Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Carr Rusen Review Narration Historical

Hochgeladen von

sphmemCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Carr Rusen Review Narration Historical

Hochgeladen von

sphmemCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Wesleyan University

History as Orientation: Rsen on Historical Culture and Narration Geschichte im Kulturproze by Jrn Rsen; History: Narration, Interpretation, Orientation by Jrn Rsen Review by: David Carr History and Theory, Vol. 45, No. 2 (May, 2006), pp. 229-243 Published by: Wiley for Wesleyan University Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3874107 . Accessed: 26/03/2013 06:39

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Wiley and Wesleyan University are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to History and Theory.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 144.82.107.50 on Tue, 26 Mar 2013 06:39:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

History and Theory45 (May 2006), 229-243

? Wesleyan University 2006 ISSN: 0018-2656

REVIEWESSAYS

HISTORYAS ORIENTATION: ON HISTORICAL CULTUREAND NARRATION RUSEN GESCHICHTE By Jmn Riisen. Cologne: Bohlau Verlag, 2002. IMKULTURPROZEB. 298. Pp. x, HISTORY: ORIENTATION. INTERPRETATION, NARRATION, By Jim Rtisen. New York and Oxford: BerghahnBooks, 2005. Pp. x, 222 In the English-speakingworld since the mid-twentiethcentury,the philosophy of history has been conceived in close parallel to the philosophy of science: each was a critical reflection on knowledge, in the one case our knowledge of nature, in the other case our knowledge of the human past. But what is meant by "our" knowledge here? In the case of naturalscience it is clearly the knowledge possessed by the experts and expressed in the latest scientific theories. It is understood, of course, that such theories are never definitive, but they representthe paradigmor model of knowledge. Since most of us have a very limited understandingof such theories, and even less of the researchthat produces them, it is perhapsodd to call this "our"knowledge; but here the scientists are standingin for the rest of us. And so it is with history:"our"knowledge of the past is embodied in what the professionalhistorianstell us. We find them easier to understand, perhaps,than the physicists, and we recognize that their accounts, like those of naturalscience, are always subject to furtherreview. But what they say represents "our"knowledge of the past, even though "we"-the rest of us--do not ourselves participate in theirresearch.This conception of historicalknowledge is taken for grantedboth by those philosopherswho seek to show how such knowledge is possible and those skeptics who doubt or deny its possibility. This long-entrenchedepistemological approachto historicalknowledge, however, lends itself to a certain abstractness. Something is lost if philosophical reflection limits itself to the knowledge of the past we owe to the professional historians.The past figures in our lives in ways that far exceed the results of historicalresearch.We deal with and interpretthe past priorto and independentlyof our professionally warranted knowledge of it: it pervadesour sharedexperience and our sense of ourselves; it guides the ways we envisage the future and formulate social goals. It is embedded, in other words, in our culture. Even if our professional knowledge influences this broader,culturalsense of the past, it is also shaped by it. Terminologically,we can distinguish between the "historical studies" that are carriedout by our professional discipline and the broaderhistorical awareness that is embedded in our culture. A genuine understandingof historicalstudies will have to take accountof how they relateto and emerge from

This content downloaded from 144.82.107.50 on Tue, 26 Mar 2013 06:39:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

230

DAVID CARR

historicalawareness.One aspect of this is itself historical:that is, historicalstudies in our modem sense have emergedhistoricallyout of a broaderand older tradition. But there is more to it than this, since historical studies continue to exist side-by-side with, and in relationto, the historicalawarenessthat is partof present-day culture. A concrete understandingof historical knowledge, then, will place it in its culturaland historicalcontext. One of the distinguishingcharacteristicsof Jmrn Riisen's reflections on history is that they aim at concreteness in this sense. Historical knowledge must be understoodin its culturalcontext, and thatcontext is in turnhistorical.As he puts it, history "is more than only a matterof historicalstudies. It is an essential cultural factor in everybody's life" (H, 1).1 "Historyoccurs in a process of culture, which it also thematizes.It is, so to speak, a partof itself' (G, 1). Riisen has written extensively on the emergence of modem history, and of the accompanying reflections on history,in the classics of the nineteenth-century Germantradition,2 and this backgroundfurnisheshim with the context for approachinga numberof systematic questions about the natureand scope of historical knowledge. In the two collections of essays under review, one in English and one in German,systematic considerationsand historicalbackgroundare combined with remarkable coherence.WhatRilsen has to say offers a powerfulcorrectiveto the abstractness of both the analyticapproachto historicalknowledge and the postmodernassault on its validity. These collected essays cover a varietyof topics, andI shall not try to comment on all of them. What I hope to do instead is to articulatein a systematic way the theory that lies behind them. This theory is nowhere stated in explicit terms,but it emerges in the course of the author'streatment of differenttopics. I shall begin with some centralsystematic concepts, and then show how these concepts merge with a historical account of the beginnings of modern historical studies. In the second half of my essay I shall turnto Riisen's employmentof these systematic and historicalaccountsin dealing with recentchallenges to historicalknowledge, in particular those issuing from postmoderntheorists.

Riisen employs a number of key concepts. The first is what he calls historical culture-defined as the "totality of discourses in which a society understands itself and its futureby interpretingits past."These will include, but must not be limited to, professional historical studies. This culture must be analyzed in a fashion in order to measurethe place, status, and funcbroad, transdisciplinary tion of historical studies within it (G, 3).

1. "H" stands for History: Narration, Interpretation,Orientation, and "G" for Geschichte im Kulturprozef3. 2. To mention only a few of Riisen's important works: Konfigurationen des Historismus (Frankfurt:Suhrkamp, 1993); Historische Orientierung (Cologne: Bihlau 1994); Zeit und Sinn Fischer, 1990); Geschichte des Historismus(with FriedrichJaeger)(Munich:C. H. Beck, (Frankfurt: Orientation"is a completely revised 1992). The authornotes thatHistory: Narration,Interpretation, version of my 'Studies in Metahistory,'which was published in 1993 in the Series of the Human Sciences ResearchCouncil at Pretoria"(H, ix). A few essays appearin both volumes underreview, though sometimes the English versions differ in some detail from the German.

This content downloaded from 144.82.107.50 on Tue, 26 Mar 2013 06:39:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CULTUREAND NARRATION RUSEN ON HISTORICAL

231

The second is the concept of orientation-a powerful and suggestive notion that Riisen has used extensively in his writings as a clue to understandingthe place of history in our lives generally. Just as we orient ourselves in space, in orderto know where we are in our surroundings,so we orient ourselves in time, to know where we have come from and where we are going. Since we don't hold still but move aroundin space, sometimes we get lost and need to re-orientourselves. And so it is in time, accordingto Rtisen. Orientationis the term used to describe the function of historicalculturein the broadestsense, and professional history contributesto this in its own way. A key question concerns the peculiar natureof the role played by historical studies in orientation. A thirdkey concept is thatof narration.Riisen uses this concept very broadly. If historygenerallyis "timewhich has gained sense and meaning"(H, 2), it is by means of narration thatthis acquisitionoccurs. "Narratives createthe field where lives its cultural life in minds the the of history people, telling them who they are and what the temporalchange of themselves and their world is about"(H, 2). I shall begin with the thirdof these concepts, consideringRiisen's treatmentof the concept of narrative.Then we shall see how this concept relates to the other two, orientationand historical culture;and we shall also get an idea of how his systematic considerationsmerge with and complement his historical reflections. In the first three essays in History: Narration, Interpretation,Orientation, Riisen proposes a fourfoldtypology of narration: traditional,exemplary,critical, and genetic. He also calls these types of "narrative competence"or of "historical consciousness" (H, 26f.). Let us examine them in turn. Traditionalnarrativessimply express and articulate the continuity between presentsocial reality and the past from which it comes. Riisen mentions as examples "storieswhich tell aboutthe origin and genealogy of rulers,in orderto legitimate their domination;within religious communities,stories of theirfoundation; stories which are told at the occasion of centennials and otherjubilees" (H, 13). And he adds this revealing example: "in Boston you can even walk a traditional narrativefollowing the FreedomTrailpaintedas a red line on the sidewalk" (H, 13). Traditionalnarratives"define the 'togetherness'of social groups or whole societies in the termsof maintenanceof a sense of common origin"(H, 30). Such narratives define historical identity and self-understanding,and they have a decidedly moralimplicationas well: moralityis defined as tradition,thatis, what is valued is what contributes to the stability and continuity of the tradition. Change is importantonly to the extent that it reflects changeless values. Though Riisen states that certain historical works can be classified as traditionalnarratives, for the most parthere he is concernedwith forms of discourse and practice that lie outside professionalhistory. Exemplary narrativesgo beyond the moral values embodied in traditionby applyingthem throughexemplification.They "concretizeabstractrules and principles, telling stories which demonstratethe validity of the rules and principles in single cases" (H, 13). Here history is viewed "as a past recollected with a message or lesson for the present,as didactic:historia magistra vitae is a time-honored apothegm in the Westernhistoriographical tradition"(H, 30).

This content downloaded from 144.82.107.50 on Tue, 26 Mar 2013 06:39:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

232

DAVID CARR

Critical narrativesintroducenegativity into the picture: they raise questions about the validity of traditionalnarrativesand by implication about the values they reflect and the soundness of the lessons derived from them. Critical narratives are "based on people's ability to say no to traditions,rules and principles that have been handed down to them" (H, 14). In various ways, such critical thinkingunderminestraditionalmorality."Itscontributionto moralvalues lies in its critique of values" (H, 32). It injects elements of "critical argument"into moral reasoning. It points to culturalrelativity in values, and reveals "temporal conditioning factors," contrastingthese with the specious universality of supposedly timeless validity. It "confrontsclaims for validity with evidence based on temporalchange." In its most extreme form it presents itself as a critiqueof morality in general, as found in Marx's critique of bourgeois values or Nietzsche's genealogy of morals (H, 32). Genetic narrativesemerge as the integrationof the critical with the traditional and the exemplary.If the critical stage pitted temporalchange against the supposedly timeless and constantvalues of the tradition,the genetic stage recognizes that value inheres in temporal change itself, and it usually expresses this by appealingto the form of progress.Changeis not only accepted,it becomes essential. Personaland social identities are both markedby a process of self-definition (the Germanidea of Bildung). "Temporalchange sheds its threateningaspect, instead becoming the path on which options are opened up for humanactivity to create a new world"(H, 33). By presentingthese four modes of narrationor "narrative competence"as a typology, Riisen obviously believes that they representa systematic breakdown based on conceptual differences. The implicationis that these types could exist at any time and that the connections among them would be preserved. And indeed, we can easily think of all four as co-existing in the present day. Traditionalnarrativesare still part of popularculture and political rhetoric;we still look to the heroes of the past for moral lessons; and as long as these practices exist, critics will come along to debunkthem. The more sober assessments of our historianswill reflect the attemptto integratethe three previous modes. In any given historical text, as Riisen suggests, there may be elements of all four types (H, 15), and the typology allows us to identify and separatethem, in order betterto understand the text. Riisen believes, however, thathis typology is more thanmerely static and conceptual.Thereis a logical progression,he says, "fromthe traditionalto the exemCriticalnarrativeserves plary,and from the exemplaryto the genetical narrative. This enables him to proas the necessarycatalyst in this transformation" (H, 15). pose no less than a theory of the "ontogeneticdevelopment of historical consciousness" (H, 34). The traditionalform can exist on its own and is not dependent on the others.The exemplarytype is an offshoot of the traditional,as we have seen, and thus depends on it as a presupposition.Criticalnarrativeis dependent on the presence of already existing traditionaland exemplary forms, for it is against these that its critique is directed. And the genetic form, as Riisen conceives it, is a synthesis of the critical, the traditional,and the exemplary.

This content downloaded from 144.82.107.50 on Tue, 26 Mar 2013 06:39:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

RUSEN ON HISTORICALCULTUREAND NARRATION

233

This ontogenetic theory gives a temporalsense to the logical order,and thus provides the basis, as might be expected, for an account of the history of historical consciousness and of historiography,a periodizationof historical thinking. Above all, the pivotal or catalytic critical type of narrationoffers the key to the transitionfrompremodernto modem historicalthinkingat the understanding turnof the nineteenthcenturyin Europe.Koselleck has writtenabout this period as the abandonmentof the historia magistra vitae model of historical writing, showing how it was connected with a new conception of historical time, especially the future.In the Enlightenmentthe historical future comes under human control and prediction, and is no longer a mattermerely of prophecy, hope, or aspiration.3 Rtisen's emphasis is on the methodsdeveloped by modernhistorians for dealing with the past. It is the concept of method that ushers in historical thinkingin the modernsense. Geschichteim Kulturprozef3 begins with threeessays that thematizethe beginnings of modern history in nineteenth-centuryEurope. The introduction of methodicalconsiderationsinto the writing of history is what lends it its statusas Wissenschaft.But this in turn leads to a conception of historical reality that can be contrastedwith the "religious meaning"of the historical process. Here religion, and in particularthe Christianreligion, occupies the place of the "tradiin Riisen's fourfold classification.The Christianstory,from cretional narrative" ation and the fall throughincarnationand redemption,provides Europeansociety with a profoundaccount of the continuitybetween present and past, gives it a sense of identity through time and in contrast to outsiders, and lends itself to moral exemplarsin the figure of Christ and the lives of saints and martyrs.It is against this powerful, unifying story that the skeptical doubts of the Enlightenment thinkers are raised, and it is no accident that the concept of historical method finds some of its earliest manifestations in biblical text-critique and hermeneutics,the search for the historical Jesus, and the historical examination of the early church.Our knowledge of the importantevents of the past is recognized as deriving from sources that can be compared and subjected to critical analysis. The past becomes an object of research, something whose surface meaning is not taken for granted,something whose truthmust be uncovered by a cognitive procedure. In the process, however, the past itself, and with it the sacred writings, are robbed of their properly religious sense. They suffer from what Weber later called disenchantment,losing their traditionalrole in forming the identity and moral cohesion of society. Thus the development of historical knowledge plays a crucial role in the dawn of modernity,with all its great accomplishmentsand all its problems.But history also offers itself, in various ways, as the solution to the very problemit has created.In the place of religious faith it proposes faith in the progress of mankind. as manifestedin the nineteenthcenThis is what Riisen calls genetic narrative, tury.While it is alreadypresentin the thinkersof the late Enlightenment,such as

3. Reinhard Koselleck, Futures Past: On the Semantics of Historical Time, transl. K. Tribe (Cambridge,Mass.: MIT Press, 1985), 21ff.

This content downloaded from 144.82.107.50 on Tue, 26 Mar 2013 06:39:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

234

DAVID CARR

Kant, its most elaborateform is Hegel's philosophy of history, which explicitly attemptsto fuse rationalprogress with the religious tradition.Hegel's work can be seen as a rear-guard effort, even an act of desperation,tryingto reunite what the Enlightenmenthad taken apart.The salvation story is now embodied in history itself, complete with political redemptionand a new theodicy. "Religious transcendence, which in Christianity had already temporalized and finitized itself, becomes the inner spiritualcoherence of the temporalchanges in man and his world"(G, 33). Trimmedof its religious trappingsand outfittedwith the aura of social science, the belief in historical salvation survives in Comptean positivism and in Marx's historicalmaterialism. The major representativesof the new historical profession, notably Leopold von Ranke, are less thanenthusiasticaboutthese philosophies of history.The latter appearto betraythe sober and critical restraintthat is the essence of the new history. Idealistic constructionslike Hegel's are "extra-scientific,metaphysical speculations" and are seen as "incompatiblewith the progress of knowledge throughresearch,indeed as threateningsuch research"(G, 33). At the same time the historianscannot give up the conviction that history "makes sense" at some level; indeed this conviction seems to animateand motivate theirwork. But what sort of sense-making is this? It is this question that leads Riisen into the thorny terrainabout which he has alreadywrittenextensively, that of the metahistorical reflections of the so-called "historicalschool" that go underthe general name of Historismus. This term is notoriouslybroad,and Riisen has done more than anyone to chart its ambiguouscourse throughoutthe nineteenthand twentiethcenturies.Central figures such as Ranke and Droysen obviously yearn, as does Hegel, for a connection between theirhistoricalresearchesandtheirreligious beliefs. Rankeconsidered research as a kind of rational religious observance (Gottesdienst)-the same thing Hegel had said about speculative thinking. Droysen went even further, as quoted by Riisen: "Ourbelief gives us the consolation that we are borne by God's hand, that it guides our destinies, large and small. And the science of history has no higher task thanthat of justifying this belief; for [Wissenschaft] that reason it is science" (G, 35). But in the end the drive for historical knowledge outranthese yearningsand acquireda life of its own. As such, such knowledge was neither dependent on religious belief nor did it serve the purpose of supportingreligious belief. Indeed, it gave rise to a currentof thoughtthat both put itself in place of religious belief and ultimately underminedit. Though the term Historismus has been used in many ways, Riisen believes that it can be employed meaningfully to characterizethis currentor form of thought that lay behind the practice of the new historical discipline of the nineteenth century, especially in Germany.As he said in his Geschichte des Historismus,there is a distinctive "manner of confrontingthe humanpast which is typical of the historical sciences since the turn of the nineteenth century"and which constitutes a It is both a view of human "specifically modern form of historical thinking."4 natureand a scientific paradigm.

4. Riisen,Geschichte 7. des Historismus,

This content downloaded from 144.82.107.50 on Tue, 26 Mar 2013 06:39:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CULTUREAND NARRATION RUSEN ON HISTORICAL

235

Before we look in more detail at Historismusand the problemsit raises, let us sum up what we have covered so far. Rtisen's fourfold classification or typology as a "logof narrative(traditional, exemplary,critical, and genetic), reinterpreted ical progression,"has providedthe basis for a historical accountof the transition from premodernto modem historicalwriting and thinking.We should perhapsbe cautious about finding a "logical" progressionwithin a historical development, even the developmentof historicalthoughtitself, since this suggests a temptation that led to some of the more notorious schemes of the classical philosophers of history.This may be anotherversion of the fallacy that what did happen had to happen.But Riisen makes a convincing case. He has given us an account that is both systematic and historicalof the emergence and the success of the historical profession in the nineteenthcentury. We can now see a connection between this account of historicalnarrationand the othertwo key concepts we mentionedat the outset:historical cultureand orientation. If the formeris a society's awarenessof the past in the broadestsense, the emergence of historicalscience in the nineteenthcenturyrepresentsEurope's way of articulatingits historical culturein a systematic and focused way. And if historical culture is society's way of orienting itself in time, the emergence of modem history respondsto the need for reorientationarising out of the immense changes wroughtby the revolutions and wars of the turn of the nineteenthcentury.As Riisen puts it, the differencebetween past and futurelooms so large that "humanlife-praxis can only be culturally oriented by conceptions of time that and change as such. Temporalchange is no longer subthematizetransformation dued by historical meaning (either by powerful belief in traditionsor in empirically confirmedrules of conduct);instead, change itself produces meaning" (G, 55). The result is a triumphfor historicalknowledge and research,and the establishment of a professionaldiscipline that persists to the presentday.

The problem with Historismus,understoodin this sense, is that it contains tensions and contradictionsthat threatenits coherence from the outset. There is a deep connection, as we shall see, between these problemsof Historismus,which begin to make themselves felt at the end of the nineteenthcentury,and the conhistoricalknowledge in our own day, many of them assotroversiessurrounding ciated with the term "postmodem." These controversies form the heart of Riisen's systematic investigations, for which his historical account of the emergence of Historismushas preparedthe way. Considerthe following elements of classical Historismus.First,it is convinced of the thoroughlyhistoricalcharacterof humannatureand of all humanendeavors. History thus comes to replace reason or religion as the key to understanding humanity.Riisen quotes ErnstTroeltsch's well-known, retrospectivecharacterization of Historismus as the "thoroughgoinghistoricizationof all our thinking aboutman, his cultureand his values" (G, 47f.). Second, "historicalscience" has now emerged as the mode of access to humanityso understood.This new science

This content downloaded from 144.82.107.50 on Tue, 26 Mar 2013 06:39:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

236

DAVID CARR

stands in the same relation to its predecessorsas the new physics to alchemy or the new medicine to the folk remedies of the past. It has its own methods for assuring its objectivity and securing its results as knowledge ratherthan mere opinion. Riisen characterizesthis move, in Husserlianfashion, as the separation of science from the lifeworld (G, 46). At the same time, fully aware of the difference between humanand naturalsciences, historiansbase theirknowledge not on observationand experimentbut on understanding and interpretation. Finally, the new science of history believes it finds evidence of developmentin the largescale course of historical events, which comes close to the reaffirmationof the notion of progress. The crucial systematic question is whether these aspects of Historismuscan peacefully coexist. In keeping with the thesis of historicization,each historical epoch will be thoroughly self-contained and must be understoodstrictly in its own terms.The past is utterlydifferentfrom the present.How then can the past, in its radicalotherness,be understoodby the science of the present?How can we understand those whose life is governedby historicallydifferentculturesand values? How can we comparedifferentepochs historicallyin orderto discern a progression of any kind? And what if the science of history, on which we base all our claims and of which we are so proud,itself turnsout to be just an expression of our cultureand values, a productof our historicalepoch, reducingeverything we say about the past to something merely constructedin the present? In this mannerthe new objective science of history seems implicitly to undermineits own objectivity. It is no wonder that EdmundHusserl, writing in 1910, spoke of Historizismus in the same breathwith Weltanschauungsphilosophie ("world-viewphilosophy") as one of the great threatsto the perennialideal of "Philosophyas rigorous science."5 It is probably significant that Husserl uses Historizismus rather than Historismus, and thinks of it, in parallel to his terms Psychologismus and not as the mere practiceof the discipline in question,but as a Anthropologismus, doctrine based on it.6 His target above all is Dilthey, whom he philosophical and hence with identifies, rightly or wrongly, with Weltanschauungsphilosophie historical relativism. But there is no doubt that Historismus, as described by Riisen, is implicatedin Husserl's attack.It is, indeed, more thanjust the practice of history; when Riisen describes it as "a specifically modernform of historical thinking" he has in mind something as broad as a Weltanschauung.While Husserl clearly distinguishes between history as such and Historizismus, he believes that views like the "thoroughgoinghistoricizationof all our thinking," which accompanythe great flourishingof historicalknowledge in the nineteenth century,lead to the paradoxthathistoricalknowledge itself, andthe values of science and objectivity,become thoroughlyhistoricizedalong with everythingelse. Thus the idea that history,or science in general, or indeed philosophy,could rise above its own circumstancesand gain access to a realm of objective truth,seems to be underminedin advance.

5. Edmund Husserl, Philosophie als strenge Wissenschaft (Frankfurt:Vittorio Klostermann,

1965),49ff. 6. See Riisen's discussion of theterms Historismus andHistorizismus atthebeginning interesting of his Geschichte 4f. desHistorismus,

This content downloaded from 144.82.107.50 on Tue, 26 Mar 2013 06:39:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ROSEN ON HISTORICAL CULTUREAND NARRATION

237

Husserl's critiqueof Historizismuscan be seen as an early manifestationof a long series of controversiesabouthistoricalknowledgethatcontinuedthroughthe twentiethcentury.The postmoderncritiqueof more recentyears is only the latest version. On the one hand the historicalprofession has spreadfar and wide from its origins in nineteenth-century Germanyand has continuedto go aboutits business with a certaindegree of self-confidence, or at least institutionalstability.It which is itself anothhas its home, after all, in the modern"researchuniversity," er of the importantculturalexports of nineteenth-century Germany.On the other hand, the status of historicalknowledge has been questionedfrom all sides, and this has engaged historiansthemselves no less than culture-criticsand philosophers. It has also had its influence on developmentsin the practiceof history. The reproachof "idealism"and "subjectivism"was a perennialproblem for historians who based their claims on Verstehen.The attempt to make history more objective appearedvery early on, in the attemptof the early positivists to base historical knowledge on "social science," conceived as a kind of "physics of society." Marxisthistory shares this same motivation and scientistic commitment; the Annales school, and relatedmoves toward social and economic history, can be seen in the same light. But apartfrom certainpracticinghistorians,few have been convinced, at least at the theoreticallevel, by these attemptsto think of historyas a rigorouslyobjective science. There was a brief attemptby the neopositivistic philosophersof the analytic school, startingwith Carl G. Hempel in the 1940s, to get rid of Verstehen by conceiving of historical explanationon the model of causal-scientific explanation.Like the reductionist"unity-of-science" movement of which it was a part, this attempt soon succumbed to severe criticism, in partbecause its logical approachseemed to have little to do with historians'actualpractice.And since thatpracticecontinuedto be based at least in part the claim of historyto be a Wissenschaft,which was at the heartof on Verstehen, the new history,has remainedsuspect. Another aspect of historicist thinking, the at least implicit belief in human progress, has also not fared well. Here historical developments, ratherthan theoretical problems, played the greatest role. It was in Germany, where Historismushad begun and flourished,that the concept of progress came in for its most intense and critical scrutiny,especially after WorldWar I. Talk of the "crisisof Historismus"(Troeltsch,Meineke, Heussi) derivedat least in partfrom the fact that Germanyitself was sufferinga nationalcrisis and confusion brought on by the defeats, economic upheavals, and perceived national humiliations caused by the war. After WorldWar II, of course, it was the revelations of the Holocaust, together with the experience of the war itself, that made belief in progressalmost universallyunacceptable,and not just in Germany.Here it could be arguedthat while the developmentof the historical profession, and the practice of research and writing, had been wedded to the idea of progress, they did not dependon this idea for theirown validity and could carryon withoutit. What is undermined,however, as Riisen is keenly aware, is the capacity of historical knowledge to provide orientationand a sense of identity to those who have lost both to the greatupheavalsof the mid-twentiethcentury.If history could perform

This content downloaded from 144.82.107.50 on Tue, 26 Mar 2013 06:39:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

238

DAVID CARR

this service at the beginning of the nineteenthcentury,making historical sense of the great changes that were underway,it seemed powerless to succeed in the postwarworld. As Riisen puts it, "historyis a narrativeraft floating on the natural streamof time" which serves to orient humanaction and suffering"in practical life and in the inner life of the human self. Vessels of this sort, as they have been constructedand used in our historical culture(and in the modernperiod it was more like a steamship than a raft), are no longer seaworthy"(G, 76). It is impossible to conceive of a relation of before and after whose idea of temporal flow "would give the Holocaust a convincing historicalmeaning"(G, 76). Against the background of these successive blows to the confidence of Historismusin the early and the middle twentiethcentury,the attacksof the late twentiethcentury,underthe broadheading of the postmoderncritique,appearas a coup de grace. It is these attacks that occupy the major part of Rtisen's systematic writing in these volumes. While it is not quite correct that he offers a defense of history against the postmoderncritique,he certainly offers an elaborate and insightful response to it, one that takes seriously,but not uncritically,its many-sidedcomplexity. in advance often cite its irritatThose who wish to dismiss "postmodernism" ing ambiguityand breadth.A concept that seems to mean everythingmay in the end mean nothing. Nevertheless it deserves to be examined, as a historian of ideas like Riisen must recognize. It is in some respects like Historismusitself: it is a broad and powerful currentof thought that has had wide-ranginginfluence even though it contains contradictionsand cannot be reduced to a series of neat propositions. Perhaps the point of departureand most enduring accomplishmentof postmodernism is its attempt to thematize modernityor the modern in a way that takes a distance from this phenomenonand calls into question its majorfeatures rather than endorsing or subscribing to them. Modernity has existed as an unquestioned set of values and attitudes in Western culture at least since the Enlightenmentand up to the presentday, and the only way to question it was to be premodern,primitive, reactionary, hopelessly behind the times. It is by staking out a position outside and beyond the modem thatthe postmodernistsacquire their name, even though the details of their own position (that is, the standpoint from which they launch their critique)remainto be worked out. Historismusoffers itself as a prime targetof the postmoderncritique.With its double commitment to the Enlightenmentidea of progress and to the role of Wissenschaftas the agent of progress, it can be seen as the high point and cultakes over minationof modernity.It is humanisticin essence, since "humanity" the role of God and serves as the instrumentof its own salvation.Humanbeings do this not as individuals but on the broad stage of history. Born and raised in Europeat the time of Europe'sexuberantexpansionand colonialism, the idea of Historismusis implicitly committedto the superiorposition of Europein relation to the rest of the world. Thus it reveals itself as a congeries of beliefs and attitudes that have become seriously suspect in the course of the twentiethcentury.

This content downloaded from 144.82.107.50 on Tue, 26 Mar 2013 06:39:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ROSEN ON HISTORICAL CULTUREAND NARRATION

239

While these suspicionshad alreadybeen raisedin generalterms, as we have seen, they are given a decisive new twist by the postmoderncritique. What the latteradds to this general picturederives from what has been called the "linguistic turn"in philosophy and in culture studies generally. It began as parallel but unrelateddevelopmentsin analytic and continentalphilosophy: late Wittgenstein,Austin, and Searle on the one side, Heidegger and Gadameron the other. Language is the medium of knowledge, of our access to reality, to being itself. If you want to understand these things, look to the language in which they are expressed. In spite of this common insight at the origin, the two sides went distinctly separateways: for late analytic philosophy, language was seen more and more as an instrumentfor humanpractice;for continentalphilosophy,esperevolution, human practice seemed more and more cially after the structuralist the passive instrumentof language, now conceived as an autonomousrealm of its own. History enters the picturein explicit terms when philosophersand other theorists draw attentionto its narrative character. Analytic philosophers like Arthur Danto and Louis Mink initiated this process in the 1960s. Still pursuingthe old question of whetherhistory can qualify as a science, and of how it comparesto the naturalsciences, they discover that history essentially tells stories about the past, and thatthe constructionof stories follows rules thatare very differentfrom the rules for constructing scientific theories. This means that the best way to understand history is not to compareit to empiricalscience but to view it as a literary genre. For the thinkers of the modern historicist tradition and for many practicing,professionalhistorians,this was like uncovering an old family scandal that has for years been successfully hushed up. Since the rise of the new history in the nineteenthcentury,its narrativeaspect had been ignored altogetheror relegated to the secondaryrole of how one "writesup" the results of a scientific underserious investigationby literarytheorists, investigation.But now narrative, was found to embody complex structuresand to representa sophisticatedconceptual frameworkfor dealing with experience. HaydenWhite's tour de force of 1973, Metahistory,was a pivotal work that applied the ideas of literarytheorists such as Roland Barthes and NorthropFrye to some of the classical nineteenthcenturyhistorianssuch as Ranke and Michelet. They were portrayedas unknowingly following tacit rules for storytelling,which lie embedded in our culture. The problemwith terms like "narrative" and "storytelling" is thatthey suggest an activity thatis more at home in the realm of fiction than fact, an activity guided by aesthetic rather than scientific criteria. History begins to look like an inquirywedded to means thatare ill-suited to and maybe even incompatiblewith its supposed aim, which is to tell the truth about the past. Historical "Wissena dubious figure which synthesizes scienschaft" appearsas "a hermaphrodite, tific rationalityand literarytextuality"(G, 127). Hayden White and otherswaste no time giving examples of historiography that is more concerned with telling a good story than telling the truth. Under the influence of Barthes and later Foucault,White portrayshistory as pretendingto be value-neutralwhile in real-

This content downloaded from 144.82.107.50 on Tue, 26 Mar 2013 06:39:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

240

DAVID CARR

ity pushing its Eurocentricmoral and political view of the world in the interests of power and manipulation. In view of the account that Riisen has given us about the fortunesand fate of the study of history,these developmentsappearas a sad denouement.Presenting itself in the nineteenth century as the triumph of scientific knowledge over a dubiousand disreputable past as a mere literarygenre, the study of history seems now, in the end, to have reverted to its original self, its scientific pretensions deflated and unmasked. Or so the postmoderncritique would have us believe. History has nothing left but its essentially premodernrole, that is, what Rilsen, It is just one of socinarrative." in his original classification, called "traditional ety's ways of rememberingits past, preservingcontinuity with the present, and establishingand assertingits identity.The line between popularcommemoration and historical "science"disappears. Rilsen recounts these developments as the expert historianof ideas that he is, issue for debate. but he wants to treatthe postmoderncritiqueas a contemporary His response is very balanced, as one might expect. He subscribes to some of historicalknowledge. For one thing, aspects of the postmoderninterpretation as we have seen, his theory has taken narrative as its central focus. Historical thinking,or even more broadly,historical culture, accomplishes its work of orientationby producingnarratives,and it is these that Rusen has classified in the to "genetical."This emphasis on fourfold scheme that runs from "traditional" narrativeis by no means uncontroversial,and many voices have been raised againstit. As we have seen, attemptsto renderhistory more scientific, from positivism to the Annales school and beyond-including Foucault-have argued that history can divest itself of its narrative,"literary" aspect and ascend to genuine knowledge of the past. It is possible to view notjust recent social historybut some of the great classics of older history-Carcopino, Huizinga, even histories. "Real"history,"serious"history,on this Burckhardt-as non-narrative view, is not narrativeat all. Hayden White and Paul Ricoeur have both argued,though in differentways, that such apparentlynon-narrative history still has an implicit and hidden narraand Riisen apparentlyshares their view, though he doesn't argue tive structure,7 for it here. In any case, as the example of Ricoeur shows, one can be a "narrativist" in the broad sense without sharingthe postmodernslant. The latter view but that,because of this, history must relinis notjust that all historyis narrative, quish all claims to objectivity and any pretenseto telling the truthaboutthe past. This is the view that Riisen opposes vigorously. A key concept in the postmoderncritique is that of fiction. In historical writing, accordingto the postmodernview, any claim that goes beyond the assertion of bare facts, any attempt to relate them to one another,interprettheir significance, or trace them to underlying patterns is supposedly a product of the author'simaginationand thus has the status of fiction. It is therebyto be understood as "creative,""poetic,"and essentially aesthetic in character,placing his7. HaydenWhite, "TheStructureof HistoricalNarrative,"Clio 1 (1972), 5-19; Paul Ricoeur,Time and Narrative, transl. Kathleen McLaughlin and David Pellauer (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984), I, 206ff.

This content downloaded from 144.82.107.50 on Tue, 26 Mar 2013 06:39:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ANDNARRATION ONHISTORICAL CULTURE ROSEN

241

tory beyond reason and into the category of imaginative literature.Riisen correctly points out the dubious assumptionson which this theory rests. It is possible "only underthe unquestionedpresuppositionof a positivistic epistemology" (G, 115). Scientists and historiansof the nineteenthcentury may have fervently desired cognitive access to somefactum brutum,unmediatedby any interpretive frameworkor intention. But the idea had alreadybeen challenged by Kant and has long been regardedas questionableat best. Moreover,only on this assumption does the alleged contrastbetween "fact"and "fiction"make sense. Not all is arbitrary; are more appropriate than others, some interpretations interpretation more capable than others of dealing with a wide range of phenomena.The task of "making sense" of the events of the past may indeed require the use of the imagination.But not everythingenvisaged by the imaginationis imaginaryin the sense of fictional. Fiction is the deliberateinvention of imaginarypersons, actions, and events, primarilyby telling stories about them. But not all stories are fictional in this sense. History is only one form in which we try to tell true stories. Memoirs, biographies and autobiographies,anecdotes, medical case histories, and court testimonies are other such forms. Narrativeand objectivity are not in principle opposed, as the postmoderncritiqueimplies, and Riisen arguesthat the two conbut are constrainedby our cepts can coexist. The stories we tell are not arbitrary our of human nature our sense andpsychology, by our sources, by experience,by notions of what is possible. Most important,narrativesare submittedfor review to the others who make up our community and who share these notions with us. The others serve as check and constrainton our claims, assuring that they will not be accepted if they are arbitrary or "subjective."In the context of history,the for the consistence and shares scholarlycommunity commonly accepted"criteria coherence of historicalnarration" as (G, 118). Objectivitycan thus be interpreted intersubjectivityand as such can be seen as a featureof narrative.None of these constraintsor checks can ever assure or guaranteethe objectivity of any given narrative.But their importanceand their role in historicalknowledge undermine the claim thatnarrativesare "merelyaesthetic"and thus subjectiveand arbitrary. and objectivityprovide Riisen with the occasion These reflections on narrative for some furtherremarkson the topic of orientation, which, as we've seen, is a central concept in his whole approach.The idea of history as orienting the individual and the communityin time might seem best suited to the premodern,and perhaps the postmodern,conceptions of history, but not to the modem idea of historical knowledge. Orientationis after all a practical notion, well suited to those "traditional" and "exemplary" narrativesthat reinforcecommunalidentity and values, and then apply those values to everyday life. The postmodernconception, too, with its emphasison the aesthetic, memorial,and political function of history,fits well with the idea of orientation.Modern, "scientific,"history,by contrast, seems to renounce the orienting role as its premier article of faith. Riisen introducesRanke'smuch quoted words, which are often treatedas the epigraph and motto for the modernistview of history: "Historyhas been accorded the role of judging the past in orderto provide the contemporary world with use-

This content downloaded from 144.82.107.50 on Tue, 26 Mar 2013 06:39:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

242

DAVID CARR

ful instructionfor futureyears. The presentstudy renounces such high offices: it wants only to show how it really was [zeigen, wie es eigentlich gewesen]" (G, 100). Ranke's false modesty communicates his ill-disguised contempt for any history that seeks a practical,orientingrole. Yet this opposition between objectivity and orientationis ill-conceived. If we consider the idea of spatial orientationfrom which this metaphoris derived, we can easily see that the two go hand in hand. Seeking our bearings in the spatial environment,we need to know our surroundingsas they really are, not as we wish they were. Imaginarylandscapes are of no use whateverin getting us from here to there. To aid in spatial orientation,we use maps because they give us a bird's-eye perspective, allowing us to overcome the limits of our earthbound view. As Riisen shows, Ranke and his fellow historianshad a strong sense that their new scientific discipline could play an analogous role, allowing us to surmount our limited perspective and gain access to the reality of history. Understood in this way, it could serve the culturalorientationof practical life, especially in politics. Thus even for Ranke, "politics, as action directed toward the future,appearsas the other side of historicalknowledge directedtowardthe past" (G, 107). Ranke objected not to action based on genuine historical knowledge, but to history that has the limited goal of having practicalresults. Such history will inevitably be of limited scale, too small in its vision to achieve the bird'seye perspectivehe sought. As we might expect, Riisen does not simply endorseRanke'soptimisticclaims of for the practical value of historical knowledge. But a deeper understanding those claims contributesto his broad response to the postmodernchallenge. He wants to keep narrativeat the center of his reflections on history without accepting the implications put forwardby the postmoderncritics. Consideringhistory as a species of the genus "storytelling"permits him to see professional or academic history,historicalknowledge proper,as part of the largerphenomenonhe calls historicalculture,thatis, stories aboutthe past runningfrom popularlegend to political rhetoric.But he arguesagainstthe implication and folk representation that the narrativeunderstandingof history places it in an exclusively aesthetic domain and deprives it of any capacity for objectivity. Considered as an intersubjective enterprisewith agreed-uponrules and methods, and as a self-critical pretensions,historycan validly claim to tell us the truth process without arrogant about the past and serve society's need for orientation. There is a furtheraspect of the postmoderncritique to which Riisen is espeAs we've seen, his syscially sensitive, and this is the reproachof Eurocentrism. tematicreflections on history are always intertwinedwith a deeply informedhistorical account of the emergence of the modem discipline in nineteenth-century Germany.But as we noted at the beginning of this essay, Rtisen's attentionto modernhistoricalknowledge never loses sight of its relationto the broaderbackground of historical culture. Under the rubric of historical culture, he devotes some of his essays to intercultural differences,problems of nationalidentity and xenophobia,and possibilities for communicationbetween cultures.He is particularly interestedin how to understandthe historical cultureof other societies in

This content downloaded from 144.82.107.50 on Tue, 26 Mar 2013 06:39:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CULTUREAND NARRATION ROSEN ON HISTORICAL

243

a way that is not itself ethnocentric,that is, in such a way that does not impose the investigator's idea of history on what is investigated. Among the notions Westernscholarsare likely to take for grantedin examining otherculturesare the sharpdistinction between history and the work of poetic imagination;the focus on written,as opposed to oral, culture;and the link between history and the state (G, 235f.). Like the postmoderncritics, he sees these as Eurocentricprejudices that impose our own concepts on the rest of the world and lead us to overlook many of the ways thathistoricalawarenessis embodied in non-Westerncultures. He offers his own typology of historicalnarration-traditional, exemplary,critical, and genetic-as one that can succeed in the realm of intercultural comparison (G, 255). This may be regardedas questionable,given the degree to which this typology is tailored,as we've seen, to the origins of modernhistory in the West. In general Riisen's attempt to rise above prejudice, especially in the long essay is "TheoreticalApproachesto an Intercultural Comparisonof Historiography," ratherabstractand sharesin the usual difficulties of trying to establish a presuppositionless standpoint.Ratherthan trying to defend one's position in advance against all criticisms, it is betterto plunge ahead, armedwith a sympatheticand self-critical attitude,and do one's best in being open to the other and the strange. This is an attitudethatJrnm Riisen has in abundance,and it is very much in evidence, along with his deep historical knowledge and his systematic clarity, in these collected essays. They touch on many more topics than I have been able to cover in this account. For example, other essays deal with human rights, modernization,and "HolocaustMemory and GermanIdentity."Here I have tried to focus on the theoretical and historical unity that underlies these essays, as expressed in some of Riisen's basic concepts and his account of their embodiment in the history and developmentof ideas.

DAVIDCARR

Emory University

This content downloaded from 144.82.107.50 on Tue, 26 Mar 2013 06:39:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- 101 ReactDokument221 Seiten101 ReactrupeshNoch keine Bewertungen

- CRM Report with Order, Activity and Survey DataDokument5 SeitenCRM Report with Order, Activity and Survey DataAgus SantosoNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Impact of Empire) Olivier Hekster, Sebastian Schmidt-Hofner, Christian Witschel, Olivier Hekster, Sebastian Schmidt-Hofner, Christian Witschel-Ritual Dynamics and Religious Change in The Roman EmpireDokument393 Seiten(Impact of Empire) Olivier Hekster, Sebastian Schmidt-Hofner, Christian Witschel, Olivier Hekster, Sebastian Schmidt-Hofner, Christian Witschel-Ritual Dynamics and Religious Change in The Roman Empiresphmem100% (2)

- 3 Stroumsa, The End of SacrificeDokument15 Seiten3 Stroumsa, The End of SacrificesphmemNoch keine Bewertungen

- BAKKER, S. J (2009), The Noun Phrase in Ancient GreekDokument336 SeitenBAKKER, S. J (2009), The Noun Phrase in Ancient GreekIstván Drimál100% (1)

- Basic Punctuation Marks PowerpointDokument12 SeitenBasic Punctuation Marks PowerpointBelle Madreo100% (1)

- The Routledge Handbook of Spanish Phonology 1nbsped 0415785693 9780415785693 - CompressDokument553 SeitenThe Routledge Handbook of Spanish Phonology 1nbsped 0415785693 9780415785693 - CompressDuniaZad Ea EaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Popular History of Russia, Earliest Times To 1880, VOL 3 of 3 - Alfred RambaudDokument299 SeitenA Popular History of Russia, Earliest Times To 1880, VOL 3 of 3 - Alfred RambaudWaterwind100% (2)

- Afro-Asian Literature: Hymns That Formed The Cornerstone of Aryan CultureDokument5 SeitenAfro-Asian Literature: Hymns That Formed The Cornerstone of Aryan CultureMiyuki Nakata100% (1)

- Beard Review BrownDokument4 SeitenBeard Review BrownsphmemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Russia Religion Ritual PowerDokument27 SeitenRussia Religion Ritual PowersphmemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Beard Review BrownDokument4 SeitenBeard Review BrownsphmemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Burke Variations On ProvidenceDokument30 SeitenBurke Variations On ProvidencesphmemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Davidson - Ethics As AsceticsDokument14 SeitenDavidson - Ethics As AsceticssphmemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Praxis PaperDokument2 SeitenPraxis Paperapi-447083032Noch keine Bewertungen

- Logical Reasoning MahaYagya MBA CET 2022 PaperDokument7 SeitenLogical Reasoning MahaYagya MBA CET 2022 PaperShivam PatilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nitesh RijalDokument3 SeitenNitesh RijalNitesh RijalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sample IEODokument2 SeitenSample IEOPriyanka RoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The VERB HAVE as a main and auxiliary verbDokument7 SeitenThe VERB HAVE as a main and auxiliary verbKhumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- IMD StationsDokument15 SeitenIMD Stationschinna rajaNoch keine Bewertungen

- English Practice Book 4Dokument19 SeitenEnglish Practice Book 4akilasrivatsavNoch keine Bewertungen

- Life and Works of RizalDokument9 SeitenLife and Works of RizalMazmaveth CabreraNoch keine Bewertungen

- LEXICAL ITEM TYPESDokument5 SeitenLEXICAL ITEM TYPESririnsepNoch keine Bewertungen

- 11 2 ET V1 S1 - Introduction PDFDokument12 Seiten11 2 ET V1 S1 - Introduction PDFshahbaz jokhioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Updated Resume of Muhammad Naveed Ahmed 30032010Dokument2 SeitenUpdated Resume of Muhammad Naveed Ahmed 30032010EmmenayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Redfish Ref Guide 2.0Dokument30 SeitenRedfish Ref Guide 2.0MontaneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Angela Arneson CV 2018Dokument3 SeitenAngela Arneson CV 2018api-416027744Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ccbi Schools, Asansol & Kolkata SYLLABUS - 2018 - 2019 /CLASS - VIII English Language Text Book - Applied English (NOVA) First TermDokument14 SeitenCcbi Schools, Asansol & Kolkata SYLLABUS - 2018 - 2019 /CLASS - VIII English Language Text Book - Applied English (NOVA) First TermSusovan GhoshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Barren Grounds Novel Study ELAL 6 COMPLETEDokument113 SeitenBarren Grounds Novel Study ELAL 6 COMPLETEslsenholtNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assembly Language GrammarDokument3 SeitenAssembly Language GrammarJean LopesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Orca Share Media1558681767994Dokument11 SeitenOrca Share Media1558681767994ArJhay ObcianaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Detailed Lesson PlanDokument4 SeitenDetailed Lesson PlanAntonetteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Multiplication of DecimalsDokument30 SeitenMultiplication of DecimalsKris Ann Tacluyan - TanjecoNoch keine Bewertungen

- April 2022 (Not Including Easter)Dokument4 SeitenApril 2022 (Not Including Easter)Michele ColesNoch keine Bewertungen

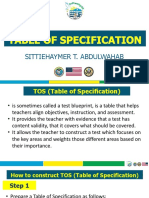

- Constructing a TOSDokument17 SeitenConstructing a TOSHymerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contemporary English VersionDokument3 SeitenContemporary English VersionJesus LivesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Course: CCNA-Cisco Certified Network Associate: Exam Code: CCNA 640-802 Duration: 70 HoursDokument7 SeitenCourse: CCNA-Cisco Certified Network Associate: Exam Code: CCNA 640-802 Duration: 70 HoursVasanthbabu Natarajan NNoch keine Bewertungen