Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Job Charactheristics and Stress

Hochgeladen von

Roxana VornicescuCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Job Charactheristics and Stress

Hochgeladen von

Roxana VornicescuCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Human Relations

http://hum.sagepub.com Rethinking job characteristics in work stress research

Kevin Daniels Human Relations 2006; 59; 267 DOI: 10.1177/0018726706064171 The online version of this article can be found at: http://hum.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/59/3/267

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

The Tavistock Institute

Additional services and information for Human Relations can be found at: Email Alerts: http://hum.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://hum.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations (this article cites 39 articles hosted on the SAGE Journals Online and HighWire Press platforms): http://hum.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/59/3/267

Downloaded from http://hum.sagepub.com by Vercellino Daniela on November 5, 2007 2006 The Tavistock Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Human Relations DOI: 10.1177/0018726706064171 Volume 59(3): 267290 Copyright 2006 The Tavistock Institute SAGE Publications London, Thousand Oaks CA, New Delhi www.sagepublications.com

Rethinking job characteristics in work stress research

Kevin Daniels

A B S T R AC T

In work stress research, consistent relationships between job characteristics and strain have not been established across methods for assessing job characteristics. By examining the methods used to assess job characteristics in work stress research, I argue that this is because different methods are assessing interrelated, yet distinct, facets of job characteristics: latent, perceived and enacted facets. The article discusses the implications for work stress research of differentiating these facets of job characteristics.

K E Y WO R D S

job characteristics measurements stress stressors

Within post-positivist approaches to organizational research, methods are seen as fallible and triangulation of results across methods is recommended (e.g. Cook & Campbell, 1979). But what happens if researchers presumptions about multi-method triangulation are wrong and different methods produce diverging results? What if different methods are assessing different yet interrelated phenomena? Could a critical examination of methods used evoke more insight and help develop more sophisticated approaches to research and theory? By examining methods used in research on work stress to assess the causes of strain, it is the aim of this article to illustrate how this might be so. The methods used in this arena are important for several reasons. First, many dominant theoretical models that guide work stress research accord psychosocial aspects of the work environment, known as job characteristics,

267

Downloaded from http://hum.sagepub.com by Vercellino Daniela on November 5, 2007 2006 The Tavistock Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

268

Human Relations 59(3)

with powerful causal status in determining health reactions, well-being and job satisfaction (e.g. Karasek & Theorell; 1990; Warr, 1987). Such environmental aspects are sometimes also known as stressors. Second, in spite of this assumed causal status, there is little evidence of triangulation of results across methods assessing job characteristics (Spector & Jex, 1991; Spector et al., 1988). Third, it is not clear whether the dominant method used to assess job characteristics the self-report questionnaire is better than other methods at assessing the causes of work-related strain (Morrison et al., 2003), or whether other methods actually assess the same constructs as selfreports (Spector, 1992, 1994). Noting weaknesses with how self-reports and the alternatives have been used, I propose a multi-level approach to conceptualizing job characteristics, comprising latent, perceived and enacted facets. This differentiation of job characteristics has implications for the methodologies stress researchers employ, the interpretation of results and the research questions they might begin to ask. The contributions of this article are twofold. First, and most generally, the article illustrates the need for researchers to think carefully on the consonance of theory, operational denitions and methods, lest attempts at triangulation of ndings lead to conicting results emerging in an area of research. Second, and more specically, the article shows that by carefully considering different approaches to measuring job characteristics, it is possible to develop a much richer appreciation of how organizational, social and individual factors combine to inuence what is experienced at work, and how this might relate to the processes that produce strain.

Self-reports and alternatives

Self-report measures of job characteristics have become the predominant means through which researchers link objective working conditions to psychosomatic and psychological strain. The assumption underlying their use is that perceptual measures reect, at least partially, the objective work environment: that is, the objective work environment is thought to cause perceptions of work.1 Some have argued that self-report measures can be problematic and their use can lead to unwarranted inferences from research into work, strain and health (e.g. Spector, 1994). Some of the major criticisms of self-report measures of job characteristics include: 1) Self-reports are subject to a number of biases, including transient mood effects, that systematically bias both reports of job characteristics and outcome measures (Brief et al., 1995; Spector, 1992);

Downloaded from http://hum.sagepub.com by Vercellino Daniela on November 5, 2007 2006 The Tavistock Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Daniels Rethinking job characteristics in work stress research

269

2)

3)

Self-reports and strain are mutually inuenced by trait affect or temperament failure to control for trait affect seriously undermines the strength of conclusions drawn from studies using self-reports (e.g. Brief et al., 1988); Self-reports of job characteristics are inuenced, through social interaction, by the attitudes, opinions and perceptions of others, rather than just the nature of the job itself (Salancik & Pfeffer, 1978).

There are several alternative strategies to simple self-reports of job characteristics. Examples are: a) using someone other than the incumbent to rate the incumbents job characteristics, such as managers, colleagues or researchers; b) using aggregate ratings of a job across several incumbents; c) using large databases or documents that contain information on the characteristics of a particular class of job; and d) assessing the impact of interventions designed to change job characteristics. The assumption underlying these strategies is that the objective work environment, at least to some extent, is reected in the assessments obtained. Others ratings of focal jobs (e.g. Fox et al., 1993). The logic here is that others reports are not subject to the same perceptual biases that limit the strength of conclusions drawn from studies using self-reports of job characteristics. Other raters could include managers, colleagues or members of the research team. However, manager and colleague ratings may become subject to other biases such as halo or horn effects thus introducing a new set of problems to interpreting results. For example, some evidence indicates that people exhibiting high strain are rated by others as being less attractive (Staw et al., 1994), which may generalize through stereotyping effects to awarding those people high ratings on undesirable job characteristics (e.g. make little effort to participate in decisions, self-impose heavy workloads). In this example, the horn effect has served to inate an association between measures of job characteristics and strain. Observers from the research team have also been used to assess job characteristics (e.g. Frese, 1985). One problem here is that independent observers rarely get the chance to spend extended periods with the target person. Unless every possible job behaviour is witnessed within the period of observation, then the observer is likely to miss some potentially important aspects of the job. Another limitation is that independent observers may not be allowed to witness clandestine or otherwise sensitive job activities a criticism that can also apply to managers and colleagues. Also, unless observers spend many months in an organization, they could remain largely unaware of the social context and perhaps misattribute some behaviour from their own frame of reference, rather than the frame of reference of those

Downloaded from http://hum.sagepub.com by Vercellino Daniela on November 5, 2007 2006 The Tavistock Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

270

Human Relations 59(3)

observed. For example, what passes for bullying or mobbing may be very different in a military context to that of a university, and might vary from person to person. Perhaps the most important limitation is that independent observers are only able to observe manifest behaviour such as hours spent in work that are just some of the elements that a job comprises. Independent observers are less likely to be able to obtain an accurate picture of cognitive processes such as planning and decision-making yet such cognitive activity might be critical to how job characteristics such as complexity and autonomy come to be. This criticism also applies to managers and colleagues ratings. What we can be sure of, however, is that rating by observers whether managers, colleagues or researchers represents someones perception of the focal job. These perceptions are unlikely to reect cognitive activity at all accurately and possibly not reect sensitive activities or activities incumbents keep hidden for other purposes. Aggregate ratings. Another approach to remove biases inherent in selfreports is to aggregate ratings from several individuals, all in the same job (e.g. Vahtera et al., 1996). The assumption underlying aggregation is that variations in perceptions of jobs will be cancelled out (Jones & James, 1979), therefore reducing the impact of biases associated with particular individuals. Jones and James provide four criteria for justifying aggregation: (a) signicant differences in aggregated or mean perceptions across different organisations or subunits; (b) interperceiver reliability or agreement; (c) homogeneous situational characteristics (e.g., similarity of context, structure, job type, etc.); and (d) meaningful relationships between the aggregated score and various organisational, subunit, or individual criteria. (Jones & James, 1979: 208) Criteria a) and b) can be demonstrated empirically in any study, through analysis of variance techniques and correlational indices of interrater reliability respectively. Criterion c) can be justied through examining people with the same contractual status, job descriptions, etc. However, the greatest question concerns the theoretical interpretation of results inherent in criterion d). If a signicant relationship is found between an aggregated measure of work demands and individual measures of strain, it cannot be concluded that objective work demands inuence an individuals strain. There exist commonalties of perception in any social grouping (Thompson et al., 1990), and perceptions of job characteristics might be conditioned by social information processing to some extent (Salancik & Pfeffer, 1978).

Downloaded from http://hum.sagepub.com by Vercellino Daniela on November 5, 2007 2006 The Tavistock Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Daniels Rethinking job characteristics in work stress research

271

Moreover, there is also evidence that affective tone in work groups is linked to convergence in trait affect in work groups (George, 1990), indicating that aggregation might further compound some of the biases inherent in selfreports of job characteristics. It is then possible that any association between strain and aggregated measures of job characteristics reects a shared perception of job characteristics, rather than any objective reality. This is not to say that this approach is meaningless, only that aggregated measures by themselves cannot help construct unambiguous interpretations of results concerning objective job characteristics. It might be argued that where there is no direct contact between incumbents such as where they are situated in different locations or on different shifts then this social information processing explanation may not be valid (Semmer et al., 1996). However, common institutional factors present at national, sector, industry and organizational levels will serve to condition perceptions within physically separated jobs (Scott, 1995). For example, selection of similar people, and then socialization into particular job roles through the actions of others and common experiences (e.g. through contact with managers, trades unions, trainers, and educators), inculcates and reinforces particular perceptions of work (Schneider, 1987). This socialization process might be especially strong in institutionalized arenas with strong legislation, strong organizational cultures and proscribed training or education (such as medical professions, accountancy, strongly unionized industries; DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). Using large databases or documents. Another approach is to determine job characteristics from documentary evidence associated with job titles. In the United States, the Dictionary of Occupational Titles (DOT) and, more recently, the O*NET databases allow researchers to match job titles to a number of job characteristics in an extensive database of job analyses (Roos & Treiman, 1980, used by Spector & Jex, 1991; Spector et al., 1995). Whilst attractive given the rigour with which such databases are assembled and their breadth of coverage, there exist problems with these methods too. First, job analyses may quickly become out of date, especially in current economic environments of hypercompetition, accelerated innovation, frequent organizational change and rapid developments in information technology. However, perhaps the greatest limitation is that national databases represent the occupation not the job that is local peculiarities of a job are ignored, especially changes individuals themselves make to their job characteristics (Parker et al., 2001; Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). This makes it difcult to draw unambiguous inferences about the stressors associated with a particular job in a particular organization.

Downloaded from http://hum.sagepub.com by Vercellino Daniela on November 5, 2007 2006 The Tavistock Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

272

Human Relations 59(3)

A related approach to determine job characteristics is for job descriptions to be rated by expert raters (either job incumbents not sampled, HR managers or the research team, e.g. Spector et al., 1995). The same problems of inferring cognitive processes and social norms could apply here as to reports from managers, colleagues or observers, as could problems concerning job descriptions becoming out of date if a given context changes. Therefore, databases and documents do not necessarily provide pure reections of objective job characteristics. Rather such methods may better reect a job as it has become institutionalized in documentary form, rather than how a job is evolving in the present. Interventions. One solution to problems with self-report, other-report, aggregation, databases and documentary measures is to examine interventions only. In this approach, a structural, managerial or technological change is made in an organization that is hypothesized to change job characteristics so as to make the job more psychosocially hygienic (e.g. increase levels of job control; Wall et al., 1986). If strain reduces, then it could be concluded this is a result of the changes in job characteristics bought about by organizational change. Notwithstanding problems of design associated with intervention studies (Cook et al., 1990), there are at least three other problems with this approach. First, from a practical point of view, some other assessment of job characteristics is needed. Prior to the intervention, assessment of job characteristics is needed to determine the levels of aversive job characteristics present in the environment, and therefore which job characteristics need to be altered through intervention. Then, subsequent to the intervention, assessment is needed to ensure that the intervention changed the target job characteristics (i.e. a manipulation check). Without these data, it would be impossible to know whether the intervention changed what it was supposed to and, therefore, whether correct inferences are being drawn. Therefore, even if researchers were to concentrate on interventions, they would still be a practical need to assess job characteristics independent of interventions. Second, interventions can change many job characteristics and personal skills. For example: the introduction of semi-autonomous work teams could increase support from co-workers, work autonomy and work variety. Further, in this example, Cotton (1993) considers training of workers to be an important factor in the success of semi-autonomous work teams. In these circumstances, it would be impossible to infer whether changes in strain could be attributed to changes in levels of particular job characteristics, training or some combination of job characteristics and training. Third, organizational changes are an obtrusive way of researching work stress. Without rst conducting unobtrusive research in natural

Downloaded from http://hum.sagepub.com by Vercellino Daniela on November 5, 2007 2006 The Tavistock Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Daniels Rethinking job characteristics in work stress research

273

settings, there would be no ecologically valid and empirical basis for the intervention. As such, the chances of an intervention producing unintended and harmful consequences would be increased. This raises serious questions about the ethics of this approach in isolation from other research.

Conclusions on alternative strategies: Why triangulation does not work

If all methods are awed to some degree, then what strategies are available to researchers? Perhaps the most commonly prescribed strategy is that of triangulation if a job characteristic produces an association with strain across several different measuring techniques, then it can be reliably inferred that there is an association between the job characteristic and strain. That is, because methods measure the relevant phenomena imperfectly (see, for example, Frese & Zapf, 1988), by using several independent methods in a study or research programme, the errors in measurement can be assumed to mitigate each other (Cook & Campbell, 1979). Techniques exist for triangulation of results, both within studies (multitrait-multi-method matrices, latent variable modelling, e.g. Bagozzi & Yi, 1990) and between studies (meta-analysis, e.g. Hunter & Schmidt, 1990). Triangulation of results might work only if different methods produce the same results. If different methods were to produce contradictory results, then any benets of triangulation are lost. Further, if triangulation occurred only in some circumstances (only for some job characteristics, some jobs or some organizational settings), and not in others pursuing a strategy of triangulation would limit severely the scope of theory and practical application of work stress research. What is clear is that triangulation across data sources is often difcult (e.g. Sanchez et al., 1997). In a study using latent variable analysis to aggregate multiple self-reports and multiple observer ratings of job characteristics and strain (Semmer et al., 1996), the best tting models indicated differences in how observers and incumbents rated the characteristics of focal jobs. Other studies have indicated that different methods of assessing job characteristics produce different associations with indices of strain (Morrison et al., 2003; Spector & Jex, 1991). In one study, self-reports of work control and human resource managers ratings of incumbents work control were not highly correlated (r = 0.41), yet both contributed independently to predicting subsequent indicators of coronary heart disease (Bosma et al., 1997). Even in the most controlled settings of a laboratory study, Jimmieson and Terry (1997) were unable to triangulate ndings from objective manipulations of the features of

Downloaded from http://hum.sagepub.com by Vercellino Daniela on November 5, 2007 2006 The Tavistock Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

274

Human Relations 59(3)

a simulated job task with those of perceptual measures taken during the course of the experiment. Of course, it could be argued that discrepancies within and between studies are due to differential predictive validity of measures of job characteristics, as well as imperfect validity of measures of strain. However, even where triangulation is possible, any results might be theoretically meaningless. For example, triangulated evidence of an association between job control and strain merely tells us that there is an association not why there is an association. Perhaps the best approach is to be clear on the kind of information provided by each approach to measuring job characteristics. This might help to achieve a better level of explanation and help to avoid any difculties if triangulation does not occur. That is, because different methods might be assessing different phenomena, we need to examine more closely the construct validity of different methods. From above, it is clear that it is possible to collect information: a) on peoples perceptions of their own job characteristics (self-reports); b) on peoples perceptions of others job characteristics (other-reports); c) on collective perceptions of job characteristics (aggregate reports); and d) on the more institutionalized aspects of job characteristics (databases cross-referenced across documentary data on job titles, analysis of job descriptions, interventions). This might lead us to suppose that job characteristics comprise of many different subjective and institutionalized facets that might be interrelated in some way.

Differentiating facets of job characteristics

It has been suggested that much research on job characteristics and strain gives the impression that people are more passive receivers of information from the environment than we know is the case (Briner et al., 2004). It is the idea that people are active in interpreting their jobs, and consequently in shaping their jobs (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001), which leads to considering an aspect of job characteristics hardly mentioned in the literature that is enacted job characteristics. By this, it is meant that people are likely to enact those job characteristics that they perceive are part of their job, should be part of their job or otherwise might help them achieve something at work (Weick, 1995). For example, a person, who believes that they have enough autonomy over work to reschedule some tasks, may enact this autonomy by rescheduling tasks in such a way to spend more time on aspects of work they enjoy and avoid undesirable features of work. A person, who believes a supervisor would offer sympathy, might be more likely to conde in that

Downloaded from http://hum.sagepub.com by Vercellino Daniela on November 5, 2007 2006 The Tavistock Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Daniels Rethinking job characteristics in work stress research

275

supervisor as a source of social support. As well as enacting desirable job characteristics people can also enact undesirable job characteristics. For example, associations between achievement-oriented pressured type A personality and workload (Spector & OConnell, 1994) could be explained by type As taking on more workload to achieve ambitious career goals and status symbols. The job incumbent is not the only person capable of enacting job characteristics. Given their power over others (Braverman, 1974), it is possible that managers enact the job characteristics that they believe are characteristics of a given persons job (for example, by asking subordinates to perform certain tasks, achieve certain objectives, prescribing ways in which tasks are to be performed or providing levels of resources that constrain how subordinates can meet work objectives). Professional and organizational norms are also likely to reect on how colleagues and subordinates enact the working environment, in such a way as to encourage or proscribe the enactment of certain job characteristics (Scott, 1995). Of course, managers, colleagues and subordinates can enact positive job characteristics (such as support, allowing autonomy, participation) or they can enact negative job characteristics (such as creating a greater workload, role conict). It is possible, then, to differentiate between enacted job characteristics what actually happens and perceived job characteristics (self-perceptions, other perceptions). To some degree, enacted job characteristics are a product of one or more persons perceptions of what a job entails. However, earlier I referred to institutionalized elements of job characteristics. These are embedded in the contractual elements of job descriptions, technology, organizational structures and the networks of social relationships embedded in job design, organizational structures and reporting relationships. These elements could serve to limit what is possible for various people to enact within a particular job (for example, we might expect: professional workers to report greater autonomy than non-professional workers; assembly line work to limit job autonomy, skill use and variety; workers in matrix organizations to experience greater role ambiguity and conict). Since these institutionalized elements serve to proscribe limits they are referred to as latent job characteristics. On the basis of this discussion, it is possible, then, to dene three different facets of job characteristics as follows: Latent job characteristics2 are those aspects of job characteristics embedded in organizational and technical processes. They are independent of activity or perception, but remain dormant unless there is an incumbent doing a job.

Downloaded from http://hum.sagepub.com by Vercellino Daniela on November 5, 2007 2006 The Tavistock Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

276

Human Relations 59(3)

Perceived job characteristics are someones generalized perceptions of job characteristics. Enacted job characteristics3 are the events that job incumbents, and those that come into contact with the incumbent, enact. They comprise the emergent and dynamic characteristics of the job.

Latent job characteristics

Latent job characteristics comprise the institutional and technological pressures that inuence work, and are reected in techniques usually considered to be furthest from the perceptions and actions of individuals in work and therefore are often considered to be the most objective indicators of job characteristics (Spector & Jex, 1991). They might include details of contract lengths or notice periods as indicators of job security, contractual hours rather than actual hours worked as an indicator of work demands or machine-paced work as an indicator of lower job autonomy. Suitable methods to assess latent job characteristics might be analysis of large databases such as the O*NET, or analysis of documents such as job descriptions, employment contracts, operating manuals and organizational charts. Latent job characteristics might also be inferred, at least partially, from interventions that change job descriptions, employment contracts, operating manuals, organizational structures, work processes or technology. However, latent job characteristics, in themselves, are unlikely to provide the basis of explaining links between work and strain. Evidence indicates it is factors much closer to individuals that have the closest links to strain (Lazarus, 1999; Suh et al., 1996).

Perceived job characteristics

Several kinds of observers can form judgements and make reports about the characteristics they usually associate with a job. Therefore, many current measures of job characteristics used in survey research reect the generalized perceptions of incumbents, line managers, co-workers, some aggregate thereof or researchers depending on who is doing the rating. With the exception of researchers perceptions, links might be expected between latent job characteristics and perceived job characteristics. The rst way in which latent job characteristics could inuence perceived job characteristics might be through direct judgement. Here, individuals make inferences concerning how the nature of work is dictated by factors such as technology, organizational processes and employment

Downloaded from http://hum.sagepub.com by Vercellino Daniela on November 5, 2007 2006 The Tavistock Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Daniels Rethinking job characteristics in work stress research

277

contracts. That is, factors that might serve to inuence incumbents and others perceptions of work characteristics include production or service delivery technology, extent of teamworking, information systems, performance management practices, reward structures and job descriptions (see, for example, Parker et al., 2001). Indeed, changes in factors indicative of latent job characteristics have been found to be associated with subsequent changes in self-reports of job characteristics (Parker, 2003; Parker et al., 2002). Clearly, shared experience could lead to commonality in perceptions of job characteristics amongst a group. However, there are other indirect routes by which latent job characteristics might inuence perceived job characteristics and promote convergence of perceptions. These concern observation and discussion with others. For example, during socialization into a new job, incumbents may come to judge levels of job characteristics by discussion with line managers (Ostroff & Kozlowski, 1992). Further, shared stories and discourses about work that reinforce a shared perception of that job may be passed around incumbents with the same job title, their line managers and others with whom they come into contact (Feldman & Rafaeli, 2002). In this way, others perceptions may come to inuence an incumbents perception of his or her job. Others perceptions may come to converge with incumbents perceptions in a manner more or less independent of latent job characteristics too. This might occur through socialization practices that reect shared training, especially where early training is carried out in organizations, such as universities, largely independent of the eventual working environment (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). It might also occur where powerful groups of workers with common interests are able to claim the right to certain job characteristics, such as skill use, regardless of job descriptions, technology and other factors related to latent job characteristics (Noon & Blyton, 1997). These groups may then be able to protect that claim and inuence perceptions through regulations that place restrictions on who is allowed to do a job, as has been the case for some trades unions and professional institutions (Noon & Blyton, 1997). The perceptions of researchers are unlikely to be inuenced directly by others perceptions. Usually, researchers ratings are based on what researchers can observe. Thus reecting, partially at least, job characteristics as they are enacted. We might expect some degree of overlap between researchers ratings of job characteristics and those of incumbents, coworkers and managers. This is because job characteristics as they are enacted are driven by the perceptions of those with direct inuence on a particular job: incumbents, co-workers and line managers (Weick, 1995). That is,

Downloaded from http://hum.sagepub.com by Vercellino Daniela on November 5, 2007 2006 The Tavistock Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

278

Human Relations 59(3)

incumbents, co-workers and managers enact those job characteristics that they attribute to the incumbents job.

Enacted job characteristics

These are events that reect jobs as they happen. It is these events that are proximal to the individuals experience of strain (Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996). For example, Suh et al. (1996) found that more recent events have a stronger effect on strain than more distant events. Pillow et al. (1996) found that the impact of major life events on strain was mediated by daily stressful events caused by the disruption of the life events. Further, work events are considered the basis upon which several cognitive processes come to inuence affective experience at work (Daniels et al., 2004). Hence, I consider enacted job characteristics to be the locus of appraisals and coping that inuence strain, not enduring perceptions of work or structural, technological or contractual features of work. That is, I consider that the intraindividual processes that produce strain within people do so because those processes are inuenced by enacted job characteristics. Enacted job characteristics can take several forms. They can be potentially observable comprising behaviours or discourse. A behavioural example might be using several tools to complete a task as enacted skill use. For discourse, an example might be voicing an objection to others plans, as an example of participation in decision-making. Note, even clandestine activities that are behavioural or discursive are potentially observable by someone other than the incumbent. Enacted job characteristics might also be cognitive, and therefore not amenable to direct external observation, whatever the circumstances. An example of cognitive enactment might be complex problem-solving, as an example of demands. Enacted job characteristics can be enacted by the incumbent, or by the actions of others. For instance, role ambiguity can be enacted by managers setting tasks with no clear objectives. It might be supposed that latent job characteristics in seemingly restricted environments, such as machine-paced manufacturing, have stronger relations to other facets of job characteristics than in less restricted environments, such as managerial work. However, Briner et al. (2004) argue that even in restricted environments, people still enact the environment and have some inuence over the characteristics of their work (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). The idea of enacted job characteristics echoes episodic events approaches to work and affect (Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996), where the interpretations of specic events as they happen cause changes in affect, and changes in affect subsequently inuence attitudes such as job satisfaction. More widely, concentrating on job characteristics as enacted events allows

Downloaded from http://hum.sagepub.com by Vercellino Daniela on November 5, 2007 2006 The Tavistock Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Daniels Rethinking job characteristics in work stress research

279

us to study the processes by which organizational life inuences individuals and how individuals act within organizational contexts (Peterson, 1998). This is not to say that generalized perceptions or structural, technological or contractual features of work are not without inuence on strain. Rather, because enacted job characteristics are the locus of intra-individual processes that produce strain, enacted job characteristics may mediate the relationships between perceived job characteristics, latent job characteristics and strain hence perhaps offering an explanation for associations between indicators of perceived or latent job characteristics and strain. As an example of the inter-relationships between latent, perceived and enacted job characteristics, consider a matrix organization consisting of overlapping project teams. Here there is great potential for role conict where an individual belongs to more than one project team (latent job characteristic). Incumbents previous experience of working in such structures plus discussion between them and their managers might lead to the perception of role conict within the job (perceived job characteristic). Because managers may then consider role conict as an inevitable consequence of working in such organizational structures, managers may then ask workers to complete tasks to deadlines without checking on the progress of other tasks against other deadlines, producing role conict (enacted job characteristic) which is subsequently appraised as stressful. Some mutual inuence between perceived and enacted job characteristics might be expected. Mere enactment of a job characteristic might alter a persons view of his/her work (Weick, 1995). Extrapolating from the role conict example just given repeated exposure to conicting priorities given by managers may create heightened perceptions of role conict. However, where there is opportunity to observe or discuss work with others, then others perceptions of the focal persons job might change too. This is perhaps likely to be strongest where enactment of job characteristics is routinized, so that there is more opportunity for shared understandings to emerge (Feldman & Rafaeli, 2002). For example, the routinized timetables and breaks in schools provide the perceptual impetus for discussing the demands imposed by school timetables, and visiting the staff room at breaktimes provides a routinized forum for discussing these issues. Perhaps too, where there is mutual dependence between workers to perform tasks, then perceptions of others job characteristics might develop that allow individuals to enact job characteristics in a manner that is heedful of others work (Weick & Roberts, 1993). For instance, in self-regulating work teams, clearly specifying ones own tasks and estimated time of completion of those tasks might enact role clarity for colleagues. Supposing interdependence of enacted job characteristics and various actors perceived job characteristics allows less restrictive assumptions about

Downloaded from http://hum.sagepub.com by Vercellino Daniela on November 5, 2007 2006 The Tavistock Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

280

Human Relations 59(3)

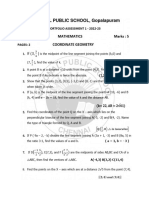

relations between the work environment and measurements than has largely been the case hitherto. As noted earlier, using perceptual measures has often entailed assuming/presuming the work environment causes perceptions. Positing the existence of enacted job characteristics means perceptions might cause events in the work environment, and events in the work environment might cause perceptions. Table 1 summarizes the features of latent, perceived and enacted job characteristics. Figure 1 is a representation the relationships between enacted, perceived and latent job characteristics that have been illustrated in the preceding paragraphs. Strain is included in the model as a consequence of the relationships between these different facets of job characteristics, with enacted job characteristics as the most proximal cause of strain. However, this relationship is shown as conditional, because the processes linking specic forms of strain to job characteristics are complex (e.g. Daniels et al., 2004). Therefore the detail of these relationships is beyond the scope of the current model. Figure 1 is an illustration of the potential gain in theoretical richness by expanding the conception of job characteristics to differentiate enacted,

Table 1 Summary of facets of job characteristics

Facet Latent job characteristics Key features Institutional, social and technological pressures that inuence work Sub-classes Example methods National job databases Analysis of job descriptions, employment contracts, operating manuals and organizational charts Interventions Survey methods that rely on individuals rating the extent to which they agree a statement describes a target job

Perceived job characteristics

Generalized perceptions of how a job usually is

Enacted job characteristics

Events and activities in the job as they happen

Perceptions of own job Line managers perceptions Co-workers perceptions Researchers perceptions Behavioural Discursive Cognitive

Self-reports of events or activities within specic time frames, using, for example, daily diary methods

Downloaded from http://hum.sagepub.com by Vercellino Daniela on November 5, 2007 2006 The Tavistock Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Daniels Rethinking job characteristics in work stress research

281

Managers a nd colleagues perceptions of job

Latent job characteristic

Enacted job characteristic

Strain

Incumbents perceptions of job

Researchers perception of job

Indicates a potentially weaker or conditional relationship

Figure 1

Possible relationships between facets of job characteristics

perceived and latent facets of job characteristics. The strength of relations suggested in Figure 1 might vary in strength according to the nature of the job characteristic under investigation (e.g. are the relations shown in Figure 1 stronger for skill use and autonomy, than for work demands?). The differentiation of facets of job characteristics, and the mapping of possible relations among them, raises implications for both methods and the kinds of research questions researchers might choose to investigate. We turn to these implications next.

Implications for methods

How then should enacted, perceived and latent job characteristics be measured? Self-reports are obviously necessary to determine perceived job

Downloaded from http://hum.sagepub.com by Vercellino Daniela on November 5, 2007 2006 The Tavistock Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

282

Human Relations 59(3)

characteristics. Suitable measures might include many of the popular measures for assessing job characteristics, with Likert-type scaled responses for assessing generalized levels of agreement with statements describing job characteristics over an unspecied time span. Aggregated measures of this kind may serve to identify coherent collective perceptions, should researchers be interested in the inuence of a social group as a whole on individuals perceived and enacted job characteristics. Researchers might assess latent job characteristics by examining various forms of organizational documents and processes, for example: job descriptions and contractual arrangements; structural network relationships with co-workers, subordinates and supervisors; examination of the jobs place in the organizational structure; and how technology is used in the job. Researchers might then assess each source of data for the extent to which it provides evidence of the presence or absence of pre-dened job features. For example, the latent job characteristics for role conict might be assessed by looking at the number of reporting relationships for an individual (from the job description), the number of project teams or committees that individual belongs to (from the organizational chart), the number of processes that individual is responsible for (from examining production or service delivery manuals). To measure enacted job characteristics, self-reports may also be the best strategy. However, the kind of self-reports used would be different from those used to assess perceived job characteristics. There are a number of arguments for this point of view. These can be divided into three main areas: a) other methods are unsuitable; b) self-reports are commonly used in coping research; c) in the right circumstances, self-reports can minimize bias. The argument that other methods are unsuitable is essentially a practical argument. Enacted job characteristics are dynamic and activity-oriented so measures should tap these features. Clearly, documentary and technostructural assessments are unable to achieve this. As mentioned earlier, ratings by external observers are subject to framing biases and cannot assess hidden or cognitive activity well. Moreover, as jobs become more knowledge intensive, the potential to use external observers is reduced. The argument that self-reports are used in coping research is essentially an argument of precedent. At least since the development of the Ways of Coping Checklist (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), self-report methods have been the standard way of assessing coping. This is because coping includes cognitive and hidden activity, as well as overt behaviour and discourse features shared with enacted job characteristics. It may be reasonable, then, to expect that people can provide accurate assessments of the work events they encounter. However, self-reports can be inaccurate and researchers need to pay close attention to the nature of self-report methodologies and the psychometric properties of instruments.

Downloaded from http://hum.sagepub.com by Vercellino Daniela on November 5, 2007 2006 The Tavistock Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Daniels Rethinking job characteristics in work stress research

283

Therefore, the strongest argument for self-reports of enacted job characteristics is that self-reports can provide accurate assessments of enacted job characteristics, if designed properly and used in the right circumstances. To minimize bias, self-reports used to assess enacted job characteristics should concentrate on specic events, be clearly worded and require recall only over a short, recent and specied time frame (Frese & Zapf, 1988). The best period may be to report on current activity or within the past few hours. Evidence indicates people may exaggerate how proactive they are if the time frame becomes too great (Stone et al., 1998). Because of their ability to capture processes close to when they happen (Bolger et al., 2003), the best methods to develop and test theory around enacted job characteristics might be event sampling methods such as computerized momentary assessments or daily diary studies. This means that self-report measures of enacted job characteristics are best employed in short-term studies and therefore in research on rapidly changing aspects of strain such as affect (Weiss et al., 1999). However, event sampling methods are not straightforward, and researchers need to take steps to eliminate potential biases that can affect event sampling studies if short-term assessments of enacted job characteristics are to be accurate (see, for example, Bolger et al., 2003). Further steps need to be taken to ensure designs can rule out alternative explanations for ndings. For some health outcomes (such as clinical levels of depression), shortterm assessments of enacted job characteristics may not be suitable, as the causal process is too extended. Instead, more traditional measures of job characteristics may need to be used. Whilst such studies may not be able to offer unambiguous theoretical statements of specic causal processes, if supplemented with short-term studies of the processes involved in the subclinical stages of long-term health outcomes, then more precise theoretical statements might be possible. For example, affective reactions to work, which are highly dynamic (Parkinson et al., 1995), might mediate the link between work characteristics and longer-term indicators of strain (Robinson, 2000; Spector & Goh, 2001). In these circumstances, event sampling studies can be used to examine the affective reactions to work presumed to mediate between job characteristics and more slowly changing forms of strain. Similarly, short-term and dynamic physiological reactions, such as heart rate, can be monitored by portable devices, and so can be assessed in studies looking at job characteristics and physical strain. Notwithstanding all these considerations, examining a complete set of relationships between the latent, perceived and enacted aspects of just one job characteristic, plus assessing relationships with strain, might seem very labour intensive, since data need to be collected from several sources and the validity and reliability of three sets of measures for each job characteristic

Downloaded from http://hum.sagepub.com by Vercellino Daniela on November 5, 2007 2006 The Tavistock Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

284

Human Relations 59(3)

need to be established. Moreover, if quantitative methods are to be used in event sampling studies, statistical methods are needed that can cope with complex multi-level data with a time series element. Multi-level regression and multi-level structural equations modelling methods would seem appropriate (e.g. Bentler, 2003; Muthn & Muthn, 1998).

Implications for research questions

The differentiation of latent, perceived and enacted job characteristics does not just have implications for supplementing more traditional approaches to assessing job characteristics with event-based measures. This differentiation shifts the level of explanation from one concerned with explaining variance in concurrent levels of strain or subsequent changes in strain, to a much richer, dynamic and multi-level view of job characteristics. In this dynamic view, enacted job characteristics are at the juncture between the cognitive interpretation and coping processes that inuence strain and the social and organizational processes from which enacted job characteristics emerge. Put another way, identifying enacted job characteristics neither privilege work and organizational approaches nor cognitive and perceptual approaches to understanding strain. Rather, the differentiation provides one way of thinking about how the two approaches might be reconciled. There are novel research questions that arise too. The rst pertains to the empirical status of the different facets of job characteristics if latent, perceived and enacted job characteristics represent different phenomena, then evidence of their differentiation should be produced. One way of doing this might be through factor analysis. For example, multiple indicators of latent job autonomy should correlate more closely with each other than multiple indicators of perceived and enacted autonomy. In turn, multiple indicators of perceived autonomy should correlate most closely with each other and indicators of enacted autonomy correlate most closely with other indicators of enacted autonomy. In this case, multiple indicators of latent job autonomy, multiple indicators of perceived job autonomy and multiple indicators of enacted job autonomy should produce three distinct factors if subjected to factor analysis. On top of this requirement, if event sampling studies are to be used to assess enacted job characteristics, then variation in levels of enacted job characteristics should be evident across short time intervals. However, recent evidence does suggest meaningful daily variability in job characteristics such as demands, skill use, control and support (Butler et al., 2005; Daniels & Harris, 2005). If the different facets of job characteristics are empirically distinct, then

Downloaded from http://hum.sagepub.com by Vercellino Daniela on November 5, 2007 2006 The Tavistock Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Daniels Rethinking job characteristics in work stress research

285

the extent and reasons for interrelations between the different facets become interesting questions. I have already discussed some relations, as illustrated in Figure 1, and surfaced explanations for these relations. However, investigating such interrelations could also illuminate the process of interventions. For example, in contexts where collective perceptions of job characteristics exert a strong inuence on individual perceptions and hence enacted job characteristics, these collective perceptions might represent a source of inertia that acts against enhancement of the experience of work through job redesign. That is, the latent job characteristic might have changed, but the practical intervention fails because the perceived and enacted facets of the job characteristic have not changed sufciently.

Conclusion

By considering what various measures of job characteristics actually assess, it is possible to differentiate three aspects of job characteristics perceived, latent and enacted. Such a differentiation means that researchers need not make restrictive assumptions about the relations between theoretical constructs and measurements. Rather measurements can be assumed to measure what they actually do measure. This does not necessarily invalidate previous ndings in the stress research arena. However, this research might now be open to a new level of interpretation using a theoretical classication that might explain divergence across methods, and the strength of interrelations between the same job characteristic assessed using different methods. Further, a series of interesting research questions might arise from relaxing the assumptions made in much stress research to date. Assessing enacted job characteristics allows us to study the uid dayto-day experience of work as it is acted out. This serves to strengthen the construct and ecological validity of research, because assessments reect the on-going and dynamic causal processes that inuence strain (Lazarus, 1999; Tennen & Afeck, 2002; Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996). Differentiating enacted job characteristics from other facets of job characteristics also enables work stress researchers to go beyond, but not exclude, job design theories as a basis for explanation. This differentiation links work stress research to wider debates in management and organization theory concerned with the uidity and multiple layers of organizations and work. On the one hand, introducing notions of dynamism in job characteristics links to debates concerning, for example, the correct unit of analysis to understand work and organizations (Peterson, 1998), and how organizational processes come to be (cf. Minztberg & Waters, 1985). On the other

Downloaded from http://hum.sagepub.com by Vercellino Daniela on November 5, 2007 2006 The Tavistock Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

286

Human Relations 59(3)

hand, linking job characteristics to embedded organizational processes and perceptions provides a theoretical footing for understanding the links between the institutional and economic factors, at the levels of nation-state, industry and organization, that inuence job design and the perception of work (Hall & Soskice, 2001; Scott, 1995). Further, by differentiating amongst different aspects of job characteristics, there is a rmer and more fertile theoretical grounding for the assessment of job characteristics and explaining how different facets of job characteristics contribute directly and indirectly to strain. One contribution of this article, then, is to illustrate how careful consideration of methods can provide a better basis for interpreting results produced by different methods and, hence, help explain why triangulation does not occur. Another contribution is that, at least in the area of work stress research, such a careful consideration of methods can enhance theoretical richness and suggest new avenues for research. This theoretical richness comes from considering job characteristics, not as separate from or as distinct inuences on work events, but as phenomena that comprise interrelated institutional, technological and perceptual facets together with events that are the product of actors agency. This approach favours the use of dynamic methods capable of capturing processes instead of or as well as variance, and suggests new ways of interpreting the ndings of varianceoriented research designs. The articles contribution may extend beyond the application of new ways of conceptualizing job characteristics to interpreting research ndings. As noted above, considering different facets of job characteristics and how they interrelate enables us to consider how enacted job characteristics may be changed or impeded by organizational factors and shared and individual perceptions. Arguably, this might lead to more sophisticated approaches to intervention that consider simultaneously both the perceptual and organizational levers and barriers to changing the experience of job characteristics.

Notes

1 In much work stress research, self-report methods require participants to rate the characteristics of their work. It is these ratings we concentrate on here. This article does not concern itself with methods to assess the interpretative processes by which a person appraises a job characteristic to be more or less unpleasant or stressful. Rather, in this article, I concentrate on methods that seek to assess the reality of job characteristics without further interpretation of their desirability. The term should not be confused with latent variables, familiar from structural equations modelling, that are unobservable variables indexed by a set of observable variables.

Downloaded from http://hum.sagepub.com by Vercellino Daniela on November 5, 2007 2006 The Tavistock Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Daniels Rethinking job characteristics in work stress research

287

Enacted job characteristics are events as they happen, rather than the appraisal of those events. It is possible for people to enact job characteristics to full some purpose. For example, job autonomy or social support can be enacted to help cope with other aversive enacted job characteristics, by facilitating problem-focused coping, avoidance or emotion-focused coping (Daniels & Harris, 2005). In this sense, enacted job characteristics can be a coping behaviour, used to full some coping function (Lazarus, 1999). However, enacted job characteristics are a much wider concept, encompassing events enacted for whatever purpose by job incumbents and others that come into contact with the incumbent.

References

Bagozzi, R.P. & Yi, Y. Assessing method variance in multitrait-multimethod matrices: The case of self-reported affect and perceptions at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 1990, 75, 54760. Bentler, P.M. EQS V6.1 for Windows Beta Build 51. Chicago, IL: Multivariate Statistical Software Incorporated, 2003. Bolger, N., Davis, A. & Rafaeli, E. Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annual Review of Psychology, 2003, 54, 579616. Bosma, H., Marmot, M.G., Nicholson, A.C., Brunner, E. & Stansfeld, S.A. Low job control and risk of coronary heart disease in Whitehall ii (prospective cohort) study. British Medical Journal, 1997, 314, 55865. Braverman, H. Labor and monopoly capital: The degradation of work in the twentieth century. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1974. Brief, A.P., Burke, M.J., George, J.M., Robinson, B.S. & Webster, J. Should negative affectivity remain an unmeasured variable in the study of job stress? Journal of Applied Psychology, 1988, 73, 1938. Brief, A.P., Houston Butcher, A. & Roberson, L. Cookies, disposition, and job attitudes: The effects of positive mood inducing events and negative affectivity on job satisfaction in a eld experiment. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Making Processes, 1995, 62, 5562. Briner, R.B., Harris, C. & Daniels, K. How do work stress and coping work? Toward a fundamental theoretical reappraisal. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 2004, 32, 22334. Butler, A.B., Grzywacz, J.G., Bass, B.L. & Linney, K.D. Extending the demands-control model: A daily diary study of job characteristics, work-family conict and work-family facilitation. Journal of Occupational & Organizational Psychology, 2005, 78, 15569. Cook, T.D. & Campbell, D.T. Quasi-experimentation: Design and analysis issues for eld settings. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally, 1979. Cook, T.D., Campbell, D.T. & Peracchio, L. Quasi experimentation. In M.D. Dunnette & L.M.Hough (Eds), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, 2nd edn, vol. 1. Palo Alto, CF: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1990, pp. 491576. Cotton, J.L. Employee involvement. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1993. Daniels, K. & Harris, C. A daily diary study of coping in the context of the job demandscontrol-support model. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 2005, 66, 21937. Daniels, K., Harris, C. & Briner, R.B. Linking work conditions to unpleasant affect: Cognition, categorisation and goals. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 2004, 77, 34364. DiMaggio, P.J. & Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational elds. American Sociological Review, 1983, 48, 14761.

Downloaded from http://hum.sagepub.com by Vercellino Daniela on November 5, 2007 2006 The Tavistock Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

288

Human Relations 59(3)

Feldman, M.S. & Rafaeli, A. Organizational routines as sources of connections and understandings. Journal of Management Studies, 2002, 39, 30931. Fox, M.L., Dwyer, D.J. & Ganster, D.C. Effects of stressful job demands and control on physiological and attitudinal outcomes in a hospital setting. Academy of Management Journal, 1993, 36, 289318. Frese, M. Stress at work and psychosomatic complaints: A causal interpretation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 1985, 70, 31428. Frese, M. & Zapf, D. Methodological issues in the study of work stress: Objective vs. subjective measurement work stress and the question of longitudinal studies. In C.L. Cooper & R. Payne (Eds), Causes, coping, and consequences of stress at work. Chichester: Wiley, 1988, pp. 375411. George, J.M. Personality, affect, and behavior in groups. Journal of Applied Psychology, 1990, 75, 10716. Hall, P. & Soskice, D. Varieties of capitalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001. Hunter, J.E. & Schmidt, F.L. Methods in meta-analysis: Correcting for bias and error in research ndings. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1990. Jimmieson, N.L. & Terry, D.J. Responses to an in-basket activity: The role of work stress, behavioral control, and informational control. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 1997, 2, 7283. Jones, A.P. & James, L.R. Psychological climate: Dimensions and relationships of individual and aggregated work environment perceptions. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 1979, 23, 20150. Karasek, R.A. & Theorell, T. Healthy work. New York: Basic Books, 1990. Lazarus, R.S. Stress and emotion: A new synthesis. New York: Springer, 1999. Lazarus, R.S. & Folkman, S. Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer, 1984. Mintzberg, H. & Waters, J.A. Of strategies, deliberate and emergent. Strategic Management Journal, 1985, 6, 25772. Morrison, D., Payne, R.L. & Wall, T.D. Is job a viable unit of analysis? A multilevel analysis of demands-control-support models. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 2003, 8, 20919. Muthn, B. & Muthn, L. Mplus users guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthn & Muthn, 1998. Noon, M. & Blyton, P. The realities of work. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1997. Ostroff, C. & Kozlowski, S.W.J. Organizational socialization as a learning process: The role of information acquisition. Personnel Psychology, 1992, 45, 84974. Parker, S.K. Longitudinal effects of lean production on employee outcomes and the mediating role of work characteristics. Journal of Applied Psychology, 2003, 88, 62034. Parker, S.K., Grifn, M.A., Sprigg, C.A. & Wall, T.D. Effect of temporary contracts on perceived work characteristics and job strain: A longitudinal study. Personnel Psychology, 2002, 55, 689719. Parker, S.K., Wall, T.D. & Cordery, J.L. Future work design and practice: Towards an elaborated model of work design. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 2001, 74, 41340. Parkinson, B., Briner, R.B., Reynolds, S. & Totterdell, P. Time frames for mood: Relations between momentary and generalized ratings of affect. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 1995, 21, 3319. Peterson, M.F. Embedded organizational events: The units of process in organizational science. Organization Science, 1998, 9, 1633. Pillow, D.R., Zautra, A.J. & Sandler, I. Major life events and minor stressors: Identifying mediational links in the stress process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1996, 70, 38194. Robinson, M.D. The reactive and prospective functions of mood: Its role in linking daily experiences and cognitive well-being. Cognition and Emotion, 2000, 14, 14576.

Downloaded from http://hum.sagepub.com by Vercellino Daniela on November 5, 2007 2006 The Tavistock Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Daniels Rethinking job characteristics in work stress research

289

Roos, P.A. & Treiman, D.J. DOT scales for the 1970 census classication. In R.A. Miller, D.J. Treiman, P.S. Cain & P.A. Roos (Eds), Work, jobs, and occupations: A critical review of the Dictionary of Occupational Titles. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1980, pp. 33689. Salancik, G.R. & Pfeffer, J. A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Administrative Science Quarterly, 1978, 23, 22453. Sanchez, J.I., Zamora, A. & Viswesvaran, C. Moderators of agreement between incumbent and non-incumbent ratings of job characteristics. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 1997, 70, 20918. Schneider, B.C. The people make the place. Personnel Psychology, 1987, 40, 43753. Scott, W.R. Institutions and organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1995. Semmer, N., Zapf, D. & Grief, S. Shared job strain: A new approach for assessing the validity of job stress measurements. Journal of Occupational & Organizational Psychology, 1996, 69, 293310. Spector, P.E. A consideration of the validity and meaning of self-report measures of job conditions. In C.L. Cooper & I.T. Robertson (Eds), International review and industrial and organizational psychology, vol. 7. Chichester: Wiley, 1992, pp. 12351. Spector, P.E. Using self-report questionnaires in OB research: A comment on the use of a controversial method. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 1994, 15, 38592. Spector, P.E. & Goh, A. The role of emotions in the occupational stress process. Exploring Theoretical Mechanisms and Perspectives, 2001, 1, 195232. Spector, P.E. & Jex, S.M. Relations of job characteristics from multiple data sources with employee affect, absence, turnover intentions, and health. Journal of Applied Psychology, 1991, 76, 4653. Spector, P.E. & OConnell, B.J. The contribution of personality traits, negative affectivity, locus of control, and type A to subsequent reports of job stressors and job strains. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 1994, 67, 112. Spector, P.E., Dwyer, D.J. & Jex, S.M. Relation of job stressors to affective, health, and performance outcomes: A comparison of multiple data sources. Journal of Applied Psychology, 1988, 73, 1119. Spector, P.E., Jex, S.M. & Chen, P.Y. Relations of incumbent affect-related personality traits with incumbent and objective measures of characteristics of jobs. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 1995, 16, 5965. Staw, B.M., Sutton, R.I. & Pelled, L.H. Employee positive emotion and favorable outcomes at the workplace. Organization Science, 1994, 5, 5171. Stone, A.A., Schwartz, J.E., Shiffman, S., Marco, C.A., Hickcox, M. & Paty, J. A comparison of coping assessed by ecological momentary assessment and retrospective recall. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1998, 74, 167080. Suh, E., Diener, E. & Fujita, F. Events and subjective well-being: Only recent events matter. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1996, 70, 1091102. Tennen, H. & Afeck, G. The challenge of capturing daily processes at the interface of social and clinical psychology. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 2002, 21, 61027. Thompson, M., Ellis, R. & Wildavsky, A. Cultural theory. Boulder, CO: Westview, 1990. Vahtera, J., Pentti, J. & Uutela, A. The effect of objective job demands on registered sickness absence spells: Do personal, social and job-related sources act as moderators? Work & Stress, 1996, 10, 286308. Wall, T.D., Kemp, N.J., Jackson, P.R. & Clegg, C.W. Outcomes of autonomous workgroups: A long term eld experiment. Academy of Management Journal, 1986, 29, 280304. Warr, P.B. Work, unemployment and mental health. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987. Weick, K.E. Sensemaking in organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1995.

Downloaded from http://hum.sagepub.com by Vercellino Daniela on November 5, 2007 2006 The Tavistock Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

290

Human Relations 59(3)

Weick, K.E. & Roberts, K.H. Collective mind in organizations: Heedful interrelating on ight decks. Administrative Science Quarterly, 1993, 38, 35781. Weiss, H.M. & Cropanzano, R. Affective events theory: A theoretical discussion of the consequences of affective experiences at work. In B.M. Staw & L.L. Cummings (Eds), Research in organizational behaviour, vol. 18. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, 1996, pp. 174. Weiss, H.M., Nicholas, J.P. & Daus, C.S. An examination of the joint effects of affective experiences and job beliefs on job satisfaction and variations in affective experiences over time. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 1999, 78, 124. Wrzesniewski, A. & Dutton, J. Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of Management Review, 2001, 26, 179201.

Kevin Daniels is Professor of Organizational Psychology, Loughborough University. He has a PhD in Applied Psychology. He is currently an Associate Editor of the Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, and is on the editorial board of the British Journal of Management. His research interests concern the relationships between emotion, cognition and organizational processes. [E-mail: k.j.daniels@lboro.ac.uk]

Downloaded from http://hum.sagepub.com by Vercellino Daniela on November 5, 2007 2006 The Tavistock Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- My Weekly Home Learning Plan For G9Dokument9 SeitenMy Weekly Home Learning Plan For G9Nimfa Separa100% (2)

- Describing Colleagues American English Pre Intermediate GroupDokument2 SeitenDescribing Colleagues American English Pre Intermediate GroupJuliana AlzateNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1994Dokument200 Seiten1994Dallas County R-I SchoolsNoch keine Bewertungen

- PYP and the Transdisciplinary Themes and Skills of the Primary Years ProgramDokument6 SeitenPYP and the Transdisciplinary Themes and Skills of the Primary Years ProgramTere AguirreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Child Labour PPT PresentationDokument20 SeitenChild Labour PPT Presentationsubhamaybiswas73% (41)

- Marketing Plan AssignmentDokument2 SeitenMarketing Plan Assignmentdaveix30% (1)

- BullyrptDokument85 SeitenBullyrptRoxana VornicescuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conflict & NegotiationDokument47 SeitenConflict & NegotiationjoshdanisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Managing Conflict at Work - A Guide For Line ManagersDokument22 SeitenManaging Conflict at Work - A Guide For Line ManagersRoxana VornicescuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Key Expressions in Arab PressDokument6 SeitenKey Expressions in Arab PressFanis LamakoudisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Managing Conflict at Work - A Guide For Line ManagersDokument22 SeitenManaging Conflict at Work - A Guide For Line ManagersRoxana VornicescuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stress ManagementDokument30 SeitenStress ManagementRoxana VornicescuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zoltan Boga ThyDokument4 SeitenZoltan Boga ThyRoxana VornicescuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hardy Personality 09Dokument18 SeitenHardy Personality 09Roxana VornicescuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leo DobesDokument98 SeitenLeo DobesRoxana VornicescuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Umberto ECO - On UglinessDokument457 SeitenUmberto ECO - On Uglinessjanis17100% (4)

- A New Arabic Grammar of The Written LanguageDokument708 SeitenA New Arabic Grammar of The Written LanguageMountainofknowledge100% (6)

- (Journal of Educational Administration) Karen Seashore Louis - Accountability and School Leadership-Emerald Group Publishing Limited (2012)Dokument195 Seiten(Journal of Educational Administration) Karen Seashore Louis - Accountability and School Leadership-Emerald Group Publishing Limited (2012)Jodie Valentino SaingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eapp Summative Test 2023 2024Dokument5 SeitenEapp Summative Test 2023 2024Ed Vincent M. YbañezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment OutlineDokument3 SeitenAssignment OutlineQian Hui LeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grading SystemDokument2 SeitenGrading SystemNikka Irah CamaristaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kindergarten Slumber Party ReportDokument8 SeitenKindergarten Slumber Party ReportFatima Grace EdiloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reflection On Idealism and Realism in EducationDokument2 SeitenReflection On Idealism and Realism in EducationDiana Llera Marcelo100% (1)

- Trigonometric Ratios: Find The Value of Each Trigonometric RatioDokument2 SeitenTrigonometric Ratios: Find The Value of Each Trigonometric RatioRandom EmailNoch keine Bewertungen

- M1-Lesson 1 Part 2 Context Clue Week 2Dokument26 SeitenM1-Lesson 1 Part 2 Context Clue Week 2Jeneros PartosNoch keine Bewertungen

- EAPP LESSON 1 Nature and Characteristics of Academic Text - 033902Dokument3 SeitenEAPP LESSON 1 Nature and Characteristics of Academic Text - 033902Angel PascuaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Characteristics of Informational TextDokument2 SeitenCharacteristics of Informational TextEdwin Trinidad100% (1)

- Hildegard Peplau TheoryDokument28 SeitenHildegard Peplau TheoryAlthea Grace AbellaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Math - Grade 4 Lesson 2b - Using Mental Math To AddDokument3 SeitenMath - Grade 4 Lesson 2b - Using Mental Math To Addapi-296766699100% (1)

- Cooperative Learning Promotes Student SuccessDokument9 SeitenCooperative Learning Promotes Student SuccessKalai SelviNoch keine Bewertungen