Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Freeman ICE Child Porn Case With Improper Search and Seizure Dismissed Oregon

Hochgeladen von

mary eng0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

209 Ansichten24 SeitenThis document is a court order regarding a motion to suppress evidence in a criminal case against Kenneth R. Freeman. The order discusses a hearing held to determine if Freeman consented to a warrantless search of his home by ICE agents on November 29, 2006. The agents seized computers containing child pornography. The court finds Freeman's testimony that he did not consent more credible than the agents' testimony. As there was no warrant, exigent circumstances, or valid consent, the court grants Freeman's motion to suppress the evidence obtained from the illegal search.

Originalbeschreibung:

.

Originaltitel

Freeman ICE Child Porn case with Improper Search and Seizure Dismissed Oregon

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenThis document is a court order regarding a motion to suppress evidence in a criminal case against Kenneth R. Freeman. The order discusses a hearing held to determine if Freeman consented to a warrantless search of his home by ICE agents on November 29, 2006. The agents seized computers containing child pornography. The court finds Freeman's testimony that he did not consent more credible than the agents' testimony. As there was no warrant, exigent circumstances, or valid consent, the court grants Freeman's motion to suppress the evidence obtained from the illegal search.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

209 Ansichten24 SeitenFreeman ICE Child Porn Case With Improper Search and Seizure Dismissed Oregon

Hochgeladen von

mary engThis document is a court order regarding a motion to suppress evidence in a criminal case against Kenneth R. Freeman. The order discusses a hearing held to determine if Freeman consented to a warrantless search of his home by ICE agents on November 29, 2006. The agents seized computers containing child pornography. The court finds Freeman's testimony that he did not consent more credible than the agents' testimony. As there was no warrant, exigent circumstances, or valid consent, the court grants Freeman's motion to suppress the evidence obtained from the illegal search.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 24

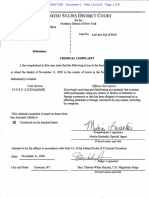

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF OREGON

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff,

v.

KENNETH R. FREEMAN,

Defendant.

Kemp L. Strickland

UNm:D STATES ATTORNEY'S OFFICE

1000 S.W. Third Avenue, Suite 600

Portlard, OR 97204

Of A1tomeys for United States of America

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

No. CR

FINDINGS OF FACT,

CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

AND ORDER TO SHOW CAUSE

Ellen C. Pitcher

OFFICE OF THE FEDERAL PUBLIC DEFENDER

1Ol S.'l1. Main Street, Suite 1700

Portlard, OR 97204

Attonley for Defendant

JONES,

Defendant Kenneth Ray Freeman has been charged in Count One with receipt of child

pornography in violation of 18 U.S.C. 2252(a)(2)(A) and (b)(I), and in Count Two with

possession of c:hild pornography in violation of 18 U.S.C. 2252(a)(5)(B). Currently before the

court are deferildant's Motion to Suppress Evidence and Statements (#14). For the reasons set

forth below, d<:fendant's motion is granted.

DISCUSSION

On June 16,2009, this court held an evidentiary hearing to resolve the issue of whether

Freeman to the warrantless search of his residence, a mobile home located at 1370 E.

Highway 730, Irrigon, Oregon, on November 29, 2006. During the search, three federal agents

from of Homeland Security, Immigration and Customs Enforcement ("ICE")

interviewed Freeman, obtained incriminating statements from him, and seized three computers

from the reside:nce that were later found to contain incriminating images. If the ICE agents'

warrantless emry into Freeman's residence and the ensuing search and seizure violated the Fourth

Amendment, then all evidence acquired as a result of that entry is inadmissible and must be

suppressed. Wong Sun v. United States, 371 U.S. 471,484-86 (1963); United States v.

Shaibu, 920 F.i2d 1423, 1428 (9th Cir. 1990).

The law regarding a warrantless search of a residence is well-established: Whether the

search or seizu:re involves persons or property, "the Fourth Amendment has drawn a firm line at

the entrance to' the house." Payton v. New York, 445 U.S. 573,589-90 (1980). "At the very core

[of the Fourth j:'\mendment] stands the right ofa man to retreat into his own home and be free

from unreasonable governmental intrusion." Silverman v. United States, 365 U.S. 505,

2 - FINDINGS: OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER TO SHOW CAUSE

511 (1961). "..\. warrantless search of a house is per se wueasonable." Payton, 445 U.S. at 586.

"Absent exigency or consent, warrantless entry into the home is impermissible under the Fourth

Amendment." Steagald v. United States, 451 U.S. 204, 211 (1981); Schaiby, 912 F.2d at 1425.

In this case, the government admits that the ICE agents did not have a search warrant, and

that there were- no exceptional circumstances that compelled the agents to enter Freeman's

residence. Ralher, the lead investigator, Senior Special Agent Findley, testified that based on

information he had received from a larger federal investigation into a child pornography

distribution operation in New Jersey, which implicated Freeman as a subscriber to one ofthree

child pornography websites, he and two other ICE agents came to Freeman's property in plain

clothes to conduct an informal "knock and talk" interview on the evening ofNovember 29, 2006.

The government relies entirely on Freeman's consent to establish the legality of the agents' entry

into Freeman's: mobile home, the subsequent search, and the seizure ofthree computers.

1

The

law is well-estiblished that 'Ithe government 'always bears the burden of proof to establish the

existence of effective consent.

ltt

Shaibu, 920 F.2d at 1426 (quoting United States v. hnpink, 728

F.2d 1228, 1222 (9th Cir. 1984 (additional citations omitted).

"Judicial concern to protect the sanctity ofthe home is so elevated that free and voluntary

consent cannot be found by a showing of mere acquiescence to a claim oflawful authority." rd.

10n June 26, 2008, it is undisputed that federal law enforcement agents returned to

Freeman's residence with an arrest warrant that was obtained based on a grand jury indictment

charging him with the receipt and possession of child pornography. After the agents entered the

residence and placed Freeman under arrest, he agreed to speak with the agents, was read Miranda

warnings, s i g n i ~ d a written waiver ofthose rights, and signed a written consent form to permit

agents to searc:l his residence. As a result ofthis search, a computer and other electronic media

used to store inages were seized, and Freeman made inculpatory statements to the arresting

agents.

3 - FINDINGS: OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER TO SHOW CAUSE

(citing Bumper v. North CaroliM, 391 U.S. 543, 548-49 (1968. Therefore, in a case such as

this one, Freeman disputes the consensual nature of the entry and claims that he did not

invite the ICE agents into his mobile home, while all three ICE agents claim that Freeman

"allowed" thera to enter his mobile home after they spoke with him outside for a few minutes, the

government must establish the following:

It must show that there was no duress or coercion, express or implied. The

consent must be "unequivocal and specific" and "freely and intelligently given."

There must be convincing evidence that defendant has waived his rights. There

must clear and positive testimony. '''Courts indulge every reasonable

presum.ption against waiver' of fundamental constitutional rights." Coercion is

implicit in situations where consent is obtained under color ofthe badge, and the

government must show that there was no coercion in fact.

United States v. Page, 302 F.2d 81,83-84 (9th Cir. 1962) (citations and footnotes omitted). "The

government may not show consent to enter from the defendant's failure to object to the entry. To

do so would bt: to justify entry by consent and consent by entry." Shaiby, 920 F.2d at 1427.

Whether a def(mdant's consent is voluntary is determined from the totality of the circumstances,

Schneckloth v. Bustamonte, 412 U.S. 218, 227 (1973), and in this case, the government must

demonstrate that the ICE agents' "knock and talk" practice reflects the defendant's voluntary

consent to the search. See id. at 222.

CREDmILITY ASSESSMENT

In the absence of any contemporaneously written reports by federal law enforcement

agents documenting the events that occurred at the front door of Freeman's mobile home on

November 29,2006, or detailing the means by which the agents obtained Freeman's consent to

enter the residence, conduct a search, and seize Freeman's computers, the court must necessarily

weigh the credi.bility ofthe testimony provided by the three ICE agents who were present for the

4 - FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER TO SHOW CAUSE

"knock and talk," against Freeman's conflicting testimony on the issue of whether Freeman gave

sufficient consent to permit agents to lawfully advance from the front porch of the mobile home,

through the doorway behind Freeman, and into the residence where the search and seizure

ensued. As of the date ofthe suppression hearing, each witness is relying on a recollection of

events that occurred more than two and a half years ago, with very little corroborating evidence

in the record.

For the reasons set forth below, I find Freeman's account of the events that transpired on

November 29, 2006, to be the most credible, and therefore rely on his testimony to resolve any

disputes of fact and to make my fmdings in this case. For Freeman, what occurred that night was

one traumatic event, which he described with detail, clarity, and consistency. In contrast, the

three ICE agents-who each testified that in the course ofhis law enforcement career had

conducted between fifty and one hundred "knock and talk" investigations-lacked detail and

suffered from a number of inconsistencies in several important respects. I fmd that the three

agents' conflicting portrayals of what occurred that night at Freeman's home lack credibility, and

that the methods used to obtain information from Freeman are highly suspect.

First, the ICE agents chose a dark, freezing cold night in an isolated Eastern Oregon

location to conduct their mission. Why didn't they go across the street from their offices to the

United States Courthouse in Portland to obtain a search warrant from a designated U.S.

Magistrate Judge who is on duty twenty-four hours a day? The lead investigator, Agent Findley,

admitted that their mission was not urgent. The agents testified that they had enough basic facts

to link Freeman to a larger federal child pornography investigation, and should have applied for a

5 - FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER TO SHOW CAUSE

search warrant; yet, they chose this dubious "knock and talk" method to gain access to Freeman's

home and seize his computers.

Second, why choose 9:00 p.m. in the dark of night to knock loudly and repeatedly at

Freeman's door to "talk" to him? Absolutely no reason was given to explain why they could not

have visited Freeman's property during daylight hours.

Third, when Freeman admittedly told the agents from inside his residence that he did not

want to talk to them because he was just awakened, was tired, didn't feel well, and offered to talk

to them the next day, why didn't they depart without further discussion? Freeman testified,

unequivocally: "Once before the door opened and twice out there [on the porch], I asked them to

leave; [told them] that I wasn't feeling well; that I needed my sleep and would they please come

back and talk to me when I was in a better condition to talk to them." (Tr. at 119-20.) The

agents should have left and returned at a more reasonable time. No explanation was provided to

justify the agents' continued presence at Freeman's front door.

Fourth, once inside, the agents asked Freeman many incriminating questions, without any

Miranda warnings; although they told Freeman that they were not there to arrest himthat

evening, and portrayed the conversation as a casual, infonnal, question-and-answer session,

Freeman was not actually in a position to freely disengage from the interrogation or to leave the

premises. These agents told Freeman that he was not under arrest even after informing himthat

they had all of his internet "screen names" and had corroborating financial information to use

against him; yet, as he was soon to find out, Freeman certainly was not free to leave or even to

move about in his own home. Freeman testified: "l felt at that point that I was ... going to be

6 - FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAWAND ORDER TO SHOW CAUSE

arrested; that I had no choice in whatever happened after that point. I was scared. I was cold. I

was tired." (Tr. at 121.) When Freeman got up from his recliner chair in the living room, left to

use the restroom for a few minutes, and then went into the mobile home's back bedroom to rest

and put on a shirt and shoes, the agents began yelling at him to come out from behind the closed

door with his hands up. Each agent admitted to pulling out his weapon at this time. When

Freeman opened the door, he sawall three agents out in the hallway, in defensive positions, with

their hands on their weapons. None of three agents' testimony was consistent regarding

Freeman's exit from the living room, or regarding how the events unfolded that led them to

Freeman's back bedroom, where two additional computers were seized. At this point, the "knock

and talk

tl

was clearly a sham.

Fifth, the three ICE agents each gave inconsistent versions ofhow the two computers

from Freeman's back bedroom were obtained. One agent said that Freeman voluntarily retrieved

the computers himself, and just re-appeared in the hallway carrying both computers. Given that

one of the computers was a bulky "tower" style, and the other was a laptop, and given that

Freeman was an overweight fifty-seven year old in poor physical condition, who was suffering

from lower back problems, I find this account to be completely implausible. Another agent

testified that Freeman carried one computer, and an agent carried the other. One agent testified

that he looked into the bedroom and saw Freeman unhooking the tower computer, and another

testified that an agent unhooked that computer. Finally, after changing his story three times, the

agent in charge eventually admitted that he had no personal knowledge about exactly how the

computers were obtained and was just relying on what the other agents had told him. Freeman

testified truthfully that he did not intend to permit the agents to enter his bedroom; they just

7 - FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER TO SHOW CAUSE

walked through the door, saw the tower computer and unhooked it, saw the laptop under the bed

and took it, and at no point did they ever pennit him to touch either computer. Finally, Freeman

testified that the agents escorted him back down the hallway, with the computers in their

possession. I find Freeman's account ofthe incidents that occurred in his back bedroom to be

fully credible.

Sixth, the ICE agents' actions on November 29, 2006, were not then, and never have been

properly reported. There was no report made at or near the time of the event; more than a month

later, the lead agent simply concocted a vague and cursory notation. There was never a notation

in any agent's report recounting the details of any consent Freeman gave at any point-from the

entry into the mobile home, to the seizure of the first computer in Freeman's living room, to the

entry and seizure ofthe two additional computers from Freeman's back bedroom. Further, as

mentioned above, although each agent agreed during the motion to suppress hearing that

weapons were drawn while inside Freeman's home, there was no record made of this significant

event.

Finally, nearly a year and seven months passed before any legal action was taken against

Freeman, when law enforcement agents-including the ICE agents who participated in the "knock

and talk"-arrived to execute an arrest warrant.

From all of the above, I conclude that the three ICE agents' actions were the very anthesis

ofproper law enforcement practices and should not be condoned.

11/

/II

1/1

8 - FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER TO SHOW CAUSE

FINDINGS OF FACT

Based on the record in this case, considering the totality of the circumstances, and having

concluded that defendant Freeman's version of the events is credible, I make the following

findings of fact:

1. On November 29, 2006, when ICE agents Josh Findley, Jim Cole, and Sam Clawer arrived

in an unmarked sport utility vehicle at Kenneth Freeman's mobile home in Irrigon, Oregon,

it was approximately 9:00 p.m., and the temperature outside was roughly 20 degrees

Fahrenheit. The agents were dressed in plain clothing, which included jackets and

sweatshirts appropriate for the weather, when they knocked on Freeman's door.

2. Freeman had returned from a vacation in Mexico the day before, and was asleep in the

bedroom at the rear ofthe mobile home when he was awakened by the agents' insistent

knocking at his door. Freeman was suffering from a number of health conditions, most

notably disc problems in his lower back, for which he had been taking pain medication.

Freeman, who was wearing only his underwear when he was awakened, quickly put on his

pants and socks and came to the front door. Upon learning the ICE agents' identity,

Freeman refused to open the door, telling the agents to go away and come back the next

day because he was tired, didn't feel well, and was not in a condition to talk to them that

night.

9 - FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER TO SHOW CAUSE

3. The ICE agents did not leave the premises, and continued to speak to Freeman through the

closed door. Hoping to convince the agents to leave by speaking with them face-to-face,

Freeman stepped out onto his front porch, closed the door behind him, and spoke with the

agents outside on the porch for approximately five minutes. During the conversation,

Freeman emphatically told the agents that they could not come into his home, that he

wanted them to go away, and that he would talk: to them the next day. He told the agents

he had already gone to bed, he was fatigued, he needed to sleep, and he did not want to

talk to them at that time. While all four men were standing outside on the small front

porch, the agents showed Freeman their law enforcement credentials, explained that

Freeman's name had come up in an investigation of internet websites known to contain

child pornography, and infonned Freeman that they were not there to arrest him but only

to discuss his involvement in the website investigation.

2

Freeman was skeptical and told

them that he did not want to talk about it, but he also did not want to do anything that

would lead to further problems.

4. Agent Findley commented that it was cold and asked Freeman ifhe would rather talk

inside. The agents, who were fully clothed, would not leave Freeman's front porch despite

Freeman's repeated requests for them to go away. Meanwhile, Freeman was standing

outside in the 20-degree weather, clothed only in an underwear T-shirt, a pair of pants, and

2Freeman testified that while he was outside on the front porch there was some general

discussion about a child pornography investigation; however, there was no specific discussion

about the actual evidence the ICE agents had against him. nAil ofthe questions and them telling

me what they had as far as a case against me and everything happened once we got inside the

trailer.

n

(Tr. at 120.)

10 - FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER TO SHOW CAUSE

still in his socks without any shoes. After enduring more than five minutes of persuasion

by the agents, Freeman said, "I'm too cold to stand out here and argue with you. I'm going

inside." (Tr. at 120.) Freeman turned around and opened the door far enough to pennit

him to retreat into the warmth of his residence. His testimony about how the agents

gained entry speaks for itself: "One of the officers reached over my shoulder, opened the

door fully, and basically three men escorted me into my home." Id. I find that none ofthe

ICE agents were expressly or impliedly invited to come into the residence to continue their

mission. I further fmd that Freeman never gave consent, either express or implied, to

pennit the agents to enter his residence.

5. Once inside, Freeman did not ask the ICE agents to leave again, having already asked them

to leave at least three times before, to no avail. Freeman was scared, cold, and tired.

Despite the agents' assurances, Freeman still thought that he would be arrested, and the

agents kept questioning him persistently. Freeman was not at liberty to freely move about

his home. Rather than resist further, Freeman began answering the agents' questions,

made incriminating statements, and eventually acquiesced to the agents' seizure of one

computer from his living room, and two computers from his bedroom.

6. While inside the residence, Agent Findley filled out a "Consent to Search" form dated

11129/06, which Freeman signed, authorizing law enforcement agents to search Freeman's

computers (see Government Exh. 2); Findley also filled out a "Custody Receipt for Seized

Property and Evidence" form dated 11129/06, which Freeman also signed (see Government

11 - FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER TO SHOW CAUSE

Exh. 3). Agent Cole wrote down a few infonnal notes while Freeman was being

interviewed inside the residence, but these notes do not discuss the events that led up to

the agents' entry into the mobile home, or otherwise document the details of Freeman's

discussion with agents outside on the front porch.

7. None of the ICE agents wrote a report or made any entry by dictation or otherwise to

document the events that occurred at the Freeman residence until more than a month later;

the cursory report did not contain a single word as to how the agents obtained consent to

enter and search Freeman's residence. To this day, no ICE agent has written anything in

any report about receiving Freeman's consent to enter; in a report dated March 12,2009,

prepared in anticipation ofthe evidentiary hearing, the author notes only that "Freeman

allowed agents into his residence."

CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

The government has not met its burden to show that Freeman gave "unequivocal and

specific" consent to permit ICE agents to enter his residence on November 29,2006. The

circumstances of this case closely resemble the scenario in Shaibu, where the defendant walked

out of his apartment, left the door open, and during questioning by law enforcement officers, the

defendant turned around and walked back through the door; the officers simply followed without

any clear exchange ofwords seeking and granting permission to enter and search. Shaiby, 920

F.2d at 1424. The Ninth Circuit held as a matter oflawthat such conduct, standing alone, is

insufficient to constitute consent to an entry by law enforcement officers. Id. at 1425.

12 - FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER TO SHOW CAUSE

Not only did Freeman take additional steps to prevent the ICE agents from entering his

mobile home by unequivocally telling them to leave even before he opened the door, but also he

took care to close the door when he stepped outside to respond to the agents' inquiry, where he

again told the agents to leave. After the ICE agents showed their badges, and continued to discuss

Freeman's involvement with a child pornography website while Freeman remained on his front

porch, at night, in sub-freezing weather, clad in barely more than his underwear, the agents

crossed the line from a casual "knock and talk" to set up a situation where Freeman was

compelled to retreat into his residence because they would not leave him alone; he simply opened

his front door, and all three agents-without his permission-followed him inside. Following that

unlawful entry, Freeman submitted to their authority and was coerced into allowing the agents to

remain inside, where they continued to question him, conducted a further search of his residence,

and ultimately seized three computers. "[The] standard in this Circuit [is] that '[c]oercion is

implicit in situations where consent is obtained under color of the badge.'" Id. at 1427 (quoting

Page, 302 F.2d at 84.) The law is unequivocal on this point: "Where there is coercion there

cannot be consent." Bumper v. North Carolini!, 391 U.S. 543, 550 (1968).

Here, as discussed above in the fmdings of fact, there simply was no consent to pennit the

agents to enter Freeman's residence, and thereafter any consent Freeman gave to permit the agents

to search further was certainly coerced. In sum, there was no "clear and positive testimony" that

any of the three ICE agents obtained permission to follow Freeman into his residence, let alone

"convincing evidence" that defendant waived his right to be free from unreasonable searches and

seizures under the Fourth Amendment and thereby "freely and intelligently" consented to the ICE

agents' entry into his residence. See Page, 302 F.2d at 83-84; Shaibu, 920 F.2d at 1426.

13 - FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER TO SHOW CAUSE

I conclude as a matter of law that the ICE agents' initial entry into Freeman's residence

violated the Fourth Amendment. Thus, the remainder of the search and seizure that occurred on

November 29, 2006, was unlawful. The "Consent to Search" form and "Custody Receipt for

Seized Property and Evidence" Freeman signed that night are of no legal effect; "[a]ll evidence

acquired after the entry must ... be suppressed." Shaiby, 920 F.2d at 1428 (citing Wong Sun, 371

U.S. at 484-86; Weeks v. United States, 232 U.S. 383 (1914. Furthermore, all statements

Freeman made to agents while inside his residence on November 29, 2006, and all information

obtained from the computers seized on that date are "fruit of the poisonous tree" and cannot be

used by the government. See Wong Sun, 371 U.S. at 484-86. Finally, because the evidence that

was unlawfully acquired from the November 29, 2006, search and seizure was later used to obtain

the arrest warrant served on Freeman on June 26,2008, all of the evidence acquired subsequent to

the service of that warrant is tainted and must also be suppressed. See id.

DISPOSITION

Defendant's Motion to Suppress Evidence and Statements (#14) is GRANTED IN FULL.

The government conceded at the start of the evidentiary hearing that it would not have sufficient

evidence to proceed to trial ifthe court suppressed the evidence obtained from Freeman both

during the November 29, 2006, encounter and any encounters thereafter. I initially was inclined

to dismiss the indictment in this case based on defendant's motion to summarily dismiss the

indictment on these grounds. (See Motion to Dismiss (#30).) As Justice Cardozo famously said

in reference to the exclusionary doctrine, '''[t]he criminal is to go free because the constable has

blundered.III Maw v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643, 659 (1961), quoting People v. Defore, 150 N.E. 585,

587 (N.Y. 1926. If so, "it is the lawthat sets him free.... [n]othing can destroy a government

14 - FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER TO SHOW CAUSE

more quickly than its failure to observe its own laws, or worse, its disregard ofthe charter of its

own existence." Maw, 367 U.S. at 659.

The government objects to a summary dismissal ofthe indictment in this case, and

requests further review. Accordingly, the government shall have until July 1, 2009, to advise the

court ifany evidence remains to be used in its proceeding against the defendant in light of this

ruling, and to show cause as to why the indictment should not be dismissed. Until the fInal order

of dismissal is entered by this court, Freeman's conditions of pretrial release must remain intact.

IT IS SO ORDERED.

DATED this ,24{~ day ofJune, 2009.

15 - FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER TO SHOW CAUSE

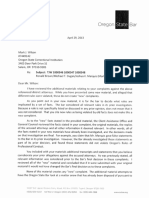

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF OREGON

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, )

)

Plaintiff, ) No. CR 08-289-1-J O

)

v. ) AMENDED ORDER

)

KENNETH R. FREEMAN, )

)

Defendant. )

Kemp L. Strickland

Kelly Zusman

UNITED STATES ATTORNEY'S OFFICE

1000 S.W. Third Avenue, Suite 600

Portland, OR 97204

Of Attorneys for United States of America

Ellen C. Pitcher

OFFICE OF THE FEDERAL PUBLIC DEFENDER

101 S.W. Main Street, Suite 1700

Portland, OR 97204

Attorney for Defendant

1

I granted the government's request for an extension of time to respond to J uly 17,

2009, but the government filed its response by the original date. The defense requested an additional

100 days to respond after the government, but that request is now moot as a result of this disposition.

2

On J une 24, 2008, Freeman was charged with two Counts, receipt of child

pornography in violation of 18 U.S.C. 2252(a)(2)(A) and (b)(1), and possession of child

pornography in violation of 18 U.S.C. 2252(a)(5)(B).

2 - ORDER

J ONES, J udge:

On J une 24, 2009, this court issued Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law ("Findings

and Conclusions") (#35) on defendant Kenneth Ray Freeman's motion to suppress and ordered

the government to show cause by J uly 1, 2009,

1

as to why the indictment against defendant

should not be dismissed.

2

In response to the order to show cause, the government represents that after the

suppression hearing on J une 16, 2009, it found child pornography images on the computer seized

in J une 2008, and raises new legal arguments to challenge my ruling that all of the evidence

acquired as a result of the November 29, 2006, unlawful search and seizure, including the

evidence seized during defendant's arrest on J une 26, 2008, was tainted and therefore suppressed.

Specifically, the government now contends, for the first time in this proceeding, that the

19-month interval between the 2006 unlawful search and seizure and the 2008 arrest and seizure

was so attenuated as to dissipate the "taint" of the original unlawful conduct. For the reasons

explained below, I reject the government's theory, and grant defendant's motion to dismiss the

indictment (#30).

DI SCUSSI ON

As an initial matter, at the outset of the suppression hearing defense counsel

unequivocally stated that the motion to suppress was directed to the evidence acquired both on

3 - ORDER

November 29, 2006, and on J une 26, 2008. She explained to the court that "[a]t that time [J une

26, 2008] there was an arrest warrant, but it was based entirely on the information that was

seized and the evidence that they obtained on November 29, 2006. And if the court suppresses

that evidence, our argument is that everything on J une 26th would also go." (Tr. at 7-8.) The

government then conceded that "[i]f the court suppresses the evidence, the physical evidence that

we have on November 29, 2006, we won't have a case . . . ." (Tr. at 8.) Because I determined at

the hearing that the November 29, 2006, search and seizure was unlawful, I suppressed all of the

evidence and, therefore, initially dismissed the case on the record immediately following the

hearing.

Before I issued my formal Findings and Conclusions, the government objected to

defendant's motion to dismiss the indictment, arguing that dismissal was not an appropriate

remedy. In an attempt to ascertain what was left of the government's case, as part of my

Findings and Conclusions I issued an order for the government to show cause as to why the

indictment should not be dismissed. As mentioned above, despite the prosecutor's concession, in

open court, that a ruling suppressing the 2006 evidence would mean that "[the government]

won't have a case," the government now proposes a theory of attenuation to redeem (or purge the

taint from) the otherwise poisonous fruit, a theory I have considered and find to be untenable

under the circumstances of this case.

According to the government, "[t]o suppress a computer seized during the course of an

otherwise lawful arrest, and pursuant to a valid consent to seize and search form that defendant

readily admits he read and understood, would sweep too broadly." Government's Response, p. 4

(footnote omitted). The government's reasoning apparently rests on the assertion, at page 5 of its

3

"ICE" means Department of Homeland Security, Immigration and Customs

Enforcement.

4 - ORDER

Response, that "this case is somewhat unique in that this defendant was not arrested in

connection with the seizure that this Court has determined was unlawful." If that were so, then

the analysis might be different, but in fact, the arrest warrant executed in J une 2008 was based

entirely on the evidence unlawfully seized in November 2006. Senior Special Agent Findley's

testimony during the suppression hearing underscored this point:

THE COURT: Why did it take you [so many] months [to return to

arrest defendant]?

THE WITNESS: They had problems imaging his

* * *

BY MR. STRICKLAND:

Q Do you know why it took that long?

A Yeah. It was -- there was an issue with the computer forensics on

one of his computers and getting the information off of it. And then there were

other delays, you know. Present the case to the U.S. attorney's office, and, you

know, there's conflicts and stuff like that, so . . .

(Tr. 47-48.) Thus, the government did not develop any independent basis to arrest defendant; the

only reason for the extensive delay between the unlawful search and seizure and the much later

arrest was delay by the government's agents and attorneys themselves.

This court does not accept the government's own delay as a valid underpinning for a

finding of attenuation. Indeed, the Eleventh Circuit recently held that a 21-day delay between

when ICE

3

agents seized a computer hard drive believed to contain child pornography and when

the agents obtained a search warrant to examine the hard drive was so unreasonable as to require

4

In this case, the government delayed approximately one year after the J une 28, 2008,

seizure of the fourth computer before completing the forensic examination of that computer, as

revealed by the government's response. See Government's Response, p. 2 ("When the parties

appeared before this Court for an evidentiary hearing [on J une 16, 2009] on defendant's motion to

suppress, the laptop computer ICE agents seized in J une 2008 . . . had not yet been forensically

analyzed.").

5 - ORDER

suppression of the evidence, particularly because the excuse offered for the delay -- that the

agent "didn't see any urgency of the fact that there needed to be a search warrant during the two

weeks that [he was at a training program]" -- was insufficient. See U.S. v. Mitchell, 565 F.3d

1347, 1351-52 (11th Cir. 2009).

4

In this case, the 19-month delay on which the government

relies for its attenuation argument is attributable solely to the government itself, and the

government has offered little in the way of justification for that delay. Under this circumstance,

to find that the taint from the initial unlawful search and seizure was somehow ameliorated

would lead to an untenable conclusion -- that the taint resulting from an unlawful search and

seizure may be purged merely through the government's own delay in using that tainted evidence

for some period of time. This court cannot and does not accept that theory.

The government relies on U.S. v. Ceccolini, 435 U.S. 268, 279-80 (1978), for the

proposition that "a time lapse of four months is 'substantial,' and favors a finding of attenuation,

particularly for evidence that involves a live witness." Government's Response, p. 4. The

government admits, as it should, that Ceccolini involved evidence in the form of a live witness; a

fair reading of Ceccolini demonstrates that in its reasoning, the Court very carefully

distinguished between physical and testimonial evidence, in significant part because live

witnesses presumably have free will. As the Court explained:

Witnesses are not like guns or documents which remain hidden from view until

one turns over a sofa or opens a filing cabinet. Witnesses can, and often do, come

6 - ORDER

forward and offer evidence entirely of their own volition. And evaluated

properly, the degree of free will necessary to dissipate the taint will very likely be

found more often in the case of live-witness testimony than other kinds of

evidence.

* * *

[O]bviously [the factors we have discussed] all point to the conclusion that the

exclusionary rule should be invoked with much greater reluctance where the

claim is based on a causal relationship between a constitutional violation and the

discovery of a live witness than when a similar claim is advanced to support

suppression of an inanimate object.

Ceccolini, 435 U.S. at 276-77, 280. Thus, Ceccolini, while instructive, does not advance the

government's argument here.

In sum, I find the government's attenuation theory, under the circumstances in this case

and for reasons explained above, to be without merit. Consequently, I only briefly address the

three factors the government promotes as the correct analysis. See Government's Response, p. 3

(citing U.S. v. Washington, 387 F.3d 1060 (9th Cir. 2004)). Under that three-part test, the court

examines the temporal proximity between the illegality and consent; any intervening

circumstances; and the "purpose and flagrancy of the official misconduct." Washington, 387

F.3d at 1073.

With respect to temporal proximity and intervening circumstances, as discussed above, I

find that the government is solely responsible for the delay and that the only "intervening

5

The government contends that an intervening circumstance here is that "this

defendant was not arrested in connection with the seizure that this Court has determined was

unlawful." Government Response, p. 5. As stated earlier in this Order, I reject that proposition and

find, as I did in my Findings and Conclusions (at page 14), that defendant's arrest was based entirely

on the search and seizure that I determined to be unlawful.

7 - ORDER

circumstance"

5

is the government's delay in performing the forensic analysis of the computers

and obtaining the arrest warrant.

With respect to the "purpose and flagrancy of the official misconduct," the government

characterizes the agents' conduct as "at best, negligent conduct." Government's Response, p. 6.

The government takes issue with my description of their conduct, particularly my comment that

"knock and talk" was a "dubious . . . method to gain access to [defendant's] home and seize his

computers." Findings and Conclusions, p. 6. According to the government, "the law in this

Circuit and in this district has been well-settled on the legality and validity of knock and talks for

over 40 years." Government's Response, p. 7. That statement, while accurate in some cases,

disregards that not all "knock and talks" are the same, and not all "knock and talks" have been

upheld in the Ninth Circuit as legal or valid.

In U.S. v. Crapser, 472 F.3d 1141 (9th Cir. 2007), the Ninth Circuit, quoting at length

from U.S. v. Cormier, 220 F.3d 1103 (9th Cir. 2000), indeed observed that:

This Court stated the general rule regarding "knock and talk" encounters almost

forty years ago in the following passage:

"Absent express orders from the person in possession against any

possible trespass, there is no rule of private or public conduct

which makes it illegal per se, or a condemned invasion of the

person's right of privacy, for anyone openly and peaceably, at high

noon, to walk up the steps and knock on the front door of any

man's 'castle' with the honest intent of asking questions of the

occupant thereof - whether the questioner be a pollster, a salesman,

or an officer of the law."

8 - ORDER

That view has now become a firmly-rooted notion in Fourth Amendment

jurisprudence.

Crapser, 472 F.3d at 1146 (quoting Cormier, 220 F.3d at 1109, which in turn quotes Davis v.

United States, 327 F.2d 301, 303 (9th Cir. 1964)).

"Knock and talk" may be a firmly-rooted notion, but the Ninth Circuit has not hesitated

to find that a knock and talk amounts to a seizure instead of a consensual encounter when the

circumstances support such a finding. See Crapser, 472 F.3d at 1146-47, in which the court

explained:

It also is instructive to contrast this case with Orhorhaghe v. INS, 38 F.3d 488

(9th Cir. 1994), in which we found a seizure instead of a consensual encounter.

There, the officers positioned themselves so as to be certain the defendant could

not escape or leave, the officers made a deliberate effort to reveal their concealed

firearms; the encounter occurred in a non-public setting, and the officers acted in

an aggressive manner suggesting that compliance would be compelled. The ratio

of officers to defendants was 4 to 1. Id. at 491; see also United States v.

Washington, 387 F.3d 1060, 1068-69 (9th Cir. 2004)(holding that an encounter

was not consensual where it occurred in a private place, the officers refused to

honor the defendant's request to shut the door, and the officers advised the

defendant several times that he could be arrested and told him he could not

terminate the encounter).

In this case, Agent Findley testified that ICE learned through "various investigations

conducted by our cyber center" that "[defendant] had paid for access to child pornography

websites . . . on 46 different occasions, spanning three years." (Tr. 23.) Through credit card

information and defendant's IP address, ICE tracked defendant's address to Irrigon, Oregon. Id.

According to Agent Findley, the information ICE obtained concerning defendant's payment was

over a year old; Agent Findley did not explain why ICE did not act on the information sooner or

why ICE did not attempt to update its information. Agent Findley did, however, tell the court

9 - ORDER

that he did not apply for a warrant because in this district, the information would be considered

stale. (Tr. 25.)

Despite the lack of recent information sufficient to apply for a warrant, the agents made

an operation plan to go to Irrigon in October 2006. (Tr. 23.) The agents did not conduct the

"knock and talk" at "high noon" in a public place; instead, they conducted it on a cold, dark night

in November 2006 at a private residence in remote Eastern Oregon. The ratio of agents to

defendants was three to one. Further, as I found from the evidence adduced at the suppression

hearing, the agents ignored defendant's multiple requests that they leave; they persisted in their

efforts to get defendant out of his residence; they refused to leave defendant's front porch; and in

essence, pushed their way into defendant's home when he retreated inside. See Findings and

Conclusions, pp. 10-11, 2-4. In view of that evidence, I described the "knock and talk" that

occurred in this case as a "dubious method" to gain access to defendant's home and seize his

computers, a description to which I continue to adhere.

In summary, the government has failed to show cause why the indictment should not be

dismissed. Consequently, I GRANT defendant's motion (#30) and DISMISS the indictment.

IT IS SO ORDERED.

DATED this 13th day of J uly, 2009.

/s/ Robert E. J ones

ROBERT E. J ONES

U.S. District J udge

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- US Vs KnoxDokument32 SeitenUS Vs KnoxJudith Reisman, Ph.D.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Donald Post ComplaintDokument6 SeitenDonald Post ComplaintHouston ChronicleNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4Dokument4 Seiten4api-242831588Noch keine Bewertungen

- Criminal Complaint Against Ryan LoskarnDokument4 SeitenCriminal Complaint Against Ryan LoskarnPhilip BumpNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bryan K. Dickson Child Porn ComplaintDokument11 SeitenBryan K. Dickson Child Porn ComplaintJason TrahanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dearborn Heights Man Charged With Receiving, Distributing Child Pornography in Federal CaseDokument16 SeitenDearborn Heights Man Charged With Receiving, Distributing Child Pornography in Federal CaseCassidyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Michael Morris SentencingMemoDokument34 SeitenMichael Morris SentencingMemoLori Handrahan100% (1)

- R. v. Hammermeister, 2015 ABPC 228Dokument10 SeitenR. v. Hammermeister, 2015 ABPC 228CadetAbuseAwarenessNoch keine Bewertungen

- Circuit JudgesDokument45 SeitenCircuit JudgesScribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jane Does Vs Travis MasseDokument25 SeitenJane Does Vs Travis MasseNickNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jane Doe vs. Miami-Dade County Public School Board - 1501871495226 - 10236595 - Ver1.0Dokument20 SeitenJane Doe vs. Miami-Dade County Public School Board - 1501871495226 - 10236595 - Ver1.0Ben KellerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brooks Anthony - Complaint - Sept 2017 (00000002)Dokument3 SeitenBrooks Anthony - Complaint - Sept 2017 (00000002)WJLA-TVNoch keine Bewertungen

- James Maines Evidence FilingDokument34 SeitenJames Maines Evidence Filingstevennelson10Noch keine Bewertungen

- Strack Search Warrant AffidavitDokument8 SeitenStrack Search Warrant Affidavit48 Hours' CrimesiderNoch keine Bewertungen

- Platt Tech Arrest WarrantDokument5 SeitenPlatt Tech Arrest WarrantHelen Bennett100% (1)

- Criminal Complaint Against Navy SEAL Gregory Seerden Alleging Possession of Child PornographyDokument9 SeitenCriminal Complaint Against Navy SEAL Gregory Seerden Alleging Possession of Child PornographyStefan BecketNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hensley ComplaintDokument6 SeitenHensley ComplaintFOX 17 News0% (1)

- NaderDokument9 SeitenNaderAnonymous 4yLPy0ICNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dr. Teresa Nentwig Gottingen vs. Prof - DR PDFDokument28 SeitenDr. Teresa Nentwig Gottingen vs. Prof - DR PDFTiago CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Provisional RemediesDokument12 SeitenProvisional Remediesrodrigo_iii_3Noch keine Bewertungen

- Buster Hernandez Aka Brian KilDokument38 SeitenBuster Hernandez Aka Brian KilKyle BloydNoch keine Bewertungen

- Federal Prosecutors Filing in Child Porn Case of Democrat OperativeDokument20 SeitenFederal Prosecutors Filing in Child Porn Case of Democrat OperativemicrofailNoch keine Bewertungen

- Caputo ComplaintDokument12 SeitenCaputo ComplaintBreitbartTexasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Doug Saltsman Arrest WarrantDokument6 SeitenDoug Saltsman Arrest WarrantAdam ForgieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Child Porn Indictment of David HuntleyDokument10 SeitenChild Porn Indictment of David HuntleyDetroit Free PressNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jon Frey - Criminal Complaint For Child PornographyDokument10 SeitenJon Frey - Criminal Complaint For Child PornographyVictor FiorilloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Victor Arden Barnard ComplaintDokument38 SeitenVictor Arden Barnard ComplaintDavid LohrNoch keine Bewertungen

- 04133044Dokument31 Seiten04133044aaasdfasdfNoch keine Bewertungen

- Republic of The Philippines Office of The City Prosecutor City of TagaytayDokument4 SeitenRepublic of The Philippines Office of The City Prosecutor City of TagaytayAira CamilleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rosario Complaint (320998)Dokument12 SeitenRosario Complaint (320998)News 8 WROCNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1-17-mj-06401-UA Document 1Dokument14 Seiten1-17-mj-06401-UA Document 1Emma0% (1)

- Cooper Kweme ComplaintDokument9 SeitenCooper Kweme ComplaintEmily BabayNoch keine Bewertungen

- People V BeronillaDokument1 SeitePeople V BeronillaDegardNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kopp - Oberst Indictment Press Release (Final)Dokument2 SeitenKopp - Oberst Indictment Press Release (Final)Nia TowneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Christopher Bour Sentencing MemorandumDokument6 SeitenChristopher Bour Sentencing MemorandumjpuchekNoch keine Bewertungen

- Attorney John Bash Statement On Sentencing of Killeen CoupleDokument2 SeitenAttorney John Bash Statement On Sentencing of Killeen CoupleParisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supreme Court Judgement On Domestic Violence ActDokument56 SeitenSupreme Court Judgement On Domestic Violence ActLatest Laws Team100% (3)

- RitterDokument57 SeitenRitterMikeGoodwinTUNoch keine Bewertungen

- Criminal Complaint: Gregory LisbyDokument11 SeitenCriminal Complaint: Gregory LisbyWWLP-22News100% (1)

- People V MarianoDokument5 SeitenPeople V MarianoChingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Search Warrant For Matthew Stewart's ComputerDokument27 SeitenSearch Warrant For Matthew Stewart's ComputerThe Salt Lake Tribune0% (1)

- People Vs Mancao and AguilarDokument1 SeitePeople Vs Mancao and AguilarKelli WilderNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wolny Federal ComplaintDokument7 SeitenWolny Federal ComplaintAsbury Park Press100% (1)

- Hamilton Police Discipline Decision For Paul ManningDokument60 SeitenHamilton Police Discipline Decision For Paul ManningThe Hamilton SpectatorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Digest On G.R. 166676Dokument2 SeitenCase Digest On G.R. 166676KimJovenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Winona Fletcher AppealDokument80 SeitenWinona Fletcher AppealAlaska's News SourceNoch keine Bewertungen

- THE Court 0F FOR: County, FloridaDokument15 SeitenTHE Court 0F FOR: County, FloridaJanelle TaylorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Forsberg Complaint Document #1Dokument9 SeitenForsberg Complaint Document #1NewsTeam20Noch keine Bewertungen

- Waxman's Email To My Lawyer About Ombudsman ReportDokument1 SeiteWaxman's Email To My Lawyer About Ombudsman ReportLori HandrahanNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. William Irey, 11th Cir. (2010)Dokument256 SeitenUnited States v. William Irey, 11th Cir. (2010)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eduardo Alvarado Charging Information and PCADokument6 SeitenEduardo Alvarado Charging Information and PCAWNDUNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abby - Case Child Abuse - Child PornDokument8 SeitenAbby - Case Child Abuse - Child PornAG DQNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vanderbilt University Anal Gang Rape CocaineDokument16 SeitenVanderbilt University Anal Gang Rape Cocainemary engNoch keine Bewertungen

- US V Matthew Aaron Bondi, ComplaintDokument8 SeitenUS V Matthew Aaron Bondi, ComplaintPINAC NewsNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Manuel Rosario, Marta Serrano, Jose Antonio Vasquez A/K/A "Jose Ramon Vasquez," Hipolito Diaz, A/K/A "Polo," Porfiria Lopez, A/K/A "Giga," Floribell Colon, A/K/A "The Blonde," Jesus Batista-Sanchez, Iris Ortiz, A/K/A "Edie,", 820 F.2d 584, 2d Cir. (1987)Dokument2 SeitenUnited States v. Manuel Rosario, Marta Serrano, Jose Antonio Vasquez A/K/A "Jose Ramon Vasquez," Hipolito Diaz, A/K/A "Polo," Porfiria Lopez, A/K/A "Giga," Floribell Colon, A/K/A "The Blonde," Jesus Batista-Sanchez, Iris Ortiz, A/K/A "Edie,", 820 F.2d 584, 2d Cir. (1987)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coral Lytle 3 29 18Dokument12 SeitenCoral Lytle 3 29 18BayAreaNewsGroupNoch keine Bewertungen

- Randell Adsit Criminal ComplaintDokument8 SeitenRandell Adsit Criminal ComplaintScott AtkinsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kamal Fataliev IndictmentDokument12 SeitenKamal Fataliev IndictmentRyan GraffiusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Childline Child Abuse ReportDokument29 SeitenChildline Child Abuse ReportBren-RNoch keine Bewertungen

- Joseph James Supa ComplaintDokument7 SeitenJoseph James Supa ComplaintWLUCNoch keine Bewertungen

- Father Leo Shea Catholic Priest Affidavit Child Sex Abuse Troy NHDokument18 SeitenFather Leo Shea Catholic Priest Affidavit Child Sex Abuse Troy NHAlan HornNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Peacock, 11th Cir. (2010)Dokument7 SeitenUnited States v. Peacock, 11th Cir. (2010)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Troy Fisher Charging DocsDokument3 SeitenTroy Fisher Charging DocsMatt DriscollNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Serrano, 10th Cir. (2010)Dokument9 SeitenUnited States v. Serrano, 10th Cir. (2010)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wilson Mark J. GC 06-10-10 1000346 Redacted-1Dokument518 SeitenWilson Mark J. GC 06-10-10 1000346 Redacted-1mary engNoch keine Bewertungen

- Binder 2001756 RedactedDokument56 SeitenBinder 2001756 Redactedmary engNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clatsop District Attorney Ron Brown Combined Bar Complaints 12-1-23Dokument333 SeitenClatsop District Attorney Ron Brown Combined Bar Complaints 12-1-23mary engNoch keine Bewertungen

- Disability Rights Oregon Opposed To Expanded Civil Commitment Law SB 187Dokument2 SeitenDisability Rights Oregon Opposed To Expanded Civil Commitment Law SB 187mary engNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cloninger Kasey D DSM CAO 06-26-08 RedactedDokument7 SeitenCloninger Kasey D DSM CAO 06-26-08 Redactedmary engNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leach Larry D. DSM CAO 09-10-18 1801325Dokument6 SeitenLeach Larry D. DSM CAO 09-10-18 1801325mary engNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2023 0203 Original Inquiry BROWN Reyneke Redacted-1Dokument58 Seiten2023 0203 Original Inquiry BROWN Reyneke Redacted-1mary engNoch keine Bewertungen

- Whistleblower Retaliation Clatsop County 23CR23294 Def DocsDokument265 SeitenWhistleblower Retaliation Clatsop County 23CR23294 Def Docsmary engNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pickering Josh A. DSM GC 11-26-18 1801227-1Dokument13 SeitenPickering Josh A. DSM GC 11-26-18 1801227-1mary engNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2022 1003 Original Inquiry BROWN Barbura - 1Dokument15 Seiten2022 1003 Original Inquiry BROWN Barbura - 1mary engNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wilson Mark J. GC 06-10-10 1000346 RedactedDokument518 SeitenWilson Mark J. GC 06-10-10 1000346 Redactedmary engNoch keine Bewertungen

- Noll Iain T. DSM CAO 09-27-16 1601470Dokument5 SeitenNoll Iain T. DSM CAO 09-27-16 1601470mary engNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brown Ronald 1994 0418 Admonition Letter 93-156 27565-1Dokument1 SeiteBrown Ronald 1994 0418 Admonition Letter 93-156 27565-1mary engNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bue Andrew Criminal RecordDokument4 SeitenBue Andrew Criminal Recordmary engNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oregon Defender Crisis 11-2023 McshaneDokument32 SeitenOregon Defender Crisis 11-2023 Mcshanemary engNoch keine Bewertungen

- Project Veritas v. Schmidt Verified Complaint 2020Dokument18 SeitenProject Veritas v. Schmidt Verified Complaint 2020mary engNoch keine Bewertungen

- Project Veritas Action Fund v. Rollins, Martin v. Rollins, No. 19-1586 (1st Cir. 2020)Dokument72 SeitenProject Veritas Action Fund v. Rollins, Martin v. Rollins, No. 19-1586 (1st Cir. 2020)mary engNoch keine Bewertungen

- BOLI Re LIfeboat Beacon Discrimination PDFDokument2 SeitenBOLI Re LIfeboat Beacon Discrimination PDFmary engNoch keine Bewertungen

- Osarch Orak Firearms Arrest - A20154105 - RedactedDokument9 SeitenOsarch Orak Firearms Arrest - A20154105 - Redactedmary engNoch keine Bewertungen

- Veritas v. SchmidtDokument78 SeitenVeritas v. Schmidtmary engNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lifeboat Services Astoria, OregonDokument1 SeiteLifeboat Services Astoria, Oregonmary engNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alan Kessler Oregon State Bar Complaint Review RequestDokument2 SeitenAlan Kessler Oregon State Bar Complaint Review Requestmary engNoch keine Bewertungen

- STEPHEN SINGER, Plaintiff, vs. THE STATE OF OREGON by and Through The PUBLIC DEFENSE SERVICES COMMISSION, Defendant.Dokument35 SeitenSTEPHEN SINGER, Plaintiff, vs. THE STATE OF OREGON by and Through The PUBLIC DEFENSE SERVICES COMMISSION, Defendant.mary engNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mercy Corps Complaint Final 090722 SignedDokument45 SeitenMercy Corps Complaint Final 090722 Signedmary engNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eng, Steve Miscellaneous Papers 96-040Dokument1 SeiteEng, Steve Miscellaneous Papers 96-040mary engNoch keine Bewertungen

- Terry Bean Hush MoneyDokument129 SeitenTerry Bean Hush Moneymary eng100% (1)

- Astoria, Oregon Council Worksession - Expulsion Zones 2-16-2022 v5 HomelessnessDokument21 SeitenAstoria, Oregon Council Worksession - Expulsion Zones 2-16-2022 v5 Homelessnessmary engNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final Misconduct Correspondence From Joshua Stellmon On LiFEBoat Homeless Clatsop Astoria OregonDokument1 SeiteFinal Misconduct Correspondence From Joshua Stellmon On LiFEBoat Homeless Clatsop Astoria Oregonmary engNoch keine Bewertungen

- BudgetDokument132 SeitenBudgetmary engNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scott Herbert Weber - Instant Checkmate ReportDokument47 SeitenScott Herbert Weber - Instant Checkmate Reportmary engNoch keine Bewertungen

- People vs. SevillaDokument3 SeitenPeople vs. SevillajieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Providing Legal Protection For Battered Women - An Analysis of StaDokument391 SeitenProviding Legal Protection For Battered Women - An Analysis of Stavaishali RaviNoch keine Bewertungen

- PDEAFORMDokument2 SeitenPDEAFORMBaguio BushmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- People V MendozaDokument9 SeitenPeople V MendozaJane BandojaNoch keine Bewertungen

- HIGGINS v. WARDEN, MAINE STATE PRISON - Document No. 4Dokument2 SeitenHIGGINS v. WARDEN, MAINE STATE PRISON - Document No. 4Justia.comNoch keine Bewertungen

- Narcotics Control Bureau Vs Kishan Lal and Ors 2901203s910347COM244515Dokument8 SeitenNarcotics Control Bureau Vs Kishan Lal and Ors 2901203s910347COM244515Geetansh AgarwalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lobster59 - Review - A Terrible Mistake - Anthony FrewinDokument13 SeitenLobster59 - Review - A Terrible Mistake - Anthony Frewinchaulo75Noch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Eric Bennett, 4th Cir. (2012)Dokument14 SeitenUnited States v. Eric Bennett, 4th Cir. (2012)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bernstein of Leigh V Skyview & GeneralDokument17 SeitenBernstein of Leigh V Skyview & Generalzaimankb100% (1)

- A.C. No. 10537Dokument7 SeitenA.C. No. 10537Maria Celiña PerezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Suleiman Said Shahbal V Independent Electoral and Boundaries & 3 OthersDokument6 SeitenSuleiman Said Shahbal V Independent Electoral and Boundaries & 3 OthersBen MusimaneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Limbo Vs People 2023Dokument28 SeitenLimbo Vs People 2023Anthony Isidro Bayawa IVNoch keine Bewertungen

- US Kun Shan Chun Sealed ComplaintDokument15 SeitenUS Kun Shan Chun Sealed ComplaintSyndicated NewsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 21 Manuel Lim Vs CA G.R. No. 107898Dokument5 Seiten21 Manuel Lim Vs CA G.R. No. 107898SDN HelplineNoch keine Bewertungen

- Webb v. PPDokument2 SeitenWebb v. PPArjay Volante SantiagoNoch keine Bewertungen

- R14 Victory Liner v. Bellosillo, 425 SCRA 79 (2004)Dokument15 SeitenR14 Victory Liner v. Bellosillo, 425 SCRA 79 (2004)Airess Canoy CasimeroNoch keine Bewertungen

- En Banc A.C. No. 8494, October 05, 2016 Spouses Emilio and Alicia JACINTO, Complainants, v. ATTY. EMELIE P. BANGOT, JR., Respondent. Decision Bersamin, J.Dokument7 SeitenEn Banc A.C. No. 8494, October 05, 2016 Spouses Emilio and Alicia JACINTO, Complainants, v. ATTY. EMELIE P. BANGOT, JR., Respondent. Decision Bersamin, J.wedwdwdNoch keine Bewertungen

- Law AssignmentDokument11 SeitenLaw AssignmentZaima LizaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lab RevDokument98 SeitenLab RevDeus DulayNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Samuel Brantley, A/K/A "Pee Wee", Clifford Washington, Richard David Blackston, Alfred R. Canas, A/K/A "Sonny", James Murray, Carroll Barrett Zeigler, 733 F.2d 1429, 11th Cir. (1984)Dokument20 SeitenUnited States v. Samuel Brantley, A/K/A "Pee Wee", Clifford Washington, Richard David Blackston, Alfred R. Canas, A/K/A "Sonny", James Murray, Carroll Barrett Zeigler, 733 F.2d 1429, 11th Cir. (1984)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Benchbook TablesDokument18 SeitenBenchbook TablesHelen Grace M. BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Nicholson, 4th Cir. (2007)Dokument16 SeitenUnited States v. Nicholson, 4th Cir. (2007)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen