the intervention to be successful. An Hui Lee will be introducing images and stories as backdrops for teaching about travel the area of learning for which students expressed interest. An Hui Lee developed ideas for including this in his next lesson he would like to have students role play as though they are traveling in China. We discussed how this would connect culture and the teaching of language, and considered providing necessary scripts or vocabulary lists of the words he will teach after the role playing (or before), and setting the role playing in multiple cities, so that

31

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL students can recognize nuances of culture that exist between the many, diverse regions of China. Implications By taking into consideration the interests of students, and providing them with a cultural context that can serve as a basis for language teaching, An Hui Lee should do well to increase engagement and interest in his course. There is no question that Lee is learning about his own teaching through this process, as he gains recognition of the importance that consideration of culture plays in introducing culture in a classroom. An extension of increased student engagement and teacher reflectiveness is the impact this will have in other classrooms and for other teachers. Although An Hui Lee does not have much interaction with other teachers, the students certainly do. What expectations might students have when they recognize the changes that can arise from having a teacher asks them what they would like out of the course? Barnes-Karol and Broner (2010) observe the possibilities of cultural inclusion as they note that opportunities to open the door onto another culture surround us, and if we start to systematically take advantage of them, we can increase the culture learning in our classrooms and start to prepare students to be more culturally observant as they interact in the world beyond the classroom (p. 441). This is what this study is attempting, and I believe this process matches the continuous evolution of the school as it becomes more student-centered. The implication for An Hui Lee as a teacher continues through his evaluation process, of which this study is one component. Although the practice of reflection and change can be humbling, it is hopefully also very rewarding, and

32

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL what Lee has been able to learn about himself as a teacher will carry with him as he plans and interacts for next years Chinese students.

33

Reflection

This project addresses culture in the classroom from two fundamental perspectives that I had not considered before, even as a teacher who has lived and taught in four different overseas schools culture included as a curricular element and cultural consideration of the teacher and the students. By conducting this research alongside a teacher, it also forced me to consider the culture that teachers bring with them that influence their practice, their openness to new ideas, and their ability to adapt new practices. While Jacob (1996) found that the Cultural Inquiry Process can broaden teachers understandings of students from diverse cultural backgrounds, I would add that it can broaden teacher understanding of even those students with whom we already share aspects of culture (Jacob, et al., 1996, p. 35). Although An Hui Lee has now lived in Brazil for longer than he lived in China, and he is aware that much of his identity is informed by Brazilian culture, he needed to consider his classroom through the Cultural Inquiry Process in order to understand areas of cultural friction. Additionally, the process makes it evident that culture cannot be defined by location, country, or identity, but by an amalgam of influences, including financial background, moral influence, or acculturation through other influences. For example, An Hui Lees response to FOBs dislike of the course, in which he stated that being responsible in the class is her duty, is echoed in Brazilian classrooms everywhere, but FOB rejects this notion, which could be the result of her time in ASF rather than a component of national identity - a philosophy of

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL student choice and interest has been put in place during the entire time she has been enrolled at ASF. This study emphasizes the importance of cultural consideration in the classroom. From what I have observed as the Dean of Students at ASF regarding teacher issues with students, disagreements are often about much more than a misuse of technology, disrespect of classroom rules, or laziness. Although this does not diminish the responsibility of students within a classroom, it does shed light on how cultural misconceptions can exist at the root of student misbehavior and student mislearning. As an administrator, I have to consider the blockades that may exist between me and a teacher, through cultural identity as a person and cultural influence on pedagogical beliefs. As a teacher, I have to consider how my beliefs about student learning will always be shaped my own experiences and culture, and how these could be conflicting with the beliefs and abilities of students.

34

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL References 100,000 Strong Initiative. (n.d.). U.S. Department of State. Retrieved February 3, 2013, from http://www.state.gov/p/eap/regional/100000_strong/index.htm Barnes-Karol, G., & Broner, M. (2010). Using images as springboards to teach cultural perspectives in light of the ideals of the MLA report. Foreign Language Annals, 43(3), 422-445. Byrnes, H. (2008). Perspectives. The Modern Language Journal, 92(ii), 284-312. Cultural Perspectives Questionnaire - CPQ Project (2013). IMD Business School. Retrieved February 4, 2013, from http://www.imd.org/research/projects/CPQ.cfm GLOBE (2006). Research Survey. GLOBE Project. The GLOBE Foundation. Hofstede, G. (2006). What did GLOBE really measure? Researchers' minds versus respondents' minds. Journal of International Business Studies, 37, 882-896. Jacob, E. (1999). Cultural Inquiry Process. George Mason University Classweb. Retrieved March 17, 2013, from http://classweb.gmu.edu/cip/ Jacob, E., Johnson, B., Finley, J., Gurski, J., & Lavine, R. (1996). One student at a time: The cultural inquiry process. Middle School Journal, 37, 29-35. McGinnis, S. (1994). Cultures of instruction: Identifying and resolving conflicts. Theory Into Practice, 33(1), 16-22. Moreira, H. (2012). Understanding teachers' knowledge: a case study in Brazil. International Journal of Education, 4 (1), 50-67. Northouse, P. (2013). Leadership: theory and practice (6th ed.). Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage. Tsou, W. (2005). The effects of cultural instruction on foreign language learning. Regional Language Centre Journal , 36(1), 39-57.

35

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL Appendix Table of Contents

36

A. Instructor Interview Notes B. Administrator Interview Notes C. Classroom Observation D. Survey

37 43 44 47

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL Instructor Interview Notes Appendix A First Meeting Notes 06 February 2013 Has one Chinese friend here, who came when she was 10 years old. Hes been here 11 years. He often feels conflicted between his Chinese and Brazil identities. With Chinese culture, invitations to dinner for example, is sometimes just about politeness, but a Brazilian boss was upset that she didnt go. Most friends are Brazilian. He almost feels more Brazilian. He did not know what to do at the beginning for dealing with students. In China, the teacher is well-respected. Students listen to the teacher. Two years of difficult students. Why didnt those students listen? The students know what they want. They know they dont want to study. In China, students dont need to consider what they want. He likes that here a student can consider what he or she needs. He does less writing with them because he respond better, because they dont seem to like the writing. Director was worried that new students might not be able to become adapted if the course has already progressed. The inclusion of culture might help them pick up. She also suggested he include business and etiquette, to see the usefulness of the subject. Students from last year who had some difficulty being engaged were more interested once he introduced business language and culture. Students were interested because they see themselves using Chinese. He wants to include business and culture. He teaches outside of this school. Those students want to learn for business. Most managers in this city think they can use English or hire a translator to communicate with Chinese businesses. Different between the schools. In Chinese school, they move directly into business. Here, he incorporates more applicable to school life. The people at the Chinese school already want to study. He can do a lot more with this group of 11th graders. He compares it to a marriage. People think culture is easy to adapt, but he sees it more like an iceberg. On the surface, it seems easy, but thats because youre ignoring everything below the surface.

37

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL Second Meeting Notes 27 February 2013 Teaching Chinese as a second language an online course 2006 The class focused on Chinese Culture Intercultural Communication Chinese Language Prepare Class Prepare Learners Pronunciation Planning College in Switzerland Hotel Management In Brazil Two years Ballet Dancer Started teaching Chinese and translator when arrived in Brazil

38

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL Third Meeting Notes 12 March 2013 For this meeting, we discussed survey results and potential ideas for intervention that I included in an email on March 11.

39

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL Fourth Meeting Notes 13 March 2013 The night before the instructor would meet his class, I sent an email to provide greater guidance and clarification than had been in the last email and our previous conversation.

40

The instructor seemed somewhat hesitant about my observation this day, so I requested that we meet afterward. Student Issue - FOB Following his class, we began by discussing a particular student FOB. During a presentation in the class, FOB kept her computer open, and was involved in something besides the class. Lee asked her to close her computer during the presentations, and she said, Uh huh. He says this repeated three or four times, until he went directly to her and told her she again she had to close her computer all the way. He says she then slammed the computer shut angrily. He took the computer and turned it into the office, which is a part of our policy for improper technology use. He spoke with FOB after class to address the situation. She told him that she does not care about the class, and if she doesnt care about the class, it shouldnt matter if she does something else. She told him that she does the same thing in other classes that she doesnt care about. He said he then told her that it is her duty to pay attention in class, and that it doesnt matter what she wants. I asked Lee if he thought this might be related to our goals for recognizing culture in the classroom and the culture we bring to the classroom. We also discussed how this goes beyond culture to examine the individual and how knowing the individual can help us reach our learning goals. Since our goal is to get her interested in the course so that she can learn, and we recognize that she has difficulty with authority and being told she has to do something, then telling her it is her duty to care about the class will not work. He added that she does well on tests and completes all her homework. This would make it appear that we are reaching our goals for her learning, and means she could serve as a perfect (although we have to recognize that she may not

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL change her opinion in two or three weeks) barometer for the effectiveness of our interventions. Unfortunately, BOF will now be suspended (this is her third technology misuse violation), and it is likely that her feelings about the course may grow even more resentful. Issue with Todays Lesson For this lesson, students were presenting information about the contextual meanings behind numbers in various regions of China (some numbers are incredibly important and symbolic, representing good and bad luck or death, etc.). The plan was for students to present in the groups they had been in while researching this information. The groups complained and said that they did not need to present because they were all going to present about the same topic numbers and their meaning. Lee tried to convince them that because they were presenting about different regions, the presentations would be different. They eventually presented. This issue magnifies the unwillingness of students to take an active, engaging role in the class, and the need to help them recognize the value of the course for themselves. This is why the flexibility of Lees curriculum can serve a great benefit for student engagement he can create the course around the goals they develop for themselves. While this still may not have a great impact on BOF, it certainly will have a greater impact than the alternative, where curriculum is decided for them without regard to their interest. Elements of Course Planned for Intervention Lee discussed culture today as an introduction to developing student-designed learning goals. They discussed stereotypes of Chinese culture, including censorship of the government an aspect prompted by a student. Other students then responded in ways that broke that stereotype down by providing anecdotes and context one said she has a friend in China with whom she interacts online, another said they know someone in China who uses Facebook, and another shared a story about Mark Zuckerberg visiting China. They then discussed perceptions of Brazil. Lee asked the Argentine student, AVM, if she had any false perceptions of Brazil before she arrived, and she shared how the idea is that Brazil is all jungle and little infrastructure. Goals Lee then asked students about learning goals, and students shared that they would like to learn about travel in China, colors, body parts, and sports. Part of my discussion with Lee was that the topics will help engage them to some extent, but the idea would be to have them develop goals for their learning, and I

41

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL provided him with the example: I want to learn the vocabulary that would help me interact with shopkeepers while traveling in Brazil. and I would like to understand customs for interacting with a family so that I am not accidentally offensive. This led Lee to develop ideas for the next lesson that would provide the context of storytelling (one of the interventions) with language lessons about travel he would like to have students role play as though they are traveling in China. We discussed how this would connect culture and the teaching of language, and considered providing necessary scripts or vocabulary lists of the words he will teach after the role playing (or before), and setting the role playing in multiple cities, so that students can recognize nuances of culture that exist between the many, diverse regions of China. At the end, Lee said he would send me a draft before the class next Wednesday, and I also asked that he reflect on the culture of his classroom and the culture of himself in a way that focuses on the incidents of todays class.

42

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL Administrator Interview Notes Appendix B First Meeting Notes 07 February 2013

43

The Chinese course was chosen to offer language options for students. Chinese is a growing need in international business. The inclusion of culture in the Chinese class was always intended, and is not the direct result of student or parent concern. The Chinese teacher and the director wanted to alter the course to include culture, because this echoes the ideas of intercultural awareness, which is part of the IB philosophy.

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL Classroom Observation Appendix C Objective-driven The second learning objective of number systems was addressed and achieved in a general sense, and this learning was then connected to application to everyday life and the use of the telephone. The first learning objective regarding Chinese characters functioned well, but I am curious about how well the students learned from the exercise, and if they were able to see connections between this portion of the class and the number systems portion of the class. If there were a larger, overarching lesson objective, what would it be? Would the review of characters and the learning of numbers both fit under that larger objective? Would students recognize those connections for their learning? Engagement Prior to this lesson, the instructor had been considering greater inclusion of cultural elements to increase student engagement. It was evident that there were moments in the lesson during which the instructor attempted to discuss culture for that purpose. The lesson began with a spontaneous lesson about a students name, and this mini-lesson, which seemed disconnected at first, was then brought back to the lesson about Chinese characters. The instructor also chose words to study that he thought would be engaging to this group of students (claw over the son means study). He would also ask questions during the lesson regarding cross cultural considerations of language (Why is it that they say meia meia and not seis seis?). The instructor may wish to regularly include such elements purposefully in his plans, so that he can also prepare for circumstances in which the attempt at engagement only works for a few students, and so that he can ensure that the engagement advances the lesson objectives.

44

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL Organization In many ways, organization of the lesson was well planned and well executed. The class followed a model for learning of introduction, reinforcement and interaction with learning, connection, and progression. The instructor used time well, continuing the lesson until the classs conclusion. In some circumstances, taking the lesson until the bell may deny the class an opportunity for concluding their learning, however, the instructor brought the learning to a close with a few minutes left of class, and then used the remaining moments for reinforcement. The class did seem to begin a little slowly, and students waited as the instructor checked attendance and collected homework. Following this first 7-10 minutes, instructions were given and groups were formed. Students could possibly be pushed to begin, with instructions on the board, while the instructor conducts beginning of the class responsibilities. While the instructor appeared in control of the movement of the lesson throughout, there were moments when students may not have been certain of the direction they were headed. There was a slight interruption by the Digital Media Productions class, and it wasnt clear if this was a planned interruption or not. It did seem to distract from the lesson, but the instructor recovered well. Guidance Although there were a couple moments where I was not clear if some aspects were connected to the overall lesson, the instructor did well to then explain that connection for the students.

45

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL The instructor interacted with students as they worked in groups. His interaction effectively used questioning to enhance the thinking of the students. He guided student thought, and rarely intervened to directly give answers. Were the groupings effective during the components of Chinese characters game? In Hahoons group, he worked at his own pace, providing information occasionally to Ingrid and Paulo, and this setup seemed to work for the three students. Pedro Henrique and Jos seemed to be conducting much of the work for their groups. At one point, the instructor worked very closely with one group, providing fantastic guidance to their learning. However, this lasted for about seven minutes, and the other two groups eventually stopped working during this time, moving to gossip and texting instead. Overall The lesson seemed incredibly successful, and it was clear that students moved through the lesson and advanced their learning. The greatest example of this was with the reading of phone numbers: Ivyan first said her phone number while reading from the textbook, but after further reinforcement, she then said her number several minutes later without looking at the book at all. An additional success was the instructors attempt to include culture for engagement. Students were engaged, and even excited, at various moments during the lesson.

46

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL Survey - Appendix D

47

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL

48

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL

49

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL

50

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL

51

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL

52

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL

53

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL

54

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL

55

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL

56

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL

57

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL

58

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL

59

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL

60

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL

61

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL

62

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL

63

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL

64

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL

65

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL

66

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL

67

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL

68

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL

69

CULTURE IN A CHINESE CLASS IN BRAZIL

70

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Ongoing Curriculum Alignment Process OverviewDokument9 SeitenOngoing Curriculum Alignment Process Overviewrodickwh7080Noch keine Bewertungen

- Teacher Induction ProgramDokument14 SeitenTeacher Induction Programrodickwh7080100% (1)

- Ongoing Curriculum Alignment Process OverviewDokument5 SeitenOngoing Curriculum Alignment Process Overviewrodickwh7080Noch keine Bewertungen

- Innovation StudyDokument27 SeitenInnovation Studyrodickwh7080Noch keine Bewertungen

- PYP Language Rubric DraftDokument3 SeitenPYP Language Rubric Draftrodickwh7080100% (4)

- Final Integrative Case StudyDokument36 SeitenFinal Integrative Case Studyrodickwh7080Noch keine Bewertungen

- Summative Videotape AnalysisDokument18 SeitenSummative Videotape Analysisrodickwh7080Noch keine Bewertungen

- Jeff Thompson Research ApplicationDokument33 SeitenJeff Thompson Research Applicationrodickwh7080Noch keine Bewertungen

- PD From The CC and Learning To Be LearnersDokument22 SeitenPD From The CC and Learning To Be Learnersrodickwh7080Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cultural Autobiography From OkunDokument2 SeitenCultural Autobiography From Okunrodickwh7080Noch keine Bewertungen

- Teacher Beliefs StatementDokument1 SeiteTeacher Beliefs Statementrodickwh7080Noch keine Bewertungen

- Work SamplingDokument36 SeitenWork Samplingrodickwh7080Noch keine Bewertungen

- Teaching and Learning EpisodeDokument17 SeitenTeaching and Learning Episoderodickwh7080Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Complete IB LearnerDokument13 SeitenThe Complete IB Learnerrodickwh7080Noch keine Bewertungen

- International PerspectivesDokument8 SeitenInternational Perspectivesrodickwh7080Noch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)