Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Multilateralism, Multipolarity, and Beyond A Menu of Russia's Policy Strategies (Makarychev and Morozov)

Hochgeladen von

Александр БовдуновOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Multilateralism, Multipolarity, and Beyond A Menu of Russia's Policy Strategies (Makarychev and Morozov)

Hochgeladen von

Александр БовдуновCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Global Governance 17 (2011), 353373

Multilateralism, Multipolarity, and Beyond: A Menu of Russias Policy Strategies

Andrey Makarychev and Viatcheslav Morozov

The article examines the main approaches to multilateralism that coexist in Russian foreign policy thinking. It argues that these approaches must be put in the context of the debate on multipolarity, which comes out as a direct opposition to the Western collective unilateralism. Both as an abstract model and as a concrete practice, multipolarity is not synonymous with multilateralism; certain visions of a multipolar world, such as greatpower management, are hardly compatible with multilateralism if the latter is grounded in the idea of equality of all participants in the international system. It is also crucial to take into account the origins of the Russian doctrine of multipolarity in the particular context of Russias uneasy relationship with the West. Against this background, it is clear that some traditional foreign policy strategies, such as balance of power, can result in both unilateralist and multilateralist outcomes. The articles main conclusion is that the contradictory dynamics of identity and security, in Russia and in the West, seem to produce a trend in favor of great-power management as the model of future international order. If this is true, it means that there is a move toward a type of international society where egalitarian multilateralism is replaced by a more hierarchical structure. KEYWORDS: Russia, multipolarity, multilateralism, great-power management, balance of power.

AFTER THE TERRORIST ATTACKS AGAINST THE UNITED STATES IN 2001, THEN secretary of state Colin Powell famously declared the end of the postCold War era. Although this announcement has been contested repeatedly, and many alternative dates have been proposed, September 11 definitely was a major turning point in the development of the international system that was symbolically located almost exactly at the turn of the century. For Russia, however, the twenty-first century began at least two years earlier, ushered in by NATOs Operation Allied Force against Yugoslavia launched in March 1999 and the start of the second Chechen campaign in the fall of the same year. These events concurredand not accidentallywith the dawn of Vladimir Putins epoch, thus laying the foundation for Russia as it is today. By the dramatic moment of President Boris Yeltsins resignation on New Years Eve 2000, the worldview that was to shape Russian foreign policy and domestic politics in the years to come had already consolidated and become common sense for a large majority of the Russians.

353

354

Multilateralism, Multipolarity, and Beyond

Throughout the 1990s, the new Russian democratic state considered participation in, and cooperation with, Western-dominated multilateral institutions to be largely within its long-term interest. In terms of practical foreign policy steps, the pro-Western attitudes peaked in 1990 when the Soviet Union agreed to the German reunification and supported the US-led coalition in the Gulf War. This, however, was a sign of Russias weakness at least to the same extent as of genuine belief in the shared interests with the West. As Yeltsins government consolidated in the aftermath of the Soviet collapse, its reaction to the Western policies typically ranged between grudging acceptance and growling resentment. However, it was during that decade that Russia was accepted to the Council of Europe (1996) and to the Group of 8 (G8; 1997) and signed its first comprehensive agreements with the European Union (EU; 1994) and NATO (1997). It inherited its permanent seat at the UN Security Council from the USSR, but used its veto power sparingly. Even if increasingly unhappy with the state of the relationship, Moscow saw no real alternative to integration into the transatlantic multilateral institutions. The disappointment accumulated over a number of issues such as the situation in the Balkans, the state of affairs in the post-Soviet space, or the criticism of Russias actions in Chechnya during the first campaign (launched in 1994). Yet it was the war in Kosovo that actually changed the balance: seen by most Russians, experts, and ordinary people alike as a cynical abuse of human rights rhetoric for the sake of geopolitical expansion,1 it destroyed what was left of trust in Western policies and institutions and, together with rising oil prices, paved the way toward the more assertive and independent foreign policy. This change involved a reassessment of what Alexei Bogaturov dubs a bloodless coup in international relations,2 which supposedly occurred in the mid-1990s. What the West baptized a new international community turned outin Russian eyesto be a club-like consolidation of well developed democracies that claimed to incarnate an allegedly indisputable perspective for the entire mankind.3 In the minds of many Russian analysts and policymakers, the NATO intervention in the Balkans is a perfect example of the imposition of Western rules on the neighboring territories. Yet they argue that, apart from this type of collective unipolarity, there is an alternative model of international society based on the new subjectivities that non-Western countries are eager to acquire. Bogaturov describes this model as a conglomerate of enclaves, interacting, but not doomed to mutual assimilation,4 but it is perhaps better known as the idea of a multipolar world. At first glance, the world order envisaged by the doctrine of multipolarity can be favorable to multilateral diplomacy: indeed, as we demonstrate below, multilateralism can be interpreted as one of the possible forms that multipolarity might take. However, it is crucial to take into account the origins of the Russian doctrine of multipolarity in a particular historical context. Being to a large extent a reaction against Western collective unilateralism, it is more

Andrey Makarychev & Viatcheslav Morozov

355

often used to legitimize unilateral policies that are designed as countermeasures to the alleged interventionism of the West. In addition to that, it produces regional and global multilateral solutions that are also seen as balancing exercises aimed at the creation of the alternative centers of power. At the same time, Russian foreign policy can hardly be described as resolutely anti-Western: Moscow continues to ally with the EU and the United States in a number of bilateral and multilateral contexts. Thus, the attitude toward multilateralism in Russian foreign policy thinking and practice is multifaceted and does not follow a certain straightforward definition of the national interest. It is not only, and even not mainly, the case of the difference between the areas that Russia seeks to control and those that it does not.5 Rather, it depends on the complex identity dynamics between Russia and the West as well as on the interplay between multipolarity and multilateralism as conceptual tools. In what follows, we consider the main approaches to multilateralism that coexist in Russian foreign policy thinking. We believe that, in order to be properly understood, these approaches must be placed in the context of the debate of multipolarity, which is the primary value-laden notion put in direct opposition to the Western collective unilateralism. Multipolarity is not synonymous with multilateralism; certain visions of a multipolar world, such as greatpower management (GPM), are hardly compatible with multilateralism if the latter is understood as premised on the idea of equality of all participants in the international system.6 In the next section, we map out the approaches to multipolarity that are present in the Russian debate. The subsequent sections explore these approaches, focusing first of all on the analysis of the multipolar solutions that they produce or promote. Our main conclusion is that the contradictory dynamics of identity and security concerns both in Russia and in the West seem to produce a trend in favor of GPM as the model of a future international order. If this is true, it means that we are moving toward a type of international society where egalitarian multilateralism is replaced by a more hierarchical structure.

Multipolarity Unpacked The idea of multipolarity established itself as an image of the ideal future world order and as a practical policy goal during the time that Evgeny Primakov served first as minister for foreign affairs (19961998) and later as prime minister (19981999). It gained political legitimacy after the Kosovo campaign and was financially backed by huge resources with the improvement of Russias economic situation during Putins presidency, with Russia now being able to invest more in the consolidation of the alternative poles. The Foreign Policy Doctrine, signed by the president in June 2000, states that Russia shall seek to achieve a multi-polar system of international relations that really reflects the diversity of the modem [sic] world with its great variety of interest,7 thus estab-

356

Multilateralism, Multipolarity, and Beyond

lishing multipolarity as one of the key policy goals. The most vocal declaration of the principle of multipolarity as directed against the West is perhaps the famous speech by Putin at the Munich Conference on Security Policy in February 2007, where he describes the unipolar world promoted by the West as a world of one master, one sovereign. He argues that unilateral, illegitimate actions of the United States and its allies are detrimental to global security because they produce new conflicts and wars, intensify the nuclear arms race, and lead to a situation where no-one feels secure. Because no-one can find refuge behind the stronghold of the international law.8 The arrival of the new administration in 2008 changed the tone of the debate and the position of multipolarity on the foreign policy agenda. Dmitry Medvedev claims that the imperfections of a unipolar order can be explained by its potentially divisive nature ending up with the bloc-based approaches,9 or the formation of alternative groups of allied states to resist the domination of the core power(s)a situation that might be labeled contested unipolarity.10 However, the new Foreign Policy Doctrine of July 2008 describes multipolarity as an emerging phenomenon,11 thus placing it in the immediate future and even perhaps in the present. The dramatic events of the following month shifted the time horizon even further when Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov stated that the unipolar world ceased to exist as a result of Russias military victory over Georgia.12 Russia thus claims to base its policy on the fact that the material basis of the Western supremacy in global politics has been shaken, and even though the right-wing conservative forces in the United States are trying to go back to the confrontational policies of the previous administration, in the long run these attempts are futile because they run counter to the most fundamental trends in global politics and economics.13 Echoing the official discourse, most Russian policymakers and opinion makers postulate that multipolarity, being initially conceived as an academic concept, has gradually transformed into objective geopolitical reality, a fact of the being, if not an axiom that needs neither proofs nor further problematization.14 At the same time, one cannot say that the Russian official position can be reduced to a straightforward dismissal of Western multilateralism as collective unilateralism. As evidenced by the discourse of modernization as well as by a number of concrete foreign policy steps, Moscow does accept Western leadership in the normative field, although this acceptance is mostly tacit and never unproblematic. There is a passage in the 2008 Foreign Policy Doctrine that is symptomatic of Russias predicament: while it criticizes the historic West for clinging to its monopoly in global processes, it nevertheless insists that the future intercivilizational competition between different value systems and development models is going to take place within the framework of universal democratic and market economy principles.15 What this wording illustrates is that Russia, even when it opposes the West, cannot present a

Andrey Makarychev & Viatcheslav Morozov

357

meaningful alternative and, thus, has to use the language of liberal democracy to voice its concerns. It is not a coincidence that sovereign democracy came up as the key slogan summing up the essence of Putins presidency.16 The complexity of the Russian discourse on multipolarity invites a watchful scrutiny of the concept as such. A synthesis of the literature on Russias views of the future of the world order, some of which is discussed below, yields a menu of at least seven policy strategies that are shown in Table 1. It is formed on the basis of two kinds of distinctionsbetween interest-based and normative strategies, and between state-centric strategies and those reaching beyond the state and involving a wider gamut of participants. The first dichotomy is conceptually grounded in Arnold Wolferss idea of milieu goals, as opposed to possession goals. Milieu goals are those which, while indirectly related to a particular actors specific interests, are essentially concerned with the wider environment within which international relations unfold.17 Thus, normative policy strategy aims to shape the institutional milieu by regulating it through international regimes, organizations, and law. The second dichotomy is predicated on the distinction between an international system dominated by sovereign states, and a transnational community of postsovereign/post-Westphalian actors with stronger cosmopolitan perspectives. It is within the four resulting blocks that different policy strategies can be located. The identification of these strategies does not necessarily imply a search for certain groups that allegedly may stay behind each of them. This is a typology of scenarios sustained by different articulations of Russias role identities, yet neither of them belongs to any specific political group. Neither of them has its bearers; the same group may simultaneously adhere to two or more strategies, thus demonstrating the high volatility of Russias role identities. All of these strategies, despite the specificity of each, share at least two traits in common. First, they are explicitly anti-imperial in a sense that they challenge a world order model based on a new edition or revival of the imperial forms of subjectivity. The idea of unity, it can be argued, has discredited itself in Russia due to its proclivity to take imperial form(s). Second, they are about managing diversity as the constitutive institutional characteristic of international society. If one rejects the idea of the unipolar world as imperialist,

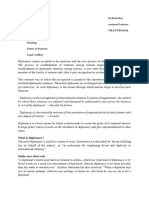

Table 1 Russias Choice of Strategies Toward Multipolarity Interest-based Strategies State-centric strategies Balance of power Great-power management (Transatlantic) multilateralism Polycentrism Multiregionality Normative Strategies Promotion of international democracy

State plus strategies

Dialogue of civilizations

358

Multilateralism, Multipolarity, and Beyond

this leaves open the question of how to keep in check anarchy which, according to the classical view, presents itself as an inherent feature of international society.18 Multilateral institutions come out as only one way of dealing with this task. Moreover, multilateralism can be present as a possible tool in many of the other scenarios described here. Multilateral solutions that in effect are nothing but instruments to advance other strategies can still be presented as important in their own right because the prevailing normative order favors multilateralism over coercion and other similar means of imposing order. In the following analysis of the role played by multilateralism in Russian foreign policy, we explore various strategies to the extent that they rely on multilateral frameworks and try to explicate the roles played by the latter in each particular strategy. We start with the most obvious understanding of multilateralism as participation in the multilateral frameworks centered on the transatlantic community. We then look at how multilateral solutions are built into the paradigm of balance of power, which traditionally dominates Russian foreign policy thinking. The recent developments, however, might point in the direction of a more cooperative system that is described by Hedley Bull as great-power management. Finally, we briefly discuss the remaining alternative approaches that are all to some extent present in the Russian debate, but do not have any profound significance for the practice of foreign policy.

Transatlantic Multilateralism or Collective Unilateralism? Multilateralism, taken abstractly, views multipolarity through formalized and inclusive institutionalist lenses, presupposing coalitions of different formats among sovereign states. Traditionally, it was in the West that multilateralism gained its popularity as the most desirable model of multipolarity.19 And the conventional use of the concept usually implies multilateral frameworks where the transatlantic community plays the leading role such as NATO or the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). To differentiate this from the other types of multilateralism that we discuss below, we use the term transatlantic multilateralism to refer to this conventional meaning. The Russian record of cooperation with the multilateral institutions in the transatlantic area is uneven at best. As mentioned above, it was in the 1990s that Russia succeeded in entering major international bodies (the G8 and Council of Europe) and establishing formal cooperation with others (NATO and the European Union). It was also quite active in the OSCE framework, inter alia, lobbying for the adoption of the European Security Charter. However, by the time that the charter was ready for signature at the Istanbul summit in November 1999, Russias standing within both the OSCE and the Council of Europe was severely undermined by the hostilities in Chechnya and it has never fully recovered.20 A brief period of improvement after the September 11 attacks, which resulted in the Rome agreements of May 2002 and

Andrey Makarychev & Viatcheslav Morozov

359

the establishment of the NATO-Russia Council, was soon brought to an end by the intervention in Iraq, the color revolutions in the post-Soviet space, and the George W. Bush administrations policy on missile defense.21 The evolution of the Russian political system since 2000 and the establishment of the vertical of power damaged relations even further because it led to ever harsher criticism of Russias democratic record. European institutions have never stopped expressing their concerns over the situation in Russia, and Moscow often pays back by putting a spoke in the wheel. In recent years, it has threatened to reduce its financial contribution to the OSCEs budget; drastically limited the number of OSCE election monitors at the 2007 2008 federal elections; unilaterally suspended the Conventional Forces in Europe Treaty; procrastinated with the ratification of Protocol 14 to the European Convention on Human Rights, thus delaying the implementation of the reform of the European Court; and was unable to conclude a new treaty with the EU after the 1994 Partnership and Cooperation Agreement expired in December 2007. The only multilateral framework against which Russia seems to have no major reservation is the nuclear nonproliferation regime, although its cooperation with the West in this context has been marred by constant disputes over the Iranian nuclear program.22 The Russian-Georgian war of August 2008 clearly demonstrated Moscows strong preference for bilateral deals over multilateral frameworks. Georgias desire to join the transatlantic multilateral institutions, first of all NATO, was in itself one of the key contributing factors to the escalation of the conflict (although by no means the only one). Yet even more characteristic were the diplomatic developments after the war broke out. The mediation of French president Nicolas Sarkozy was absolutely decisive for the cease-fire agreement and, as many analysts point out, it was fortunate that it was France, a country that Moscow considers one of its key partners within the EU, which happened to hold the rotating EU presidency in the second half of 2008. On the contrary, the multilateral frameworks that had tried to contain the conflicts in Abkhazia and South Ossetia since the early 1990s were ignored and even partly destroyed by Russia after the war. Thus, Moscow vetoed the prolongation of the OSCE missions mandate in Georgia, demanding that it be renamed to acknowledge the sovereign status of the two breakaway regions.23 Russia at least could exert some influence in the West-centered multilateral political and security frameworks, even if often it was a type not seen as constructive by the West. In the economy-oriented institutions of the neoliberal global society, Russias record has been even poorer. Its membership in the G8 remains incomplete because it does not take part in regular meetings of finance ministers (which, thus, remains the group of seven).24 The most illustrative, however, is perhaps the story of Russias still unfinished accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO). It applied for membership as far back as 1993, and the talks have dragged on without any vigor since 1995. The

360

Multilateralism, Multipolarity, and Beyond

Putin administration took this matter seriously and managed to achieve significant progress by 2006, when the bilateral talks were largely completed. However, for the past five years, the estimated time of Russias entry has been defined by phrases like before the end of next year. Although the complications that have remained since 2006 are largely bilateral in nature and concern trade issues with the EU and the United States, as well as more politicized disputes with countries like Georgia and Moldova, this situation is indicative of how difficult it is for Russian diplomacy to operate in complex multilateral settings. Characteristically, the most recent complication on the way toward WTO entry arose when, in June 2009, Prime Minister Putin suddenly declared that Russia would join as a member of a Customs Union that also includes Belarus and Kazakhstan. This effectively postpones membership almost indefinitely since Kazakhstans progress toward the WTO has been much slower than Russias and, at best, Belarus is at the beginning of this road. Even though this declaration was revoked (after several months of hesitation), it indicated that, at least for a part of the Russian political elites, multilateral solutions in the space of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) have priority over the transatlantic frameworks.25 President Medvedevs proposal on the new security architecture in Europe, first formulated in his speech in Berlin in June 2008,26 is also conceptually grounded in the idea of multilateralism. However, the draft European Security Treaty, which was supposed to give legal certainty to this proposal,27 was negotiated with other great powers, primarily on a bilateral basis. The Western responses to Medvedev contain much more explicit references to the desirability of multilateralist agenda, which is strategically appealing to the EU in particular.28 Yet multilateralism can certainly be part of Russias relationship with the EU in a different respect. A think tank close to President Medvedev argues that Russia has to accept the prospects of the EU-CIS and China-CIS multilateral relationship,29 which enables Moscow to give up ambitions of monopolizing the post-Soviet region. In developing its multilateral strategy, Moscow certainly has to react to such proposals by European experts as, for example, the idea of a European security trialogue to include the EU, Turkey, and Russia.30 To sum up, the goal of integrating into the Western-dominated multilateral structures is significantly discredited in Russia by the lack of practical results, which is exacerbated by the ideological aversion to the even partial delegation of sovereignty that thick multilateral commitments entail. Nevertheless, Russia does recognize the validity of multivector networking diplomacy and seems to increasingly rebuff the logic of unilateral actions as ineffective and futile. In fact, the suspicions against transatlantic multilateralism are, to a large extent, motivated by the fact that Russia does not see this type of solution as truly multilateral. This position solidified during the Kosovo conflict, when Moscow first refused to authorize the use of force by a UN Security Council

Andrey Makarychev & Viatcheslav Morozov

361

resolution, and then condemned NATOs action as unilateral and in violation of the UN Charter. According to Moscow, Security Council Resolution 1244, which was claimed by the NATO allies as the legal basis for Operation Allied Force, did not authorize the use of military means against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.31 The differentiation between true multilateralism and collective unilateralism was also behind Russias position on the US-led interventions in Afghanistan in 2002 (which later came under the auspices of NATO) and Iraq in 2003. The intervention in Iraq was vehemently condemned from the outset: Russia, this time supported by France, Germany, and (less vocally) China, blocked the US attempt to obtain Security Council authorization for the operation and did not spare the harshest words to condemn it as a violation of international law. Moscows position on the Afghan case was, on the contrary, positively neutral in the beginning and has since evolved into a pragmatic partnership, especially after the Barack Obama administration managed to sign agreements with Russia on the Afghan military transit.32 A similar trend can be observed in the case of Moscows position on Iran. In this case, however, it started from a lower ground: under George W. Bush and Putin, there was obvious and open disagreement on the Iranian nuclear problem. Obama and Medvedev managed to find at least some common ground on the issue. In the end, this got as far as Russias support of Security Council Resolution 1929 imposing tougher sanctions on Iran in June 2010 and its abandonment of plans to supply Tehran with the S-300 air defense installations in September of that year. It is almost certain, however, that the latter moves necessitated quite a bit of bilateral horse-trading with Washington, which involved the US plans for missile defense. This indicates that the recent progress in cooperation with NATO and the United States can perhaps be better described not as Russia finally linking up with the transatlantic multilateral frameworks, but as relatively successful instances of GPM. Before moving on to this model, however, we consider the approach that has deeper roots in the Russian foreign policy tradition and, thus, a crucial influence on the understanding of multilateralism.

Balancing the West In the Russian perspective, balance of power sometimes looks as the only, or at least the most adequate, model of the multipolar world. It prioritizes sovereign independence of states on the international arena, and the way that this concept is legitimized often is reminiscent of Carl Schmitts advocacy of pluralism in world politics.33 Most important, however, the Kremlin-promoted multi-polar world is a direct and unequivocal alternative to globalization.34 Consequently, this vision is based on the opposition to unilateralism (especially the collective unilateralism of the West) and is grounded in the logic of sovereign decisions that Russia itself favors and expects from other countries

362

Multilateralism, Multipolarity, and Beyond

as well. This can be illustrated by President Medvedevs repeated suggestions that the Western countries need to be pragmatic and guided by their own genuine interests35 as well as by multiple statements by other members of the political elites to the effect that, within the multipolar society, each country is supposed to represent its own interests, instead of delegating its functions to EU, NATO and other international organizations.36 This seemingly antiinstitutional and antinormative utterance is a blunt declaration of Russias mistrust of those forms of international cooperation that entail a dispersal of sovereignty understood by Moscow as a right to control territories rather than as a responsibility to population. It must be emphasized, however, that the dominance of balance of power as the foreign policy ideology has never been absolute. The normative appeal of multilateralism is strong enough to make an impact even on the policies whose starting point is the perceived need to balance the excessive influence of the West; in particular, in the post-Soviet space. The creation of the Commonwealth of Independent States in 1991 would not be a good illustration here because it was initially conceived of as a form of a civilized divorce aimed at mitigating the consequences of the dissolution of the USSR. The same is probably valid for the initial impulse for the Collective Security Treaty, initially signed by six CIS member states in Tashkent in May 1992, with three more partners joining in 1993. However, the subsequent development of international institutions in the CIS space can be described as strategic use of Russias influence as the former imperial center with a view toward creating a counterbalance to the West. The loose structure of the CIS was supplemented with a Customs Union of six member states in 1993, which was converted into the Eurasian Economic Community (EurAsEC) in 2001. Even though the latter structure remained largely dysfunctional, its institutions were symbolically modeled after those of the European Economic Community. Moscows attempts to initiate real economic integration in the post-Soviet space finally bore fruit with the launch in 2010 of the Customs Union of Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Russia.37 The three countries managed to agree on a common customs tariff and even declared their aim to set up a Common Economic Space (again, modeled on the European Economic Area) as of 2012.38 The progress in the field of military and security integration has been equally impressive. The fact that Russian peacekeepers were stationed in Abkhazia and South Ossetia under a CIS mandate gave Moscow a legitimate way of supporting the loyal regimes in these self-proclaimed states. The multilaterally confirmed status of the Russian troops was crucial for the international assessment of the August 2008 war since it was difficult to overlook the fact that the military operation launched by Tbilisi involved an attack on the formally neutral peacekeeping force. The Tashkent Treaty provided the base for the establishment in 2002 of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), which has since moved beyond purely symbolic integration by, inter

Andrey Makarychev & Viatcheslav Morozov

363

alia, holding regular military exercises and even setting up its own Rapid Reaction Force in 2009. The importance of the CSTO was highlighted during the riots in Kyrgyzstan in June 2010, when Russia was called on by some of its CSTO partners and NATO member states to intervene and put an end to the hostilities. Had Moscow chosen to do so, it would have created a precedent as being the first major peace enforcement operation conducted by Russia in the post-Soviet space and legitimized by a multilateral institution. Whatever the reasons for the Kremlins decision to the contrary, the existence of a strong institutional framework for balance of power multilateralism must not be overlooked. Last but not least, the creation of the Shanghai Five in 1996, to be transformed into Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) of six member states in 2001, brought in another powerful player (China), thus potentially transforming the rules of the game. However, the evolution of the SCO probably illustrates a different trend in Russias use of multilateralism. Since the late 1990s and throughout the previous decade, cooperation with China was seen mainly in balancing terms, perhaps also as part of the future Russia-ChinaIndia triangle, which was put on the foreign policy agenda by Evgeny Primakov, and still figures prominently in the 2008 Foreign Policy Doctrine. The question of how far Russia would go in its balancing policies started to sound alarming when, in 20072008, Irans full membership was seriously discussed in some quarters. However, this scenario never materialized. What is more, in June 2010 the SCO adopted formal membership rules stipulating that no country subject to the UN sanctions can join the organization. Overall, there seems to be a growing concern over what is perceived as Chinas excessive influence in Central Asia. The current Russian position on the SCO is to describe it as a useful framework to handle the regional security issues, but to view it as complementary, rather than competing, to the expanding cooperation with the United States and NATO on Afghanistan and a wider set of security concerns in South and Central Asia. The initial euphoria after the victorious operation against Georgia in August 2008 strengthened the appeal of the balance-of-power approach. Russia not only demonstrated serious determination to apply military force in its near abroad, but also openly announced its zones of special interest.39 What was left unnoticed for a while was the fact that the idea of balancing suggests a certain degree of conflictuality between different poles that might be inimical tobut are supposed to containeach other. In other words, balance of power presupposes divides and clashes between a number of poles that might be stronger than Russia. Those Russians who are eager to achieve multipolarity should be ready to face the new rising centers of power, a Russian author convincingly claims and then continues: There are absolutely no guarantees that in a world with unbalanced power centers Russia would be able to successfully pursue a policy of balanced equidistance.40 Arguably, the imple-

364

Multilateralism, Multipolarity, and Beyond

mentation of this version of multipolarity may be conducive to further destabilization in the Middle East, strengthening of Iran, military advancement of China and North Korea, and so forth.41 It is from here that another serious problem for this concept emerges. On the one hand, the balancing strategy indeed presupposes Russias association with anti-Western identities shaped by the postcolonial type of discourse that emanates from peripheral or semiperipheral actors. On the other hand, in addressing the most pressing security issues, Russia tends to appeal toand prefers to deal withthe transatlantic community. These two dispositions may not sit easily together. It seems that all of these concerns are now seriously taken into account by the policymakers in Moscow, which has finally made them tone down the balance-of-power rhetoric. The resulting trend points in the direction of a compromise vision of multipolarity that is captured by the concept of great-power management.

Great-power (Mis)Management: An Old/New Pragmatism?

Great-power management was originally understood by Bull as one of the key institutions of international society that functions as a mechanism for coordinating policy strategies of key powerholders that prioritizes order over justice.42 In fact, what Bull advocated as GPM was a form of security provision tuned to police-type activities and, thus, politically sterile. Yet GPM, or a concert of great powers43 (also dubbed by some authors great power multilateralism44), may have different meanings in the Russian discourse. One meaning is of the geopolitical background: it affirms the utility of various axes that ought to link Russia to the strongest international actors, including the United States, Germany, or Japan. In its most radical versionadduced, in particular, by Alexander Duginthe Russian government is urged to make restitution of Kaliningrad and the Kuril Islands in return for privileged relations with Germany and Japan.45 Anotherand much more widespreadapproach to GPM denotes a pragmatically depoliticized type of bargaining between the world poles. Perhaps, a NATO-Russia Council as well as club-like international entities (G7 and G8) could exemplify this model of multipolarity. Arguably, the Georgia war, despite the seemingly deep cleavages between Russia and major Western governments that it provoked, eventually fostered some elements of GPM. The relations between Russia and NATO, which reached their peak of securitization in August 2008, have gradually evolved into a more business-as-usual type of bargaining with concessions from both sides. Under the Obama administration, the United States cancelled the deployment of antimissile systems in Poland and the Czech Republic, and decreased its involvement in countries that Russia includes in its sphere of interest. Relations between the EU and Russia gained new momentum as a result of the talks between Medvedev and Sarkozy. NATO has frozen the accession process for Georgia and Ukraine, and Russia has increased its involvement in the operation in

Andrey Makarychev & Viatcheslav Morozov

365

Afghanistan and pledged to cooperate against the Somali pirates. All of these developments seem to corroborate Alexander Astrovs prediction that GPM tends to evolve into a police-type administration of the most disastrous conflicts in the world.46 As argued by some authors, the EU-Russia partnership could be seen as an instrument to prevent Russia from pursuing a strategy of balancing the West through aligning with non-Western governments.47 Thus, the Institute for Contemporary Development (INSOR), an influential Moscow-based think-tank, argues that the EU growth seems to be quite in line with the idea of multipolarity and calls for strategic partnership with EU in such spheres as the formation of common energy space and joint markets for transportation and technology transfer.48 Similarly, Medvedevs new security architecture proposals are being introduced and discussed mainly between Russia, on the one hand, and the EU and NATO, on the other. It seems that the resulting trend of Russias attempts to reconcile the need to keep reasonably good relations with the West and the politically significant inertia of the balance-of-power approach points toward an ever greater significance of GPM for the future foreign policy agenda. There are, however, two key questions looming large at this juncture. First, what are the powers implied by the great-power concept? This question seems to be underproblematized by Bull who was certain that powers are states; but more contemporaryand, arguably, more dynamicreading of the English school might give a more complex picture. Power is certainly state based, yet powers are no longer limited by the states alone. In fact, powers are increasingly becoming structural phenomena, incorporating international or supranational organization(s) like NATO or the EUand often nonstate actors as well. This is not a purely theoretical matter: for Russia, this complex composition of the dominating Western powers definitely causes a large problem. The Kremlin feels disoriented and disadvantaged in situations where its major international partners do not act on an individual basis supposedly predetermined by national interests, as Russia itself prefers to do, but in a more institutional fashion. Second, there is the question of correlation and contradiction between the explicitly political traits of the GPM model, on the one hand, and its depoliticizedmanagerial, in the strict sensepotential, on the other hand. As the experience of the past two decades has demonstrated, the questions of law and order are even more politicized on the international arena than in most domestic settings. The legitimacy derived from the idea of a concert of powers is problematic at best while an order based on coercion, even if there are enough resources for that, cannot be stable because in some parts of the world it will inevitably be perceived as oppressive and promote guerilla warfare, terrorism, and other forms of resistance. A return to the more traditional and egalitarian multilateralist agenda therefore can still be in the cards in a more long-term perspective.

366

Multilateralism, Multipolarity, and Beyond

Beyond the Self-interest State-centrism

All in all, the state-plus, interest-based approaches to multipolarity listed in Table 1 have relatively less significance for the understanding of Russias take on multilateralism. However, they still need to be discussed, even if briefly, because a complete absence of an academically conceivable strategy from the policy agenda is always symptomatic as to the basic premises on which this policy agenda is built. This is the case, in particular, with polycentrism, which has been a topic of a rather lively debate in the academic literature and even has made it to certain policy contexts. Polycentrism describes situations of multilayered and diffuse governance and, thus, emphasizes its distinctive feature of emanating from multiple locales at the same time. The dispersal of power not only has occurred across different layers and scales of international relations from the local to the global, but also with the emergence of various regulatory mechanisms in the private sector alongside those in the public sector. Polycentric in this context is synonymous with a globalization-friendly world; transnational and cross-boundary relations; and nonterritorial and spatial flows. A polycentric world embraces such global changes as prevalence of mobile or ad hoc coalitions, growing asymmetry and turbulence, the multiplicity of political and institutional playgrounds for international subjects, and an open (i.e., inclusive and nondiscriminatory) model of regionalism grounded in a network of centers of growth and leaving much space for the participation of nonstate actors.49 Yet this reading of polycentrism is conspicuously absent from the Russian official foreign policy discourse. For many Russian officials, including Foreign Minister Lavrov, polycentrism is synonymous to multipolarity. This interpretation misses a meaningful point: the idea of polycentrism is grounded in a particular domain of theory located at the intersection of transnationalism and a group of postsovereignty/postnational conceptualizations. In a polycentric world, the state is not in a position to preserve its modern or Westphalian characteristics; it has to undergo deep domestic transformations in reaction to the growingperhaps enforcedcompetition with other actors, sometimes more resourceful and normatively appealing than the states. It seems, however, that this worldview is completely alien to the contemporary Russian elites, who continue to focus on the idea of a strong paternalistic state which, at the least, guarantees order and stability and, at best, promotes state-driven modernization.50 The idea of multiregionalism apparently has more resonance with the policymakers in Moscow. It rests on the plurality of regional orders, or a system of international order built around regional spheres of responsibility. This is where the idea promoted by the English school concerning regional states-systems or regional international societies or many worlds of different regionalism originates.51 As Barry Buzan and Ole Wver describe it,

Andrey Makarychev & Viatcheslav Morozov

367

multiregionalism may be best realizable in the absence of superpowers, which by definition largely transcend the logic of geography and adjacency in their security relationships.52 This conception seems, by and large, to correspond to Russias vision of international society. It is symptomatic that multipolarity discourse in Russia includes explicit references to the idea of regionalization of global politics.53 Regionalization has two meanings within this context. According to Lavrov, it denotes, on the one hand, a search for regional solutions for conflicts and crises which, more specifically, means the need to avert possible interventions on the part of external powers, among which NATO in general and the United States in particular seem to be perceived by the Kremlin as the most menacing. On the other hand, regionalization could serve as an insurance mechanism to prevent potential fragmentation of international society as a result of what might be dubbed de-globalization, or a reversal of the global moment.54 The most paradoxical characteristic of the concept of multiregionalism in both readingsas a possibility for local crisis management and as an insurance against a Hobbesian worldis its ambiguity. Being one of the possible interpretations of multipolarity, it by the same token questions Russias exclusive sphere of influence in its near abroad. Instead of substantiating a Kremlin-protected area of vital interest that serves as one proof of Russias claims for the status of a major international pole, the multiregionalism perspective disassembles the post-Soviet space into several regions that do not necessarily remain under Russias supervision. In particular, the Western CIS and even the South Caucasus can in this perspective become legitimate objects for EU enlargement and neighborhood policies. The EU strategically invests its resources and efforts in region building for both pluralizing Europes regional scene and making it more adaptable and sensitive to Europeanization. The United States is supportive of this approach, although in recent years it has placed more emphasis on the regions further east. For Russia, playing along means that it would adopt a multilateral perspective much in the spirit of Medvedevs proposal for a new European security architecture. However, the initial design of the European neighborhood policy put Russia in the position of a policy recipient rather than policymaker, which was definitely unacceptable to the Kremlin and provoked a rather hostile response. It seems that by now the chance of finding a multilateral regionalist solution for the European neighborhood has been lost. Some Russian scholars argue that multipolarity can be successful only when conceptualized as the dialogue of civilizations,55 thus reading global diversity in cultural, sometimes quite essentialist, terms. Most often, the civilizational approach insists on Russias standing as one of the worlds civilizations, possessing its own distinctive cultural profile in the world. Besides, Russia often claims to possess an almost unique capability of bridging gaps between civilizations, to promote intercivilizational dialogue and a partnership

368

Multilateralism, Multipolarity, and Beyond

of civilizations. It is even claimed that Russia consistently pursues this policy in the United Nations, UNESCO, OSCE and the Council of Europe, as well as other international and regional organizations, including in the context of cooperation with the Organization of the Islamic Conference [OIC].56 Russias obtainment of observer status in the OIC in 2005 is probably the only unambiguous example of joining a multilateral institution on the basis of civilizational approach. It was motivated by the Kremlins attempts to redefine Russias identity as a country of autochthonous Islam, which was part of a broader attempt to defend the values of civic patriotism against the background of the war on terror.57 Yet at a closer look, this hypothetical brokerage appears to be a sort of wishful thinking aimed basically for domestic consumption since it fails to explain why the West and the East would not be able to get along without the Russian mediation. Moreover, the notion of civilizational diversity, if it is to have any meaning distinct from the simple idea of pluralism, must presuppose certain irreducible cultural differences that prevent civilizations from complete mutual transparency.58 It is difficult to see the added value of this approach if it is to be consistently pursued in various multilateral institutions as mentioned aboveif anything, it can hamper, rather than be conducive to, genuine multilateralism. In effect, the main significance of civilizational diversity for practical foreign policy is the fact that it is used as a tool of cultural protectionism59 directed against democracy promotion by the West.60 The civilizational approach, however, is not the only one providing normative arguments against Western democratic activism. Paradoxically, democracy promotion can also be contained by the references to international democracy. The Russian standpoint suggests that it is multipolarity that fosters the development of democratic institutions in the international arena, not vice versa. In other words, the key argument is that all types of multipolarity are equivalent to democracy as seen from the international society perspective. Exploring the democratic potential of multipolarity, Russian leaders are sometimes inclined to project the language traditionally suited for domestic purposes into the domain of international politics. In his Munich speech mentioned earlier, President Putin lambasted the US worldview as presumed upon one single center of power and one single master, one sovereign, a situation that has nothing to do with democracy.61 Foreign Minister Lavrov went as far as to call Russia a territory of freedom in international society due to its resolution to openly raise a set of issues that were either ignored or silenced earlier.62 This reading of multipolarity definitely favors multilateral frameworks, so long as the latter are not dominated by the West. It has motivated Russia to actively take part in a number of new international projects, the most important being perhaps the Group of 20 (G-20) and Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS). The latter, in particular, has grown from a simple de-

Andrey Makarychev & Viatcheslav Morozov

369

scriptive acronym coined by a Goldman Sachs analyst to an institutionalized international arrangement with regular summit meetings. It looks quite probable that cooperation among the countries with a strong disposition toward postcolonial ideologies has been the key reason why the Russian leaders have started to play with anticolonial rhetoric.63 However, there are also serious problems with this approach at the conceptual as well as at the practical level. In its promotion of international democracy, Moscow does not actually differentiate between partnerships with countries like Brazil and India, on the one hand, and China, Iran, and Venezuela, on the other hand. In the Kremlins worldview, international democracy is void of political meaning and reduced to the mere multiplicity of sovereign states, regardless of the nature of their political regimes. Multipolarity, understood as a simple redistribution of the alleged world power among several poles of force, makes the issues of liberty, free competition, and other core elements of democracy either irrelevant or equally acceptable along with authoritarianism, totalitarianism, the nonmarket economy, and so forth.64 Besides, it seems that the superficial similarity of political rhetoric between Russia and, for instance, some Latin American countries, actually conceals a fundamental divergence in the understanding of such key concepts as people or social justice.65 All in all, given the unscrupulousness of the choice of partners in Russias promotion of international democracy, it becomes difficult to differentiate between this model and the traditional balance of power ideology.

Conclusion There is no doubt that multilateralism has a normative appeal in the eyes of Russian policymakers, as they often criticize the West and justify their own policies by referring to the need to avoid unilateral action. At the same time, the meaning of multilateralism in the Russian context is seldom straightforward. It is fundamentally conditioned by the notion of multipolarity, which plays a key role as the ideological background of foreign policy thinking and practice. Since the discourse of multipolarity also presents a complex matrix of diverging attitudes, many of which point in the direction of multilateral solutions, we can speak about a whole range of multilateral frameworks that Russia either tries to create or takes part in. The key difference between these frameworks is defined not in terms of how they are structured or who their (prospective) members are, but rather from the point of view of their ideological significance. Thus, the multilateralism promoted by the EU and the United States presupposes that Russia joins the established international institutions whose agenda is set mostly by the West. However, these approaches are criticized by Russia as, in fact, being a form of collective unilateralism, and this critical attitude gives rise to a number of alternative visions of a multipolar world. It appears that at least two of thembalance of power and the promo-

370

Multilateralism, Multipolarity, and Beyond

tion of international democracylead to a practical search for multilateral solutions that could provide an alternative to transatlantic multilateralism. However, Russias concern with international democracy is obviously instrumental and driven by the desire to counterbalance the West, so at least for the time being this cannot be described as a viable vision of the future world order. The balance of power, on the other hand, looks conspicuously old fashioned and counterproductive in view of Russias increasingly pressing security concerns, especially in Asia. The trend that results from all these contradictory developments is the increasing prominence of GPM as a form of multipolarity that apparently allows Russia to reconcile its unwillingness to join the transatlantic institutions as a junior partner and the practical need to cooperate with the EU, NATO, and the United States. As a form of international order, GPM is probably further away from multilateralism than any other model of multipolarity, at least if multilateralism is understood as being premised on the fundamental equality of all participants of the international system. GPM, on the contrary, favors a special status for the great powers as a flip side of greater responsibility for international stability and security. In this respect, the new pragmatism of many political leaders in the West resonates with the Russian self-perception as a great power that is entitled to a special status already by virtue of its size and geopolitical position. At the same time, a world order based on a concert of powers leaves much to be desired in terms of legitimacy, and thus might prove to be unsustainable in the longer run.

Notes

Andrey Makarychev is professor and research fellow at the Institute for East European Studies, Free University of Berlin. He has lectured at the Universities of Malm (Sweden), Odessa (Ukraine), and Baku (Azerbaijan), among others. He has done work for Nizhny Novgorod Linguistic University, Danish Institute of International Relations, and the Center for Conflict Studies at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH Zurich). He has participated in several research projects with the Center for European Policy Studies (Brussels), CIDO (Barcelona), and London School of Economics. Viatcheslav Morozov is currently professor of EU-Russia Studies and chairman of the executive board of the Centre for EU-Russia Studies, University of Tartu, Estonia. Until January 2010, he was associate professor at the School of International Relations and director of the International Relations and Political Science Program at the Smolny College of Liberal Arts and Sciences (both at St. Petersburg State University, Russia). He has published extensively on Russian national identity and foreign policy, in particular on Russias role in Europe and relations with the European Union. Most recently, his work has focused on the Russian interpretation of democracy and sovereignty in the context of poststructuralist and postcolonial social theory. The work on this article has been supported by the Estonian Science Foundation (grant ETF8295). 1. Viatcheslav Morozov, Resisting Entropy, Discarding Human Rights: Romantic Realism and Securitization of Identity in Russia, Cooperation and Conflict 37 (2002): 409430.

Andrey Makarychev & Viatcheslav Morozov

371

2. Alexei Bogaturov, Sindrom pogloscheniya v mirovoy politike, Pro et Contra 4 (1999): 28. 3. Viatcheslav Morozov, Sovereignty and Democracy in Contemporary Russia: A Modern Subject Faces the Post-Modern World, Journal of International Relations and Development 11 (2008): 152180. 4. Bogaturov, Sindrom pogloscheniya v mirovoy politike, p. 40. 5. See Robert Legvold, The Role of Multilateralism in Russian Foreign Policy, in Elana Wilson Rowe and Stina Torjesen, eds., The Multilateral Dimension in Russian Foreign Policy (London: Routledge, 2009), pp. 2145. 6. See, for example, Elana Wilson Rowe and Stina Torjesen, Key Features of Russian Multilateralism, in Rowe and Torjesen, The Multilateral Dimension in Russian Foreign Policy, pp. 121241. 7. The Foreign Policy Concept of the Russian Federation, approved by the president of the Russian Federation, Vladimir Putin, 28 June 2000, www.fas.org/nuke /guide/russia/doctrine/econcept.htm. 8. Vladimir Putin, Speech and the Following Discussion at the Munich Conference on Security Policy, 10 February 2007, http://archive.kremlin.ru/eng/speeches /2007/02/10/0138_type82912type82914type82917type84779_118123.shtml. 9. Dmitry Medvedev, speech presented at the World Policy Conference, Evian, France, 8 October 2008, www.kremlin.ru/text/apears/2008/10/207422.shtml. 10. Fred Halliday, International Relations in a Post-Hegemonic Age, International Affairs 85 (2009): 39. 11. The Foreign Policy Concept of the Russian Federation, approved by the president of the Russian Federation, 12 July 2008, http://www.un.int/russia/new/Main Root/koncept.html. 12. Sergei Lavrov, statement at the UN General Assembly, 27 September 2008, www.un.org/en/ga/63/generaldebate/russia.shtml. 13. Sergei Lavrov, O Programme effektivnogo ispolzovania na sistemnoi osnove vneshnepoliticheskikh faktorov v tseliakh dolgosrochnogo razvitia Rossiiskoi Federatsii, http://www.scribd.com/doc/31280149/. This document was leaked to the Russky Newsweek magazine, but has never been officially published. For details, see Russky Newsweek, 11 May 2010, pp. 1219. 14. Morozov, Sovereignty and Democracy, pp. 154, 167172. 15. The Foreign Policy Concept of the Russian Federation, 2008. 16. For a thorough elaboration of this point, see Morozov, Sovereignty and Democracy. 17. Nathalie Tocci, Profiling Normative Foreign Policy: The European Union and Its Global Partners, in Nathalie Tocci, ed., Who Is a Normative Foreign Policy Actor? (Brussels: Center for European Policy Studies, 2008), p. 7. 18. Hedley Bull, The Anarchical Society: A Study of Order in World Politics, 3rd ed. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002). 19. Grant Charles and Tomas Valasek, Preparing for the Multipolar World: European Foreign and Security Policy in 2020, EU 2020 Essay (London: Center for European Reform, December 2007). 20. Wolfgang Zellner, Russia and the OSCE: From High Hopes to Disillusionment, Cambridge Review of International Affairs 18 (2005): 389402. 21. Timothy J. Colton, Post-Postcommunist Russia, the International Environment and NATO, in Aurel Braun, ed., NATO-Russia Relations in the Twenty-First Century (London: Routledge, 2008), pp. 2538. 22. Alexander A. Pikayev, Russias Attitude Towards Nuclear Non-Proliferation Regimes and Institutions: An Example of Multilateralism? in Rowe and Torjesen, The Multilateral Dimension in Russian Foreign Policy, pp. 6982.

372

Multilateralism, Multipolarity, and Beyond

23. Jakub M. Godzimirski, Russia and the OSCE: From High Expectations to Denial? in Rowe and Torjesen, The Multilateral Dimension in Russian Foreign Policy, pp. 121141. 24. Pavel K. Baev, Leading in the Concert of Great Powers: Lessons from Russias G8 Chairmanship, in Rowe and Torjesen, The Multilateral Dimension in Russian Foreign Policy, pp. 5868. 25. Andres slund, Why Doesnt Russia Join the WTO? Washington Quarterly 33 (2010): 4963. 26. Dmitry Medvedev, Speech at Meeting with German Political, Parliamentary and Civic Leaders, Berlin, 5 June 2008, http://archive.kremlin.ru/eng/speeches /2008/06/05/2203_type82912type82914type84779_202153.shtml. 27. European Security Treaty, draft, 29 November 2009, published on the official website of the president of Russia: http://eng.news.kremlin.ru/news/275. 28. Helsinki Plus: Towards a Human Security Architecture for Europe, First Report of the EU-Russia Human Security Study Group (London: London School of Economics: May 2010). 29. Ekonomicheskie interesy i zadachi Rossii v SNG (Moscow: INSOR, 2010), p. 84. 30. Ivan Krastev and Mark Leonard, The Spectre of a Multipolar Europe (London: European Council on Foreign Relations, 2010). 31. Derek Averre, From Pristina to Tskhinvali: The Legacy of Operation Allied Force in Russias Relations with the West, International Affairs 85 (2009): 575591. 32. Jason Motlagh, With US Approval, Moscow Heads Back to Afghanistan, Time, 24 August 2010, www.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,2012440,00.html. 33. Alexandr Filippov, Universum ili pluriversum? Kosmopolis, no. 3 (2004): 90. 34. Yuriy Fiodorov, Kriticheskiy vyzov dlia Rossii, Pro et Contra 4 (1999): 19. 35. Dmitry Medvedev, interviewed by the BBC, Sochi, Russia, 26 August 2008, www.kremlin.ru/text/appears/2008/08/205775.shtml. 36. Rossiiskiy konservatizmideologia partii Edinaya Rossiya (Moscow: Center for Social Conservative Policy, 2009), p. 36. 37. Stephen Aris, Russias Approach to Multilateral Cooperation in the PostSoviet Space: CSTO, EurAsEC and SCO, Russian Analytical Digest 76 (2010): 24. 38. Pavel K. Baev, Medvedev Enjoys Foreign Policy Successes, Eurasia Daily Monitor, 13 December 2010, www.jamestown.org/programs/edm/single/?tx_ttnews [tt_news]=37271&cHash=c60e9b27c6. 39. For an assessment of these and similar claims, see Alexander Astrov, Great Power Management Without Great Powers? The Russian-Georgian War of 2008 and Global Police/Political Order, in Alexander Astrov, ed., The Great Power (Mis)Management: The Russian-Georgian War and Its Implications for Global Political Order (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2011), pp. 123. 40. Vadim Tsymbursky, Geopolitika dlia evraziiskoi Atlantidy, Pro et Contra 4 (1999): 151. 41. Vladimir Kulagin, Globalnaya ili mirovaya bezopasnost, International Trends 5, no. 2 (2007): 50. 42. Bull, The Anarchical Society, p. 178. 43. Rossiiskiy konservatizmideologia partii Edinaya Rossiya, p. 37. 44. Rowe and Torjesen, The Multilateral Dimension in Russian Foreign Policy, p. 2. 45. Alexander Dugins interview with Russia.ru web portal, 28.05.2009, www.russia.ru/video/duginkurili. 46. Astrov, Great Power Management Without Great Powers? 47. Jordi Vaquer i Fanes, Focusing Back Again on European Security: The Medvedev Proposal as an Opportunity (Barcelona: CIDOB, 2010). 48. Igor Yurgens, ed., RossiyaEvropeiskiy Souyz: k novomu kachestvu otnosheniy (Moscow: Ecoinform, 2008), p. 26.

Andrey Makarychev & Viatcheslav Morozov

373

49. See Jan Scholte, Globalization and Governance: From Statism to Polycentrism, CSGR Working Paper No. 130/04 (Warwick: University of Warwick, Center for Study of Globalisation and Regionalisation, 2004); Murat Gul, The Concept of Change and James N. Rosenau: Still International Relations? African Journal of Political Science and International Relations 3 (2009): 199207, www.academic journals.org/ajpsir/contents/2009cont/May.htm. 50. For further development of this point, see Viatcheslav Morozov, Modernizing Sovereign Democracy? Russian Political Thinking and the Future of the Reset, PONARS-Eurasia Policy Memo No. 130 (2010), www.gwu.edu/~ieresgwu/assets /docs/pepm_130.pdf; Viatcheslav Morozov, Dmitry Medvedevs Conservative Modernization: Reflections on the Yaroslavl Speech, PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 134 (2010), www.gwu.edu/~ieresgwu/assets/docs/pepm_134.pdf. 51. Andrew Hurrell, One World? Many Worlds? The Place of Regions in the Study of International Society, International Affairs 83 (2007): 128. 52. Barry Buzan and Ole Wver, Regions and Powers: The Structure of International Security (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), p. 46. 53. Sergei Lavrov, Mezhdunarodnie otnoshenia v novoi systeme koordinat, Rossiyskaya gazeta, 8 October 2009, p. 3. 54. Ibid. 55. Boris Martynov, Mnogopoliarniy ili mnogotsivilizatsionniy mir? International Trends 7 (2009): 64. 56. The Foreign Policy Concept of the Russian Federation, 2008. Generally speaking, the document is full of references to the civilizational approach. 57. See, for example, Vladimir Putin, interviewed by Aljazeera, Moscow, 10 February 2007, www.kremlin.ru/appears/2007/02/10/2042_type63379_118108.shtml. 58. This was the essence of the original Huntingtonian argument. See Samuel Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations? Foreign Affairs 72 (1993): 2249. 59. Valerii P. Goregliad, Rossiyarimskaya provintsiya? Nezavisimaya gazeta, 19 March 2002, p. 5. 60. Morozov, Resisting Entropy. 61. Putin, Vystuplenie na Miunkhenskoi konferentsii. 62. Sergei Lavrov, The Present and the Future of Global Politics, Russia in Global Affairs 5 (2007): 1213. 63. Viatcheslav Morozov, Russias Counter-Hegemonic Strategies: Discovering a Postcolonial Identity, in Cristina Pecequilo, ed., A Rsia: Desafios Presentes e Futuros (Curitiba, Brazil: Juru, 2010), pp. 191193. 64. Yuri Fiodorov, Kriticheskiy vyzov dlia Rossii, p. 21. 65. Elena Pavlova, Latinoamrica y Rusia: Una aproximacin ilusoria, Foreign Affairs Latinoamrica 11 (2011): 5867.

Copyright of Global Governance is the property of Lynne Rienner Publishers and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Bechev - The Politics in The Regional Identity in The BalkansDokument23 SeitenBechev - The Politics in The Regional Identity in The Balkanser_dalmataNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- AlbaniaDokument22 SeitenAlbaniaАлександр БовдуновNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Voskressenski 2006Dokument39 SeitenVoskressenski 2006Александр БовдуновNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Asymmetry Theory and China's Concept of Multipolarity - Brantly WomackDokument17 SeitenAsymmetry Theory and China's Concept of Multipolarity - Brantly WomackАлександр БовдуновNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Oc-427 20101102 103808Dokument14 SeitenOc-427 20101102 103808Александр БовдуновNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Basic Concepts of Law PDFDokument1 SeiteBasic Concepts of Law PDFRobert RoblesNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Glossary of Diplomatic TermsDokument13 SeitenGlossary of Diplomatic TermsAlina100% (6)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Asdfsad Sdfadsa AsfdadasDokument2 SeitenAsdfsad Sdfadsa Asfdadascpscbd9Noch keine Bewertungen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Syllabus For: Evening Masters in International Relations (EMIR) Program Department of International RelationsDokument11 SeitenSyllabus For: Evening Masters in International Relations (EMIR) Program Department of International RelationsFerdous HasanNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- PCA Rules CommentaryDokument171 SeitenPCA Rules Commentarybeejal ahujaNoch keine Bewertungen

- N 1726996Dokument31 SeitenN 1726996Yasser SobhyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Position Paper - Anish GauravDokument2 SeitenPosition Paper - Anish GauravGreatAkbar10% (1)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- World War 1 & 2 RelationDokument4 SeitenWorld War 1 & 2 RelationDistro MusicNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- How To Get Orders On Snapdeal.Dokument2 SeitenHow To Get Orders On Snapdeal.amershareef337100% (1)

- PIL DigestsDokument46 SeitenPIL Digestslourdesctaala75% (4)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Chandler - Peacebuilding - The Twenty Years' Crisis, 1997-2017 (2017, Palgrave Macmillan)Dokument242 SeitenChandler - Peacebuilding - The Twenty Years' Crisis, 1997-2017 (2017, Palgrave Macmillan)Maria Paula Suarez100% (1)

- AtsisiųstiDokument317 SeitenAtsisiųstiDominykasAurilaNoch keine Bewertungen

- "Occupy Imperialism" Solidarity Statement From Marcos Garcia, Labor Attache of Venezuelan Embassy - Uhuru Solidarity MovementDokument5 Seiten"Occupy Imperialism" Solidarity Statement From Marcos Garcia, Labor Attache of Venezuelan Embassy - Uhuru Solidarity MovementAri El VoyagerNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Notting Hill Carnival - Belfast StyleDokument2 SeitenNotting Hill Carnival - Belfast StyleNevinNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Pil Cases 1591317Dokument7 SeitenPil Cases 1591317Reino CabitacNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journal of International Commerce and Economics - by UsitcDokument47 SeitenJournal of International Commerce and Economics - by Usitcratna ayuNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Lessons From Cambodia's Entry Into The World Trade OrganizationDokument185 SeitenLessons From Cambodia's Entry Into The World Trade OrganizationWen-Hsuan HsiaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pierre Goldschmidt CritiqueDokument281 SeitenPierre Goldschmidt Critiquedave742Noch keine Bewertungen

- What To Do About North Korean Nuclear Weapons: Allied Solidarity, The Limits of Diplomacy, and The "Pain Box"Dokument20 SeitenWhat To Do About North Korean Nuclear Weapons: Allied Solidarity, The Limits of Diplomacy, and The "Pain Box"Hoover InstitutionNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Three Territorial DomainsDokument2 SeitenThe Three Territorial DomainsJapheth Gofredo80% (5)

- Us-China Relations and The South China Sea ConflictDokument15 SeitenUs-China Relations and The South China Sea ConflictAmeer HamzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Superpower Geography Revision GuideDokument7 SeitenSuperpower Geography Revision Guidepenji_manNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Concert of Medium Powers Its Origi Composition and ObjectivesDokument8 SeitenThe Concert of Medium Powers Its Origi Composition and ObjectivesAlexander DeckerNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- World War 1 NotesDokument3 SeitenWorld War 1 NotessugarbabegigglesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Goldstein 10E PPT CH04 LectureDokument36 SeitenGoldstein 10E PPT CH04 LectureKalsoom AkhtarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theory of Realism in International Relation BS Lecture 3.Dokument17 SeitenTheory of Realism in International Relation BS Lecture 3.Shuja ChaudhryNoch keine Bewertungen

- List of Embassies in DelhiDokument87 SeitenList of Embassies in DelhiSanjiv ErryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diplomacy Handout PDFDokument15 SeitenDiplomacy Handout PDFSatyam PathakNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pentagon Papers Part V B 4 Book IDokument456 SeitenPentagon Papers Part V B 4 Book IAaron MonkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Russian Revolution QuestionsDokument3 SeitenRussian Revolution Questionsapi-293588788Noch keine Bewertungen

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)